Office Of ReseaRch and educatiOn accOuntability

Review Of liteRacy success act: fiRst yeaR implementatiOn

JasOn e. mumpOweR

Comptroller of the Treasury

nOvembeR 2022

linda wessOn

Assistant Director

eRin bROwn

Legislative Research Analyst

Kim pOtts

Principal Legislative Research Analyst

Introduction

Tennessee students have struggled to meet basic literacy standards

Universal reading screeners identify students’ needs

TDOE provides a free universal reading screener to districts

Schools administer screeners and report results to TDOE

Districts and charter schools notify parents and provide interventions when students have reading deciencies

Teacher training focuses on foundational literacy

TDOE provides professional development for current teachers in literacy instruction

Literacy skills instruction training required for teachers to renew or advance their licenses

Literacy skills instruction training developed for high school students pursuing teacher-pathway courses

Districts update Foundational Literacy Skills Plans

Educator preparation programs revise instruction

Revised EPP standards for teaching reading instruction are adopted

EPP reading instruction to focus primarily on foundational literacy skills outlined in standards

New Tennessee reading instruction test is required to be developed by TDOE and provided at no cost

TDOE reports analyze the state’s literacy practices, instructional training, and

affordability of teacher education programs

Key points from preK through grade 5 foundational literacy skills study

Key points from EPP literacy instruction programs and practices in literacy instruction study

Key points from EPP aordability study

TDOE solicited contracts through a competitive process for several requirements of

the LSA

Existing statutory requirements incorporated into the LSA

Conclusions and Policy Options

Appendix A: History of Literacy Initiatives in Tennessee

Appendix B: Tennessee Universal Reading Screener overview

Appendix C: Early Literacy Network School Districts

Endnotes

Contents

3

3

5

5

7

11

13

13

15

16

16

18

18

19

20

20

21

23

23

24

26

27

31

33

35

36

3

Introduction

During its 2021 Special Session on Education, the Tennessee General Assembly passed the Tennessee Literacy

Success Act (LSA), which seeks to ensure that students in early grades are on track to become procient

readers by the end of grade 3.

1

e LSA requires school districts and public charter schools to use foundational literacy skills instruction

with a phonics-based approach for early reading instruction. To ensure that districts provide eective

foundational literacy instruction, the law requires the use of a reading screener to identify when a student

needs help with reading before completing grade 3, requires specic literacy instruction training for teachers,

and sets a deadline for English language arts textbooks and instructional materials in use to be aligned with

Tennessee standards. e LSA requires districts and charter schools to develop foundational literacy skills

plans – describing the time devoted to aspects of core literacy instruction, additional student interventions and

supports, and their use of screeners, instructional materials, and training for teachers – and submit their plans

for state approval every three years.

A

e LSA legislation also requires educator preparation programs to emphasize a phonics-based approach,

aligned with state foundational literacy standards. Finally, the law requires several new reports on the current

status of Tennessee’s early grades literacy instruction and achievement, teacher training on methods to teach

reading, and aordability of teacher training providers.

In 2022, the General Assembly passed a law requiring that the Comptroller’s Oce annually review

the implementation of the LSA and report its ndings to the chairs of the Senate and House education

committees and the State Board of Education (SBE) by November 1

st

of each year.

2

e Oce of Research

and Education Accountability (OREA) has been designated by

the Comptroller to complete this annual review. is report is the

rst such review. A separate annual Comptroller review of district

and charter school foundational literacy skills plans is required by

the LSA. e rst literacy plan review was completed in 2021, and

this report includes the review of plans that districts and schools

updated in 2022.

OREA’s overall review of the rst year’s implementation of the

Literacy Success Act included multiple interviews with Tennessee

Department of Education (TDOE) sta, a review of state

documents, reports, plans, and guides, and a review of relevant

state laws and SBE rules. OREA also contacted educators at a small

sample of school districts and charter schools across the state to

gather their feedback on implementation.

Tennessee students have struggled to

meet basic literacy standards

Low reading scores for Tennessee’s public school students in early

grades has been a long-time concern for the General Assembly. Over

at least the past two decades, legislators have passed laws, often

working with governors and TDOE, in an eort to improve English

language arts (ELA) prociency rates for young readers. Grade 3

A

Although many charter schools are part of traditional districts, they can make independent instructional choices (such as the selection of a universal reading

screener) based on their charter status.

Multiple reviews of the LSA

• The Tennessee Literacy Success Act

requires TDOE, SBE, and Tennessee

Higher Education Commission (THEC),

to study the implementation of the act

and report to the General Assembly by

July 1, 2024.

• A separate public chapter (Public

Chapter 717, 2022) requires OREA to

study and report on the implementation

of the Literacy Success Act yearly,

beginning with this report, due in

November 2022.

• The newly created Tennessee Reading

Research Center, housed in the UT

College of Education, Health, and

Human Sciences, is tasked with

evaluating the impact of the state’s

Reading 360 initiative and analyzing the

implementation of the Literacy Success

Act, as reported in the press release

announcing its launch.

Sources: Public Chapter 3, 2021, 1st Extraordinary

Session; Public Chapter 717, 2022; TDOE March 7,

2022 news release.

4

is considered a pivotal year for students – who need a strong foundational background in reading to progress

in all subjects – but for several years, only about one-third of the state’s 3rd graders have tested procient in

reading. (See Appendix A for a history of Tennessee’s reading initiatives.)

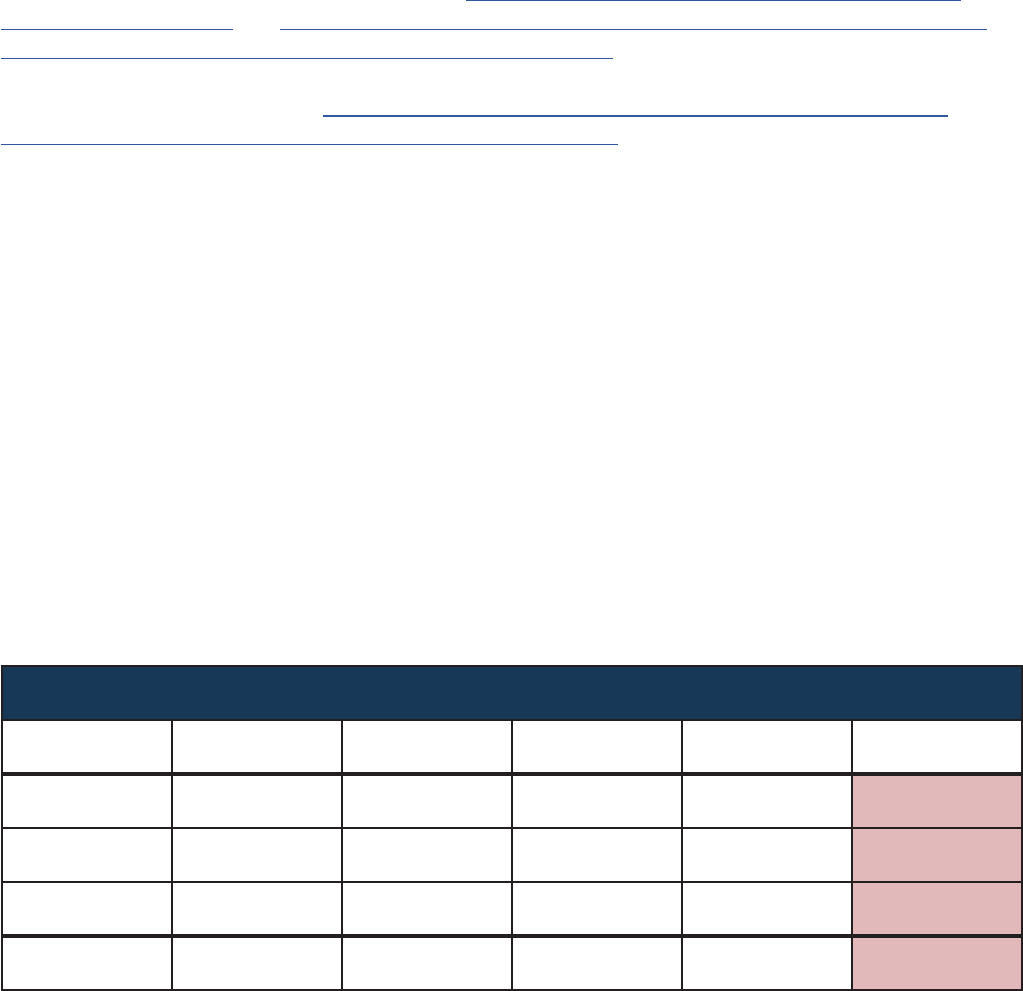

Exhibit 1: The majority of 3rd graders have not shown procient TCAP

reading scores (meets or exceeds expectations) over the last six years

Note: TCAP is Tennessee’s annual standardized student test, the Tennessee Comprehensive Assessment Program. Scores on English language arts are grouped into

four categories: below, approaching, meets, and exceeds grade-level expectations. See more about Tennessee’s literacy initiatives at Appendix A.

