How Do Hub-and-Spoke Cartels Operate?

Lessons from Nine Case Studies

Joseph E. Harrington, Jr.

Patrick T. Harker Professor

Department of Business Economics & Public Policy

The Wharton School

University of Pennsylvania

3620 Locust Walk

Philadelphia, PA 19104

harrij@wharton.upenn.edu

24 August 2018

Abstract

Hub-and-spoke collusion is when …rms in a market coordinate their conduct by

communicating through an upstream supplier or downstream customer. This study

examines nine hub-and-spoke cartels towards understanding how they operate: What

is the collusive scheme? How do …rms achieve mutual understanding regarding that

scheme? What is the role played by the hub? How e¤ective is hub-and-spoke collusion?

The paper also discusses legal approaches to hub-and-spoke collusion.

The research assistance of Hsiang-Yen (Sam) Huang, Asad Hussain, and Sin Chit (Martin) Lai is grate-

fully acknowledged. This research has been supported by a grant from the Carol and Lawrence Zicklin

Center for Business Ethics Research, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

1

1 Introduction

A cartel is a collection of competitors who seek to coordinate their behavior for the purpose of

producing a supracompetitive outcome. Coordination is typically achieved by having cartel

memb ers directly and expressly communicate with each other. As an example, consider the

citric acid cartel. Its …ve members initially met to agree on a market allocation in terms

of market shares, and then regularly communicated to determine prices and exchange sales

data. Over a period of four years, about 25 meetings of the cartel were conducted along

with a dozen or so bilateral meetings between some of the cartel members.

1

Through these

meetings - whether in-person or over the phone - …rms coordinated on a collusive outcome,

monitored for compliance with that outcome, implemented punishments when there was

evidence of noncompliance, and more broadly dealt with the challenges of running a cartel.

While direct communication between cartel members is typical, and would seem to be the

most e¤ective means for delivering a supracompetitive outcome, it is not the only manner

in which colluding …rms share intentions and observations. In a number of cartels, …rms

instead communicated through a third party which had a vertical relationship with them.

Referred to as a hub-and-spoke cartel, the spokes are the colluding competitors and the hub

is an upstream supplier or downstream customer that facilitates collusion by the spokes.

The horizontal agreement among the spokes is referred to as the rim, for it connects the

spokes. Coordination occurs by each spoke communicating with the hub, and the hub

sharing information it has learned from one spoke with the other spokes. While this indirect

communication may be supplemented with some direct communication between the spokes,

the primary avenue for communication is through the hub.

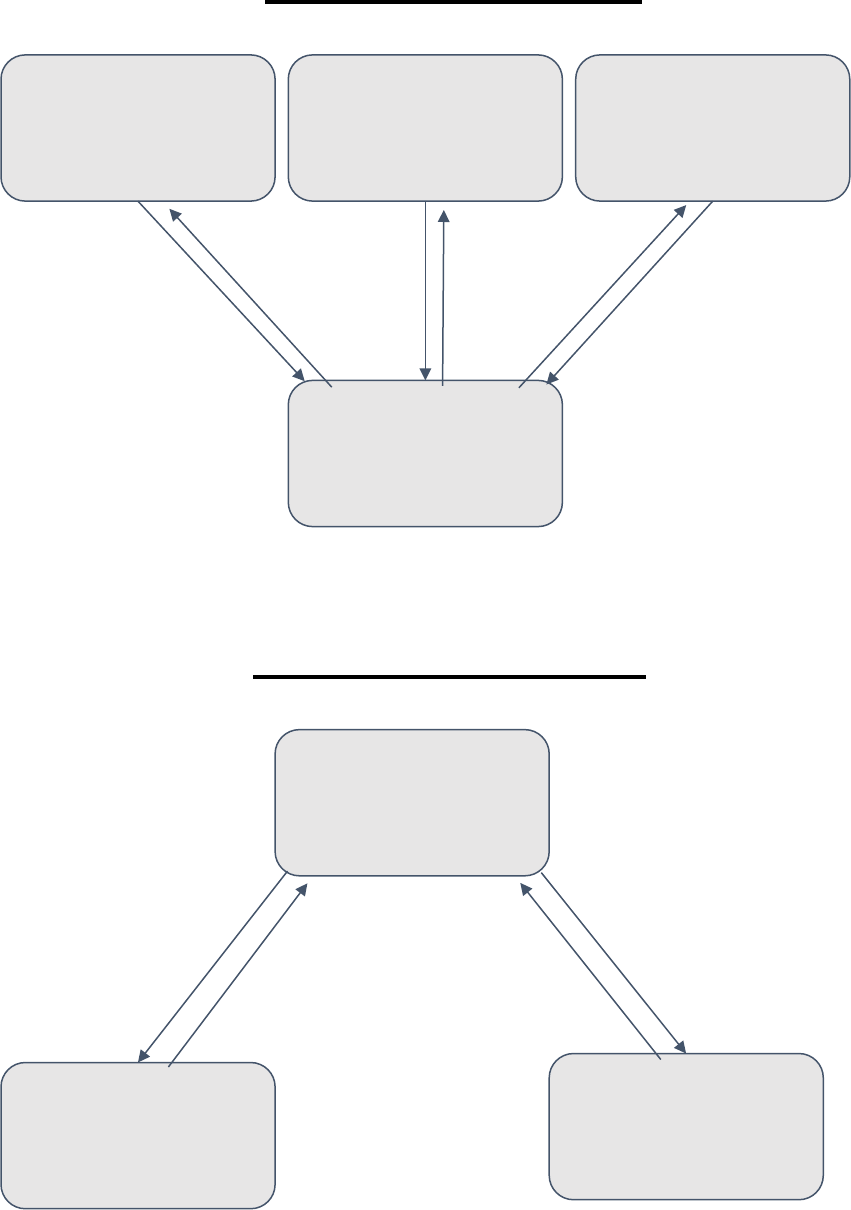

Figure 1 shows two hub-and-spoke cartels in the market for toys. In the U.S. toys case,

downstream toy retailer Toys "R" Us was the hub and upstream toy manufacturers like

Hasbro, Mattel, and Fisher Price were the spokes.

2

Toys "R" Us orchestrated a group boycott

among toy manufacturers against warehouse clubs. So as to achieve mutual understanding

regarding the collusive scheme, each manufacturer learned about the intentions of the other

manufacturers by communicating through Toys "R" Us. In the UK toys case, the roles were

reversed. Upstream toy manufacturer Hasbro was the hub which facilitated collusion among

downstream toy retailers Argos and Littlewoods, who were dominant in the London market.

Argos and Littlewoods never directly communicated about enacting a common price increase

and instead exclusively conveyed their pricing intentions through Hasbro.

The objective of this paper is to investigate hub-and-spoke collusion towards addressing

the following questions: What are the types of collusive schemes implemented by hub-and-

spoke cartels? Given the lack of direct communication, how di¢ cult was it for …rms to achieve

some common understanding? Why did …rms choose to collude through an upstream supplier

or downstream customer? How essential was the hub’s role? How e¤ective was collusion?

To address these questions, the study’s approach is to engage in a series of case studies of

hub-and-spoke cartels. These questions will be asked of each of the hub-and-spoke cartels

1

These details are from Harrington (2006). See that study and Marshall and Marx (2012) for many

examples.

2

The Administrative Law Judge of the Federal Trade Commission concluded that there were 14 toy

manufacturers (spokes) involved. On appeal, the Commission reduced the number to seven, which included

the three companies cited in Figure 1.

2

examined, from which we’ll seek to identify both variation and commonality across these

cartels.

For a case to be included in our study, it must satisfy three criteria. First, there is

compelling evidence that there was collusion (e.g., a conviction). Second, communication

between competitors was primarily through an upstream supplier or downstream customer.

And, third, there is adequate do cumentation for identifying the collusive scheme and the

process by which they coordinated on that collusive scheme. After an extensive search, nine

cases have been found that satisfy these criteria: movie exhibition (U.S.), toys (U.S., UK),

paints and varnishes (Poland), pharmaceutical products (U.S.), replica football kits (UK),

cheese (UK), drugstore, perfumery, and hygiene products (Belgium), and e-books (U.S.). In

spite of the small number of cases (which means any conclusions are highly tentative) and the

usual sample selection bias associated with cartel studies,

3

I believe the study substantively

adds to our understanding of hub-and-spoke collusion.

4

Hub-and-spoke cartels have long been recognized as a phenomenon in economic and

legal circles. Consequently, there have been studies of individual cases which have provided

useful insight. What there has not been is a systematic investigation that seeks to identify

common elements of hub-and-spoke collusion. Odudu (2011), Sahuguet and Walckiers (2013,

2014), Zampa and Buccirossi (2013), Van Cayseele (2014), and Orbach (2016) raise some

of the economic and legal issues regarding hub-and-spoke collusion but do not provide a

comparative analysis of hub-and-spoke cartels towards addressing the questions of this paper.

