Creating a Cool Japan:

Nationalism in 21

st

Century Japanese Animation and Manga

Majesty Kayla Zander

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the

Prerequisite for Honors

in Japanese Language and Culture

under the advisement of Robert Goree

May 2021

© 2021 Majesty Zander

1

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ...........................................................................................................................1

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................2

Introduction ....................................................................................................................................3

Chapter 1: Cool Japan...................................................................................................................8

Cool Japan and Nationalism ..................................................................................................................... 8

Cool Japan and Anime ............................................................................................................................ 16

Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 19

Chapter 2: Clean Japan ..............................................................................................................22

Clean Japan and Nihonjinron .................................................................................................................. 22

Clean Japan and Media ........................................................................................................................... 25

Clean Japan and Anime ........................................................................................................................... 27

Clean Japan and Anime: Hetalia ........................................................................................................ 32

A Clean Japan ................................................................................................................................. 34

Tsukkomi as Japaneseness ................................................................................................................ 35

Taiwan: Asia-yearning-for-Japan ..................................................................................................... 37

Korea as a Foil ................................................................................................................................ 41

Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 46

Chapter 3: Controversial Japan .................................................................................................48

Controversial Japan and Nationalism...................................................................................................... 48

Controversial Japan and Anime: Code Geass ......................................................................................... 56

Controversial Japan and Anime: GATE .................................................................................................. 61

Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 69

Conclusion ....................................................................................................................................71

Works Cited ..................................................................................................................................74

2

Acknowledgments

I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Robert Goree, for his endless patience and

guidance. Thank you for never giving up on this thesis project, despite my year-long battle with

procrastination. I cannot express how much your patience, kindness, and understanding has

contributed to the completion of this thesis. From the bottom of my heart, thank you.

I would also like to thank Yoshimi Maeno, my major advisor, for four years of support

and encouragement. I will never, ever forget your kindness and enthusiasm both inside and

outside of the classroom. Thank you so much for everything.

I would like to thank Eve Zimmerman for all her support and care since my sophomore

year. Thank you so much for the years of advice and guidance as I completed my major in the

EALC department. I loved all of your courses and wish I could have taken more.

To the remaining members of my thesis committee: thank you so much. Thank you,

Angela Carpenter, for years of patience and kindness. I hope to be as eloquent and graceful as

you one day. Thank you, Sun Hee Lee, for agreeing to be a part of this process and for your

kindness.

Next, I would like to thank a different Robert—Daddy, I love you. Thank you for going

out of your comfort zone and watching anime just to spend some time with your kids. Thank you

for the sacrifices you have made in order for me to complete my degree at Wellesley and pursue

what I love. Mommy, thank you for never doubting that I would finish this project and thank you

for taking me back and forth to work, listening to music with me in the car, and watching all the

seasons of Produce 101 with me in the summer. I love you.

I would like to thank all my friends for giving me a space to just be myself. Emma,

Maggie, Midori, Nafisa, thank you for always encouraging me and sending me love when it felt

like finishing was impossible. Jayli, this is probably the last time I will get to say it, so thank you

for introducing me to anime. I love you more than you will ever know. Kendalle, thank you for

listening to me rant and panic over my thesis deadlines for 8 months. I love you so, so much.

I would like to thank Shannon Mewes, whose amazing Ruhlman presentation inspired me

to pursue an anime-related thesis.

Lastly, I would like to thank my stubbornness for not allowing me to give up and my 3am

playlist that got me through the longest nights.

3

Introduction

In most scholarship examining the history of Japanese anime, Tezuka Osamu is credited

with pioneering the modern age of anime and manga.

1

While the origins of anime can be traced

to the early 1910s, it was Tezuka’s work during the 1950s and 1960s that influenced an entire

generation of aspiring Japanese animators and artists.

As his techniques transformed into industry

standards, numerous artists began expanding upon

the themes featured in Tezuka’s works, leading to

the development of well-known subgenres such as

mahō shōjo (magical girl), mecha (giant robots), and

ecchi (playful erotica) during the 70s and 80s.

Although series such as Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) and Magical Princess Minky Momo

(1982) enjoyed domestic success, few modern anime made their way to Western screens prior to

the late 1980s. In 1989, the positive reception of Otomo Kasuhiro’s film Akira (1988) in North

America indicated there was hope for a Western market in the anime industry, despite earlier

licensing failures. Following a series of hit-and-miss distribution attempts during the early 1990s,

anime suddenly gained a strong foothold in the West with the success of Sailor Moon (1992),

Dragon Ball Z (1989), and Evangelion (1995). From 1995 to 1997, each anime introduced

American audiences to a different genre targeted at a specific audience (mahō shōjo for young

girls, shōnen for young boys, and mecha/seinen for older men, respectively). Their popularity

and marketability in the West soon made the three series symbols of the 90s anime boom.

1

Manga (Japanese comic books/graphic novels) are commonly used as source material for anime (Japanese

cartoons/animations).

Figure 1: Tsukino Usagi from Sailor Moon

4

Western interest in Japanese media did not stop at anime either, as video games and multimedia

franchises like Pokémon and Yu-gi-oh also became well-known during the 1990s.

As anime became more popular in the West, viewer

interaction with the medium also began to evolve. The 90s

saw the first American anime conventions, the beginnings of

cosplay (costume play) culture, and the rise of fan-produced

translations of anime and manga in the West. In 2002,

Douglas McGray published an article titled “Japan’s Gross

National Cool,” which outlined the Japanese government’s

failure to take advantage of growing international interest in

their cultural exports (53). At the time of the article’s release,

the anime industry was worth about 22.4 billion yen (203

million USD) outside of Japan (The Association of Japanese Animations, 2013). Within three

years, that number had grown to 31.3 billion (284 million USD) (AJA, 2013). While these

profitability figures take into account the work of official licensing agencies that made anime

more accessible to Western audiences, they are

not reflective of the free fan-produced content

that dominated the internet and greatly boosted

anime’s popularity during the 2000s.

Although Western companies such as

Funimation and Viz Media were acquiring the

rights to dub and distribute an increasing

number of anime each year, keeping up with

Figure 2: Promotional poster for

AnimeCon '91

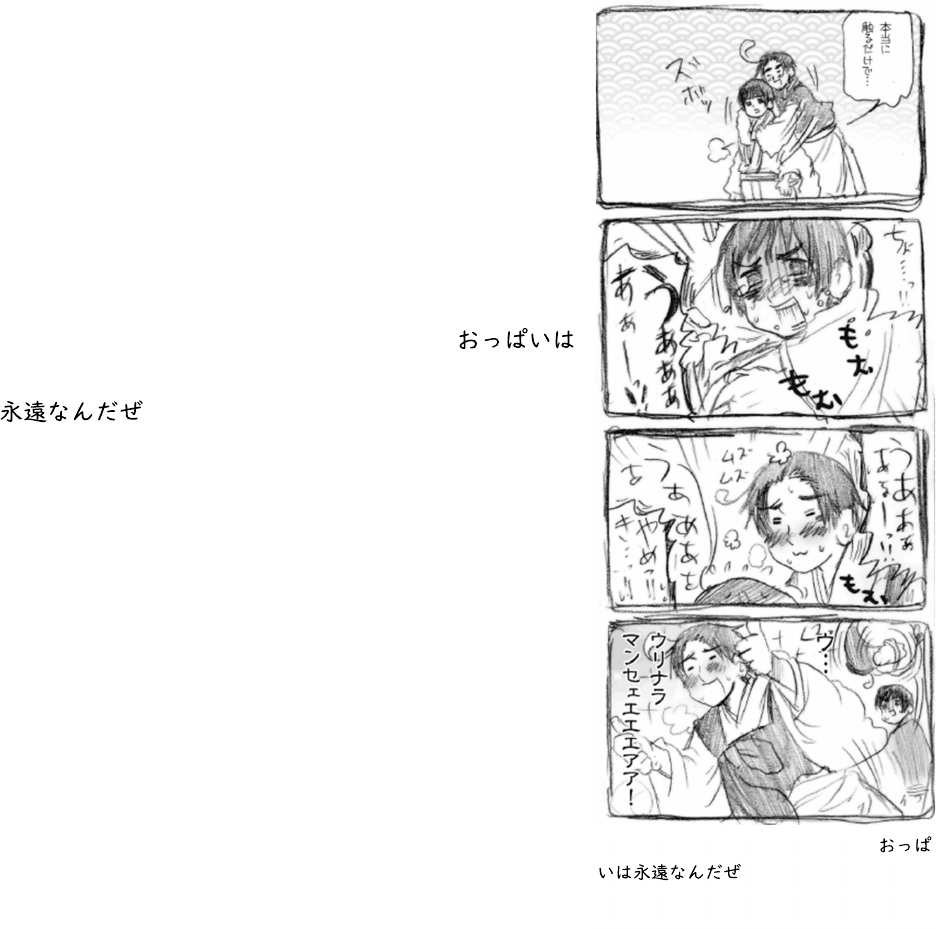

Figure 3: Example of fansubs with a translator's note from

Luck Star (2007)

5

the growing demand, especially for lesser-known anime to be licensed, proved nearly impossible.

