Application of the

Balanced Scorecard in

Higher Education

Opportunities and Challenges

An evaluation of balance scorecard implementation at the College of St. Scholastica.

by Cindy Brown

Introduction

In the 1990s a new way of evaluating performance

improvement in the business industry was introduced.

The balanced scorecard (BSC) emerged as a conceptual

framework for organizations to use in translating their

strategic objectives into a set of performance indicators.

Rather than focusing on operational performance and the

use of quantitative financial measures, the BSC approach

links the organization’s strategy to measurable goals and

objectives in four perspectives: financial, customer, internal

process, and learning and growth (Niven 2003).

The purpose of this article is to evaluate the use of the

BSC in the nonprofit sector, specifically at an institution of

higher education. Case studies in higher education and

personal perspectives are presented, and the opportunities

for and challenges of implementing the BSC framework in

higher education are discussed.

Balanced Scorecard Principles

Achievement of equilibrium is at the core of the BSC

system. Balance must be attained among factors in three

areas of performance measurement: financial and nonfinancial

indicators, internal and external constituents, and lag and

40 July-September 2012 |Copyright © Society for College and University Planning (SCUP). All rights reserved.

Cindy Brown, DNP, MPH, RD, RN is an

assistant professor in the School of Nursing

at the College of St. Scholastica in Duluth,

Minnesota. Her professional expertise is in

public health, nutrition, and chemical

dependency. She also provides nursing

services at a housing facility for residents

with chronic alcoholism. She has an interest

in performance improvement evaluation in

higher education; this article is a culmination

of her review and application conducted as

part of her graduate course work for her

doctorate of nursing practice degree.

lead indicators. Equilibrium must also be attained between

financial and nonfinancial measures; nonfinancial measures

drive the future performance of an organization and are

therefore integral to its success. Further, the use of

nonfinancial measures allows problems to be identified and

resolved early, while they are still manageable (Gumbus

2005). The sometimes contradictory needs of internal

constituents (employees and internal processes) and

external stakeholders (funders, legislators, and customers)

should be equally represented in the scorecard system

(Niven 2003). A key function of the BSC is its use as a

performance measurement system. The scorecard enables

organizations to measure performance through a variety of

lead and lag indicators relating to finances, customers,

internal processes, and growth and development (Niven 2003).

According to Niven (2003), lag indicators are past performance

indicators such as revenue or customer satisfaction,

whereas lead indicators are “the performance drivers that

lead to the achievement of the lag indicators” (p. 23).

The BSC framework provides tools to assist business

organizations in mapping their performance improvement

strategies and establishing connections throughout the various

levels of the organization. Additionally, the framework

identifies cause-and-effect relationships. The strategy map

component of the BSC provides a graphical description of

the organization’s strategy, including the interrelationships

of its elements. This map is considered the blueprint for

the organizational plan (Lichtenberg 2008). Further, the

BSC’s cascading process gives the organization a tool for

taking the scorecard down to departmental, unit, divisional,

or individual measures of performance, resulting in a

consistent focus at all levels of the organization. Ideally,

these measures of performance at the various levels directly

relate to the organizational strategy; if not, the organization

is just benchmarking its metrics. The cascading of the

scorecard also presents employees with a clear image of

how their individual actions make a difference in relation

to the organization’s strategic objectives. The cascaded

scorecard creates alignment among the performance

measurement outcomes throughout the various levels of

the organization (Lichtenberg 2009).

The BSC has evolved into a powerful communications

tool and strategic management system for profit-based

organizations. Harvard Business Review has recognized the

framework as one of the top 75 most influential ideas in

the 21st century (Niven 2003). Its successful use in the

for-profit arena has been clearly demonstrated, but does it

have applicability in the nonprofit sector, specifically in

institutions of higher education (IHEs)?

Use of Performance Indicators in Higher

Education

Like other nonprofit organizations, IHEs are increasingly

under pressure to provide external stakeholders such as

communities, alumni, and prospective students with

performance indicators that reflect the overall value

and excellence of the institution. Historically, however,

performance indicators in higher education have

emphasized academic measures (Ruben 1999). Driven by

external accountability and comparability issues, IHEs often

focus on quantitative academic variables such as faculty

demographics, enrollment, grade point average, retention

rates, faculty-student ratios, standardized test scores,

graduation rates, faculty teaching loads, and faculty scholarly

activity (Ruben 1999). IHEs often assume that measuring

external accountability through one-dimensional parameters

such as college rankings or accrediting agency mandates

will influence internally driven parameters related to

institutional effectiveness; yet, unless these indicators are

linked in a meaningful way to the drivers of institutional

effectiveness, desired improvements in service, productivity,

and impact are unlikely to occur (Stewart and Carpenter-Hubin

2000–2001). Additionally, some of these academic variables

do not reflect the value that the IHE adds through the

teaching and learning process but instead reflect students’

existing capabilities (Ruben 1999).

Another challenge in using traditional measures of

excellence in higher education is their failure to capture a

comprehensive image of the institution’s current status

(Ruben 1999; Stewart and Carpenter-Hubin 2000–2001).

Further, the tendency for IHE performance indicators to

focus on external accountability fails to account for the

importance of internal assessment. Inclusion of internal

assessment indicators broadens perspectives and, if done

correctly, provides a connection between the institution’s

values and goals (Stewart and Carpenter-Hubin 2000–2001).

