MICROSIMULATION TOOLS FOR THE

EVALUATION OF FISCAL POLICY

REFORMS AT THE BANCO DE ESPAÑA

Documentos Ocasionales

N.º 1707

Olympia Bover, José María Casado,

Esteban García-Miralles, José María Labeaga

and Roberto Ramos

2017

MICROSIMULATION TOOLS FOR THE EVALUATION OF FISCAL POLICY REFORMS

AT THE BANCO DE ESPAÑA

MICROSIMULATION TOOLS FOR THE EVALUATION OF FISCAL

POLICY REFORMS AT THE BANCO DE ESPAÑA

Olympia Bover, José María Casado, Esteban García-Miralles

and Roberto Ramos

BANCO DE ESPAÑA

José María Labeaga

UNED

Documento Ocasional. N.º 1707

2017

The Occasional Paper Series seeks to disseminate work conducted at the Banco de España, in the

performance of its functions, that may be of general interest.

The opinions and analyses in the Occasional Paper Series are the responsibility of the authors and,

therefore, do not necessarily coincide with those of the Banco de España or the Eurosystem.

The Banco de España disseminates its main reports and most of its publications via the Internet at the

following website: http://www.bde.es.

Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is

acknowledged.

© BANCO DE ESPAÑA, Madrid, 2017

ISSN: 1696-2230 (on line)

A

bstract

This paper presents the microsimulation models developed at the Banco de España for the

study of fiscal reforms, describing the tool used to evaluate changes in the Spanish personal

income tax and also the one for the value added tax and excise duties. In both cases

the structure, data and output of the model are detailed and its capabilities are illustrated

using simple examples of hypothetical tax reforms, presented only to illustrate the use of

these simulation tools.

Keywords: microsimulation, Spain, personal income tax, value added tax, excise duties.

JEL Classification: C81, D12, H20.

Resumen

Este documento presenta los modelos de microsimulación desarrollados por el Banco de

España para el estudio de reformas fiscales. Por un lado, describe la herramienta

de microsimulación que evalúa cambios en el impuesto sobre la renta de las personas físicas

(IRPF). Por otro lado, explica la herramienta del impuesto sobre el valor añadido (IVA) y los

impuestos especiales. Para cada una de estas dos herramientas, el documento detalla cómo se

estructura, los datos usados y los resultados que genera. También se muestran las capacidades

de estas herramientas mediante ejemplos sencillos de reformas fiscales hipotéticas, presentadas

exclusivamente para ilustrar el uso de estos simuladores.

Palabras clave: microsimulación, España, IRPF, IVA, impuestos especiales.

Códigos JEL: C81, D12, H20.

INDEX

Abstract 5

Resumen 6

1 Introduction 8

2 The Banco de España Personal Income Tax Microsimulation Model 10

2.1 The data 10

2.2 Framework of the Banco de España Personal Income Tax Microsimulation Model 11

2.2.1 The Spanish personal income tax 11

2.2.2 Parameters 14

2.2.3 Adjustment of the data in order to construct the 2015 baseline scenario 15

2.2.4 The output of the model 15

2.2.5 The accuracy of the model 15

2.2.6 Baseline results: personal income tax revenues and the distribution of tax

liabilities under the 2015 legislation 16

2.3 Simulation example 17

3 The Banco de España Indirect Tax Microsimulation Model 22

3.1 The data 22

3.2 Framework of the Banco de España Indirect Taxation Microsimulation Model 23

3.2.1 The value added tax and excise duties 23

3.2.2 Parameters 23

3.2.3 The demand system: behaviour in the Banco de España Indirect taxation

microsimulation model 28

3.2.4 The output of the model 32

3.2.5 The accuracy of the model 32

3.2.6 Baseline Results: indirect tax revenues and the distribution of tax liabilities

under the 2015 legislation 32

3.3 Simulation examples 35

3.3.1 A Change in VAT: a one point increase in the standard VAT rate 35

3.3.2 A Change in excise duties: an increase in the ad quantum tax on spirits 38

4 Conclusions 41

References 42

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 8 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

1 Introduction

This paper presents the microsimulation models developed at the Banco de España (BdE) for

the study of fiscal reforms involving changes in personal income taxation (PIT) and indirect

taxation (VAT and excise duties). The aim of the paper is to present the main features of the

tools and illustrate their capabilities using simple examples of tax reforms.

Microsimulation models are tools that simulate the effect of a reform on a representative

sample of individual agents (taxpayers, households, firms, etc.). They allow the aggregate and

the distributional effects of tax reforms to be studied, taking into account the heterogeneity

among individuals. As a consequence, they are a powerful tool for the development of decision-

support models in order to simulate and evaluate the impact of public policies.

Spurred by the availability of micro data and computer power, the use of

microsimulation methods to perform ex-ante and ex-post evaluation of fiscal reforms is

becoming more and more widespread. Currently, there is an extensive array of policy and

research institutions in Europe that have developed and maintain such models, such as the

Institute for Fiscal Studies in the UK (TAXBEN), the Institut des Politiques Publiques in France

(TAXIPP), the CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis (MIMOSI) and the Institute

for Social and Economic Research at the University of Essex, in collaboration with national

teams (EUROMOD, the European Commission sponsored tax-benefit microsimulation model),

to name a few. Microsimulation techniques can contribute to current fiscal policy debates and,

especially when it comes to modelling behavioural responses triggered by tax reforms, they

have attracted a lot of attention from the academic community.

The microsimulation model of direct taxation developed at the Banco de España

allows morning-after (first-round) aggregate and distributional effects of reforms in the Spanish

personal income tax (Impuesto sobre la Renta de las Personas Físicas or IRPF) to be

simulated. It allows a wide range of reforms stemming from changes in the parameters of the

tax code to be evaluated, in the absence of any behavioural reaction by agents.

In Spain, the first arithmetic microsimulation model of direct taxation was MOSIR

(Modelo de Simulación del Impuesto sobre la Renta) developed by Castañer and Santos (1992)

at the Instituto de Estudios Fiscales (IEF) using administrative records. Levy et al. (2001)

presented ESPASIM, a microsimulation model of direct taxation, as well as of social

contributions, indirect taxation and excise duties. The database for the microsimulator of direct

taxation was the ECHP. In the early 2000s the IEF created a microsimulation unit that built

SIRPIEF, which performed both arithmetic and behavioural simulations based on survey data

from the ECHP. A summary of this tool is contained in Sanz et al. (2004) and their labour

supply model borrows from Labeaga and Sanz (2001). Oliver and Spadaro (2004) developed

GLADHISPANIA, a combined arithmetic-behavioural tool based on data from the ECHP. Also

at the IEF, Moreno et al. (2010) developed Microsim-IEF, and Onrubia et al. (2013) developed

MODELAIR, both arithmetic models using administrative records. There are many other

applications of microsimulation that use Spanish direct-taxation data as well as tax-benefit

models. Some examples are presented by García et al. (1997), Badenes et al. (1998) and

García and Suárez (2002, 2003).

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 9 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

The Banco de España microsimulation model for indirect taxation allows changes in

the value added tax (Impuesto sobre el Valor Añadido or IVA) and excise duties (impuestos

especiales) to be simulated. In addition to morning-after effects, it captures the behavioural

response of households through the estimation of a demand system. Therefore, in addition to

first-round effects, the tool allows households’ behavioural reaction to price changes stemming

from a tax reform (second-round effects) to be predicted.

In Spain, the first tool for indirect taxation was developed by Labeaga and López

(1995), whose complete demand model was presented in Labeaga and López (1994). The

microsimulation unit at the IEF also developed a tool for indirect taxation, SINDIEF (Simulador

de Impuestos Indirectos del Instituto de Estudios Fiscales). Sanz et al. (2003) provide a

summary of its functioning. Examples of microsimulation papers dealing with indirect taxes and

excise duties are Labeaga and López (1997) and Labandeira and Labeaga (1999). An overall

discussion of microsimulation can be found in Bourguignon and Spadaro (2006), while a

summary for Spain is contained in Ayala et al. (2004).

The models for PIT and for VAT and excise duties both provide a comprehensive

evaluation of tax reforms, by accounting for the effects relating to tax collection, effective

tax rates, winners and losers and inequality indices. These effects are disaggregated by

income decile and age group. Moreover, the model for indirect taxation provides results

for welfare changes.

The rest of this paper presents the two microsimulation models, starting with the

personal income tax model and afterwards the VAT and excise duties model.

1

1 Both tools are accompanied by a User Guide that explains how to execute them in order to simulate different policies.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 10 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

2 The Banco de España Personal Income Tax Microsimulation Model

This model simulates the tax liabilities stemming from the Spanish personal income tax

(Impuesto sobre la Renta de las Personas Físicas or IRPF) for a large representative sample of

taxpayers. The model incorporates most of the tax code specificities that determine the

calculation of tax liabilities. Therefore, it allows a wide range of reforms, such as those involving

marginal tax rates, tax deductions, tax credits, and exemptions, to be simulated.

The model is an arithmetic tool that provides morning-after effects of the reform being

simulated insofar as behavioural effects, such as the variation in employment status or hours

worked, are not taken into account. The outcome of the model includes an estimation of total

tax revenues, winners and losers, and changes in average tax rates by income decile and age

group. Furthermore, it provides measures of inequality and redistribution. It also allows the

simulated micro data to be saved for the performance of further analysis.

2.1 The data

The data used by the model is a (stratified) random sample of 2013 tax returns namely, the

MUESTRA IRPF 2013 IEF-AEAT (Declarantes). As more recent data become available they will

be incorporated into the model updates. The sample size (in 2013) is about 2.2 million tax

returns, which corresponds roughly to 11% of the population. They pertain to the 15 regions

with a common tax regime and the two autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla. Therefore, they

exclude the two regions with special tax regimes (the Basque Country and Navarre). For a

detailed description of this dataset see López et al. (2016).