Taking matters into their own hands, piracy and fan-made translations, or “fansubs,” became

prevalent in the international anime community throughout the 2000s and 2010s. Novices and

professionals alike would often form fansub groups or teams to translate, edit, typeset, time, and

encode various series to release to fans, free of charge. Due to the independent nature of

fansubbing and the lack of copyright laws on video-sharing websites like YouTube, Western fans

were given access to a much larger variety of anime during this period. Despite distributors

losing direct profit from the pirated content, ease of accessibility and increased prevalence

continued to boost anime’s popularity overseas. The mid to late 2010s saw the decline of English

fansubs, as copyright laws became more strict and licensing companies such as Crunchyroll and

Funimation began releasing subtitled and dubbed anime at an increased pace. While this

transition entailed new paywalls such as pay-per-view or monthly subscriptions, the subsequent

rise of multi-device streaming meant that almost anyone with a device could now access

thousands of anime legally, at a single touch.

Although the 1990s served as an integral period of growth for the anime industry, the

same could not be said for other sectors of the Japanese economy such as finance, real estate, and

the stock market. After the burst of its bubble economy in 1991, Japan suffered from a prolonged

period of economic stagnation and unemployment. This period, referred to as the “Lost Decade,”

is often cited as ending in 2001, despite its ongoing impact on the Japanese economy. As such,

prior to 2001, government officials lacked the time and resources to focus on boosting

international interest in Japanese cultural assets. While McGray’s concept of “national cool” and

the term “cool Japan” began gaining traction in 2003, it was not until 2010 that the Japanese

6

Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) began laying the groundwork for what would

become the “Cool Japan Initiative.”

When the Cool Japan Initiative officially launched in 2013, it featured anime and manga

as a creative industry that would aid its goal to improve Japan’s image internationally and boost

the economy through foreign consumption. Despite the initiative’s underperformance, the anime

industry grossed an all-time high of 60.3 billion yen (550 million USD) outside of Japan in 2018

(AJA, 2019). Over the past eight years, the anime industry has flourished overseas, both

culturally and economically. While anime may strike some as childish entertainment, to others it

has become a gateway to understanding Japanese culture. As anime and manga continue to gain

popularity, their influence on the way international audiences view and interact with Japan will

continue to grow and change as well. This is why it has become increasingly important to

analyze exactly what messages anime and manga creators convey to their audiences.

Among the thousands of anime released each year, many tackle deeper themes and topics

such as social inequality, technologization, and militarism. One such topic that I have noticed

appearing more frequently is nationalism. From the anime I watched as a child to my most

recently read manga, I have discovered nationalism sprinkled throughout the stories, hidden in

the punchline of a joke or boldly present in the characters’ ambitions. In an attempt to explain or

provide context for the nationalism I have found in modern anime, this thesis will explore three

frameworks through which nationalism is presented and examine what purpose the indications of

nationalism serve. The frameworks are “Cool Japan,” “Clean Japan,” and “Controversial Japan.”

Chapter 1 will examine the role of cultural nationalism in post-war Japan and the

Japanese government’s attempts to monetize cultural nationalism and improve Japan’s image

through METI’s “Cool Japan Initiative.” This chapter will also examine how Cool Japan is used

7

in anime to encourage foreigners to engage with Japanese culture. Chapter 2 will discuss Clean

Japan, a self-coined expression used to describe the dissemination of self-applauding stereotypes

through Japanese media. I will discuss what ideologies form the basis of Clean Japan and how

they are used in Japanese media today. I will use examples from three anime and manga series to

demonstrate how Clean Japan manifests itself in anime and what purpose it serves in both the

context of the series and the real world.

Chapter 3 will examine Controversial Japan, another self-coined term that describes

displays of Japanese imperialism and militarization in Japanese media. I will examine the

relationship between neonationalism, Japanese youth, and nationalistic anime before discussing

two anime series that justify or support militarization by featuring Japanese characters defending

their land from an invading enemy and attempting to improve the quality of life for oppressed

peoples. My conclusion will seek to explain where I believe nationalism in anime may be headed

and my thoughts on the future of the Cool Japan Initiative and the anime industry.

8

Chapter 1: Cool Japan

The first nationalist framework I will examine is “Cool Japan.” Within the context of this

thesis, Cool Japan (derived from METI’s Cool Japan Initiative) describes soft cultural

nationalism found in Japanese media. As its name implies, the purpose of Cool Japan is to

market the “coolness” of Japanese culture to domestic and international audiences. By increasing

the popularity of the country’s cultural exports, the Japanese government hopes that Cool Japan

will aid in stimulating the economy and improving the reputation of its nation and culture.

However, Cool Japan can also serve as a stepping-stone to a larger, much more complex web of

cultural nationalism present in Japanese media.

In this chapter, I will begin by defining cultural nationalism and provide a brief overview

of government initiatives to promote Japanese culture prior to the launch of the Cool Japan

Initiative. Next, I will examine the current progress of the Cool Japan Initiative before

contextualizing the anime industry’s role within Cool Japan.

Cool Japan and Nationalism

Before examining the METI’s Cool Japan Initiative, I would like to elaborate on the

terms “nationalism” and “cultural nationalism.” Merriam-Webster provides a simple definition

of nationalism as “loyalty and devotion to a nation; especially a sense of national consciousness.”

The French Marxist Louis Althusser defined nationalism as an “imaginary transposition of [one’s]

real conditions'' used to “represent to [oneself] their real conditions of existence” (163). Along a

similar line of thought, Harootunian defines it as an “aspiration of a group or class” that

combines with the tangible expression of an individual to form an “imaginary universe” that

exists “among other universes in any given age” (59).

9

All three definitions acknowledge that nationalism exists as an imaginary concept, often

created and manipulated by the state. This concept serves as a nexus of idealized views of

oneself, or the nation, that one hopes to manifest in reality. In order for a single individual to

transpose themself onto the image of the nation, there first has to be a clear sense of “nation.” It

is possible to construct this sense of nation through the establishment of a defined culture, which

gives rise to “cultural nationalism.”

Cultural nationalism can be defined as “a form of nationalism in which the nation is

defined by shared culture.” This definition requires both a set idea of what makes up the culture

and methods to distinguish who belongs to it. Additionally, highlighting the differences between

those within and outside of the culture functions to strengthen the notion of “us” as one united

group. If this group, now wielding a sense of distinctiveness, is able to reach political

legitimization (i.e. by demarcating their territory), then they can become what is commonly

recognized as a nation.