There is also a small body of theoretical work on hub-and-spoke collusion which includes

Van Cayseele and Miegelsen (2013) and Sahuguet and Walckiers (2017), as well as some

papers motivated by the e-books case (which are referenced later). In contrast, the goal of

this paper is empirical as we assess how hub-and-spoke collusion works in practice.

Let me summarize some of the study’s …ndings. All nine hub-and-spoke cartels were in-

tended to reduce competition in a retail market. To do so, one of two collusive schemes were

deployed: 1) coordinated exclusion by upstream suppliers (spokes) against a rival or class

of rivals to a downstream retailer (hub); and 2) collusive price setting among downstream

retailers (spokes), often through the imposition of a recommended price by the upstream

supplier (hub). When the exclusion strategy was pursued, the downstream hub also threat-

ened exclusion against the upstream suppliers if they did not participate. It is an open

question whether collusion bene…tted or harmed those upstream …rms. When the scheme

instead had downstream …rms jointly raise their prices, the upstream hub purportedly ben-

e…tted in some cases by being able to raise its wholesale prices. In order to achieve mutual

understanding with regards to the collusive scheme, the hub typically engaged in extensive

back-and-forth bilateral communications with the spokes. These communications went well

beyond informing spokes of the scheme, as the hub had to convince each spoke that the other

spokes were planning to participate. The critical and essential role of the hub is very clear.

3

Our sample encompasses discovered and convicted cartels and thus excludes cartels that were not dis-

covered and those which were discovered but the evidence was inconclusive regarding collusion. As a result,

ine¤ective cartels could be undersampled (as they quickly collapsed and avoided discovery) or oversampled (as

their ine¤ectiveness extended to revealing evidence), while e¤ective cartels could be undersampled (as they

were skilled at avoiding detection) or oversampled (as they remained active long enough to be discovered).

4

If the reader is aware of other hub-and-spoke cartels that may satisfy these criteria, I welcome learning

about them.

3

In most cases, it was the hub that initiated collusion. The hub was the key player in both

coordinating on a collusive scheme and monitoring for compliance by the spokes with that

scheme. The hub performed its own monitoring, collected reports from spokes, and then

acted on this information by contacting and working with noncompliant spokes. However,

in spite of all of these e¤orts, hub-and-spoke cartels had relatively short duration compared

to average cartel duration. It appears that this short duration is due to them being more

easily detected than standard cartels.

Section 2 o¤ers an initial assessment of how hub-and-spoke collusion might di¤er from

when …rms collude using direct communication. Section 3 provides the case studies of nine

hub-and-spoke cartels, from which some regularities are distilled in Section 4. Section 5

examines the enforcement of competition law with a focus on how to establish that …rms

have engaged in unlawful hub-and-spoke collusion.

2 An Initial Assessment of Hub-and-Spoke Collusion

E¤ective collusion requires coordinating on a collusive scheme, monitoring for compliance

with that collusive scheme, and, in order to provide incentives to comply, punishment when

there is evidence of noncompliance. The participation in a cartel of an upstream supplier

or downstream buyer that acts as a conduit for messages between …rms can a¤ect all three

dimensions. First, communication may be less e¤ective because it goes through a third

party. Some information may be lost when a spoke’s message is conveyed to the hub who

then passes it along to other spokes. Second, communication may be less e¤ective and the

collusive scheme could be impacted because the third party is not neutral. As the hub has

vertical relations with the spokes, it will be a¤ected by collusion among the spokes and that

could in‡uence the hub’s conduct. Third, the hub may have information and instruments at

its disposal to make monitoring and punishing more e¤ective. Let me brie‡y elaborate on

each of these e¤ects. The case studies will ‡esh them out.

Collusion requires that competitors achieve some level of mutual understanding that they

are constraining competition and how they plan to constrain competition (i.e., the collusive

scheme). In a hub-and-spoke cartel, this mutual understanding is achieved by communicating

indirectly through the hub. Compared to when competitors directly communicate, indirect

communication may be less e¤ective for two reasons. First, messages between spokes may lose

information in the process of going through the hub. Collusion requires each …rm to achieve

some level of trust with the other cartel members so that it is con…dent that they will abide by

the collusive outcome. When involving face-to-face direct communication, it is not just words

that may create that trust; it may be in‡uenced by how the words are expressed (emphasis,

in‡ection, hesitation), facial expressions, eye contact, and body language. Experimental

research has shown that this extraneous information from direct interaction provides useful

cues for cooperation.

5

However, when …rms communicate through a third party, all but the

words are stripped away. In addition to the loss of those facets of messages, errors may be

introduced as the hub may forget to convey something said by a spoke or mistakenly insert

something that a spoke did not say. In short, messages communicated through a hub are apt

5

For example, see Centorrino et al (2015) and Sparks, Burleigh, and Barclay (2016). Manzini, Sadrieh,

and Vriend (2009) o¤ers a novel approach to measuring the signaling value of non-verbal gestures.

4

to b e less informative than when conveyed directly, and that could make it more di¢ cult for

…rms to coordinate on a collusive arrangement.

Second, the hub may intentionally distort messages or otherwise control the conversation

between spokes because it is not a neutral third party.

6

The hub will be impacted by

collusion and has a di¤erent objective than the spokes due to being an upstream supplier

or downstream customer. Hence, even if the hub and spokes all prefer collusion, the desired

form of collusion could di¤er between them. Of course, even with direct communication,

…rms may have an incentive not to tell the truth and try to mislead rival …rms.

7

However, as

competitors’preferences are likely to be more in line with each other than with an upstream

supplier or downstream customer, communication is likely to be less e¤ective with hub-and-

spoke collusion than with direct communications between colluding …rms.

8

Furthermore,

theoretical research has shown that the presence of an intermediary between communicating

parties can only reduce the informativeness of those parties’messages.

9

To elaborate on this second source of message distortion, consider a hub-and-spoke cartel

in which a manufacturer is the hub (e.g., Hasbro), retailers are the spokes (e.g., Argos

and Littlewoods), and the collusive outcome has retailers raise their prices which will then

support a rise in the wholesale price. As is well documented in our case studies, a retailer

is very concerned with avoiding a situation in which it raises its price only to …nd that

other retailers did not did not raise their prices; for such an outcome would cause the

retailer to su¤er a decline in demand and pro…t. Thus, a compliant retailer incurs a cost

for participating in a failed cartel and, critical for the current discussion, this cost is likely

to be more severe for a retailer than it is for the manufacturer. With the manufacturer

undervaluing the risk that the retailers face, it may try to mislead them in order to enhance

the chances of collusion. For example, the manufacturer might tell each retailer that the

other retailers have agreed to raise their prices when they have said no such thing. The

manufacturer bene…ts if this tactic succeeds in inducing all retailers to raise their prices, and

is only modestly harmed (relative to any complying retailers) if it fails. Such an incentive

to mislead could make communication problematic. If the spokes believe the hub is always

inclined to say that all other spokes have agreed to collude (whether or not it is true) then

the hub’s announcements would be uninformative to the spokes; hence, the hub would b e

unlikely to succeed in achieving mutual understanding among the spokes. Or suppose a

retailer communicated to the manufacturer that it would like all retailers to raise prices by

15% but the manufacturer prefers a 10% increase. Given it is the information gatekeeper,

the manufacturer could convey to the other retailers that this retailer’s pricing intention is

to raise price by 10%. More generally, given its strategic position in the communication

6

Examples in which a neutral third party was hired to assist a cartel include a taxi driver for a bidding

ring at stamp auctions (Asker, 2014) and a consulting company, AC Treuhand, for the organic peroxides

cartel (Marshall and Marx, 2012). In those cartels, …rm directly communicated. The role of the third party

was to assist in implementing and monitoring the collusive outcome and organizing meetings among cartel

members.

7

Members of regular cartels often have di¤erent preferences regarding the extent of the price increase,

the type of market allocation scheme, and, of course, the particular market allocation.

8

Crawford and Sobel (1982) prove that the informativeness of messages is reduced when the preferences

of the sender of a message are less aligned with the preferences of the receiver of the message.

9

This result is proven in Ambrus, Azevedo, and Kamada (2013), and holds as long as parties do not

randomize their actions.

5

network, the hub may choose to distort communications between the spokes in order to push

the collusive outcome in a direction that it favors. As we’ll see, there are cases in which the

hub used its position to implement an outcome that bene…tted it and quite possibly harmed

the spokes. In sum, mutual understanding among …rms is expected to be more problematic

when they indirectly communicate because each …rm is not sure what other …rms are saying

and hearing, and the upstream or downstream …rm that is intermediating may have an

incentive to engage in acts of omission or deception.