The dataset contains most of the fiscal variables and socio-demographic characteristics

included in the tax return (modelo 100). Therefore, it contains very precise information on income

sources and tax benefits, as well as some family characteristics, such as the number of

dependent children, other dependent relatives, disability and location. The detailed information in

the dataset allows individual tax liabilities to be accurately simulated and a wide range of reforms

to be modelled. Yet the fact that no information on the employment status of the taxpayer is

provided prevents the modelling of behavioural responses following tax reforms.

Tax returns are of two types: single tax returns, filed at the individual level, and joint tax

returns, filed by (mainly) married couples. In joint tax returns, incomes are pooled together and

are eligible for an additional deduction on top of those available for single tax returns. Apart

from these and other small differences, the computation of tax liabilities is similar. The decision

on which type to choose is taken by the taxpayer. In general, joint tax returns benefit couples

when one spouse earns little or no income, as well as single-parent families when the children

do not have any income.

2

The model abstracts from the choice between single or joint tax

returns, taking it as given. In 2013, around 79% of tax returns were single tax returns, the rest

being joint ones.

Table 1 reproduces some of the items included in Table 2 of López et al. (2016). It

shows that the sample aggregates constructed from the micro data provide an accurate

representation of the population aggregates, the differences being smaller than 1.5% in all

cases, except that of save income stemming from gains and losses.

2 Single parents can file a joint tax return despite being only one individual, benefiting from the corresponding deduction.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 11 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

The sample of tax returns is complemented by an additional dataset containing

information on taxes withheld at source corresponding to people with no obligation to file a tax

return and who do not do so, even though they would very likely obtain a refund. This dataset,

known as “no obligados, no declarantes”, is not included in the microsimulation model and

therefore this population is excluded from the simulations. In 2013 it amounted to 2.3 million

persons and €2.1 billion of withholdings.

2.2 Framework of the Banco de España Personal Income Tax Microsimulation Model

2.2.1 THE SPANISH PERSONAL INCOME TAX

The model follows the personal income tax code in order to simulate the tax liabilities of each

taxpayer. Many specific parameters of the tax code are left free in order to allow reforms to be

simulated. When these parameters take the actual value of the tax code, the model replicates

(approximately)

3

the actual tax liability data.

Figure 1 provides a simplified diagram of the tax code in 2013. Gross income subject to

the tax can be of several types: labour income, capital income (both financial and real-estate) and

self-employment income. Certain deductible expenses can be subtracted from gross income,

including, for example, the social security contributions paid by the employee, a given amount for

labour income earners, and economic expenses associated with the business activity.

Gross income net of deductible expenses is classified into two groups, which are

subsequently taxed at different rates. On the one hand, “general income” comprises mainly

labour income, self-employment income and some capital income. On the other hand, “savings

income” includes the largest portion of capital income. To each type of income a set of

deductions is applied. For example, to general income a deduction for joint filing as well as one

for contributions to private pension plans, among others, can be applied. If the taxpayer is

entitled to deduct an amount exceeding her general income, she can apply the remainder

3 Some small deviations between the actual data and the simulation may occur due to rare instances in which

deductions exceed the maximum amount entitled by law or there exist slight discrepancies between the reported data

and the result of the application of the tax code. Also, some tax benefits depend on variables that are either not

observed or are only partially observed, hence some assumptions were made in order to ease the simulation. For

example, siblings filing individual tax returns may be entitled to share the family allowance for parents living with the

taxpayer, depending on the number of months of cohabitation, a variable that is not observed. Hence, a value of

12 months of cohabitation was assumed. Moreover, since some tax benefits depend also on previous variables of the

tax code, errors may accumulate or cancel each other.

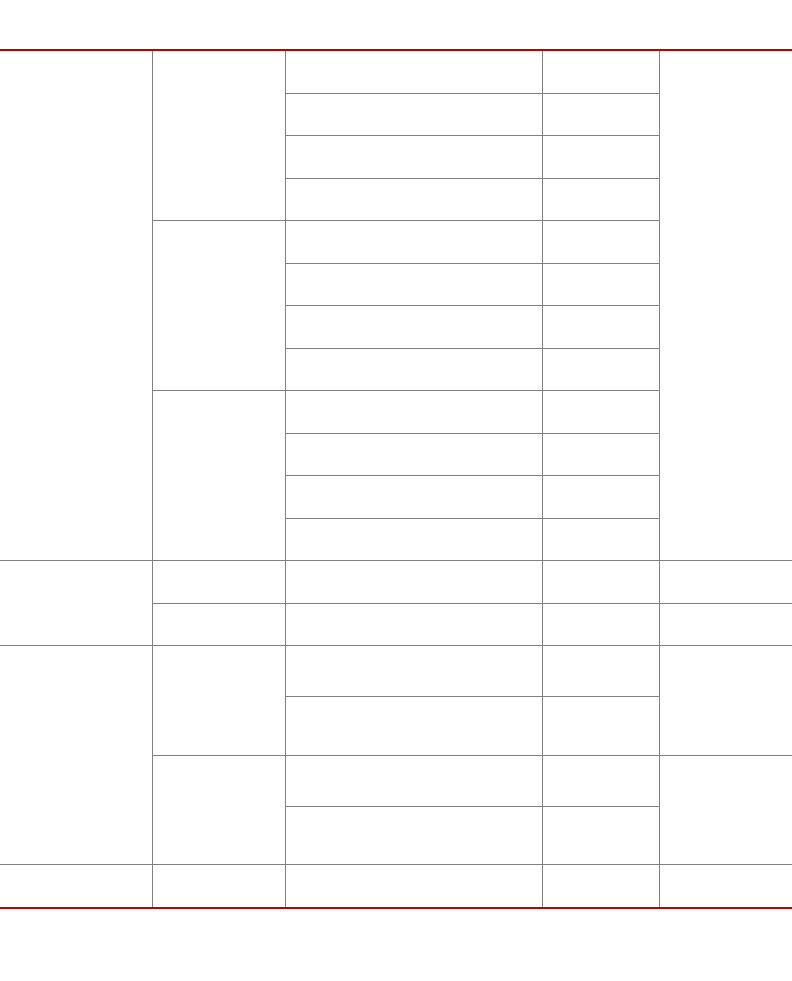

ACCURACY OF THE PERSONAL INCOME TAX MICRO DATA TABLE 1

€bn Tax form box

Sample

aggregate

Population

aggregate Difference

Gross monetary labour income 1 375.7 375.5 0.0%

Gross capital income 28+38 18.4 18.4 0.0%

Self-employment income 125+150+180 22.5 22.4 0.4%

Income from gains and losses 361+368 8.0 8.4 -4.8%

General taxable income 415 327.1 327.0 0.0%

Savings taxable income 419 24.7 25.0 -1.4%

Family allowance

(general and savings income) 439+440 109.7 109.8 -0.2%

Tax liabilities

(gross of working mother tax credit) 511 67.0 67.1 -0.2%

SOURCE: López et al. (2016).

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 12 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

of some deductions to her savings income. Income minus deductions is the general taxable

income and the savings taxable income.

Two different tax schedules are applied to each type of income, a state schedule and

a regional schedule. This stems from the fact that around 50% of the personal income tax

revenue is transferred to the regions, which are entitled to modify their own tax schedule and to

introduce their own tax credits. In 2013, the general state schedule consisted of 7 tax bands

and a top marginal rate of 30.5%. On top of this, as mentioned, the regional general tax

schedule is applied. For example, that of the Madrid region comprised four tax bands and a

top marginal rate of 21.4%; that of Catalonia had 6 tax bands and a top marginal tax rate of

25.5%. Madrid taxpayers therefore faced a top marginal rate of 51.9%, while taxpayers in

Catalonia were subject to a top marginal tax rate of 56%.

The savings tax schedule is much less progressive. In 2013 the state part consisted of

3 bands and a top marginal rate of 16.5%, whereas the regional part consisted of 2 bands and

a top rate of 10.5%. In this case, the savings regional tax schedule did not vary across regions.

Once the general income tax liabilities are computed (state and regional components),

they are reduced by the family allowance (again, with state and regional variability, although in

this case they are all similar). The family allowance is computed by applying the general tax

schedule to an amount that depends on the characteristics of the taxpayer and her family,

such as her age, number of dependent children, number of dependent parents, and disability

of the taxpayer and of the dependent members of her family.

After subtracting the family allowance, the state general income and state savings

income tax liabilities are pooled together. Similarly, the regional general income and regional

savings income tax liabilities are added together.

To these two types of tax liabilities a set of tax credits is applied, some of which are

state or region specific and some of which pertain to both. Among them are the tax credit on

house purchases (if they were made before 2013), the large set of regional tax credits and a tax

credit for low labour income earners. The state and regional tax liabilities net of these and the

other tax credits are then pooled together.

Finally, to these pooled tax liabilities, which cannot be below zero, a refundable tax

credit is applied in the case of employed mothers with children below the age of three. The final

tax liabilities are obtained after the subtraction of this tax credit.

It must be noted that when running the microsimulation model, the baseline scenario

(against which the reform scenario is compared) is in general the 2015 tax code. As we explain

later, this forces some adjustments to be made to the data. Specifically, we update the sample

weights and the income data by using information on the number of taxpayers by region and

on aggregate income growth by income source, respectively. Moreover, we apply the 2015 tax

code to the adjusted data. This is very relevant, because in 2015 a tax reform was

implemented, involving important changes in the tax code. For example, the number of state

tax bands was reduced from 7 to 5, and the state tax rates were significantly reduced. For

instance, the top state marginal tax rate was reduced from 30.5% to 22.5%. Moreover, some

regions changed their tax schedules. Also, the family allowance was increased and new

refundable tax credits associated with family characteristics were granted. Regarding

deductions, some of them were reduced, for example, the one for labour income earners

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 13 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

and that for contributions to private pension plans. All these changes are modelled, whenever

possible, in the microsimulation tool.

