HAL Id: hal-02544615

https://inria.hal.science/hal-02544615

Submitted on 16 Apr 2020

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-

entic research documents, whether they are pub-

lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diusion de documents

scientiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in News

Consumption

Yuval Cohen, Marios Constantinides, Paul Marshall

To cite this version:

Yuval Cohen, Marios Constantinides, Paul Marshall. Places for News: A Situated Study of Context

in News Consumption. 17th IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (INTERACT), Sep

2019, Paphos, Cyprus. pp.69-91, �10.1007/978-3-030-29384-0_5�. �hal-02544615�

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in

News Consumption

Yuval Cohen

1

, Marios Constantinides

2

, and Paul Marshall

3

1

2

3

Abstract. This paper presents a qualitative study of contextual fac-

tors that affect news consumption on mobile devices. Participants re-

ported their daily news consumption activities over a period of two weeks

through a snippet-based diary and experience sampling study, followed

by semi-structured exit interviews. Wunderlist, a commercially available

task management application and note-taking software, was appropri-

ated for data collection. Findings highlighted a range of contextual fac-

tors that are not accounted for in current ‘contextually-aware’ news de-

livery technologies, and could be developed to better adapt such tech-

nologies in the future. These contextual factors were segmented to four

areas: triggers, positive/conducive factors, negative/distracting factors

and barriers to use.

Keywords: News Consumption · Mobile · Snippet technique · Context

Awareness · Contextual Factors

1 Introduction

News consumption is changing rapidly thanks to digital methods of consump-

tion, reinforced by almost ubiquitous handheld mobile devices. Social networking

platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and even direct messaging platforms such as

WhatsApp and Snapchat are becoming de facto distribution channels for news

stories. This wrests control over how news is presented to and consumed by

users away from publishers [40]. Furthermore, news content is increasingly being

presented in a ‘contextually-aware’ fashion, according to topics and locations.

While there has been a significant concern about and analysis of how emerg-

ing news consumption patterns can lead to the formation of ‘filter bubbles’ [41,

45], and how fake news stories spread through social networks [33], there has been

little focus on understanding exactly how social and personal context affect news

consumption habits (cf. [22]). The study presented in this paper first aims to

identify contextual factors relevant to news consumption, especially those of a

more qualitative and experiential nature, which have typically been overlooked

in previous research. Such research often defines context quite broadly [1] but

tends to focus on objective quantifiable aspects of context, such as geographical

location [19]. Our aim is to focus on what contextual factors are important prior

2 Y. Cohen et al.

to trying to use sensor data to identify them. Arguably, prior work has tended to

focus on those contextual factors that are straightforward to measure rather than

most salient from the users’ perspective. Furthermore, the study aims to explore

the effects of any identified contextual factors on user behaviour related to news

consumption, and the influence it has on the news consumption experience.

Our findings highlight a range of social, cultural, affective and individual

factors that drive the manner in which users consume news. We discuss these in

relationship to opportunities for the development of new types of context-aware

and adaptive news applications.

2 Background

2.1 Mobility and Context in HCI

The shift towards consumption on mobile devices is not an isolated phenomenon

within news consumption, and can be categorised as part of a larger trend de-

scribed by social scientists as a ‘mobility turn’ [56]. This perspective recognizes

that human interaction with technologies is increasingly distributed over both

time and space, and occurs in disparate social and physical contexts. Dourish &

Bell [23] focus on mobility in the context of urbanism, and treat it as a spatial

construct in which individuals render a space meaningful by acting in a certain

way. Some approaches in social sciences describe a set of codes that govern in-

teractions or non-interactions between individuals in public spaces [25]. Other

perspectives, more relevant to the current study, have focused on the role of tech-

nologies in the isolation of individuals from their environment, creating “solitude

and similitude” [3, 26].

An additional area of mobility research is studies of mobile work. While news

reading can generally be considered a non-work task, studies of mobile work have

the potential for generalizable insights. For example, Perry et al. [46] note the

existence of ‘dead times’–periods of time which workers spend riding various

forms of transportation or waiting for them to arrive, which creates opportunity

for news reading on mobile devices [20]. Other studies have focused on issues such

as battery life, connectivity and device limitations–all issues with relevance to

everyday mobile information needs [10]. User experience of news applications has

also been studied, particularly within the young generations, revealing factors

such as quick understanding, consistency, fun, diversity, and interests [57].

A large body of research in relation has focused on context in the develop-

ment of recommender systems. A comprehensive review of the state-of-the-art

news recommendation systems can be retrieved from [30]. In addition to partic-

ular challenges of news recommendations (e.g., recency aspects), the advanced

capabilities of today’s smartphones open a new road to enhance and transform

news consumption to a more personalized experience. The continuous connec-

tivity and access to smartphones’ sensors enable aspects of user’s context to

be incorporated into interaction with mobile apps. For example, Appazaar pro-

posed by Bohmer et al. [38], generates app recommendations combining the ac-

tual app usage and user’s current context. Similarly, Tavakolifard [54] leveraged

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in News Consumption 3

users’ location information to provide tailored news recommendation. Pessemier

et al. [17] demonstrated the potential of a context-aware content-based recom-

mendation engine which induces higher user satisfaction in the long run, and at

the same time enables the recommender to overcome the cold-start problem and

distinguish user preferences in various contextual situations.

Context in relation to news consumption has also been studied by analyz-

ing social media behaviour. Social networking platforms such as Facebook and

Twitter are becoming de facto distribution channels of news. Many apps lever-

age knowledge from users’ social activities to recommend and deliver targeted

news feed. Pulse, for example, developed by LinkedIn, is an example of one

such app that delivers personalised news from a user’s professional network. Lu-

miNews [31], another example, leverages users’ location, social feed, and their

in-app actions to automatically infer their news interests. These, both implicit

and explicit, signals were found to improve recommendations and improve user’s

satisfaction over time.

2.2 News Consumption and Adaptive News Interfaces

Data from Reuters [40] shows that the use of smartphones to view news media

is rapidly growing, and is seen as the future for the news industry, especially

with younger demographics [44] – a transformative change from times when

mobile devices were thought of as “supplementary” to news-reading [58]. The

Reuters report discusses ‘gateways’ through which news is discovered, such as

search, social networks, and news-reading apps. It distinguishes between the

different roles that Facebook and Twitter play in news consumption – initiated

consumption vs. casual or play a central role in the discovery and presentation

of content. However, while these platforms increasingly direct people to online

news content (and play a role in the spreading of ‘fake news’ (e.g., [33]), we still

know little about the contextual factors that lead people to choose to consume

that content in particular situations.