The introduction of nationalism, or the “imaginary universe,” into a society can aid the

development of community, pride, self-identity, power, and wealth. Under state control,

nationalism can also serve as an instrument to indoctrinate and mobilize the people. Althusser

argues that Ideological State Apparatuses (ISA), defined as state apparatuses used to spread

ideology of the state, manifest themselves in different private domains (145). ISAs can function

either through the direct control of the state or through the government’s close monitoring of

nationalistic material created by the people. Althusser argues that two closely intertwined ISAs

are the “communications ISA” (the press, radio, and television) and the “cultural ISA'' (literature,

the arts, and sports). He states that both the ISAs “[cram] every ‘citizen’ with daily doses of

nationalism, chauvinism, liberalism, moralism, etc” (154). One of the reasons I have chosen to

10

focus on anime in this thesis is because the medium allows citizens to give the imaginary

universe visual form in the present. Unlike live-action media that is constricted by its use of real

people and places, anything is possible in animation. Any past or future a creator envisions can

be shown through their work and spread among the people, making anime and manga prime

ISAs.

ISAs are important to the state because they are able to penetrate the private lives of

citizens without immediately raising alarm. In the 50 years since Althusser made his argument,

globalization and technological advances have elevated the role of mass media as a key tool of

the state. As a result of these changes, through our screens we can connect to almost every corner

of the globe. This increased contact with various cultures has been used to both highlight the

differences between our societies and strengthen a sense of unity between shared groups. In the

1950s, Japan began its long path to regaining its diplomatic status and constructing a new sense

of identity for Japanese citizens.

During the U.S.-led Allied Occupation from 1945 to 1952, Japan was forced to rebuild

almost every sector of its society. It was during this period of reconstruction that the Japanese

government began contemplating how the nation could improve its reputation with the countries

it had colonized and fought against during World War II. Effectively defanged through the

stripping of their military and monarchical power, government officials were left with little

choice but to establish Japan’s new image as a peaceful country, changed from the horror of the

atomic bombs and devoted to promoting harmony. Japan’s period of reconciliation and reflection

during the 50s and 60s manifested in many different ways, from diplomatic apologies and

reparation negotiations to the construction of structures such as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial

Museum.

11

Japan’s first large-scale opportunity to rebrand itself

to the world came during the 1964 Olympics. It had been 19

years since Japan’s unconditional surrender and the country

now had a grand stage to present itself as a modern, peace-

loving nation and validate the work it had put in over the past

12 years. Millions of dollars were poured into the

construction of new infrastructure in and around central

Tokyo. During the same period, architects were tasked with

creating symbolic statues and buildings to be used in

ceremonies commemorating those lost during the war.

Cultural landmarks like the Nippon Budokan, Tokaido bullet

train, and the beginnings of modern

Harajuku and Shibuya were all born out of

the preparation and impact of the Tokyo

Olympics (Tagsold 299).

2

Perhaps more important than the

upgraded infrastructure, the Olympics

provided the Japanese with a “pure” form

of nationalism that was devoid of ultranationalistic overtones (Abel 148). After the war, Japanese

citizens experienced a period when it was difficult to publicly display support for their country,

as the flag and national anthem were still associated with the atrocities of the Pacific Theater.

However, Japan’s role of host nation and the spectacle of the Olympics meant that Japanese

2

Harajuku and Shibuya were located next to the “Olympic Village” where foreign athletes and press stayed during

the Olympics. The fancy new shops, renovated train stations, and foreign crowds attracted many Japanese residents

to the area, marking the beginning of Harajuku and Shibuya being seen as cool or trendy areas.

Figure 4: The Nippon Budokan under

construction in 1964.

Figure 5: Sakai Yoshinori carrying the Olympic Torch at the

Opening Ceremony in Tokyo.

12

citizens were free to openly cheer for their athletes and national symbols without international

scrutiny. Despite widespread concerns regarding Japan’s ability to showcase itself properly (both

as competitors and as a nation), the Tokyo Olympics were an all-around success. Japan not only

effectively reintroduced itself to the world, but also improved its political and economic

reputation and finished with the third highest medal count, lagging behind only America and the

Soviet Union (Abel 165).

The Japanese government took advantage of the international attention generated by the

Olympics to promote various Japanese goods, such as cameras, meters, and other mechanical

products (Abel 153). This served as the groundwork for Japan’s automobile boom in the 70s and

the electronics boom through the 80s and 90s. While these upsurges provided a major boost to

the economy, it became increasingly apparent that in order to boost Japan's cultural reputation,

the government would need to promote Japan’s cultural exports. Although technological exports

were known to be Japanese, they lacked cultural significance.

3

Although the term “Cool Japan” originates from McGray’s “Japan’s Gross National

Cool,” Asia’s first taste of a cool, post-war Japan was during the 1980s. Iwabuchi Koichi argues

that the 1983 NHK drama, Oshin

4

laid the foundation for Japan’s modern soft power initiatives.

The Japanese government took the popular drama and exported it (usually for free) to over 60

countries across Asia, North America, and South America in hopes that viewers’ opinions on

Japan would change as they followed the titular character, Oshin, from her Meiji-era childhood

to her late Showa years. The soap opera’s overwhelmingly positive reception prompted

3

Many companies intentionally changed the names or logos of their exported products to minimize their association

with Japan, since opinions on the quality of their products were still mixed in the West.

4

Oshin is a Japanese serial drama that originally ran from 1983 to 1984. The story is told as a series of flashbacks as

Tanokura Shin, also known as Oshin, recalls different periods of her life from childhood to old age. As the series

progresses, audiences are introduced to a number of different regions of Japan and historical eras that Oshin lived

through.

13

discussion among Japanese officials and scholars regarding whether television programs could

become a viable tool in “disseminating a humane image of Japan in the world” (Iwabuchi 75).

Despite persisting tensions with its East Asian neighbors, Japan was able to effectively

rebrand itself, carrying its persona of a harmonious nation into the 21st century. In 2004, Japan’s

Cabinet Office released a report stating that the “spirit of wa and coexistence” would form the

backbone of Japan’s diplomacy, with wa being defined as “a distinct Japanese concept meaning

harmony, peace, fusion, and consideration of others” (Bukh 473). Concepts such as wa and

awase (to match; to combine) are further promoted through the Cool Japan Proposal and its

subsequent guides to Japanese culture.

As mentioned in the introduction, the Cool Japan

Initiative (from here on out, the Initiative) is an initiative

created by the Japanese government in order to boost the

Japanese economy and improve Japan’s reputation through

the promotion of Japan’s cultural industries. Planning for the

Initiative ran from late 2010 to 2012, before being launched

in 2013. METI’s goals for the Initiative included acquiring

8-11 trillion yen in the global marketplace, increasing

international interest in Japan, rebranding Japan’s post-war

image among Asian countries, and rekindling domestic interest in Japanese culture. In order to

do this, the Initiative designated various “creative industries” that would be eligible to receive

government funding and promotion. As of 2014, these industries include:

Advertising, architecture, art and antiques, crafts, design, fashion, movies and videos,

video games, music, performing arts, publishing, computer software and services, radio

and television, plus furniture, tableware, jewelry, stationery, food products, tourism.

(Cool Japan Strategy 8)

Figure 6: Promotional poster for Oshin

14

Similar to the Tokyo Olympics, the Initiative also has multifaceted goals, especially

regarding its portrayal of Japan to different audiences. Broadly speaking, the Initiative has three

main target audiences: Japanese youth, citizens of neighboring Asian countries, and potential

tourists (especially those from the West). “Raised on Disney” and lacking “awareness of [their]

own cultural structure,” Japanese teenagers and young adults are seen as untapped wells of

economic stimulus for the Initiative’s creative industries (Hambleton 36, Editorial Engineering

Laboratory 3). Through government-funded programming and the promotion of domestic

tourism and consumerism, the Initiative has marketed traditional arts and local goods as

authentic and engaging to Japanese youth, dubbing them “the Original Cool Japan” (EEL 4).

However, the Initiative has had mixed reception in Japan with opinions ranging from optimistic

to “a downward spiral of wasted tax money” (SoraNews24).

Japan has adopted a somewhat contradictory approach when marketing itself to Asia.