SIMPLIFIED DIAGRAM OF THE PERSONAL INCOME TAX CODE (2013) FIGURE 1

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 14 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

2.2.2 PARAMETERS

The microsimulation model considers a large set of parameters that characterise the tax code

and therefore determine the computation of tax liabilities. The number of parameters

incorporated in the microsimulation tool is around 1,500, including many specific to each

region. Currently, the personal income tax codes of 2013, 2014 and 2015 are modelled. The

simulation exercise consists in modifying this set of parameters in order to obtain the resulting

tax liabilities under alternative tax codes. Some examples of possible reforms that the model

can simulate are the following.

a) Switching tax benefits off and on

Almost every tax deduction and tax credit is associated with a binary parameter that

determines whether it is applied or not. Therefore, the model can simulate, for

example, a restriction on certain tax benefits. Furthermore, the model can simulate

the conversion of some tax deductions (subtracted from the tax base) to tax credits

(subtracted from the tax liabilities). Also, it allows the form of application of some tax

benefits to be changed, for instance from being a fraction of a particular variable

to being a fixed amount.

b) Changing the upper and lower bounds of tax benefits

The amounts of many tax benefits are restricted by fixed quantities or by a fraction of

other variable(s). As long as the microsimulation includes these restrictions, it allows

them to be modified. It must be stressed that the micro data already incorporate the

actual restrictions, so that the model cannot simulate increases in many tax benefits.

This is the case when the underlying variable giving rise to the benefit is unobserved.

For example, the deduction on the amount of charity donations is capped at €500.

Insofar as the total amount donated is unobserved, an increase in this tax benefit to,

say, €600 cannot be simulated, since it is not possible to know for which taxpayers

the actual restriction is relevant. In these cases, only a reduction (or complete

elimination) of the tax benefit can be simulated.

c) Adjusting the monetary values of tax benefits

For those tax benefits that consist of a fixed monetary value or that depend on

observable characteristics of the taxpayer, the model allows the value of the tax

benefit to be freely adjusted. This is the case, for example, of the large set of family

allowances.

d) Changing the classification of income sources

The model allows changes in the classification of some income sources between

general income and savings income, or their exclusion from taxable income. This is

useful in order to simulate reforms to the manner in which each type of income

is taxed. For example, a change in the way in which capital (savings) income is taxed

to make it the same as for labour income could be simulated.

e) Modifying the tax schedules

The model readily permits modification of the state and regional tax schedules, both

for general income and savings income.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 15 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

2.2.3 ADJUSTMENT OF THE DATA IN ORDER TO CONSTRUCT THE 2015 BASELINE SCENARIO

In the current version of the microsimulation model, the baseline scenario, against which the

reform scenario is compared, usually corresponds to 2015. Given that the data pertain to

the year 2013, this requires an update of the data. In this regard, two adjustments are carried

out. First, the sample weights are adjusted by considering the changes in the number of

taxpayers by region. Second, the income data are adjusted using aggregate income changes

by income source. The source of these aggregate changes is the AEAT.

4

Then, in order to

construct the 2015 baseline scenario, the microsimulation model with the parameters

characterising the 2015 tax code is run on the adjusted micro data. Note also that a similar

procedure is carried out if the baseline scenario chosen is the 2014 tax code. If the baseline is

2013, no adjustment to the data is performed.

2.2.4 THE OUTPUT OF THE MODEL

The model simulates the set of variables comprising the tax return of each sampled taxpayer in

both the baseline and the reform scenarios. It then aggregates certain variables either

by income decile or age group in order to perform some comparisons. Specifically, it provides

information on total revenue, average tax rates, winners and losers, and several inequality

measures, such as the distribution of after-tax income, Lorenz curve, Gini coefficient and some

percentile ratios. A standard output from the model can be observed in the example presented

in Section 2.3. The program also allows the simulated micro dataset to be saved, so that

further analysis can be performed.

2.2.5 THE ACCURACY OF THE MODEL

In this section we compare some aggregates produced by the microsimulation model for

the tax legislation of 2013, 2014 and 2015 with the corresponding aggregates reported by the

Spanish Tax Agency (AEAT). Note that for 2014 and 2015 the data have been updated as

described above. The results are reported in Table 2.

5

As can be seen, for each single item the sample aggregate is very close to the

population aggregate, the largest deviation being only 0.8%. This suggests that the model

yields an accurate description of overall income and tax liabilities.

4 Estadísticas de los declarantes del Impuesto sobre la Renta de las Personas Físicas (IRPF).

5 Table 2 does not include the withholdings from persons under no obligation to file a tax return and who decide not to

do so.

SAMPLE AGGREGATES FROM THE MICROSIMULATION MODEL COMPARED WITH

POPULATION AGGREGATES

TABLE 2

€bn

Model AEAT Difference (%)

2013 2014 2015 2013 2014 2015 2013 2014 2015

Number of tax-payers (million)

19.2 19.3 19.5 19.2 19.4 19.5 -0.1 -0.1 -0.1

Income ("Rendimientos")

421.4 428.2 447.0 421.8 428.6 447.0 -0.1 -0.1 0.0

Tax Base ("Base Liquidable")

351.8 358.0 375.7 352.2 357.2 375.3 -0.1 0.2 0.1

Tax Liabilities before Tax Credits ("Cuota Íntegra")

72.0 73.5 71.0 72.1 73.2 71.0 -0.1 0.4 0.0

Tax Liabilities before Refundable Tax Credits

("Cuota Resultante de la Autoliquidación")

67.0 68.5 66.9 67.1 68.4 67.0 -0.2 0.0 -0.2

Tax Liabilities after Refundable Tax Credits

66.2 67.7 65.1 66.4 67.7 65.6 -0.2 0.0 -0.8

SOURCE: BdE PIT Microsimulation Model.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 16 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

2.2.6 BASELINE RESULTS: PERSONAL INCOME TAX REVENUES AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF TAX

LIABILITIES UNDER THE 2015 LEGISLATION

This section presents an overview of the distribution of revenue and average effective tax rates

across income deciles, as simulated by the model under the 2015 legislation.