Sources: University of Tennessee, Knoxville, A Landscape Analysis of Foundational Literacy Skills in Tennessee, PreK to Grade 5, April 14, 2022; Tennessee Department

of Education, 2022 TCAP Release, June 2022.

Passage of the LSA marks the most targeted attempt by the General Assembly to improve the teaching

of reading in early grades. is review considers the state’s rst year eorts in implementing the LSA’s

requirements, which are designed to ensure that:

• current teachers and teacher candidates are trained to develop students’ foundational literacy skills and

provide appropriate interventions when students need help; and

• educators know how each student in the early grades is progressing toward learning to read.

Foundational literacy skills are the basic building blocks needed to learn to read, including phonemic

awareness (identifying and working with individual sounds in spoken words), phonics (linking sounds of

spoken words with letters), uency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Because research on how students learn

to read has found that a phonics-based approach is most eective, reading instruction based on foundational

literacy skills has been referred to as the “science of reading.”

34.7

36.8

36.9

No TCAP due to COVID

32.0

35.7

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

2016-17 2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

Percent of 3rd graders scoring proficient

Read to be Ready

initiative launched

in Feb. 2016.

Reading 360 initiative

launched in Jan. 2021;

Literacy Success Act

passed in special

session the next month.

5

Universal reading screeners identify

students’ needs

e LSA requires the use of universal reading screeners to ensure that K-3 students are learning the

foundational literacy skills needed for reading and to identify struggling students who need help. All districts

and charter schools are to administer a state-approved universal reading screener to their K-3 students three

times per year beginning in school year 2021-22 and report results to TDOE. Schools are required to notify

parents if the results from the reading screeners indicate a

student has a signicant reading deciency. TDOE made

a free universal reading screener available to districts

and schools beginning in the 2021-22 school year. All

districts and schools have reported their screener results

to TDOE in the rst year of LSA implementation.

TDOE provides a free universal

reading screener to districts

e LSA requires TDOE to provide a free Tennessee

universal reading screener to districts and schools as an

option among other reading screener options approved by

the State Board of Education (SBE).

Districts and schools were rst required to administer

universal screeners in reading, writing, and math to students

in grades K-8 grade in 2014-15 as part of the state’s

adoption of the Response to Instruction and Intervention

(RTI

2

) framework.

3

Universal screeners are short

assessments of foundational skills to help teachers identify

earlier where students may be struggling and provide extra support or interventions for students quickly.

B

Under RTI

2

, districts and schools had some latitude in their choice of screeners, the dates of their

administration, and screener scores that would trigger reading interventions, although TDOE provided

guidance on screeners that met state criteria. e 2021 Literacy Success Act standardized reading screener

implementation for all students in grades K-3 by requiring districts and schools to use one of the state-

approved screeners, requiring screener administration during time periods set by TDOE, and having TDOE

set the screener scores for reading prociency levels, among other changes. Within the choice of approved

screeners, TDOE has specied which subtests (also called “probes”) must be included in each screener

administration and has specied that students’ primary ELA or reading teachers cannot administer the

screeners in order to ensure more objective results.

Screener options

TDOE contracted with NCS Pearson, Inc. to use its aimswebPlus reading screener as the Tennessee universal

reading screener. e Tennessee universal reading screener (TURS) can also be used by districts and schools to

meet RTI

2

and dyslexia screening requirements.

B

In Tennessee, school districts are required to use RTI

2

to identify students with a “specic learning disability.” Specic learning disability is one of 13 federally-

dened disabilities set under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and covers conditions like dyslexia, dyscalculia, and written expression disorder

that aect a child’s ability to read, write, listen, speak, reason, or do math.

What is a universal reading screener?

A universal reading screener is a short, standardized

assessment to check that students are on track in

developing their early reading skills. “Universal”

refers to their administration to all students in a

grade level. Screeners are nationally normed, with

results based on comparisons to other students in

the same grade and school year season. A single

screener is a combination of very short subtests,

each focused on a key skill. Dierent combinations

of subtests are given to students based on their

grade and season. (See Appendix B for more details

on screeners.)

Tennessee contracted with NCS Pearson, Inc. to

make the aimswebPlus reading screener available at

no charge to local districts and charter schools. Each

year of the contract was budgeted at $2.5 million,

using federal funds, and includes several other K-3

screeners, as well as an online reporting platform,

training for district educators, and technical support.

Sources: TDOE interviews, presentations, and guidelines; July 2021

contract with NCS Pearson, Inc.

6

In 2021-22, almost half of districts (48 percent)

used the TURS (aimswebPlus); the other districts

used one or more of the other State Board-approved

screeners.

C

(See Exhibit 2.) Some districts used

two screeners, for example, one for grades K-1

and another for grades 2-3. Charter schools were

most likely to use the MAP screener (36 percent),

followed by Easy CBM (21 percent) and Dibels (18

percent). (See Exhibit 3.)

Districts and schools that decide to change

their screeners must update their state-required

foundational literacy skills plans. Focusing just on

the K-3 universal reading screeners required under

the LSA, 24 districts and six charter schools have

indicated they are changing their screeners for the

2022-23 school year. More districts are planning to

use the TURS or iReady screeners in 2022-23 than

the previous year, and a few charters are shifting to

the TURS as well. (See Exhibits 2 and 3.) (See p. 16 for more on district and charter school updates to their

foundational literacy skills plans.)

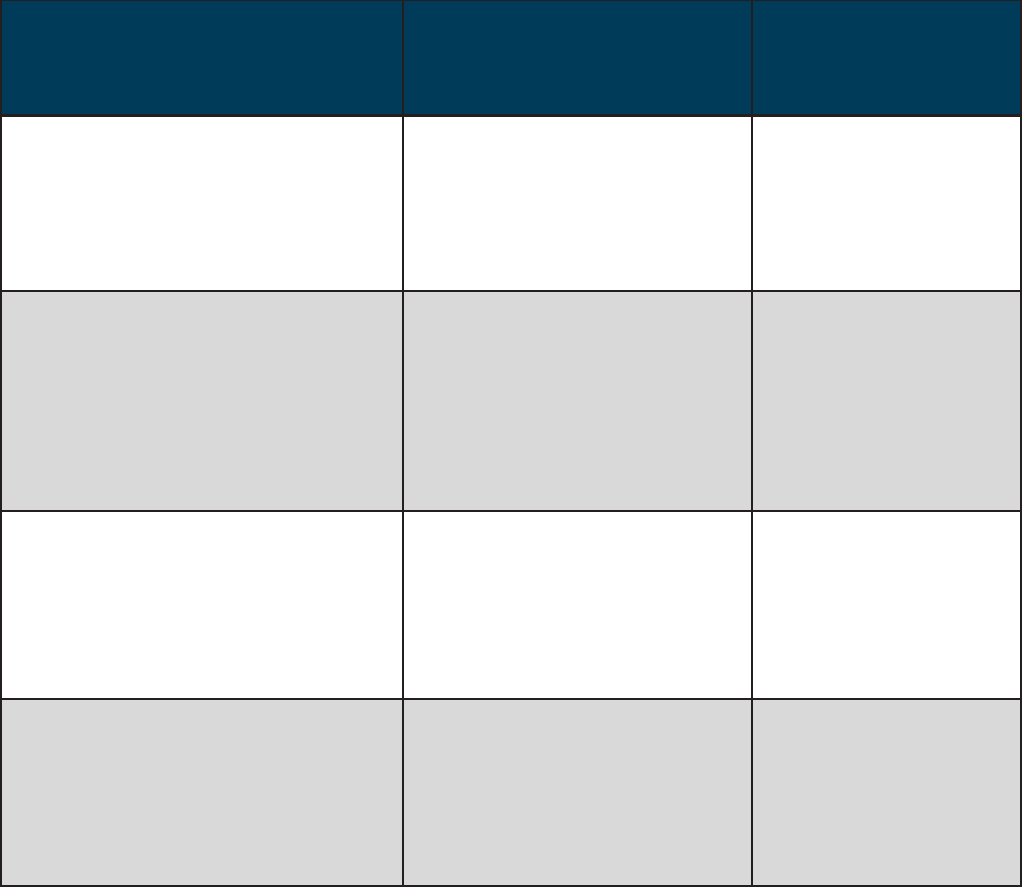

Exhibit 2: Number and percent of districts using approved LSA reading

screeners for K-3 students | 2021-22 and 2022-23

Note: Eleven districts reported using two screeners each in Year 1, and seven districts reported using two screeners each in Year 2 (typically split between grade levels)