Thus far, our discussion has focused on how hub-and-spoke collusion is less e¤ective than

the standard cartel. However, there are ways in which the presence of a hub can make

collusion more e¤ective. First, the credibility of a hub’s messages may be enhanced due to

its relations with a spoke which go beyond participating in a collusive arrangement, and

that could act as a countervailing factor to the forces for incredulity just described. From

its previous business dealings with a spoke, a hub may have established some credibility

which it can draw upon. With regards to future business dealings with a spoke, a hub will

want to maintain a reputation for veracity and that will make its messages more credible. In

contrast, direct communications between …rms in a market is not common in a competitive

environment. This means that the members of a standard cartel cannot draw on an existing

reputation and incentives for maintaining an reputation when they communicate with each

other, while an upstream supplier or downstream buyer can do so in the context of a hub-

and-spoke cartel.

Second, as an upstream supplier or downstream customer, the hub may be in a better

position to monitor for compliance. In conducting normal business practices, the hub is regu-

larly communicating with the spokes, whether it is to take orders (in the case of an upstream

supplier) or to place orders (in the case of a downstream buyer). Those interactions provide

opportunities to collect information useful for monitoring. For example, when visiting stores,

it would be easy for an upstream supplier to observe the prices that a retailer is charging

and thus whether it is setting collusive prices. In addition, if the spokes are engaging in their

own monitoring, the hub can collect that information when interacting with the spokes. If

a downstream buyer learns from several upstream suppliers that a particular upstream sup-

plier is deviating, that provides a compelling basis for implementing a punishment against

that upstream supplier. In sum, given its vertical relations with the spokes, the hub is well

situated to observe and collect information relevant to monitoring and, with more e¤ective

monitoring, comes more e¤ective collusion.

Finally, the hub may possess instruments to induce spokes to comply with the collusive

outcome.

10

One instrument is the refusal to sell or buy from a spoke. If the hub is an

upstream supplier, it could threaten to refuse to supply downstream retailers who are un-

dercutting the collusive price. This would help stabilize collusion in two ways. First, the

prospect of foregone pro…t due to not having the supply to sell will help induce retailers to

comply. Second, in response to a retailer undercutting the collusive price, compliant …rms

are inclined to lower their prices to stave o¤ the loss of demand. However, if the deviating

retailer doesn’t have the supply to fully meet the additional demand then the demand loss

to compliant …rms is lessened which could induce them to continue to charge the collusive

price. Analogously, if the hub is a dominant downstream retailer then it could threaten to

10

For a broader discussion on how vertical restraints can aid collusion, see Levenstein and Suslow (2014).

6

refuse to purchase from noncompliant upstream suppliers.

11

A second instrument is the use

of side payments to stabilize collusion. The hub could o¤er monetary transfers to those …rms

that comply - for example, in the form of rebates - which would provide additional incentives

for the spokes to abide by the collusive arrangement. While monetary transfers could occur

between …rms in a regular cartel, they are more likely to create suspicions than if they were

from a supplier or customer.

12

This section has discussed several reasons for expecting hub-and-spoke collusion to op-

erate di¤erently from when …rms directly communicate and do not involve an upstream

supplier or downstream buyer. Let us now turn to examining our nine hub-and-spoke cartels

and assess to what extent they are di¤erent.

3 Cases of Hub-and-Spoke Collusion

Our coverage encompasses nine hub-and-spoke cartels in the markets for movie exhibition

(U.S.), toys (U.S., UK), paints and varnishes (Poland), pharmaceutical products (U.S.),

replica football kits (UK), cheese (UK), drugstore, perfumery, and hygiene products (Bel-

gium), and e-books (U.S.). For each case, I will describe the market, the collusive scheme, the

communication process through which …rms coordinated and monitored, and the disposition

of the legal case.

3.1 Movie Exhibition

The case concerns the distribution and exhibition of motion pictures.

13

The market for the

exhibition of movies included …rst-run theaters where newly released …lms were shown, and

subsequent-run (or second-run) theaters where those same …lms were shown for a lower ad-

mission price at a later date. Interstate Circuit operated 43 theaters and Texas Consolidated

operated 66 theaters, which were a mix of …rst-run and subsequent-run movie houses. The

two chains dominated the cities in which they had theaters, including having a monopoly

position in many of them.

14

As expressed by Interstate to the eight motion picture distributors, the subsequent-run

theaters (not owned by Interstate or Texas Consolidated) were competing too aggressively.

While the …rst-run theaters were showing a single …lm for an admission price of 40 cents,

many subsequent-run theaters were charging a vastly lower price and often showing two

…lms.

11

Let me note that a standard cartel could elicit the assistance of an upstream supplier to enforce a

collusive agreement. For example, in JTC Petroleum Co. v. Piasa Motor Fuels, Inc., 190 F.3d 775 (7th Cir.

1999), six road contractors formed a cartel to rig bids at local government tenders and, in the usual manner,

directly communicated. One of the contractors, JTC, did not abide by the collusive arrangement, so the

cartel enlisted three emulsi…ed asphalt producers to refuse to supply this essential input to JTC. Nevertheless,

most standard cartels do not involve upstream or downstream …rms and thus lack their assistance in making

collusion more e¤ective.

12

An exception is when competing …rms engage in inter-…rm sales as part of normal business practice. Such

sales allowed …rms to consummate transfers in the citric acid, lysine, and vitamins cartels; see Harrington

(2006) and Harrington and Skrzypacz (2011).

13

Interstate Circuit, Inc., et al. v. United States 306 U.S. 208 (1939)

14

Id. at 215.

7

In seventeen of the eighteen independent [subsequent-run] theatres ...the ad-

mission price was less than 25 cents. ... In most of them the admission was 15

cents or less. It was also the general practice in those theatres to provide double

bills either on certain days of the week or with any feature picture which was

weak in drawing power.

15

As this sti¤ competition was eating into admission sales at its …rst-run theaters, Interstate

sought to coordinate the motion picture distributors on a plan to control these independent

subsequent-run theaters. Hence, the movie exhibitor was acting as the hub to the movie

distributors who were the spokes.

A manager of Interstate initially engaged in bilateral communications with each of the

branch managers of the eight distributors. His plan had distributors require subsequent-

run theaters to charge no less than 25 cents for admission and to show only one …lm. If a

distributor did not follow that policy then Interstate threatened not to show the distributor’s

…lms in its …rst-run theaters. Clearly, this plan would bene…t Interstate, as it would raise the

price and lower the quality of rival exhibitors. It is less clear that it would bene…t distributors.

By raising the prices for subsequent-run theaters, more demand would be generated for …rst-

run theaters which had a higher pro…t margin. While that is likely to raise total industry

pro…ts, it is not immediate that the distributors would end up with more pro…ts. It depends

on the relative bargaining positions of the movie exhibitors and the movie distributors. It

is important to note here that the distributors’ participation does not require that they

are collectively made better only. It is su¢ cient that it is in the best interests of a movie

distributor to participate if it believed that the other distributors would participate, and it

believed Interstate’s threat of punishment for noncompliance. Let us consider a distributor’s

incentives to go along with the exclusionary plan.

To begin, a distributor would be unlikely to comply unless it thought that su¢ ciently

many of the other distributors were planning to comply. For suppose instead that most

distributors did allow subsequent-run theaters to show their …lms at an admission price less

than 25 cents. If a distributor went along with Interstate’s scheme and only licensed its …lms

to subsequent-run theaters that charged at least 25 cents, subsequent-run theaters would

choose to exhibit the …lms of other distributors in order to be able to charge a price that was

competitive in the market. Hence, a compliant distributor could lose signi…cant demand if

the other distributors were noncompliant. Furthermore, the credibility of Interstate’s threat

of punishment for noncompliance - not showing the distributor’s …lms in its theaters - would

be put into question if many distributors did not go along. For Interstate may be willing to

go through with that threat against one or a few distributors but it would be very costly for it

to do so with many distributors, as then there would be many …lms it would not be showing

in its theaters. Thus, the credibility of Interstate’s punishment would be put into question

unless a distributor believed many other distributors were to comply. In sum, a distributor

would probably not comply if most other distributors did not comply because it would lose

signi…cant demand, and Interstate’s retaliatory threat would not be credible. However, if

all other distributors complied then a distributor would be at no competitive disadvantage

from complying, and Interstate’s threatened punishment for noncompliance could have been

credible.

15

Id. at 217-8.

