Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

Before the

Federal Communications Commission

Washington, D.C. 20554

In the Matter of

Applications of

AT&T Inc. and DIRECTV

For Consent to Assign or Transfer Control of

Licenses and Authorizations

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

MB Docket No. 14-90

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

Adopted: July 24, 2015 Released: July 28, 2015

By the Commission: Chairman Wheeler and Commissioners Clyburn and Rosenworcel issuing separate

statements; Commissioner Pai approving in part, dissenting in part and issuing a statement; Commissioner

O’Rielly approving in part, concurring in part and issuing a statement.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Heading Paragraph #

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 1

II. DESCRIPTION OF THE APPLICANTS ............................................................................................ 11

A. AT&T ............................................................................................................................................. 11

B. DIRECTV ...................................................................................................................................... 13

III. THE PROPOSED TRANSACTION .................................................................................................... 15

A. Description ..................................................................................................................................... 15

B. Application and Review Process ................................................................................................... 16

IV. STANDARD OF REVIEW AND PUBLIC INTEREST FRAMEWORK .......................................... 18

V. QUALIFICATIONS OF APPLICANTS ............................................................................................. 24

A. Background .................................................................................................................................... 24

B. DIRECTV ...................................................................................................................................... 25

C. AT&T ............................................................................................................................................. 26

1. Minority Cellular Partners Coalition Comments ..................................................................... 27

a. Standing ............................................................................................................................ 31

b.

Pro Forma Transactions ................................................................................................... 32

c. Notice of Apparent Liability ............................................................................................. 39

d. CALEA ............................................................................................................................. 41

2. New Networks Institute & Teletruth Petition .......................................................................... 45

VI.COMPLIANCE WITH COMMUNICATIONS ACT AND FCC RULES AND POLICIES ............ 52

VII.BACKGROUND ON VIDEO PROGRAMMING DISTRIBUTORS ............................................... 53

VIII.INCREASED MARKET CONCENTRATION IN VIDEO DISTRIBUTION SERVICES ............. 59

IX.HORIZONTAL EFFECTS ANALYSIS ............................................................................................ 82

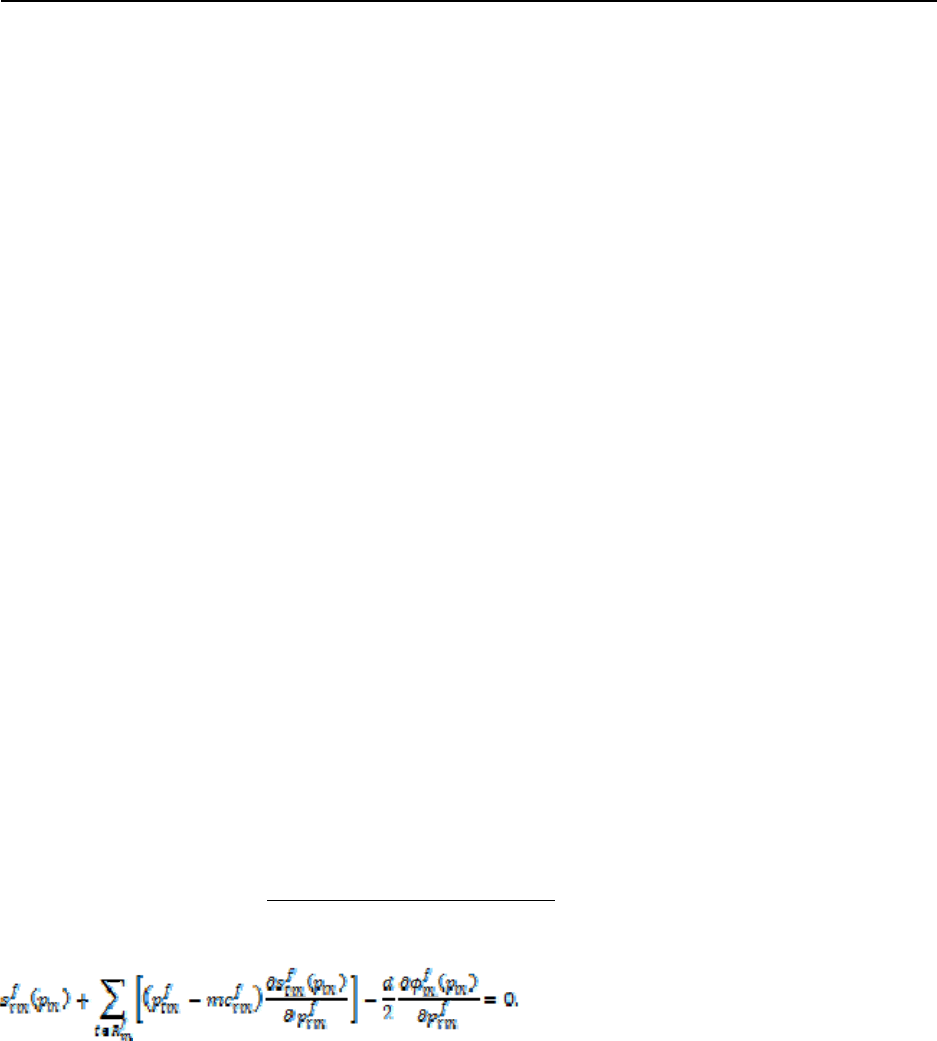

A. Evaluation of Potential Unilateral Effects Using Economic Analysis ........................................... 83

1. Merger Simulation ................................................................................................................... 86

2. BH Simulation Structure and the “Modified Simulation” ....................................................... 91

3. Effects of the Transaction on Consumers .............................................................................. 105

4. Competitive Effects of Integrated Bundles ........................................................................... 111

5. Reduction of Competition in Video Distribution .................................................................. 127

6. Standalone Broadband ........................................................................................................... 134

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

2

B. Documentary and Other Record Evidence of Competition between AT&T and DIRECTV

and the Need for Bundles ............................................................................................................. 146

C. Conclusion ................................................................................................................................... 160

X. ADDITIONAL COMPETITIVE EFFECTS AND PUBLIC INTEREST HARMS RAISED

IN THE RECORD .............................................................................................................................. 161

A. Limits on Competitors’ Access to Programming ......................................................................... 162

1. Limiting Access to RSNs and Other Affiliated Programming .............................................. 163

2. Exclusive Programming Agreements .................................................................................... 177

3. Restricting Access to Online Video Content ......................................................................... 185

4. Forcing Competitors to Compensate Programmers for Reduced Payments from the

Applicants .............................................................................................................................. 188

B. Lack of Regulatory Parity ............................................................................................................ 193

C. Potential Harm to Subscribers’ Access to OVD Services ............................................................ 198

1. Increased Incentive to Discriminate Against Unaffiliated OVDs ......................................... 201

2. Potential Levers for Discrimination Against Unaffiliated OVDs ......................................... 206

a. Data Caps ........................................................................................................................ 208

b. Interconnection ............................................................................................................... 214

D. Harm to Supply, Quality, and Diversity in Video Programming ................................................. 220

1. Background on Video Programming ..................................................................................... 222

2. Potential Competitive Harms ................................................................................................ 225

a. Increased Leverage of Combined Entity in Programming Negotiations ........................ 225

b. PEG Channels ................................................................................................................. 239

c. Local Broadcast Television Stations ............................................................................... 245

E. Video Device Market ...........................................................................................................

