© 2004 International Monetary Fund May 2004

IMF Country Report No. 04/126

New Zealand: Financial System Stability Assessment,

including Reports on the Observance of Standards and Codes on

the following topics: Monetary and Financial Policy Transparency,

Banking Supervision, and Securities Regulation

This Financial System Stability Assessment on New Zealand was prepared by a staff team of the

International Monetary Fund as background documentation for the periodic consultation with the

member country. It is based on the information available at the time it was completed on April 8, 2004.

The views expressed in this document are those of the staff team and do not necessarily reflect the

views of the government of New Zealand or the Executive Board of the IMF.

The policy of publication of staff reports and other documents by the IMF allows for the deletion of

market-sensitive information.

To assist the IMF in evaluating the publication policy, reader comments are invited and may be

sent by e-mail to publicationpolicy@imf.org

.

Copies of this report are available to the public from

International Monetary Fund ● Publication Services

700 19th Street, N.W. ● Washington, D.C. 20431

Telephone: (202) 623 7430 ● Telefax: (202) 623 7201

E-mail: publicati[email protected]g

● Internet: http://www.imf.org

Price: $15.00 a copy

International Monetary Fund

Washington, D.C.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

NEW ZEALAND

Financial System Stability Assessment

Prepared by the Monetary and Financial Systems and Asia Pacific Departments

Approved by Tomás J. T. Baliño and Daniel Citrin

April 8, 2004

This Financial System Stability Assessment is based primarily on work undertaken during a visit to New Zealand

and Australia from October 30 to November 18, 2003. The mission comprised Anne-Marie Gulde-Wolf (mission

chief), Paul Kupiec (deputy mission chief), Barbara Baldwin, Matthew Jones, Jodi Scarlata, Antonio Garcia

Pascual, and Charmane Ahmed (all IMF/MFD); Abdelhak Senhadji (IMF/APD); Michael Ainley (banking

supervision expert, U.K. FSA), Janet Holmes (securities expert, Ontario Securities Commission), and Barry Topf

(foreign exchange expert, Bank of Israel). The main findings of the mission are:

• New Zealand has a profitable and well-functioning financial system, operating in a framework of well-

developed financial markets. Short-term risks to stability appear low, given the favorable macroeconomic

outlook, and sound and transparent financial policies. Stress tests for systemically important banks show

resilience consistent with the sector’s relatively high levels of capital and profits. Dynamic stress tests

involving shocks to agriculture and to external funding show more persistent effects on bank profits, but do not

raise systemic concerns.

• New Zealand’s approach to banking regulation is based on disclosure and market discipline, and employs

limited prudential requirements. The sole supervisory objective is to ensure systemic stability. Given the high

share of foreign ownership, home-country supervision may also act as an additional discipline on bank

behavior. Notwithstanding the clear strength of the present framework, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand

(RBNZ) would benefit from increased real-time knowledge of potential stress in the banking system.

• The absence of a depositor-protection mandate, along with the foreign ownership of all systemically important

banks, would pose unique challenges to the RBNZ if a financial crisis were to occur. The high level of

Australian bank ownership suggests that the successful management of systemic challenges will also require

close cooperation with the Australian authorities. The RBNZ has been reviewing possible crisis management

options and has intensified trans-Tasman cooperation in banking regulation and failure management.

• Recent reforms in securities regulation and the restructuring of the New Zealand Stock Exchange (NZX) have

strengthened the securities regulatory framework. To fully implement the IOSCO Principles would require:

(i) a stronger regime for prevention and detection of market abuse; (ii) a more robust supervisory regime for

market intermediaries and collective investment schemes; (iii) improvements to the disclosure regime for

issuers; and (iv) stronger public oversight of private sector monitors.

The mission members drafted this report.

FSAPs are designed to assess the stability of the financial system as a whole and not that of individual

institutions. They have been developed to help countries identify and remedy weaknesses in their financial sector

structure, thereby enhancing resilience to macroeconomic shocks and cross-border contagion. FSAPs do not

cover risks specific to individual institutions, such as asset quality, operational or legal risks, or fraud.

- 2 -

Contents Page

Glossary .....................................................................................................................................4

I. Executive Summary and Overall Stability Assessment .........................................................5

II. Macroeconomic, Financial Sector, and Regulatory Context.................................................7

A. Macroeconomic Background ....................................................................................7

B. Financial Sector Context ...........................................................................................7

C. Supervision and Regulation ....................................................................................14

III. Short-Term Stability Issues................................................................................................16

A. Stress Testing the Financial System........................................................................16

B. Nonbank Financial Institutions ...............................................................................20

C. Foreign Currency Exposure and Functioning of Exchange Markets ......................21

D. Money and Bond Markets.......................................................................................22

E. Systemic Liquidity Provision ..................................................................................23

IV. Medium-Term and Structural Issues .................................................................................24

A. Banking Supervision...............................................................................................24

B. Crisis Management..................................................................................................25

C. Cooperation with Australia .....................................................................................26

Tables

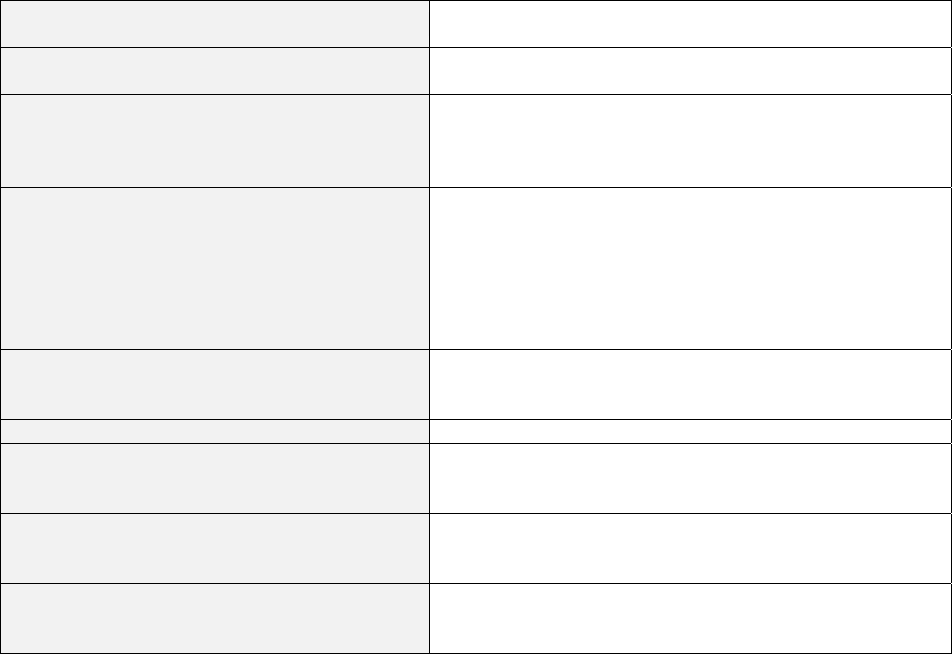

1. Principal Recommendations ..................................................................................................6

2. New Zealand: Selected Macroeconomic Indicators, 1999–2003 ..........................................8

3. New Zealand: Financial Soundness Indicators, 1999–2003..................................................9

4. New Zealand: Financial System Structure, 2000–02...........................................................11

5. Sensitivity Stress-Test Scenarios .........................................................................................18

6. Market Risk Results.............................................................................................................18

7. Credit Risk Results ..............................................................................................................19

8. Model Assumptions .............................................................................................................19

Figures

1. Foot and Mouth Disease Scenario .......................................................................................20

2. Funding Shock Stress Scenario............................................................................................20

Annexes

I. Observance of Financial Sector Standards and Codes—Summary Assessments ................28

Annex Tables

1. Recommended Action Plan to Improve Observance

of

the Basel Core Principles.............32

2. Recommended Action Plan to Improve Observance of IMF’s MFP Transparency Code

PracticesMonetary Policy ............................................................................................36

- 3 -

3. Recommended Action Plan to Improve Observance of IMF’s MFP Transparency Code

PracticesBanking Supervision .....................................................................................38

4. Recommended Action Plan to Improve Observance of IMF’s MFP Transparency Code

PracticesSecurities Regulation.....................................................................................41