Previous work relating to contextually-aware news consumption technology

has focused on appropriation of features and sensing technology within existing

technological platforms. One of the uses for such appropriated data is the devel-

opment of adaptive interfaces systems that ‘learn’ user habits and use patterns,

and adapt a user interface to better match those patterns [28]. Constantinides

et al. [14, 15] developed ‘Habito News’, an Android news app that presented

participants with live news items while simultaneously logging frequency, time

spent and location of reading, as well as speed and article completion rate using

scroll-tracking. The goal of this research was to profile and classify reading habits

into typical patterns of use, and to use those classifications as background to the

development of adaptive, context-dependent news-reading interfaces to match

them. Other notable work in this area [4, 54] has focused on customization of

content, rather than adaptation of the interface through which it is presented.

The current study aims to understand the contextual factors relating to news

consumption in order to understand if they might be classifiable in a way that

could drive the adaptation of content or the interface on which it is read.

4 Y. Cohen et al.

3 Method

In recent years, HCI researchers have used a variety of in-situ methods that were

previously limited to psychology and social sciences to better understand user

behaviour in general and context of use in particular. Some methods, such as

ethnography, typically require a researcher to be present among participants in

order to collect data [55], while others such as diary studies and experience sam-

pling rely on self-reporting by participants. Diaries have been used in studies of

information needs, with computerized [2, 9, 11, 32] and non-computerized [12, 18,

43] apparatus. The experience sampling method (ESM) has been used to obtain

in-situ information that is more real-time [9, 10, 13], and can be supplemented

by interviews aided by memory cues based on participant responses [7, 8, 36, 39].

A particular focus of self-reporting studies has been to lower the data entry

and overall participation burden inherent in such studies, especially when entries

are done under mobile conditions. Brandt et al. [6] proposed a ‘snippet’ technique

in which participants chose an input modality that they were most comfortable

with, and captured small pieces (‘snippets’) of information about their experience

in-situ. These later served as cues for a more detailed web-based diary. Sohn et

al. [52] used an adaptation of the technique, as did Church et al. [10], where

the snippet technique was used in combination with experience sampling and a

diary study to explore daily information needs.

In the current study, snippets were used in combination with event-based

ESM, triggered by participants’ news reading. Participant responses to snippets

were used as the basis for more detailed diary questions, and also served as

memory cues during exit interviews. The user study consisted of three parts: (a)

an instruction email; (b) snippet and diary questions; and (c) an exit interview.

Fig. 1. Snippets and diary questions via the Wunderlist app

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in News Consumption 5

A Instruction email: Participants received an email that included the study

brief, installation and sign-up instructions for the Wunderlist app

4

, and ex-

planations on the types and timing of the questions that would be sent to

them along with examples of how to answer the snippets, seeing as the snip-

pets were designed to be more open and vague than the diary questions.

B Snippets and Daily Questions: Participants were sent two sets of questions

every day through Wunderlist–snippets and diary questions, over a period of

two weeks. Snippets were sent every morning, asking participants to add a

short text or a picture of the context in which they consumed news that day.

Sending times varied from one day to another, so as to minimize the poten-

tial cognitive bias associated with scheduled experience sampling alerts [13].

During the first 3-4 days of participation, instructions were given with ex-

amples (Fig. 1). In following days, the examples were removed. Four to five

diary questions were sent every evening. Questions were limited in number

so as not to impose too high a burden on participants, and were usually

open ended so as to not limit the scope of responses. While questions var-

ied in wording and order from one day to another, so they would not seem

repetitive to participants, they were focused on four relatively distinct areas.

Table 1 contains descriptions of these areas, as well as several examples for

questions participants were asked about them. Initially, all participants re-

ceived the same questions, which were modified from day to day in order to

attain more detailed information about participant habits. However, as the

goal of the study was exploratory and data analysis progressed throughout,

the diary questions were customized for each participant on a daily basis.

C Exit interviews: Upon the ‘snippets and diary questions’ phase completion,

participants were interviewed. Interviews were conducted either in person

or via Skype, and were audio-recorded for later transcription and analysis.

Each interview lasted between 20 to 30 minutes, and included three parts:

(a) general and demographic data such as age and occupation; (b) targeted

questions about the participant’s responses during the situated study; and

(c) questions about their experience regarding the data collection method.

3.1 Data Analysis

An iterative approach to data collection was taken, whereby collected snippets

and diary responses were sampled on a daily basis and compared to concepts and

insights that had begun to emerge. Interview audio was transcribed verbatim.

Transcripts were then thematically analyzed [5]:

Open Coding: snippets, diaries and interviews were coded line-by-line using

the NVivo qualitative data analysis software; pertinent statements were labelled.

Axial coding: relationships were identified between the concepts and cate-

gories that emerged during open coding. We sought to discern the phenomenon

4

https://www.wunderlist.com/

6 Y. Cohen et al.

Table 1. Diary Question Topics and Examples

Question Topic Examples

Triggers for news-reading experiences – What made you want to read (or listen to,

or watch) the news today?

– Why did you choose to read, watch or listen

to the news at this specific time? (more than

one answer is OK)

Environment and surroundings (e.g.

concurrent activities, distractions,

public or social settings)

– What did you like about your reading envi-

ronment? What did you dislike?

– Were you around others while reading? If

yes did this affect your reading in any way?

– Did anything bother or distract you while

reading? If so what was it?

Feelings about news consumption ex-

perience as a whole

– Did you find the experience: positive, nega-

tive or neither? (please explain if possible)

– Did reading the news affect your mood in

any way? If yes in what way?

Reasons for ending a news-reading

experience

– Why did you stop reading?

– What made you stop reading?

at hand (i.e. news consumption), with an additional emphasis on causal, con-

textual and intervening conditions, as these were the focus of the research, and

would be the basis for later analysis. Analytic memos were used to note and

highlight developing themes.

Themes were reviewed in a manner roughly corresponding to the six phases

of thematic analysis set out by Braun and Clarke [5], though the process was

recursive rather than linear, as noted by Braun and Clarke – we moved be-

tween phases as needed, repeating and re-evaluating themes and coded text as

necessary.

3.2 Participants

Participants were recruited through personal contacts, social network posts, and

notice-board adverts at three university campuses. The advert included infor-

mation about remuneration, inclusion criteria and a link to an online sign-up

form. The inclusion criteria required participants to live in the UK, be 18 years

of age or above, use an iPhone or an Android based-smartphone (for purposes of

compatibility with the data collection app), and read the news on a regular basis

using a digital device, so that digital consumption habits could be gauged. The

signup form asked respondents to enter contact and demographic information,

and included several questions intended to confirm that participants meet the

inclusion criteria. This information was also used to diversify the study sample

in terms of age, gender and students vs. non-students. It was also used to gauge

commute time. Each participant was remunerated with a small payment in cash

or transfer upon completion of the study, and one larger value Amazon voucher

was drawn between all participants.

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in News Consumption 7

Seventeen knowledge workers were recruited for the main user study (ten

female). Participant ages ranged from 22 to 47 (M=30, SD=8). Fourteen partic-

ipants lived in London, and three lived outside of it but commuted to the city

on a daily basis. Eleven participants were students, and six were professionals.