........ 249

F. Potential Loss of DIRECTV as a Partner for MDU Broadband Entrants .................................... 255

G. Increased Incentive of Combined Entity to Hinder Competition for Broadband in MDUs ........ 260

H. Increased Incentive of Combined Entity to Hinder Competition in Mobile Wireless

Sector ........................................................................................................................................... 265

I. Increased Incentive and Ability of Combined Entity to Shift Wired Subscribers to FWLL ....... 268

J. Use of Orbit and Spectrum Resources ......................................................................................... 271

XI. ANALYSIS OF POTENTIAL BENEFITS ........................................................................................ 273

A. Analytical Framework ................................................................................................................. 273

B. Improved Bundles ........................................................................................................................ 278

C. Reduced Payments for Programming and Bundling Efficiencies ................................................ 283

1. Reduced Payments for Content Acquisition .......................................................................... 283

2. Other Cost Savings and Efficiencies ..................................................................................... 292

3. Innovation in Video Services ................................................................................................ 295

a. Traditional Video ............................................................................................................ 296

b. OVD ................................................................................................................................ 303

c. Improved Advertising Capabilities ................................................................................. 305

D. Video Programming Market ........................................................................................................ 307

E. Video Device Market ................................................................................................................... 311

F. Expanded Deployment of Fiber to the Premises .......................................................................... 315

1. Analysis of the FIM ............................................................................................................... 327

a. Modification of FIM ....................................................................................................... 328

b. Results from Modifications............................................................................................. 338

2. Non-FIM Factors ................................................................................................................... 342

3. Conclusion ............................................................................................................................. 344

G. Evaluation of Applicants’ Claimed Fixed Wireless Local Loop Benefits ................................... 346

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 346

2. FWLL Coverage and Performance Claims ........................................................................... 348

3. Claims that FWLL Would Benefit 13 Million Rural Customers .......................................... 355

4. Competitive Standalone FWLL and DIRECTV Integrated Bundles Would Be a

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

3

Benefit of the Transaction ..................................................................................................... 358

5. FWLL Deployment is Transaction Specific .......................................................................... 365

6. Conclusion ............................................................................................................................. 376

H. Other Potential Public Interest Benefits ....................................................................................... 378

1. Cybersecurity ........................................................................................................................ 378

2. Diversity Practices ................................................................................................................. 389

3. Labor Practices ...................................................................................................................... 390

XII.REMEDIES ....................................................................................................................................... 392

A. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 392

B. Fiber to the Premises Deployment Commitment ......................................................................... 394

C. Non-Discriminatory Usage-Based Practices ................................................................................ 395

D. Internet Interconnection Disclosure Requirement ....................................................................... 396

E. Discounted Broadband Services for Low-Income Subscribers ................................................... 397

F. Reporting and Outside Compliance Officer ................................................................................. 398

XIII.BALANCING POTENTIAL PUBLIC INTEREST HARMS AND BENEFITS ............................ 399

XIV.CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................................ 400

XV.ORDERING CLAUSES ................................................................................................................... 401

APPENDIX A – List of Licenses to be Transferred

APPENDIX B – Conditions

APPENDIX C – Analysis of Merger Simulation Models

APPENDIX D – Analysis of AT&T’s FWLL Coverage and Performance Claims and Claimed Rural

Benefits

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1. In this proceeding, we approve, subject to conditions, the applications of AT&T Inc.

(“AT&T”) and DIRECTV (collectively, the “Applicants”) for Commission consent to the transfer of

control of various Commission licenses and other authorizations from DIRECTV to AT&T pursuant to

Section 310(d) of the Communications Act of 1934, as amended (the “Act”).

1

2. Our consent to transfer these licenses is based on a careful review of the economic,

documentary, and other record evidence. We engaged in a rigorous analysis of the potential harms and

benefits to ensure that the proposed transaction serves the public interest, convenience, and necessity.

2

Based on this review, we have concluded that, with the adoption of certain conditions designed to address

specific harms and confirm certain benefits that would result from the transaction, the license transfer is

in the public interest.

3. Our record supports the Applicants’ claim that the newly combined entity will be a more

effective multichannel video programming distributor (“MVPD”) competitor, offering consumers greater

choice at lower prices. As standalone companies, neither has the full set of assets necessary to compete

against the dominant providers of video service. Although DIRECTV has approximately 20 million

video subscribers, it lacks broadband

3

capabilities. This limits DIRECTV in its ability to offer video-on-

demand (“VOD”) and other interactive viewing experiences that consumers increasingly seek. In

addition, DIRECTV’s current partnerships with broadband providers to sell third-party bundles of

broadband and DIRECTV satellite video cannot match the convenience and lower prices associated with

bundles of broadband and video offered by a single provider. AT&T offers bundles of its own broadband

and U-verse video where it has deployed fiber to the node (“FTTN”) or fiber to the premises (“FTTP”)

technologies – however, it too faces significant competitive challenges. With fewer than 6 million

subscribers, AT&T’s video product is hampered by higher costs of procuring programming – limiting its

ability to both offer lower consumer prices and expand its high-speed broadband footprint.

4. We find that the combined AT&T-DIRECTV will increase competition for bundles of

video and broadband, which, in turn, will stimulate lower prices, not only for the Applicants’ bundles, but

also for competitors’ bundled products – benefiting consumers and serving the public interest. We also

expect that this improved business model will spur, in the long term, AT&T’s investment in high-speed

broadband networks, driving more competition and thus expanding consumer access and choice. This is,

in other words, a bet on competition.

5. However, the transaction also creates the potential for competitive harms, which we

impose conditions to address.

6. First, the Applicants’ claim that a benefit of this transaction is that it would increase

AT&T’s incentive to deploy FTTP. To the contrary, we find that the transaction creates, at least in the

short term, a disincentive to deploy faster broadband because an FTTP buildout would potentially

“cannibalize” profits from AT&T’s newly acquired DIRECTV subscribers and revenue. To address this

harm, we impose as a condition that the combined entity deploy FTTP to 12.5 million locations within

four years, to capture all of AT&T’s pre-transaction planned deployment, its projected deployment absent

the transaction, and the deployment that the record suggests is profitable as a result of the transaction. In

addition, and because it is important that competition with cable also reach public institutions, AT&T is

required to offer to schools and libraries where it deploys FTTP, which is about 6,000 institutions, the

ability to purchase 1 gigabit E-rate services from AT&T.

1

See 47 U.S.C. § 310(d); Application of AT&T Inc. and DIRECTV, Description of Transaction, Public Interest

Showing, and Related Demonstrations, transmitted by letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to

Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90, at 10 (filed June 11, 2014) (“Application”).

2

47 U.S.C. § 310(d).

3

Unless the context indicates otherwise, this Order uses the term “broadband” colloquially to refer to the Internet

services AT&T provides other than dial-up Internet services.

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

5

7. Second, Applicants have stated that as a result of this transaction they will be able to

offer their own new, flexible, and innovative online video products, which increases the risk that the

combined entity will use its broadband services to hamper competition from online video content or

online video distribution services. We also note that AT&T is alone among the large Internet Service

Providers (“ISPs”) in applying fixed data caps across its broadband services. Thus we impose as a

condition certain restrictions on the use of discriminatory usage-based allowances. We also impose

certain disclosure requirements for interconnection agreements and interconnection metrics, which will

help the Commission address any future concerns about the nature of AT&T’s exchange of Internet traffic

and the potential impact of congestion upon consumers. Coupled with the FTTP buildout requirements,

these conditions improve the ability of alternative video distribution methods to replace the loss of a

horizontal MVPD competitor within AT&T’s video footprint that results from this merger.

8. Third, while we acknowledge that a benefit of the transaction is the Applicants’ ability to

be a more effective competitor to cable providers, we are concerned that the Applicants’ efforts to expand

consumer choice for bundles might prove to be an obstacle for low-income populations who desire

standalone broadband. Thus we impose as a condition a requirement that the Applicants offer discounted

broadband Internet access to eligible consumers.

9. In addition to addressing potential harms and confirming potential benefits, these

conditions as a group create the opportunity for more robust broadband and video distribution

competition in a variety of respects. To ensure that the goals of these conditions are achieved, we require

as a condition of this transaction that the Applicants employ an independent, outside officer responsible

for monitoring and reporting to the Commission any failure to comply with the conditions imposed by

this Order.

10. In general, these conditions will run for four years from the consummation of the

transaction and, with them in place, we find that this combination is in the public interest.

II. DESCRIPTION OF THE APPLICANTS

A. AT&T

11. AT&T provides Internet, video, local and long distance voice, mobile wireless voice and

broadband, and Wi-Fi services in the United States.

4

In addition, AT&T offers worldwide wireless

service and Internet Protocol (“IP”)-based business communications services.

5

Within the United States,

AT&T’s wireline footprint covers portions of 22 states, while its Long Term Evolution (“LTE”) wireless

network covers approximately 300 million people.

6

AT&T offers bundles of high-speed broadband,

video, and Voice over Internet Protocol (“VoIP”) services under its U-verse brand within portions of its

wireline footprint.

7

Through its Project Velocity IP (“Project VIP”), AT&T has stated that it has begun

an expansion of its U-verse services to reach approximately 57 million customer locations or 75 percent

of its wireline footprint.