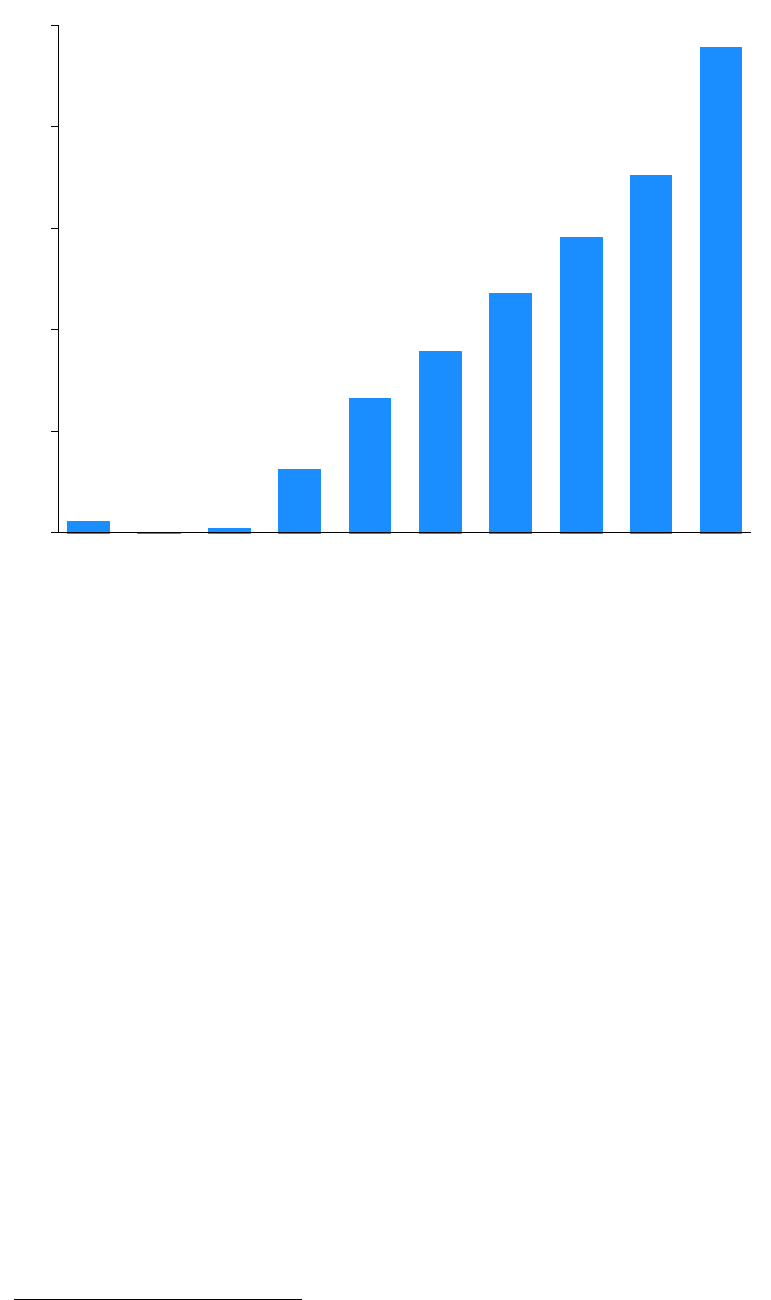

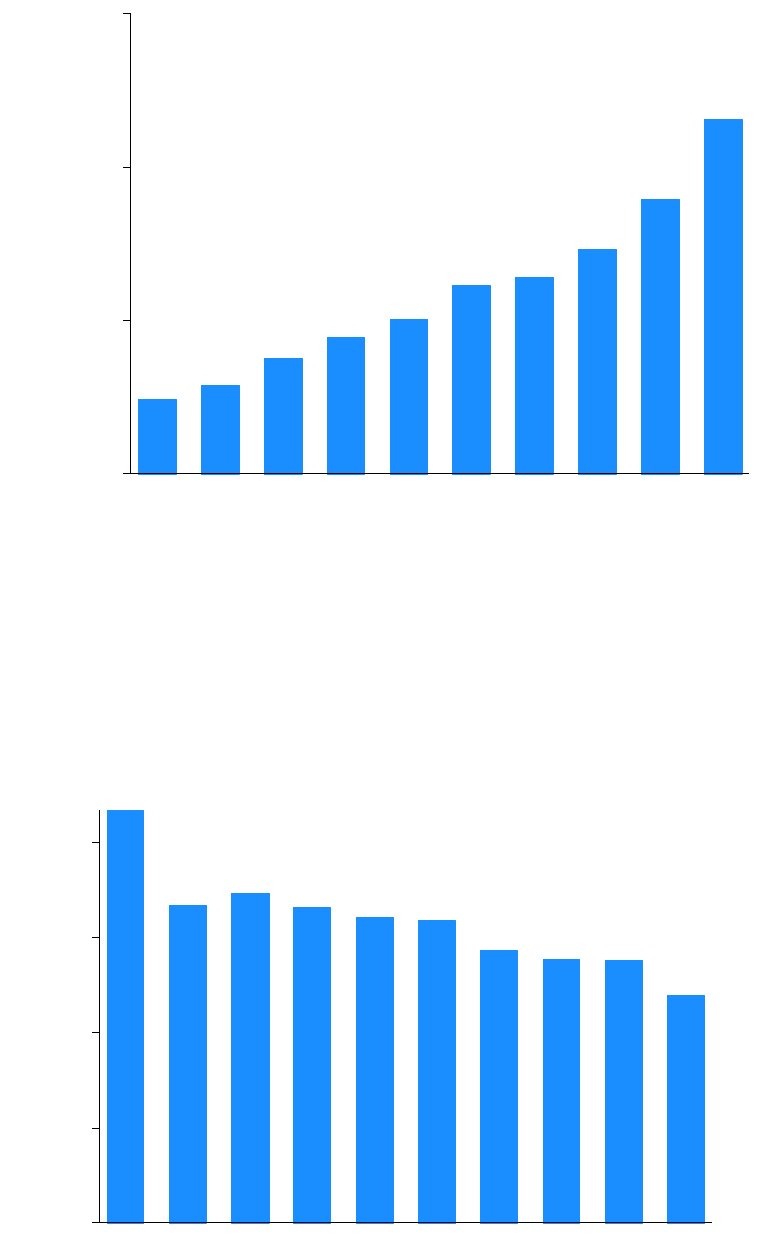

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the PIT revenue by income decile. Total revenue,

amounting to €65.1 billion, is very unevenly distributed, as expected from a progressive tax.

The first three deciles barely contribute to tax revenue, while the top 10% accounts for more

than half of it.

Figure 3 displays the average effective tax rates by income decile, that is, the ratio of

tax liabilities minus tax credits to gross income net of some deductions (base imponible). We

use this variable in the denominator because we do not observe gross income from some

income sources, such as self-employment income. Also, note that taxpayers whose tax

liabilities are negative are assigned a zero tax rate. As can be observed, the mean average

effective tax rates increase with income.

6

The bottom 30% of taxpayers face rates of virtually

0%, while tax rates for the well-off are around 24%, on average.

6 Average tax rates in respect of (observed) gross income are, on average, around two percentage points higher for

deciles 4 to 10 and 0.1 percentage points higher for deciles 1 to 3.

PIT REVENUE BY INCOME DECILE (2015) FIGURE 2

SOURCE: BdE PIT Microsimulation Model.

-118

-127

-115

447

1,677

2,958

4,905

7,587

11,779

36,066

0 10,000 20,000 30,000 40,000

Million euros

12345678910

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 17 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

2.3 Simulation example

In this section, we illustrate the outcome produced by the BdE PIT Microsimulation Tool by

simulating a hypothetical reform that should not be considered to be proposed by the

Banco de España. This consists of converting the tax benefit stemming from contributions

to private pension plans from a tax deduction (subtracted from the tax base, the current

situation or baseline scenario) to a (non-refundable) tax credit (subtracted from tax liabilities,

the reform scenario).

Under the 2015 legislation, the contributions made by taxpayers to private pension

plans could be deducted from the tax base, with limits set at €8,000 or €2,500 when the plan’s

beneficiary is herself or her spouse, respectively. The reform we simulate, instead applies this

tax benefit directly to tax liabilities, which cannot turn negative as a result (non-refundable tax

credit). We set the amount of the tax credit in order to roughly generate a revenue-neutral

reform. Specifically, the maximum amounts are set at €600 for contributions to own pension

plans and €300 for contributions to a spouse’s pension plan.

As a result of this hypothetical reform, set out for the purposes of illustration, we

estimate that total revenue would decrease by €68 million, the well-off being the hardest-hit on

aggregate (see Figure 4).

7

The aggregate tax liabilities of the bottom 30% would hardly change,

since the incidence of this tax benefit on this part of the income distribution is very low. The tax

revenue raised from deciles 4 to 9 would decrease by around €480 million, which would be

partially offset by an increase in the tax raised from the top decile.

7 Note that this reform does not affect withholdings. Policy actions that do change them would entail an additional

change in revenue from individuals whose income is withheld at source but who do not file a tax return.

MEAN AVERAGE EFFECTIVE TAX RATE BY INCOME DECILE (2015) FIGURE 3

SOURCE: BdE PIT Microsimulation Model.

0.55

0.02

0.23

3.15

6.67

8.94

11.83

14.56

17.62

23.93

0 5 10 15 20 25

%

12345678910

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 18 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

Figure 5 shows the percentage of winners and losers by income decile, while Table 3

summarises the quantitative effects of the reform. From deciles 4 to 9 almost all taxpayers are

better off, while in the top decile those affected by the reform are roughly evenly split between

winners and losers. Note that winners are those whose tax liabilities decrease as a result of the

tax change, while losers are those whose tax liabilities increase.

8

On average, winners in deciles

5 to 10 pay around €300 less in taxes while losers in the top decile face an increase of around

€1,500 in tax liabilities.

8 Tax increases and decreases are defined to occur when tax liabilities change by more than €1 or 0.001%.

REVENUE CHANGE BY INCOME DECILE FIGURE 4

SOURCE: BdE PIT Microsimulation Model

413

-115

-105

-90

-82

-59

-28

-1

-0

-0

-100 0 100 200 300 400

Million euros

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 19 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

Table 3 presents the numbers behind Figure 5, including the number of individuals

in each category for each income decile, as well as the total and average revenue change

within each category and decile.

PERCENTAGE OF WINNERS AND LOSERS BY INCOME DECILE FIGURE 5

SOURCE: BdE PIT Microsimulation Model.

WINNERS AND LOSERS TABLE 3

Total Winners Losers Neutral

Deciles Population

Gain (+) or

loss (-)

Avg. gain or

loss

Number % Avg. gain Number % Avg loss Number %

millions million € € millions € millions € millions

1 1.9 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 546.9 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.9 100.0

2 1.9 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 463.9 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.9 100.0

3 1.9 1 0.5 0.0 0.5 89.8 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.9 99.5

4 1.9 28 14.5 0.1 5.3 275.1 0.0 0.0 119.6 1.8 94.6

5 1.9 59 30.1 0.2 8.9 338.7 0.0 0.1 148.5 1.8 91.0

6 1.9 82 42.3 0.2 12.3 346.9 0.0 0.3 160.0 1.7 87.4

7 1.9 90 46.2 0.3 14.1 343.7 0.0 0.7 357.8 1.7 85.2

8 1.9 105 54.0 0.3 17.6 339.9 0.0 1.3 473.3 1.6 81.1

9 1.9 115 59.3 0.4 22.1 339.8 0.1 3.3 483.7 1.5 74.6

10 1.9 -413 -212.2 0.5 25.3 320.0 0.4 19.5 1,506.7 1.1 55.3

Total 19.5 68 3.5 2.1 10.6 333.8 0.5 2.5 1,266.9 16.9 86.9

SOURCE: BdE PIT Microsimulation Model.

0 20 40 60 80 100

%

12345678910

Winners Losers Neutral

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 20 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

Figure 6 shows the change in the (mean) average tax rate by income decile. The top

decile experiences a 0.2 percentage point increase in average tax rates, while the 8th decile

undergoes a similar effect of the opposite sign. The average tax rates of deciles 5 to 7 diminish

by slightly more than 0.2 percentage points.

Table 4 shows different measures of inequality of after-tax income before and after the

reform. Since the worse-off are concentrated in the well-off group, the Gini coefficient slightly

decreases. However, most of the other inequality indices increase, especially the 50/10 and the

75/25 ratios, since there is a non-negligible amount of winners concentrated in the middle of

the income distribution. It is worth noting nevertheless that the changes in the inequality indices

are rather small.

9

9 The model produces additional outputs, such as histograms of after-tax income and Lorenz curves. Moreover, it

allows the effects of the reform to be simulated by age group, rather than by income decile. These outputs are not

presented for space considerations.

CHANGE IN THE EFFECTIVE AVERAGE TAX RATE BY INCOME DECILE FIGURE 6

SOURCE: BdE PIT Microsimulation Model.

0.20

-0.17

-0.20

-0.21

-0.23

-0.21

-0.14

-0.01

-0.00

-0.00

-0.2 -0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2

Percentage Points

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 21 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

MEASURES OF INEQUALITY OF AFTER-TAX INCOME TABLE 4

Indices Pre-Reform Post-Reform Change (pp)

90/10 6.3 6.3 0.0014

90/50 2.1 2.1 -0.0034

50/10 3.1 3.1 0.0057

75/25 2.4 2.5 0.0039

75/50 1.5 1.5 0.0001

50/25 1.6 1.6 0.0025

Gini 0.38 0.38 -0.0007

SOURCE: BdE PIT Microsimulation Model.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 22 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

3 The Banco de España Indirect Tax Microsimulation Model

This section introduces the microsimulation tool that calculates the Spanish VAT and excise

duties (IVA and impuestos especiales). The tool allows for changes in VAT on up to

119 different non-durable goods and for changes in the excise duties levied on four goods.

