1

Medical Policy

Joint Medical Policies are a source for BCBSM and BCN medical policy information only. These documents

are not to be used to determine benefits or reimbursement. Please reference the appropriate certificate or

contract for benefit information. This policy may be updated and is therefore subject to change.

*Current Policy Effective Date: 5/1/24

(See policy history boxes for previous effective dates)

Title:

Dry Needling of Trigger Points for Myofascial Pain

Description/Background

Dry Needling

Dry needling refers to a procedure in which a fine needle is inserted into the skin and muscle at

a site of myofascial pain. The needle may be moved in an up-and-down motion, rotated, and/or

left in place for as long as 30 minutes. The intent is to stimulate underlying myofascial trigger

points, muscles, and connective tissues to manage myofascial pain. Dry needling may be

performed with acupuncture needles or standard hypodermic needles but is performed without

the injection of medications (e.g., anesthetics, corticosteroids). Dry needling is proposed to treat

dysfunctions in skeletal muscle, fascia, and connective tissue; diminish persistent peripheral

pain, and reduce impairments of body structure and function.

The physiologic basis for dry needling depends on the targeted tissue and treatment objectives.

The most studied targets are trigger points. Trigger points are discrete, focal, hyperirritable

spots within a taut band of skeletal muscle fibers that produce local and/or referred pain when

stimulated. Trigger points are associated with local ischemia and hypoxia, a significantly

lowered pH, local and referred pain and altered muscle activation patterns.

1

Trigger points can

be visualized by magnetic resonance imaging and elastography. The reliability of manual

identification of trigger points has not been established.

Deep dry needling is believed to inactivate trigger points by eliciting contraction and subsequent

relaxation of the taut band via a spinal cord reflex. This local twitch response is defined as a

transient visible or palpable contraction or dimpling of the muscle, and has been associated

with alleviation of spontaneous electrical activity; reduction of numerous nociceptive,

inflammatory, and immune system related chemicals; and relaxation of the taut band.

1

Deep dry

needling of trigger points is believed to reduce local and referred pain, improve range of motion,

and decrease trigger point irritability.

2

Superficial dry needling is thought to activate mechanoreceptors and have an indirect effect on

pain by inhibiting C-fiber pain impulses. The physiologic basis for dry needling treatment of

excessive muscle tension, scar tissue, fascia, and connective tissues is not as well described in

the literature.

1

Regulatory Status

Dry needling is considered a procedure and, as such, is not subject to regulation by the U.S.

Food and Drug Administration.

Medical Policy Statement

Dry needling of myofascial trigger points is experimental/investigational. It has not been

scientifically demonstrated to improve patient clinical outcomes.

Inclusionary and Exclusionary Guidelines

N/A

CPT/HCPCS Level II Codes (Note: The inclusion of a code in this list is not a guarantee of

coverage. Please refer to the medical policy statement to determine the status of a given procedure.)

Established codes:

N/A

Other codes (investigational, not medically necessary, etc.):

20560 20561 20999

Note: Codes 97810-97814 are not appropriate since this is not the same as acupuncture

Note: Individual policy criteria determine the coverage status of the CPT/HCPCS code(s) on this

policy. Codes listed in this policy may have different coverage positions (such as established or

experimental/investigational) in other medical policies.

Rationale

Evidence reviews assess the clinical evidence to determine whether the use of technology

improves the net health outcome. Broadly defined, health outcomes are the length of life,

quality of life (QOL), and ability to function-including benefits and harms. Every clinical

condition has specific outcomes that are important to patients and managing the course of that

condition. Validated outcome measures are necessary to ascertain whether a condition

improves or worsens; and whether the magnitude of that change is clinically significant. The

net health outcome is a balance of benefits and harms.

3

To assess whether the evidence is sufficient to draw conclusions about the net health outcome

of technology, two domains are examined: the relevance, and quality and credibility. To be

relevant, studies must represent one or more intended clinical use of the technology in the

intended population and compare an effective and appropriate alternative at a comparable

intensity. For some conditions, the alternative will be supportive care or surveillance. The

quality and credibility of the evidence depend on study design and conduct, minimizing bias

and confounding that can generate incorrect findings. The randomized controlled trial (RCT) is

preferred to assess efficacy; however, in some circumstances, nonrandomized studies may be

adequate. RCTs are rarely large enough or long enough to capture less common adverse

events and long-term effects. Other types of studies can be used for these purposes and to

assess generalizability to broader clinical populations and settings of clinical practice.