3.3 Apparatus

The Wunderlist platform was used to implement the diary study and the ‘snip-

pet’ technique/experience sampling components of the study. Wunderlist pro-

vides a basic tier of its platform and apps free of charge. Therefore, participants

were not required to pay for downloading or using the app.

Participants installed the Wunderlist app on their mobile phone, where they

would receive notifications of new snippets or diary questions, which they could

tap in order to view and respond to each of these respective items. The app

allows users to enter text in several fields: the ‘task’ fields adjacent to the task-

completion checkboxes, a ‘notes’ area for freeform entry of text, and a comments

thread. Users were not instructed where to answer, and were given the freedom

to answer as they chose. On the researcher’s side, participants were managed

from Wunderlist’s software for Mac, with each participant being added as a ‘list’

that was shared by the researcher with the participant. Both the researcher and

the participant could freely add, edit and annotate items on the list.

4 Results

4.1 Triggers for reading the news

Triggers were specific reasons described by participants for consuming news in

a particular situation.

Break from study or work

A theme with nearly universal prevalence among participants was the use of

news consumption as a break from a different activity that usually required a

higher level of concentration. Reading, rather than listening or watching, was

usually cited as the way in which news was consumed. A very frequently dis-

cussed rationale for reading news during a break was that it is an activity that

still requires engagement, but not at the level required by work or study.

“[...] it’s sort of a quality break [...] switching to something that’s relatively

similar, the same kind of concentration is involved, but it’s still different enough

that it provides a rest from what I was working on.” P2 - Interview

Many participants described reading the news as something that didn’t need

the same level of concentration as work, and therefore provided an opportunity

to restore their ability to focus:

“If I’m really burnt out I won’t absorb any of the news, but it gives me

something to focus on that’s not concentrated on writing or coding or any of the

other things that I’m supposed to be doingA few hours later I will be ‘what did I

read again?”’ P3 Interview

8 Y. Cohen et al.

Furthermore, a number of participants mentioned the discrete nature of news

content as being conducive to their subsequent resumption of work. For example,

P2 (Interview) explained: “[...] it also has a beginning and the end - when I finish

reading an article I go back to work. I can obviously read another article, but

that will extend it by only a little”.

Morning habit

A majority of participants indicated that they consume news in bed or while

preparing and eating breakfast. Participants described this behaviour as habit-

ual, except in unforeseen circumstances such as lateness or being in a hurry.

This morning habit is corroborated in a study conducted by Bhmer et al., which

found news apps to be the most popular in the morning [37].

Two reasons were generally cited. The first is, to use the term given by several

participants, ‘wanting to know what’s going on in the world’:

“When I just wake up and I want to know what’s going on in the world, so

in the morning I always check it [...] it’s a habit, because I wake up... I always

wake up quite early, so I can take my time to start easily, have my breakfast,

and while I have my breakfast I’ll scroll down the news.” P5 - Interview

The second reason for morning news consumption was procrastination. This

was cited either together or apart from the need to be updated about the news.

“Maybe it’s just that I don’t want to start immediately with working, and I

just need to ease myself into it” P2 - Interview

Notifications and widgets

Notifications are small displays of text that appear on a computing device,

usually a smartphone or a tablet, and alert the user to a certain occurrence or

event. Widgets are slightly larger ‘windows’ of content, that usually show a string

of informative text and an image or graphic; notifications are momentary and

disappear within a few seconds while widgets permanently reside on the user’s

screen until they are removed. Both served as triggers for news consumption.

Participant responses indicated that they frequently decided whether to tap

on a notification or widget to read a story in more depth. One indicated that this

decision depends on the type of story, and whether she is otherwise busy. At times

she will be content with consuming a news item exclusively via a notification.

“The push notifications from the Guardian app keep me informed without my

having to read the story (or do anything).” P11 - Snippet

This participant later explained in detail: “[...] ’England won the Ashes’.. I

don’t actually need more information than that, for example [...] It’s completely

dependent on how interested I am in the story and also what I’m doing at the

time [...] they pop up at any time during the day, and I dont always have the

liberty to check it immediately, because I’m doing something else, and sometimes

I forget what it was before I’ve come back.” P11 - Interview

Social feed skimming

Participants described a logic for news consumption via social media that is

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in News Consumption 9

similar to the one they described for notifications and widgets i.e. a triage of

whether to explore an item further or not.

“I pick up a lot of stuff that I read through the news feed of my Facebook

page, [...] I find that more convenient way of accessing it, because it’s sort of

summarized in the posts that appear in my news feed” P14 - Interview

“[I] scroll down and see if there’s anything interesting [...] If you’re interested

then you’ll click on it [...] If not then just on to the next one. So it’s just a quick

scan of things to see if something really interesting has happened” P14 - Interview

Waiting for people or technology

People were often triggered to look at news items when waiting either for people

or for processes to complete. This can be viewed news consumption filling ‘dead

times’ [46] or consumption of news in ‘interstices’ [20].

“[...] you’re waiting for a friend for like an hour or something [...] it becomes

a bit tedious, because I know that I’m using this just to fill time, as opposed to

when I’m actually interested in something to read. [...] sometimes I really enjoy

it when I’m actually saying ‘OK, I actually want to see what’s going on today’,

but other times it’s just because I don’t have anything to do... It’s just to check

whatever is going on there” P8 - Interview

Another participant discussed the effect of anticipation while waiting for

people more poignantly, but pointed out that he sees news reading as a more

productive ‘time-killing’ exercise than playing a game.

“[...] it’s really just killing time until something happens or until someone will

meet me; It can be a bit frustrating, because if it’s something that you are waiting

for and you know it starts at a certain time, you can kind of judge what you will

read, but if you’re waiting for someone, it’s frustrating - they’ll arrive and you

are halfway through reading something... Because I tend not to go back to things

as well, I think it’s not as much of a relaxing experience. It’s more killing time

in a more productive way than playing a game, which I do sometimes.” P14 -

Interview

Situations of waiting for a certain process or machine to finish were also noted.

The difference here, as opposed to waiting for a person, is that participants could

better gauge the beginning and end time of the waiting experience.

Media multitasking

Participants indicated that they sometimes read news on a digital device as

a secondary activity while consuming content in another medium, such as tele-

vision, but not being fully engaged (cf. [48, 49]) . One participant noted this

happens when he is watching a television show together with his partner, and

is not particularly interested in its content. In such a scenario of split attention

between different forms of media, he will continuously evaluate the perceived

benefit from each source and compare between them, terming this process as an

‘interest/engrossment trade-off’.