Seemingly unable or unwilling to move past the historical pattern of distancing themselves from

the Asian continent, Japan has used various media to arouse feelings of “cultural

superiority...camouflaged by apparent cultural commonality” (Iwabuchi 67). This concept will

come up again in Chapter 2, but from their first contact with China during ancient times, Japan

has oscillated between asserting its commonality and its differences from the rest of Asia. These

shifts are almost always politically motivated—the Initiative itself serving as a prime example. In

Japanese media, cultural commonality is used to encourage Asian audiences to watch Japanese

media under the pretense that Japanese programs are easier to understand and relate to than

Western media. However, the same media being marketed for its mutual Asianness contains

subtle assertions of cultural superiority.

15

Since the shared cultural strategy cannot be applied to non-Asian audiences, the Initiative

has adopted a mouse-and-cheese model, which is outlined extensively in the Cool Japan Strategy.

The model assumes that if Japan can prove its cultural coolness, foreigners will eventually

contribute to the domestic market through tourism and spread the good word once they return

home. The Initiative has also attempted using flattery to entice foreigner audiences, stating in

official reference material for Cool Japan that foreigners are “the key to revitalizing Japan” and

that “the respect for ‘visiting gods’ embedded in culture also explains why Japanese people treat

gaijin (foreigners) and imported goods with such deference” (EEL 11).

Eight years have passed since the Initiative was launched, but determining its level of

success has been complicated. Considering the current visibility and prevalence of Japanese

culture internationally, Japan’s soft power has increased since 2013. However, when comparing

Japan’s growth to that of South Korea’s during the same time frame, most would agree that

Japan’s accomplishments fall flat. While it is fair to say that the Initiative is working, it has taken

much more time than initially anticipated to gain results. Even then, it is sometimes difficult to

prove that Japan’s growth can be directly attributed to Initiative ventures.

Recurring diplomatic issues have also hindered the Initiative's goal to improve Japan’s

political reputation in East Asia. Repelled by the Trump administration’s volatile trade war with

China, Sino-Japanese relations have improved dramatically as the two countries have increased

economic and diplomatic cooperation, even throughout the COVID-19 crisis. With Korea,

however, tensions over World War II comfort women and forced laborers have flared

periodically from 2015 to 2021. Unresolved disputes and subsequent boycotts of Japanese brands

and products have dampened Japan’s efforts to enhance their reputation in South Korea.

16

Furthermore, the Initiative has suffered several economic failures due to a combination of

poor investment choices, project mismanagement, and lackluster execution. As of 2017, the

Initiative has lost a total of 4.4 billion yen (40 million USD) in government and taxpayer funding

(Harano 4). When reports were released in 2017 detailing the failures of several Initiative-funded

projects, officials were met with harsh criticism from business analysts and citizens alike.

Eventually this criticism reached the Western press, leading to a string of articles from 2018 to

2019 that decisively labeled the Initiative as a failure. Nevertheless, the Cool Japan Fund has

committed to continued investment in domestic and international projects throughout the 2020s,

including those within the anime industry.

Cool Japan and Anime

Steven Green argues that the Initiative is similar to a 1960s strategy in which Japanese

government officials would choose “winning” industries to “promote and protect” (59). It is a

testament to the anime industry’s growth that it has received government recognition and funding

in spite of its humble origins as children’s entertainment. As stated in the introduction, anime

enjoyed an international boom during the 1990s which birthed a subculture in the West. By the

late 2000s, anime subculture began garnering international attention for its size and staying

power. Although Japanese people were aware of anime’s growing popularity in the West, during

the 1990s scholars began to debate whether or not anime was capable of properly representing

Japanese culture to the world.

Some Japanese scholars were enthusiastic about anime’s explosive popularity and the

interest it had generated in the West. They felt that the emergence of these fans marked the

beginning of a new era in Japanese soft power and that more effort should be put into utilizing

17

anime and similar media to increase Japan’s influence. However, opposing scholars argued that

anime was not an adequate source of soft power due to its mukokuseki (nationless) nature

(Iwabuchi 31, 34). Not limited to animation, mukokuseki was used to describe a number of

products and mediums that originated from Japan, but lacked distinct Japanese character. When

discussing anime, there are two facets of mukokuseki: visual and societal. Visually, many anime

characters are not drawn resembling any one race. Although they speak Japanese, they often

have ambiguous features or unnatural coloring, which leaves viewers with something of a blank-

slate to interpret the character’s races any way they would like. This aspect of interpretation can

diminish cultural nuances, but allows easier consumption of the foreign works. Societal

mukokuseki, on the other hand, is present in anime that are not set in Japan at all or feature a

version of Japan that lacks distinct aspects of Japanese culture or vastly simplifies them. Both

forms of mukokuseki generate so much criticism because once the cultural and societal nuances

have been stripped from the work (assuming that they were present to begin with), it becomes

difficult to expect foreign fans to grasp and gain interest in Japan’s complex society in the real

world.

Nevertheless, I believe that mukokuseki functions well as a gateway to ease viewers into

Japanese culture. While it would be difficult to argue that watching Dragon Ball Z will teach

audiences all about the real lives of Japanese citizens, it can serve a segue—either to anime that

are more reflective of reality or to a general interest in learning more about Japan. One could

argue that this concept of gateway mukokuseki has already been affirmed through the Initiative’s

inclusion of anime and manga in its official plans and the adoption of its mouse-and-cheese

model.

18

In a sense, it is precisely because of anime’s mukokuseki nature that it is able to fit into

the Initiative’s strategy. Despite the characters’ ambiguous racial features, more often than not,

the world anime characters live in is either outright stated to be Japan or heavily imbued with

Japanese customs and values. When Iwabuchi discusses mukokuseki, he is speaking about a

period when the most popular Japanese games and anime were those that lacked a distinct sense

of Japaneseness. However, now thousands of new anime have been released, many of which

cannot function without Japan at the center of the series. I consider these anime to be “inward-

facing,” as they center on Japan’s past or rely heavily on Japanese history, traditional culture,

and ideals. For example, Noragami (2014) tells the story of middle school student, Iki Hiyori,

who gains the ability to interact with spirits and kamigami (Shinto gods) after nearly being hit by

a bus. Although inward-facing anime tend to have a learning curve, they can also serve as a form

of pedagogical entertainment that introduces foreign audiences to traditional Japanese literature,

history, religion, and mythology (e.g. fans of Noragami who are not familiar with Japanese

mythology can learn about various gods, folktales, and key concepts of Shinto simply by

watching the series).

Conversely, there are also “outward-facing” anime, or anime that usually focus on the

present and future of Japan and other nations, that tend to contain more conventional attributes of

mukokuseki. However, while mukokuseki anime are almost always outward-facing, outward-

facing anime are not always mukokuseki. Some outward-facing anime, such as Kaze ga Tsuyoku

Fuiteiru (2018)

5

and Banana Fish (2018)

6

, might give characters specific ethnicities and

5

Kaze ga Tsuyoku Fuiteiru, or Run with the Wind, is a 2018 sports anime, based on the 2006 novel of the same

name written by Miura Shion. The story follows 10 college dorm mates as they are unknowingly enrolled into their

college’s track and field team by their RA and team captain, Haiji Kiyose. Despite their varying levels of physical

fitness and athletic background, Haiji has high hopes for the team as they train to race in the prestigious Hakone

Ekiden.

6

Banana Fish is a 2018 mixed-genre anime, based on the 1985 manga by Yoshida Akimi. Majority of the story

takes place in New York City as Japanese college student Okumura Eiji and his photojournal boss begin covering a

19

nationalities or it might be central to the plot that the story is not set in Japan. This is why

outward-facing anime set in the present or near future may seem more realistic. Because

outward-facing media accepts the current state of Japan and its history up until now, it can teach

viewers Japanese humor, daily life, business culture, school life, sports culture, fashion,

architecture, industries, etc. There are even shows like Shirobako (2014), an anime about the

anime industry and the production of anime adaptations, which are made with the express

purpose of teaching their audiences.

That is not to say that there can be no overlap between inward and outward-facing media.

Gintama (2006) is a wonderful example of anime that mixes Japanese history and traditional

values with modern culture. While Gintama is well-known for frequently breaking the fourth

wall with its pop culture references and outlandish gags, the story itself is set in the Bakumatsu

period of Edo Japan and many of its characters are based on historical figures from groups such

as the Shinsengumi

7

and Kiheitai

8

.