8

For Interstate’s scheme to work, it must inform each distributor of its plan and have each

distributor believe that the other distributors were planning to go along with it. For that

purpose, Mr. O’Donnell, the manager of Interstate and Consolidated, sent out a letter to

each of the eight distributors with all of them named as addressees. That letter described the

plan to impose restrictions on Interstate’s competing exhibitors and the threatened response

of Interstate if a distributor did not participate. Here are some relevant excerpts from that

letter:

Interstate Circuit, Inc. will not agree to purchase produce to be exhibited in

its ‘A’ theatres at a price of 40c/ or more for night admission, unless distributors

agree that in selling their product to subsequent runs, that this ‘A’ product will

never be exhibited at any time or in any theatre at a smaller admission price than

25c/ for adults in the evening. In addition to this price restriction, we also request

that on ‘A’pictures which are exhibited at a night admission price of 40c/ or more

- they shall never be exhibited in conjunction with another feature picture under

the so-called policy of double-features. ... In the event that a distributor sees …t

to sell his product to subsequent runs in violation of this request, it de…nitely

means that we cannot negotiate for his product to b e exhibited in our ‘A’theatres

at top admission prices.

16

The letter was followed with bilateral meetings between Mr. O’Donnell and each distributor.

The U.S. Supreme Court viewed the letter as instrumental in achieving mutual under-

standing among distributors.

The O’Donnell letter named on its face as addressees the eight local repre-

sentatives of the distributors, and so from the beginning each of the distributors

knew that the proposals were under consideration by the others. Each was aware

that all were in active competition and that without substantially unanimous

action with respect to the restrictions for any given territory there was risk of

a substantial loss of the business and good will of the subsequent-run and inde-

pendent exhibitors, but that with it there was the prosp ect of increased pro…ts.

There was, therefore, strong motive for concerted action, full advantage of which

was taken by Interstate and Consolidated in presenting their demands to all in

a single document.

17

The Court concluded there was an unlawful agreement in spite of the lack of direct commu-

nication among the movie distributors.

It was enough that, knowing that concerted action was contemplated and

invited, the distributors gave their adherence to the scheme and participated in

it. Each distributor was advised that the others were asked to participate; each

knew that coop eration was essential to successful operation of the plan. They

knew that the plan, if carried out, would result in a restraint of commerce, ...

and knowing it, all participated in the plan.

18

16

See Interstate Circuit, Inc., et al. v. United States 306 U.S. 208, 216 n.3 (1939)

17

Id. at 222.

18

Id. at 227.

9

In sum, Interstate was a case in which collusion was initiated by the downstream (ex-

hibitor) …rm in response to aggressive competition from rival downstream …rms. The col-

lusive plan was exclusionary in that it proposed the upstream (distributor) …rms require

Interstate’s rival …rms to raise their prices and lower their quality as a condition of having

the upstream …rms’products. An upstream …rm would …nd it optimal to go along only if

it believed many other upstream …rms were to do so, which then required the downstream

…rm to achieve mutual understanding of compliance among the upstream …rms. In the ab-

sence of direct communication between the upstream …rms, the downstream …rm sought to

obtain mutual understanding among them by sending a letter with the collusive plan to all

upstream …rms while noting in the letter that it was sent to all upstream …rms. The letter

was supplemented by bilateral verbal communications in order to achieve enough con…dence

among upstream …rms that other upstream …rms were likely to comply. The Court found

the conduct illegal as it went beyond a vertical contract between one upstream …rm and one

downstream …rm. Rather, the downstream …rm sought to have coordinated adoption of the

collusive plan by the upstream …rms. Informing each upstream …rm that the other upstream

…rms were being asked to comply created a horizontal dimension to this conduct, and was

essential for Interstate’s plan to succeed because it would not have been in the interest of an

upstream …rm to comply unless it thought enough other upstream …rms were to do so.

3.2 Toys (U.S.)

The dominant U.S. toy retailer in the early-mid 1990s was Toys "R" Us (hereafter TRU)

with a 20% national market share.

19

In 18 metropolitan areas, its market share ranged

between 35 and 49%, and was over 50% in eight metropolitan areas and Puerto Rico. In the

upstream market, the leading toy manufacturers were Mattel (with a U.S. market share of

18%), Hasbro (17%), Tyco (3.2%), and Little Tikes (2.8%). For most of those manufacturers,

TRU was its most important customer, as it made up 28% of Mattel’s sales, 28% of Hasbro’s,

31% of Little Tikes’, 35% of Fisher-Price’s, and 48% of Tyco’s.

At the time, the retail landscape was disrupted by warehouse clubs which sold at lower

prices than TRU though in a more sparse, less attractive selling environment. Clubs included

Sam’s Club (a division of Wal-Mart with 256 stores in 1992), Pace (a division of Kmart with

115 stores), Costco (100 stores), Price Club (94 stores), and BJ’s Wholesale (39 stores). The

clubs sold fewer toys than TRU though could stock any product of a toy manufacturer. In

addition to selling the same products that were found in TRU stores, the clubs also worked

with toy manufacturers to create specially-packaged pro ducts that sold at a higher total

price but a lower unit price, so they provided better value.

With a gross margin of around 25%, TRU had entered the toy market as the low-price

retailer when compared to department stores (with gross margins of 40-50%) and small toy

stores. It was forced to defend that status against discount department stores like Wal-Mart

19

Facts are from In re Toys "R" Us, 126 F.T.C. 415 (F.T.C. September 25, 1997) (initial Decision, James

P. Timony). (hereafter, Toys "R" Us 1997); Toys "R" Us, Inc. v. FTC, 126 F.T.C. 415 (F.T.C. October

14, 1998) (opinion of the Federal Trade Commission, Chairman Robert Pitofsky) (hereafter, Toys "R" Us

1998); and Toys "R" Us, INC. v. F.T.C., 1999 U.S. 7th Cir. Briefs (on Petition for Review of a Final Order

of the Federal Trade Commission. Opinion of the Commission: Chairman Robert Pitofsky.) (hereafter, Toys

"R" Us 1999).

10

and Kmart, but the clubs were a more serious threat with gross margins of 9-12%.

By 1989, TRU senior executives were concerned that the clubs presented a

threat to TRU’s low-price image and its pro…ts. TRU knew that consumers form

opinions about a store’s relative prices based on a few visible items. TRU referred

to these products as “price image”or “price sensitive”items. ... TRU had already

lowered the prices of these popular items to meet Wal-Mart’s challenge, but the

clubs’marketing strategies threatened to bring prices even lower.

20

As of mid-1992, TRU reported that a warehouse club was within a …ve-mile radius of 238 of

its 497 U.S. stores.

TRU’s concern was that a customer, upon comparing the prices of TRU and a club for

the same item, would learn that TRU’s price was higher; no longer would TRU be seen as

the low-price outlet for toys. One strategic response would have been to lower prices, but

that would have cut into pro…t margins and could have fueled a price war with the clubs.

An alternative path was for TRU to avoid such price comparisons by preventing clubs from

carrying any toy that TRU carried. Of course, implementation of that strategy required the

participation of the toy manufacturers.

In a document drafted around Toy Fair 1993, Greg Staley from TRU’s inter-

national division summarized TRU’s policy as follows: "Our buying is simple -

we will not carry an identical item which is sold to a Warehouse Club. If we …nd

an item in both our assortments and those of a Club, we will discontinue carrying

that item immediately; and we reserve the right to take clearance markdowns to

dramatically accelerate the rate of sale on that item. In summary, the vendor

has to make a choice as to whom he sells an item - either us or them."

21

Thus, the strategy was one of exclusion - harm rival …rms by limiting the products they are

o¤ered by manufacturers. TRU was going to have manufacturers sell to the clubs only those

products that TRU did not stock, and it was going to induce the manufacturers to go along

by threatening not to carry their products.

While TRU would clearly be better o¤ with this collusive plan, what about the toy

manufacturers? If clubs were paying a lower wholesale price than TRU and the increase

in sales from the lower retail price at the clubs was insu¢ cient to o¤set the lower margins

being earned by manufacturers then collusion could be more pro…table for the manufacturers.

However, if the clubs paid the same, or almost the same, wholesale price as paid by TRU

then the manufacturers would be worse o¤ with TRU’s plan due to lower total sales from

excluding the clubs.

While we do not have the data to address the question of whether TRU’s exclusionary

plan made the toy manufacturers better or worse o¤, the documentary evidence reveals that

the manufacturers expressed an appeal to selling to the clubs; it was a source of growing

sales and made them less dependent on TRU. Playskool’s president noted "that his company

could not stop doing business with the clubs, and that in view of the consolidation in the

20

See Toys "R" Us 1998 at 427.

21

See Toys "R" Us, 1997 at 436-7.

11

retail trade it was important for Playskool to have other customers than TRU."

22

If indeed

the toy manufacturers liked having the clubs as an outlet for their products, that would pose

a challenge to TRU getting those manufactures to exclude the clubs.