Dry Needling of Trigger Points Associated with Neck and/or Shoulder Pain

Clinical Context and Therapy Purpose

The purpose of dry needling in patients who have myofascial neck and/or shoulder pain is to

provide a treatment option that is an alternative to or an improvement on existing therapies.

The following PICO was used to select literature to inform this review.

Populations

The relevant population of interest are individuals with myofascial trigger points associated

with neck, shoulder pain. Trigger points are discrete, focal, hyperirritable spots within a taut

band of skeletal muscle fibers that produce local and/or referred pain when stimulated.

Interventions

The therapy being considered is dry needling.

Dry needling refers to a procedure whereby a fine needle is inserted into the trigger point to

induce a twitch response and relieve the pain. The needle may be moved in an up-and-down

motion, rotated, and/or left in place for as long as 30 minutes. The physiologic basis for dry

needling depends on the targeted tissue and treatment objectives. Deep dry needling is

believed to inactivate trigger points by eliciting contraction and subsequent relaxation of the

taut band via a spinal cord reflex. Superficial dry needling is thought to activate

mechanoreceptors and have an indirect effect on pain by inhibiting C-fiber pain impulses.

Comparators

Alternative nonpharmacologic treatment modalities for trigger point pain include manual

techniques, massage, acupressure, ultrasonography, application of heat or ice, diathermy,

transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and spray cooling with manual stretch.

2

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest are symptoms, functional outcomes, QOL, and treatment-related

morbidity.

4

Review of Evidence

Systemic Reviews

Numerous, primarily small, RCTs involving dry needling techniques in neck or shoulder pain

have been evaluated in several systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Charles et al (2019) conducted a systematic review of different techniques for treatment of

myofascial pain.

3

A total of 23 studies of dry needling were included. Of these, 15 assessed

the technique for neck or shoulder pain. The quality of evidence for dry needling in the

management of myofascial pain and trigger points ranged from very low to moderate

compared with control groups, sham interventions, or other treatments for changes in pain,

pressure point threshold, and functional outcomes. Multiple limitations in the body of the

evidence were identified, including high risk of bias, small sample sizes, unclear randomization

and concealment procedures, inappropriate blinding, imbalanced baseline characteristics, lack

of standardized methodologies, unreliable outcome measures, high attrition rates, unknown

long-term treatment effects, lack of effective sham methods, and lack of standardized

guidelines in the location of trigger points. The reviewers concluded that the evidence for dry

needling was not greater than placebo.

Navarro-Santana et al (2020) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of dry

needling of myofascial trigger points associated with neck pain compared to sham needling, no

intervention, or other physical interventions.

4

A total of28 RCTs were included. Dry needling

reduced pain immediately after the intervention (mean difference [MD] in pain score-1.53; 95%

confidence interval [CI] -2.29 to -0.76) and at the short-term (up to 1 month) (MD -2.31, 95% CI

-3.64 to -0.99)when compared with sham, placebo, waiting list, or other forms of dry needling,

and at the short-term compared with manual therapy (MD -0.51, 95% CI -0.95 to -0.06). No

differences in comparison with other physical therapy interventions were observed. An effect

on pain-related disability at the short-term was found when comparing dry needling with sham,

placebo, waiting list, or other form of dry needling, but not with manual therapy or other

physical therapy interventions.

Navarro-Santana et al (2020) also conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of dry

needling for shoulder pain.

5

The meta-analysis found moderate quality evidence for a small

effect (MD -0.49 points; 95% CI -0.84 to -0.13;standardized mean difference [SMD] -0.25; 95%

CI -0.42 to -0.09) for decreasing shoulder pain intensity, and low quality evidence for a large

effect (MD -9.99 points; 95% CI -15.97 to -4.01; SMD -1.14; 95% CI -1.81 to -0.47) for

reducing related disability. The effects on pain intensity were found only in the short term (up to

1 month) and did not reach the minimal clinically important difference of 1.1 points for the

numerical pain rating scale (0 to 10) determined for patients with shoulder pain. Confidence

intervals of the main effects of dry needling on pain intensity and related disability were wide.

