Gambling in the Golden State

1998 Forward

By Charlene Wear Simmons, Ph.D.

Assistant Director

ISBN 1-58703-210-4

California State Library, California Research Bureau i

Table of Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..............................................................................................

1

A F

AST GROWING AND PROFITABLE INDUSTRY........................................................... 1

STATE REGULATION....................................................................................................... 2

ECONOMIC BENEFITS AND SOCIAL COSTS.................................................................... 2

Problem and Pathological Gambling........................................................................ 3

Crime .......................................................................................................................... 5

Public Revenues......................................................................................................... 6

AN EVOLVING INDUSTRY............................................................................................... 6

BACKGROUND................................................................................................................. 7

P

ARTICIPATION IN GAMBLING ACTIVITIES .................................................................. 9

W

HO GAMBLES? .......................................................................................................... 11

REGULATION ................................................................................................................ 13

Electronic Technology is Morphing Gambling ...................................................... 14

CALIFORNIA’S GAMBLING INDUSTRY ......................................................................... 16

INDIAN CASINOS IN CALIFORNIA......................................................................... 17

THE BASIC LEGAL FRAMEWORK ................................................................................ 17

Tribal Gaming.......................................................................................................... 17

CLASS III INDIAN GAMING IN CALIFORNIA................................................................ 18

California State-Tribal Compacts for Class III Gaming........................................ 18

Where Indian Gaming Can be Located–the “Indian Lands” Requirement..........

24

THE GAMES .................................................................................................................. 32

Class I Games...........................................................................................................

33

Class II Games .........................................................................................................

33

Class III Games........................................................................................................ 35

T

HE REGULATORY FRAMEWORK................................................................................ 37

Tribal Regulation..................................................................................................... 37

State Regulation....................................................................................................... 38

Federal Regulation ..................................................................................................

42

California Lobbying and Campaign Contributions................................................

43

GAMING TRIBES AND REVENUES................................................................................. 44

ii California State Library, California Research Bureau

Restrictions on Expenditures................................................................................... 48

Non-Gambling Revenues......................................................................................... 49

TAXES AND REVENUE SHARING WITH STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS .............. 49

Commercial Casinos ................................................................................................

49

Indian Casinos .........................................................................................................

50

California ................................................................................................................. 51

State and Local Taxes.............................................................................................. 53

CALIFORNIA INDIAN TRIBES WITH CASINOS .............................................................. 55

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF INDIAN CASINOS.............................................. 67

On Tribes.................................................................................................................. 67

On Communities and Consumers............................................................................ 72

Environmental Impact............................................................................................. 78

Public Health Impact...............................................................................................

79

C

RIME........................................................................................................................... 81

Problem and Pathological Gambling...................................................................... 83

CALIFORNIA STATE LOTTERY.............................................................................. 87

BACKGROUND............................................................................................................... 87

COMPETITION, INNOVATION AND EXPANSION............................................................ 88

Video Lottery Terminals .......................................................................................... 89

Multistate Games...................................................................................................... 89

Internet Lottery Games............................................................................................ 90

REVENUES..................................................................................................................... 90

Displacement Effect.................................................................................................

92

P

UBLIC EDUCATION—CALIFORNIA’S STATE LOTTERY BENEFICIARY ..................... 93

CONSUMER IMPACT—PROBLEM GAMBLING.............................................................. 94

CALIFORNIA HORSE RACING.................................................................................

99

BACKGROUND............................................................................................................... 99

C

ALIFORNIA RACE TRACKS....................................................................................... 100

ACCOUNT WAGERING................................................................................................ 101

REGULATION .............................................................................................................. 102

R

ACINOS ..................................................................................................................... 103

R

EVENUES................................................................................................................... 104

County Fairs........................................................................................................... 105

California State Library, California Research Bureau iii

SOCIAL IMPACT.......................................................................................................... 105

CALIFORNIA’S CARD CLUBS ................................................................................ 107

BACKGROUND............................................................................................................. 107

P

OKER......................................................................................................................... 108

S

HARED STATE AND LOCAL CONTROL ..................................................................... 108

REVENUES AND TAXES ............................................................................................... 110

CRIME......................................................................................................................... 112

OWNERSHIP ................................................................................................................ 113

LOCATIONS................................................................................................................. 113

INTERNET GAMBLING............................................................................................ 121

BACKGROUND............................................................................................................. 121

PLAYERS ..................................................................................................................... 122

T

HE LEGALITY OF INTERNET GAMBLING IN THE UNITED STATES.......................... 123

An International Business.....................................................................................

124

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC COSTS OF INTERNET GAMBLING....................................... 125

SOCIAL IMPACTS OF GAMBLING........................................................................ 127

PROBLEM AND PATHOLOGICAL GAMBLING ............................................................. 127

Background............................................................................................................ 127

Clinical Definition.................................................................................................. 127

Prevalence .............................................................................................................. 128

Vulnerable Groups................................................................................................. 130

Electronic Technologies and Problem Gambling................................................. 133

Public Health Impacts ...........................................................................................