Indicators used in traditional higher education performance

Application of the Balanced Scorecard in Higher

Education: Opportunities and Challenges

Planning for Higher Education | Search and read online at: www.scup.org/phe.html 41

The BSC’s cascading process results

in a consistent focus at all levels of

the organization.

measurement frameworks cannot be adequately translated

into meaningful applications for the purpose of monitoring,

planning strategically, or conducting comparative evaluations

against standards of excellence among IHEs (Johnson and

Seymour 1996, as cited in Ruben 1999. These traditional

performance indicators also lack the predictive power

necessary to adequately alert IHEs of needed changes

in a timely manner. In addition, traditional models for

measuring higher education performance are constrained by

departmental boundaries and are limited in their ability to link

individual performance objectives and performance evaluation

processes with institutional performance (Hafner 1998).

Not as much emphasis is placed on other less tangible

indicators in higher education such as relevance, need,

accessibility, value added, appreciation of diversity, student

satisfaction levels, and motivation for lifelong learning; yet,

a common mission of IHEs is to foster lifelong learning.

Many of these indicators, especially those related to

student and faculty expectations and satisfaction levels,

deserve greater attention; recruiting, retaining, and nurturing

the best and brightest individuals is the primary goal of

IHEs (Ruben 1999). Despite this, the five most common

performance-based measures used in higher education

are retention and graduation rates, faculty teaching load,

licensure test scores, two- to four-year transfers, and use

of technology/distance learning (Burke 1997).

Absent from these common performance-based

indicators are the measurement categories and specific

metrics suggested by a BSC approach. IHEs need measurable

indicators that reflect value and excellence achieved

through investments in technology, innovation, students,

faculty, and staff (Nefstead and Gillard 2006). Current

ranking systems in higher education consider the multiple

facets of higher education but do not offer guidance on the

selection and organization of performance measures in

terms of performance drivers or diagnostic indicators.

Moreover, these ranking systems often do not relate

performance indicators to the institution’s mission or

provide guidance toward continuous quality improvement

(Beard 2009).

The Balanced Scorecard and Higher

Education

While implementation of the BSC cannot guarantee a

formula for accurate decision making, it does provide

higher education with “an integrated perspective on

goals, targets, and measures of progress” (Stewart and

Carpenter-Hubin 2000–2001, p. 40). Some IHEs have taken

the step of measuring performance indicators through the

implementation of a BSC approach. These IHEs have

identified the important characteristics of the scorecard:

inclusion of a strategic plan; establishment of lag and

lead performance indicators; improvement of efficiency,

effectiveness, and overall quality; and inclusion of faculty

and staff in the process (Rice and Taylor 2003). Successful

implementation of the BSC framework in higher education

relies on the progression through various steps as part

of the process. The first step is clear delineation of the

mission and vision, including translating this vision into

specific strategies with a set of performance measures.

The next step is establishing communication and linkage

among schools, departments, student support services,

institutional advancement, and other offices such as

physical plant and maintenance services. This step is

important in establishing direct connections between the

individual unit goals and objectives and the macro-level

institutional goals. To increase the potential for success, it

is imperative that administrators develop specific strategies

to achieve goals and allocate sufficient resources for these

strategies. Credible measures of progress toward these

goals must also be instituted. The final step involves creating

a feedback mechanism whereby the IHE can evaluate its

overall performance using updated indicators and revise

its strategies when needed (Stewart and Carpenter-Hubin

2000–2001).

Application of the Balanced Scorecard

Framework in IHEs

There is a dearth of published literature regarding BSC

applications in IHEs. Beard (2009) believes that this may be

attributed to a lack of knowledge and awareness of the

opportunities for BSC application rather than to incongruence

between the BSC approach and higher education strategic

planning. Scholey and Armitage (2006) suggest that as

IHEs are expected to develop more innovative programs

and also demonstrate greater fiscal and customer

Cindy Brown

42 July-September 2012 | Search and read online at: www.scup.org/phe.html

Traditional models are limited

in their ability to link individual

performance objectives with

institutional performance.

accountability, more will adopt the BSC framework. Others

contend that the lack of a detailed, systematic process for

executing the BSC model has hindered its widespread use

in IHEs; as a result, they have developed models for its

application in higher education (Asan and Tanyas 2007;

Karpagam and Suganthi 2010). Asan and Tanyas (2007)

presented a methodology that integrates the BSC (a

performance-based approach) with Hoshin Kanri (a

process-based approach). Karpagam and Suganthi (2010)

created a generic BSC framework to assist IHEs in

assessing overall institutional performance through the

use of identified higher education measurement criteria

that lead to the establishment of benchmarks and quality

improvement goals.

Despite the reluctance of IHEs to adopt standard

innovations (Pineno 2008), there are some documented case

studies in which the BSC approach has been successfully

implemented in IHEs both nationally and internationally.

From an international perspective, authors in both Australia

and Canada have published case-study data on the use of

the BSC approach (Cribb and Hogan 2003; Mikhail 2004).

Additionally, colleges and university systems in the United

States that have documented their use of the BSC include

the University of California System, Fairfield University,

University of Wisconsin-Stout, and the University of

Minnesota College of Foods, Agricultural and Natural

Resource Sciences (Nefstead and Gillard 2006).

Bond University in Australia initiated a BSC approach

for performance improvement. The library unit at Bond

University used the university’s vision, mission, strategies,

and performance goals to develop and implement its own

BSC. As part of the process, the library’s senior and middle

managers provided input on strategic objectives and

proposed metrics. This process also included the linkage

of measures through cause-and-effect relationships. An

identified challenge involved narrowing the list of possible

measures to the select few that would best capture the

core of the desired strategy (Cribb and Hogan 2003). The

library’s objective for each of its perspectives closely aligned

with the university’s objectives. For example, under the

customer perspective, the university defined customer

satisfaction as an objective. The library then identified its

own objectives focused on the assurance of customer

satisfaction through a variety of strategies, including an

emphasis on available resources and services as well

as effective collaboration and communication with

academic staff.