“I will definitely scan a bit between the two [...] I guess it depends on how

engrossed I am in either; I guess if the movie [...] has a slow part, then I’ll move

back to the news, and if the news is really interesting, then I’ll get engrossed

10 Y. Cohen et al.

in that and focused on that, and then once I’m done I’ll look back up and say

‘this is going on’ in the movie [...] I’ll go back and forth. So it’s about the in-

terest/engrossment trade-off between the two, which will make me go back and

forth.” P3 - Interview

4.2 Conducive contextual factors

We define conducive contextual factors as those that have a positive effect on par-

ticipants’ news consumption experiences. Participants generally described these

factors as being associated with a more pleasurable experience, and being more

receptive to richer and longer content.

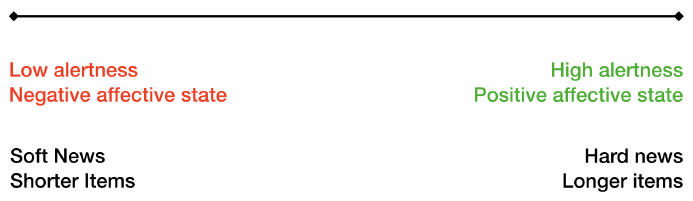

Alertness and mood

Many participants highlighted how their emotional or cognitive capabilities in

a given context are reflected in their likelihood of consuming ‘hard news’ - topics

such as war or government corruption, or ‘soft news’ - topics such as celebrity

news or ‘man bites dog’ stories [34]. This ‘suitability spectrum’ of hard news vs.

soft news to the affective state of a user is outlined in Fig. 2.

One participant stated that a low level of alertness greatly reduces her at-

tention and receptiveness to content, even to the point of stop reading.

“[...] that’s a big factor [being tired]. I know that if I start reading an article

and I’m tired I feel like I’m just LOSING IT, I feel like nothing is coming into

my brain.. Nothing is going in. So at that point I stop” P2 - Interview

Another participant stated that while she will sometimes read news before

she goes to sleep at night, she does not want to read upsetting stories .

“I won’t try to read anything too harrowing [before going to sleep], you know,

we’re talking just interesting stuff... I try not to read about ISIS before I go to

bed” P12 - Interview

Another participant described the positive end of this spectrum in reference

to reading a newspaper on Sunday.

“Sunday is like the one day where I [...] just relax in the morning, because I

just have such a busy life [...] that’s my treat for Sunday, to just be able to lie in

bed with a cup of tea and read the papers [...] I will read something much more

in-depth, and longer, because I have the luxury of the time.” P11 - Interview

Background activity

The issue of the suitability of different kinds of background activities for

news consumption was one that split participants. Some stated that background

sounds are conducive for working. Others expressed ambivalence towards back-

ground sounds while reading. Additionally, several participants were distracted

by background activity, though the types of factors that would cause this varied

between participants.

“I’m actually used to it for my studies [...] having music in the background. It

doesn’t divert my attention, it only makes me know there’s something playing in

the background; I can’t concentrate without it. So when I want to listen to music

and read the news, I stay concentrated, it doesn’t split my attention. I mean, it

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in News Consumption 11

Fig. 2. User state - News consumption spectrum.

does split my attention, but I’m focused on the news, not on the music.” P6 -

Interview

Another participant indicated that the background environment will affect

the type of media she will choose for news consumption.

“[...] when I’m just walking on the street, I cannot read something and con-

centrate, so I prefer to listen to the podcast.” P1 - Interview

Other participants noted visual and physical aspects of background activity

as most affecting their news consumption experience. Some suggested that visual

distractions were more detrimental to concentration than auditory ones.

“There was a lot of movement in the room, which I caught from the corner

of my eye, so that kind of broke my attention [...] It can be less distracting

[auditory stimulations], you can get into a sort of ‘zone’, where you tune it out.”

P2 - Interview

Other participants noted crowding as a detrimental factor to reading on

public transport. One noted that he perceives as a personal safety issue.

“If I’m standing somewhere super-crowded, I’m not going to grab my phone

and read the news, like on the bus [...] same with the overground [train] during

rush-hour. It can get packed and I’m not going to break out my phone [...] it’s

just uncomfortable to do so, and also someone can just grab it and walk away”

P3 - Interview

Another participant noted privacy aspects of standing within a dense crowd

on the train.

“I tend to see other people looking. You get the feeling like someone else is

also watching what you’re reading, and that’s not really nice and makes me a bit

uncomfortable.” P7 - Interview

It should be noted that even with the consensus among participants as to

the distracting effects of crowding, some participants viewed them as tolerable

and were not willing to forego news-reading unless the situation was extreme.

“Sometimes it’s hard to [...] it’s too crowded to even get your phone out and

have a look at it [...] it’s loud and it’s bumpy [...] you can’t really focus on what

you’re looking at, but equally it’s something to do while you’re spending those 12

minutes or however long on the tube.” P11 - Interview

12 Y. Cohen et al.

4.3 Negative contextual factors

We define negative contextual factors as those that hampered participants news

consumption experience, possibly causing them to alter it in some way, such as

changing to another device, but not to end it.

Connectivity

Lack of Internet connectivity was cited by participants as a factor that hampers

news consumption. They discussed various responses to this type of situation.

While dedicated article-saving apps such as Pocket

5

have been developed for

offline reading scenarios, a prevalent solution among study participants was to

open multiple tabs in their mobile Internet browser - an item ‘hoarding’ of sorts,

though one user did note his frustration at the lack of serendipitous discovery.

“Usually on the public transport, I open news sites in different tabs and I

activate it. So I find that not very comfortable, because in fact, I need to check

the link, it doesn’t go through because there is no signal.” P6 - Interview

Another participant noted the use of the offline mode in the news app she uses

on her phone. “[...] the Guardian app actually works offline, you just can’t get

the pictures and there’s certain content that you can’t get, but you can actually

get the stories, even if you haven’t got a signal, which is amazing, and really

good.” P11 - Interview

For several participants, switching to a print newspaper was the preferable

option in a situation of no connectivity.

“[...] if I’m on the tube as well, I tend to pick up the free papers... I read the

news that way, so there’s not much point in me looking at the BBC website when

I’m on the tube. And also, I can’t get reception [...]” P11 - Interview

As noted, some participants preferred to avoid the news consumption expe-

rience altogether when not connected.

“If I’m in the tube, I cannot access the Internet, so I don’t think I will do

anything if I was on the tube.” P1 - Interview

Suboptimal smartphone experience

There was a consensus among participants that news-reading on a phone, while

unavoidable on many occasions, did not provide what they perceived to be the

optimal experience. A prevalent reason cited for this is that the phone is not con-

ducive to serendipitous discovery of additional content. One participant, noting

that the reading experience itself was satisfactory, suggested that following links

was more difficult on the phone.