9

Although there are many visually defined mukokuseki

characters, the story cannot function without the knowledge that the characters in question are

Japanese.

Conclusion

Examining the financial growth of the anime industry can also shed light on its overall

development and its role within the Initiative. As of November 2020, the Cool Japan Fund has

spent 105.6 billion yen (1.05 billion USD) on 48 investment projects in various fields. Of this

105.6 billion yen, 5.05 billion (505 million USD) has gone into media projects, which includes

story on street gangs in America. During the interview process, Eiji meets Ash Lynx, a teenage gang leader, and is

quickly caught up in the mystery and violence that surrounds Ash’s life.

7

The special police force of the Tokugawa shogunate from 1863-1869.

8

A famous volunteer militia that fought against pro-government groups from 1863-1868

9

The final 15 years of the Tokugawa shogunate during the Edo period, just preceding the beginning of Japanese

modernization.

20

anime. Some examples of foreign investments include a three-year 1.5 billion yen (14 million

USD) grant given to Tokyo Otaku Mode (2014-2017), an online anime merchandise company,

and 3.3 billion yen (30 million USD) in funding to Sentai Filmworks, an American licensing and

distribution company, in 2019. From 2014 to 2019, the anime industry grossed 9.8 trillion yen

(92 billion USD) world-wide. In the Japanese market alone, it has grossed over 1.1 trillion yen

(10 billion USD), with 2.17% (213 billion yen, or ~2 billion USD) originating from overseas

sales. As of 2019, the global anime industry has reached a value of 2.6 trillion yen (24 billion

USD). Although these stand-alone numbers have fallen short of the 8-11 trillion yen (73-101

billion USD) goal outlined in the Cool Japan Strategy, they are impressive in their own right and

indicative of the industry’s rapid expansion.

However, with rapid expansion comes the rapid change of every corner of the industry.

Within the last 5-6 years, the growing economic value of the anime industry has resulted in more

anime being released faster than ever before. We appear to be in an age when, with enough luck

and talent, anyone can become a mangaka (manga author/illustrator) or light novel author and

have their work adapted into an anime. As the number of stories being told increases, so does the

number of anime and manga that deal heavily with nationalism and associated themes. While

there has been extensive discussion and scholarship written in regards to nationalism in Japanese

media, relatively few have homed in on the nationalistic themes present in modern anime. I have

chosen to discuss anime specifically in this thesis both because it is of personal interest to me as

a long-time fan of anime and because I believe that anime should receive more individual

attention from present scholars, rather than being dissolved under the broad umbrella of “media.”

Today, anime is reaching more audiences than previously thought possible and it is critical that

viewers begin thinking about exactly what they are being shown and why. While that process of

21

critical thinking should begin at examining Cool Japan and its purpose within anime and manga,

it certainly should not end there. Although some series contain elements of Cool Japan and soft

cultural nationalism that are only meant to attract audiences, other series use Cool Japan as a

gateway to express deeper motives that stem from less innocuous forms of cultural nationalism.

22

Chapter 2: Clean Japan

If Cool Japan’s role is to show how cool Japanese culture is, then Clean Japan’s role is to

transform that coolness into admiration. Clean Japan is a term I will use to describe positive,

self-serving Japanese stereotypes present in Japanese media. These stereotypes often suggest that

the Japanese are naturally cleanly, polite, calm, virtuous, orderly, hard-working, and peaceful.

Clean Japan also promotes the idea that Japan is an extremely safe, peaceful country.

10

Whenever unruly characters appear or dangerous events are shown on screen, Clean Japan

ensures that they are clearly labeled as rare occurrences. Although Clean Japan’s start was

limited to Japanese audiences, as Japanese media has spread across the globe, a growing number

of international viewers are now being exposed to these stereotypes and tropes. In this chapter I

will explain the relationship between Clean Japan and the post-war nihonjinron movement

before analyzing the media’s role in Clean Japan. I will then give examples of Clean Japan found

in three anime released from 2009 to 2018 with a sustained discussion of Hetalia: Axis Powers.

Finally, I will examine Clean Japan in relation to the Cool Japan Initiative and the third

framework, Controversial Japan.

Clean Japan and Nihonjinron

Clean Japan stems from: a) nationalistic conceptions the Japanese had about themselves

prior to World War II and b) post-war Japan’s new image that was created by the Japanese

government. During the height of Japanese imperialism in the early 1940s, Japanese ideas on

identity were inseparable from the state. Since 1890, the dominant view on identity in Japan was

10

I would like to clarify that my focus on Clean Japan in this chapter is not meant to insinuate that Japan is the only

nation that produces self-flattering media. Using cultural nationalism to associate one’s people with positive or

superior qualities is rather common. For example, recall how many American sitcoms attempt to hammer home the

idea that Americans are hard-working or that Americans are friendlier than people of other nationalities.

23

that of the kokutai, or nation-body. Kokutai ideology defined the Japanese as “a community

bound together through a natural loyalty to the divine Tennō

11

as a father figure” (Godart 48).

Because the emperor was seen as a divine figure, prior to the end of WWII, many Japanese

people believed that Japan had a divine right to rule over other nations. However after the

unconditional surrender in 1945, subsequent occupation, and constitutional revision, the emperor

was no longer considered to be a living deity, effectively ending the age of using kokutai as a

basis for Japanese identity. During the same period, the Japanese government was also tasked

with remaking Japan’s image for the sake of its economy and future diplomacy. Despite

skepticism from neighboring countries, the government chose peace and harmony to represent

the new Japan, beginning their long journey towards reclaiming their role on the world stage.

Perhaps contradictory to Japan’s new direction, in the 1960s, a wave of scholarly

nationalism rose in Japan. Nihonjinron, or theories on the Japanese, were a type of scholarship

published by Japanese academics and scholars from various fields who sought to explain or

analyze the Japanese race and Japanese culture. Although similar works and schools of thought

existed during the pre-war period, nihonjinron itself did not gain much popularity until after the

war. Nihonjinron began as criticism and self-reflection on the hubris and ideals of the Japanese

empire that led to World War II. However when the American Occupation officially ended in

1952, perhaps out of pent up anxiety and resentment, there was a major shift to writing

nihonjinron that sought to analyze Japan’s past and identify what made its culture unique. From

there, nihonjinron became a hotbed of cultural nationalism.

The basic tenets of nihonjinron have been outlined as follows:

The only valid basis from which to study Japanese society is using native informants'

judgements (emic), as opposed to external or foreign analysis (etic).

11

Title of the Japanese emperor

24

The Japanese can be treated as a culturally and socially homogeneous racial entity, whose

essence is virtually unchanged through time.

The Japanese differ radically from all other known peoples in terms of society, culture,

and language.

Japanese “blood” is essential in order to understand Japanese society, culture, and

language.

Foreigners are incapable of completely understanding Japanese culture and language.

(Haugh 28)

While nihonjinron’s popularity peaked during the 1970s, it did not spark large waves of domestic

and foreign criticism until the late 80s and early 90s. Although the Japanese government never

officially endorsed nihonjinron, there were individual government officials who often alluded to

or promoted the genre. Due to the variety of stances within nihonjinron, some ideals were too

polarizing and controversial for the government to collectively incorporate into formal policy.

However, through Clean Japan, which dilutes the central concepts of nihonjinron and makes

them inconspicuous, the government has found ways to subtly support the genre.

Clean Japan operates within what Bukh calls a “particular understanding of reality” that

“targets the self-identity of the population in question and seeks to manipulate it” (465). Rather

than targeting academics, Clean Japan’s goal is to reach the masses. While the execution differs,

the core ideas of nihonjinron and Clean Japan remain the same. Bukh recalls Peter Dale’s

explanation that one of nihonjinron’s central arguments is that “Japan had consistently been a

harmonious, communal, and peaceful society, unlike the conflict-prone, individualistic, and

jingoistic West” (477). Harking back to Japan’s image promoted during the Olympics, we

continue to see “harmonious” and “peaceful” being attributed to the Japanese throughout the

Cool Japan Initiative’s advertising efforts and displays of Clean Japan.