for meeting the Literacy Success Act requirements. e dierence from Year 1 to Year 2 in total screeners used explains the results for the Easy CBM screener, in

which fewer districts using it in Year 2 still comprised 18 percent of all screeners used. Districts may use additional screeners for progress monitoring, diagnosing

characteristics of dyslexia, or other purposes.

Source: OREA review of districts’ foundational literacy skills plans.

C

e state special schools were not included in this analysis but those with students in K-3 did administer universal reading screeners.

State Board approved reading screeners

SBE has approved eight universal reading screeners, one

of which has been designated as the Tennessee Universal

Reading Screener, available to districts and schools at no

charge.

• aimswebPlus (designated as the Tennessee Universal

Reading Screener provided by TDOE)

• Dibels 8th edition

• Easy CBM

• Formative Assessment for Teachers (FAST)*

• STAR Early Literacy

• Measures of Academic Progress (MAP)

• Fastbridge Suite*

• iReady Diagnostic for Reading and iReady Early

Reading Tasks

*Since the SBE approval, FAST has been incorporated into

Fastbridge Suite.

Source: State Board of Education Policy 3.302.

3%

3%

6%

11%

11%

18%

48%

2%

2%

5%

7%

14%

18%

53%

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

Dibels

FastBridge/FAST

MAP

STAR

iReady

Easy CBM

aimswebPlus (TURS)

Number of districts using

Reading screener

Year 2: 2022-23 Year 1: 2021-22

7

Exhibit 3: Number and percent of charter schools using approved LSA reading

screeners for K-3 students | 2021-22 and 2022-23

Note: Four charter schools reported using two screeners each in Year 1, and three charter schools reported using two screeners each in Year 2 (typically split between

grade levels) for meeting the Literacy Success Act requirements, Districts may use additional screeners for progress monitoring, diagnosing characteristics of dyslexia,

or other purposes.

Source: OREA review of schools’ foundational literacy skills plans.

Schools administer screeners and report results to TDOE

e LSA requires all districts and charter schools to

report their screener results to TDOE. Typically, the

districts and schools rely on the vendors supplying the

approved screeners for their reporting. e vendors

provide access to digital platforms for schools to record

screener results, and the vendors then submit the screener

results to TDOE.

TDOE reported that all districts and charter schools have

administered the screeners and submitted required data in

compliance with state statute. Screeners are required to be

administered to students during three state-determined

windows. In 2021-22, those windows were:

Fall Aug. 2 – Oct. 1, 2021

Winter Jan. 1 – Feb. 4, 2022

Spring Apr. 11 – May 20, 2022

For 2022-23, some districts noted that earlier communication from TDOE about the scheduled windows

for screener administration and earlier nal conrmation that the windows meet all requirements would be

helpful. Trying to schedule the administration of reading screeners in conjunction with the vendors’ windows,

school vacation breaks, and other assessments is time consuming.

Why all districts do not use the free

reading screener

Because TDOE provides the state’s universal

reading screener for K-3 students to districts at no

charge, some may wonder why all districts do not

use the state’s screener. In interviews with a sample

of districts, OREA heard a variety of reasons. Some

have used other screeners for several years and

teachers are more familiar with them, some districts

want all their grades to use the same screener and

they are already using another screener for grades

outside K-3. Some have multi-year contracts with

other screener vendors or nd other screeners

are better aligned with their curriculum or produce

more useful results. One district tried the state

screener but is switching to another one because

their teachers found the state’s screener too time

consuming and overwhelming.

Source: Interviews with selected school districts and charter schools.

0%

2%

11%

13%

18%

21%

36%

0%

7%

11%

15%

18%

15%

35%

0 5 10 15 20 25

STAR

aimswebPlus (TURS)

FastBridge/FAST

iReady

Dibels

Easy CBM

MAP

Number of charter schools using

Reading screener

Year 2: 2022-23 Year 1: 2021-22

MAP

Easy CBM

Dibels

iReady

FastBridge/FAST

aimswebPlus (TURS)

STAR

8

Screener results

Initial results from the 2021-22 screeners are reported by percentile ranking, based on national norms for

each grade and screener administration period (fall, winter, spring). us, Tennessee’s 1st graders’ scores on

the spring screener, for example, are ranked with other 1st graders’ scores across the country who also took the

same screener test in spring. TDOE sta note that the national norms for the state-approved reading screeners

were all set before COVID; it would therefore be somewhat expected for students who had lost instruction

time during COVID to score lower than students in pre-COVID years.

Exhibit 4: Tennessee students’ rise in average percentile rank from 2021-22

universal reading screener composite scores indicate skill gains based on

national norms

Source: Tennessee Department of Education.

e screener results in Exhibit 4 show that, overall, Tennessee

K-3 students gained the same, or more, foundational reading

skills during the 2021-22 school year as students nationwide. e

national norms for the approved screeners have an average range

from the 40th to 59th percentile (think of the largest portion of

a bell curve, like the shaded area in Exhibit 5), with the national

average at the 50th percentile. Tennessee’s average percentile on the

spring foundational literacy skills composite for all grades, K-3, was

43 on the nationally normed scale, roughly indicated by the red line

in Exhibit 5.

4

As required by the LSA, TDOE determined the “reading prociency

level scores” for all the state-approved universal reading screeners.

e SBE adopted rules that K-3 students who score in the 15th

percentile ranking or below on any of the approved, nationally-

normed screeners is determined to have a “signicant reading deciency.”

5

Students with a score between the

16th and 40th percentiles are at risk for a signicant reading deciency.

6

As of September 2022, TDOE did

not have nal data yet available from the seven screener platforms to report how many Tennessee students fell

into the signicant and at risk reading deciency categories.

38

36

41

43

41

38

44

45

41

40

44

46

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Kdgtn 1st 2nd 3rd

Percentile

Fall Winter Spring

Percentile rankings

Percentile rankings for screener

results are based on comparisons to

national results from other students

who completed the same screener. A

change in percentile ranking means

that a student’s score increased or

decreased more than other students’

scores. A percentile ranking that stays

the same does not mean a student

hasn’t progressed; it means the student

progressed at the same rate as others.

In other words, their place in the

ranking line remains unchanged.

Source: various denitions of percentile rankings.

Kindergarten

9

Specic sets of skills measures

show Tennessee students below the

national average percentile rankings

on the year-end spring results,

despite some improvements in each

grade levels’ ranking during the year.

Exhibit 6 shows specic literacy

skills and grade combinations for

Tennessee students by percentile

rankings against national norms.

Exhibit 6: Selected foundational literacy skills and Tennessee students’

percentile rankings based on national norms for year-end composite screener

results | 2021-22

Source: OREA graph of Tennessee Department of Education data.

TDOE is using the screener data submitted by districts and schools to analyze how Tennessee students’

reading skills are developing over time and how Tennessee students compare with other students nationally.

In partnership with the newly established Reading Research Center, TDOE plans to analyze how districts’

performance on reading screeners connects to districts’ participation in Reading 360 initiatives as well as how

it connects to 3rd grade TCAP (Tennessee Comprehensive Assessment Program) scores.