“The actual reading experience is fine when you’re reading an article that you

want to read and it’s just text [...] but I feel like it doesn’t facilitate easy links

into other similar things [...] You can kind of scroll down through the article and

there are related items on certain websites, at the bottom. I think it’s something

to do with the screen size, that it just feels very claustrophobic [...] If there

was something in there that you wanted to read more about, it’s not as simple

5

https://getpocket.com/

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in News Consumption 13

as opening another tab in your browser on your laptop, for example.” P14 -

Interview

Another commonly cited issue was that certain websites were not customized

for viewing on the small screen of the phone. One participant noted this in regard

to serendipitous discovery while reading another piece of news.

“[...] it’s also frustrating when people haven’t [...] translated things properly

for mobile, which happens quite a lot, where text doesn’t resize properly. All of

that sort of stuff makes it less, you know, comfortable.” P14 - Interview

It should be noted that this perception of inconvenience was not universal

among participants. Several, particularly younger, participants stated that a

smartphone is their preferred device to consume news. One noted that when

having the choice between her phone and a larger device such as a laptop, she

will still choose her phone.

“[...] for reading at home, it’s not on the computer; Basically, I will use my

mobile phone [...] while I’m using the computer and doing some professional

work like typing some important stuff, if I want to have some leisure time, I will

take my mobile phone and send some message to my friends and also look for

some news on my mobile phone.” P1 - Interview

Multitasking

Participants indicated that in certain situations, they will consume news while

performing another concurrent task. Concurrent tasks varied in both type and

location, but generally had the effect of splitting attention, thereby decreasing

engagement and making a breakaway from news consumption more likely.

One participant noted the effect of a concurrent task on the type of content

she will choose to consume.

“[...] if I’m reading on my phone [...] in between things and in a situation

where something else is going on, reading as a way to pass the time [...] If it’s

a story that requires me to think, to process what’s going on, what the page is

telling me, then I can’t really get into it that much.” P2 - Interview

Another participant noted productivity as a driver for multitasking while

consuming news, and reiterated the effect it has on the type of content consumed.

“[...] if I’m at home I tend to feel more comfortable reading or watching the

news when I’m doing something else [...] I tend to feel like I’m being unproductive

if I spend an extended period of time reading or watching the news, so I tend

to do it when I take a break from something else or am actually engaged in

doing something else, so I sometimes have the news channel on while I’m sort

of tidying up, or doing something that doesn’t require [...] intellectual focus [...].

When I’m consuming news while I’m doing something else, it tends to be smaller

articles or news.” P14 - Interview

The tentativeness of user engagement in news consumption was also noted in

the context of multitasking. One participant noted, in the context of reading on

public transport, that news will always be secondary in terms of cognitive effort.

This directly relates to the utilitarian role he assigned to news consumption.

“I don’t think that there are many news items I would completely block ev-

erything out and not quite notice there’s something else happening, it’s like [...]

14 Y. Cohen et al.

just a distraction half the time. If I’m going to catch up with the news, it’s really

not important.” P17 - Interview

Together, these statements indicate that there are instances in which par-

ticipants will knowingly and willingly enter a situation in which they are not

devoting their full attention to the news consumption experience, but it is nev-

ertheless viewed by them as an appropriate activity.

4.4 Barriers to use

Barriers are factors that lead to a situation where a user who would otherwise

consume news chooses not to. This includes while already consuming news and

choosing to end the experience, or alternatively choosing not to consume news

in a certain situation at all.

‘Me time’

Several participants described some instances of their travel time on public

transport as one in which they do not want to engage in any form of news

consumption, or even any other activity. They described these occurrences as

opportunities for introspection, reflection on their own thoughts, and even re-

laxation. In this scenario, participants would avoid consuming any sort of media.

“[...] sometimes when you’re walking and you’re on public transport, you just

want your mind to be clear.” P9 - Interview

Another participant described this experience not only as a way to ‘clear

the mind’, but also as an environment in which she is secluded from unwanted

individuals or pieces of information, despite being on a populated train.

“Sometimes I’ll just be ‘this is me time’ [...] no one can get me, I’m not going

to fill my head with more information, there’s enough going on around me, my

head’s spinning with stuff, I just can’t put any more stuff in it, even if it’s a

distraction, I need to relax my mind, and the train, for me, is the only place I

can actually do that.” P12 - Interview

While ‘me time’ describes a positive affective state, it was stated by partici-

pants as a reason for not consuming news, therefore is classified as a barrier.

News overload

Some participants described negative emotions triggered by cumulative or suc-

cessive instances of what they perceived as bad news, i.e. stories of a negative

nature. While all participants who described this chose to stop consuming news

as a result, the differences between them were in the intensity of emotions. One

participant was relatively vivid:

“there are days when [...] especially if there’s been a barrage of [...] Bad news,

recently... Sometime you just want to put your head in the sand and go ‘I don’t

want to know today’.” P11 - Interview

Another participant described a state of disinterest:

“most of the news I don’t find very interesting, like who killed who this week-

end or a famous person that died, you know, doing something stupid, I don’t find

that interesting.” P17 - Interview

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in News Consumption 15

Kinetosis

Several participants noted the issue of dizziness, nausea and an uncomfortable

physical feeling while using a digital device to read in a moving vehicle.

One participant noted that she resolves the issues by only reading books,

using a customized app that rectifies the motion-induced unpleasantness. This

could possibly indicate a desire to carry on with the reading experience despite

the physical obstacle, finding solutions to manage the issue.

“If I’m on public transportation I’ll read a book, I don’t usually read news. [...]

I have a tendency to get motion sickness, and reading a book... I have a particular

app on my phone that makes it very easy to read books, whereas reading pretty

much anything else is very. It gives me motion sickness.” P4 - Interview

Another participant indicated that she will avoid reading while she is stand-

ing on the train, as the simultaneous balancing and reading actions cause dizzi-

ness and nausea, however this does not occur when she is seated.

“[...] if it’s too crowded then I wouldn’t have a place to sit, I will have to hang

on to something like hold the rails or just try to balance myself, and I dont want

to read while I’m doing that, and usually I get this dizziness when I’m trying

to read while I’m balancing... So, I switch to music and I wont read while I’m

standing.” P7 - Interview

For another participant, the way to prevent dizziness is to eliminate reading

altogether and listen to a podcast instead:

“If I was on the bus, if I read news or if I read anything, I will feel dizzy,

so I prefer to listen to podcasts. Also, this applies to when I’m just walking on

the street, I cannot read something and concentrate, so I prefer to listen to the

podcast.” P1 - Interview

5 Discussion

5.1 Main Results

The current study discovered a variety of contextual factors that play an im-

portant role in news consumption, mostly of a phenomenological nature [21] -

relating less to informational and computational aspects of a given context, and

relating more to the social, cultural, affective and behavioural elements that

comprise an individual’s context of use.