In developing financial measures, Bond University

initially decided to use library resources in relation to

student numbers to measure the library’s role in achieving

cost-effectiveness. However, since the university had lower

student enrollment and smaller economies of scale in

comparison to other universities in Australia, this financial

measure did not adequately reflect the relationships among

library expenditures, usage, student educational achievement,

and customer satisfaction. Therefore, additional measures

were identified to more accurately support both the library’s

and university’s objectives. A key factor that contributed

to the successful implementation of the BSC at Bond

University was the involvement of staff in the process;

staff involvement created an alignment between both the

library’s and university’s strategic objectives (Cribb and

Hogan 2003).

Ontario Community College in Canada also shared its

application of the BSC. The college substituted a strategic

goals perspective for the financial perspective typically

used in the BSC framework. This perspective was intended

to identify “how we should appear to our shareholders” in

order to succeed (Mikhail 2004, p. 9). The college identified

the following strategic goals: (1) achieve academic/service

excellence, (2) manage enrollment growth, (3) develop

strategic partnerships, (4) achieve organizational success,

and (5) manage cost-effectiveness and achieve a balanced

budget (Mikhail 2004).

In the mid-1990s, the University of California System

initiated a “Partnership for Performance,” a collaborative

effort involving the development and implementation of a

BSC framework throughout the nine distinctly different

campuses. The system executed specific approaches that

contributed to the overall success of this initiative. Senior

administrative managers from each campus participated in

the development of the overall vision and goals for business

administration and operations. This administrative group

also served as a steering committee over the life of the

initiative by providing direction, prioritizing, solving problems,

and encouraging and motivating their staff to participate.

The five business areas on each campus—human resources,

facilities management, environmental health and safety,

information technology, and financial operations—piloted

the development of common BSC measures. Creating a

performance measurement culture was challenging, but

part of the system’s success in achieving this culture

resulted from the creation of “performance champions

groups” that met quarterly to exchange dialogue and

Application of the Balanced Scorecard in Higher

Education: Opportunities and Challenges

Planning for Higher Education | Search and read online at: www.scup.org/phe.html 43

information related to organizational performance measurement

and management. As a result of the initiative, two of the

campuses adopted the BSC as a strategic planning tool for

business administration at the university level (Hafner 1998).

The Fairfield University School of Business designed

a phased approach for the implementation of the BSC

framework at the academic unit level. The phases of the

strategy revitalization process included building a foundation,

developing the scorecard, compiling measures, analyzing

results, recommending changes, revising measures, and

implementing initiatives (McDevitt, Giapponi, and Solomon

2008). The university also defined its own perspectives that

it felt were more appropriate to academics, including growth

and development, scholarship and research, teaching and

learning, service and outreach, and financial resources.

In some instances, the university needed to adopt a

benchmarking program; in others, it changed its metrics

because information was not available or easily accessible.

During the analysis phase, metrics were reevaluated and

faculty members were assessed on their ability to meet goals.

Faculty metrics included numbers and types of “intellectual

contributions,” measured through refereed publications and

attendance at or sponsorship of pedagogical seminars

(McDevitt, Giapponi, and Solomon 2008, p. 45).

Fairfield University’s School of Business had difficulty

in maintaining momentum throughout the implementation

of the program. The institution found it challenging to develop

effective measures to meet long-term qualitative goals and

to create effective communication strategies across work

groups, which led to delays in establishing consensus

within and among the various groups. Key outcomes of this

revitalization program included creating a communications

network between faculty and staff, increasing faculty

awareness of the institution’s goals and objectives, and

identifying and documenting needs for the purpose of

determining budget and funding (McDevitt, Giapponi, and

Solomon 2008).

The University of Wisconsin-Stout, another BSC

implementer, was one of the first three organizations to

receive the Baldrige education award (Karathanos and

Karathanos 2005). The Malcolm Baldrige Education Criteria

for Performance Excellence was designed to recognize

integrated performance measurement in IHEs that includes

(1) the delivery of ongoing value to stakeholders, (2) the

improvement of the institution’s overall effectiveness and

capability, and (3) the promotion of organizational and

individual learning. The Baldrige National Quality Program

criteria focus on results and creation of value. Its requirement

of an institutional report with comprehensive measures

comprised of both leading and lagging performance indicators

is consistent with the basic premise of the BSC framework

(Beard 2009; Karathanos and Karathanos 2005).