D

PreK screeners

One condition of the TURS that the department provides free to districts and schools is that it be appropriate

for students in pre-kindergarten through 3rd grade, even though the law only requires districts and schools to

administer a screener for K-3 – the preK screener is optional. A problem with the screener designated as the

TURS (aimswebPlus) arose because the preK screener did not have national norms against which to measure

D

Reading 360 is a comprehensive statewide literacy initiative, funded through $100 million in federal grants and COVID-19 relief funding to provide optional

reading resources to help more students develop strong phonics-based reading skills.

43rd

48th

39th

43rd

National average:

50th percentile

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

K-1: reading readiness 2-3: comprehension K-3: fluency K-3: overall composite

Percentile

Exhibit 5: National average percentile compared

to Tennessee average percentile for K-3 spring

composite screener results | 2021-22

50

th

percentile

43

rd

percentile

Source: OREA graph of TDOE data.

10

student progress. State Board of Education rules require

that state-approved universal reading screeners have

national norms, which the TURS does for grades K-3.

7

State Board rules do not require the universal reading

screeners it approves to have preK versions; that is only

required for the TURS in the LSA.

TDOE’s early guidance to districts and schools in July

2021 stated that it was working with Pearson (the

contracted vendor for aimswebPlus) to “apply existing

kindergarten screeners for preK use.”

8

e department

has indicated that nationally normed preK reading

screeners were limited in availability from vendors

generally.

In 2021-22, only one district reported using the preK

screener, and it had to use the national kindergarten

norms to measure the progress of its preK students.

E

For

the 2022-23 school year, two state-approved reading screeners will have national norms for preK: STAR Early

Literacy and Fastbridge, according to TDOE.

National norms on screeners are used to identify students with “signicant reading deciencies,” a designation

that, by law, triggers parent notications and potential reading interventions for K-3 students, but not for

preK students. (See more about steps taken for students with reading deciencies in the next section on parent

notication.) Because the LSA only requires districts and charter schools to administer a universal reading

screener to K-3 students, those are the only student scores required to be reported to TDOE. It is unclear if

the lack of preK national norms, or the use of adapted kindergarten norms, for preK screener results has an

impact on the usage of TURS as a tool for preK teachers to monitor their students’ progress in gaining literacy

skill or to identify where students need additional instruction.

e lack of national preK norms becomes a thornier issue if the district or school chooses to use students’

TURS screener results for preK teachers’ alternative growth measures in their teacher evaluations, an option

allowed, but not required, under provisions of the LSA legislation. Although other, better-aligned options for

preK teacher alternative growth measures exist, using the TURS preK screener for teacher evaluation purposes

may limit its equity as a growth measure, according to TDOE. (Alternative growth measures are non-TCAP

options for teachers to generate a growth measure based only on their classrooms, rather than using one of the

TVAAS composite measures based on a larger group of students.

F

) Since the one district that used the preK

TURS also opted to use the screener results to generate an alternative growth measure for its preK teachers,

TDOE applied a conversion table to translate kindergarten national norms into appropriate student growth

calculations.

G

TDOE guidance on using screener results to generate alternative growth measures for teachers

stated that because 2021-22 would be the rst year for the process, teachers’ level of overall eectiveness

(LOE) scores would also be calculated with a TVAAS composite growth score. en, only the higher of the

LOE scores (using screener results or using a TVAAS composite) would be used for a nal evaluation score.

E

According to TDOE sta, the district was made aware of the limits of the Tennessee Universal Reading Screener (aimswebPlus) and its lack of national preK norms

prior to the district’s nal decision to use it.

F

All teacher evaluations must include some type of growth score, indicating how much a teacher helped students increase learning. For teachers whose students take

TCAP tests, the TVAAS growth score calculated for a classroom serves as that teacher’s growth score. For teachers whose students are not tested under TCAP, either

due to grade level or subject taught, a variety of TVAAS composite group scores are used as proxy growth measures for the teachers. Alternative growth measures are

options such as the portfolio model or, recently, universal screener results, that provide teachers with growth scores individual to their classrooms that are not based

on TCAP.

G

Each state-approved universal reading screener provides one of three types of growth calculations, typically based on the students’ initial composite score, that can

be used to generate an individualized growth score for a teacher.

Reading Research Center

Partnering with TDOE in some of its analysis of

universal reading screener results is the new

Reading Research Center, opened at the University

of Tennessee Knoxville campus in 2022. The center

is to evaluate and analyze the state’s Reading 360

initiative and its $100 million investment in literacy

supports and grants. The Reading Research Center

was created by TDOE via an interagency agreement

with the University of Tennessee and funded by federal

COVID-19 relief funding for education. Although not

the direct impetus for TDOE’s creation of the center,

a 2000 state law, which included a number of literacy

education provisions, directed the State Board of

Education and the Tennessee Higher Education

Commission, with others to “consider development” of

a university-based reading research center.

Sources: TDOE interviews and March 7, 2022, news release; Public

Chapter 911, 2000.

11

Districts and charter schools notify parents and provide

interventions when students have reading deciencies

Parent notication

Parent notication through district and school home literacy reports began with RTI

2

, similar to the use of

universal reading screeners. e Literacy Success Act required that some standardized components be included

in communications to parents about students’ reading skills development.

e LSA requires home literacy reports to be sent to parents of each student “immediately upon determining

that a student in kindergarten through grade 3 has a signicant reading deciency, based on the results of the

[most recent] universal reading screener.”

9

TDOE guidance also recommends that home literacy reports be

sent to parents of students identied as “at risk” of a signicant reading deciency. e original LSA legislation

required that these literacy reports to parents include not only that their student had a signicant reading

deciency but also must include:

• information about the importance of a student being able to read prociently by the end of 3rd grade,

• reading activities the parents may use at home to help improve their students’ reading prociency, and

• information about the reading interventions and supports that the district/charter school recommend

for their students.

A sample of districts and charter schools contacted by OREA reported that they have continued to send

parents the home literacy reports as they had been under RTI

2

, although typically some adjustments to the

wording of the reports had been made to comply with the law.

Inclusion of 3rd grade retention information

A 2021 amendment to the LSA requires districts to begin

adding information to the home literacy reports in school

year 2022-23 about the state’s revised 3rd grade retention

law.

10

TDOE has provided districts and charter schools with

guidance, including sample letters, on including retention

information in the home literacy report to parents of those

3rd graders whose reading screener scores trigger report

requirements.

e amendment to the LSA, however, is located in a section of

law describing the required elements of home literacy reports

for parents of all students identied with signicant reading

deciencies, including K-2 students as well as third grade

students. It is not clear if the original intent of the law was to require information about retention for more

than 3rd graders' parents.

Parent notication plans through home literacy reports are a required part of the foundational literacy skills

plans that districts and charter schools submit to TDOE every three years. Districts and schools must submit

plan updates if they make changes to key pieces of their literacy programs, but were not required to revise

their plans for the state’s change to home literacy report requirements.

H

H

See more about foundational literacy skills plans and updates by districts and charter schools on page 16.

3rd grade retention law

Another bill, passed in the same 2021 special

session as the LSA, was the Tennessee

Learning Loss Remediation and Student

Acceleration Act, which established mini

camps, summer camps, learning loss bridge

camps, and a state tutor network. Within that

bill were also revisions to state criteria for

retaining 3rd grade students based on their

TCAP scores of the ELA portion of the test,

including options to avoid retention, such as

summer camps and intensive tutoring.

Source: Public Chapter 1, 2021, 1st Extraordinary Session.

12

Interviews with a sample of local districts and schools found that some were still deciding how to provide

information about 3rd grade retention to parents (so they may or may not include the information in all their

home literacy reports); others were planning to provide that information to parents through such avenues as:

• parent nights or parent meetings,

• district-created pamphlets or other materials explaining the law,

• notices that parents must sign and return,

• a strategy of “early and often” communication with parents of 3rd graders, focusing on how parents can

support their students’ progress,

• ensuring that parents know about all available school interventions such as before and after school

tutoring and ALL Corps tutoring,

• family portals where parents can check on their student’s progress, and

• training for principals, who in turn train 2nd and 3rd grade teachers to help prevent the need for retention.