Additionally, the trials were heterogeneous with regard to the number and/or frequency of

needling sessions and the type of comparator.

Para-Garcia et al (2022) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of dry-needling

compared with other interventions in patients with subacromial pain syndrome.

16

Five RCTs

(N=315) published between 2012 and 2022 were included. The intervention group included 3

studies with dry needling in combination with exercise and 2 studies with dry needling alone

while the control group had a wide range of interventions including exercise, stretching,

massage, heat, and electrotherapy. Dry needling was generally performed for 2 sessions over

5

3 or 4 weeks, but 1 study had all sessions in 1 week. Minimal information was available on

session duration. Short-term pain was reduced with dry needling either alone or when

combined with exercise compared with other interventions (SMD, -0.27; 95% CI, -0.49 to -0.05;

I2=0.00%; p<.02; low quality evidence), but the difference between groups was small and

clinical relevance is questionable. Pain intensity was also reduced at mid-term (1 to 12

months) based on low-quality evidence; however, there was no difference in disability between

groups. The quality of evidence was low to very-low due to lack of blinding and imprecision.

Section Summary: Neck and/or Shoulder Pain

A number of RCTs and systematic reviews of these studies have evaluated dry needling of

myofascial trigger points for neck and/or shoulder pain. A systematic review of techniques for

myofascial pain included 15 studies of dry needling for neck or shoulder pain published

through 2017. Studies had multiple methodological limitations, and the reviewers concluded

that the evidence for dry needling was not greater than placebo. In more recent systematic

reviews and meta-analyses, dry needling was not associated with clinically important

reductions in shoulder or neck pain when compared toother physical therapy modalities.

Dry Needling of Myofascial Trigger Points Associated with Plantar Heel Pain

Review of Evidence

Systemic Review

Llurda-Almuzara et al (2021) published a systematic review of 6 randomized trials (N=395)

evaluating dry needling for the treatment of plantar fasciitis (Tables 1 to 3).

6,

None of the

included trials were double-blind and, although the authors did find some positive effects of dry

needling, the heterogeneity, lack of blinding, and small number of patients in the trials limits

applicability.

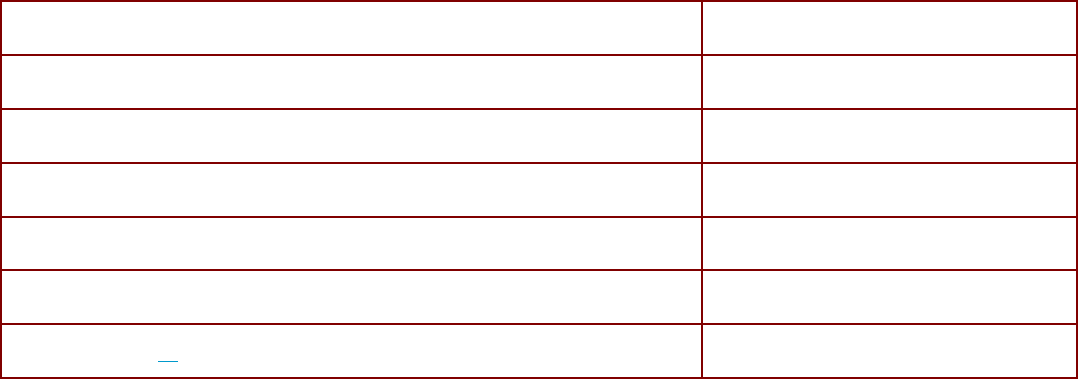

Table 1. Trials Included in Systematic Review

Study

Llurda-Almuzara et al (2021)

6,

Bagcier et al (2020)

7,

⚫

Cotchett et al (2014)

8,

⚫

Eftekharsadat et al (2016)

9,

⚫

Rahbar et al (2018)

10,

⚫

Rastegar et al (2017)

11,

⚫

Uygur et al (2019)

12,

⚫

6

Table 2. Systematic Review Characteristics

Study

Dates

Trials

Participants

N (Range)

Design

Duration

Llurda-

Almuzara

et

al (2021)

6,

Inception-

2020

6

Patients with heel pain

receiving dry needling

or comparator (placebo,

no intervention, or active

comparator)

395 (10 to

49)

RCT

1 to 6 sessions (mean,

4 sessions)

RCT: randomized controlled trial.