A second challenge for TRU is that a toy manufacturer was concerned that it would be

at a disadvantage if it restricted its sales to the clubs and many other manufacturers did

not.

The toy companies were afraid of yielding a potentially important new chan-

nel of distribution to their competitors. Small changes in sales volumes have a

signi…cant e¤ect on toy manufacturers’overall pro…ts, and no retail channel other

than the clubs o¤ered similar opportunities for rapid growth. For example, Mat-

tel’s sales volume to the clubs increased by 87% between 1989 and 1991. Much

of this growth was a result of Sam’s emergence as a toy buyer, but sales to BJ’s,

Costco and Pace also increased at a rapid rate. By comparison, Mattel’s overall

sales grew by approximately 10% during this period.

23

Unilaterally restricting sales to clubs was not in the best interests of a toy manufacturer.

As argued above, a co ordinated restriction of sales by toy manufacturers may not have been

in their interests either. What made it sensible for a toy manufacturer to comply with the

collusive plan was TRU’s threat of exclusion if it did not.

While most – if not all – of the toy companies disliked having to choose

between what they saw as two bad options – (1) sell to TRU and restrict club

sales, or (2) sell to the clubs and risk retaliation from TRU – the decision was

made easier by the horizontal agreement which took the sting out of reducing

sales to the clubs. From the manufacturers’point of view, the boycott was the

second-best alternative.

24

An individual toy manufacturer found it better to comply than not, but only as long as other

toy manufacturers complied.

Finally, TRU faced a third obstacle to getting the toy manufacturers on board. It was

unclear how credible was TRU’s threat to cut o¤ purchases from a toy manufacturer if it did

not comply. Doing so would certainly harm TRU in the short run. The credibility of the

threat also hinged on most or all toy manufacturers complying. If all other toy manufacturers

complied, TRU might …nd it optimal to cut o¤ one toy manufacturer in order to establish

the credibility of its threat and keep other toy manufacturers from breaking ranks. However,

if several toy manufacturers did not comply, it would be very costly for TRU not to stock

their toys. Thus, a toy manufacturer could well believe that TRU would punish it for not

complying only if most or all of the other toy manufacturers were complying.

For all of these reasons, TRU’s collusive plan would be implemented by the toy man-

ufacturers only if each believed their rivals had bought into it. Only then would a toy

manufacturer not be at a competitive disadvantage from restricting supply to the clubs and

only then would it …nd TRU’s exclusionary threat to be credible. The toy manufacturers

clearly conveyed the need for assurances that all would be participating.

22

Id. at 448.

23

See Toys "R" Us 1998 at 552.

24

Toys "R" Us, Inc. v. FTC, 126 F.T.C. 415, 585 n.49 (F.T.C. October 14, 1998)

12

Mattel, Hasbro, Tyco, Little Tikes, Fisher-Price and others all wanted to know

how competitors were reacting to TRU. The manufacturers wanted assurances

from TRU that their competitors were subject to the same rule. They informed

TRU that they wanted a level playing …eld to avoid being placed at a competitive

disadvantage.

25

The challenge to TRU was clear: Convince each toy manufacturer that the other man-

ufacturers were going to restrict sales to the clubs. It met this challenge using bilateral

communications with each toy manufacturer and making each aware of its bilateral commu-

nications with rival toy manufacturers. There is no evidence that TRU ever communicated

to them as a group.

[TRU] tried to obtain a coordinated response from manufacturers by assuring

them that they would not be placed at a competitive disadvantage because TRU

was applying its policy to their competitors. ... The manufacturers all were aware

that TRU was communicating its policy to everyone and that uniformity was

contemplated. And everyone knew that without unanimity regular line product

sales to the clubs would recommence.

26

A key early contact was Hasbro, for whom TRU was its biggest U.S. customer.

In the fall of 1990, TRU’s CEO, Charles Lazarus, met with Hasbro’s execu-

tives and told them that the clubs were a threat to TRU because of their low

prices. He said that if Hasbro continued to aggressively supply the clubs ... that

this could a¤ect their business at TRU.

27

TRU went to each major toy manufacturer with a similar pitch, and each was informed that

their rivals were similarly being pressured to restrict sales to the clubs.

During conversations with manufacturers, TRU did not merely announce that

it would refuse to deal with manufacturers selling to the clubs, or inform man-

ufacturers that all manufacturers would be treated equally. Instead, TRU com-

municated the quid pro quo (i.e., I’ll stop if they stop) from manufacturer to

manufacturer.

28

[TRU vice president Roger] Goddu clari…ed that TRU engaged in these con-

versations with all the key toy manufacturing …rms. “We communicated to our

vendors that we were communicating with all our key suppliers, and we did that

I believe at Toy Fair 1992. We made a point to tell each of the vendors that we

spoke to that we would be talking to our other key suppliers.”

29

Furthermore, TRU would use one toy manufacturer’s acceptance to induce others to come

on board with the policy.

25

See Toys "R" Us 1997 at 436-7.

26

Id. at 430.

27

Id. at 432.

28

Id. at 447.

29

See Toys "R" Us 1998 at 555.

13

After Mattel agreed not to sell to the clubs the same products "based on the

fact that competition does the same", TRU told Hasbro that Mattel had agreed.

... Before committing not to sell certain products to the clubs, Little Tikes asked

TRU what its main competitor in the clubs (Today’s Kids) was going to do.

Goddu informed Little Tikes that Today’s Kids "was going to start doing less

business with the warehouse clubs" whereupon Little Tikes committed to restrict

its sales. ... Lazarus and Goddu told Sega that TRU had convinced Nintendo to

stop selling product to the clubs as part of TRU’s e¤ort to convince Sega to do

the same. TRU argued that Sega should stop selling b ecause TRU had convinced

Nintendo to stop.

30

Just before or at Toy Fair 1992, Hasbro’s then western regional sales man-

ager, James Inane, met with [Hasbro CEO] Verrecchia [who] said that he had just

come from a meeting with TRU, that TRU had met with Hasbro’s competitors,

including Mattel and Fisher-Price, and that they had agreed not to sell promoted

products to the clubs. Verrecchia said that because Hasbro’s competitors had

agreed not to sell promoted products, Hasbro would go along with the agree-

ment. Verrecchia told his sta¤ that Hasbro would not sell promoted products to

the clubs and that Hasbro would watch other manufacturers’sales to the clubs.

Hasbro would refrain from selling to the clubs until another manufacturer broke

the agreement.

31

As the FTC referred to it, TRU engaged in "shuttle diplomacy" by

reassuring each toy manufacturer that rivals would fall into line. It was only

after assurances were exchanged that the toy manufacturers, overcoming their

natural inclination to sell through all potential outlets, became willing to discrim-

inate against the clubs. At that point, a "conscious commitment to a common

scheme" was perfected, and a uniform, clearly interdependent, course of conduct

came into being.

32

TRU worked for over a year and surmounted many obstacles to convince the

large toy manufacturers to discriminate against the clubs by selling to them on

less favorable terms and conditions. The biggest hindrance TRU had to overcome

was the major toy companies’ reluctance to give up a new, fast-growing, and

pro…table channel of distribution, and their concern that any of their rivals who

sold to the clubs might gain sales at their expense. TRU’s solution was to build

a horizontal understanding – essentially an agreement to boycott the clubs –

among its key suppliers.

33

While there was some direct communications between the toy manufacturers,

34

it was

rare. The almost-exclusive channel for communication between toy manufacturers was

30

See Toys "R" Us 1997 at 432-4.

31

Id. at 449.

32

See supra note 19, at 586.

33

Id. at 552.

34

"In May of 1992, at a toy manufacturers’conference, Hasbro’s CEO Allan Hassenfeld discussed with

Tyco’s CEO Richard Grey what each company was doing or not doing with respect to the clubs." See supra

note 20, at 450.

14

through TRU, and it achieved the needed mutual understanding among the spokes. The

FTC concluded that many of the toy manufacturers

required assurances that rivals would sell on discriminatory terms to the clubs,

and ... were satis…ed with TRU’s assurances that such uniform policies would

be adopted. Evidence of that exchange of commitments –not necessarily direct

communications among the toy manufacturers but clearly through the interme-

diation of TRU –is present with respect to Mattel, Hasbro, Fisher Price, Tyco,

Little Tykes, Today’s Kids, and Tiger Electronics.