5. Recommended Action Plan to Improve Observance of the IOSCO Principles...................44

GLOSSARY

APG Asia Pacific Group on Money Laundering

APRA Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority

ASRB Accounting Standards Review Board

BCP Basel Core Principles

CAR capital adequacy ratios

CIS collective investment schemes

ESAS Exchange Settlement Account System

FATF Financial Action Task Force

FSA Financial Services Authority

FSAP Financial Sector Assessment Program

GAAP Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

IAS International Accounting Standards

ICANZ Institute of Chartered Accountants of New Zealand

IOSCO International Organization of Securities Commissions

LoLR Lender-of-last Resort

MED Ministry of Economic Development

MFP Code IMF Code of Good Practices on Transparency in Monetary

and Financial Policies

MOU Memorandum of understanding

NBFI Nonbank financial institutions

NZD New Zealand Dollar

NZFOE New Zealand Futures and Options Exchange

NZX New Zealand Stock Exchange Limited and/or New Zealand

Stock Exchange (as appropriate)

OCR official Cash Rate

PTA Policy Targets Agreement

OMO open market operations

RBNZ Reserve Bank of New Zealand

RC Registrar of Companies

ROSCs Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes

SC Securities Commission

SDDS Special Data Dissemination Standard

SFE Sydney Futures Exchange

SRO Self-regulatory organization

TP Takeover Panel

- 5 -

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND OVERALL STABILITY ASSESSMENT

1. The New Zealand financial sector is dominated by institutions that are based in

Australia. Supervisory practices are based on a liberal disclosure-based regime, with

limited supervisory intervention. The low savings rate creates a large dependency on

foreign funding. In the absence of appropriate controls, these structural features have the

potential to engender vulnerabilities.

2. The favorable macroeconomic outlook, the profitable and well-functioning

financial system, and overall sound and transparent financial policies mitigate the

aforementioned vulnerabilities, and make short-term risks appear low. New Zealand’s

large net foreign indebtedness position owes entirely to private sector borrowings. Its strong

sovereign rating reflects prudent fiscal policies and no net foreign-currency debt. The

strength of the financial system reduces concerns about the lack of an active supervisory

framework. In the medium and longer run, supervisory enhancements are recommended to

ensure that an adequate framework to monitor and support financial stability remains in

place.

3. The mission’s main findings can be summarized as follows:

• The five foreign-owned banks that dominate the financial system are profitable and

well capitalized. For these institutions, the discipline of New Zealand’s market-based

disclosure regime is supplemented by active home country supervision.

• The foreign exchange market has allowed the private sector to manage its foreign

exchange risks and secure cover from a diverse set of counterparties under a wide

range of market conditions. Foreign exchange hedging is widespread.

• Stress tests show resilience in the banking sector, consistent with the sector’s high

levels of capital and profits. Significant exchange rate swings and house price

declines could be absorbed by all big banks. Dynamic stress test scenarios involving

shocks to agriculture and to external funding costs show more persistent effects on

bank profits, but do not raise systemic concerns.

• Banking supervision is based on disclosure and market discipline, with the sole

objective of ensuring systemic stability. The supervisory regime employs limited

prudential requirements, with no active on-site role for supervisors. The benefits of

this regime include low compliance costs, greater flexibility for financial institutions,

an enhanced role for market discipline, and reduced moral hazard risks. The ongoing

strength of the financial system has reduced concerns about the lack of an active

supervisory component.

• The absence of a depositor-protection mandate, along with the foreign ownership of

all systemically important banks may pose unique challenges for the RBNZ if a

financial crisis were to occur. Outsourcing of New Zealand bank operating systems to

parent institutions and Australian depositor preference law may complicate crisis

- 6 -

management. These risks have been recognized and control measures are being

analyzed. Efforts underway to improve cooperation with the Australian authorities are

welcome.

• Nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs), while not systemically important, are also

profitable. Overseas regulators provide additional supervision for a handful of the

largest nonbank institutions, which account for around half of the assets of the sector.

• Securities markets are relatively small, with trading and ownership concentrated

offshore. Restructuring of the New Zealand Stock Exchange (NZX) and reforms in

regulation have strengthened the regulatory framework, but some gaps remain that

may delay early detection and enforcement actions against improper conduct.

Table 1. Principal Recommendations

1

Issue Recommendation

Disclosure-based regime Maintain the quality, scope, and timeliness of disclosure to

ensure it continues to meet best international practice.

Importance of independent

directors

Fit-and-proper criteria should continue to apply in a

comprehensive manner. The RBNZ could offer independent

bank directors the possibility of discussing areas of concerns

without absolving directors of their statutory responsibilities.

Surveillance For banks, monitor more regularly liquidity and large exposure

early warning indicators. Consider commissioning third-party

reports and establish a small specialist team to make focused,

on-site visits on particular aspects of credit and operational risk.

Bank resolution and crisis

management

Review possible approaches to bank resolution, and the

operational and legal consequences that might arise, with a

view to establishing internal operational guidelines.

Nonbank supervision Review practices and resource needs for the government

agencies involved in oversight, especially the offices of the

Registrar and the Government Actuary, with a view towards

enhancing public access to timely and comprehensive data.

Securities markets regulation Enhance regulatory framework by including minimum

standards of conduct for collective investment scheme

operators, improving reporting mechanisms, strengthening

standards and penalties relating to market abuse, and

strengthening oversight of market intermediaries that are not

exchange members.

1

More specific suggestions are discussed at the appropriate places in the main body of the

report and in the standards assessments.

- 7 -

II. MACROECONOMIC, FINANCIAL SECTOR, AND REGULATORY CONTEXT

A. Macroeconomic Background

4. New Zealand has a resilient macroeconomic framework, benefiting from a series

of reforms undertaken over the past 20 years. Key features include a floating exchange

rate, deregulated financial markets, far-reaching privatization, a sound and transparent

medium-term framework, and an inflation-targeting framework under an independent central

bank. These factors, combined with favorable economic conditions, have underpinned New

Zealand’s strong real GDP growth rate of nearly four percent per annum since 1999.

5. Within the above framework, New Zealand has, in the recent past, seen

significant capital inflows to compensate for persistent low savings rates. The country

has accumulated a relatively high level of foreign debt, and gross debt now exceeds

100 percent of GDP, with the bulk of this being owed by the private sector. Given the

conservative fiscal stance, foreign capital inflows are matched by high private sector

borrowing from the banking sector. The strong sovereign rating reflects prudent fiscal

policies and no net foreign currency debt by the public sector.

6. Recent macroeconomic conditions have been favorable, even though the

continuing appreciation of the New Zealand Dollar (NZD) may dampen external

performance. Strong domestic demand contributed to high-capacity utilization rates, and

unemployment reached a 16-year low in 2003. Inflation declined to about 1½ percent in the

year to December 2003, reflecting the impact of the currency appreciation. The currency has

appreciated by 66 percent against the U.S. dollar and 36 percent on a trade weighted basis

between December 2001 and February 2004. The current account deficit is approaching a

three-year high of 4½ percent of GDP, reflecting the relatively strong cyclical position of the

New Zealand economy and the substantial appreciation of the NZD (Table 2).

B. Financial Sector Context

7. New Zealand’s financial sector and its regulatory environment underwent

significant changes over the past two decades. Previously dominated by publicly-owned

banks, which operated in a tightly regulated market, the sector is now almost fully in private,

foreign ownership, and the scope of regulation has been radically reduced from that of the

mid 1980s. NBFIs and securities markets have declined in importance and are now secondary

players, as banks have expanded their range of activities.

The banking sector

8. The banking sector includes 18 registered banks and, at end-2002, held assets

exceeding $NZ 200 billion (about 160 percent of GDP). Only two smaller banks are New

Zealand-owned, including a recently formed retail bank that is owned by the

government-owned post office (NZ Post). Ten banks operate as foreign branches, five are

local subsidiaries of foreign parent banks, and one is a joint venture between a foreign bank

and a local company.