Student interventions and supports

e LSA requires districts and charter schools to provide additional help to students identied as having a

signicant reading deciency. Additional methods of helping with reading – often called interventions and

supports – are detailed in districts’ and schools’ foundational literacy skills plans (FLSPs) and are intended

to get students struggling with literacy skills to get back on track quickly and not fall too far behind. e

LSA states that districts and schools can meet this requirement using the interventions and supports already

outlined in the state’s RTI

2

framework manual.

11

While interventions and supports vary by student needs and by school schedules, policies, and personnel, the

RTI

2

manual outlines the basic steps for intervention:

• universal screeners can identify individual students’ strengths and needs, which in turn can point to

specic skills that may need additional work;

• results from universal screeners can be combined with teachers’ observation of students in class, results

from classroom assignments and tests, and more specialized screenings if needed, to help pinpoint

students’ learning issues;

• depending on the level of intervention, students receive extra instructional time – either in small groups

or individually – that is focused on specic skills, in addition to the core instruction provided to all

students; and

• student performance is regularly monitored to ensure that the intervention is helping the student

progress, with adjustments made if students are not progressing.

TDOE’s Tennessee Foundational Skills Curriculum Supplement – a collection of open-sourced, evidence-

based resources (teacher guides, student workbooks, training, etc.) to help teachers provide foundational

literacy instruction for early grades students – includes specic sample lesson plans, exercises, worksheets, and

other materials for teachers needing to provide supplemental instruction for struggling early readers.

Other interventions that may help students improve literacy skills include after-school programs, summer camps,

and tutoring established as part of the state’s learning loss remediation and student acceleration program.

Information about specic reading interventions and supports that a school recommends for a student and

intervention activities that parents can use at home are required to be provided in the home literacy reports

given to parents of students whose screener results indicate a reading deciency.

13

Teacher training focuses on

foundational literacy

Another way the Literacy Success Act helps ensure that schools focus on foundational literacy skills is through

the requirements for teacher training. e law requires TDOE to develop training courses on literacy skills

instruction for both K-5 teachers and high school students in a teaching-as-a-profession career pathway.

e act also requires all K-5 teachers to complete one literacy skills instruction course approved by TDOE

by August 2023. Finally, although not technically part of the Literacy Success Act, but included in the same

public chapter as the act, is a requirement for K-3 teachers and instructional leaders to complete a literacy

skills instruction course prior to advancing or renewing their existing licenses.

I

TDOE has developed both the training course for teachers and the course for high school students

interested in the teaching profession as required by the act, and indications are that K-5 teachers are

making good progress in meeting the requirement to complete one literacy skills instruction course by

the 2023 deadline.

TDOE provides professional development for current teachers in

literacy instruction

e LSA requires TDOE to develop at least one professional development course that provides training on

how to teach foundational literacy skills to elementary students and to make that course available to K-5

teachers at no cost. Prior to the passage of the act in February 2021, TDOE had already taken steps as part

of its Reading 360 initiative to develop and promote teacher training on foundational literacy skills: issuing

a request for proposal for a vendor to develop two early reading training courses and announcing plans for

classroom materials kits and stipends for teachers who successfully complete the free training. e initiative

used federal funds to oer a wide range of optional resources to school districts, teachers, and families to

support student literacy skills. TDOE has characterized the LSA as the policy framework around which

districts can build their early literacy eorts and the Reading 360 initiative as a comprehensive set of strategies

and supports that districts can use in their eorts.

TDOE awarded TNTP (a nonprot formerly known as e New Teacher Project) an initial $8.06 million,

one-year contract in March 2021, to develop and provide two early grades reading courses with accompanying

instructional materials.

12

e contract, funded through federal pandemic relief dollars, was later expanded

from one year to three, with an additional $8 million added to the maximum approved amount.

13

After a

separate request for proposal was issued in 2022, a contract for secondary literacy skills training was awarded

to TNTP for $9.7 million over two and a half years.

14

e LSA requires all K-5 teachers to complete at least one state-approved course in foundational literacy

skills instruction by August 1, 2023. As of summer 2022, TDOE had approved both the Early Reading

Training Course I and the Secondary Literacy Training Course I to meet the law’s requirement. (See box on

foundational literacy skills instruction training.)

TDOE reported that a total of 25,749 licensed educators completed the Early Reading Training Course I as

of August 22, 2022. Based on the passage rates of the educators who completed the course during the 2021

testing period, almost all educators (99.6 percent) passed the end-of-course assessment.

I

e license renewal requirement applies to all teachers seeking renewal or advancement of licenses with endorsements that authorize them to teach students in grades

K-3, regardless of whether they are actively teaching in those grades. e requirement applies to both practitioner (initial) teacher licenses and professional teacher

licenses. Practitioner licenses must be renewed every four years and professional licenses every seven years.

14

Because the training is open to teachers, reading

interventionists, instructional leaders, and other licensed

personnel across standard, special education, and English

learner classrooms, it is dicult to determine the percentage

of active K-5 teachers who have met the law’s training

requirement.

J

Teachers with elementary endorsements but

who are not currently teaching in a K-5 classroom may

also have completed the training. ere are an estimated

28,000 teachers in standard K-5 classrooms. Administrators

from a sample of school districts and charter schools

contacted by OREA during July and August 2022 reported

that their teachers were largely on track to meet the LSA

training requirement by the deadline of August 2023. Some

were also working to have paraprofessionals and certain

administrators trained.

TDOE has indicated that the newly created Reading

Research Center at the University of Tennessee will compile

all the teacher training data and match it to active K-5

classroom teachers in order to conrm that the statutory

requirement is met by the deadline. Although its evaluation

priorities had not been nalized as of August 1, 2022, the

center is anticipating a project in which it will examine the

relationship between teacher participation in professional

development and student performance. While the proposed

evaluation projects for the center are focused on how

Reading 360 components impact student literacy, the

overlap between the LSA requirements and the Reading 360

initiative could provide the necessary information for the center to draw conclusions about whether all active

K-5 teachers had completed at least one required foundational literacy skills training.

Although the second Early Reading course is not required by the LSA, TDOE has provided incentives to

encourage early grades teachers to complete it in addition to the rst course that is required by the act. As part

of the Reading 360 initiative, K-5 teachers earned a $1,000 stipend for completing both Early Reading courses

(I and II) and K-2 teachers received the stipend and classroom kits of curriculum materials. e training

stipends were funded with federal pandemic relief funds for education. During the 2021 training period,

8,935 educators completed both trainings, and the passing rate for Course II was 99.7 percent, indicating that

approximately 8,908 educators earned the stipends for their approximately 60 hours of training. As of August

2022, another 4,404 educators had completed Course II, for a total of 13,339 who have completed both

courses.

K

TDOE's training satisfaction surveys found more than 97 percent of participants in both training years agreed

or strongly agreed that the training prepared them to better support students in phonics-based instruction.

Several districts contacted by OREA reported that sta have been positive about the training overall, that the

training had resulted in improved instruction, and/or that stipends have been an eective incentive. Some

districts noted that state monitoring of which teachers had completed Course I and allowing districts to pull a

report of completers from the state’s school personnel system (COMPASS) would make compliance easier.

J

TDOE also approved Secondary Literacy Training Course I to meet the law’s training requirements. However, since this training in geared to teachers in grades

5-12 and teacher completion data by grade was not available, and since the law only requires a training course for K-5 teachers, data on completion of the Secondary

Literacy Training Course I was not requested for this report.

K

Educators completing Secondary Literacy Course I and II can also earn the $1,000 stipend.

Foundational literacy skills

instruction training

Early Reading Training Course I – Online,

asynchronous (participants learn on their own

time) training for K-5 educators focused on

research on foundational literacy skills, how

those skills are built into Tennessee standards,

the systematic development of those skills, and

the research behind high-quality instructional

materials. Teachers must pass a multiple choice

assessment. (Approximately 25 hours.)

Early Reading Training Course II – Week-long,

in-person training for K-5 educators typically

oered during summer and focused on how to

implement a foundational literacy curriculum and

instructional materials in planning, preparing, and

providing instruction. Participants must pass the

assessment for Course I before taking Course II.

(Approximately 30 hours.)

Secondary Literacy Training Course I and II –

Similar to the Early Reading Training courses, the

secondary literacy training for teachers in grades

5-12 consists of a one-week online course and a

one-week in-person course. These courses focus

on how reading skills develop and how reading

comprehension is supported by vocabulary

growth with the use of high-quality instructional

materials and alignment with state standards.