Balanced Scorecard Application at a

Select IHE

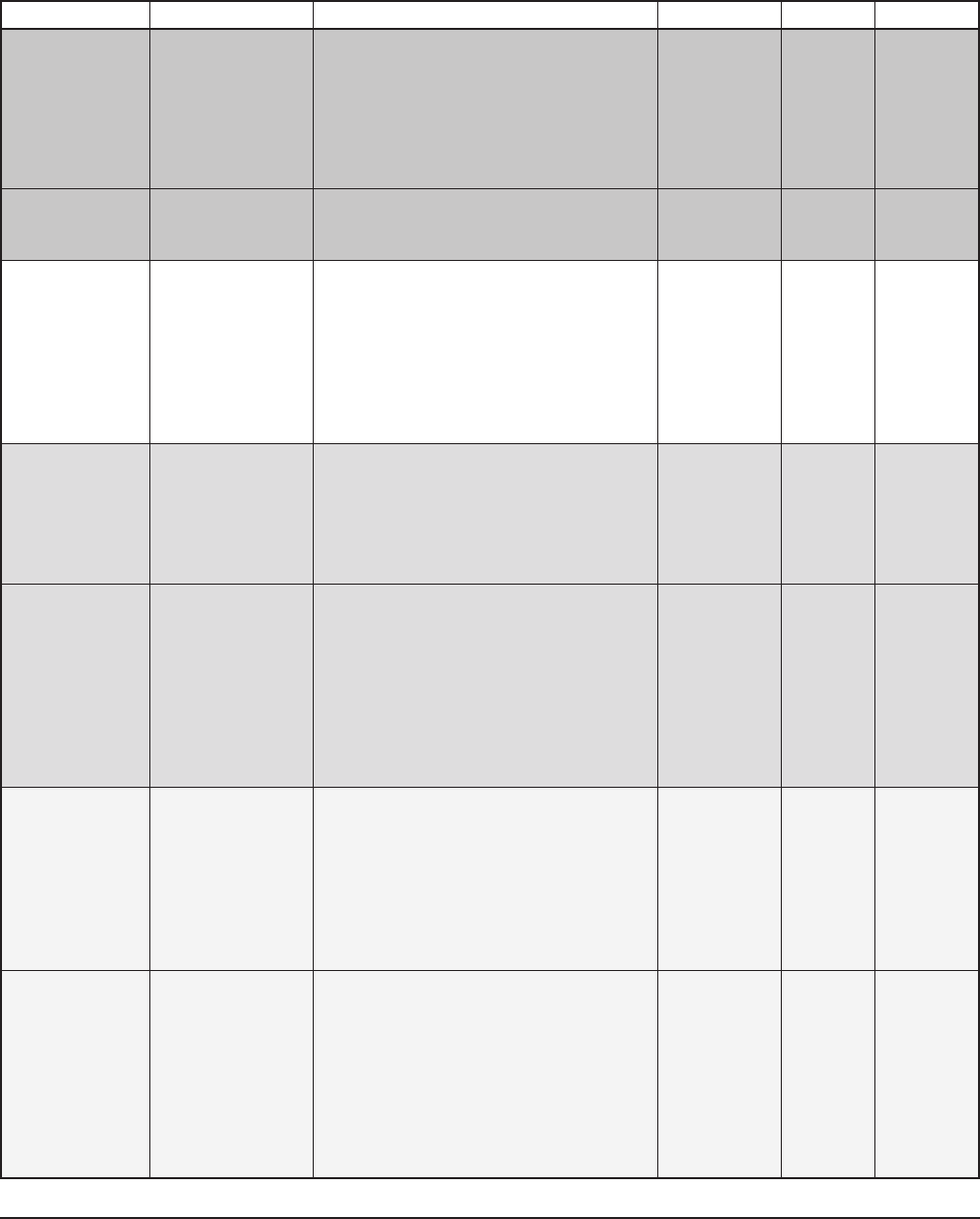

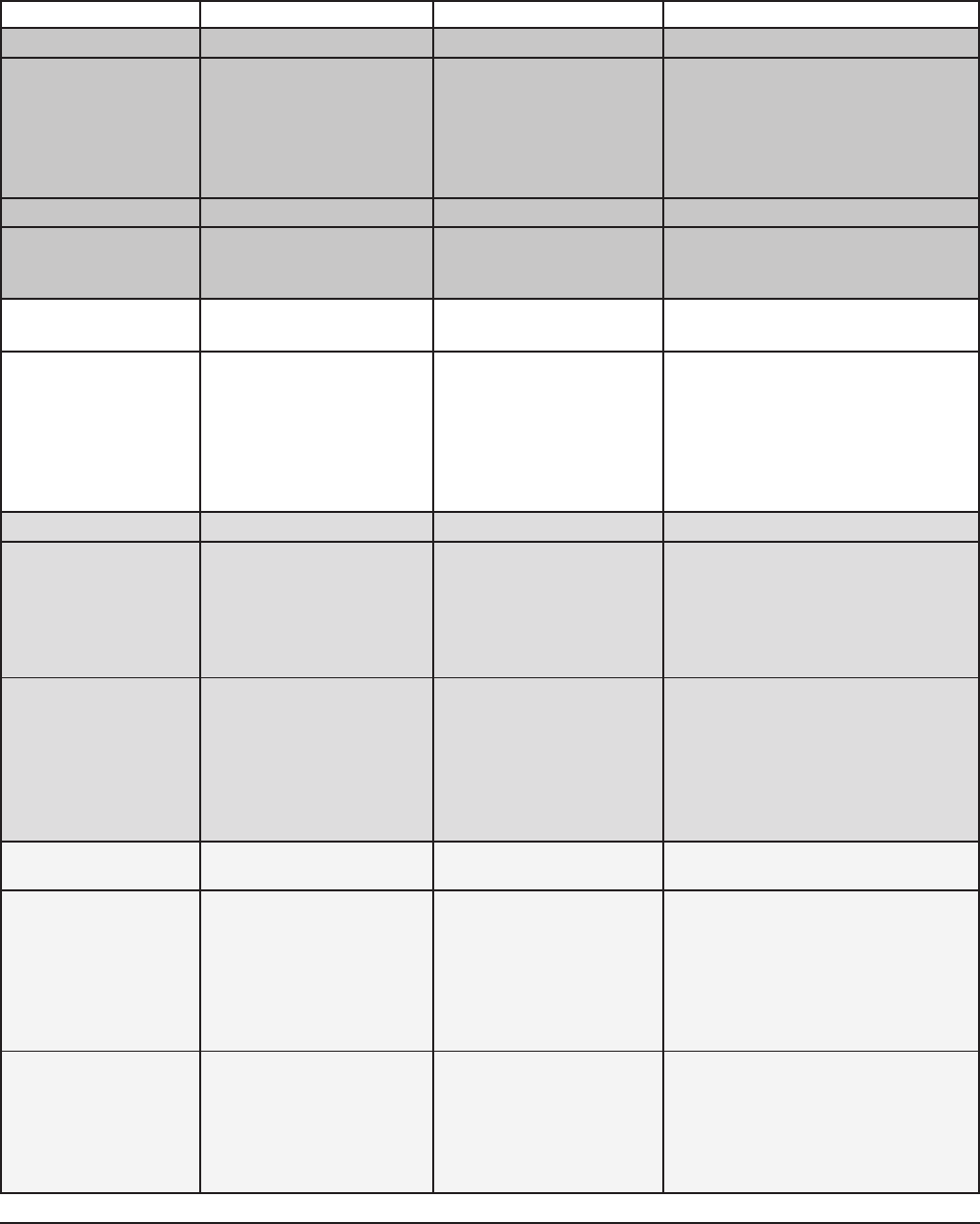

A BSC, including a strategy map and departmental

improvement plan, was developed for a select IHE

(figures 1, 2, and 3, respectively). This IHE is a small liberal

arts college located in northern Minnesota, rich in its

Benedictine heritage and Catholic tradition. Applying

Stewart and Carpenter-Hubin’s (2000–2001) process, the

IHE first identified strategies/objectives and performance

measures that fit with the distinct mission and vision of the

college. The strategy map (figure 2) was an invaluable

resource in expressing the cause-and-effect relationships

among the various perspectives. The strategy map provided

useful visual connections that illustrated the college’s overall

calculated planning process, which helped generate faculty

and staff buy-in to the BSC approach. For example, faculty

could see how their work in strengthening and creating

new academic programs and program delivery systems

affected other performance indicators such as improving

student satisfaction and increasing enrollment growth in

extended studies programs. Similarly, staff could gain an

understanding of how their commitment to strengthening

student support services and enhancing service-learning

experiences affected the student experience and

community partnerships.

Once the overall strategies were identified in each

of the four perspectives—financial, internal processes,

students and community, and learning and growth—it was

relatively easy to develop School of Nursing (SoN) and

undergraduate nursing department-based objectives that fit

with the institution’s overall objectives/goals through the

process of cascading, as illustrated by the BSC performance

improvement plan (figure 3). As a nursing faculty member,

it was beneficial to see how the undergraduate nursing

department’s objectives were linked to the overall college

objectives. For example, strategies from the internal process

dimension at the college level included strengthening the

Benedictine Liberal Arts (BLA) program and enhancing

student service-learning experiences. Measures related to

achieving these strategies at the undergraduate nursing

Cindy Brown

44 July-September 2012 | Search and read online at: www.scup.org/phe.html

Application of the Balanced Scorecard in Higher

Education: Opportunities and Challenges

Planning for Higher Education | Search and read online at: www.scup.org/phe.html 45

STRATEGY

A. Manage

enrollment

growth

B. Secure

capital funds

C. Increase

student

satisfaction

D. Strengthen the