- 8 -

Table 2. New Zealand: Selected Macroeconomic Indicators, 1999–2003

(End of period, unless otherwise stated)

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

Total population (million, end-2002) 3.942

GDP per capita (2002) in USD 16,762

Real sector

Real GDP (percentage change) 4.0 3.9 2.7 4.3 3.5

Nominal GDP (in NZD billion) 105.7 112.3 120.5 126.4 133.1

CPI inflation (e.o.p.) 0.5 4.0 1.8 2.7 1.6

Household savings ratio (in percent of disposable income) 4.8 -0.8 -4.4 -3.1 -8.2

Monetary and credit data (change in annual averages)

Monetary base 19.0 8.9 9.6 9.2 6.6

Money (M1) 19.5 6.9 15.3 12.8 7.8

Broad money (M3) 3.5 3.4 13.5 11.9 6.1

Domestic credit 8.3 8.5 7.6 12.1 5.3

Yield on government bills 5.2 6.7 5.9 5.8 5.4

Yield on government bonds 6.4 6.9 6.4 6.4 5.8

Reference bank lending rate 1/ 8.5 10.2 9.9 9.8 9.8

Yield spread, 90-day to 10-year bonds (b. p., end of period) 166 -66 191 13 41

Stock market index (percent change, end of period) 6.8 -13.8 8.0 -5.1 25.6

Public finances (in percent of GDP)

Central government financial balance (operating balance) 1.5 1.3 1.6 1.7 3.0

Central government net of revaluations and accounting

changes

0.2 0.8 1.8 2.2 4.3

External sector (levels, unless otherwise indicated)

USD exchange rate (end of period) 0.52 0.44 0.42 0.53 0.66

Trade balance (NZD billion) -0.8 1.4 3.1 0.7 -1.5

Current account (NZD billion) -6.7 -5.5 -3.1 -4.7 -5.9

Foreign direct investment (Net, NZD billion) 0.6 2.0 3.0 0.4 ...

Portfolio investment (Net, NZD billion) -3.0 -0.7 0.4 1.8 ...

Gross official reserves, e.o.p. (USD billion) 4.5 3.9 3.6 4.8 5.1

Reserve cover (expressed in months of imports) 2/ 2.5 2.4 2.6 2.3 3.7

Reserve cover (short-term external debt) 17.7 15.9 15.0 13.0 16.3

Total external debt (NZD billion) 102.9 99.9 110.2 108.8 103.9

of which: Public sector debt (NZD billion) 3/ 17.4 17.3 16.7 18.5 18.7

of which: Banking sector debt (NZD billion) - loans only ... 60.3 70.6 71.4 76.0

Central bank short-term foreign-currency liabilities

(NZD billion) 4/

0.7 1.4 0.7 1.0 0.7

Sources: Statistics New Zealand, RBNZ, New Zealand Stock Exchange, and New Zealand Treasury.

1/ This is a surveyed retail interest rate and represents a “base” lending rate offered to new business borrowers,

weighted by each surveyed institution’s total NZ dollar claims.

2/ Imports of goods and services (excluding factor income).

3/ Annual figures for 1998 and 1999, December quarter for 2000–02, June quarter for 2003.

4/ Remaining maturities of one year or less.

- 9 -

Table 3. New Zealand: Financial Soundness Indicators, 1999–2003

(In percent, unless otherwise indicated)

1999 2000 2001 2002 Jun-03 Sep-03

Banking sector 1/

Total system assets (NZD billion) 158.4 180.1 189.6 204.5 212.5 ...

Total assets of locally incorporated banks (NZD billion) 107.9 116.0 126.7 135.2 142.5 ...

Share of system assets in foreign branches 31.9 35.6 33.2 33.9 32.9 ...

Capital adequacy 2/

Tier 1 regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets (weighted average) 7.1 7.7 7.6 8.5 8.6 ...

Minimum observed tier 1 regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets 6.5 6.7 6.3 7.1 7.7 ...

Total regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets (weighted average) 10.3 11.1 10.7 11.3 11.4 ...

Minimum observed total regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets 9.6 9.6 9.5 10.5 10.3 ...

Aggregate system equity to aggregate system assets 3.2 2.8 2.7 2.5 2.4 ...

Aggregate equity asset ratio for locally incorporated banks 4.6 4.3 4.0 3.7 3.5 ...

Asset composition

Investments as a percentage of total system assets

Balances with central banks and other financial institutions 4.0 3.9 4.4 3.7 3.8 ...

Government bond holdings 1.8 1.7 1.4 1.5 1.3 ...

Other trading securities 7.6 6.5 5.9 5.8 5.0 ...

Total liquid assets 13.4 12.1 11.7 11.0 10.1 ...

Loans, advances and lease finance 77.0 72.9 75.8 75.9 75.9 ...

Sectoral distribution of loans to total loans

Households 47 46 45 45 47 48

Financial sector 1/ 7 6 5 6 5 4

Insurance sector 1/ 1 0 0 0 0 0

Construction sector 1/ 1 1 1 1 1 1

Communications sector 1/ 1 0 0 0 0 0

Non-residents 1/ 7 11 13 14 13 12

Mortgage loans (residential and commercial) 1/ 50 58 56 57 59 59

Aggregate risk-weighted assets to total assets 1/ 67 64 65 64 63 63

Asset quality and provisioning

Aggregate impaired assets to total assets (in basis points) 1/ 34.1 30.4 31.7 25.4 28.1 ...

Aggregate impaired and past due assets to total assets (in basis points) 47.8 44.8 88.4 53.6 55.7 ...

Aggregate total provisions to total assets (in basis points) 3/ 43.7 39 36.3 35.3 43.1 ...

Aggregate specific provisions to total assets (in basis points) 3/ 12.7 10.3 8.1 9.5 8.8 ...

Aggregate total provisions to total impaired and past due assets 3/ 91.4 87.1 41.1 65.9 77.4 ...

Aggregate specific provisions to impaired assets 3/ 37.2 33.9 25.4 37.4 31.3 ...

Earnings and profitability

Profit before tax and provisions to average assets 1.5 1.5 1.7 1.9 2.0 ...

Profit after tax and extraordinary items to average assets 1.1 1.1 1.1 1.3 1.3 ...

Profit after tax and extraordinary items to average equity 22.5 24.0 24.6 26.1 24.2 ...

Interest margin 2.4 2.3 2.3 2.6 2.6 ...

Noninterest income to total revenues 36.1 37.8 36.7 32.4 32.4 ...

Total operating expenses to total revenues 56.9 54.8 48.4 45.5 44.0 ...

Funding and liquidity

Liquid assets to total assets 13.4 12.1 11.7 11.0 10.1 ...

Liquid assets to deposits and other borrowings 28.6 26.9 23.7 22.3 19.8 ...

Loans, advances, and lease finance to deposits and other borrowings 105.2 105.9 102.2 101.6 100.2 ...

- 10 -

Table 3. New Zealand: Financial Soundness Indicators, 1999–2003 (continued)

(In percent, unless otherwise indicated)

1999 2000 2001 2002 Jun-03 Sep-03

Funding and liquidity (continued)

Loans, advances, and lease finance to NZD retail funding 192.8 195.5 188.1 186.0 185.0 ...

Liabilities to related entities to total liabilities 16.2 19.3 15.5 12.7 11.1 ...

Share of total liabilities owed to nonresidents 29.2 31.0 33.9 30.5 29.0 29.3

FX denominated liabilities to total liabilities 21.9 22.5 22.6 18.2 19.4 19.3

Share of FX denominated liabilities owed to related entities 53.5 39.2 47.5 37.5 33.0 33.0

Banking sector sensitivity to market risk

Avg. peak end-of day interest rate exposure as a share of equity 4/ 1.9 1.6 1.5 1.4 1.4 ...

Avg. end-of period interest rate exposure as a share of equity 4/ 1.5 1.3 1.2 1.3 1.1 ...

Avg. peak end-of day FX exposure as a share of equity (b.p.) 4/ 5/ 6.8 7.8 6.1 6.2 10.3 ...

Avg. peak end-of day equity exposure as a share of equity (b.p.) 4/ 0.6 0.6 1.8 1.2 0.6 ...

Insurance sector indicators -Life Insurance

Growth rate of gross premiums written (% change from last year) 3.9 -8.6 -5.3 2.9 ... ...

Life Surplus to Total Assets 13.0 12.0 13.9 16.6 ... ...