Sources: TDOE, Reading 360: Tennessee Early Reading

Training, weeks 1 and 2 overview; TDOE, Request for Proposals

for Secondary Literacy Training, April 15, 2021.

15

Another incentive created by the Reading 360 initiative to encourage teacher training beyond the LSA

requirements is aimed at school districts through the Reading 360 Early Literacy Network. e network is a

TDOE-coordinated eort to provide literacy support grants for districts that achieve certain training goals.

e 95 school districts participating in the network had to ensure that 25 percent of their K-2 teachers

competed both Early Reading Course I and Course II during the 2021-22 training period, and that 60

percent of their K-2 teachers will have completed Course I by June 2023. In return, the participating districts

receive two-year, federally funded grants between $80,000 and $100,000, depending on enrollment, to hire

state-approved vendors that provide direct support, such as coaching or professional development, to preK–2

teachers as they implement the new early literacy instruction. e network also oers additional teacher

professional development, both virtually and in-person, which is also open to non-network districts. (See

Appendix C for a list of Early Literacy Network districts.)

A sample of districts contacted by OREA included several that were members of the Early Literacy Network.

ey reported their participation in the network had been worthwhile, particularly for:

• the classroom walk-throughs, high-quality feedback for teachers, and other work with the grant-funded

vendors, and

• the foundational skills resources, including training and lesson plans.

ose districts contacted that had opted not to participate in the network indicated they found too many

conditions attached to the grant funds or that they believed their teachers had sucient training with existing

resources; they thought more might be overwhelming.

Literacy skills instruction training required for teachers to renew

or advance their licenses

In addition to the professional development requirements of the LSA, the 2021 law also included some new

license renewal requirements for teachers and instructional leaders.

L

Beginning in August 2023, some teachers

and instructional leaders must document that they have completed a state-approved course in foundational

literacy skills instruction.

M

e types of licensing actions subject to this requirement include:

• seeking or renewing an initial license authorizing teaching of K-3 students,

• renewing a professional license authorizing teaching of K-3 students,

• renewing or advancing an instructional leader license,

• holding an active professional teaching license in a reciprocal-agreement state and seeking renewal or

advancement of an initial Tennessee license, and

• holding an active professional instructional leader license in a reciprocal-agreement state and seeking

renewal or advancement of a Tennessee initial instructional leader license.

Similar requirements for those enrolled in educator preparation programs and seeking a new license are

outlined in the next section on literacy instruction changes for educator preparation programs. Teachers

subject to these license requirements are those who have endorsements relating to preK-3 education.

L

Although generally all of Public Chapter 3 of the 1st Extraordinary Session of 2021 is referred to as the Tennessee Literacy Success Act, that name technically refers

only to the provisions in the rst three sections of the public chapter that are codied in Part 9 (TCA 49-1-901 through 49-1-909). Additional provisions impacting

educator preparation providers and educator licenses and alternative growth models for teacher evaluations were included in other sections of the public chapter.

M

e law provides the option for teachers to pass a Tennessee reading instruction test or to complete the literacy skills instruction course. Since the law also requires

all K-5 teachers to complete the course by Aug. 1, 2023, it is assumed that most licensed educators will use documentation of the required course to meet this license

requirement. State Board of Education Policy 5.502 indicates initial practitioner teacher licenses must be renewed within four years and professional teacher licenses

must be renewed within seven years.

16

e law requires that local school districts and charter schools approve professional development points for

at least one literacy skills instruction training completed by teachers. (Professional development points are

required to renew or advance educator licenses.) Early Reading Course I and Secondary Literacy Course I are

approved to meet license renewal requirements.

Literacy skills instruction training developed for high school

students pursuing teacher-pathway courses

High school students who are interested in teaching as a profession may have access to career and technical

education (CTE) courses in either the Teaching as a Profession (TAP) or the Early Childhood Education

pathways. e standards for the CTE courses in these pathways are set by the State Board of Education, as

are standards for any other CTE courses. To meet LSA’s requirement for a new foundational literacy skills

instruction course, TDOE presented its proposal for a new level 4 course – Foundational Literacy Practicum –

for SBE’s rst consideration at its May 20, 2022, meeting. In its work to develop the new course, TDOE also

sought to increase the literacy emphasis of existing TAP courses. SBE voted nal approval of the new course

and the related revisions to existing courses at its July 22, 2022, meeting.

Districts update Foundational Literacy

Skills Plans

Part of the Literacy Success Act includes a requirement that all districts and public charter schools submit

foundational literacy skills plans (FLSPs) and regular updates to TDOE for approval.

15

Although 2022 was

not a required submission year, 65 districts and public charters have submitted a revised FLSP since their

initial submissions in 2021.

N

An FLSP details how a district or charter school plans to

provide foundational literacy skills instruction, reading

intervention, and supports to students identied as having

a signicant reading deciency. e plans are intended to

“demonstrate the eective implementation of foundational

literacy skills instruction” which is to be provided as the

primary form of English language arts (ELA) instruction. e

plans are also required to be posted on TDOE’s website as well

as the district or charter school website.

Each district and charter school plan must cover grades K-5 and include the following six sections:

• the amount of daily time devoted to foundational literacy skills instruction and how that time is utilized,

• ELA textbooks and instructional materials adopted,

• the universal reading screener selected by the district or charter school,

• a description of reading interventions and supports available to students with a signicant reading deciency,

• how the district or charter school intends to notify and engage parents in the student literacy process, and

• how the district or charter school will provide professional development in foundational literacy skills to

K-5 teachers.

N

Counts of FLSP changes here may dier from the earlier report section on universal reading screeners because some districts and schools report their screener

changes for grades K-5 in their FLSPs, but the earlier section focused only on screener changes reported for grades K-3, which are grades for which the LSA requires

districts and schools to administer screeners and report results to TDOE.

LSA requires Comptroller review

The LSA requires districts and charter schools

to submit FLSPs every three years but requires

the Comptroller’s Oce to review the plans

and TDOE’s approval of the plans every year.

This section of the report constitutes the

Comptroller’s second annual review of FLSPs.

Source: TCA 49-1-905 (g)(1) and (6).

17

Districts were required to submit their rst foundational literacy skills plans to TDOE by June 1, 2021.

OREA analyzed how these plans aligned with the guidelines created by the SBE and TDOE in a report that

can be found at Review of Foundational Literacy Skills Plans. Districts are required to submit a revised FLSP

every three years unless the district is making a policy change regarding one of the six required topics on an

FLSP, in which case a revision must be submitted to TDOE when the policy change occurs. Districts may be

exempt from a triennial submission if certain student academic growth criteria are met through the Tennessee

Value-Added Assessment System (TVAAS), a statistical method that measures the inuence of a district,

school, or teacher on the year-to-year growth of students or groups of students.

Forty-four districts and charter schools submitted updated plans to reect policy changes for the 2022-23

school year to TDOE for approval. Twenty-one districts and charters had submitted revisions to their FLSP in

2021, after their initial submissions and before the start of the 2021-22 school year. e most common reason

for a revision was a change in universal screener, accounting for 68 percent of changes in updated FLSPs.

Changes in professional development accounted for the second largest share of changes, with 10 districts, or

16 percent, updating this portion of the plan. Districts made these changes to update timelines of teachers’

participation in the Early Literacy Training courses provided by TDOE or to specify what other training

programs teachers will attend. Five districts made changes regarding instructional materials, either adding or

removing instructional programs. Four districts made changes regarding interventions. TDOE approved all

FLSP updates submitted by districts and schools since their initial plan approvals in 2021.