Benedictine

Liberal Arts

program

E. Enhance

service-learning

experiences

F. Support faculty

professional

practice and

research

G. Strengthen

information

technology

infrastructure

MEASURE

Increase student

enrollment in Adult

Day and Evening

Programs (ADEP),

extended sites,

and with the three

online initiatives.

Seek private donor

funding through

capital campaign.

Increase students’

overall satisfaction

with their college

experience.

Develop a

Benedictine Liberal

Arts program that

aligns itself with the

mission and values

of the college.

Increase

service-learning

opportunities

and student

participation.

Expand faculty

development

funding to support

faculty advance

practice and

research.

Provide a

competitive

technology

infrastructure

that supports the

needs of students,

faculty, and staff.

FREQUENCY

Monthly

Quarterly

Annual

Graduation

Satisfaction

Survey

Annual

Semi-annually

Semi-annually

Quarterly

FINDINGS

TRENDING

TARGET

1) Ten percent increase in student

enrollment at each ADEP extended

site: Brainerd, St. Cloud, St. Paul,

and Rochester.

2) Twenty percent increase in the three

online initiatives: RN to BS, HIIM

Master’s, and DPT programs.

Obtain 10 percent of estimated $15

million for Science building expansion

from private donations.

1) One hundred percent of students will

report being “satisfied” or “very

satisfied” with their overall experience

at the college.

2) One hundred percent of students

will report being “satisfied” or “very

satisfied” with their preparation for

future work.

1) Implementation of new Benedictine

Liberal Arts program beginning Fall

of 2011.

2) By Fall of 2011, 25 percent of the

Benedictine Liberal Arts program will

be available in an online format.

1) Each school—Education, Management,

Business & Technology, Health

Science, Sciences, Nursing, and Arts

& Letters—will add at least two new

service-learning experience options

each semester.

2) Prior to graduation, 100 percent of

students will participate in a service-

learning experience.

1) Five percent of entire faculty each

year will become eligible for associate

professor status through achievement

of a terminal degree and advance

research.

2) These faculty receive 50 percent

funding, up to $10,000/year, for

advanced education/research.

1) Each school within the college has

its own designated academic IT

development/support staff in proportion

to its number of programs and departments.

2) IT Help “desk” support is available

7 days per week.

3) One hundred percent of college

classrooms and labs are evaluated

for supportive technology needs.