134

Social Costs ............................................................................................................

135

Prevention and Treatment ..................................................................................... 136

C

RIME......................................................................................................................... 139

Public Corruption .................................................................................................. 139

Financial Crimes....................................................................................................

140

Victim Crimes......................................................................................................... 140

Illegal Games.......................................................................................................... 142

H

EALTH ISSUES .......................................................................................................... 143

Smoking..................................................................................................................

143

Alcohol.................................................................................................................... 144

iv California State Library, California Research Bureau

ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF GAMBLING................................................................ 145

BACKGROUND............................................................................................................. 145

DIRECT EMPLOYMENT............................................................................................... 145

A Point of Comparison—Commercial Casinos....................................................

146

S

TATE AND LOCAL REVENUES................................................................................... 147

BANKRUPTCIES........................................................................................................... 148

APPENDIX A................................................................................................................ 151

ENDNOTES................................................................................................................... 157

California State Library, California Research Bureau 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report was requested by California Attorney General Bill Lockyer and provides an

overview of gambling in California since 1998,

*

including its social and economic

impacts. The report considers each segment of the gambling industry in a separate

chapter: Indian casinos, the state lottery, horse racing, card rooms and Internet gambling.

The final two chapters broadly examine the literature on the social and economic impact

of the gambling industry.

A FAST GROWING AND PROFITABLE INDUSTRY

Gambling is a major and fast-growing industry. Industry revenues in the United States

grew from $30.4 billion in 1992 to $68.7 billion in 2002, and increased from 0.48 to 0.66

percent of gross domestic product.

1

Gambling is a large industry in California, with about $13 billion in gross gaming

revenues in 2004. Indian casino gross gaming revenues were an estimated $5.78 billion,

card clubs took in about $655 million, the state lottery’s sales were nearly $3 billion, and

over $4 billion was wagered on horse races. Net revenues after prizes and operational

expenses are deducted were considerably less. Racetracks and horsemen kept about eight

percent ($302 million) and the state lottery’s net revenues were $1.09 billion; card club

and Indian casino net revenue figures are generally proprietary.

What is the potential of the gambling market in California? We know of no way to

produce a credible estimate. We simply have no experience with the phenomenon of

readily available and skillfully packaged gambling opportunities located relatively near to

California’s large population centers. We do know that gambling is growing very rapidly

in the state and that knowledgeable observers of the industry expect it to continue to

expand.

Indian casino gaming in particular has the potential to expand considerably in California.

Sixty-six of California’s 108 federally recognized tribes have tribal-state compacts to

operate gambling facilities, and 61 have gambling facilities. Another 67 California tribal

groups are petitioning the Bureau of Indian Affairs for recognition. As tribes gain federal

recognition, they have the right to establish reservation lands with federal approval, and

the potential to operate gaming facilities on those and other non-ancestral trust lands.

California tribal casinos earn the most revenue of tribal casinos in any state—an

estimated $5.78 billion in 2004, up from $3.67 billion in 2002. In 2004, the state’s 56

Indian gaming facilities had an estimated 58,100 gaming machines, 1,820 non-house

banked table games, and large bingo operations. Non-gaming revenues at California

Indian gaming facilities (hotels, restaurants, retail shops, etc.) in 2004, earned an

estimated $544.6 million, a seven percent increase from the previous year.

2

*

See Roger Dunstan, “Gambling in California,” California Research Bureau, 1997, and Roger Dunstan,

“Indian Casinos in California,” California Research Bureau, 1998, for our earlier analyses.

2 California State Library, California Research Bureau

Federally recognized California tribes which had tribal-state gaming compacts as of

October 2005, had 31,623 enrolled members in 2001 (the most recent data available from

the Bureau of Indian Affairs), about nine percent of all American Indians residing in

California. Indian gross gaming revenues averaged about $188,000 per gaming tribal

member in 2004.

STATE REGULATION

Gambling is government-regulated. Governments determine which kinds of gambling

are permitted, where gambling establishments may locate, their size, who may own them,

who may work for them, who may sell them supplies and what games they can offer. In

effect, governments grant monopolies to themselves (state lotteries) and limit other

gambling operations through regulation (Indian casinos, race tracks, card clubs),

providing a valuable asset to a relatively few enterprises.

Governments regulate gambling in part to reduce its negative impacts on society. In

order for a regulatory scheme to be effective, it must have the resources and structure to

effectively monitor and investigate potential problems. California’s regulatory structure

mixes responsibilities among a number of entities—the Lottery Commission, the

California Horse Racing Board, the California Gambling Control Commission, the

Division of Gambling Control in the Department of Justice, the Office of Problem

Gambling in the Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs, and the Governor. This

divided structure makes it hard for the state to develop and implement a unified

regulatory policy. Equally important, the state’s regulatory agencies do not have

sufficient resources to fully staff their responsibilities.