Investment income / Investment assets 9.5 6.4 2.8 -3.1 ... ...

Insurance sector indicators - Non Life Insurance

Growth rate of gross premiums written (% change from last year) 3.8 4.9 -2.2 4.3 ... ...

Combined ratio 99.1 100.0 101.3 98.5 ... ...

Investment income to investment assets 4.9 6.3 5.5 4.0 ... ...

Underwriting profit to net investment income 16.4 -0.2 -18.7 42.6 ... ...

Solvency Margin 63.5 61.8 67.2 59.7 ... ...

Household sector indicators

Rate of growth of assets 5.9 1.2 4.6 9.0 ... ...

Rate of growth of liabilities 10.5 6.8 8.0 10.0 ... ...

Rate of growth of housing value 5.2 1.0 5.2 14.8 ... 23.8

Rate of growth of personal bankruptcies -6.9 -8.6 8.6 -10.4 ... 3.8

Net financial assets to disposable income 72.6 67.2 60.8 47.6 ... ...

Debt servicing cost to disposable income 8.0 9.1 8.4 9.0 ... 9.2

Corporate sector indicators

Corporate debt to equity ratio 87.9 93.2 96.4 95.0 ... ...

Growth rate of company liquidations -29.7 -22.6 -26.9 -47.2 ... ...

EBITDA to interest expenses 248.7 251.8 257.9 325.1 ... ...

ROA 4.0 3.7 3.6 4.6 ... ...

ROE 9.5 9.5 9.6 12.4 ... ...

Current ratio 127.9 121.0 124.3 130.5 ... ...

Source: Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Ministry of Economic Development, Statistics New Zealand.

1/ Excludes interbank exposures, NZD claims for residents, all non-resident claims.

2/ Includes only local incorporated banks.

3/ Excludes interbank exposures. June 2003 flow data represent 12 month running totals.

4/ Simple average of order in council market risk measures. June 2003 flow data represent 12 month running totals.

5/ 1998 average excludes one small bank with an extreme reported value.

- 11 -

Table 4. New Zealand: Financial System Structure, 2000–02

(End of period, unless otherwise stated)

Number Assets

(NZD billion)

Percent of

Total Assets

2000 2001 2002 2000 2001 2002 2000 2001 2002

Banks

18 17 17

180.1 189.6 204.5 70.7 71.2 73.6

Domestic 1 2 2

1.4 1.7 2.2 0.5 0.6 0.8

Foreign-owned branches 11 10 10

64.2 62.3 69.3 25.2 23.4 24.9

Foreign-owned, incorporated locally 6 5 5

114.6 125.0 133.0 45.0 46.9 47.8

Nonbanks

311 303 290 74.5 76.8 73.5

29.3 28.8 26.4

Managed funds 1/ 56 56 56

47.5 47.9 44.4 18.7 18.0 16.0

Life insurance companies 39 40 36

12.4 12.0 10.7 4.9 4.5 3.8

Non-life insurance companies 85 83 75

3.7 4.0 3.5 1.5 1.5 1.3

Finance companies 46 48 50

6.0 7.7 9.2 2.4 2.9 3.3

Building societies 2/ 10 10 11

2.4 2.6 2.9 0.9 1.0 1.0

Credit unions 74 65 61

0.4 0.4 0.4 0.2 0.2 0.1

Bonus Bonds Trust 1 1 1

2.1 2.2 2.4 0.8 0.8 0.9

Total financial system

329 320 307

254.6 266.4 278.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Sources:

Banks - Individual Bank Disclosure statements.

Superannuation - Government Actuary annual report, with 2002 estimated from RBNZ partial survey data.

Managed funds - RBNZ quarterly and annual surveys.

Life insurance companies & Non-life insurance companies - MED, Insurance and Superannuation Unit.

Finance companies - Reserve Bank, Annual Statistical Return and Reserve Bank Bulletin June 2003.

Building societies - Reserve Bank, Annual Statistical Return.

Credit unions - Report of the registrar of credit unions.

1/ Managed funds (superannuation, unit trust, group investment funds, excluding insurance companies): data are funds

under management. Include ten large charities as fund managers.

2/ Building societies have added to them the Public Service Investment Society (PSIS), a similar kind of savings

intermediary.

9. New Zealand’s banking sector is profitable and well capitalized. Over the last five

years aggregate industry return on assets has exceeded 1½ percent, and after-tax returns on

equity have consistently exceeded 20 percent. Capitalization, whether measured by

equity-asset ratios or by regulatory capital measures, is above international minimum

prudential benchmarks. The aggregate equity-asset ratio of locally incorporated banks is

4.6 percent. Tier 1 regulatory capital adequacy ratios (CARs) are all in excess of 8.5 percent

and total CARs are approaching 11.5 percent (Table 3). Among registered banks, the least

well-capitalized institution has a Tier 1 CAR of 7.7 percent and a total CAR of 10.3 percent.

Impaired assets are low, comprising only slightly more than 0.5 percent of bank assets.

- 12 -

General and specific provisions cover about three-quarters of total impaired and overdue

assets.

10. The banking sector is dominated by five registered banks. They hold nearly

90 percent of the sector’s assets and deposits (Table 4), and earn more than 80 percent of

industry profits. One of the five banks operates as a branch of an Australian parent, despite a

recently amended rule that is intended to require local incorporation for systemically

important banks. The other four banks are subsidiaries of Australian parent banks.

11. Banks are retail oriented, with mortgage lending amounting to nearly 60 percent

of the overall loan portfolio, and have only modest exposures to other sectors.

Agricultural loans are the second most important group, accounting for slightly more than

11 percent of lending. Lending for purposes other than property acquisition may be

understated in official statistics, as consumer and small business loans reportedly are often

secured by residential property. Given the high share of mortgages, recent increases in house

prices have given rise to concerns about a possible reversal of property prices. Banks have

argued that risk mitigating factors include the low average loan-to-value ratios of about

60 percent, conservative conditions on new lending (with most lending above a loan-to-value

ratio of 80 percent covered by mortgage insurance). Also, there is a substantial increase in

the demand for housing due to net immigration and cultural preference for home ownership.

Stress tests conducted as part of the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP)

(Section III) examine this issue further.

12. The banking system is funded to a large extent by domestic deposits. A

significant share of the country’s capital inflows are, however, borrowings undertaken by the

banking sector. About 30 percent of bank liabilities (nearly 50 percent of GDP) are owed to

nonresidents (Table 3). About half of the foreign liabilities of banks are to affiliates. About

one-third of banks’ foreign borrowing is denominated in NZDs, with the rest split between

Australian dollars, U.S. dollars, and other currencies, generally swapped back into NZDs.

Only a minor share of the foreign borrowing is on-lent in foreign currency.

Nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs)

13. The nonbank financial sector accounts for only a quarter of financial system

assets (Table 4). Among the different institutions, managed funds—superannuation funds,

unit trusts, and group funds—account for the largest share of system assets at 16 percent.

Insurance companies account for another five percent of assets, followed by finance

companies with three percent of assets. Building societies and credit unions are quite small,

with less than one percent of system assets.

14. The managed funds industry is the most important vehicle for investing

household funds outside of the banking system, accounting for $NZ 44 billion in assets

at end-2002. Almost two-thirds of managed funds are invested in unit trusts or group

investment funds. Two of the largest funds-management companies are owned by major

banks and two by large multinational insurance companies. Private superannuation funds are

- 13 -

also a significant component of the managed funds sector, accounting for $NZ 17 billion in

assets at end-2002. However, the removal of tax incentives has reduced the importance of

these funds as a vehicle for household savings. A new government-run New Zealand

Superannuation Fund was established in 2001 to partially pre-fund the public pension

system. At end-January 2004, it had about $NZ 3.1 billion in assets, and is expected to grow

by about $NZ 2 billion a year.

15. The insurance sector in New Zealand remains small relative to other countries.

Measured in premiums per capita, New Zealand ranks only twenty-eighth in the world. Life

insurance is dominated by a bank subsidiary and three subsidiaries of major foreign

insurance companies, but the remaining four large banks also have life insurance affiliates.