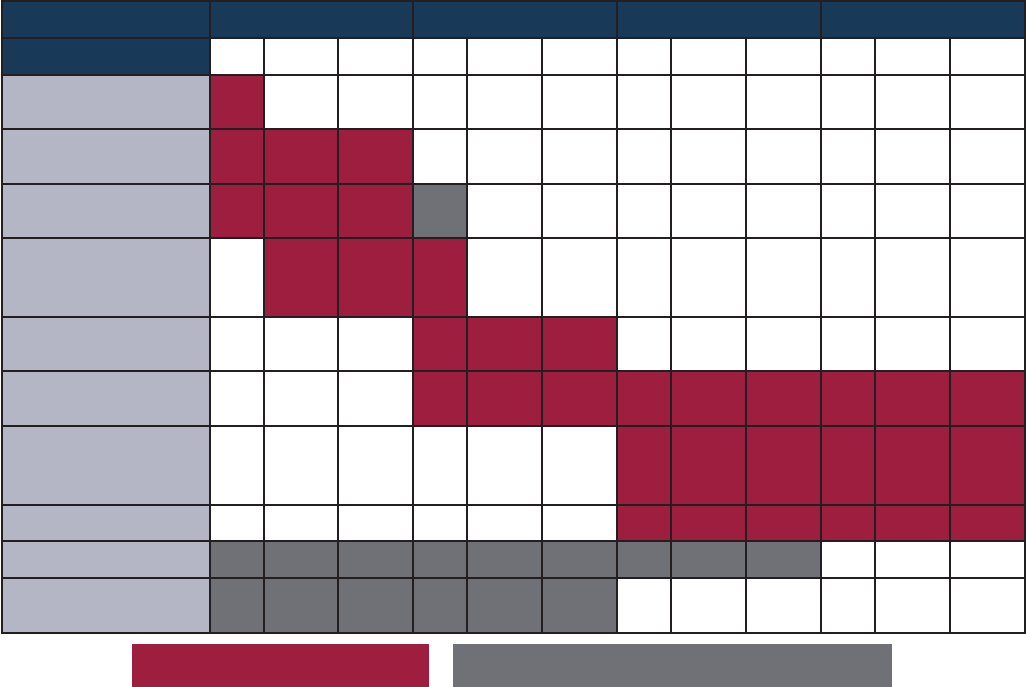

Exhibit 7: Changes to FLSP by type | 2021 and 2022

Note: Districts and schools that submitted updated plans without notable changes in one of the required elements are not included in the graph.

Source: OREA analysis of FLSP updates provided by TDOE.

Parent notication

Professional development

Universal reading screener

Instructional materials

Intervention methods

5 (8.2%)

4 (6.56%)

1 (1.64%)

10 (16.39%)

41 (67.21%)

18

Educator preparation programs

revise instruction

e 2021 law that created the Tennessee Literacy Success Act also included some new requirements for

educator preparation programs (EPPs). EPPs are primarily college programs to prepare students to become

teachers, but also include several alternative programs outside of institutions of higher education, such as

Teach for America and the Memphis Teacher Residency. e law includes three EPP-related requirements:

• TDOE to have developed new foundational literacy skills standards for EPP instruction of candidates

seeking licenses to teach K-3 students and to become instructional leaders by July 31, 2021,

• EPPs to provide reading instruction training primarily focused on foundational literacy skills standards

developed by TDOE beginning August 1, 2022, and

• candidates enrolled in EPPs to pass a state-approved Tennessee reading instruction test or document the

completion of a foundational literacy skills instruction course beginning August 1, 2023.

TDOE has developed, and the State Board of Education has approved, new EPP standards for

instruction of K-3 teacher candidates and instructional leader candidates. EPPs are to begin implementing

the new state literacy instruction standards this school year (2022-23). EPPs must submit plans to TDOE

stating that, beginning with the fall 2022 semester, their reading instruction will have a primary focus on

foundational literacy skills and that courses and clinical experiences will be aligned with foundational literacy

standards. Implementation of the third EPP-related requirement is still in progress. As of July 2022, TDOE

was in the development process for a new Tennessee reading instruction test that certain EPP candidates must

pass as part of their program.

Revised EPP standards for teaching reading instruction are adopted

e law required that by July 31, 2021, TDOE was to develop and submit to the State Board of Education

new foundational literacy skills standards that EPPs would be expected to use in their instruction of

candidates seeking licenses to teach grades K-3 and in specialty program instruction of candidates seeking

instructional leader licenses. e law outlined specic elements to be included in the new literacy skills

standards, including:

• eective teaching of phonemic awareness, phonics, uency, vocabulary, and comprehension;

• dierentiated instruction for students with a range of reading skills;

• identication of and eective teaching for students with dyslexia;

• reading instruction using high-quality instructional materials;

• behavior management, trauma-informed principles and practices, and other supports to ensure students

can access reading instruction; and

• administration of universal reading screeners and use of screener data to improve instruction.

In July 2021, the State Board revised Policy 5.505 addressing literacy and specialty area standards for

educator preparation. e revised policy added new standards for instructional leader preparation programs

and specied that early education foundational literacy skills standards are required in educator preparation

programs that lead to endorsements in:

• early development and learning preK–K,

• early childhood education preK–3,

• integrated early childhood education, birth through K,

• integrated early childhood education preK–3,

19

• elementary education K–5,

• special education early childhood preK–3,

•

• special education comprehensive K–12,

• special education interventionists K–8, and

• special education interventionists 6–12.

Under the law, the standards require training on the components of foundational literacy skills, identication

of students progressing successfully and those who are not, how to respond with appropriate instructional

dierentiation (including instruction for students with dyslexia), identication and use of high-quality

instructional materials, use of universal reading screeners to identify students with reading deciencies, and

trauma-informed instruction and discipline. e revised policy also addresses the new literacy standards for

instructional leader preparation programs, including training on foundational literacy skills, dierentiating

instruction for students at dierent reading levels and those with characteristics of dyslexia, and trauma-

informed practices.

EPP reading instruction to focus primarily on foundational literacy

skills outlined in standards

Beginning in the fall semester of 2022, educator preparation programs approved by SBE are required to base

their reading instruction on the new foundational literacy skills standards adopted by SBE.

O

State Board

Policy 5.504 states that EPPs shall implement all applicable literacy and specialty area standards as set in Policy

5.505.

In addition, after a rulemaking hearing on July 6, 2022, the State Board approved a revision to its rule 0520-

02-04-.07, which outlines requirements for EPPs. e revision adds a new procedure for TDOE to review EPP

alignment to foundational literacy skills standards (per SBE Policy 5.505) and to potentially require corrective

action and, ultimately, denial of approval for any specialty area program that fails to align to and incorporate

the foundational literacy standards. e rule change does not take eect until after review by the Attorney

General and ling with the Secretary of State, and is subject to Government Operations Committee action.

EPP faculty had options to attend Early Reading Training Courses I and II in both 2021 and 2022 when they

were oered to K-5 teachers. A report that reviewed faculty participation in 2021 showed that a majority of

EPP early grades programs had faculty who attended both courses in that year.

16

Finally, EPPs must submit signed assurances to TDOE on how they plan to meet the state requirements to

focus primarily on phonics-based literacy instruction for endorsement areas related to early grades literacy.

Each EPP must explain its plans for how foundational literacy skills standards will be integrated into

applicable programs and demonstrate alignment between literacy standards and the courses and clinical

experiences provided by the EPP. TDOE reviews these assurances in a similar way to its review of districts’

foundational literacy skills plans that outline how they will meet the Literacy Success Act requirements. In its

guidance to EPPs, TDOE has provided several resources and states that

. . .over the course of the next few years, the department will engage substantively with EPPs in

eorts to ensure all EPP faculty and sta who engage in preparing educators in these areas are

adequately prepared and supported.

17

Supports may include program audits with feedback, EPP networking opportunities, and K-12 teacher

training opportunities that will also be open to EPP faculty.

O

EPPs approved by the State Board of Education include both public and private institutions.

20

New Tennessee reading instruction test is required to be

developed by TDOE and provided at no cost

e LSA requires TDOE to develop a new test or identify an existing test that assesses foundational skills

instructional knowledge of candidates for designated teacher or educational leader licenses. e department is

to provide such a test at no cost to the candidate or to the EPP.

TDOE was, as of July 2022, involved in the development process, which may include procurement of

components, for a new Tennessee reading instruction test. Once TDOE develops or identies an appropriate

test, it is to be approved by the State Board. TDOE must also recommend for State Board approval the

passing score that candidates must achieve.