Technology is producing new and different forms of gambling, confounding old divisions

between industry sectors and challenging regulatory schemes based on those divisions.

In California, Indian casinos have bingo machines that look and operate like slot

machines. Racetracks take wagers from bettors around the world over the Internet. Card

clubs host poker tournaments and advocate for slot machines. The state lottery joins a

multi-state lottery that offers larger jackpots. Internet gambling, which only the federal

government can regulate, offers gambling at home without any intermediate provider.

This reality suggests that the state should regularly review its entire approach to gambling

regulation to ensure that it is as effective as it could be.

ECONOMIC BENEFITS AND SOCIAL COSTS

California’s gambling industry provides economic and employment benefits to many

Californians. Rural areas benefit economically when casinos attract gamblers from other

places and some of their money is spent outside the casino. In California, Indian casinos

also provide a new source of employment for residents in rural areas, since up to 90

percent of casino employees are non-Indians.

3

Casinos may purchase a variety of goods

and services from local firms.

California State Library, California Research Bureau 3

A 2003 study by San Diego County estimated the following economic impacts from

tribal gaming in the county.

4

• Creation of about 12,000 jobs, primarily for non-Indians, with an annual payroll

of $270 million.

• Purchases of $263 million in goods and services in 2001, including contracts with

over 2,000 vendors, most in the county.

• Contributions of over $7 million to community organizations.

A 2004 study of the impact of California Indian casinos by researchers at California State

University, Sacramento (CSUS), based on county-level data, found “…a modest

correlation between Indian casinos and [higher] county employment

rates…[and]…somewhat higher crime and higher rates of personal bankruptcy.”

Aggravated assault and violent crimes were correlated with a greater casino presence, as

were increased public expenditures (as additional $15.33 per capita) for law enforcement.

The study also found somewhat higher tax revenues, primarily generated by room

occupancy taxes and tobacco taxes. Since local jurisdictions cannot impose a room

occupancy tax on hotels located on an Indian reservation, the increased tax revenues were

most likely generated by hotels in surrounding communities.

5

These findings run parallel to a 2002 National Bureau of Economic Research study using

county-level data, which found that after the opening of a Native American casino

employment increased by about five percent in nearby communities, while crime and

bankruptcy rates increased by about ten percent.

6

Problem and Pathological Gambling

Most people gamble responsibly for recreation, but a certain number gamble excessively

and become problem and pathological gamblers, harming themselves, their families, and

their communities. As access to gambling--either state-promoted or authorized--

increases, the prevalence of problem and pathological gambling is also increasing. This

addiction creates social costs analogous to the impact of excessive alcohol or drug

consumption.

7

Problem gambling refers to gambling that significantly interferes with a person’s basic

occupational, interpersonal, and financial functioning. Pathological gambling is the most

severe form and is classified as a mental disorder with similarities to drug abuse

including “…features of tolerance, withdrawal, diminished control, and relinquishing of

important activities.”

8

Casino gambling generates 82.5 percent of all problem gambling helpline calls to the

California Council on Problem Gambling. Over three quarters of the callers give

California Indian casinos as their primary gambling preference, and five percent cite

Nevada casinos. Casino gambling is thus the predominant venue for problem gambling

in California.

9

4 California State Library, California Research Bureau

We use national prevalence figures to estimate that there are 589,000 adult problem

gamblers and an additional 333,000 adult pathological gamblers in California--nearly a

million people with a serious gambling problem.

Adolescents who gamble are more likely to develop problem and pathological gambling

behaviors, with lotteries and Internet poker as gateway games. Adolescent excessive

gambling can result in a number of long-term negative consequences including truancy,

dropping out of school, severed relationships with family and friends, and mental health

and behavioral problems including illegal behavior to finance gambling. If we apply

Oregon’s adolescent gambling problem/disorder prevalence percentages to California, we

find that 436,800 youth are problem gamblers and 159,900 youth have gambling-related

disorders with impairment--nearly 600,000 California youth have a serious gambling

problem.

High-risk groups, in addition to adolescents, include adults in mental health and

substance abuse treatment, who have rates of problem and pathological gambling four to

ten times higher than the general population.

10

Men have a prevalence rate two to three

times higher than women. Some ethnic groups are especially vulnerable to problem

gambling. For example, in California the Commission on Asian & Pacific Islander

American Affairs has identified problem gambling as a serious community concern.

• Prevalence increases considerably among adult casino gambling patrons—4.6

percent are problem gamblers and 5.4 percent are pathological gamblers. A study

by the National Opinion Research Center found that adults living within 50 miles

of a casino had double the probability of pathological or problem gambling.

11

• A study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that 3.6

percent of lottery patrons were problem gamblers and 5.2 percent were

pathological gamblers.

12

Lotteries are a key entry point into this disorder, given

their widespread and ready availability and state-sponsored legitimacy. Underage

youth have little difficulty in purchasing lottery tickets.