The life insurance sector has gradually declined in importance over the past five years, due to

competition from other products and institutions. In contrast, the nonlife sector has enjoyed

stable growth and now amounts to almost twice the life insurance market by premium

income. Two government-run agencies (the Accident Compensation Commission and the

Earthquake Commission) provide mandatory workers compensation/accident insurance and

earthquake insurance, respectively. These agencies held approximately $NZ 5.9 billion and

$NZ 4.1 billion in assets at end-June 2003.

16. Finance companies, building societies, and credit unions undertake bank-like

activities and finance themselves largely by deposit taking. Finance companies and

building societies have grown rapidly in the past five years, but remain small compared to the

major banks. Credit unions have declined in size and membership, holding less than one

percent of total financial system assets. Finance companies operate in areas not fully covered

by the major banks, including household lending (where finance companies provide over a

third of consumer credit); higher-risk property lending; and vehicle, plant, and machinery

leasing. Building societies concentrate on deposit taking and property lending only. The

largest finance company is a subsidiary of one of the major banks; most others are privately

held. The sector is profitable, with returns on equity above 20 percent for the sector as a

whole, and returns on assets of around 2 percent. Building societies, which are member-

owned, are also profitable but lag behind banks and finance companies, with returns on

equity averaging nine percent for the last three years and return on assets averaging about

0.75 percent.

Securities markets

17. New Zealand equity markets are comparatively small with market capitalization

of about 44 percent of GDP. Reflecting a preference for property investment, ownership of

New Zealand-listed equities remains mostly in the hands of offshore investors and domestic

institutional investors, with only about one-fourth held directly by households. Securities

market intermediaries include share brokers, futures dealers, investment advisers, and

managers of collective investment schemes (CIS). The New Zealand Stock Exchange (NZX)

is the country’s only registered securities exchange and was demutualized in December 2002.

Efforts are underway to increase access by small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs),

including the recent launch of a new market with listing standards tailored to SMEs. The

- 14 -

parent corporation of the New Zealand Futures and Options Exchange (NZFOE)—the only

futures and options exchange in the country—has announced that trading in NZFOE products

will be transferred to Australia in 2004.

C. Supervision and Regulation

18. New Zealand regulators do not carry any duty to protect individual depositors

or policyholders, or to safeguard individual institutions, unlike many other

jurisdictions. There is no official deposit protection or policyholder protection scheme. The

New Zealand supervisory and regulatory framework was introduced as a component of the

financial sector reforms initiated in the 1980s, while much of the current nonbank regulatory

framework, particularly in relation to securities markets, was established in the 1970s.

The banking sector

19. The current supervision framework is built around three main pillars: self

discipline, market discipline, and regulatory discipline. A cornerstone of the

self-discipline component is a requirement that directors attest quarterly that their bank’s

risk-management systems are adequate, and that they are being properly applied. This

procedure reinforces self discipline and reduces complacency by threatening civil and

criminal penalties in case of noncompliance and by exposing directors in the event of

misleading or adverse disclosures. Market discipline is promoted through the issuance of

quarterly disclosure statements on the bank’s financial condition, risk profiles, and risk-

management policies. Market discipline is reinforced by the absence of deposit insurance,

and a cultural ethos of “buyer beware.” The disclosure requirements and associated audit

requirements are meant to ensure that higher-quality data is provided to creditors and

investors on a more frequent basis than would otherwise be the norm. Finally, regulatory

discipline is enforced through the application of various prudential requirements by the

RBNZ, which is charged with licensing and supervising registered banks.

20. The RBNZ has a range of enforcement powers, and complements self- and

market discipline with off-site reviews and high-level discussions with banks. Activities

include regular RBNZ scrutiny of all quarterly disclosure statements, maintenance of active

working relationships with banks through annual consultation with senior management, as

well as through more informal contacts, regular meetings with other bank regulators and

credit-rating agencies, and annual meetings with the boards of the larger banks. However, the

RBNZ lacks a regular or targeted on-site supervision program, even though its Act does

provide the necessary powers to do so. Recent legislative changes have expanded the

RBNZ’s powers in certain areas, including a prior approval requirement for all significant

changes in bank ownership. The 2003 amendments to the RBNZ Act have also clarified and

expanded the Bank’s registration and enforcement powers and obligations.

21. The RBNZ achieved material compliance with most Basel Core Principles in the

assessment of observance, in spite of the special features of the regulatory framework.

Where differences exist, for example, in the monitoring of credit risks, these relate in some

- 15 -

cases to a conscious decision to leave oversight of such risks largely to the market. In other

cases, certain risks that are not supervised are not currently relevant to New Zealand.

22. A second layer of supervision is provided by the home-country supervision of all

the systemically important banks and their nonbank subsidiaries. The parent companies

of the local banks have generally imposed their own credit culture and risk-management

policies, systems, and procedures on their subsidiaries; such systems have already been

vetted by the home-country supervisor and are designed to meet its prudential requirements.

Home supervisors also conduct periodic on-site visits. The RBNZ has signed memoranda of

understanding with the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority and the U.K. Financial

Services Authority. The RBNZ maintains regular contact with foreign authorities, but does

not participate in on-site work nor does it receive supervisory reports sent to home-country

regulators.

Nonbank financial institutions and securities markets

23. Oversight of much of the nonbank sector and securities markets is indirect.

Reliance is placed upon a combination of market disclosure, rating agency assessments,

monitoring activities of self-regulatory organizations, trustees and auditors, and licensing and

registration requirements for certain categories of institutions.

24. For both the nonbank financial sector and securities markets, substantial

reliance is placed on self-regulatory organizations, trustees acting as private monitors,

and on the auditors of financial statements to ensure the provision of accurate

information. Additional oversight is provided by regulators outside of New Zealand for a

handful of the largest institutions (which account for over half the sector’s total assets),

because they are subsidiaries of large multinational banks or insurance companies. A large

number of NBFIs are not monitored by an overseas regulator or an exchange, since they are

domestically owned. While none of them is systemically important, the failure of any of the

larger nonbank institutions could nevertheless have a significant impact on market stability

through negative reputational effects on other institutions.

25. The Ministry of Economic Development (MED) is the main regulator of

nonbank institutions through its various business units, including the Registrar of

Companies and the Government Actuary. The MED has a role in ensuring compliance

with applicable laws for insurance companies, superannuation funds, building societies, and

credit unions, and to a more limited extent finance companies and managed funds. The legal

framework grants it some enforcement powers, including the ability to: (i) compel the entities

they regulate to provide additional information, as deemed necessary to facilitate oversight

and keep investors informed; (ii) appoint auditors; (iii) suspend registration; and (iv) place

companies in statutory management or liquidation. Despite these powers, ongoing oversight,

including review of periodic financial reports, is limited for some sections of the nonbank

sector.

- 16 -

26. For the securities sector, the principal regulator is the Securities Commission,

while the Takeovers Panel and Registrar of Companies have more narrowly defined

mandates. The principal elements of the securities regulatory framework are: initial and

ongoing disclosure requirements for public issuers, including collective investment schemes;

entry standards and oversight of some market intermediaries (principally exchange

members); supervision of most collective investment scheme operators by trustees and

private supervisors; regulation of takeovers; and certain restrictions on abusive conduct in

secondary markets. For securities markets, the NZX and the NZFOE establish and monitor

prudential standards and rules for the conduct of trading on the exchange, including

disclosure requirements. Most other market intermediaries, however, are subject to minimal

or no regulatory supervision. This includes, most notably, investment advisors.

27. The government, securities regulators, and NZX are taking steps to raise the

quality of securities regulation to high international standards. To date, the government

has provided sufficient funding to the Securities Commission and the Takeover Panel to

enable them to fulfill their responsibilities. Management of NZX is investing in its regulatory

functions and it cooperates with the Securities Commission and the Takeover Panel in

addressing regulatory concerns in areas of shared responsibility. Overall, the main

government regulatory agencies, MED, Securities Commission and the RBNZ, seem well

coordinated and maintain close contacts that enable them to monitor issues relating to cross-

linkages between NBFIs and banks. However, some gaps remain in the regulatory

framework. These gaps may make it more difficult for securities regulators to detect

incompetent or fraudulent conduct at an early stage and, in some instances, to take effective

enforcement action. The government and securities regulators are aware of these weaknesses,

are familiar with the relevant international best practices, and intend to carry out significant

reforms in the next few years.