35

However, the job was not done. Even though many toy manufacturers had agreed to

TRU’s plan, they were continuously concerned with possible deviations by rival …rms. In

response, TRU actively monitored the toy manufacturers for compliance, and the toy man-

ufacturers themselves were instrumental in reporting a rival that supplied clubs outside of

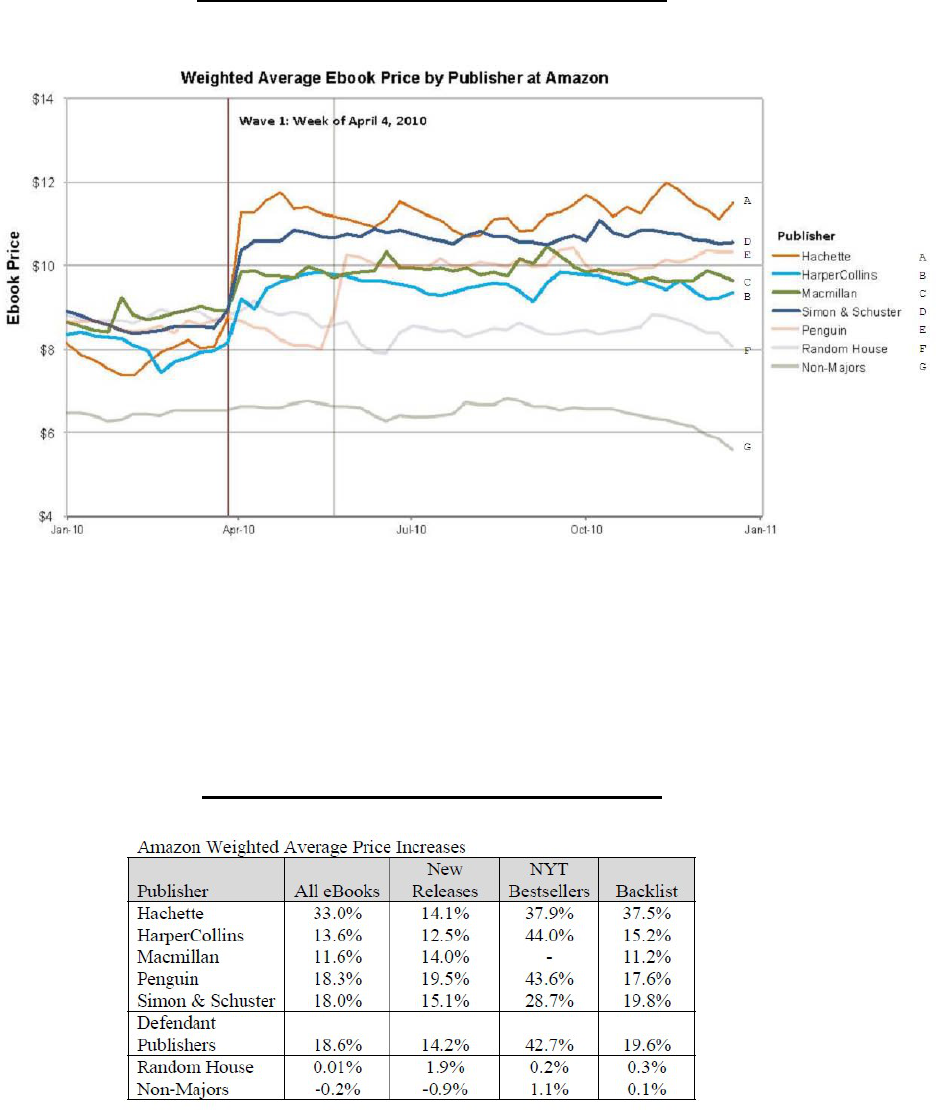

the agreement. Figure 2 provides a list of infractions that was part of a memo to the CEO

of TRU. It states the noncompliant toy manufacturer and the product that was sold to the

clubs, and often o¤ers an explanation for the apparent infraction and a plan to rectify the

conduct.

The toy manufacturers had strong incentives to monitor and share any infractions with

TRU so that rival …rms would be brought into compliance.

[W]hen Mattel heard rumors that Hasbro and Tyco might be selling regular

line to the clubs, the president of Mattel’s Boy Division instructed that the clubs

be shopped and the information sent to TRU.

36

TRU promised to "take care of it" after Fisher-Price representatives com-

plained about Playskool product they found in Price Club.

37

In September 1991, Fisher-Price’s regional manager sent [Fisher-Price sales-

man John] Chase a copy of a TRU shopping report showing products of Hasbro,

Fisher-Price and Playskool found in Price Club. He told Chase that a TRU

executive had sent the report to Byron Davis, Fisher-Price’s vice-president for

sales. The words "Byron, you promised this wouldn’t happen" were written on

the report. After this event, Fisher-Price limited its club sales to special and

combination packs.

38

TRU admitted that it acted as a conduit between …rms regarding complaints of noncompli-

ance.

TRU’s President testi…ed: “I would get phone calls all the time from Mattel

saying Hasbro has this in the clubs or Fisher Price has that in the clubs.... So that

occurred all the time.”Goddu explained that, on the many occasions he received

these calls, he would “always thank them and tell them we would follow up.”...

35

See supra note 19, at 575.

36

See supra note 20, at 431.

37

Id. at 434.

38

Id. at 454.

15

TRU would speak to the o¤ending …rm and even assure the complainant that the

o¤ending …rm would be brought into line. Violations of TRU’s club policy were

thus detected and punished, serving to enforce the horizontal agreement. The toy

companies participated in this exchange of complaints, which was frequent and

continued over lengthy periods, e¤ectively making their competitors’compliance

a part of their agreements with TRU.

39

In sum, TRU had two sources of information to aid in monitoring for compliance with the

collusive scheme. One source was TRU shopping the clubs, and the second was reports from

toy manufacturers.

To sum up, let me utilize the FTC’s succinct synopsis of the case.

The record demonstrates that TRU organized and enforced a horizontal agree-

ment among its various suppliers. Despite TRU’s considerable market power, key

toy manufacturers were unwilling to refuse to sell to or discriminate against the

clubs unless they were assured that their competitors would do the same. To over-

come that resistance, TRU gave initial assurances that rival toy manufacturers

would commit to comparable sales programs; TRU representatives then acted

as the central player in the middle of what might be called a hub-and-spoke

conspiracy, shuttling commitments back and forth between toy manufacturers

and helping to hammer out points of shared understanding; toy manufacturers’

commitments were carefully conditioned on comparable behavior by rivals; and,

after the discriminatory program was in place, TRU and the toy manufacturers

worked out a program to detect, bring back into line, and sometimes discipline,

manufacturers that sold to the clubs.

40

The evidence is compelling that TRU’s collusive strategy of exclusion was e¤ective in

reducing toy manufacturers’ sales to the clubs. Mattel and Hasbro’s sales to the clubs

dropped from $32.5 million in 1991 to $10.7 in 1993.

41

The clubs’share of U.S. toy sales,

which had risen from 1.5% to 1.9% during the pre-boycott years of 1991-92, fell to 1.4% by

1995.

42

TRU’s internal documents revealed that, while the clubs were a competitive threat

as of late 1992, they were not considered as such by 1993:

In December of 1992, TRU included clubs located near TRU stores when it

calculated its [competition] index. TRU explained this decision by noting that

“[w]arehouse clubs have been a strong competitive force this season.”Clubs were

withdrawn from later competition indices in 1993 –after TRU’s club policy was

put into e¤ect – because clubs were then thought to have “no signi…cant . . .

impact on TRU stores.”

43

39

See supra note 19, at 558.

40

Id. at 575.

41

Toys "R" Us 1999 at 18.

42

See supra note 19, at 600.

43

Toys "R" Us, Inc. v. FTC, 126 F.T.C. 415, 539 n.15 (F.T.C. October 14, 1998)

16

The reduced supply of the clubs translated into higher prices for consumers. Products

sold by TRU but not by discounters had margins as high as almost 40%.

44

By expanding

the set of products exclusive to TRU, it would have expanded the set of products for which

it could set a high margin. For 1993, the FTC "found that the elimination of competitive

pressure from the clubs cost consumers as much as an extra $55 million per year on top-

selling products purchased at TRU alone."

45

As another measure of e¤ect, TRU and three

toy manufacturers settled private litigation for $56 million.

46

The Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) ruled that TRU and 14 toy manufacturers had

engaged in a per se violation of Section 5 of the FTC Act. In response to the increased

competition from warehouse clubs, the ALJ noted that "TRU could have announced a uni-

lateral policy by TRU and a refusal to deal with suppliers that did not comply. [T]he

issue is whether TRU went further, entering agreements with each manufacturer."

47

The

ALJ concluded that "TRU orchestrated a horizontal conspiracy among its suppliers [and

t]he major manufacturers knew that TRU was contacting the other manufacturers with the

same prop osal and that concerted action was invited."

48

TRU appealed the ALJ’s decision

to the Commission, which was denied. TRU then appealed that decision to the Seventh

Circuit Court which a¢ rmed the FTC’s decision and, in doing so, viewed the case as more

compelling than Interstate.