• Studies find that adults who bet on horse racing (both on and off-track) have the

highest incidence of problem and pathological gambling of any gambling patrons.

Fourteen percent are estimated to be problem gamblers and 25 percent are

pathological gamblers.

13

The California Horse Racing Board offers direct access

to companies that facilitate betting on horse races through its state website.

• Internet poker gambling among young males is extremely popular, and becoming

a problem. As an example, the president of the sophomore class at Lehigh

University robbed a bank in an attempt to pay off $5,000 in Internet gambling

debts.

14

Prohibitions against gambling by minors in California card clubs appear

to not be not well enforced.

• A study by the State of Oregon of gambling treatment and prevention programs

found that the primary gambling activity of gamblers enrolled in treatment was

video poker (74.5 percent), followed by slot machines (10 percent), cards (5.2

California State Library, California Research Bureau 5

percent), betting on animals (1.6 percent), Keno (1.5 percent), and bingo (1.4

percent).

15

Based on national estimates, the annual cost of adult pathological gamblers in California

is an estimated $489 million, and the annual cost of adult problem gamblers is an

estimated $509 million--nearly one billion dollars in total. These costs derive from a

number of social and personal problems that correlate with problem gambling including

crime, unpaid debts and bankruptcy, mental illness, substance abuse, unemployment and

public assistance.

California state prevention programs for problem and pathological gambling are just

getting underway, and there are no state-funded treatment programs. The state’s Office

of Problem Gambling in the Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs has a budget of

about $3 million. Based on an estimate provided by the California Council on Problem

Gambling, it would cost around $2.8 billion to offer all of the state’s adult problem and

pathological gamblers a six-week intensive treatment course, with follow-up at

Gamblers’ Anonymous. There currently are a very limited number of certified therapists,

so there would need to be investment in capacity-building first.

Crime

Research suggests that crime rises as casinos attract visitors who either commit or are the

victims of crime. This phenomenon may also occur in other attractions with cash-bearing

participants.

16

In addition, problem and pathological gambling increases among local

residents and is associated with crimes that generate money to gamble and/or pay off

gambling debts.

A study using data from every U.S. county between 1977 and 1996, found that casinos

(including Indian casinos and riverboat casinos) are associated with increased crime

(defined as FBI Index 1 Offenses: aggravated assault, rape, murder, robbery, larceny,

burglary, and auto theft) after a lag of three or four years. Prior to the opening of a

casino, casino, and noncasino counties had similar crime rates, but six years after casino

openings, property crimes were eight percent higher and violent crimes were ten percent

higher in casino counties.

Should casinos help pay for the public costs of these crimes? The authors of one study

estimate that taxes compensating for the casino-induced increase in FBI Index 1 crimes

would represent about 25-30 percent of casino revenues.

17

Casinos could plausibly also

be asked to address problem and pathological gambling. The authors of a Wisconsin

study made the following recommendations to the state as it renegotiated its tribal-state

gaming compacts:

18

• The tribes should fund enhanced law-enforcement activities in casino and

adjacent counties, including road patrols, especially in areas around bars.

• The tribes should fund community assistance, such as creating and activating

neighborhood-watch programs.

6 California State Library, California Research Bureau

• Tribes should not sell alcoholic beverages in their casinos.

• Drug-detection units of state police should be enhanced and made available to

sheriffs and police.

• Police officers and prosecutors in all counties should include gambling screening

questions in all arrest reports and crime reports.

Public Revenues

The gambling industry provides relatively modest revenues to state and local

governments.

• Under the 1999 tribal-state compacts, California gaming tribes make payments to

a Revenue Sharing Trust Fund for non-gaming tribes. Twenty eight tribes with

1999 compacts also contribute to a Special Distribution Fund that backfills

shortages in payments to non-gaming tribes, with the remainder appropriated by

the legislature. Under 2004 amended compacts, six tribes make payments to the

General Fund. Five years of all these payments (2000-2005) are the equivalent of

about nine percent of the Indian gaming revenues earned in four years (estimated

gaming revenues for 2000 are not available).

• Net lottery revenue contributed about one percent of total California state

revenues in FY 2004-05, and about three percent of the amount that the state

spent on public education.

• In 2004, the state received $39.5 million in licensing fees and breakage

*

(1.03

percent) from California horse races and local governments retained more than $7

million (0.19 percent).

• Fees paid by card clubs to the state have held steady over the last eight years and

have declined when inflation is taken into account; in contrast, revenues have

increased by 75 percent.

AN EVOLVING INDUSTRY

Although we have made every effort to review recent data on gambling in California and

the nation, the industry is constantly evolving. Thus the reader is advised to check recent

news articles and state reports for updated information.

*

“Breakage” is the odd cents not paid to winning ticket holders.