As an alternative to passing the new state-approved foundational literacy instruction test, designated

candidates may document their knowledge of reading instruction by completing the foundational literacy

skills instruction course already developed by TDOE. (See more about the literacy skills instruction course at

p. 14.) e LSA requires that beginning August 1, 2023, candidates who

• seek an initial teaching license or endorsement to teach K-3 students,

• who seek an initial instructional leader license, or

• who have an initial teaching license and are enrolled in a graduate EPP program,

must either pass a state-approved reading instruction test or pass the foundational literacy instruction

course (which includes an end-of-course test). (e law requires this not only of candidates enrolled in EPP

programs, but also of teachers and instructional leaders who already hold a license and are seeking to renew or

advance their existing licenses. See more about training for active teachers at p. 13.)

Typically, candidates enrolled in an EPP and seeking either an Elementary Education K-5 or an Early

Childhood Education preK-3 endorsement would take a Praxis assessment on their content knowledge of

reading instruction (among other content areas), such as “Teaching Reading: Elementary,” as prescribed

in State Board Policy 5.105. e new Tennessee reading instruction test would replace the Praxis reading

instruction test. TDOE states that the Tennessee test will be aligned with Tennessee literacy standards,

unlike the Praxis. e new Tennessee test is expected to be available by the end of the 2022-23 school year.

Alternatively, EPP candidates may document their reading instruction knowledge by completing the free

foundational literacy skills instruction course, which has been available since spring of 2021.

TDOE reports analyze the state’s literacy

practices, instructional training, and

affordability of teacher education programs

e Literacy Success Act of 2021 required TDOE to provide to the State Board of Education and the House

and Senate education committee chairs by March 1, 2022, results of:

• a landscape analysis of literacy in Tennessee, including current practices, student achievement,

instructional programming for students, and remediation services;

• a landscape analysis of literacy instruction, including instructional programming and pedagogical

practices used by educator preparation providers (EPPs); and

• a joint analysis with the Tennessee Higher Education Commission (THEC) about the aordability

of EPPs, including tuition aordability for future educators and costs relative to those in other states;

21

student loan and debt burdens of EPP graduates; nancial barriers that may inhibit people from

pursuing teaching as a profession; and the ability to reduce the costs of obtaining educator preparation

and credentials.

On behalf of TDOE, the University of Tennessee-Knoxville College of Education, Health, and Human

Services published two reports on April 14, 2022: A Landscape Analysis of Foundational Literacy Skills in

Tennessee PreK to Grade 5 and A Landscape Analysis of Tennessee Educator Preparation Providers’ Instructional

Programming & Pedagogical Practices in Foundational Literacy Skills.

In March 2022, TDOE published Educator Preparation Provider Aordability Report: Initial Analysis of

Financial Motivators and Barriers to Becoming a Teacher in Tennessee.

All three required reports have been published. Summaries of the results reported from the three studies follow.

Key points from preK through grade 5 foundational literacy

skills study

e study reviewed English Language Arts (ELA) student achievement data from grades 3 through 5 on the

state assessment (Tennessee Comprehensive Assessment Program or TCAP) from 2017 through 2021. e

achievement data is the baseline for assessing improvements in early literacy prociency that result from

Reading 360, the state reading initiative launched in January 2021.

Generally, grade 3-5 students’ ELA performance increased from 2017 to 2018 and increased or remained

stable from 2018 to 2019 (with a decrease for 4th grade), followed by a decrease between 2019 and 2021, due

to the education disruptions from COVID. Similar trends were found for two subgroups of students: those

that are economically disadvantaged and those who are Black, Hispanic, or Native American.

Exhibit 8: Grades 3-5 students scoring procient in English language arts

dropped in 2021 after COVID disruptions

Note: Data not available for 2020 due to COVID-19-related school closures and state and federal action that authorized a waiver of statewide assessments.

Source: University of Tennessee, Knoxville, A Landscape Analysis of Foundational Literacy Skills in Tennessee, PreK to Grade 5, April 14, 2022, pp. 8-9

e chart below shows ELA performance in 2021 disaggregated by performance level, showing relatively few

students at the top performance level.

Percentage of students whose performance meets or exceeds grade-level expectations

Grade 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Grade 3

34.7% 36.8% 36.9% n/a 32.0%

Grade 4

36.5% 37.9% 34.3% n/a 33.2%

Grade 5

30.8% 32.4% 35.2% n/a 29.0%

Grades 3-5

34.0% 35.7% 35.5% n/a 31.4%

22

Exhibit 9: TCAP ELA performance of grade 3-5 students | 2021

Note: is study was performed before 2022 TCAP results were available.

Source: Based on University of Tennessee, Knoxville, A Landscape Analysis of Foundational Literacy Skills in Tennessee, PreK to Grade 5, April 14, 2022, p. 9.

e analysis found that students’ ELA academic performance in districts and charter schools across the state in

all years reviewed varied considerably. e percentage performing at procient levels ranged from 10.6 percent

to 76.2 percent in 2017 and from 4.5 percent to 72.5 percent in 2021.

e study also analyzed instructional practices in districts and charter schools, based on the foundational

literacy skills plan that each district and charter school is required to submit to TDOE for approval. e

analysis focused on:

• the allocation of time devoted to teaching foundational literacy skills in grades K-2 and grades 3-5;

• types of remediation practices; and

• types of programs and materials used.

e review of district and charter school plans found that:

• All districts and charter schools meet the minimum standards for instructional time – at least 45

minutes in foundational skills instruction in grades K-2 and at least 30 minutes in grades 3-5. e

majority reported spending more than the minimum time in grades K-2, from 45 minutes to 120 or

more minutes, and many reported spending more than the minimum time in grades 3-5, from 30 to

120 minutes.

• Districts and charter schools use a variety of primary instructional materials. Two are used by nearly half

of the districts and charter schools across grades K-5: Amplify – K-5 Core Knowledge Language Arts and

Benchmark – K-5 Advance. e most common supplementary material used is the Tennessee Foundational

Skills Curriculum Supplement.

• All districts and charter schools have a documented process of increasing academic interventions to

students whose academic performance falls below a certain level. e state requires districts to use RTI

2

,

a process of increasingly intensive academic interventions for students whose academic performance falls

under a certain level. Overall, more than 70 dierent RTI

2

interventions were listed in the foundational

literacy skills plans submitted by districts and charter schools for grades K-5.

32.0%

17.6%

30.4%

36.0%

49.2%

40.6%

21.9%

31.0%

26.8%

10.1%

2.2%

2.2%

Grade 3

Grade 4

Grade 5

Below Approaching Met Exceeded

23

Key points from EPP literacy instruction programs and practices

in literacy instruction study

e study is based on a survey of state-approved educator preparation providers (EPPs) that collected

information on each program’s practices, pedagogy (teaching methods), and programming related to

foundational literacy skills instruction.

EPPs provided survey responses about training programs in one or more of three areas:

• early childhood (preK-K and/or preK-3),

• elementary education (grades K-5), and

• special education.

Survey questions focused on:

• the number of courses and credit hours that EPP programs devoted to foundational skills and the

number that incorporate clinical experiences prior to student teaching or teaching internship; and

• how much time EPPs devote to classroom instruction and practical/clinical experience on individual

components of literacy development, as well as broader questions on reading instruction theory and

methods.

e survey found that the science of reading is a strong instructional principle within EPPs’ elementary

education instruction, although some faculty continued to support practices of whole language and balanced

literacy instruction.

e survey also included questions on whether and which faculty (by position) in each EPP program

participated in the TN Early Reading Training Courses 1 and 2 (spring and summer 2021). e survey found

that most EPPs required the training, but some did not. Most EPPs that participated rated the content as

highly eective or very eective. EPPs said the training either strengthened or validated their approaches to

preparing teachers to teach foundational skills.

Key points from EPP affordability study

e context for the study stems from the facts that:

• Tennessee is seeing an overall decline in enrollment in its EPPs, which may relate to aordability.

• Tennessee is in the bottom 10 states in terms of the ratio of public-school teacher wages to wages of

other college graduates.

Two surveys were conducted for the study: one of current, former, and prospective teachers and one of leaders of

Tennessee EPP programs. e study also conducted focus groups and interviews with current and former teachers.

Results from surveys, interviews, and focus groups with current, former, and prospective

teachers

More than two-thirds of the teacher survey respondents have student debt related to their EPP, according

to the teacher survey results. e average debt across all respondents is $36,728, with the second lowest

household income group ($40,000-60,000) incurring the second highest average debt ($40,266).