The Commission’s theory, stripped to its essentials, is that this case is a

modern equivalent of the old Interstate Circuit decision. ... [T]he TRU case if

anything presents a more compelling case for inferring horizontal agreement than

did Interstate Circuit, because not only was the manufacturers’decision to stop

dealing with the warehouse clubs an abrupt shift from the past, and not only is

it suspicious for a manufacturer to deprive itself of a pro…table sales outlet, but

the record here included the direct evidence of communications that was missing

in Interstate Circuit.

49

In Interstate, the key piece of evidence was the letter sent by the hub (Interstate Circuit) to

the spokes (movie distributors) which indicated that all spokes were receiving it. A spoke’s

inference that other spokes were intending to comply would have only been based on knowing

that the other spokes had received the letter. With Toys "R" Us, there was instead bilateral

verbal communications b etween the hub (TRU) and the spokes (toy manufacturers) which

not only encouraged a spoke to participate but made clear that other spokes were similarly

being encouraged and that some had already agreed to participate.

As in Interstate Circuit, there was an invitation clearly addressed to all of the

participants in the proposed conspiracy. Like the listing of all the …lm distributors

as addressees in the letter sent by Interstate Circuit, TRU, in Goddu’s phrase,

“made a point of telling”its suppliers that its club “policy”was to be extended

44

Id. at 530.

45

See supra note 40, at 30. Scherer (2004) provides some of the economic analysis.

46

Scherer (2004)

47

See supra note 20, at 147.

48

Id. at 162.

49

Toys "R" Us v. FTC, 221 F.3d 928, 935 (7th Cir. 2000)

17

to each and every one of them. Each therefore knew that the others were asked

to make a similar decision.

50

And there was more in Toys "R" Us, for the spokes made clear in their communications

with the hub that their participation depended on the other spokes participating. We then

have express communication by a spoke to the hub that it needed a joint action among

manufacturers. That is something which only could only b e inferred by the hub in Interstate.

3.3 Toys (UK)

The previous two cases had a downstream …rm responding to competition in its market by

recruiting upstream …rms to coordinate on an exclusionary action against rival downstream

…rms. Coordination was achieved through bilateral communications between the downstream

hub and each of the upstream spokes. In Interstate, upstream movie distributors imposed

higher prices and lower quality on the downstream hub’s competitors in the movie exhibition

market, and in Toys "R" Us upstream toy manufacturers limited their product o¤erings to

warehouse clubs that were competing against downstream retailer Toys "R" Us.

We now turn to a more common form of hub-and-spoke collusion: The hub is an upstream

manufacturer or wholesaler, the spokes are retailers, and collusion has the downstream …rms

raising retail prices. Interestingly, the …rst case we’ll consider is the reverse of Toys "R" Us

in that a toy manufacturer is the hub and toy retailers are the spokes.

The setting is the London toy retailing market where the top chains are Argos and

Littlewoods (which is also referred to as Index).

51

A key upstream …rm was Hasbro which

was one of the largest toy and game manufacturers in the United Kingdom. Hasbro learned

in 1998 that retailers were "unhappy with the margins they were receiving on Hasbro’s

branded products."

52

A meeting was held among key Hasbro employees in October 1998 to

develop initiatives to raise margins. As noted by Hasbro Sales Director David Bottomley:

"The listing and pricing initiatives came about as a result of low margins that were a concern

across the entire industry and shared by Argos and Littlewoods."

53

The "pricing initiative" was for retailers to charge the recommended retail price (RRP).

The "listing initiative" was for Hasbro to o¤er rebates to retailers to induce them to con-

tinue stocking certain Hasbro products that were in jeopardy of being removed from a toy

retailer’s o¤erings. The pricing initiative would clearly bene…t retailers. Presumably, the two

initiatives must have bene…tted Hasbro given that it was the …rm responsible for devising

and promoting them. These initiatives were developed by Hasbro employees Ian Thomson

(Account Manager for Littlewoods) and Neil Wilson (Account Manager for Argos). They

were also supported at a senior level by Mike McCulloch, the Head of Marketing and Sales,

and Sales Directors David Bottomley and Mike Brighty.

Our focus will be on the pricing initiative for it was the one that required Hasbro to

achieve mutual understanding between Argos and Littlewoods. While there were other toy

50

See supra note 19, at 586.

51

Ensuring facts are from CA/98/8/2003 Agreements between Hasbro UK Ltd, Argos Ltd & Littlewoods

Ltd …xing the price of Hasbro toys and games, [2004] 4 UKCLR 717.

52

See Argos Ltd & Anor v. O¢ ce of Fair Trading [2006] EWCA Civ 1318 [114].

53

Id. at { 98.

18

retailers in the market, Bottomley of Hasbro felt that "Argos and Littlewoods were key to

the success of the pricing initiative since they were the market leaders - if they could be

persuaded to maintain prices at RRP then other retailers would follow suit."

54

However,

getting both of them to charge the RRP required each being assured the other would do so.

Argos is generally accepted as the price setter and leader in the market.

However, Hasbro considered that Argos would have been very unlikely to make a

commitment to follow Hasbro’s RRPs unless it was reassured that doing so would

not result in its catalogue prices being undercut by those in the Index catalogue

[of Littlewoods]. Littlewoods is the main catalogue competitor to Argos. ...

Argos and Littlewoods monitor, in particular, each others’ prices very closely

and produce regular analyses showing how often each undercuts and is undercut

by the other. Since b oth companies o¤er a price-match guarantee, neither can

a¤ord to have prices that are seriously out of step with the other. It was therefore

necessary to reassure Argos that Littlewoods would also be committed to RRPs.

For its part Littlewoods required the same assurance of commitment by Argos.

55

This concern of mutual compliance was especially acute with their catalog prices. As catalogs

were issued only twice a year, a retailer could …nd itself at a price disadvantage for six months

if it complied with the RRP and the other retailer did not.

Both Argos and Littlewoods were concerned about undercutting by any re-

tailer, but each had a special concern about undercutting by the other. This was

because they were the largest catalogue retailers, directly competing with each

other, and because their retailing formats meant that they both had to commit

themselves to a price for a forthcoming season without knowledge of the other’s

intention except for the previous catalogue which was, by de…nition, out of date.

Further, unlike with ordinary retailers where an agreement to price at X could

be given public e¤ect on the next day or within a very short space of time, any

“agreement”or “understanding”that the other catalogue retailer would price at

an agreed price (say RRP) would not be seen to be implemented until much later

when it would be to o late to change one’s own catalogue.

56

Initially, Hasbro focused the pricing initiative on its core games and Action Man product

line. These were high-volume well-advertised products for which pricing had been particu-

larly aggressive. Starting in late 1998, members of Hasbro’s sales team were speaking with

Argos’ buyers about having retailers price at the RRPs. The initial reaction of the retailers

was not encouraging.

Littlewoods was concerned about the feasibility of Hasbro’s pricing initiative

and in particular expressed doubts about Hasbro’s ability to prevent undercutting

by Argos. Ian Thomson states in his witness statement: "It was at this point

54

Id. at {48.

55

Id. at { 47.

56

Id. at { 96.

19

that Mike McCulloch intimated ... that he had been having discussions with the

major opposition (Argos) and they were of the same opinion i.e. that they could

not agree to the new pricing structure for fear of being undercut. It did need

the agreement of both parties in order for the plan to work, but that if Index

would agree to go along with it then Mike McCulloch, using this knowledge,

was con…dent that he could persuade them to do the same. John McMahon

[of Littlewoods] said that he would play ball and go along with the plan but

if they (Argos) reneged on the deal and did not stick to the retail prices in

their 1999 Autumn Winter Catalogue and he (Index) did, he would be seriously

disadvantaged. If this happened as a result he would do some serious price cutting

in the next Index catalogue launch.

57

Intent on surmounting such skepticism, Hasbro engaged in extensive bilateral communi-

cations with Argos and Littlewoods. The goal was for Argos and Littlewoods to commonly

believe they would charge the RRPs. These communications also involved …nding values for

the RRPs that would be acceptable to both retailers.

Hasbro set the RRPs after separate discussions with Argos, Littlewoods, and

other retailers. ... Argos and Littlewoods then selected, independently from each

other, the Hasbro products they would include in their catalogues. Neil Wilson,

Hasbro’s account manager for Argos, describes how the pricing initiative then

worked in practice: "When I was given the products selected for the catalogue, I

established which were the common products carried by the majority of retailers

(not speci…cally Index) and asked Argos what its price intentions were in relation

to each of these products. I did not do this for products that were not common. I

informed Argos what the Hasbro RRPs for the common products were and asked

them whether any of our RRPs were a problem for them to match. ... Having

determined Argos’pricing intentions and passed these on to the other account

managers within Hasbro, I received information from those account managers

regarding the intentions of other retailers to go with RRPs. I then reverted to

Argos and said, without being speci…c, that it was my belief that the future retail

price of a product would or would not be at the RRP. I told Argos which products

this related to. I never mentioned the name of the retailer who was involved or

quanti…ed exactly the price that retailer would go out at. I simply said to Argos

that it was my belief from what retailers told us that this or that product would

or would not be at the RRP."