California State Library, California Research Bureau 7

THE GAMING INDUSTRY

B

ACKGROUND

Gambling has a long history in human affairs--at times associated with sin and corruption

and at other times considered a form of entertainment. Societal responses have ranged

from strict prohibition to legal acceptance.

19

Various groups and individuals hold the full

range of those views today, so controversy will certainly continue. Nonetheless,

gambling revenues are a major source of funds for governments, charities and businesses

throughout the world, gambling is a major industry that employs thousands of people,

and it is an enjoyable entertainment for many people.

Studies in the United States suggest that religious differences and the availability of

gambling in neighboring jurisdictions affect the permissiveness of state gambling laws.

20

All states except Hawaii and Utah have authorized at least one form of gambling, as

summarized in Table 1.

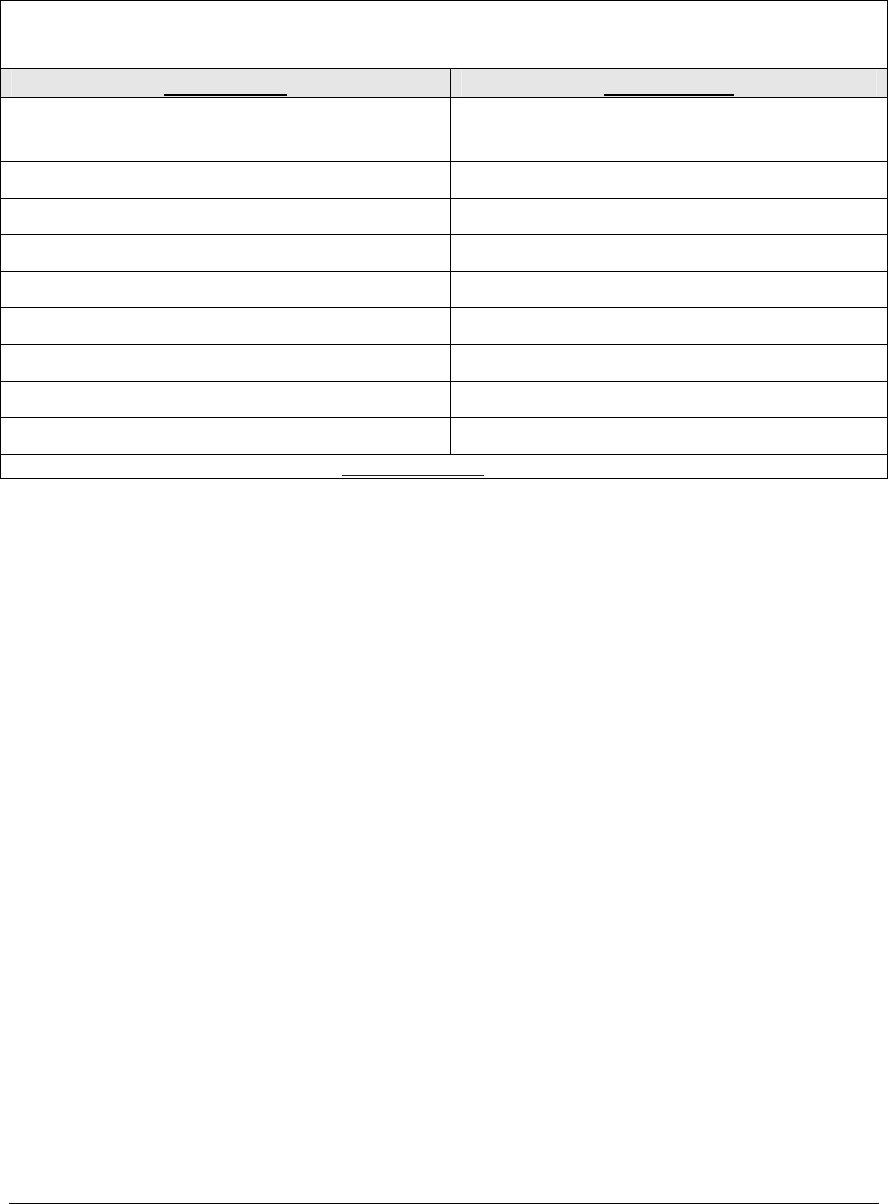

Table 1

Number of State Permitting 21 Different Forms of Gambling (2003)

# States

Permitting

# States

Permitting

Charitable Bingo

46

Indian Casinos 22*

Thoroughbred Wagering 43 Greyhound Racing 19

Inter-Track Wagering 42 Telephone Wagering 17

Charitable Games 41 Keno Style Games 15

Instant Pulltabs 40 Casinos and Gaming 14

Lotto Games 40

Card Rooms

13

Quarter Horse Wagering 37 Non-Casino Devices 6

Numbers Games 36 Video Lottery 6

Harness Racing 34 Jai Alai 4

Indian Bingo 30 Sports Betting 4

Off-Track Wagering 25

* 30 as of 2005.