The discovery of such contextual factors demonstrates the role of interpreta-

tion and sense-making processes on how users interact with technology, as well

as the dynamic, momentary nature of user actions within a given context. This

is especially noticeable in the fluid patterns of device use in relation to the space

in which they are being used, such as participants’ preference to read news on

their phone at home or at work.

These findings, coupled with a news experience increasingly shaped by mo-

bility, are important to the central finding of this paper–the creation of news

consumption ‘places’ by users. Participants indicated that they appropriate dif-

ferent spaces and devices to create contexts and environments for news consump-

tion that suit specific and dynamic momentary needs and affective states, often

16 Y. Cohen et al.

independently from physical location. These findings link to Harrison and Dour-

ish’s [27] discussion of the creation of place through situated meaning making.

5.2 Theoretical Implications

News consumption is opportunistic: Situation matters more than phys-

ical location

To a considerable degree, the findings of our study demonstrate that users

create their own meaningful contexts for news consumption, adapting and ap-

propriating a wide range of situations. In many, participants saw elements such

as background noise, lack of connectivity, waning alertness or an additional con-

current task not as barriers, but merely as detracting factors in an array of

considerations that shaped their news consumption experience. In certain in-

stances, factors such as suitability of news consumption to a specific situation

took precedence over other detracting factors, suggesting an interplay between

context, affective state, and consumption. In other cases, factors such as kine-

tosis (motion sickness) and the desire for ‘me time’ led to no news consumption

or even technology use at all.

The findings show that the factors affecting participants’ news consumption

habits were not only numerous, but also changed within an experience as a

perceived need to do so arose in ways that were situated [53]. In one example,

participants indicated that they changed their actions in-situ as a result of both

internal and external states. For example, participants indicated that when wait-

ing for other people, they will continuously adapt the type of content they read

in terms of topic and length, in order to suit the waiting time and level of con-

centration they predict they will have. Another example is in the case of media

multitasking, where concurrent activities of watching television and reading the

news encouraged a continuous in-situ reassessment of media consumption prefer-

ences, in what one participant described as an ‘interest/engrossment trade-off’.

Consumption characteristics are shaped by momentary needs and

states into consumption ‘niches’

Examined from a broad perspective, the results of this study indicate that mo-

mentary needs are a primary driver for news consumption. Participants generally

viewed news consumption as a break or leisure activity, which they engaged in

when they wanted to keep their mind busy, fill otherwise ‘dead time’ or in cases

where news consumption is a daily or weekly ritual. Importantly, in some cases,

such as daily or weekly rituals, the needs and context seemed to relate specifically

to supporting the consumption of news content.

While contextual findings were segmented for presentation purposes, the in-

terplay between the momentary needs that drove these factors was just as impor-

tant. For example, a situation where news consumption was triggered by waiting

for someone also included the distracting element of expectation. Participants

indicated that this had an effect both on the type of news they consumed and

on their level of concentration and immersion. It is this interplay that seemingly

connects physical environment, affective state, and type of news being consumed.

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in News Consumption 17

A needs-based approach is an essential part of the assumption that users

appropriate spaces for news consumption. In this appropriation process, users

essentially match a momentary need with the availability of opportunity to re-

alize that need, thereby creating their own unique news consumption ‘places’,

or ‘consumption niches’. Dimmick et al. [20] previously discussed the concept

of ‘niches’ in terms of time and space interstices in which users ‘fit’ their news

consumption, such as with their mobile devices while commuting, or on a desk-

top computer at work. By focusing on aspects of time and space, Dimmick

perhaps addresses elements inherent in a view of context as something to be

measured [20], rather than from the perspective of the individual experiencing

it. Indeed, Dimmick concludes his paper by defining it as a call for further explo-

ration into the intertwining of media consumption in mobile contexts and users

daily lives. The results of the current study add to Dimmick’s work by adding a

phenomenological layer of context to the theory of niches in news consumption.

The act of creating these ‘consumption niches’, and the needs that drive it, point

to news consumption being an opportunistic activity.

5.3 Practical Implications

As this study was exploratory, its goal is to serve as a starting point for future

exploration of the identified contextual factors. While today’s sensing technol-

ogy facilitates easy measurements of movement, lighting and latitude-longitude

coordinates, elements such as user alertness, mood and distraction are not yet

as easy to identify. However, significant advances are being made in classifying

factors such as user mood [35, 51, 24] and boredom [49] from smartphone and

wearable data, and it is likely that smartphones and wearable devices in the near

future might be able to robustly detect users’ affective state [29], which might

have significant implications for the development of new kinds of context aware

news applications. For example, the affective state of an individual could be

used as a proxy to whether they are receptive to content that is ‘hard news’, or

whether they will be more open to ‘soft news’. In other words, a classifier could

predict the ‘user-alertness’ based on user’s emotional state, mobility patterns,

or any other passive data.

Additionally, our work could expand the possibilities of previous adaptive

content models such as the one proposed by Billsus and Pazzani [4] and Tavako-

lifard et al. [54]. Just as importantly, it can expand upon the work started by

Constantinides et al. [14–16] by adding to the range of factors by which adap-

tive interfaces match a user’s habits, preferences and affective state. For example,

factors such as the ‘morning habit’, the ‘break from work or study’, the ‘media

multitasking’, the ‘connectivity’, and the ‘suboptimal smartphone experience’

could be easily identified from smartphones’ sensors. In turn, the raw sensors

signals could be translated into features to train models to detect these high-

level factors. Having such models will be of particular use, for example, in the

multitude of instances where contextual factors affected the length of text that

users would read. For example, more concise descriptions of news content could

be presented when users are more tired or distracted.

18 Y. Cohen et al.

5.4 Limitations

The current study is subject to several limitations in the design and the results

of the study. First, some of the methods used in the study carry the potential

for certain biases. Diaries, being a reflective and self-reported method, have

the potential for retrospective distortions [59]. Similarly, interviews are subject

to recall errors, seeing as they are retrospective conducted even longer after

participants’ actions have taken place. However, the use of memory cues during

interviews [42] and scheduling of the interviews as closely to the in-situ study

as possible [50] were designed to alleviate this. An additional memory-related

limitation pertains to the subset of users who, on several occasions, ‘aggregated’

snippets and diary questions and answered them all at once. While not rendering

the collected data unusable by any means, this behaviour effectively negates the

‘real-time’ qualities of ESM and the value of snippets as memory cues, leaving

the data as a traditional diary study. Similarly, there were also occurrences of

participants responding to snippets, diary questions or both on the following

day after they were sent. Seeing as uncued memory lasts for about one day [50],

this behaviour might introduce some additional retrospective distortions, though

supposedly not substantial ones. Finally, while the sample of 17 participants for

this study is relatively standard for self-reporting studies such as diary studies

and experience sampling, it would be ideal to further explore and gauge the

effectiveness of the methodology presented in this paper, both for situated studies

as a whole, and for news consumption and media studies in particular.