Table 3. Systematic Review Results

Study

Overall

Pain

Intensity

Pain Intensity

(at least 3 Sessions)

Long-term Pain Intensity

Pain-related Disability

Llurda-Almuzara et al (2021)

6,

Trials (n)

6

4

2

5

SMD (95% CI)

-0.5 (-1.13 to

0.13)

-1.28 (-2.11 to -0.44)

-1.45 (-2.19 to -0.70)

-0.46 (-0.90 to -0.01)

I

2

94%

>85%

67% to 78%

84%

CI: confidence interval; SMD: standardized mean difference.

Section Summary: Plantar Heel Pain

The evidence base consists of a systematic review of RCTs. The authors included 6

randomized trials enrolling 395 patients and found no overall difference in pain intensity in

those treated with dry needling compared with active control, placebo, or no intervention.

However, pain intensity after at least 3 sessions, long-term pain intensity, and pain-related

disability were improved. The systematic review rated the quality of the studies it assessed as

low to moderate. The evidence is limited by small patient populations and lack of blinding;

therefore, additional RCTs are needed to strengthen the evidence base.

Dry Needling of Myofascial Trigger Points Associated with Temporomandibular Pain

Review of Evidence

Randomized Controlled Trials

A double-blind, sham-controlled trial of dry needling for the treatment of temporomandibular

myofascial pain was reported by Diracoglu et al (2012).

13

Patients (N=52) with symptoms for at

least 6 weeks with 2 or more myofascial trigger points in the temporomandibular muscles were

included in the trial. Trigger points were stimulated once weekly over three weeks. The sham

condition involved dry needling in areas away from the trigger points. Patients were evaluated

one week after the last needling. At follow-up, there was no significant difference between

groups in pain scores assessed by a 10-point VAS. Mean VAS scores were 3.88 in the

treatment group and 3.80 in the control group (p=.478). Also, the difference in unassisted jaw

opening without pain did not differ significantly between the treatment group (40.1 mm) and the

7

control group (39.6 mm; p=.411). The mean pain pressure threshold was significantly higher in

the treatment group (3.21 kg/cm

2

) than in the control group (2.75 kg/cm

2

; p<.001).

Section Summary: Temporomandibular Myofascial Pain

One RCT evaluating dry needling for the treatment of temporomandibular myofascial pain was

identified; this trial was double-blind and sham-controlled. One week after completing the

intervention, there were no statistically significant differences between groups in pain scores or

function (unassisted jaw opening without pain). There was a significantly higher pain pressure

threshold in the treatment group. This single RCT does not provide sufficient evidence on

which to draw conclusions about the impact of dry needling on health outcomes in patients

with temporomandibular myofascial pain.

Adverse Events

A prospective survey (2014) of 39 physical therapists, providing 7629 dry needling treatments,

reported 1463 (19.18%) mild adverse events (bruising, bleeding, pain) and no serious adverse

events.

14

Summary of Evidence

For individuals who have myofascial trigger points associated with neck and/or shoulder pain

who receive dry needling of trigger points, the evidence includes randomized controlled trials

(RCTs) and systematic reviews. The relevant outcomes are symptoms, functional outcomes,

QOL, and treatment-related morbidity. A systematic review of techniques to treat myofascial

pain included 15 studies of dry needling for neck or shoulder pain published through 2017.

Studies had multiple methodological limitations, and the reviewers concluded that the evidence

for dry needling was not greater than placebo. In more recent systematic reviews and meta-

analyses, dry needling was not associated with clinically important reductions in shoulder or

neck pain when compared to other physical therapy modalities. The evidence is insufficient to

determine that the technology results in an improvement in the net health outcome.