Sources: Taggart and Wilks, Gaming Law Review, November 2005, drawn from McQueen,

International Gaming & Wagering Business, 2003, and Alan Meister, Indian Gaming Industry Report,

2005-06 edition.

Gambling revenues in the United States grew from $30.4 billion in 1992 to $68.7 billion

in 2002, and as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) increased from 0.48 to

0.66 percent over that period.

21

State governments have benefited from gambling

revenues, which in 2000 transferred $26.8 billion to state coffers (although the net effect

8 California State Library, California Research Bureau

is likely less due to displaced spending from other taxable sales, as discussed).

22

Even

charities increasingly rely on poker tournaments and casino gaming as fundraisers, which

pending legislation in California would legalize.

23

Over a ten-year period, from 1994 to 2004, the gross gambling revenue earned by the

legal gambling industry doubled in the United States.

*

In 2004, consumer spending

increased by seven percent from the previous year to $78.6 billion. This was more than

consumers spent on movie tickets, recorded music, theme parks, spectator sports, and

video games combined.

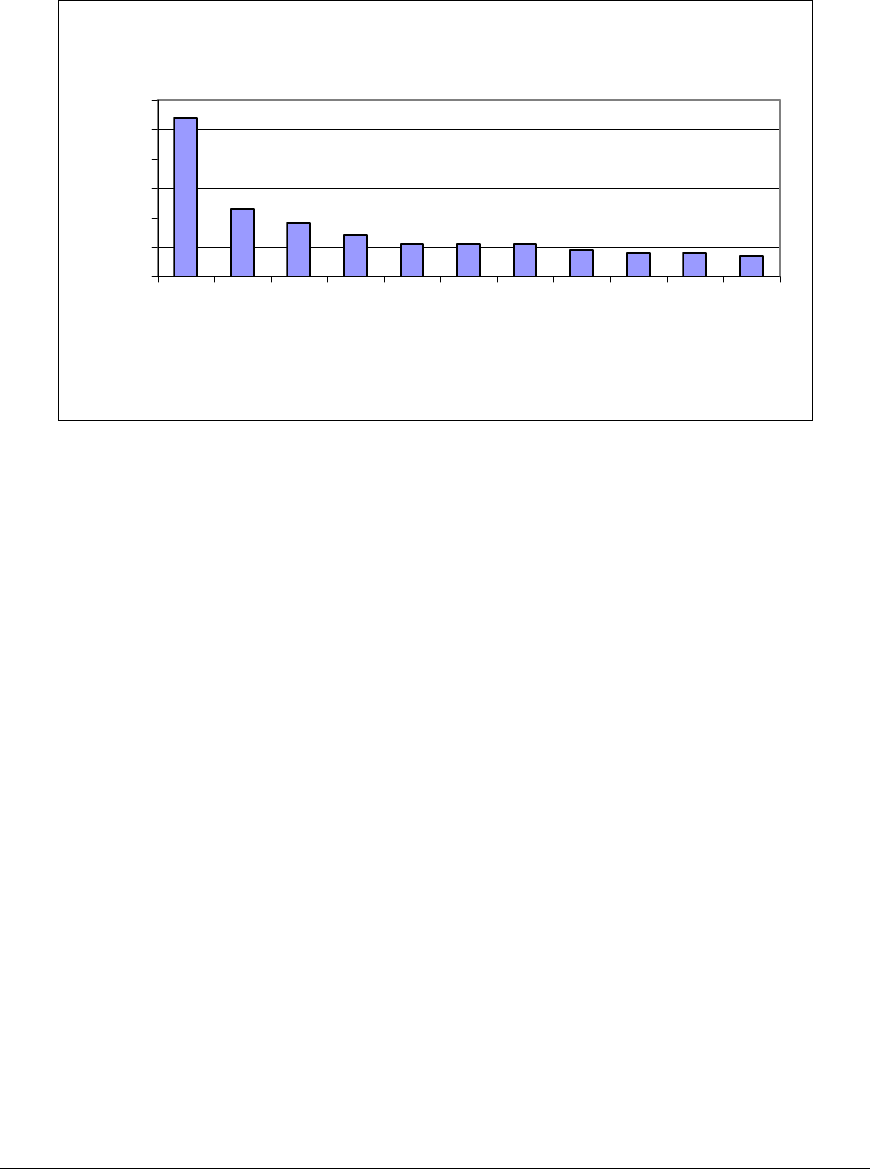

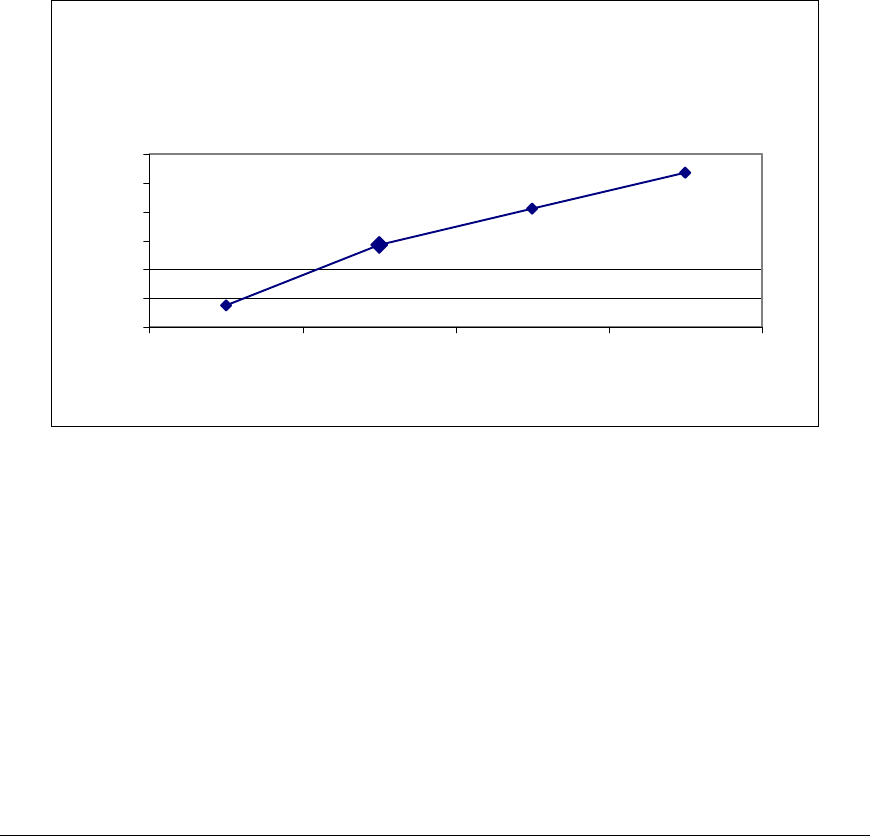

Figure 1

Total Legal* Gross Gambling Revenue in the U.S.

1994-2004 (in $billions)

$0.00

$10.00

$20.00

$30.00

$40.00

$50.00

$60.00

$70.00

$80.00

$90.00

1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Year

Revenue in $billions

Source: American Gaming Association