8

Of these 57 million customer locations, AT&T states that it plans to deploy

FTTN or FTTP technologies to deliver U-verse video, high-speed broadband, and VoIP services to 33

million customer locations.

9

For the remaining 24 million customer locations where U-verse services are

4

See Application at 10.

5

Id.

6

Id.

7

Id.

8

Id. at 10-11.

9

Id. at 10. According to the Application, AT&T currently uses FTTN architecture in most of the U-verse video

footprint. Id. at 11. Under this approach, AT&T deploys fiber to neighborhood nodes. Individual customer

locations are connected to the network via existing copper plant using very-high-bit-rate digital subscriber line

(“VDSL”) technology. Id. U-verse FTTN offers speeds of up to 45 megabits per second (“Mbps”). Id. At the time

(continued….)

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

6

or will be available, AT&T’s IPDSLAM (“IPDSL”) technology will deliver U-verse high-speed

broadband and VoIP services, but not video services.

10

12. AT&T currently provides broadband Internet access service to approximately 14.5

million residential subscribers of which 6.5 million subscribers receive broadband Internet access service

at download speeds above 10 Mbps.

11

AT&T provides MVPD services to approximately 6 million

subscribers.

12

AT&T estimates that more than 97 percent of its U-verse video subscribers purchase at

least one other U-verse product and about two-thirds of U-verse video subscribers bundle three or four

services from AT&T.

13

Post-transaction, IPDSL customers, which currently are not offered U-verse

video service, could purchase DIRECTV satellite video from the combined entity.

B. DIRECTV

13. DIRECTV offers direct-to-home satellite digital television services to consumers

nationwide.

14

According to the Application, DIRECTV is a “pure-play” satellite video provider with

approximately 20 million U.S. subscribers.

15

Currently, DIRECTV does not provide any broadband or

voice services of its own.

16

It does offer synthetic service

17

bundles of DIRECTV satellite video service

and broadband and/or voice services provided by various third-party telecommunications, cable, and

satellite partners, including AT&T.

18

14. DIRECTV owns and operates two regional sports networks (“RSNs”), Root Sports

Pittsburgh and Root Sports Rocky Mountain, and holds a minority interest in, and manages, the Seattle-

based RSN, Root Sports Northwest.

19

In a recent joint venture, DIRECTV and AT&T have also acquired

majority ownership of a Houston-area RSN (“CSN Houston”) out of bankruptcy and relaunched it as

(Continued from previous page)

of the Application, AT&T was using in Austin, Texas, FTTP architecture in which fiber extends all the way to a

customer’s location. Id. AT&T provides “U-verse with GigaPower” service over this FTTP architecture, and it

plans to offer Internet speeds of up to 1 gigabit per second (“Gbps”). Id. Prior to the DIRECTV transaction, AT&T

announced plans to bring its FTTP deployment and U-verse with GigaPower service to Dallas; Raleigh-Durham,

N.C.; and Winston-Salem, N.C.; and to expand further, to as many as 21 other major metropolitan areas, including

Atlanta; Chicago; Charlotte, N.C.; San Francisco; and Houston. Id. at 11-12.

10

Id. at 11. According to the Application, IPDSL provides high-speed broadband over copper wires at speeds up to

18 Mbps, but it is not suitable for delivering U-verse video services. Id. at 12.

11

See AT&T Inc. Updated Response to Sept. 9, 2014, Information and Discovery Requests, transmitted by letter

from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Vanessa Lemmé, Media Bureau, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90,

Exhibit 5.b.1 – updated (Oct. 20, 2014) (“AT&T Updated Response to Sept. 9, 2014, Information Request”).

12

See id.

13

Application at 12. Where AT&T U-verse FTTP, FTTN, or IPDSL are not available within AT&T’s wireline

footprint, AT&T sells legacy digital subscriber line (“DSL”) Internet service, providing speeds of up to 6 Mbps, and

does not sell its own video component. Id. at 12 n.14.

14

Id. at 13.

15

Id. DIRECTV also holds interests in entities with approximately 18 million video subscribers in Latin America.

Id. at 13, 15.

16

Id. at 13-14.

17

A synthetic bundle is a bundle of services offered by two different companies. See infra ¶ 56 (discussing

synthetic bundles).

18

Application at 14. DIRECTV has arm’s length agreements to provide these synthetic bundles with CenturyLink,

AT&T, Verizon, Exede, Cincinnati Bell, HughesNet, Windstream, and Mediacom, among others. Id.

19

Id.

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

7

Root Sports Southwest.

20

DIRECTV also has a 42 percent non-controlling interest in the Game Show

Network, and smaller, minority interests in the MLB Network, the NHL Network, and a handful of other

networks.

21

III. THE PROPOSED TRANSACTION

A. Description

15. AT&T has entered into an agreement with DIRECTV whereby AT&T will acquire

DIRECTV in a stock-and-cash transaction.

22

Under the terms of the agreement, each share of DIRECTV

common stock will be converted into $28.50 in cash plus the right to receive between 1.724 and 1.905

shares of AT&T common stock, depending on AT&T’s stock price prior to closing.

23

At closing,

DIRECTV will merge with and into a wholly owned subsidiary of AT&T, Steam Merger Sub LLC,

which will be the surviving entity and will be renamed “DIRECTV.”

24

The new DIRECTV will own the

stock of the subsidiaries of the pre-transaction DIRECTV, and these subsidiaries will continue to hold the

Commission licenses and other authorizations they held prior to the transaction.

25

B. Application and Review Process

16. On June 11, 2014, AT&T and DIRECTV filed the Application.

26

On August 7, 2014, the

Commission released the Public Notice accepting the Application for filing and establishing a pleading

20

Joint Opposition of AT&T Inc. and DIRECTV to Petitions to Deny and Condition and Reply to Comments,

transmitted by letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB

Docket No. 14-90, at 55 (filed Oct. 16, 2014) (“Joint Opposition”). See also In re Houston Reg’l Sports Network,

LP, 514 B. R. 211 (Bankr. S.D. Tex. 2014) (“In re Houston”).

21

Application at 14.

22

Id. at 16.

23

Id.

24

Id.

25

Id. at 16-17.

26

See supra n.1. Subsequent to filing the Application and prior to release of the Public Notice accepting the

Application for filing, the Applicants submitted additional information. See Letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys,

Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (Aug. 6, 2014) (submitting

merger simulation and supporting data relied upon in the Declaration of Michael L. Katz); Letter from Maureen R.

Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (July 28, 2014)

(submitting paper prepared by Compass Lexecon entitled “Additional Detail on the Demand Estimation, Merger

Simulation, and Investment Model Analysis Performed by Professor Katz” and associated files); Letter from

Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (July 28,

2014) (submitting paper entitled “Overview of AT&T FTTP Investment Model” and associated files); Letter from

Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (July 24,

2014) (submitting copy of presentation made by Professors Berry and Haile); Letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys,

Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (July 21, 2014) (submitting

additional materials supporting the merger simulation described in the presentation prepared by Professors Berry

and Haile); Letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB

Docket No. 14-90 (July 17, 2014) (submitting (1) presentation prepared by Professors Steve Berry and Phil Haile of

Yale University on behalf of the Applicants; and (2) data supporting the merger simulation described in the

presentation); Letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB

Docket No. 14-90 (July 17, 2014) (submitting additional data supporting the merger simulation relied upon in the

Declaration of Michael L. Katz); Letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch,

Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (July 8, 2014) (submitting additional materials relied upon in the Declaration

of Michael L. Katz); Letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC,

MB Docket No. 14-90 (July 7, 2014) (submitting additional details on the number of (1) customer locations and

subscribers for FTTP and FTTN technologies; and (2) consumer and business customer subscribers); Letter from

(continued….)

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

8

cycle.

27

Eight petitions to deny and thousands of public comments and other filings were received in this

proceeding.

28

In addition to building its record through public comment, the Commission requested

additional information from the Applicants

29

and other entities.

30

The responses to those requests are

included in the record,

31

subject to the protections of the Protective Order issued in this proceeding.

32

(Continued from previous page)

Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (June 30,

2014) (submitting additional materials relied upon in the Declaration of Michael L. Katz); Letter from Maureen R.

Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (June 27, 2014)

(describing the (1) number of customer locations that AT&T serves by the following technology, and (2) the number

of subscribers by service to each technology); Letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H.

Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (June 25, 2014) (submitting the FTTP model and supporting data

relied upon in the Declaration of Michael L. Katz); Letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene

H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (June 23, 2014) (submitting additional data supporting the merger

simulation relied upon in the Declaration of Michael L. Katz); Letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T,

to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (June 20, 2014) (submitting additional materials

relied upon in the Declaration of Michael L. Katz); Letter from William M. Wiltshire, Counsel for DIRECTV, to

Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (June 19, 2014) (submitting materials considered by

Michael L. Katz in preparing his Declaration); Letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H.

Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (June 17, 2014) (submitting merger simulation and supporting data

relied upon in the Declaration of Michael L. Katz).

27

See Commission Seeks Comment on Applications of AT&T Inc. and DIRECTV to Transfer Control of FCC

Licenses and Other Authorizations, MB Docket No. 14-90, Public Notice, DA 14-1129, 29 FCC Rcd 9464 (MB

2014) (“Public Notice”). The Public Notice established September 16, 2014, as the deadline for filing comments or

petitions to deny, and October 16, 2014, as the deadline for responses to comments or oppositions to petitions to

deny. See id. On August 28, 2014, the Media Bureau denied a request to extend the filing deadline for initial

comments and petitions to deny. See Applications of AT&T Inc. and DIRECTV to Transfer Control of FCC

Licenses, MB Docket No. 14-90, Order, DA 14-1253, 29 FCC Rcd 10318 (MB 2014). The deadline for filing

replies was extended to January 7, 2015. See Commission Restarts Clock in Comcast-Time Warner Cable and

AT&T-DIRECTV Merger Proceedings and Establishes Dates for Respective Pleading Cycles, MB Docket No. 14-

90, Public Notice, DA 14-1739, 29 FCC Rcd 14491 (MB 2014) (“Notice of Merger Pleading Cycle Restarts”).

28

Petitions to Deny or to Impose Conditions were filed by: Alliance for Community Media, the Alliance for

Communications Democracy, and Common Cause; Cox Communications, Inc.; DISH Network Corporation; The

Greenlining Institute; Free Press; Public Knowledge and Institute for Local Self-Reliance; and Writers Guild of

America, West, Inc.

29

See Letter to Robert W. Quinn, Jr., Senior Vice President – Federal Regulatory and Chief Privacy Officer, AT&T,

from William T. Lake, Chief, Media Bureau, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90, 2014 WL 4460323 (Sept. 9, 2014)

(“Sept. 9, 2014, Information Request to AT&T”); Letter to Stacy Fuller, Vice President, Regulatory Affairs,

DIRECTV, from William T. Lake, Chief, Media Bureau, MB Docket No. 14-90, 2014 WL 4460324 (Sept. 9, 2014)

(“Sept. 9, 2014, Information Request to DIRECTV”). Additional information was also sought from the Applicants

later in the Commission’s review. See Letter to Robert W. Quinn, Jr., Senior Vice President – Federal Regulatory

and Chief Privacy Officer, AT&T, from Jamillia Ferris, Office of the General Counsel, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90,

2014 WL 6070716 (Nov. 14, 2014) (“Nov. 14, 2014, Information Request to AT&T”); Letter to Robert W. Quinn,

Jr., Senior Vice President – Federal Regulatory and Chief Privacy Officer, AT&T, from Jamillia Ferris, Office of the

General Counsel, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90, 2014 WL 7172163 (Dec. 15, 2014) (“Dec. 15, 2014, Information

Request to AT&T”).

30

See Letter to Catherine Bohigian, Executive Vice President – Government Affairs, Charter Communications, Inc.,

from William T. Lake, Chief, Media Bureau, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90, 2015 WL 128688 (Jan. 8, 2015); Letter

to Steven Teplitz, Senior Vice President – Government Relations, Time Warner Cable Inc., from William T. Lake,

Chief, Media Bureau, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90, 2015 WL 128689 (Jan. 8, 2015); Letter to Kathryn Zachem,

Senior Vice President – Regulatory and State Legislative Affairs, Comcast Corporation, from William T. Lake,

Chief, Media Bureau, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90, 2015 WL 223239 (Jan. 8, 2015).

31

See AT&T Inc. Response to Sept. 9, 2014, Information and Discovery Requests, transmitted by letter from

Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Vanessa Lemmé, Media Bureau, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (Oct. 7,

(continued….)

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

9

17. In addition to Commission review, the proposed transaction is subject to review by the

United States Department of Justice (“DOJ”) pursuant to its concurrent authority in Section 7 of the

Clayton Act.

33

IV. STANDARD OF REVIEW AND PUBLIC INTEREST FRAMEWORK

18. Pursuant to Section 310(d) of the Act, we must determine whether the Applicants have

demonstrated that the proposed transfer of control of licenses and authorizations will serve the public

interest, convenience, and necessity.

34

In making this determination, we assess whether the proposed

transaction complies with the specific provisions of the Act,

35

other applicable statutes, and the

(Continued from previous page)

2014) (“AT&T Response to Sept. 9, 2014, Information Request”); AT&T Updated Response to Sept. 9, 2014,

Information Request; DIRECTV Response to Sept. 9, 2014, Information and Discovery Requests, transmitted by

letter from William M. Wiltshire, Counsel for DIRECTV, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No.

14-90 (Oct. 7, 2014) (“DIRECTV Response to Sept. 9, 2014, Information Request”); AT&T Inc. Response to Nov.

14, 2014, Information and Discovery Requests, transmitted by letter Robert W. Quinn, Jr., Senior Vice President –

Federal Regulatory and Chief Privacy Officer, AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90

(Nov. 25, 2014) (“AT&T Response to Nov. 14, 2014, Information Request”); AT&T Inc. Response to Sept. 9, 2014,

and Dec. 15, 2014, Information and Discovery Requests, transmitted by letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel

for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (Dec. 19, 2014) (“AT&T Response to

Dec. 15, 2014, Information Request”); Comcast Corporation Response to Jan. 8, 2015, Information and Data

Request, transmitted by letter from Kathyrn A. Zachem, Senior Vice President – Regulatory and State Legislative

Affairs, Comcast Corporation, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (Jan. 23, 2015)

(“Comcast Response to Jan. 8, 2015, Information Request”); Time Warner Cable Inc. Response to Jan. 8, 2015,

Information and Data Request, transmitted by letter from Matthew A. Brill, Counsel for Time Warner Cable, to

Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (Jan. 23, 2015) (“Time Warner Cable Response to Jan.

8, 2015, Information Request”); Charter Communications, Inc. Response to Jan. 8, 2015, Information and Data

Request, transmitted by letter from John L. Flynn, Counsel for Charter, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB

Docket No. 14-90 (Jan. 20, 2015) (“Charter Response to Jan. 8, 2015, Information Request”).

32

The Media Bureau adopted a Protective Order to (i) limit access to proprietary or confidential information filed in

this proceeding and (ii) more strictly limit access to certain particularly competitively sensitive information. See

Applications of AT&T Inc. and DIRECTV to Transfer Control of FCC Licenses, MB Docket No. 14-90, Joint

Protective Order, DA 14-804, 29 FCC Rcd 6047 (MB 2014), modified by DA 14-1465, 29 FCC Rcd 11883 (MB

2014), amended by DA 14-1602, 29 FCC Rcd 13616 (MB 2014), amended by DA 14-1640, 29 FCC Rcd 13810

(MB 2014) (“Protective Order”). In this Order, Highly Confidential Information, as defined in the Protective

Order, will be marked by the terms “[BEGIN HIGHLY CONF. INFO.]” and “[END HIGHLY CONF. INFO.],”

or “[BEGIN VIDEO PROG. CONF. INFO.]” and “[END VIDEO PROG. CONF. INFO.]” as appropriate. In

this Order, Confidential Information, as defined in the Protective Order, will be marked by the terms “[BEGIN

CONF. INFO.]” and “[END CONF. INFO.]” as appropriate. Such information will be redacted from the publicly

available version of the Order. The unredacted information will be available upon request to persons qualified to

view it under the Protective Order.