These reforms can be implemented jointly, which is especially useful, since, in the case of

goods subject to both VAT and excise duties, these taxes interact with each other. The tool

allows for morning-after effects of reforms, but it can also simulate hypothetical reforms taking

into account households’ behavioural reaction to price changes, given a level of expenditure on

non-durable goods, through the parameters estimated for a complete demand system.

3.1 The data

The main data used for this microsimulation tool are obtained from the Spanish Household

Expenditure Survey (Encuesta de Presupuestos Familiares, EPF). The sample contains 22,000

households per year with information on household expenditure for 255 commodities,

accounting for 78% of the expenditure according to the National Accounts in 2015. The

dataset also includes a large set of socio-demographic variables. The month in which

the survey was answered can be observed,

10

which allows the expenditure of each household

to be linked to the monthly prices for a particular commodity. The interviews of households are

uniformly distributed across each year.

In particular, the most recent wave of the survey is used for simulation purposes

(2015), and the pooled cross-sectional sample of the years 2006-2015 is used to estimate the

coefficients of the demand system. The sample contains a total of 217,000 observations.

The aggregation of goods into expenditure groups for the demand system is mainly driven by

heterogeneity among goods but also by the structure of Spanish indirect taxation. Each good

subject to excise duties is maintained as a separate group in the system (with the exception of

electricity) but is estimated jointly with the other groups of goods.

The second dataset used is the Spanish Consumer Price Index (Índice de Precios del

Consumo, IPC) containing monthly time series of price indices at national and regional level.

For the estimation of the demand system, monthly price indices by region (comunidad

autónoma) are used to obtain as much variation in prices as possible. In this case, the prices

are disaggregated into 37 goods, which are then aggregated into the 13 expenditure groups of

the demand system (described below). Official price indices assume a common consumption

basket across regions and therefore take the same value in the base year (2005). To correct for

this, a factor is applied to account for differences in price levels across regions, using the

estimations of Costa et al. (2015) for 2012. Hence, there are 17 x 10 x 12 (regions x years

x months) different prices for each commodity (i.e. 2,040).

For the simulation, the 2015 price index at national level is used, which offers a greater

disaggregation, into 119 prices.

11

These are the goods for which the microsimulator can

simulate changes in tax rates (VAT and excise duties if applicable).

10 This information was obtained under a special request to the Spanish Statistical Office (www.ine.es).

11 The initial disaggregation has 126 goods but some of them are combined due to interruptions and changes in the

series.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 23 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

3.2 Framework of the Banco de España Indirect Taxation Microsimulation Model

The indirect taxation microsimulation model calculates the VAT and excise duties paid by each

household. It allows for the behavioural reactions of households to changes in prices arising

from taxation. Therefore, in addition to first-round or morning-after effects (changes in prices

and tax revenue resulting from changes in taxes keeping each household’s expenditure

constant for each commodity) we can estimate second-round effects arising from demand

adjustments. This adjustment is allowed in the form of substitution between commodities,

subject to a constant total level of consumption of non-durable goods. The model can

therefore be used for analyses such as running a simulation using the current VAT and excise

duty legislation to predict tax liabilities and revenues, making comparisons with hypothetical

reforms of the tax legislation (VAT or excise duty rates), and calculating welfare changes.

3.2.1 THE VALUE ADDED TAX AND EXCISE DUTIES

VAT is basically a tax on consumption expenditure. All sales are taxed, but registered traders

are allowed to deduct the tax charged on their inputs, so that the tax is effectively levied on the

value added at each stage of the production process. The only VAT that cannot be reclaimed is

that charged to the final purchaser and, therefore, only final consumption is taxed. Producers

can assume part of the increase in prices arising from a tax reform and this can be accounted

for in the simulations. A complete pass-through is usually assumed, except when the aim is to

obtain the short-run effects of reforms. In any case, the sensitivity of simulations to different

rates of pass-through can also be analysed.

Given the way in which VAT functions, the microsimulation model calculates

households’ tax liabilities for each good consumed before and after a reform. To simulate tax

reforms, the tax rates under the current legislation are deducted from the prices, and then the

new tax rates are added to obtain new prices. The demand system uses these new prices to

predict new shares of consumption of the different goods, allowing for substitution between

non-durable goods subject to a given total level of expenditure. As a result, the tax liabilities

paid by each household after the reform are obtained, having accounted for behavioural

responses to price changes.

3.2.2 PARAMETERS

Three types of parameters are used. First, the VAT tax rates that apply to each of the

119 goods of the national price index disaggregation. Second, 19 parameters that define the

different excise duties applied to the four goods subject to excise duties. Finally, the model

uses the behavioural parameters estimated by the demand system, explained in Section 3.2.3.

VAT Parameters

The VAT parameters for the 2015 legislation can take four different values, corresponding to

the four different tax rates existing: exempt (0%), super-reduced (4%), reduced (10%), and

standard (21%). A list of the 119 goods considered in the microsimulator and their

corresponding VAT tax rate in 2015 is shown in Table 5.

12

These are the goods for which we

can simulate a reform of the VAT rate.

12 For groups of goods taxed at different tax rates, a weighted average has been calculated using the price weights from

the IPC.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 24 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

Good VAT Good VAT Good VAT Good VAT

Arroz 10 Alimentos para bebé 10 Aparatos de calefacción y de aire

acondicionado

21 Soporte para el registro de imagen y

sonido

21

Pan 4 Café, cacao e infusiones 10 Otros electrodomésticos 21 Juegos y juguetes 21

Pasta alimenticia 10 Agua mineral, refrescos y zumos 10 Reparación de electrodomésticos 21 Grandes equipos deportivos 21

Pastelería, bollería y masas cocinadas 10 Espirituosos y licores 21 Cristalería, vajilla y cubertería 21 Otros artículos recreativos y deportivos 21

Harinas y cereales 4 Vinos 21 Otros utensilios de cocina y menaje 21 Floristería y mascotas 15.5

Carne de vacuno 10 Cerveza 21 Herramientas y accesorios para casa y

jardín

21 Servicios recreativos y deportivos 21

Carne de porcino 10 Tabaco 21 Artículos de limpieza para el hogar 21 Servicios culturales 21

Carne de ovino 10 Prendas exteriores de hombre 21 Otros artículos no duraderos para el

hogar

21 Libros de entretenimiento y de texto 4

Carne de ave 10 Prendas interiores de hombre 21 Servicio doméstico y otros servicios

para el hogar

21 Prensa y revistas 4

Charcutería 10 Prendas exteriores de mujer 21 Medicamentos y otros productos

farmacéuticos

4 Material de papelería 21

Preparados de carne 10 Prendas interiores de mujer 21 Material terapéutico 21 Viaje organizado 10

Otras carnes y casquería 10 Prendas de vestir de niño y bebé 21 Servicios médicos y paramédicos no

hospitalarios

21 Educación Infantil 0

Pescado 10 Complementos y reparación y limpieza

de prendas de vestir

21 Servicios dentales 0 Enseñanza obligatoria 0

Crustáceos y moluscos 10 Calzado de hombre 21 Servicios hospitalarios 0 Bachillerato 0

Pescado en conserva y preparados 10 Calzado de mujer 21 Automóviles 21 Enseñanza superior 0

Leche 4 Calzado de niño y bebé 21 Otros vehículos 21 Otras enseñanzas 0

Otros productos lácteos 10 Reparación de calzado 21 Repuestos y accesorios de

mantenimiento

21 Restaurantes, bares y cafeterías y

Cantinas

10

Quesos 4 Alquiler de vivienda 0 Carburantes y lubricantes 21 Hoteles y otros alojamientos 10

Huevos 4 Materiales para la conservación de la

vivienda

10 Servicios de mantenimiento y

reparaciones

21 Servicios para el cuidado personal 21

Mantequilla y margarina 10 Servicios para la conservación de la

vivienda

10 Otros servicios relativos a los vehículos 21 Artículos para el cuidado personal 21

Aceites 10 Distribución de agua 10 Transporte por ferrocarril 10 Joyería, bisutería y relojería 21

Frutas frescas 4 Recogida de basuras, alcantarillado y

otros

10 Transporte por carretera 10 Otros artículos de uso personal 21

Frutas en conserva y frutos secos 10 Electricidad 21 Transporte aéreo 10 Servicios sociales 0

Legumbres y hortalizas frescas 4 Gas 21 Otros servicios de transporte 10 Seguros para la vivienda 0

Legumbres y hortalizas secas 4 Otros combustibles 21 Servicios postales 0 Seguros médicos 0

Legumbres y hortalizas congeladas y

en conserva

4 Muebles 21 Equipos telefónicos 21 Seguros de automóvil 0

Patatas y sus preparados 4 Otros enseres 21 Servicios telefónicos 21 Otros seguros 0

Azúcar 10 Artículos textiles para el hogar 21 Equipos de imagen y sonido 21 Servicios financieros 0

Chocolates y confituras 10 Frigoríficos, lavadoras y lavavajillas 21 Equipos fotográficos y

cinematográficos

21 Otros servicios 21

Otros productos alimenticios 10 Cocinas y hornos 21 Equipos informáticos 21

Notice that these tax rates are the result of combining the different tax rates applicable to each good contained in each category.

SOURCE: Banco de España.

DISAGGREGATION OF GOODS CONSIDERED IN THE MICROSIMULATOR AND THEIR VAT RATES IN 2015

TABLE 5

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 25 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

Table 6 shows the evolution of VAT rates in Spain from 1986. It shows that every tax

reform implemented from 1986 onwards increased VAT, with the sole exception of the one

introduced in 1993.

Table 7 compares the VAT tax rates across the EU countries. VAT rate structures vary

widely within the EU. Most countries do not have a super-reduced rate (that is, a rate below

5%), however many of them have two reduced tax rates.

13

13 9% of the total consumption of the EPF derives from goods taxed at the super-reduced rate, 31.5% at the reduce

rate, 49.2% at the standard rate and 10.4% are exempt.