25

Clean Japan exists on a spectrum with some manifestations being more inconspicuous or

more overt, despite all iterations pointing to the same idea. While nihonjinron itself may seem

too heavy-handed to the average citizen, Clean Japan is innocuous, accessible, and disguises

itself well in the media. Recalling Althusser, ISAs are meant to bridge the gap between the state

and private domains. Clean Japan is a very effective ISA due to how well it permeates into

different forms of media, especially television and anime.

Clean Japan and Media

Alexandra Hambleton asserts that “the media plays a great role in the formation of

Japanese perceptions of non-Japanese even within Japan,” but I would argue further that the

media also plays an important role in how the Japanese perceive themselves (32-33). When

Japanese citizens are constantly shown examples of Clean Japan in the media, it can begin to

warp their perception of Japanese society. One purpose of nurturing nationalism as an imaginary

universe is to allow the average citizen to impose an idealized version of the nation onto themself

and vice versa. If the media constantly espouses the idea that one’s nation is great, then citizens

of that nation will consider themselves great. On the other hand, when looking outward, Clean

Japan tends to highlight the differences of non-Japanese which “contribute[s] to the creation of

an ‘essentialized identity’” (Hambleton 43). This “essentialized identity” is the same identity

created by the Japanese government and maintained by cultural nationalists. When citizens who

have little contact with or access to foreign cultures are only shown negative or drastic

differences between them, it can skew their opinions on those cultures.

12

Conversely, when

12

This is not limited to fictional media, as Japanese news stations (usually controlled by the Liberal Democratic

Party) may only show crime reports or other unflattering coverage of certain groups if they are pushing a certain

agenda.

26

foreigners who know little about Japanese culture are shown Clean Japan, it may result in them

forming unrealistically high opinions of the Japanese.

Up until now, we have discussed Clean Japan with the assumption that audiences were

mostly unaware of the media bias, but what of those who are able to catch on and still choose to

believe in Clean Japan? For Japanese viewers, indulging in Clean Japan could simply be a matter

of pride. It is not far-fetched to argue that seeing such positive depictions of their nation in the

media can boost the egos of Japanese viewers. Like cultural nationalism, this in and of itself is

not uncommon, nor is it necessarily an issue. The problem lies within depictions of Japanthat are

completely one-sided or push false narratives in order to advance an agenda (political, economic,

or social). For others, Clean Japan might simply easier to believe than the truth, which is that

Japan is racially, linguistically, ideologically, and socio-culturally heterogeneous, just like every

other nation. Furthermore, because Japanese culture shares many similarities with its

neighboring Asian countries, there is no basis for the nihonjinron/Clean Japan argument that

Japan is more unique than other nations.

Clean Japan tends to only show viewers what it wants them to see, whether that be

through the generalization or selective filtering of Japanese culture. The erasure of Japanese

socio-cultural complexity within Clean Japan stems from nihonjinron, but presents the same

issue surrounding foreigners consuming mukokuseki media and using it to draw conclusions

about Japan in real life. Foreign audiences that are aware of Clean Japan, but choose to continue

consuming its oversimplified image of Japanese society, may do so in order to engage in

escapism.

Foreign escapism through anime can be attributed to Clean Japan or common themes

within the medium. The former requires viewers to believe that all the major facets of Clean

27

Japan are true in reality and grants them with the image of an idyllic nation where the streets are

safer than their own and the people are kinder and more welcoming. This image is identical to

the imaginary Japan that the Initiative uses to entice foreigners. Iwabuchi writes that Japanese

nationalists sometimes interpret the popularity of Japanese cultural exports in Asia as the idea of

“Asia-yearning-for-Japan,” in which Japanese technology and culture has become the aspiration

of Asian countries (66). In this case, however, rather than “Asia-yearning-for-Japan,” we have a

broader concept of all foreigners yearning for Japan. The second type of foreign escapism is due

more so to prevalent youth-related themes in anime, rather than Clean Japan alone. In other

words, instead of foreigners yearning for Japan, we have foreigners yearning for their youth

(through a Japanese lens).

Clean Japan and Anime

As previously stated, Clean Japan exists on a spectrum that consists of varied levels of

overtness. I will call less overt displays “soft” Clean Japan and more overt displays “hard” Clean

Japan. Soft Clean Japan is generally more subtle in its depiction of positive Japanese stereotypes,

whereas hard Clean Japan is much more transparent and biased in its representation of Japanese

characters. In this section, I will examine instances of Clean Japan in anime and attempt to

identify the reasoning and motivations behind their presence. Later, I will expand how foreigners

factor into Clean Japan and the effects of Clean Japan on the Cool Japan Initiative.

Asobi Asobase (2018) is a gag comedy anime based on Suzukawa Rin’s manga of the

same name. Asobi Asobase centers on three eighth grade classmates, Hanako, Olivia, and

Kasumi, as they search for fun games and activities to play afterschool in the “Pastimers Club”.

There are different degrees of Japaneseness present in Asobi Asobase where out of the three girls,

Kasumi is the “most Japanese” (or exhibits the most traits of Clean Japan) and Olivia is the least.

28

In the series, Kasumi is shown to be the most hygienic, polite, and sensible of the three (although

most of this is due to her role as the tsukkomi

13

of the group). As the main boke

14

, Hanako can be

categorized as a “deviant Japanese” character. She does retain aspects of Clean Japan (for

example, she excels in academic and physical performance), but is also shown to be more rash

and outspoken than Kasumi. Presumably due to her being white, Olivia is oftentimes more naive,

less studious, and less clean than both Hanako and Kasumi. Not unlike the cute, eye-catching

mascot characters found in genres such as mahō shōjo and kodomomuke (aimed at young

children), Olivia's name is simply “Olivia”—written in katakana

15

with no surname or indication

of her origins. Despite being a main character and some of the Japanese side characters having

full names, Olivia does not, which reinforces her foreignness and solidifies her place as the “least

Japanese” of the three.

There is a recurring gag in which various characters comment on the body odor of Olivia.

In one scene, Hanako has to sniff her clubmates’ underarms as a punishment game. When she

sniffs Kasumi, who is embarrassed and hesitant to raise her arms, Hanako reassures her that she

does not smell at all. However, when Olivia energetically lifts her arms for Hanako to smell,

Hanako recoils and screams “Apocrine sweat glands!” before falling to the ground and making

exaggerated faces and motions to express her disgust. In a later scene, when Olivia is horrified to

learn that all of her classmates are aware of her body odor, Hanako and Kasumi attempt to

comfort her by telling her that her smell “fall[s] under the action threshold in the Ministry of the

Environment’s odor index” and that they have already grown used to her odor (“Phantom

Thieves: Pass Club” 10:17). Other examples of this gag include a bacteria-detecting game on

13

The straight man in Japanese stand-up comedy routines (manzai); derived from the verb tsukkomu, meaning ‘to

thrust into’ or ‘to butt in’, the tsukkomi normally points out the boke’s ridiculous behavior.

14

The funny man in Japanese stand-up comedy routines (manzai); derived from the verb bokeru, meaning ‘to grow

senile’ or ‘to be mentally slow’, the boke normally engages in ridiculous behavior.

15

Japanese writing system used to write foreign words and onomatopoeia

29

Olivia’s phone that flashes red and blares alarms when pointed at her underarms and a baby who

yells “Spicy!” after catching a whiff of Olivia’s shirt.

This gag is based on a common gene allele in East Asians that causes the apocrine sweat

glands to not produce an odor, meaning they often have little to no body odor due to sweat

(Martin, et. al 529). Because Olivia is white, it’s insinuated she has the odor-producing allele

which makes her body odor stronger than her Japanese classmates’. To make matters worse,

Olivia initially seems oblivious to her body odor, although it is later shown that she suspected

that she smelled, but did not want to tell anyone. Because this gag is based on a biological fact, I

would label it as soft Clean Japan. Aspects of Olivia’s foreignness are also used in other gags

and jokes, but never maliciously or to solely make the J

apanese characters look better.