33

15 U.S.C. § 18.

34

47 U.S.C. § 310(d); 47 C.F.R. § 25.119.

35

Section 310(d) requires that we consider applications as if the proposed transferee were applying for the licenses

directly. 47 U.S.C. § 310(d). See Applications of Comcast Corporation, General Electric Company, and NBC

Universal, Inc. for Consent to Assign Licenses and Transfer Control of Licensees, MB Docket No. 10-56,

Memorandum Opinion and Order, 26 FCC Rcd 4238, 4247, ¶ 22 n.42 (2011) (“Comcast-NBCU Order”);

Applications for Consent to the Transfer of Control of Licenses, XM Satellite Radio Holdings Inc., Transferor, to

Sirius Satellite Radio Inc., Transferee, MB Docket No. 07-57, Memorandum Opinion and Order and Report and

Order, 23 FCC Rcd 12348, 12363, ¶ 30 n.114 (2008) (“Sirius-XM Order”); News Corp. and DIRECTV Group, Inc.

and Liberty Media Corp. for Authority to Transfer Control, Memorandum Opinion and Order, MB Docket No. 07-

18, 23 FCC Rcd 3265, 3276, ¶ 22 n.72 (2008) (“Liberty Media-DIRECTV Order”); Application of EchoStar

Communications Corporation, General Motors Corporation, and Hughes Electronics Corporation (Transferors)

(continued….)

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

10

Commission’s rules.

36

If the transaction does not violate a statute or rule, we consider whether the

transaction could result in public interest harms by substantially frustrating or impairing the objectives or

implementation of the Act or related statutes.

37

We then employ a balancing test weighing any potential

public interest harms of the proposed transaction against any potential public interest benefits.

38

The

Applicants bear the burden of proving, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the proposed transaction,

on balance, serves the public interest.

39

If we are unable to find that the proposed transaction serves the

public interest for any reason, or if the record presents a substantial and material question of fact, we must

designate the Application for hearing.

40

19. Our public interest evaluation necessarily encompasses the “broad aims of the

Communications Act,” which include, among other things, a deeply rooted preference for preserving and

enhancing competition, accelerating private sector deployment of advanced services, promoting a

diversity of information sources and services to the public, and generally managing the spectrum in the

public interest.

41

Our public interest analysis also entails assessing whether the proposed transaction

would affect the quality of communications services or result in the provision of new or additional

services to consumers.

42

In conducting this analysis, we may consider technological and market changes,

and the nature, complexity, and speed of change of, as well as trends within, the communications

industry.

43

20. Our competitive analysis, which forms an important part of the public interest evaluation,

is informed by, but not limited to, traditional antitrust principles.

44

The Commission and the DOJ each

has independent authority to examine the competitive impacts of proposed communications mergers and

transactions involving transfers of Commission licenses, but the standards governing the Commission’s

competitive review differ somewhat from those applied by the DOJ.

45

The Commission, like the DOJ,

considers how a transaction would affect competition by defining a relevant market, looking at the market

(Continued from previous page)

and EchoStar Communications Corporation (Transferee), MB Docket No. 01-348, Hearing Designation Order, 17

FCC Rcd 20559, 20574, ¶ 25 n.102 (2002) (“EchoStar-DIRECTV HDO”).

36

See Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4247, ¶ 22; Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 12363-64, ¶ 30; Liberty

Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3276-77, ¶ 22; EchoStar-DIRECTV HDO, 17 FCC Rcd at 20574, ¶ 25.

37

See id.

38

See id.; General Motors Corp. and Hughes Electronics Corp., Transferors, and the News Corporation,

Transferee, MB Docket No. 03-124, Memorandum Opinion and Order, 19 FCC Rcd 473, 483, ¶ 15 (2004) (“News

Corp.-Hughes Order”).

39

See id.

40

See 47 U.S.C. § 309(e); see also Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4247-48, ¶ 22; Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC

Rcd at 12364, ¶ 30; Liberty Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3277, ¶ 22; News Corp.-Hughes Order, 19 FCC

Rcd at 483, ¶ 15 n.49; EchoStar-DIRECTV HDO, 17 FCC Rcd at 20574, ¶ 25.

41

See Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4248, ¶ 23; Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 12364, ¶ 31; Liberty

Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3277-78, ¶ 23; News Corp.-Hughes Order, 19 FCC Rcd at 483-84, ¶ 16;

EchoStar-DIRECTV HDO, 17 FCC Rcd at 20575, ¶ 26.

42

See Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4248, ¶ 23; Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 12365, ¶ 31; Liberty

Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3277-78, ¶ 23; EchoStar-DIRECTV HDO, 17 FCC Rcd at 20575, ¶ 26.

43

See id.

44

See Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4248, ¶ 24; Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 12365, ¶ 32; Liberty

Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3278, ¶ 24; News Corp.-Hughes Order, 19 FCC Rcd at 484, ¶ 17;

EchoStar-DIRECTV HDO, 17 FCC Rcd at 20575, ¶ 27.

45

See, e.g., id.

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

11

power of incumbent competitors, and analyzing barriers to entry, potential competition, and the

efficiencies, if any, that may result from the transaction.

46

21. The DOJ, however, reviews telecommunications mergers pursuant to Section 7 of the

Clayton Act, and if it sues to enjoin a merger, it must demonstrate to a court that the merger may

substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.

47

The DOJ review is consequently limited

solely to an examination of the competitive effects of the acquisition, without reference to diversity,

localism, or other public interest considerations.

48

Moreover, the Commission’s competitive analysis

under the public interest standard is broader. For example, the Commission considers whether a

transaction would enhance, rather than merely preserve, existing competition, and often takes a more

expansive view of potential and future competition in analyzing that issue.

49

22. Finally, our public interest authority enables us, where appropriate, to impose and enforce

transaction-related conditions that ensure that the public interest is served by the transaction.

50

Specifically, Section 303(r) of the Communications Act authorizes the Commission to prescribe

restrictions or conditions not inconsistent with law that may be necessary to carry out the provisions of

the Act.

51

Indeed, our extensive regulatory and enforcement experience enables us, under this public

interest authority, to impose and enforce conditions to ensure that the transaction will yield overall public

interest benefits.

52

In exercising this authority to carry out our responsibilities under the Act and related

statutes, we have imposed conditions to confirm specific benefits or remedy specific harms likely to arise

from transactions.

53

46

See Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 12365, ¶ 32; see also Applications of Sprint Nextel Corp. and SoftBank

Corp. and Starburst II, Inc. for Consent to Transfer Control of Licenses and Authorizations, IB Docket No. 12-343,

Memorandum Opinion and Order, Declaratory Ruling, and Order on Reconsideration, 28 FCC Rcd 9642, 9652, ¶ 25

(2013) (“SoftBank-Sprint Order”).

47

15 U.S.C. § 18; see also Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4248, ¶ 24; Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC Rcd at

12365, ¶ 32; Liberty Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3278, ¶ 24; News Corp.-Hughes Order, 19 FCC Rcd at

484, ¶ 17; EchoStar-DIRECTV HDO, 17 FCC Rcd at 20575, ¶ 27.

48

See SoftBank-Sprint Order, 28 FCC Rcd at 9652, ¶ 25; Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 12365, ¶ 32; Liberty

Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3278, ¶ 24.

49

See Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4248, ¶ 24; Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 12365-66, ¶ 32; see also

Liberty Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3278-79, ¶ 25; EchoStar-DIRECTV HDO, 17 FCC Rcd at 20575, ¶

27.

50

See Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4249, ¶ 25; Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 12366, ¶ 33; Liberty

Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3279, ¶ 26; see also Application of WorldCom, Inc. and MCI

Communications Corporation for Transfer of Control of MCI Communications Corporation to WorldCom, Inc., CC

Docket No. 97-211, Memorandum Opinion and Order, 13 FCC Rcd 18025, 18032, ¶ 10 (1998) (“WorldCom-MCI

Order”) (stating that the Commission may attach conditions to the transfers).

51

47 U.S.C. § 303(r). See Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4249, ¶ 25; Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC Rcd at

12366, ¶ 33; Liberty Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3279, ¶ 26; WorldCom-MCI Order, 13 FCC Rcd at

18032, ¶ 10 (citing FCC v. Nat’l Citizens Comm. for Broad., 436 U.S. 775 (1978) (upholding broadcast-newspaper

cross-ownership rules adopted pursuant to Section 303(r))); United States v. Southwestern Cable Co., 392 U.S. 157,

178 (1968) (holding that Section 303(r) permits the Commission to order a cable company not to carry broadcast

signal beyond station’s primary market); United Video, Inc. v. FCC, 890 F.2d 1173, 1182-83 (D.C. Cir. 1989)

(affirming syndicated exclusivity rules adopted pursuant to Section 303(r) authority).