Dates Reduced Rate Standard Rate

01/01/1986 6 12

01/01/1992 6 13

01/08/1992 6 15

01/01/1993 3 | 6 15

01/01/1995 4 | 7 16

01/07/2010 4 | 8 18

01/09/2012 4 | 10 21

SOURCE: European Commission.

EVOLUTION OF VAT RATES IN SPAIN TABLE 6

VAT TAX RATES BY COUNTRY TABLE 7

Member State Code Super-reduced rate Reduced rate Standard rate

Belgium

BE - 6 / 12 21

Bulgaria BG - 9 20

Czech Republic CZ - 10 / 15 21

Denmark DK - - 25

Germany DE - 7 19

Estonia EE - 9 20

Ireland IE 4.8 9 / 13,5 23

Greece EL - 6 / 13 24

Spain ES 4 10 21

France FR 2.1 5,5 / 10 20

Croatia HR - 5 / 13 25

Italy IT 4 5 / 10 22

Cyprus CY - 5 / 9 19

Latvia LV - 12 21

Lithuania LT - 5 / 9 21

Luxembourg LU 3 8 17

Hungary HU - 5 / 18 27

Malta MT - 5 / 7 18

Netherlands NL - 6 21

Austria AT - 10 / 13 20

Poland PL - 5 / 8 23

Portugal PT - 6 / 13 23

Romania RO - 5 / 9 20

Slovenia SI - 9.5 22

Slovakia SK - 10 20

Finland FI - 10 /14 24

Sweden SE - 6 / 12 25

United Kingdom

UK - 5 20

SOURCE: European Commission.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 26 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

Excise Duty Parameters

The excise duty legislation applies different taxes to each commodity. In particular, calculation

of the after-tax prices requires different types of taxes to be taken into account. Ad valorem tax

rates, like VAT tax rates, are charged as a percentage of the price. Ad quantum taxes, in

contrast, are calculated on the basis of the quantities of the good (according to the number of

cigarettes, litres of alcohol, etc.). Other excise duties considered are the Recargo de

Equivalencia (a percentage rate added to the VAT rate) and Comisión de Estanco (a retail

mark-up determined by law). The excise duties charged on each good considered are detailed

in Table 8.

SUMMARY OF GOODS SUBJECT TO EXCISE DUTIES TABLE 8

Expenditure

groups

Commodities

included

Taxes Value

Nominal market

price (a)

Tobacco

Cigarettes

Ad valorem (%) 0.51

€4.49

Ad quantum (€ per 20 cigarettes) 0.482

Recargo de equivalencia (%) 0.0175

Comisión Estanco (€) 0.09

Fine-cut

Ad valorem (%) 0.415

Ad quantum

(€ per 20 standardised cigarettes)

0.44

Recargo de equivalencia (%) 0.0175

Comisión Estanco (€) 0.085

Others

Ad valorem (%) 0.415

Ad quantum

(€ per 20 standardised cigarettes)

0.44

Recargo de equivalencia (%) 0.0175

Comisión Estanco (€) 0.085

Alcohol

Spirits

Ad quantum

(€ per litre of pure alcohol)

9.13 €12.29

Beer Ad quantum (€ per litre of beer) 0.09 €1.81

Vehicle fuels

Petrol

Estatal general

(ad quantum, cents per litre)

40.069

€122.83

Estatal especial

+ Autonómico especial

(ad quantum, cents per litre)

6.16

Diesel

Estatal general

(ad quantum, cents per liter)

30.7

€111.44

Estatal especial

+ Autonómico especial

(ad quantum, cents per litre)

6.27

Electricity Electricity Ad valorem (%) 5.11269632 €0.1526

SOURCE: Own calculations, based on Official State Gazette (BOE) and (a) AEAT annual report.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA

27

DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

Because the price information is given in terms of price indices, for the simulation of ad

quantum taxes the average market price of the good concerned is needed as a starting point.

These prices are taken from the AEAT annual report, which reports average nominal prices for

each group of goods considered in this paper, as shown in the last column of Table 8. Then, all

the taxes are deducted from these market prices in order to obtain before-tax prices. Finally,

we calculate the new after-tax prices using the post-reform tax parameters. This procedure

allows us to calculate the percentage difference between before-tax and after-tax market

prices and to extrapolate it to the price index of the corresponding good.

Each group of goods subject to excise duties has its own specific features. Tobacco is

broken down into cigarettes (cigarrillos), fine-cut tobacco (picadura) and other tobacco (puros,

cigarritos …). The formula to calculate the after-tax price is the same for all three goods:

=

(+)∗(1++)

1−∗(1++)−

where is the after-tax price, is the before-tax price (the net-of-tax price), is the ad valorem

tax rate, is the ad quantum tax rate, is the Recargo de Equivalencia, is

the Comisión de Estanco, and is the VAT tax rate. The values of the excise duties, however,

are different for the three goods, therefore there are a total of 12 excise duty parameters that

can be changed in a simulation.

Excise duties on alcohol also differ according to the product, with spirits and beer

taxed at different rates.

14

The formula to apply these taxes is the same for both goods:

=

(

+∗ℎ

)

∗(1+)

where is the after-tax price, is the before-tax price (the net-of-tax price), is the ad

quantum tax rate per litre, ℎ is the share of pure alcohol per litre of spirit (on average), and is

the VAT tax rate.

For vehicle fuels, we distinguish between diesel (gasóleo) and petrol (gasolina), which

again are subject to different excise duties, but according to the same formula:

=

(

+++

)

∗(1+)

where is the after-tax price, is the before-tax price, is the State general tax rate, is the

State specific tax rate, is the regional specific tax rate, and is the VAT

tax rate. We consider the two specific tax rates ( and ) together, as reported by the AEAT.

For electricity, in addition to the VAT,, there is only one excise duty, the ad valorem

tax, , which is applied to the price using the formula:

15

=∗

(

1+

)

∗(1+)

14 Wine is not subject to any excise duties, but only to VAT at the regular rate of 21%.

15 The law provides for a minimum tax rate of 5.11%, but in most cases the tax rate resulting from the application of the

formula below is higher.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 28 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

3.2.3 THE DEMAND SYSTEM: BEHAVIOUR IN THE BANCO DE ESPAÑA INDIRECT TAXATION

MICROSIMULATION MODEL

For the estimation of the behavioural parameters, we aggregate expenditure on the 255 goods

of the EPF into 13 groups of non-durable expenditure. We define a 14th group containing

durable expenditures, which is not included in the estimation of the demand system, but for

which total revenues are calculated. We try to group goods taking into account separability

conditions but also differences in their tax treatment. Goods subject to excise duties

(underlined below) are also included in the demand system. Notice that wine is not subject to

excise duties and electricity is included in the domestic utilities group because it has a share

that is too small for it to constitute a group on its own. The groups are:

1. Food and beverages: fresh and processed food and non-alcoholic drinks

2. Alcoholic drinks: spirits, beer and wine

3. Tobacco: cigarettes, fine-cut and others

4. Clothing and footwear: including repairs

5. Domestic utilities: water, electricity, gas, refuse collection

6. Household non-durables: including domestic services

7. Health: pharmaceutical products, dental and private medical services

8. Vehicle fuels: petrol and diesel

9. Transport: trains, buses, planes, taxis and related services

10. Communications: postal services and telephone services

11. Leisure and culture: cultural services, books, newspapers and package holidays

12. Hotels and restaurants: restaurants, hotels and other housing services

13. Other non-durables: personal care products and services, insurance and other

14. Durables: furniture and home appliances, cars, electronic equipment, private

education services and jewellery

The demand system consists of a set of 13 non-durable goods demand equations,

which are estimated jointly. We use the Quadratic Almost Ideal Demand System (QUAIDS)

introduced by Banks, Blundell, and Lewbel (1997) as an extension of the Almost Ideal Demand

System (AIDS) of Deaton and Muellbauer (1980). This is a useful demand system to evaluate

the welfare impact of tax reforms. The reason is that it allows the share of each good in total

expenditure to vary in a flexible way with respect to income and prices. In the case of income,

the good could be a luxury (elasticity greater than 1) at one level of expenditure and a necessity

(elasticity smaller than 1) at another level of expenditure. The model assumes that the utility

obtained from the consumption of any good is not affected by the labour supply of any

member of the household, except insofar as the estimated equations for each good can be

made conditional on labour supply variables.

Some goods have a high rate of zeroes because they are not consumed by the

households (not due to infrequency of purchase). For these we use a two-stage estimation

strategy. First, we estimate probit models for tobacco and domestic utilities as in equation (1).

=

+

(1)

where ℎ denotes household, is a subscript for goods ( = 1,…,), for time

( = 1,…,) and is a vector of socio-demographic variables. Then, we obtain the Mill’s

inverse probability ratios according to expressions (2) for consumers of good ( = tobacco,

vehicle fuels) and (3) for non-consumers:

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 29 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

=

(2)

=

(3)

The QUAIDS is estimated in the second stage, including the inverse Mill’s ratios as

regressors in all the equations. The demand system is based on the indirect utility function

presented in (4):

=

()

()

+()

(4)

where (), () and () are price indices defined as:

(

)

=

+

∑

+

∑∑

(5)

(

)

=

∏

(6)

(

)

=

∑

ln

(7)

where and both denote number of goods (, =1,…,). Maximising (4) subject to the

budget constraint, we can express the share of expenditure on each good , for each

household ℎ, in each period , as:

=

+

()

+

()

()

+

∑

(8)

We define

=

(

) as a function of a vector

containing a constant, socio-

demographic variables (

) and the inverse Mill’s ratio calculated in the first stage. In fact, this

involves modifying equation (5) accordingly, so that its inclusion gives rise to new adding-up

conditions that will be taken into account at the estimation stage. The resulting equation is:

(

)

=

+

∑

+

∑∑

(9)

To perform welfare analysis, we require the resulting demands to be consistent with

utility maximisation, thus satisfying theoretical adding-up, homogeneity, symmetry and

negativity restrictions. Adding-up is satisfied leaving aside one of the equations in the

estimation and homogeneity and symmetry are imposed at the estimation stage. Negativity

cannot be imposed but it can be tested for by looking at the Slustky matrix. All these

theoretical conditions limply the following linear restrictions on the parameters of the model:

Adding up:

∑

=1

;

∑

=0

;

∑

=0

for all j;

∑

=0

Homogeneity:

∑

=0

for all

Symmetry:

=

Once the model is estimated, we use the results to evaluate the impact of price

changes (following a tax reform) on consumer welfare. We do so using the associated

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 30 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

expenditure functions of the QUAIDS. We calculate the compensating variation CV. CV is

defined as the change in income a household would require to be indifferent between the

original prices and the new prices. So, if (.) is the expenditure function associated with

the model, the CV for household ℎ is:

=

(

∗

,

)

−

(

∗

,

)

(10)

∗

is the original value of utility for household ℎ,

is the price vector pre-reform and

is the

new price vector following the reform.