58

Neil Wilson of Hasbro was communicating with Argos and Ian Thomson of Hasbro was

communicating with Littlewoods. The two of them shared information with the common

objective of each retailer becoming con…dent that the other retailer would charge the RPPs

on the Hasbro products that they commonly carried.

[David Bottomley states:] "It is incorrect to suggest that Neil and Ian were

acting unilaterally in putting together this proposal: it was based on detailed

57

Id. at { 49.

58

Id. at { 53.

20

discussions and conversations that they had with Argos and Littlewoods about

pricing at RRPs. Each was aware that similar discussions were taking place with

the other and that a big e¤ort was being made to get all retailers to price at RRP."

Neil Wilson states: "Argos were fully aware that the pricing initiative involved

Hasbro talking to other retailers." ... Ian Thomson states: "There was no doubt

that Alan Burgess [Littlewoods’s buyer of boys’toys] knew that I was passing on

to the Argos account handler (Neil Wilson) the contents of our discussion and

that I would con…rm the Argos intentions back to him after Neil had concluded

his discussions with Argos."

59

The O¢ ce of Fair Trading found "no evidence that Argos and Littlewoods spoke directly"

and that "con…dential information was exchanged between them with Hasbro acting as the

…xer or middleman".

60

In spite of the initial concerns of Argos and Littlewoods that the other

would undercut the RRPs and the lack of direct communications between them, Hasbro felt

that they achieved the exchange of assurances required for the pricing initiative to work.

[David Bottomley, Neil Wilson and Ian Thomson made] it clear that there

was an informal agreement, understanding or tacit arrangement whereby Argos

and Littlewoods co-operated with Hasbro by indicating that they would or might

price the particular products in question at or near RRP on the understanding

that the other retailer would also do so, at the same time making it clear again

and again that if the other reneged, the former would immediately respond.

61

Bottomley ... states that "what existed between Hasbro and Argos and Hasbro

and Littlewoods was an understanding that, because of the obvious bene…t to

everyone in the industry, prices would be at or near RRP."

62

While the pricing initiative started on a restricted set of products, it was soon extended

to other categories because, as conveyed in a meeting at Hasbro, "it was crucial that we

maintained retail price stability as far as possible across our key brands so that the initia-

tives could succeed."

63

With the …rst pricing initiative having succeeded, there was cautious

optimism: "Littlewoods’reaction to Hasbro’s proposal was similar to Argo’s reaction: it was

positive, but also concerned about undercutting."

64

Argos’senior buyer Sue Porritt "felt it

was great that Hasbro could help maintain retail price stability, but said that Argos would

react if it was undercut in order to remain competitive."

65

Obtaining a state of common understanding among retailers to implement the proposed

collusive strategy was just the starting point to success. A retailer continued to be concerned

that its rival would undercut the RRPs, in spite of its announced intention to abide by them

(as conveyed by Hasbro). To ensure compliance as well as maintain retailers’con…dence in

the scheme, Hasbro monitored the retailers’prices. This issue arose at the very …rst Hasbro

meeting on the pricing initiative.

59

Id. at { 97.

60

Id. at { 97.

61

Id. at { 103.

62

Id. at { 140.

63

Id. at { 65.

64

Id. at { 65.

65

Id. at { 65.

21

23 October 1998 meeting - Discussion took place about the listing and the

pricing initiatives (under which Hasbro would try to get retailers to list at RRPs).

Account managers were briefed to undertake audits of toy retailers and if they

found that prices were not at RRPs they were to have conversations with them

to try and persuade them to adopt RRPs.

66

The importance of monitoring was very much recognized by Hasbro.

Hasbro conducted its own monitoring to detect undercutting by retailers. Ian

Thomson states in his witness statement: "The emphasis on price monitoring

now was to ensure that our other customers would fall in line so that Argos

and Index would be con…dent that our plan was working throughout the UK.

This would reduce the risk of them going back to price cutting in the following

catalogues."

67

Given their concerns about having higher prices than rivals, Argos and Littlewoo ds were

also incentivized to monitor. However, rather than directly contact the deviator, they would

inform Hasbro.

Neil Wilson states: "Argos monitored other retailers’ prices. If they found

out that a retailer was not at the Hasbro RRP, they contacted me to …nd out

why there was a di¤erence. When Argos called me about the apparently lower

price of another retailer, they contacted me to see if Hasbro could do something

about it, i.e. get the other retailer to go back to RRP. The understanding was

that if Hasbro could give Argos an assurance that the other retailer would put

the price back up to the RRP, Argos would also remain at the RRP. If not, Argos

would have to make a decision about how it would price the product –usually

by matching the competitor’s price."

68

In response to receiving this information, Hasbro would seek to bring the recalcitrant retailer

into compliance.

Neil Wilson describes the process: "[O]nce I had spoken to Argos, I contacted

the account manager in Hasbro who dealt with the retailer in question. He or

she in turn called the buyer of the retailer who had the lower price. The account

manager sought to …nd out why the price was lower and to persuade the retailer

to go back to the RRP. Often the lower price turned out to be a temporary

promotion, for instance to clear out stock, or a simple mistake, as most retailers

were eager to charge RRPs. I then informed Argos whether we were able to do

anything and either provided the reassurance they sought or said that we could

do nothing. Argos knew that this was the process that was going on."

69

66

Id. at { 45.

67

Id. at { 85.

68

Id. at { 86.

69

Id. at { 90.

22

Hasbro’s coordinating and monitoring practices proved successful.

The Argos and Littlewoods Autumn/Winter 1999 catalogues were the …rst

catalogues for which the Hasbro account managers for Argos and Littlewoods

had applied the [pricing initiative]. When the catalogues were published in July

1999, it became clear to Hasbro that Argos and Littlewoods had priced nearly

all the Action Man products and core games at the levels they had indicated to

Hasbro, normally at Hasbro’s RRPs. This had been very di¤erent in the three

previous catalogues.

70

At a year-end Hasbro meeting in 1999, it was noted that the "retail pricing initiative has

worked."

71

And, as predicted by Hasbro, it was su¢ cient to get Argos and Littlewoods on

board in order for all major London toy retailers to comply. Argos was the price leader and,

with the exception of Littlewoods, the "rest of [the] retailers were price followers."

72

Other retailers would have been able to see easily from the catalogues that

RRPs were being followed. From the statements made by Hasbro employees,

it would seem that other retailers broadly followed Argos/Littlewoods pricing

practices and that as a result there was little deviation from Hasbro RRPs. Mike

McCulloch states: "As far as other retailers [are] concerned, [there was] no need

to communicate; they had bought into [the] initiative, and were happy to follow

Argos price lead."

73

In an email on May 18, 2000, Ian Thomson and Neil Wilson (who were the Hasbro

Business Account Managers for Littlewoods and Argos respectively) shared their pricing

initiative, along with a report of its success, more broadly within Hasbro:

Neil and I have spoken to our respective contacts at Argos and Index and

put together a proposal regarding the maintenance of certain retails within our

portfolio. This is a step in the right direction and it is fair to say that both

Accounts are keen to improve margins but at the same time are taking a cautious

approach in case either party reneges on a price agreement.

74

In response, they received an e¤usive email from Hasbro Sales Director Mike Brighty:

Ian . . . This is a great initiative that you and Neil have instigated!!!!!!!!!

However, a word to the wise, never ever put anything in writing, its highly illegal

and it could bite you right in the arse!!!! suggest you phone Lesley and tell her

to trash? Talk to Dave. Mike

75

70

Id. at { 57.

71

Id. at { 63.

72

Id. at { 55.

73

Id. at { 55.

74

Id. at { 67.

75

Id. at { 73.

23

The O¢ ce of Fair Trading did "bite them in the arse" when they found all three …rms

to have infringed the Competition Act 1998.

Hasbro, Argos and Littlewoods have entered into an overall agreement and/or

concerted practice to …x the price of certain Hasbro toys and games. This over-

all agreement included two bilateral price-…xing agreements and/or concerted

practices which in themselves constitute infringements: one b etween Hasbro and

Argos and the other between Hasbro and Littlewoo ds. The agreements were en-

tered into in 1999 and ... came to an end no earlier than 15 May 2001 and no later

than 14 September 2001. The OFT takes the view that these agreements... had,