52

See Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4249, ¶ 25; Sirius-XM Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 12366, ¶ 33; Liberty

Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3279, ¶ 26.

53

See Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4249, ¶ 25; Liberty Media-DIRECTV Order, 23 FCC Rcd at 3279,

¶ 26.

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

12

23. This Order examines the proposed transaction as follows. First, we examine whether the

transaction complies with the Act, other applicable statutes, and the Commission’s rules and policies, and

we assess the qualifications of the Applicants. Second, we consider the potential harms and purported

public interest benefits resulting from the transaction. Then, we consider and, where appropriate, impose

conditions to ameliorate the harms or confirm the benefits. Finally, we balance the public interest harms

posed by and the benefits to be gained from the transaction.

V. QUALIFICATIONS OF APPLICANTS

A. Background

24. Section 310(d) of the Act requires that we make a determination as to whether the

Applicants have the requisite qualifications to hold Commission licenses.

54

Among the factors the

Commission considers in its public interest review is whether the applicant for a license has the requisite

“citizenship, character, and financial, technical, and other qualifications.”

55

As a threshold matter, the

Commission must determine whether the Applicants to the proposed transaction – both the transferee and

the transferor – meet the requisite qualifications and requirements to hold and transfer licenses under

Section 310(d) and the Commission’s rules.

56

With respect to Commission-related conduct, the

Commission has stated that all violations of the Act, or of the Commission’s rules or policies, are

predictive of an applicant’s future truthfulness and reliability and thus have a bearing on an applicant’s

character qualifications.

57

The Commission has previously determined that in its review of character

issues, it will also consider certain types of adjudicated, non-Commission-related misconduct,

specifically: (1) felony convictions; (2) fraudulent misrepresentation to governmental units; and (3)

violations of antitrust or other laws protecting competition.

58

For the reasons discussed below, we find

that the Applicants have the requisite character qualifications to hold Commission licenses.

B. DIRECTV

25. No parties have raised issues with respect to the basic qualifications of the transferor,

DIRECTV. The Commission generally does not reevaluate the qualifications of transferors unless issues

related to basic qualifications have been sufficiently raised in petitions to warrant designation for

hearing.

59

We find that there is no reason to reevaluate the requisite citizenship, character, financial,

technical, or other basic qualifications under the Communications Act and our rules, regulations, and

policies, of DIRECTV.

54

47 U.S.C. § 310(d).

55

47 U.S.C. §§ 308, 310(d); see Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4349, ¶ 276; News Corp.-Hughes Order, 19

FCC Rcd at 485, ¶ 18; EchoStar-DIRECTV HDO, 17 FCC Rcd at 20576, ¶ 28.

56

See 47 U.S.C. § 310(d); see also, e.g., Comcast-NBCU Order, 26 FCC Rcd at 4349, ¶ 276; News Corp.-Hughes

Order, 19 FCC Rcd at 485, ¶ 18; EchoStar-DIRECTV HDO, 17 FCC Rcd at 20576, ¶ 28.

57

See Applications of Cellco Partnership d/b/a Verizon Wireless and Atlantis Holdings LLC for Consent to Transfer

Control of Licenses, Authorizations, and Spectrum Manager and de facto Transfer Leasing Arrangements, WT

Docket No. 08-95, Memorandum Opinion and Order and Declaratory Ruling, 23 FCC Rcd 17444, 17464, ¶ 32

(2008) (citations omitted) (“Verizon Wireless-ALLTEL Order”).

58

See Applications of AT&T Wireless Services, Inc. and Cingular Wireless Corporation for Consent To Transfer

Control of Licenses and Authorizations, Memorandum Opinion and Order, 19 FCC Rcd 21522, 21548, ¶ 47 (2004)

(“AT&T-Cingular Order”).

59

See, e.g., SoftBank-Sprint Order, 28 FCC Rcd at 9653, ¶ 27.

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

13

C. AT&T

26. Two parties, Minority Cellular Partners Coalition (“MCPC”) and New Networks Institute

& Teletruth (“New Networks”), have raised issues with respect to the basic qualifications of the

transferee, AT&T.

60

These issues are discussed more fully below.

1. Minority Cellular Partners Coalition Comments

27. The Commission has determined on numerous occasions that AT&T was qualified to

acquire Commission licenses.

61

Here, MCPC

62

questions those qualifications. MCPC first alleges that

AT&T defrauded its minority partners and engaged in serious Commission-related misconduct, including

forcing out minority partners in certain cellular license partnerships, and that AT&T engaged in related

violations of the Commission’s license transfer rules.

63

It states that the Commission, through an

evidentiary hearing or otherwise, should elicit the facts necessary to resolve the question of whether

AT&T intentionally violated Section 310(d) of the Act and Sections 1.17 and 1.948 of the Rules.

64

In

60

On May 4, 2015, Erik Underwood, Founder and CEO of My24HourNews.Com, Inc., belatedly informed the

Commission that he opposes the transaction and requested that the Commission suspend its review until the

completion of civil litigation recently initiated by My24HourNews.Com concerning a contract dispute between

My24HourNews.Com and AT&T. Letter from Erik M. Underwood, Founder/CEO My24HourNews.Com, Inc., to

Thomas Wheeler, Chairman, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90 (May 4, 2015) (“Underwood Letter”); see also Email

from Erik M. Underwood to Thomas Wheeler, MB Docket No. 14-90 (June 11, 2015) (attaching Complaint and

Civil Cover Sheet in My24HourNews.Com, Inc. v. AT&T Corp., No. 1:15-cv-01210 (D. Colo. filed June 9, 2015)).

Although Underwood asserts that “AT&T has violated anti-competition and telecommunication laws of this

country,” Underwood Letter at 1, he does not identify any specific Commission rule or policy or any provision of

the Communications Act that he believes is at issue. Underwood also claims that he attached confidential emails to

his letter as evidence of AT&T’s anticompetitive conduct. We have been unable to ascertain that we received the

emails and note that Underwood did not file them according to the procedures specified for the filing of confidential

information. See Protective Order, 29 FCC Rcd at 13816, ¶ 14. The pending litigation at issue concerns claims for

breach of contract, misappropriation of intellectual property, and other alleged wrongdoing arising from a pre-

existing dispute not involving the Commission’s rules or the Communications Act. Underwood does not claim that

his request to suspend Commission review of the Application is necessary to address a transaction-specific harm or

benefit or that AT&T lacks the necessary character qualifications to hold Commission licenses. Moreover, except in

limited circumstances that do not apply here, the Commission does not consider unadjudicated claims of non-

Commission misconduct. Policy Regarding Character Qualifications in Broadcast Licensing Amendment of Rules

of Broadcast Practice and Procedure Relating to Written Responses to Commission Inquiries and the Making of

Misrepresentations to the Commission by Permittees & Licensees, Gen. Docket No. 81-500, Report, Order and

Policy Statement, 102 FCC 2d 1179, 1204-06, ¶ 48 (1986), recon. granted in part, denied in part, 1 FCC Rcd 421

(1986), appeal dismissed sub nom. Nat’l Ass’n for Better Broad. v. FCC, No. 86–1179 (D.C. Cir. June 11, 1987)

(“1986 Character Policy Statement”). Thus, we deny the request.

61

See, e.g., Applications of AT&T Mobility Spectrum LLC, New Cingular Wireless PCS, LLC, Comcast

Corporation, Horizon Wi-Com, LLC, NextWave Wireless, Inc., and San Diego Gas & Electric Company for Consent

to Assign and Transfer Licenses, WT Docket No. 12-240, Memorandum Opinion and Order, 27 FCC Rcd 16459,

16466-67, ¶ 19 (2012) (“AT&T-WCS Order”); see also Applications of Cricket License Company, LLC, Leap

Wireless International, Inc., and AT&T Inc. for Consent to Transfer Control and Assignment of Authorizations, WT

Docket No. 13-193, Memorandum Opinion and Order, DA 14-349, 29 FCC Rcd 2735, 2745, ¶ 19 (WTB, IB 2014)

(“AT&T-Leap Wireless Order”); AT&T Inc., Cellco Partnership d/b/a Verizon Wireless, Grain Spectrum, LLC, and

Grain Spectrum II, LLC, WT Docket No. 13-56, Memorandum Opinion and Order, 28 FCC Rcd 12878, 12885, ¶ 17

(2013).