There are even moments when the concept of Olivia being “foreign” is turned on its head

in the anime. For example, although Olivia has blonde hair and blue eyes, she was born and

raised in Japan and knows little about the English language or Western culture. However, one of

her classmates, Fujiwara, has a face that looks exactly like a female Noh mask, but is not from

Japan and speaks in a mix of English and accented Japanese. When the two interact, the irony of

having a white character who is more Japanese than the girl who looks like a 19th century

Japanese woodblock print is made extremely clear. There are certainly issues with Olivia’s

Figure 7: Hanako's reactions to smelling Kasumi (left) and Olivia (right).

30

character, but they are not as severe as they could be. Overall, Asobi Asobase displays Clean

Japan that caters more to its Japanese characters by making them look better in certain aspects,

but does not completely disparage its foreign characters either.

A step-up from the Clean Japan found in Asobi Asobase, we have Bungou Stray Dogs

(2016). Bungou Stray Dogs (lit. Literary Stray Dogs) is an anime based on the 2012 manga by

Asagiri Kafka. The story follows the ADA (Armed Detective Agency), a government-run

organization in Yokohama that employs individuals who possess supernatural powers. Each

“gifted” character in the series is inspired by and shares a name with a famous literary author or

poet. The characters’ powers are also named after the most famous works by these literary

figures. For example, the characters Dazai Osamu and Akutagawa Ryuunosuke possess powers

called “No Longer Human” and “Rashōmon,” respectively. In the first season, viewers are

introduced to the main characters and the initial antagonists of the series, the Port Mafia. As an

underground criminal organization, Port Mafia members often find themselves engaged in battles

with the ADA. However, by the end of the first season, it is clear that both groups care about

Yokohama and strive to keep it safe, albeit for very different reasons. The consensus between the

organizations to protect Yokohama is important, because

it shapes their interactions in the next two seasons.

The second season focuses on the ADA battling

the Guild, an American secret society attempting to gain

complete control of Yokohama. The Guild consists of

numerous characters based on American authors like F.

Scott Fitzgerald (The Great Gatsby), Louisa May Alcott

(Little Women), and Mark Twain (The Adventures of

Figure 8: Members of The Guild from Bungou

Stray Dogs

31

Tom Sawyer). As the Guild wreaks havoc in Japan to fulfill their greedy, power-hungry goals,

the agency calls a ceasefire with the Port Mafia and teams up with them to defeat their Western

opponents. Throughout the season, we are shown how the Guild’s arrogance leads to them losing

battle after battle with the ADA and Port Mafia, who are eventually able to outsmart and whittle

down their forces.

Soon after the Guild is defeated, the ADA is faced with yet another threat—Fyodor

Dosteovsky (Crime and Punishment) and his organization of European authors who are

searching for a supernatural book that can alter reality. Although Dostoevsky hatches a plan to

have the ADA and Port Mafia destroy each other, ultimately they are able to band together and

stop the Russian’s plans. In seasons 2 and 3, there is a clear pattern of villains from the West

invading Japan. In order to stop them, the Japanese characters must put their differences aside to

save the city, country, and later, the world. While the Western antagonists are not always written

having the same character flaws, they are often shown to be more callous, prideful, and power-

hungry than the Japanese characters. Furthermore, if Dostoevsky is revealed to be the true villain

of the series, then a large portion of Bungou Stray Dogs’ plot will have involved the Japanese

protagonists being pitted against Western antagonists.

One specific example of Clean Japan in the series is the relationship between Edogawa

Ranpo (Black Lizard) and Edgar

Allen Poe (“The Raven”). The real

Edogawa Ranpo held a deep

admiration for Poe’s work and

based his pseudonym on Poe’s

Figure 9: Poe (left) speaking to Edogawa (right) in Bungou Stray Dogs

season 2, episode 10

32

name.

16

However, in Bungou Stray Dogs, the roles are reversed. Although his feelings are

initially framed as resentment, Edgar Allen Poe is the one who admires Edogawa and spends six

years planning a mystery to stump him, which is ultimately solved within a few minutes. While

Edogawa acknowledges that he enjoys solving Poe’s puzzles, there is a clear imbalance between

how the characters view each other. The series makes it clear that Edogawa is the superior

detective while Poe sees him as something of a rival and aspiration.

17

Although Bungou Stray Dogs has a tendency to depict Western authors as antagonists or

inferior to their Japanese counterparts, I do not believe that these displays are offensive enough

to categorize the series as hard Clean Japan. While the Japanese characters do enjoy more nuance

and flexibility regarding who is “bad” versus “good,” the Clean Japan present in the story does

not outright condemn or portray every foreign character as evil. On the other hand, because

Bungou Stray Dogs’ Clean Japan is more overt and clear-cut than what is found in Asobi

Asobase, I would place the series somewhere in-between soft and hard Clean Japan.

Clean Japan and Anime: Hetalia

Finally, we will be examining Clean Japan in Hetalia: Axis Powers (2006), a webcomic

that has spawned several manga, anime, film, and musical adaptations. The series is set in a

world where nations are personified and interact with each other according to historical events.

The story begins during World War II, but eventually covers a wide range of historical and

sociopolitical topics from many regions in Asia, North America, and Europe. While Hetalia’s

initial audience consisted primarily of Japanese adults, licensing changes and increased access to

16

The name is derived from the katakana reading of Edgar Allan Poe ( ).

17

It is worth mentioning that Bungou Stray Dogs does feature other inverted relationships between its characters and

their real-life counterparts, such as Dazai being Akutagawa’s mentor and role model in the story, despite the real

Dazai Osamu being heavily influenced by Akutagawa Ryuunosuke’s work.

33

the series resulted in Hetalia gaining popularity among younger audiences. The first manga

series, Hetalia: Axis Powers, was published in the seinen manga magazine Comic Birz from

2006 to 2013. The 2009 anime adaptation of Axis Powers was initially planned to air on Kids

Station, a Japanese television network that, not unlike Cartoon Network and Adult Swim in the

U.S., broadcasts child-friendly anime during the daytime and adult-oriented anime at night (Loo

1). Due to controversy surrounding the series, Kids Station cancelled their plans to broadcast the

first season of Hetalia: Axis Powers, which was released as an Online Net Animation (ONA)

instead. When the anime was licensed by Funimation in 2010, it was given a TV-MA rating for

“some instances of profanity, crude humor and adult situations” (@FUNimation). At the time,

the entire series was available to watch on Funimation’s official YouTube channel. Although the

mature rating meant the videos were age-restricted, viewers could bypass this by uploading the

episodes to other websites or changing their profile age on YouTube.

In 2014, the series lowered its target demographic with the release of the second manga

series, Hetalia: World Stars, in Shōnen Jump+, an online magazine aimed at young boys.

Despite the series officially being marketed towards male audiences, the majority of Hetalia’s

fanbase has consisted of girls and young women since the late 2000s.

18

Since a large number of

teenagers and children now consume the series alongside adult viewers, it has become difficult to

ascertain which audience members are able to discern the nationalistic subtext within Hetalia.

Although some viewers believe that Hetalia is not nationalistic, the series’ self-flattering

depiction of Japan, distorted portrayal of foreign nations, and references to nationalistic trends

and terms firmly place Hetalia in the hard Clean Japan category.

18

Hetalia’s popularity with female consumers is most likely due to the series’ majority male cast. As Miyake Toshio

notes in his article on Occidentalism and sexualized parody in Hetalia: Axis Powers, if Himaruya wanted his works

to appeal to male audiences, he could have drawn majority of the nations in moe-kyara style as cute or sexy female

characters (5.8). Instead, the overwhelming majority of the cast are male and fit into various character tropes that

appeal to female audiences, especially fujoshi or female otaku who enjoy “parodies of male-male intimacy” (Miyake

0.1).