*Includes horse racin

g

, lotteries, commercial & Indian casinos, bin

g

o, card rooms, le

g

al bookmakin

g

, charitable

Indian gaming is the most important growth sector of the U.S. gambling economy, with

gross revenues doubling from $9.6 billion in 1999 to $19.4 billion in 2004. California’s

Indian casinos accounted for about half of that increase, generating more revenue than

gaming tribes in any other state. Experts predict that there is room for substantial growth

in the future. Indian gambling enterprises are rapidly expanding into related businesses,

such as hotels and restaurants that attract gamblers and keep them playing.

Table 2 shows that the gambling industry in the United States grew considerably from

1999 to 2003. Indian casino gaming revenues increased by 75 percent. Estimated global

Internet gambling revenues increased by an amazing 487 percent from 1999 to 2003

†

.

Decreased horse racing and card room revenues were due in part to competition from

casinos and Internet gambling, although card room revenues increased again in 2004,

according to the American Gaming Association, driven by the popularity of poker. Card

room revenues in California were an exception to the national trend, increasing by nearly

60 percent from 1999 through 2004 (see Figure 17, page 111).

*

Gross gambling revenue is the amount wagered minus the winnings returned to players.

†

The most recent estimate (2006) estimate by the American Gaming Association is that Internet gambling

is a $7 billion to $9 billion market in the United States, and growing.