62

MCPC explains that its members were minority partners in partnerships with AT&T that held 11 cellular licenses.

Comments of Minority Cellular Partners Coalition, MB Docket 14-90, at 1 (filed Sept. 16, 2014) (“MCPC

Comments”).

63

See id. at 9-12, 15-17.

64

See id. at 21.

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

14

particular, MCPC maintains that AT&T divested MCPC’s members of their interests in cellular licenses

held in partnership with AT&T by mischaracterizing certain transactions as pro forma license

assignments that require only notification to the Commission, rather than transfers of control that require

prior Commission approval.

65

MCPC notes that, while the Commission’s findings may or may not be

disqualifying, they may work to ensure AT&T’s future compliance with Section 310(d) and be of

substantial aid to the Chancery Court in Delaware, where MCPC’s claims are currently being litigated.

66

28. The Applicants respond that the claims raised by MCPC relate to matters of Delaware

Corporate and Partnership Law that are unrelated to the current proceeding.

67

They note that MCPC’s

claims are already being heard in Delaware Chancery Court, which is the appropriate forum.

68

Further,

they state that MCPC should have raised the allegations about transfer of control years ago.

69

Finally,

AT&T contends it properly filed the pro forma notifications challenged by MCPC in full compliance with

the requirements of Section 310(d).

70

29. MCPC also notes that the Commission issued a notice of apparent liability (“NAL”) in

January 2015, finding that AT&T appeared to have operated a number of wireless stations at variance

with their licensed parameters.

71

While MCPC observes that the unadjudicated NAL it cites cannot be

used against AT&T in this proceeding,

72

it recommends that the Commission examine the facts

underlying the NAL to determine whether AT&T is engaging in a pattern of noncompliant behavior.

73

AT&T responds that the Commission has not yet determined what sanction, if any, is appropriate in that

enforcement proceeding.

74

AT&T argues further that the Commission has concluded in the 1986

Character Policy Statement that an unadjudicated NAL is an inappropriate ground for a finding of

unfitness.

75

30. Finally, MCPC claims that AT&T violated the Communications Assistance for Law

Enforcement Act (“CALEA”)

76

and the Commission’s CALEA rules

77

by participating in the President’s

65

Id. at 15-17.

66

Id. at 21.

67

See Joint Opposition at 73.

68

See id.

69

See id. at 74.

70

See id. at 74-75.

71

Letter from Russell D. Lukas, Counsel for MCPC, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90,

at 1-2 (March 4, 2015) (“MCPC March 4, 2015, Ex Parte Letter”) (citing AT&T Inc., Parent Company of New

Cingular Wireless PCS, LLC and AT&T Mobility Puerto Rico, Inc., Notice of Apparent Liability for Forfeiture, 30

FCC Rcd 856 (2015) (“AT&T Mobility Puerto Rico NAL”)).

72

MCPC March 4, 2015, Ex Parte Letter at 2 (citing 47 U.S.C. § 504(c)).

73

Id. (citing The Commission’s Forfeiture Policy Statement and Amendment of Section 1.80 of the Rules to

Incorporate the Forfeiture Guidelines, CI Docket No. 95-6, Memorandum Opinion and Order, 15 FCC Rcd 303,

304, ¶¶ 3-4 (1999) (“1999 Forfeiture Guidelines”); Infinity Radio Operations, Inc., Order on Review, 22 FCC Rcd

9824, 9827, ¶ 9 (2007) (“Infinity Forfeiture Review Order”).

74

Letter from Maureen R. Jeffreys, Counsel for AT&T, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary, FCC, MB Docket No. 14-

90, at 4-5 (March 11, 2015) (“AT&T March 11, 2015, Ex Parte Letter”).

75

Id. at 5 (citing 1986 Character Policy Statement, 102 FCC 2d at 1204-06, ¶ 48).

76

Section 103(a)(1) of CALEA, 47 U.S.C. § 1002(a)(1), requires telecommunications carriers to establish the

capability of providing to law enforcement agencies (“LEAs”) call content information, pursuant to a court order or

other lawful authorization. Section 103(a)(2) of CALEA, 47 U.S.C. § 1002(a)(2), requires telecommunications

carriers to establish the capability of providing to LEAs reasonably available call-identifying information (“CII”),

pursuant to a court order or other lawful authorization. Section 105 of CALEA, 47 U.S.C. § 1004, requires

(continued….)

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

15

Surveillance Program (“PSP”).

78

According to MCPC, under this program, AT&T permitted the National

Security Agency (“NSA”) to intercept communications or to have access to call-identifying information

without the lawful authorization required by CALEA and the CALEA rules for the 33-month period

ending on July 15, 2004.

79

While MCPC recognizes that AT&T has been granted immunity from civil

damages claims arising from its participation, if any, in the PSP,

80

and that the statute of limitations for

any forfeiture penalty under Section 503(b)(6)(B) of the Communications Act has passed,

81

MCPC

nevertheless advocates that the Commission investigate this matter in the context of this transaction

proceeding for purposes of evaluating AT&T’s qualifications to hold the licenses currently held by

DIRECTV.

82

MCPC also argues that an investigation into AT&T’s involvement with the PSP is

warranted because such an investigation would help restore the public’s confidence in the privacy of their

communications.

83

In addition, MCPC recommends conditioning this transaction on AT&T submitting

its systems security and integrity (“SSI”) plan to the Commission, subject to notice and comment.

84

MCPC asserts that the public’s confidence in the privacy of individuals’ communications has been

“shaken” by AT&T’s participation in the PSP and that a “modicum” of that confidence could be restored

if the Commission were to impose the condition MCPC recommends.

85

a. Standing

31. As an initial matter, although MCPC frames its comments as raising the question of

whether AT&T has the requisite character qualifications to hold Commission licenses, MCPC’s

participation in this proceeding appears to be motivated by its ongoing business dispute with AT&T,

which is wholly unrelated to the transaction. To establish party-in-interest standing to challenge an

application, a petitioner must allege facts sufficient to demonstrate that grant of the application would

(Continued from previous page)

telecommunications carriers to ensure that “any interception of communications or access to call-identifying

information effected within its switching premises can be activated only in accordance with a court order or other

lawful authorization.”

77

See 47 C.F.R. §§ 1.20000-08 (“CALEA rules”).

78

MCPC March 4, 2015, Ex Parte Letter at 5.

79

Id. at 8-11. For background on the PSP, see In re NSA Telecomm. Records Litig., 633 F. Supp. 2d 949, 955-957

(N.D. Cal. 2009).

80

MCPC March 4, 2015, Ex Parte Letter at 11. See also 50 U.S.C. § 1885a (statutory provision in which Congress

granted telecommunications carriers immunity from civil suits to the extent they participated in the PSP under

certain circumstances); In re NSA Telecomm. Records Litig., 671 F.3d 881 (9th Cir. 2011) (finding this grant of

immunity to be Constitutional).

81

MCPC March 4, 2015, Ex Parte Letter at 11 (citing 47 U.S.C. § 503(b)(6)(B)).

82

Id. In response, AT&T points out that substantially similar allegations were raised in a 2006 transfer of control

proceeding. AT&T notes that the Commission did not investigate these issues in the context of the 2006

proceeding, finding that these issues were outside the scope of its investigative powers. AT&T argues that the

Commission should follow that precedent here. AT&T March 11, 2015, Ex Parte Letter at 2-4 (citing AT&T Inc.

and BellSouth Corporation, Application for Transfer of Control, WC Docket No. 06-74, Memorandum Opinion and

Order, 22 FCC Rcd 5662, 5757, ¶ 192 (2007) (“AT&T-BellSouth Merger Order”)). MCPC responded that the

factors underlying the Commission’s decision in the AT&T-BellSouth Merger Order not to investigate these issues

do not apply in this proceeding. Letter from Russell D. Lukas, Counsel for MCPC, to Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary,

FCC, MB Docket No. 14-90, at 1 (March 19, 2015) (“MCPC March 19, 2015, Ex Parte Letter”). We need not

address this issue here because we find for other reasons that this issue does not warrant investigation in this

transaction review proceeding.