For individuals who have myofascial trigger points associated with plantar heel pain who

receive dry needling of trigger points, the evidence includes a systematic review of randomized

trials. Relevant outcomes are symptoms, functional outcomes, quality of life, and treatment-

related morbidity. The systematic review included 6 randomized trials enrolling 395 patients

and found no overall difference in pain intensity in those treated with dry needling compared

with active control, placebo, or no intervention. However, pain intensity after at least 3

sessions, long-term pain intensity, and pain-related disability were improved. The systematic

review rated the evidence as low to moderate. The evidence for dry needling in patients with

plantar heel pain is limited by small patient populations and lack of blinding; therefore,

additional RCTs are needed to strengthen the evidence base. The evidence is insufficient to

determine that the technology results in the net health outcome.

For individuals who have myofascial trigger points associated with temporomandibular

myofascial pain who receive dry needling of trigger points, the evidence includes an RCT. The

relevant outcomes are symptoms, functional outcomes, QOL, and treatment-related morbidity.

One double-blind, sham-controlled randomized trial was identified; it found that one week after

completing the intervention, there were no statistically significant differences between groups

in pain scores or function (unassisted jaw opening without pain). There was a significantly

higher pain pressure threshold in the treatment group. Additional RCTs, especially those with a

8

sham-control group, are needed. The evidence is insufficient to determine that the technology

results in the net health outcome.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Practice Guidelines and Position Statements

Guidelines or position statements will be considered for inclusion in ‘Supplemental Information'

if they were issued by, or jointly by, a US professional society, an international society with US

representation, or National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Priority will be

given to guidelines that are informed by a systematic review, include strength of evidence

ratings, and include a description of management of conflict of interest.

American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapists (2009) issued a statement that dry

needling fell within the scope of physical therapist practice.

15

In support of this position, the

Academy stated that “dry needling is a neurophysiological evidence-based treatment

technique that requires effective manual assessment of the neuromuscular system….

Research supports that dry needling improves pain control, reduces muscle tension,

normalizes biochemical and electrical dysfunction of motor endplates, and facilitates an

accelerated return to active rehabilitation.”

Ongoing and Unpublished Clinical Trials

Some currently unpublished trials that might influence this review are listed in Table 4.

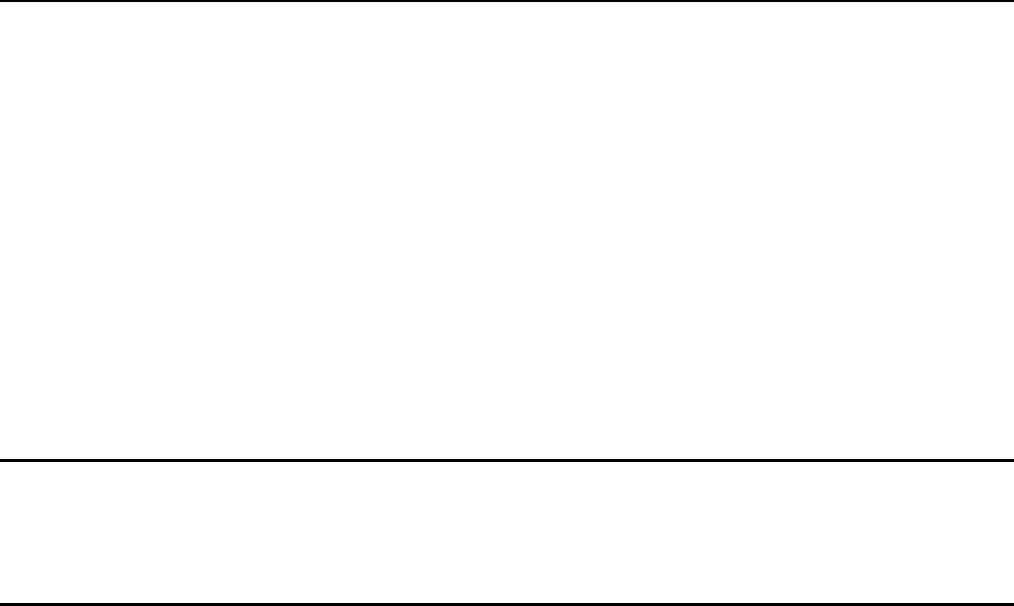

Table 4. Summary of Key Trials

NCT No.