28. New Zealand’s observance of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Principles

for Anti–Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) is

being assessed by a team from FATF and the Asia Pacific Group on Money Laundering

(APG). Field work has been completed, and the ROSC from the assessment will be

circulated to the Board once it is completed.

III. S

HORT-TERM STABILITY ISSUES

29. In all areas of short-term stress considered, the exposures of the New Zealand

financial system appear well-contained. Systems are in place to ensure an adequate

response if stresses were to occur.

A. Stress Testing the Financial System

30. In preparation for the FSAP, the RBNZ coordinated a stress-testing exercise

among the five systemically important banks. Stress tests were undertaken by banks and

results were aggregated by the RBNZ. The mission did not have access to individual bank

data.

- 17 -

31. The stress tests focused on risks judged relevant to the New Zealand market

(Table 5). Stress testing of the Australian parent groups of New Zealand banks was beyond

the scope of the New Zealand FSAP. Available data suggest that Australian banking groups

are profitable and well capitalized, with the New Zealand operations accounting (on average)

for less than twenty percent of group assets or profits. The mission reviewed the publicly

available reports on APRA’s stress tests of these groups, which focused on Australian

property price risks and found these risks to be manageable. Risks perceived most important

to New Zealand bank operations at this stage include significant changes in exchange rates,

New Zealand interest rates, property prices, and the price of agricultural output. The stress

test also included two dynamic macroeconomic scenarios, one based on the outbreak of foot-

and-mouth disease, a scenario that would lead to a significant shock to agricultural output

and far-reaching repercussions on the economy at large. A second scenario simulated a sharp

increase in the cost of foreign funding for New Zealand banks.

32. The results show a high degree of resilience of the banking system. Market-risk

shocks applied to bank trading books (which were large shocks compared to historical

experience) produced only small losses, given the small size of the bank’s trading book

(Table 6). A maximum loss for one bank of less than 15 percent of pre-tax profits emerges if

nominal New Zealand interest rates were to increase by 300 basis points, and bank positions

were all fixed at their most disadvantageous internal risk management limit. Results of the

credit-risk scenario, involving a 20 percent decline in property prices and some decline in

household income, would differ depending on, among other factors, portfolio concentration

on commercial property. The worst individual bank loss estimate would be below half of the

bank’s March 2003 annual pre-tax profits. These results are, in part, due to the characteristics

of bank mortgage portfolios in New Zealand, including a 60 percent average loan-to-value

ratio, and several contract features that allow homeowners to remain current on their loans

while facing temporary unemployment and reductions in income.

33. Results of the foot-and-mouth scenario suggest it would not pose a risk to the

solvency of the major banks. The dynamic scenarios are based on macroeconomic

assumptions provided by the RBNZ (Table 8). Results of these dynamic stress tests are

summarized in Figures 1 and 2. For the foot-and-mouth scenario, such a shock would impose

a modest but long-lasting drag on the profitability of systemically important banks. These

banks’ direct exposures to the agricultural sector are contained, and the exchange rate

depreciation associated with the scenario bolsters the profitability of other export industries.

In mission discussions, banks offered the opinion that the stress scenario assumptions were

perhaps too optimistic, and that a serious outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease might have

more wide-ranging effects than anticipated in the RBNZ simulations.

- 18 -

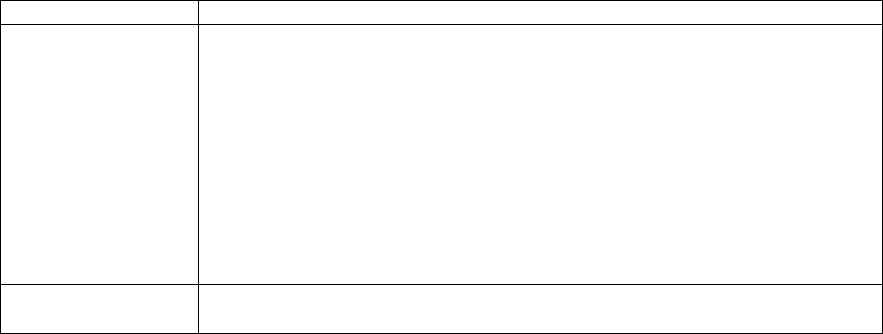

Table 5. Sensitivity Stress-Test Scenarios

Market-Risk Scenarios

Scenario Exchange Rates

1 30 percent depreciation of the New Zealand dollar relative to all other currencies

2 30 percent appreciation of the New Zealand dollar relative to all other currencies

Interest Rates

3 300 basis point increase in interest rates across the NZ yield curve

4

300 basis point increase in the long end (5+ years) of the NZ yield curve, short rates

unchanged

Credit-Risk Scenarios

Scenario Commodity Prices

1 A decline in the dairy payout to $2.50/kg for two consecutive years

Property prices and economic weakness

2

20 percent decline in residential property prices, with unemployment rising from 5

to 9 percent, and households’ real disposable income falling by 4 percent

3 20 percent fall in commercial property prices, 20 percent fall in corporate earnings

Source: RBNZ.

Table 6. Market Risk Results

1/

Shock

Average Loss as a

Percent of 2003

Profits 2/

Largest Individual Bank

Maximum Risk Loss as a

Percent of 2003 Profits

2/

Assuming Typical Bank Exposure

1 1.98 2.75

2 -1.00 0.39

3 2.75 3.82

4 0.43 0.91

Assuming Worst Case Exposures

1 3.80 8.60

2 -0.70 2.80

3 6.20 14.40

4 3.60 7.10

Source: RBNZ.

1/ Negative numbers represent gains.

2/ Actual reported annual pre-tax profit for the 12-month period ending in

March 2003.

- 19 -

Table 7. Credit Risk Results

Year

Average Cumulative

Loss as a Percent of

2003 Profits

1/

Largest Individual Bank

Loss as a Percent of

2003 Profits

1/

Credit Shock 1

1 3.09 8.33

2 4.35 11.38

Credit Shock 2

1 8.31 15.84

2 18.78 32.56

3 28.39 44.11

Credit Shock 3

1 1.90 3.46

2 6.63 10.79

3 9.76 19.50

Source: RBNZ.

1/ Actual reported annual pre-tax profit for the 12-month period ending in

March 2003.

Table 8. Model Assumptions

Foot-and-Mouth Disease Scenario Assumptions

80 percent decline in meat exports

20 percent depreciation of the New Zealand dollar against all other currencies

50 basis point increase in the risk premium for New Zealand dollar denominated

assets

A decline in the long-term capital/output ratio and net foreign assets.

Increase in Offshore Funding Costs

A depreciation of the New Zealand dollar by 40 percent

An increase of short- and long-term interest rates to 18–20 percent

A permanent increase in the risk premium on New Zealand dollar-denominated

assets

Source: RBNZ.

34. The results of the funding-costs-stress scenario show greater potential for loss.

Bank profitability falls in the early quarters of this scenario as market risk and banking book

losses are generated from a rise in interest rates and the sharp depreciation of the NZD.

Eventually, higher interest rates generate greater interest revenues as credits mature and are

- 20 -

repriced, but the rate rise and the weak economy cause a rise in residential mortgage defaults,

particularly on mortgages associated with investment properties. Lending to commercial

property developers is also expected to generate losses, yet the losses to the banking sector

will be attenuated by the losses that will be absorbed by mezzanine creditors, primarily

finance companies and contributory mortgage companies. While banks suffer depressed

profits, the results do not suggest that any bank’s capital position would be endangered by

this scenario.

Figure 1. Foot and Mouth Disease Scenario

Figure 2. Funding Shock Stress Scenario

B. Nonbank Financial Institutions

35. The NBFIs are small in comparison to the banking system, but are able to offer a

wide range of financial products similar to those offered by banks. NBFIs are subject to

prospectus and investment statement requirements under the Securities Act. However, NBFIs

are not subject to quarterly disclosure and directors’ attestations as required of banks. As a

result, there is little timely quantitative information that is readily available to depositors and

market participants. Most NBFIs are only required to report their financial results on an

annual basis, and often with a substantial reporting lag, although additional disclosures are

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1.1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 101112131415

Stress Quarter

Proportion of baseline profits_

sample average

lower envelope

Source: RBNZ.