Figure 1 Balanced Scorecard

Cindy Brown

46 July-September 2012 | Search and read online at: www.scup.org/phe.html

Figure 2 Balanced Scorecard Strategy Map

Finance

As financial

stakeholders, how

do we intend to meet

the mission and

vision and foster the

Benedictine values?

Students and

Community

What do the

community and

students expect,

want, and need

from the college?

Internal Processes

As members of the

staff, what do we

need to do

to meet the needs

of our students and

our community?

Learning and Growth

As an organization,

what type of culture,

skills, training, and

technology are we

going to develop

to support

our processes?

Achieve financial

stability with reserves

STUDENTS COMMUNITY

A

B

C

D

F

G

E

Managed enrollment

growth

Increase

financial resources

Improve

operating

efficiency

Secure capital

funds

Improve student

satisfaction

Advance student

success and

graduation rates

Optimize student

learning experience

Create community

partnerships

Develop

community

leaders

Create

distinctive

programs

Strengthen the

Benedictine liberal

arts program

Increase

learning

delivery formats

Strengthen student

support network

Retain qualified

faculty & staff

Support faculty

professional practice

& research

Enhance faculty &

staff development

resources

Strengthen Information

Technology (IT) infrastructure

Build service

learning awareness

& training

department level included expectations that five percent of

nursing faculty would teach in the BLA program and that

service-learning experiences would be offered each semester

at all three levels of the nursing program: sophomore, junior,

and senior. The cascading tool proved useful throughout

the college, especially when used as a basis for developing

and justifying departmental budgets. Budget allocation

could be directly linked to the college’s BSC strategic plan

and subsequent SoN and departmental performance

improvement plans.

Enhance service

learning experiences

Application of the Balanced Scorecard in Higher

Education: Opportunities and Challenges

Planning for Higher Education | Search and read online at: www.scup.org/phe.html 47

Figure 3 Balanced Scorecard Performance Improvement Plan: Undergraduate Department of Nursing

FINANCE

A. Manage enrollment

growth

B. Secure capital funds

STUDENTS AND

COMMUNITY

C. Improve student

satisfaction

INTERNAL PROCESSES

D. Strengthen the

Benedictine Liberal

Arts (BLA) program

E. Enhance student

service-learning

experiences

LEARNING AND

GROWTH

F. Support faculty

professional practice

and research

G. Strengthen

information

technology

infrastructure

SCORECARD

Increase enrollment in

ADEP extended sites and

the three college online

initiatives.

Private donor funding for

capital campaign for

Science building.

Increase students’ overall

satisfaction with their

college experience.

Alignment of BLA program

with mission, vision, and

values of the college.

Increase service-learning

opportunities and student

participation.

Expand faculty development

to support advanced

practice and research.

Provide a competitive

technology infrastructure.

DEPARTMENT LEVEL

Undergraduate Nursing

Increase enrollment in the

online RN to BS program

by 10 percent.

School of Nursing

Identify community

benefactors in the health

care field.

Undergraduate Nursing

One hundred percent of

nursing students report

being satisfied with

availability and variety

of course offerings in

the program.

Undergraduate Nursing

Five percent of nursing

faculty teach BLA courses.

One hundred percent of

nursing students participate

in service-learning

opportunities

Undergraduate Nursing

Nursing faculty funding

sources are available for

advancing education and

research experience.

Integrate nursing

informatics into the

curriculum.

ACTION PLAN

Department Initiatives

1) Develop and revise RN to BS

program for rolling admission,

online format.

2) Nursing faculty training necessary

for successful online courses

implementation.

School of Nursing Initiative

School of Nursing solicits identified

benefactors for capital funds.

Department Initiatives

1) Evaluate nursing elective courses

for the purpose of aligning

offerings with students’ needs.

2) Identify additional ways of meeting

program requirements through a

variety of course or service-learning

opportunities.

Department Initiatives

1) Adjustment of nursing faculty

workload to accommodate

teaching of BLA courses.

2) Nursing faculty representation and

participation in BLA program

planning initiative.

1) Embed service-learning

opportunities in undergraduate

nursing program curriculum.

2) Make service-learning opportunities

available each semester at each

program level: sophomore, junior,

and senior.

Department Initiatives

1) Obtain grant funding to support

nursing faculty education and

research.

2) Offer nursing faculty and student

collaboration experiences to

advance evidenced-based nursing

practice.

1) Advance the use of simulation and

the academic electronic health

record in the curriculum.

2) Increase student didactic and

clinical experiences with nursing

informatics.

This writer agrees with several authors’ assessments

that modification of the BSC is necessary for successful

application in IHEs. As a nursing faculty member, it was

difficult to identify objectives and develop specific performance

measures from a financial perspective. As Mikhail (2004)

suggests, it would have been useful to replace the financial

perspective with a strategic goals perspective. These strategic

goals could be established to support the college’s financial

priorities: to contain costs and to increase enrollment and

revenue in extended campuses and online programs.

Further, future IHE BSC implementations should consider

including the service and outreach perspectives (McDevitt,

Giapponi, and Solomon 2008), especially since these are

congruent with this college’s mission and vision. This

perspective could also be reasonably addressed through

the splitting of the customer perspective into two parts,

with students as one customer and the community as

another, as demonstrated in the strategy map (figure 2).

Recommendations

It would be advantageous for this select liberal arts college

in northern Minnesota to adopt the BSC framework as a

communication tool and strategic management system. Prior

to implementation, it is imperative to name organizational

champions to lead the process, garner support, and gain

the momentum necessary to execute the BSC framework.