34

A Clean Japan

Sands, like many other fans of Hetalia, argues that the series is not nationalistic or racist

because it does not “[glorify] Japanese culture or ethos” and that Japan is often “humiliated” by

other characters when he is pulled into their shenanigans and made to look silly (129, 132).

However, glorifying Japan is not the approach Hetalia takes to demonstrate cultural superiority.

Instead, Himaruya writes scenarios in which Japan is often the sole voice of reason and maturity.

When the other nation-characters engage in ridiculous behavior (which they do often), their

strangeness juxtaposed with Japan’s “normal” reactions makes Japan look better by default. The

result is Japan literally being portrayed as the world’s tsukkomi.

Japan’s depiction in Hetalia is more or less the embodiment of Clean Japan. Two of

Japan’s most revealing character descriptions are from the third volume of Axis Powers and the

first of World Stars. Japan is described as a “quiet, serious, Oriental, warrior nation” and “a

serious samurai nation who values harmony” (“Japan” 4, 8 [Hetarchives]). His only glaring

character flaws are that he’s very shy, at times reclusive, and acts like an “old man” (“Japan”

[Kitawiki]). Hetalia’s characters are said to represent both the positive and negative stereotypes

associated with their respective countries, but in Japan’s case, even his “negative” stereotypes

are inoffensive, as they pose no threat of meiwaku.

The concept of meiwaku, meaning nuisance or inconvenience, is extremely important in

Japanese society. In terms of interpersonal interactions, meiwaku is used to describe actions and

behavior that impose on or inconvenience others. Similar to the “Golden Rule” in the West, the

concept of meiwaku and how to avoid it are ground into the consciousness of those living in

Japan from a young age. While Sands and others have pointed out that Japan is also mocked and

35

depicted with unflattering traits in Hetalia, the difference lies in how little meiwaku Japan’s

character flaws pose to others. Japan being old-fashioned or shy is not going to be interpreted as

negatively as China’s character flaw of violating copyright laws or America’s habit of “sticking

his nose everywhere” (“United States of America” 3). Because all the other characters do have

flaws that impose meiwaku while Japan does not (or has mild ones in comparison), Japan

maintains his image of looking better than the other nations.

Tsukkomi as Japaneseness

In my analysis of Asobi Asobase, I mentioned that Kasumi’s role as a tsukkomi

contributed to her Japaneseness and that Hanako’s role as a boke classified her as a “deviant

Japanese” character. Because similar patterns can be found in Hetalia and other anime with

Clean Japan, I would like to explain how Clean Japan affects the comedic roles of tsukkomi and

boke. Boke-tsukkomi roles in anime usually surface when the boke makes an outlandish or

foolish comment on their surroundings, the situation, or something they’ve done and the

tsukkomi points out the errors in their logic. These roles are very common in anime and manga,

especially in genres like slice-of-life and, naturally, comedy. However, because the attributes

Clean Japan associates with the Japanese are also found in tsukkomi characters, tsukkomi ends

up being aligned with Japaneseness. Essentially, the more a character’s personality or behavior

fits the tsukkomi role, the more Japanese they seem.

The role of tsukkomi is usually associated with level-headedness, common sense,

intelligence, and overall standard behavior. Although tsukkomi may have flashes of hot-

headedness or be quick to yell at and hit the boke (a direct throwback to traditional manzai

routines), this is primarily for comedic effect and does not undermine the delivery of the

36

tsukkomi’s rationale. On the other hand, boke are commonly associated with airheadedness,

stupidity, and ignorance. The boke role translates as deviant due to how often they ignore or are

unaware of behavioral standards. Both nihonjinron and Clean Japan operate under the

assumption that the Japanese are collectivist, which means that for the good of the group, they

should avoid standing out and imposing meiwaku on others. In order to do this, the characters

need to avoid engaging in deviant behavior, which translates to their actions aligning with

tsukkomi rather than boke.

Sometimes boke-tsukkomi manifest as more flexible roles, where even after a character is

given the official role of tsukkomi or boke within their circle, during gags or comedic situations,

there is still flexibility for the roles to reverse in such a way that the tsukkomi does something

silly and the boke becomes the straight man. When the boke interjects with logic, it heightens the

comedic effect by making the recipient look less intelligent than the boke. This method of

making people look foolish occurs fairly frequently when foreigners are involved.

Boke characters are commonly depicted as friendlier, more outspoken, or more energetic

than tsukkomi characters. Coincidentally, these are also traits that are often associated with

Westerners (with some exceptions)

19

, resulting in a high number of Western boke characters in

anime (if they are not already in another archetype). Furthermore, because these foreign

characters are more likely to commit cultural faux pas, it is easy to create a dynamic where you

have both the Japanese tsukkomi and boke correcting the outsider’s unintentional boke. Hetalia

contains examples of both, with most of the Eurocentric cast being boke and Japan (and

occasionally China) calling out their stupidity.

19

There is a trend in Japanese media of portraying Russians as very serious, intelligent, or stoic, the French as very

sophisticated or romantic, etc.

37

Despite, or perhaps due to, most of Hetalia’s characters being Western, there are a few

notable non-Asian tsukkomi. Of the Allied Forces and Axis Powers, England, occasionally

China, Germany, and Japan act as tsukkomi, while the remaining countries are usually boke.

England is portrayed as a more stereotypical anime tsukkomi (i.e. he’s a tsundere

20

and

somewhat hot-headed), usually to America or France’s boke. Like most tsukkomi, he often

interjects by yelling or hitting the boke. Germany, in a similar vein, is more of an intimidating

tsukkomi and will often correct the boke’s (normally Italy) behavior by yelling or threatening

violence. Japan, however, has a quieter, calmer tsukkomi style. Depending on which boke he is

confronted with, Japan will either begin by calmly addressing the boke’s error or reluctantly

stutter his way through a retort. If all else fails, Japan might yell or exclaim something briefly,

but by-and-large, he is portrayed as a very calm tsukkomi, which in turn continues to align his

character with Clean Japan.

Taiwan: Asia-yearning-for-Japan

Hetalia contains a series of gags and stories with literal depictions of Asian countries

yearning for Japan and aspects of Japanese culture. Taiwan is the Asian nation-character most

outspoken about her infatuation with Japan. Historically, although Taiwan was occupied by

Imperial Japan, the Taiwanese were not subjected to the same level of brutality and aggression

that colonies such as Korea and areas of Northeastern China faced. Due in part to this, anti-

Japanese sentiment was much lower in post-war Taiwan and in the 1990s, a change in

Taiwainese copyright laws brought Japanese anime, manga, and TV dramas to the country,

resulting in a “Japanophile phenomenon” (Chang 179-180). In Hetalia, this phenomenon is

20

A Japanese term used to describe characters who are initially portrayed as standoffish or temperamental before

showing a caring, friendlier side of their personality; derived from the onomatopoeic words tsuntsun, meaning ‘aloof’

or ‘standoffish’, and deredere, meaning ‘lovestruck’ or ‘fawning’.

38

reflected in Taiwan’s love of the Japanese kawaii (cute) aesthetic and her enthusiasm when

speaking with Japan. Many Japanophiles in Taiwan are teenage girls and, coincidentally, the

character of Taiwan reflects that as well, with her physical

appearance being that of a teenager. Within the series, Taiwan

and Hong Kong are often seen joking about China’s age and

outdatedness, but despite Japan also canonically being

thousands of years older than them, he is never made fun of,

presumably due to his pop culture being seen as more trendy

and original than China’s.

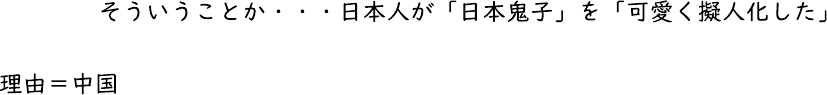

In Hetalia’s 2013 Halloween comic, Taiwan is shown wearing a kimono, fake horns, and

a demon mask. When the other characters assume that she is dressed as a ghost, Taiwan happily

corrects them that she is dressed as Hinomoto Oniko. During the late 2000s, a trend arose in