-2.5

-2.0

-1.5

-1.0

-0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

123456789101112131415

Stress Quarter

Proportion of baseline profits_

sample average

lower envelope

Source: RBNZ.

- 21 -

required if there have been material adverse developments since the date of the most recent

prospectus. Furthermore, the government entity largely responsible for collecting this

information, the MED, has only limited capacity to compile and aggregate the relevant data.

36. The main NBFIs are affiliates of the major banks or multinational financial

groups and benefit, to some extent, from the regulation imposed on their parents.

However, the lack of timely and comprehensive disclosure of individual and aggregate data

for the sector potentially reduces the effectiveness of market discipline. It may also hamper

effective early intervention, should significant problems in the sector develop which, given

ownership links and similar business practices, have the potential for direct or indirect

spillover effects on banks. Efforts to coordinate and strengthen data collection and disclosure

would help regulators, market participants, and depositors to have a more accurate and timely

picture of developments in the sector.

C. Foreign Currency Exposure and Functioning of Exchange Markets

37. The stability of the financial system could be sensitive to a number of foreign-

exchange-related issues, due to high dependence on international trade and capital

flows. These include the management of exchange rate risk, access to overseas funding, and

the liquidity of the foreign exchange market. Appropriate risk management and well

functioning markets indicate, however, that short-term risks related to foreign exchange at

this time seem contained.

Foreign currency exposure

38. Exchange rate risk in New Zealand is well understood and managed actively by

banks and other market participants. Markets have coped successfully with considerable

volatility in the exchange rate. From January 1997 to November 2000, the New Zealand

dollar depreciated by about 45 percent against the U.S. dollar, and it subsequently

appreciated by 73 percent by February 2004. As a result, banks require the adoption of

hedging policies when considering applications for loans by corporations. A very high

percentage of foreign-currency-denominated overseas debt is hedged: over 96 percent in the

banking sector and 78 percent in other sectors, thus greatly reducing balance sheet risks.

Approximately 70 percent of the hedging is done using financial contracts with the remainder

naturally hedged against foreign exchange assets or receipts. Operational foreign exchange

risk is also very conservatively managed with large exporters consistently hedging

receivables and forecasting receipts over their planning horizon. The public sector has no net

foreign-exchange-denominated debt.

39. There is little evidence of major residual NZD exchange rate risk remaining for

the country. Exchange rate risk is frequently intermediated separately from the credit risk

(via the derivative markets) and often passes through a number of intermediaries, with

market participants themselves unaware of the end-recipient. New Zealand institutions and

statistical services do not attempt to identify market participants in any systematic fashion,

and thus it is difficult to determine the ultimate bearer of NZD risk. However, the following

- 22 -

factors seem to mitigate any possible risk for New Zealand: (i) counterparties to hedges seem

to be varied, but all of them are nondomestic entities, including foreign households and retail

investors, overseas insurance companies and fund managers, and international currency

overlay investors and hedge funds; (ii) market participants appear to be widely dispersed

geographically and are relatively numerous, so the risk is not overly concentrated in one

country or type of investor; and (iii) the demand for New Zealand dollar risk appears to be

fairly steady over time, as evidenced by the ability to hedge New Zealand currency risk

consistently over time and in a large variety of market conditions, and the fact that almost

half of New Zealand’s international financial liabilities are denominated in domestic

currency.

Foreign exchange market

40. The foreign exchange market in New Zealand functions efficiently and provides

a reasonable degree of liquidity, commensurate with the size of the New Zealand

economy. Seven banks are currently market makers in the NZD, and most trading now takes

place outside of New Zealand—primarily in Australia, but also in London and New York. In

April 2001, average daily trading volume in Australia and New Zealand was approximately

$NZ 2.8 billion in the spot market and $NZ 13 billion in the swap market. There are

indications that trading volumes have declined, possibly substantially, since then. Trading

spreads are similar to those of other comparable currencies. Settlement risk is present but will

be greatly reduced when the New Zealand dollar becomes eligible for inclusion in the

Continuous Linked Settlement (CLS) Bank, currently expected by end-2004.

41. The RBNZ maintains limited liquid reserves (approximately $NZ 4.3 billion)

and the technical capability to intervene in foreign exchange markets, although it has

not intervened since 1985. This framework provides a limited safety net, as it would allow

the bank to intervene in order to restore liquidity to a severely disrupted FX market, reducing

possible systemic risks for the New Zealand economy. The RBNZ has recently

recommended to the Minister of Finance that the RBNZ, as one of its policy implementation

tools, should have the capacity to intervene to influence the level of the exchange rate when

the rate was “exceptionally and unjustifiably” high or low.

D. Money and Bond Markets

42. The money market in New Zealand consists of a range of short-term debt

instruments, including treasury bills, bank bills, and commercial paper, together with a

variety of derivative financial instruments, such as bank bill futures, interest rate swaps

and options, and forward-rate agreements. Secondary markets for most instruments exist,

with the market for bank bills and their futures being the most liquid. The secondary market

for treasury bills and commercial paper is much less liquid because investors tend to hold

these instruments until maturity. Trading activity is dominated by five or six of the major

banks and three brokers.

- 23 -

43. New Zealand bond markets are dominated by government bonds, with around

$NZ 21.8 billion outstanding. Government bonds are the most liquid instrument, with daily

turnover in the secondary market around $NZ 3 billion, mostly in repo transactions. The

bonds are issued through the New Zealand Debt Management Office, a branch of the New

Zealand Treasury, with the RBNZ acting as agent. There are about 10 active bidders in the

regular tenders, held approximately 12 times a year. In the secondary market, there are seven

price makers and three active brokers. The larger corporates, banks, and state-owned

enterprises with investment-grade credit ratings issue corporate bonds, mostly by tender or

private placement. At present, there are around $NZ 7.2 billion outstanding for

approximately 30 issuers, mostly with maturities of three to seven years. Most issues are

illiquid. There is also a relatively large market in Eurokiwi bonds (presently around

$NZ 11.9 billion outstanding), which are denominated in NZD and offered by offshore

entities to investors outside of New Zealand.

E. Systemic Liquidity Provision

44. The RBNZ is actively involved in liquidity management through its daily open

market operations (OMO), including foreign exchange swaps. It also has a range of

standing facilities, in the context of the overnight interest rate target (the Official Cash Rate

or OCR). The interbank market for overnight funds appears to function well, with most banks

able to meet their liquidity needs either from other market participants through secured and

unsecured lending or from the daily injection of funds through OMO. Market frictions

occasionally occur when there are imbalances in holdings of government bonds (such as one

bank accumulating a large position in cash or government securities). In these circumstances,

banks prefer to pay a penalty rate (of 25 or 30 basis points above the OCR) to the RBNZ for

the use of its standing facilities. This is in preference to paying banks holding surplus

liquidity a rate at or above the OCR when secured with government securities, and depart

from the market convention of settling transactions at the OCR rate. The repeated nature of

transactions in a small market with a limited number of players seems to promote the

maintenance of this convention.

45. The RBNZ appears to have sufficient information to be able to detect and

respond to any short-term liquidity difficulties should they arise. The RBNZ has frequent

contact throughout the day with market participants and collects information on a daily basis

on interbank lending positions. The RBNZ also monitors transactions in the payment system

for signs of settlement difficulties.

2

However, the fact that the market does not always clear

because of stickiness in the price raises issues about how the market might react to

disruptions in interbank markets. The standing facilities in place provide a convenient

mechanism for banks to acquire liquidity from the central bank in the event of market

2

The mission did not undertake an assessment of the payment system. The RBNZ did

provide a detailed self-assessment of the Core Principles for Systemically Important Payment

Systems, which did not indicate any major deficiencies.

- 24 -

frictions. The RBNZ has adequate powers under the Reserve Bank Act to provide lender-of-

last-resort (LoLR) facilities, but since the revision of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act

in 1989, the RBNZ has not provided emergency liquidity support to any institution. The

RBNZ is presently reviewing its internal policies relating to LoLR facilities in connection

with efforts to formalize crisis management approaches.