These champions should include not only administrators,

but also faculty and staff representatives from the various

schools and administrative departments that support the

college’s academic programs. A valuable resource already

exists in the college’s strategic plan for 2011–2016, which

directly links to the mission and vision of this IHE. The

champions could take the strategic goals found in the plan

and articulate appropriate measures for their attainment

through the development of a BSC that considers all four

perspectives: financial, internal processes, students and

community, and learning and growth.

The SoN could serve as the pilot for implementing the

BSC approach; the SoN is in a position to greatly benefit

from such an approach. Having grown in recent years to

become one of the largest nursing programs in Minnesota,

the school faces challenges in organizing its complex

structure, which is composed of undergraduate programs

taught in traditional, accelerated, and online formats and

graduate programs that include baccalaureate and master’s

degree tracks to doctoral degrees and master’s degree

tracks to five different advanced nursing practice options.

Historically, the SoN’s goals were established without

measurable outcomes and without direct linkages to

departmental budgets. When these goals were revisited at

the end of the academic year, faculty questioned how their

achievement was being measured. While the SoN’s goals

do connect to the college’s mission and vision, nursing

faculty have requested that a long-term strategic plan be

developed to manage the school’s growth and assist in

identifying priorities. Adopting the BSC would enable the

nursing faculty to participate in the identification of SoN

priorities and then, through the BSC improvement plan,

develop school- and department-specific objectives with

performance measure outcomes. The BSC improvement

plan would also establish connections and improve

communication among the four nursing departments and

the school. Clear alignment of performance measurement

indicators with the institution’s mission, values, and strategies

is an imperative in the BSC approach. Further, nursing

education accreditation standards, which have the purpose

of ensuring the quality of baccalaureate and graduate nursing

programs (Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education

2009), mandate that the SoN’s mission, goals, and outcomes

fit with the college’s mission and vision. The BSC improvement

plan can serve as the working document that illustrates the

achievement of this important quality standard.

After successful implementation of the BSC

framework in the SoN, momentum could be maintained by

disseminating the approach to the other schools until the

entire college has adopted the system. Using the college’s

strategy map (figure 2), improvement plans could be

developed by the various schools and departments,

starting with school plans and cascading down to

designated department-level plans. This systematic

approach would help to minimize any difficulty in obtaining

consensus in setting performance measures and would

enhance communication within each school. Moreover,

this process would delineate how each school supports

the college’s mission and values. IHE accrediting

organizations require an institution to demonstrate the

fulfillment of its mission through organizational structure

and system processes. This quality indicator can be

validated through the use of the BSC approach, which

links the college’s mission and values with specific

performance measures in each of the four perspectives

that then cascade down to school and departmental

improvement plans.

Cindy Brown

48 July-September 2012 | Search and read online at: www.scup.org/phe.html

A common issue in IHEs is a disconnect between faculty

and administrators. Communication in IHEs often flows in a

top-down, vertical-type way. Feeling some of these same

sentiments, the faculty at this liberal arts college have

asked for a shared-governance structure. In whole system

shared governance (WSSG), the organizational structure is

decentralized and accountability-based. WSSG “operates

from its core where its mission, vision, and values should

be most visible” (Crow and DeBourgh 2010, p. 216).

Implementation of the BSC framework at this college

would help build relationships among faculty, staff, and

administrators, a start in the process of shared governance.

This writer believes that this college has historically

functioned in a reactive manner. With its emphasis on

continuous improvement processes, the BSC would better

position the college to operate in a proactive mode, since

the scorecard’s lead indicators link college strategies and

mission with measurable outcomes that then drive future

endeavors and initiatives. An efficient and effective way to

gauge and/or predict upcoming trends and issues is

through active engagement and alignment with a variety of

stakeholders; this alignment and engagement is encouraged

with the BSC approach. The college is also challenged by

growth related to distant campuses and online formats,

which may contribute to isolation and inconsistency in

measuring and achieving quality performance standards;

the BSC framework serves to foster connections and build

alignment around key performance indicators.

Conclusion

The BSC framework is an excellent strategy-based

management system that can be used in IHEs to assist

them in clarifying their mission and vision and translating

their vision into strategies. These strategies, in turn, can

serve as the basis for developing operational objectives

or actions with measurable indicators for the purpose of

evaluating performance improvement and achieving success.

In these tumultuous economic times, the use of the

scorecard, with its inclusion of nonfinancial measures,

paradoxically provides IHEs with a way to develop strategic

priorities for resource allocation. Monitoring nonfinancial

measures also affords IHEs the opportunity to consider student

and stakeholder feedback, faculty and staff satisfaction, and

the internal efficiency of the institution’s processes.

The scorecard can serve as an effective communication

tool for IHEs. The BSC approach enhances communication

with internal and external stakeholders; it also provides

a venue for identifying what really matters to these

stakeholders. Improved communication flow builds trust

within and outside the IHE. Since successful execution of

the BSC requires engagement and cooperation among

all levels in the institution, it promotes collaboration and

alignment, which are key motivators in pursuing continuous

quality improvement strategies (Rice and Taylor 2003).

Further, the cascading of the BSC also creates the alignment

of performance measures. With the proliferation of IHE

learning formats to include virtual sites and extended

campuses, decentralization, isolation, and quality control

can be problematic. The collaboration and alignment that

drives the development of BSC performance measures

fosters consistency and motivates action and change at

the institutional level.

References

Asan, S. S., and M. Tanyas. 2007. Integrating Hoshin Kanri and the

Balanced Scorecard for Strategic Management: The Case of

Higher Education. Total Quality Management and Business

Excellence 18 (9): 999–1014.