83

MCPC March 19, 2015, Ex Parte Letter at 2.

84

MCPC March 4, 2015, Ex Parte Letter at 12; MCPC March 19, 2015, Ex Parte Letter at 2.

85

MCPC March 19, 2015, Ex Parte Letter at 2.

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

16

cause it to suffer a direct injury.

86

In addition, petitioners must demonstrate a causal link between the

claimed injury and the challenged action.

87

To demonstrate a causal link, petitioners must establish that

the injury can be traced to the challenged action and that the injury would be prevented or redressed by

the relief requested.

88

MCPC has not articulated any theory by which the Commission’s disposition of

the Application would redress an injury to MCPC. Moreover, MCPC does not allege that its members are

competitors or viewers of AT&T’s or DIRECTV’s programming.

89

In other words, MCPC does not

allege that its members currently compete with AT&T in the video programming or video distribution

market, or indeed, in any market. Accordingly, we conclude that MCPC’s dispute with AT&T does not

give it standing to object to the transfer of control of DIRECTV to AT&T.

90

b. Pro Forma Transactions

32. At the outset, we note that MCPC’s allegations regarding violations under Delaware law

are being adjudicated by the Chancery Court in Delaware.

91

They do not involve alleged violations of the

Communications Act or Commission rules, and there has been no adjudicated finding of wrongdoing.

Thus, they are outside the scope of our character qualifications inquiry.

92

33. Furthermore, we note that MCPC has not offered any evidence to support its allegations.

Section 309(d)(1) of the Communications Act requires parties filing petitions to deny applications to

support their allegations of fact with an affidavit of a person or persons with personal knowledge

86

See, e.g., AT&T-WCS Order, 27 FCC Rcd at 16465, ¶ 16; Touchtel Corporation, Assignor, Penryn Corporation,

Assignee, Order on Reconsideration, 29 FCC Rcd 16249, 16250-51, ¶ 7 (2014) (“Touchtel Order”). See also AT&T-

Cingular Order, 19 FCC Rcd at 21547, ¶ 46 n.196 (the Commission had “doubts” regarding petitioner’s standing

when there was no demonstration that it would be directly affected by the order); Applications of Nextel

Communications, Inc. and Sprint Corporation For Consent to Transfer Control of Licenses and Authorizations, WT

Docket No. 05-63, Memorandum Opinion and Order, 20 FCC Rcd 13967, 14021, ¶ 150 n.335 (2005) (“Sprint-

Nextel Order”) (same).

87

See Touchtel Order, 29 FCC Rcd at 16250-51, ¶ 7 (and sources cited therein).

88

See id. (and sources cited therein).

89

Sunburst Media-Louisiana, LLC, Memorandum Opinion and Order, 29 FCC Rcd 9777, 9778, ¶ 5 (2014)

(Generally, to establish standing in the broadcast regulatory context, a petitioner must show that it is: (1) a

competitor in the market suffering signal interference; (2) a competitor in the market suffering economic harm; or

(3) a resident of the station’s service area or a regular listener of the station.).

90

We recognize that an informal objection may be filed pursuant to Section 1.41 of the Commission’s rules without

demonstrating standing. 47 C.F.R. § 1.41. The Commission has discretion whether to consider an informal

objection. AT&T-Cingular Order, 19 FCC Rcd at 21547, ¶ 46 n.196; Sprint-Nextel Order, 20 FCC Rcd at 14021, ¶

150 n.335; Touchtel Order, 29 FCC Rcd at 16251, ¶ 8. In this case, we find that the public interest warrants

considering MCPC’s contentions as informal objections. However, for the reasons discussed below, we conclude

that they do not present a substantial and material question of fact warranting further inquiry into AT&T’s character

qualifications. For these reasons, we also find that MCPC’s proposed condition is unnecessary.

91

The matters being considered in the Chancery Court in Delaware address private contractual disputes, for which

the Commission had repeatedly stated it is not the appropriate forum for resolution. See, e.g., AT&T-Cingular

Order, 19 FCC Rcd at 21551, ¶ 56 n.222 (rejecting argument that transfer should be denied on grounds that it

violated partnership agreements; “these are private contractual disputes that are not relevant to our public interest

analysis and are best resolved in courts of competent jurisdiction”).

92

1986 Character Policy Statement, 102 FCC 2d at 1204-06, ¶ 48 (1986); Policy Regarding Character

Qualifications in Broadcast Licensing, Amendment of Part 1, the Rules of Practice and Procedure, Relating to

Written Responses to Commission Inquiries and the Making of Misrepresentations to the Commission by Applicants,

Permittees and Licensees, and the Reporting of Information Regarding Character Qualifications, Memorandum

Opinion and Order, 7 FCC Rcd 6564, 6566, ¶ 9 (1992) (pending litigation involving alleged non-Commission

misconduct is presumptively not relevant to a licensee’s character qualifications).

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-94

17

thereof.

93

MCPC did not submit any such affidavit. Accordingly, even if MCPC did have standing to

raise its allegations, MCPC has not satisfied the evidentiary threshold of Section 309(d)(1) to show that

grant of the Application would be prima facie inconsistent with the public interest so as to warrant further

inquiry.

34. As a separate and independent basis for rejecting MCPC’s allegations, we find that the

allegations are unpersuasive. MCPC claims that AT&T mischaracterized and possibly misrepresented

substantive transfer of control transactions as pro forma transactions that do not require prior Commission

approval, thereby violating a Commission rule.

94

Specifically, as mentioned above, MCPC maintains that

the 11 transactions at issue divested MCPC’s members of their interests in cellular licenses held in

partnership with AT&T and that AT&T mischaracterized those transactions as pro forma.

95

In addition,

MCPC observes that, in 1998, the Commission adopted the Section 310(d) Forbearance Order,

identifying six kinds of transactions as warranting pro forma treatment, and contends that the 11

transactions at issue here do not fit into any of those six categories.

96

35. MCPC is mistaken in asserting that the 11 transactions it cites were not pro forma

transactions. The first type of transaction identified in the Section 310(d) Forbearance Order as

warranting pro forma treatment is an “assignment from an individual or individuals (including

partnerships) to a corporation owned or controlled by such individuals or partnerships without any

substantial change in their relative interests.”

97

In each of the 11 transactions at issue here, AT&T

assigned a license from a partnership to a corporation. These transactions did not result in any substantial

change in ownership because AT&T had de jure and de facto control of each assigning partnership prior

to the assignment and it held such control after the assignment.

98

Therefore, the 11 transactions fit

perfectly within the first category of pro forma transactions identified in the Section 310(d) Forbearance

Order.

99

93

47 U.S.C. § 309(d)(1).

94

MCPC Comments at 16. See also 47 C.F.R. § 1.948(c)(1) (exempting pro forma transactions from the

requirement that licensees obtain approval from the Commission prior to transferring or assigning their licenses).

95

MCPC Comments at 15-17.

96

Id. at 15-16 (citing FCBA’s Petition for Forbearance from Section 310(d) of the Communications Act,

Memorandum Opinion and Order, 13 FCC Rcd 6293 (1998) (“Section 310(d) Forbearance Order”)). In that order,

the Commission decided to forbear from enforcing the requirement in Section 310(d) of the Communications Act

that parties obtain prior approval for transfers of licenses, provided that the license was issued by the Wireless

Telecommunications Bureau, the licensee notified the Bureau prior to completing the transaction, and the

transaction fell into one of the six categories listed in that order. Section 310(d) Forbearance Order, 13 FCC Rcd at

6299, ¶ 9.

97

Section 310(d) Forbearance Order, 13 FCC Rcd at 6298-99, ¶ 8 (quoted in MCPC Comments at 15).

98

See Joint Opposition at 74. See also Section 310(d) Forbearance Order, 13 FCC Rcd at 6297, ¶ 7 (noting that a

pro forma transaction is one in which there is no substantial change in de jure or de facto control).

99

In its reply, MCPC also states that, “[b]y the time the public was notified of AT&T’s actions, the issue of AT&T’s