Trial Name

Planned

Enrollment

Completion Date

NCT04851067

Dry Needling Versus Manual Therapy in Patients With Mechanical

Neck

Pain: A Randomized Control Trial

75

Mar 2022

NCT04726683

Trigger Point Dry Needling vs Injection in Patients With

Temporomandibular Disorders: A Randomized Placebo-controlled

Trial

80

Dec 2021

NCT03844802

Effectiveness of Real or Placebo Dry Needling Combined

With Therapeutic Exercise in Adults With Chronic Neck Pain

60

Mar 2022

NCT05624515

Efficacy of Dry Needling and Ischaemic Compression of the

Scapula Angularis Muscle in Patients With Cervicalgia.

Randomised Clinical Trial

80 Jan 2023

NCT05532098

Comparative Efficacy of Platelet Rich Plasma and Dry

Needling in Management of Anterior Disc Displacement of

Temporomandibular Joint

78 Mar 2023

NCT: national clinical trial.

9

Government Regulations

National:

There is no national coverage determination on dry needling of trigger points for myofascial

pain.

Local:

There is no local coverage determination on dry needling of trigger points for myofascial pain.

There is a LCD on Trigger Points, Local Injections (L34588, for services on or after

08/31/2023) which addresses only injections and not dry needling.

(The above Medicare information is current as of the review date for this policy. However, the coverage issues

and policies maintained by the Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services [CMS, formerly HCFA] are updated

and/or revised periodically. Therefore, the most current CMS information may not be contained in this

document. For the most current information, the reader should contact an official Medicare source.)

Related Policies

• Myofascial Trigger Point Injections-Dry Needling. Retired 07/01/15.

References

1. American Physical Therapy Association (APTA). Dry Needling. n.d.;

https://www.apta.org/patient-care/interventions/dry-needling. Accessed December 7, 2021.

2. Alvarez DJ, Rockwell PG. Trigger points: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician.

Feb 15 2002; 65(4):653-60. PMID 11871683

3. Charles D, Hudgins T, MacNaughton J, et al. A systematic review of manual therapy

techniques, dry cupping and dry needling in the reduction of myofascial pain and myofascial

trigger points. J Bodyw Mov Ther. Jul 2019; 23(3):539-546. PMID 31563367

4. Navarro-Santana MJ, Sanchez-Infante J, Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, et al. Effectiveness

of Dry Needling for Myofascial Trigger Points Associated with Neck Pain Symptoms: An

Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. Oct 14 2020; 9(10). PMID

33066556

5. Navarro-Santana MJ, Gomez-Chiguano GF, Cleland JA, et al. Effects of Trigger Point Dry

Needling for Nontraumatic Shoulder Pain of Musculoskeletal Origin: A Systematic Review

and Meta-Analysis. Phys Ther. Feb04 2021; 101(2). PMID 33340405

6. Llurda-Almuzara L, Labata-Lezaun N, Meca-Rivera T, et al. Is Dry Needling Effective for the

Management of Plantar Heel Pain or Plantar Fasciitis? An Updated Systematic Review and

Meta-Analysis. Pain Med. Jul 25 2021; 22(7): 1630-1641. PMID 33760098

7. Bagcier F, Yilmaz N. The Impact of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy and Dry Needling

Combination on Pain and Functionality in the Patients Diagnosed with Plantar Fasciitis. J

Foot Ankle Surg. Jul 2020; 59(4): 689-693. PMID 32340838

8. Cotchett MP, Munteanu SE, Landorf KB. Effectiveness of trigger point dry needling for

plantar heel pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. Aug 2014; 94(8): 1083-94. PMID

24700136

9. Eftekharsadat B, Babaei-Ghazani A, Zeinolabedinzadeh V. Dry needling in patients with

10

chronic heel pain due to plantar fasciitis: A single-blinded randomized clinical trial. Med J

Islam Repub Iran. 2016; 30: 401. PMID 27683642

10. Rahbar M, Kargar A, Eslamian F, Dolatkhah N. Comparing the efficacy of dry needling and

extracorporeal shock wave therapy in treatment of plantar fasciitis. J Mazandaran Univ

Med Sci. 2018;28(164):53-62.

11. Rastegar S, Baradaran Mahdavi S, Hoseinzadeh B, et al. Comparison of dry needling and

steroid injection in the treatment of plantar fasciitis: a single-blind randomized clinical trial.