IV. MEDIUM-TERM AND STRUCTURAL ISSUES

46. The ongoing changes in the financial sector landscape and ownership patterns

imply a need to reinvigorate the regulatory and operating framework to keep it up-to-

date. Adaptations may be called for in several areas. First, the regulatory approach may leave

the RBNZ and other regulators at times without the optimal level of information to make

informed judgments about systemic issues. Second, there are open questions regarding how a

financial crisis might be addressed. Finally, increased financial interdependence with

Australia and other financial centers may need to be more explicitly acknowledged in the

formulation of the regulatory framework.

A. Banking Supervision

47. New Zealand led the way in disclosure when it was first introduced, and it

achieved a high degree of financial sector stability within this framework. Since that

time, international best practices for disclosure have evolved and, in some instances, have

surpassed practices in New Zealand. Disclosure remains a valuable discipline on banks, and

New Zealand’s banking system is more transparent than many others. However, the

information disclosed in the quarterly statements could be enhanced to provide more

effective market discipline. Disclosure statements do not appear to be widely used at the

retail level, and are not sufficiently comprehensive or timely to be used by wholesale

counterparties for assessing creditworthiness, nor for some supervisory judgments. It would,

therefore, be appropriate to review the contents of the statements and supplement them with

focused, prudential information directly for the supervisor. The RBNZ might benefit from

having its own set of early-warning indicators, which should include, inter alia, information

on individual bank liquidity and large exposures.

48. There are almost no independent supervisory checks on banks’ systems and

controls, aside from external auditors’ checks. This reflects the current regulatory

philosophy, but such checks need not be overly intrusive, if properly focused. They can also

add value, both in identifying incipient weaknesses in individual banks and by enabling the

RBNZ to draw best-practice lessons for the banking system as a whole. The RBNZ might

consider commissioning third-party reports and establishing a small, specialist team in-house

to make focused, on-site visits on particular aspects of credit and operational risk.

49. Directors play a critical part in the New Zealand approach to banking

supervision. It is therefore important that the fit-and-proper criteria be kept under review and

the vetting process be sufficiently thorough. The role is demanding, and independent

- 25 -

directors might benefit from more regular communication with the RBNZ, perhaps at an

annual meeting to review developments and any issues they might have.

B. Crisis Management

50. New Zealand’s regulatory philosophy and the absence of depositor protection, in

conjunction with the almost fully foreign-owned banking system, would pose particular

challenges if a banking crisis were to emerge. Key concerns for crisis resolution include:

(i) the ability of the RBNZ to act as an LoLR; (ii) foreign bank branches being systemically

important; and (iii) subsidiaries of foreign banks, while having legal standing, being unable

to be economically viable on their own.

Lender-of-last-resort powers

51. Under the Reserve Bank Act, the RBNZ is required to act as an LoLR when

needed to ensure the soundness of the financial system. In formulating its LoLR policies,

the RBNZ has specified that it would only provide credit to an institution whose solvency is

not in material doubt, after the institution had fully exhausted market sources of liquidity, and

where it is necessary to maintain the stability of the financial system.

52. The RBNZ’s monitoring may not provide sufficient information at the onset of a

sudden crisis situation. The information that would be used by the RBNZ to independently

determine an institution’s eligibility for LoLR operations have not been formally articulated.

The RBNZ may not have access to sufficiently timely and detailed supervisory data that

could be utilized to make a speedy judgment about an institution’s solvency. The RBNZ can

request further information from a bank under Section 93, but a response may take

significant time. The present LoLR system relies heavily on directors’ or parent-banks’

attestations as to the solvency of a New Zealand bank operation. The RBNZ may wish to

consider again whether additional or more timely information might help it reach a better

judgment on solvency in a crisis situation.

Problem bank resolution policies

53. The RBNZ approach to banking supervision and the dominance of foreign

institutions in the financial system may complicate bank resolution, especially in the

case of systemically important institutions. The “hands-off” supervisory approach and

reliance on disclosure requirements may delay detection of emerging problems, thus

lengthening supervisory response time in a crisis. Furthermore, the range of remedial actions

that the RBNZ can take in response to a bank in difficulties is complicated for foreign

branches by legal uncertainties surrounding which assets and liabilities would be subject to

statutory management control. For a foreign-owned subsidiary, the dependence on the parent

bank can present difficulties in determining the true condition of the bank, and could also

give rise to cross-jurisdictional issues and other delays. These issues are particularly acute for

New Zealand, because all of the systemically important banks are foreign-owned.

- 26 -

54. To enhance financial stability, the RBNZ has been reviewing a range of

alternative policy options, including a specific open-bank resolution policy based on

recapitalization by creditors. The RBNZ has been conducting feasibility studies and is

attempting to clarify IT-related and other issues, with a view to making it operational. The

options to effect a bank resolution could include other alternatives such as a government bail-

out, a recapitalization with loss sharing between the government and depositors, orderly

liquidation, or a “lifeboat” rescue by the banking industry. The RBNZ’s bank resolution

policies are not yet fully defined and warrant further assessment, in the context of the overall

range of options available to address bank failures and resolution.

C. Cooperation with Australia

55. The recent increase in Australian ownership of banking assets has raised the

awareness of the high degree of interdependence between New Zealand and Australia’s

banking systems. Specific concerns about this interdependence include: (i) loss of control

over systems and functions; (ii) effects of Australian depositor protection on New Zealand

depositors; and (iii) regulatory harmonization between both countries. All issues are under

review by the RBNZ and are actively discussed with Australian counterparts; however, the

dialogue may need to be intensified to achieve satisfactory progress in a reasonable time

frame. In parallel with these discussions, the RBNZ is working on stand-alone policies

regarding local incorporation, director attestations, and outsourcing, in recognition of the

need for more immediate responses to certain developments.

56. Closer integration of foreign-owned banks and other financial institutions has

led to increasing outsourcing of IT and management functions to parent companies.

3

Such outsourcing has been driven by efficiency considerations and occurred both in

subsidiaries and in branches of foreign banks. The RBNZ estimates that at least half of the

banks operating in New Zealand are no longer operating as separable entities, given that

account and back-up information may not be readily available on site in New Zealand or in

an accessible back-up site. While this will not be a concern in normal times, it will be a

serious impediment to the RBNZ’s actions in case of a systemic crisis.

57. To avoid further “hollowing out” of core functionality, the RBNZ is working

with banks on assessing where core functions are being located. It plans to use the

conditions of registration to ensure that necessary management skills and back-up sites are

available in New Zealand. Preliminary discussions of the issue have taken place with the

Australian regulators, but further contact and a coordinated response to “third-party

outsourcing” might be necessary. The RBNZ might also want to consider increasing its

systematic knowledge about the core functionality of the New Zealand banks through a

targeted audit of banks.

3

Parent companies themselves have also outsourced some services, possibly beyond the full

reach of the home-country regulator.

- 27 -

58. A second concern for the New Zealand authorities relates to the possible effects

of the Australian depositor-preference scheme and its possible negative effects on New

Zealand depositors in case of a crisis. The Australian depositor-preference scheme

prescribes priority of Australian depositors over assets in Australia in the case of a bank

resolution. The issue is of particular concern in the case of one systemically important bank

operating as a branch of an Australian bank, as the parent bank may be able to shift assets

easily to Australia. However, there are also concerns that interbank-lending operations might

make it possible for banks operating as subsidiaries to concentrate assets in the home country

to the detriment of New Zealand depositors. The connected lending limits imposed by the

RBNZ may reduce the risks associated with asset shifting, and the RBNZ is also discussing

the issue with the Australian authorities, but the issue remains.

59. Banks in New Zealand are effectively subject to home- and host-country

regulations. Given the more “hands-on” approach pursued by the Australian regulators, the

additional compliance requirement for New Zealand banks arises mainly in the preparation of

quarterly rather than six-monthly disclosure statements. There are also some differences in

capital adequacy requirements, and the RBNZ also imposes additional requirements

concerning connected lending limits. Going forward, though, as the regulatory regime

changes, issues could arise; for example, with regard to Basel II where New Zealand plans to

implement the standardized approach and Australia plans to adopt the internal ratings-based

approach. The extent and possible implications of such reforms should be discussed among

regulators before a final decision on new regulation is made.

- 28 - ANNEX

OBSERVANCE OF STANDARDS AND CODES—SUMMARY ASSESSMENTS