6 Conclusion

This study aimed to discover contextual factors that are of a qualitative nature,

and that are currently not addressed by ‘contextually-aware’ research and soft-

ware frameworks. The study produced findings that indicated a range of social,

cultural and individual factors that drive the manner in which users consume

news, and contextual factors. Most notably, the findings indicated that individu-

als often construct a context of use that is partially or wholly independent of the

space in which their interaction with technology is taking place, reinforces earlier

work by into the appropriation of spaces [27]. Participation rates and statements

indicated a low participation burden, true to the original study design goal.

These results can be of use to the wider HCI community by serving as a

starting point for further research into the phenomenological aspects of context,

and enabling the development of news and media consumption technologies that

will address these contextual factors, such as previous work into adaptive news

interfaces [14]. Additionally, this research may herald further work into the de-

sign of in-situ methods that lower participant data-entry burden, as well as the

appropriation of ‘off the shelf’ software applications for the purpose of in-situ

research.

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in News Consumption 19

References

1. Gregory D. Abowd, Anind K. Dey, Peter J. Brown, Nigel Davies, Mark Smith,

and Pete Steggles. 1999. Towards a Better Understanding of Context and Context-

Awareness. International Symposium on Handheld and Ubiquitous Computing,

304307. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-48157-5 29

2. Alia Amin, Sian Townsend, Jacco van Ossenbruggen, and Lynda Hardman. 2009.

Fancy a Drink in Canary Wharf? A User Study on Location-Based Mobile Search.

In IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (INTERACT ’09), 736749.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-03655-2 80

3. Marc Aug. 1995. Non-places: Introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity.

London: Verso.

4. Daniel Billsus and Michael J. Pazzani. 2007. Adaptive News Access. In The Adaptive

Web, 550570.

5. Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology.

Qualitative research in psychology 3, 2: 77101.

6. Joel Brandt, Noah Weiss, and Scott R. Klemmer. 2007. Lowering the Burden for

Diary Studies Under Mobile Conditions. In Extended Abstracts on Human Factors

in Computing Systems (CHI 07), 23032308.

7. Barry A. T. Brown, Abigail J. Sellen, and Kenton P. O’Hara. 2000. A Di-

ary Study of Information Capture in Working Life. In Proceedings of the

SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’00), 438445.

https://doi.org/10.1145/332040.332472

8. Scott Carter and Jennifer Mankoff. 2005. When Participants Do the Cap-

turing: The Role of Media in Diary Studies. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’05), 899908.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1054972.1055098

9. Scott Carter, Jennifer Mankoff, and Jeffrey Heer. 2007. Momento: sup-

port for situated ubicomp experimentation. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’07), 125134.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1240624.1240644

10. Karen Church, Mauro Cherubini, and Nuria Oliver. 2014. A Large-scale Study of

Daily Information Needs Captured in Situ. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human

Interaction (TOCHI), 21, 2: 10

11. Karen Church and Nuria Oliver. 2011. Understanding mobile web and mobile

search use in todays dynamic mobile landscape. In Proceedings of the 13

th

In-

ternational Conference on Human Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and

Services, 6776.

12. Karen Church and Barry Smyth. 2009. Understanding the intent behind mobile

information needs. In Proceedings of the 14

th

international conference on Intelligent

user interfaces (IUI ’09), 247256. https://doi.org/10.1145/1502650.1502686

13. Sunny Consolvo and Miriam Walker. 2003. Using the Experience Sampling Method

to Evaluate Ubicomp Applications. IEEE pervasive computing 2, 2: 2431.

14. Marios Constantinides, John Dowell, David Johnson, and Sylvain Malacria.

2015. Exploring mobile news reading interactions for news app personal-

isation. In Proceedings of the 17

th

international conference on Human-

computer interaction with mobile devices services (MobileHCI ’15), 457-462.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2785830.2785860

15. Marios Constantinides and John Dowell. A Framework for Interaction-driven User

Modeling of Mobile News Reading Behaviour. In Proceedings of the 26

th

Conference

on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, pp. 33-41. ACM, 2018.

20 Y. Cohen et al.

16. Marios Constantinides. Apps with habits: Adaptive interfaces for news apps. In

Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference Extended Abstracts on Human

Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 191-194. ACM, 2015.

17. Toon De Pessemier, Cdric Courtois, Kris Vanhecke, Kristin Van Damme, Luc

Martens, and Lieven De Marez. A user-centric evaluation of context-aware recom-

mendations for a mobile news service. Multimedia Tools and Applications 75, no. 6

(2016): 3323-3351.

18. David Dearman, Melanie Kellar, and Khai N. Truong. 2008. An Examination of

Daily Information Needs and Sharing Opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2008

ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW ’08), 679688.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1460563.1460668

19. Anind K. Dey. 2001. Understanding and Using Context. Personal and Ubiquitous

Computing 5,1: 47.

20. John Dimmick, John Christian Feaster, and Gregory J. Hoplamazian. 2010. News

in the Interstices: The niches of mobile media in space and time. New Media Society.

21. Paul Dourish. 2001. Seeking a foundation for context-aware computing. Human-

Computer Interaction 16, 2: 229241.

22. Paul Dourish. 2004. What We Talk About when We Talk About Context. Personal

and Ubiquitous Computing 8, 1: 1930.

23. Paul Dourish and Genevieve Bell. 2011. Divining a digital future: Mess and mythol-

ogy in ubiquitous computing. MIT Press.

24. Peter A. Gloor, Andrea Fronzetti Colladon, Francesca Grippa, Pascal Budner, and

Joscha Eirich. Aristotle Said “Happiness is a State of Activity”Predicting Mood

Through Body Sensing with Smartwatches. Journal of Systems Science and Systems

Engineering 27, no. 5 (2018): 586-612.

25. Erving Goffman. 1963. Behavior in public places: notes on the social organization

of gatherings. Free Press of Glencoe.

26. Simon Gottschalk and Marko Salvaggio. 2015. Stuck Inside of Mobile: Ethnography

in Non-Places. Journal of contemporary ethnography 44, 1: 333.

27. Steve Harrison and Paul Dourish. 1996. Re-place-ing Space: The Roles of

Place and Space in Collaborative Systems. In Proceedings of the 1996 ACM

Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW ’96), 6776.

https://doi.org/10.1145/240080.240193

28. Anthony Jameson. 2009. Adaptive interfaces and agents. Human-Computer Inter-

action: Design Issues, Solutions, and Applications.

29. Eiman Kanjo, Luluah Al-Husain, and Alan Chamberlain. Emotions in context:

examining pervasive affective sensing systems, applications, and analyses. Personal

and Ubiquitous Computing 19, no. 7 (2015): 1197-1212.

30. Mozhgan Karimi, Dietmar Jannach, and Michael Jugovac. News recommender sys-

temsSurvey and roads ahead. Information Processing Management 54, no. 6 (2018):

1203-1227.