Int Orthop. Jan 2018; 42(1): 109-116. PMID 29119296

12. Uygur E, Aktas B, Eceviz E, et al. Preliminary Report on the Role of Dry Needling Versus

Corticosteroid Injection, an Effective Treatment Method for Plantar Fasciitis: A Randomized

Controlled Trial. J Foot Ankle Surg. Mar 2019; 58(2): 301-305. PMID 30850099

13. Diracoglu D, Vural M, Karan A, et al. Effectiveness of dry needling for the treatment of

temporomandibular myofascial pain: a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled study.

J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2012; 25(4):285-90. PMID 23220812

14. Brady S, McEvoy J, Dommerholt J, et al. Adverse events following trigger point dry

needling: a prospective survey of chartered physiotherapists. J Man Manip Ther. Aug

2014; 22(3): 134-40. PMID 25125935

15. American Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapists. AAOMPT position statement on

dry needling. 2009;

http://aaompt.org/Main/About_Us/Position_Statements/Main/About_Us/Position_Statement

s.aspx?hkey=03f5a333-f28d-4715-b355-cb25fa9bac2c. Accessed January 6, 2023.

16. Para-García G, García-Muñoz AM, López-Gil JF, et al. Dry Needling Alone or in

Combination with Exercise Therapy versus Other Interventions for Reducing Pain and

Disability in Subacromial Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J

Environ Res Public Health. Sep 02 2022; 19(17). PMID 36078676

The articles reviewed in this research include those obtained in an Internet based literature search

for relevant medical references through December 6, 2023, the date the research was completed.

11

Joint BCBSM/BCN Medical Policy History

Policy

Effective Date

BCBSM

Signature Date

BCN

Signature Date

Comments

02/24/03 02/24/03 02/14/03 Joint policy established titled

Myofascial Trigger Points

03/21/05 03/21/05 02/28/05 Routine maintenance; policy retired.

07/01/15 04/21/15 05/08/15 Policy taken out of retirement, added

information on dry needling, also

added to title. Policy re-retired.

5/1/20 2/18/20 Unretired, completely rewritten with

focus on dry needling. Remains as

E/I service.

5/1/21 2/16/21 Routine maintenance. Reference 4

added. Policy statement unchanged.

Title changed from “Dry Needling of

Myofascial Trigger Points” to “Dry

Needling of Trigger Points for

Myofascial Pain”.

5/1/22 2/15/22 Routine maintenance. References

added; some references removed.

Policy statement unchanged.

5/1/23 2/21/23 Routine maintenance. Policy

statement unchanged. Vendor

Review: NA. (ky)

5/1/24 2/20/24 Routine maintenance. Policy

statement unchanged. Vendor

Review: NA. (ky)

Next Review Date: 1

st

Qtr. 2025

Pre-Consolidation Medical Policy History

Original Policy Date Comments

BCN: Revised:

BCBSM: Revised:

12

BLUE CARE NETWORK BENEFIT COVERAGE

P

OLICY: DRY NEEDLING OF TRIGGER POINTS FOR MYOFASCIAL PAIN

I. Coverage Determination:

Commercial HMO

(includes Self-Funded

groups unless otherwise

specified)

Not covered

BCNA (Medicare

Advantage)

See government section

BCN65 (Medicare

Complementary)

Coinsurance covered if primary Medicare covers the

service.

II. Administrative Guidelines:

• The member's contract must be active at the time the service is rendered.

• Coverage is based on each member’s certificate and is not guaranteed. Please

consult the individual member’s certificate for details. Additional information regarding

coverage or benefits may also be obtained through customer or provider inquiry

services at BCN.

• The service must be authorized by the member's PCP except for Self-Referral Option

(SRO) members seeking Tier 2 coverage.

• Services must be performed by a BCN-contracted provider, if available, except for

Self-Referral Option (SRO) members seeking Tier 2 coverage.

• Payment is based on BCN payment rules, individual certificate and certificate riders.

• Appropriate copayments will apply. Refer to certificate and applicable riders for

detailed information.

• CPT - HCPCS codes are used for descriptive purposes only and are not a guarantee

of coverage.

• Duplicate (back-up) equipment is not a covered benefit.