The results of the QUAIDS are summarised in the elasticities shown in Table 9 (shares

of expenditure, income and uncompensated own-price elasticities) and Table 10 (cross-price

elasticities). The income elasticities obtained are close to the results found in the literature using

Spanish data (Labeaga and López (1996), Labeaga and Puig (2003) or Christensen (2014)) and

even internationally (Banks, Blundell, and Lewbel (1997)). As expected, all income elasticities

are positive, and those for necessity goods such as food, domestic utilities and

communications have lower values, while those for leisure, household non-durables, and health

have the highest values. Food, tobacco, domestic utilities and communications are necessities

while clothing and footwear, household non-durables, health, leisure and culture, hotels and

restaurants and other non-durables are luxury goods. We cannot reject a unitary elasticity for

alcoholic drinks, vehicle fuels and transport. The result for health can be explained because the

survey only collects information on private expenditure on this good. Uncompensated own-

price elasticities are all negative at average values of the variables, as expected. The most

elastic goods are leisure and culture, household non-durables, transport and clothing and

footwear, while food and beverages at home are not sensitive to price changes.

OBSERVED (2015) AND PREDICTED SHARES, INCOME AND OWN-PRICE ELASTICITIES TABLE 9

Observed

shares

Predicted

shares

Income

elasticity

Uncompensated

own-price elasticity

1. Food and beverages 0.2775 0.2766 0.715*** -0.109

2. Alcoholic drinks 0.0106 0.0114 1.010*** -0.993***

3. Tobacco 0.0219 0.0221 0.846*** -0.833***

4. Clothing and footwear 0.0739 0.0759 1.385*** -1.011***

5. Domestic utilities 0.1370 0.1362 0.538*** -0.525***

6. Household non-durables 0.0402 0.0433 1.548*** -1.969***

7. Health 0.0382 0.0354 1.901*** -0.524***

8. Vehicle fuels 0.0635 0.0652 0.973*** -0.159***

9. Transport 0.0522 0.0520 0.955*** -1.090***

10. Communications 0.0511 0.0479 0.592*** -0.189***

11. Leisure and culture 0.0476 0.0478 1.421*** -2.253***

12. Hotels and restaurants 0.1254 0.1234 1.404*** -0.974***

13. Other non-durables 0.0607 0.0638 1.224*** -0.572*

* p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

SOURCE: BdE VAT Microsimulation Model.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 31 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

CROSS-PRICE ELASTICITIES TABLE 10

1.

Food and

beverages

2.

Alcoholics

drinks

3.

Tobacco

4.

Clothing

and

footwear

5.

Domestic

utilities

6.

Household

non-durables

7.

Health

8.

Vehicle fuels

9.

Transport

10.

Communications

11.

Leisure

and

culture

12.

Hotels

and

restaurants

13.

Other

non-durables

1. Food and beverages -0.109 0.02 -0.009 0.181*** 0.216*** -0.079 -0.179*** -0.224*** -0.142** 0.091** 0.170*** -0.379*** -0.272**

2. Alcoholic drinks 0.487 -0.993*** 0.104 0.256*** 0.715*** -1.959*** -0.281* -0.806*** 0.711*** 0.422** 1.852*** -0.874* -0.645

3. Tobacco -0.14 0.046 -0.833*** -0.364*** -0.106 0.456 0.556*** -0.027 0.188 0.427*** 0.117 -0.61 -0.556

4. Clothing and footwear 0.449* 0.029 -0.120* -1.011*** -0.404*** 0.076 0.042 -0.158** 0.007 -0.053 0.16 -0.462* 0.061

5. Domestic utilities 0.576*** 0.067 -0.014 -0.210*** -0.525*** 0.118 -0.577*** 0.046 0.062 -0.019 0.056 -0.377*** 0.258*

6. Household non-durables -0.784* -0.489 0.246** 0.135* 0.216 -1.969*** 0.944*** -0.176* -0.058 0.307* -1.013*** 1.468*** -0.375

7. Health -1.998*** -0.102 0.405*** 0.068 -2.356*** 1.255*** -0.524*** 1.320*** 0.253 -1.200*** 0.026 -0.252 1.203*

8. Vehicle fuels -0.925*** -0.109 -0.012 -0.136*** 0.021 -0.073 0.569*** -0.159*** -0.032 -0.145* -0.232* 0.272 -0.011

9. Transport -0.854*** 0.141 0.084 0.046 0.092 -0.022 0.180** -0.045 -1.090*** 0.210** 0.480*** -0.191 0.016

10. Communications 0.522*** 0.085 0.197*** -0.015 -0.047 0.277* -0.651*** -0.176*** 0.222** -0.189*** 0.046 -0.334** -0.530***

11. Leisure and culture 0.746*** 0.366 0.041 0.249*** 0.025 -0.816*** 0.03 -0.375*** 0.461*** 0.004 -2.253*** 1.196*** -1.095***

12. Hotels and restaurants -1.069*** -0.076 -0.131** -0.302*** -0.458*** 0.496*** -0.047 0.132** -0.103 -0.187** 0.494*** -0.974*** 0.823***

13. Other non-durables -1.594*** -0.125 -0.257*** 0.105** 0.486*** -0.277 0.713*** -0.034 0.002 -0.563*** -1.036*** 1.929*** -0.572*

* p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

SOURCE: BdE VAT Microsimulation Model.

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 32 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

3.2.4 THE OUTPUT OF THE MODEL

The model simulates the tax paid by each household (including both VAT and excise duties)

depending on its choice of consumption basket. Then, it computes and aggregates certain variables

either by income decile or by age group in order to perform some comparisons. The variables of

interest analysed are similar to those analysed in the case of the microsimulator of direct taxation:

total revenue, average tax rates, winners and losers, and several inequality measures such as the

distribution of after-tax income, Lorenz curve, Gini coefficient and some percentile ratios.

Since the microsimulator of indirect taxation allows for the behavioural responses of

households, the output of the model also includes a measure of the welfare impact of the

reform, calculated as the compensating variation for each household, that is to say

the monetary amount that a household should receive or pay to maintain its pre-reform utility in

annual terms.

16

The utility function assumed is based on Banks, Blundell, and Lewbel (1997).

Section 3.3 shows this output for two simulation exercises: first, for a change in the

VAT rate and second, for a change in excise duties.

3.2.5 THE ACCURACY OF THE MODEL

The total household expenditure on taxable goods (that is, excluding goods without price such as

narcotics or imputed rents, and goods exempt of VAT such as financial products) represented in

our dataset amounts to €350,762 million, while the AEAT reports a household expenditure on

taxable goods of €331,361 million. Our current model predicts €59,062 million of household VAT

revenues and excise duties for 2015, while the revenues reported by the AEAT amount to

€71,175 million. This difference (17.02%) could arise from the following factors. First, expenditure

measurement and reporting errors (under-reporting in the case of tobacco; infrequency of

purchase of leisure goods, for example; and individuals not represented in the survey like those in

prison, hospital, etc.). Second, and in the opposite direction, tax evasion, which could affect

expenditure on some services, maintenance, etc. And third, minor errors incurred during the

aggregation of goods into 119 groups using available price data.

The results could be adjusted to improve the prediction of total aggregated revenue.

However, since we are also interested in the distributional effects of the reform we chose not to

make these adjustments.