31. Gabriella Kazai, Iskander Yusof, and Daoud Clarke. Personalised news and blog

recommendations based on user location, Facebook and twitter user profiling. In

Proceedings of the 39th International ACM SIGIR conference on Research and

Development in Information Retrieval, pp. 1129-1132. ACM, 2016.

32. Melanie Kellar, Carolyn Watters, and Michael Shepherd. 2007. A field study char-

acterizing Web-based information-seeking tasks. Journal of the American Society

for Information Science and Technology 58, 7: 9991018.

33. Adam Kucharski. 2016. Post-truth: Study epidemiology of fake news. Nature 540,

7634: 525.

Places for News: A Situated Study of Context in News Consumption 21

34. Sam N. Lehman-Wilzig and Michal Seletzky. 2010. Hard news, soft news, “general”

news: The necessity and utility of an intermediate classification. Journalism 11, 1:

3756.

35. Robert LiKamWa, Yunxin Liu, Nicholas D Lane, and Lin Zhong. 2013. Moodscope:

Building a mood sensor from smartphone usage patterns. In Proceedings of the

11

th

annual international conference on Mobile systems, applications, and services

(MobiSys ’13), 389-402. https://doi.org/10.1145/2462456.2483967

36. Clara Mancini, Keerthi Thomas, Yvonne Rogers, and Blaine A. Price. 2009.

From spaces to places: emerging contexts in mobile privacy. In Proceedings of

the 11

th

international conference on Ubiquitous computing (Ubicomp ’09), 1-10.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1620545.1620547

37. B¨ohmer Matthias, Brent Hecht, Johannes Schning, Antonio Krger, and Gernot

Bauer. 2001. Falling asleep with Angry Birds, Facebook and Kindle: a large scale

study on mobile application usage. In Proceedings of the 13

th

international confer-

ence on Human computer interaction with mobile devices and services (MobileHCI

’11), 47-56. https://doi.org/10.1145/2037373.2037383

38. B¨ohmer, Matthias, Gernot Bauer, and Antonio Krger. 2010. Exploring the design

space of context-aware recommender systems that suggest mobile applications. In

2nd Workshop on Context-Aware Recommender Systems.

39. Kristine S. Nagel, James M. Hudson, and Gregory D. Abowd. 2004. Predictors of

Availability in Home Life Context-mediated Communication.In Proceedings of the

2004 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW ’04),

ACM, 497506. https://doi.org/10.1145/1031607.1031689

40. Nic Newman and David Levy. 2015. The Reuters Institute Digital News Report

2015: Tracking the Future of News. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism,

University of Oxford.

41. Tien T. Nguyen, Pik-Mai Hui, F. Maxwell Harper, Loren Terveen, and Joseph A.

Konstan. 2014. Exploring the filter bubble: the effect of using recommender systems

on content diversity. In Proceedings of the 23

rd

international conference on World

Wide Web (WWW ’14), 677-686. https://doi.org/10.1145/2566486.2568012

42. David G. Novick, Baltazar Santaella, Aaron Cervantes, and Carlos Andrade. 2012.

Short-term Methodology for Long-term Usability. In Proceedings of the 30

th

ACM

International Conference on Design of Communication (SIGDOC ’12), 205212.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2379057.2379097

43. Stina Nylander, Ters Lundquist, Andreas Brnnstrm, and Bo Karlson. 2009. “Its

Just Easier with the Phone” – A Diary Study of Internet Access from Cell Phones.

In Pervasive Computing, 354371.

44. Ofcom. 2014. News consumption in the UK: 2014 report. Ofcom.

45. Eli Pariser. 2011. The filter bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you. Penguin,

UK.

46. Mark Perry, Kenton OHara, Abigail Sellen, Barry Brown, and Richard Harper.

2001. Dealing with Mobility: Understanding Access Anytime, Anywhere. ACM

Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) 8, 4: 323347.

47. Martin Pielot, Tilman Dingler, Jose San Pedro, and Nuria Oliver. 2015. When at-

tention is not scarce-detecting boredom from mobile phone usage. In Proceedings of

the 2015 ACM international joint conference on pervasive and ubiquitous computing

(UbiComp ’15), 825836. https://doi.org/10.1145/2750858.2804252

48. Jacob M. Rigby, Duncan P. Brumby, Sandy JJ Gould, and Anna L. Cox. Media

Multitasking at Home: A Video Observation Study of Concurrent TV and Mobile

Device Usage. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Conference on Inter-

active Experiences for TV and Online Video, pp. 3-10. ACM, 2017.

22 Y. Cohen et al.

49. John Rooksby, Timothy E. Smith, Alistair Morrison, Mattias Rost, and Matthew

Chalmers. Configuring Attention in the Multiscreen Living Room. In ECSCW 2015:

Proceedings of the 14

th

European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative

Work, 19-23 September 2015, Oslo, Norway, pp. 243-261. Springer, Cham, 2015.

50. Daniel M. Russell and Ed H. Chi. 2014. Looking Back: Retrospective Study Meth-

ods for HCI. In Ways of Knowing in HCI, 373393.

51. Sandra Servia-Rodrguez, Kiran K. Rachuri, Cecilia Mascolo, Peter J. Rentfrow,

Neal Lathia, and Gillian M. Sandstrom. Mobile sensing at the service of mental

well-being: a large-scale longitudinal study. In Proceedings of the 26th Interna-

tional Conference on World Wide Web, pp. 103-112. International World Wide Web

Conferences Steering Committee, 2017.

52. Timothy Sohn, Kevin A. Li, William G. Griswold, and James D. Hollan.

2008. A Diary Study of Mobile Information Needs. In Proceedings of the

SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’08), 433442.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357125

53. Lucy A. Suchman. 1987. Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-

Machine Communication. Cambridge University Press.

54. Mozhgan Tavakolifard, Jon Atle Gulla, Kevin C. Almeroth, Jon Espen Ingvaldesn,

Gaute Nygreen, and Erik Berg. 2013. Tailored news in the palm of your hand: a

multi-perspective transparent approach to news recommendation. In Proceedings of

the 22

nd

International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW ’13 Companion),

305308. https://doi.org/10.1145/2487788.2487930

55. Alex S. Taylor. 2009. Ethnography in Ubiquitous Computing. In Ubiquitous Com-

puting Fundamentals, John Krumm (ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC, 203236.

56. John Urry. 2007. Mobilities. Wiley.

57. Wen-Chia Wang, 2017. Understanding user experience of news applications by Tax-

onomy of Experience (ToE). Behaviour Information Technology, 36(11), pp.1137-

1147.

58. Oscar Westlund. 2008. From Mobile Phone to Mobile Device: News Consumption

on the Go. Canadian Journal of Communication 33, 3: 443

59. Daniel A. Yarmey. 1979. The Psychology of Eyewitness Testimony. FreePress