Beard, D. F. 2009. Successful Applications of the Balanced

Scorecard in Higher Education. Journal of Education for

Business 84 (5): 275–82.

Burke, J. C. 1997. Performance-Funding Indicators: Concerns,

Values, and Models for Two- and Four-Year Colleges and

Universities. Albany, NY: Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute for

Government.

Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education. 2009. Standards for

Accreditation of Baccalaureate and Graduate Degree Nursing

Programs. Washington, DC: Commission on Collegiate Nursing

Education. Retrieved May 2, 2012, from the World Wide Web:

www.aacn.nche.edu/ccne-accreditation/standards09.pdf.

Cribb, G., and C. Hogan. 2003. Balanced Scorecard: Linking

Strategic Planning to Measurement and Communication.

Paper delivered at the 24th Annual IATUL Conference, Ankara,

Turkey, June 2–5. Retrieved May 2, 2012, from the World Wide

Web: http://epublications.bond.edu.au/library_pubs/8.

Application of the Balanced Scorecard in Higher

Education: Opportunities and Challenges

Planning for Higher Education | Search and read online at: www.scup.org/phe.html 49

The BSC framework serves to

build alignment around key

performance indicators.

Crow, G., and G. A. DeBourgh. 2010. Combining Diffusion of

Innovation, Complex, Adaptive Healthcare Organizations, and

Whole Systems Shared Governance: 21st Century Alchemy. In

Innovation Leadership: Creating the Landscape of Health Care

Learning, ed. T. Porter-O’Grady and K. Malloch, 195–246.

Boston: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Gumbus, A. 2005. Introducing the Balanced Scorecard: Creating

Metrics to Measure Performance. Journal of Management

Education 29 (4): 617–30.

Hafner, K. A. 1998. Partnership for Performance: The Balanced

Scorecard Put to the Test at the University of California.

Retrieved May 2, 2012, from the World Wide Web:

http://rec.hku.hk/steve/Msc/reco%206027/handouts

/10-98-bal-scor-chapter2.pdf .

Karathanos, D., and P. Karathanos. 2005. Applying the Balanced

Scorecard to Education. Journal of Education for Business

80 (4): 222–30. Retrieved May 2, 2012, from the World Wide

Web: http://jsofian.files.wordpress.com/2006/12

/applying-bsc-in-education.pdf.

Karpagam, U., and L. Suganthi. 2010. A Strategic Framework for

Managing Higher Educational Institutions. Advances in

Management 3 (10): 15–21.

Lichtenberg, T. 2008. Strategic Alignment: Using the Balanced

Scorecard to Drive Performance. Presentation retrieved from

course lecture notes.

———. 2009. Aligning Performance Through Cascading. Podcast

recorded as part of the

Oregon Office of Rural Health’s Flex Webinar Learning Series,

March 4. Retrieved May 2, 2012, from the World Wide Web:

http://vimeo.com/7298078.

McDevitt, R., C. Giapponi, and N. Solomon. 2008. Strategy

Revitalization in Academe: A Balanced Scorecard Approach.

International Journal of Educational Management 22 (1): 32–47.

Mikhail, S. 2004. The Application of the Balanced Scorecard

Framework to Institutions of Higher Education: Case Study of

an Ontario Community College. Presentation given as part of a

workshop. Retrieved May 2, 2012, from the World Wide Web:

www.ciep.fr/en/confint/conf_2005/doc/intervention/Mikhail.pdf.

Nefstead, W. E., and S. A. Gillard. 2006. Creating an Excel-Based

Balanced Scorecard to Measure the Performance of Colleges

of Agriculture. Paper presented at the American Agricultural

Economics Association Annual Meeting, Long Beach, CA, July

23–26. Retrieved May 2, 2012, from the World Wide Web:

http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/21421/1/sp06ne04.pdf.

Niven, P. R. 2003. Balanced Scorecard: Step-by-Step for

Government and Nonprofit Agencies. Hoboken, NJ: John

Wiley & Sons.

Pineno, C. J. 2008. Should Activity-Based Costing or the Balanced

Scorecard Drive the University Strategy for Continuous

Improvement? Proceedings of ASBBS 15 (1):1367–85.

Retrieved February 24, 2010, from the World Wide Web:

http://asbbs.org/files/2008/PDF/P/Pineno.pdf.

Rice, G. K., and D. C. Taylor. 2003. Continuous-Improvement

Strategies in Higher Education: A Progress Report. Educause

Center for Applied Research Research Bulletin, vol. 2003, no.

20. Retrieved May 2, 2012, from the World Wide Web:

http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ERB0320.pdf.

Ruben, B. D. 1999. Toward a Balanced Scorecard for Higher

Education: Rethinking the College and University Excellence

Indicators Framework. Higher Education Forum 99 (2): 1–10.

Scholey, C., and H. Armitage. 2006. Hands-on Scorecarding in the

Higher Education Sector. Planning for Higher Education 35 (1):

31–41.

Stewart, A. C., and J. Carpenter-Hubin. 2000–2001. The Balanced

Scorecard: Beyond Reports and Rankings. Planning for Higher

Education 29 (2): 37–42.

Cindy Brown

50 July-September 2012 | Search and read online at: www.scup.org/phe.html

CopyrightofPlanningforHigherEducationisthepropertyofSocietyforCollege&

UniversityPlanninganditscontentmaynotbecopiedoremailedtomultiplesitesorposted

toalistservwithoutthecopyrightholder'sexpresswrittenpermission.However,usersmay

print,download,oremailarticlesforindividualuse.