17

3.2.6 BASELINE RESULTS: INDIRECT TAX REVENUES AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF TAX LIABILITIES

UNDER THE 2015 LEGISLATION

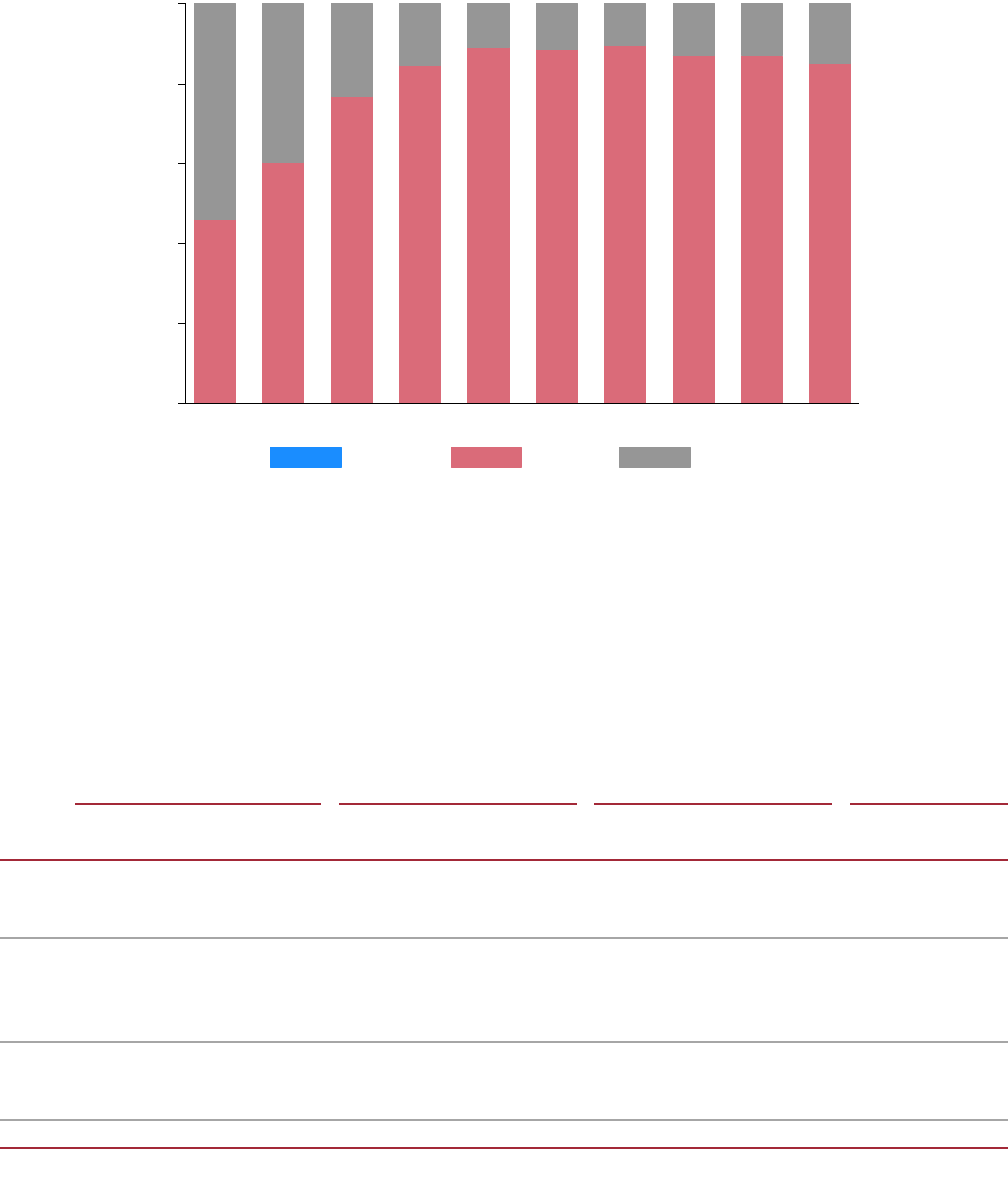

Figure 7 shows the revenue that the microsimulator predicts under the existing VAT and excise

duty legislation, disaggregated by income deciles.

18

The total revenue amounts to €59,062 million.

16 Note that, under this definition, a reform that increases a household’s welfare leads to a negative compensating

variation (the amount this household should pay back to return to its initial utility level). The output produced by the

model, however, shows the welfare gain, and therefore such a reform leads to a positive value (an increase in welfare).

17 Sources of adjustment that could be used include: Data on total consumption of vehicle fuels (except in the case of tax

evasion) provided by the Comisión Nacional de Mercados y Competencia. Data from the Comisionado de Tabacos for

tobacco, and from the Asociación de Fabricantes de Bebidas Espirituosas, Cerveceros de España and the Federación

Española del Vino for spirits, beer and wine, respectively.

18 We show the output of the microsimulator in terms joint VAT and excise duties given that each tax depends from one

another (c.f. formulae in Sectiorn 2.2.2). A microsimulator of VAT alone causes a downward bias in the estimated

baseline revenue because this amount is calculated simulating the elimination of all excise duties, and such a reform also

impacts VAT revenue downwards. Nonetheless, we have computed the total revenues and the average effective tax rate

without excise duties as a robustness check. Total revenues amounts to €45,707 million, which is an 88.93% of the VAT

revenue reported by the AEAT, and average tax rate is 11.88%, close to the one reported by Laborda et al (2016) and

Laborda et al (2017).

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 33 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

Figure 8 presents the average tax rate faced by each income decile calculated as a

percentage of income. That is, the total tax payments as a percentage of income. The tax rates in

this case decrease over the income deciles, showing that the VAT-excise duties tax is regressive.

REVENUE FROM VAT AND EXCISE DUTIES BY INCOME DECILE IN 2015 FIGURE 7

SOURCE: BdE VAT Microsimulation Model.

MEAN OF AVERAGE EFFECTIVE TAX RATE (AS % OF INCOME)

BY INCOME DECILE

FIGURE 8

SOURCE: BdE VAT Microsimulation Model.

2,441

2,900

3,774

4,462

5,038

6,158

6,418

7,340

8,958

11,573

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

Million euros

12345678910

VAT

and

Excise

Duties

Revenue

by

Income

Decile

21.69

16.71

17.33

16.61

16.08

15.92

14.37

13.85

13.82

11.99

0

5

10

15

20

12345678910

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 34 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

However, Figure 9 presents the average tax rate faced by each income decile

calculated as a percentage of consumption.

19

That is, the total tax payments as a percentage

of consumption. In this case, the tax rates are mildly flat.

The disparity in the results when the effective tax rate is computed relative to income

and relative to consumption is not new in the literature. When looking at VAT payments as a

percentage of total expenditure (as opposed to disposable income), Figari and Paulus (2012)

conclude that for five European countries (Belgium, Greece, Ireland, Hungary and the UK), the

VAT system does not seem to be regressive. Indeed, households in the richest disposable

income decile pay a higher fraction of their total expenditure on VAT than households in the

lowest income decile because they spend a higher proportion of their expenditure on goods

and services that are taxed at higher rates.

20

Given that the European Directive (2006/112/EC) of 28 November 2006 defines VAT

as “a general tax on consumption proportional to the price of the goods and services” the tax

base is the individual expenditure instead of individual income as in the PIT Microsimulation

model. Therefore, from now on, we provide average tax rates computed as a percentage of

consumption instead of income.

21

19 Notice that the denominator includes consumption on goods exempt from VAT or excise duties as is usual in the literature.

20 From a theoretical point of view, redistributing income through income tax is less costly in efficiency terms,

because it does not distort individual consumption (Atkinson and Stiglitz, 1976; Mankiw et al., 2009). That is, if the

policy objective is to tax individuals on the basis of their income, it is preferable to tax income directly, unless

consumption choices reveal something about income that cannot be captured by personal income tax (e.g. there

is significant tax evasion and under-reporting that hinders the efficient collection of income tax, and consumption

tax is less prone to evasion).

21 The IFS report for the European Commission also reports the average tax rates as a percentage of consumption when

evaluating reforms. (Adam et al., 2011).

MEAN OF AVERAGE EFFECTIVE TAX RATE (AS % OF CONSUMPTION)

BY INCOME DECILE IN 2015

FIGURE 9

SOURCE: BdE VAT Microsimulation Model.

15.22

14.78

15.15

15.40

15.36

15.60

15.64

15.71

15.82

15.57

0

5

10

15

20

25

12345678910

Mean

of

Average

Tax

Rate

(over

consumption)

by

Income

Decile

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 35 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

3.3 Simulation examples

In what follows we present two hypothetical reforms to illustrate the possibilities of the BdE VAT

Microsimulation Tool. These examples should not be understood in any way as reform

proposals of the Banco de España.

3.3.1 A CHANGE IN VAT: A ONE POINT INCREASE IN THE STANDARD VAT RATE

In the first illustrative example of the BdE VAT Microsimulation Tool we simulate a one point

increase in the VAT rate for goods taxed under the standard rate, from 21% to 22%.

Figure 10 shows the revenue change as a result of the reform, disaggregated by

income decile. The total revenue increases by €1,317 million. Revenue increases more in

the top deciles given that the richest households consume more goods and services than the

poorest one.

Figure 11 shows the winners and losers of the reform, as measured by their tax

payments. Since almost every household consumes goods taxed at the standard VAT rate,

every household loses.

REVENUE CHANGE BY INCOME DECILE FIGURE 10

SOURCE: BdE VAT Microsimulation Model.

269

201

164

142

136

111

97

82

63

52

0 100 200 300

Million euros

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 36 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

Table 11 shows the amounts behind Figure 11. For example, we can see that, among

all losers, the average loss is €72.0. Losers belonging to the bottom percentile lose €28.8 on

average, while losers belonging to the top percentile lose €147.9 on average.

Figure 12 shows that the average tax rate (as a percentage of consumption) of the

upper deciles increases most, as is to be expected from the fact that richer households spend

a larger share of their total expenditure on goods taxed at the standard rate than poorer ones.

WINNERS AND LOSERS FIGURE 11

SOURCE: BdE VAT Microsimulation Model

WINNERS AND LOSERS TABLE 11

Total Winners Losers Neutral

Deciles Population

Gain (+) or

loss (-)

Avg. gain

or loss

Number % Avg. gain Number % Avg loss Number %

millions million € € millions € millions € millions

1 1.8 -52 -28.5 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.8 99.0 28.8 0.0 1.0

2 1.8 -63 -34.3 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.8 100.0 34.3 0.0 0.0

3 1.8 -82 -45.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.8 100.0 45.1 0.0 0.0

4 1.8 -97 -53.2 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.8 100.0 53.2 0.0 0.0

5 1.8 -111 -60.6 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.8 100.0 60.6 0.0 0.0

6 1.9 -136 -73.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.9 100.0 73.1 0.0 0.0

7 1.8 -142 -79.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.8 100.0 79.0 0.0 0.0

8 1.8 -164 -89.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.8 100.0 89.1 0.0 0.0

9 1.8 -201 -109.4 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.8 100.0 109.4 0.0 0.0

10 1.8 -269 -147.9 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.8 100.0 147.9 0.0 0.0

Total 18.3 -1,317 -72.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 18.3 99.9 72.0 0.0 0.1

SOURCE: BdE VAT Microsimulation Model.

0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1

12345678910

yy

Winners Losers Neutrals

BANCO DE ESPAÑA 37 DOCUMENTO OCASIONAL N.º 1707

With regard to welfare changes, Figure 13 shows that all deciles of income experience