California State Library, California Research Bureau 9

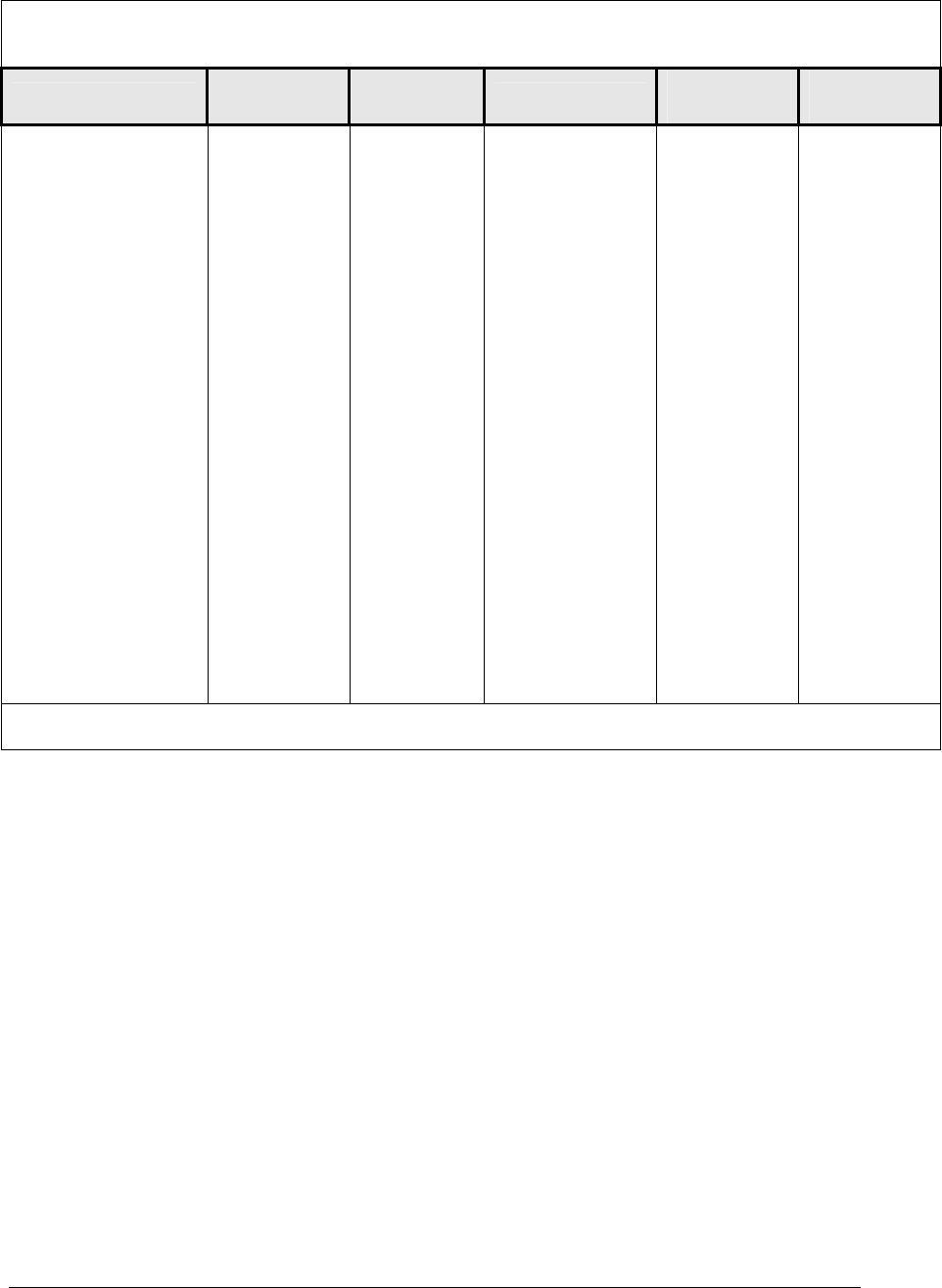

Table 2

1999, 2002 and 2003 Gross Revenues by Gambling Industry (U.S.) (in $ millions)

1999 Gross

Revenues

2002 Gross

Revenues

2003 Gross

Revenues

% Change

1999-2003

Horse Racing

$3,382.9 $3,445.5 $3,362.4 -1%

Lotteries (except

Video)

$14,952.8 $16,237.7 $17,351.2 16%

Casinos (Land &

Water)+

$24,888.4 $27,858.6 $28,689.4 15%

Indian Casinos*

Class II $1,149.8

Class III $8,454.9

Total $9,614.7

Class II $1,753.9

Class III $12,718.4

Total $14,472.3

Class II $2,018.5

Class III $14,802.6

Total $16,821.2

75%

Card Rooms

$909.3 $973.3 $851.3 -6%

Charitable Games

$1,417.7 $1,508.4 $1,559.7 10%

Internet Gambling

(Global)

$1,167 $4,007 $5,691.4 487%

+Except for commercial casinos, the industries presented are legal in California.

*Indian gaming revenues in 2004 were $19.4 billion, according to the National Commission on Indian

Gaming.

Source: International Gaming & Wagering Business, August 2001 and September 2004.

Table 2 shows gross revenues, which is the total amount wagered minus money returned

to players. In competitive gaming markets, more revenues must go into prizes, limiting

the industry’s revenues. The amount of money actually earned by a gambling enterprise

(the “take-out rate”) is gross revenues minus operational expenses.

In some states, gambling businesses operate in a variety of markets. For example, casino

companies and Native American tribes own and operate racetracks, casinos, and lotteries

and offer keno and table games, including poker, as well as slot and video gaming

machines. There are casinos on cruise ships and soon will be on airplanes.

24

PARTICIPATION IN GAMBLING ACTIVITIES

A December 2003 Gallup Lifestyle Poll found that two-thirds of Americans had gambled

in the previous 12 months. State lotteries were the most common form of gambling:

25

• 49 percent had purchased a lottery ticket

• 30 percent had visited a casino

• 15 percent had participated in an office pool

• 14 percent had played a video poker machine

• Five percent had played bingo for money

10 California State Library, California Research Bureau

• Four percent had bet on the horse races

• One percent had gambled for money on the Internet (a number that has

undoubtedly increased since 2003).

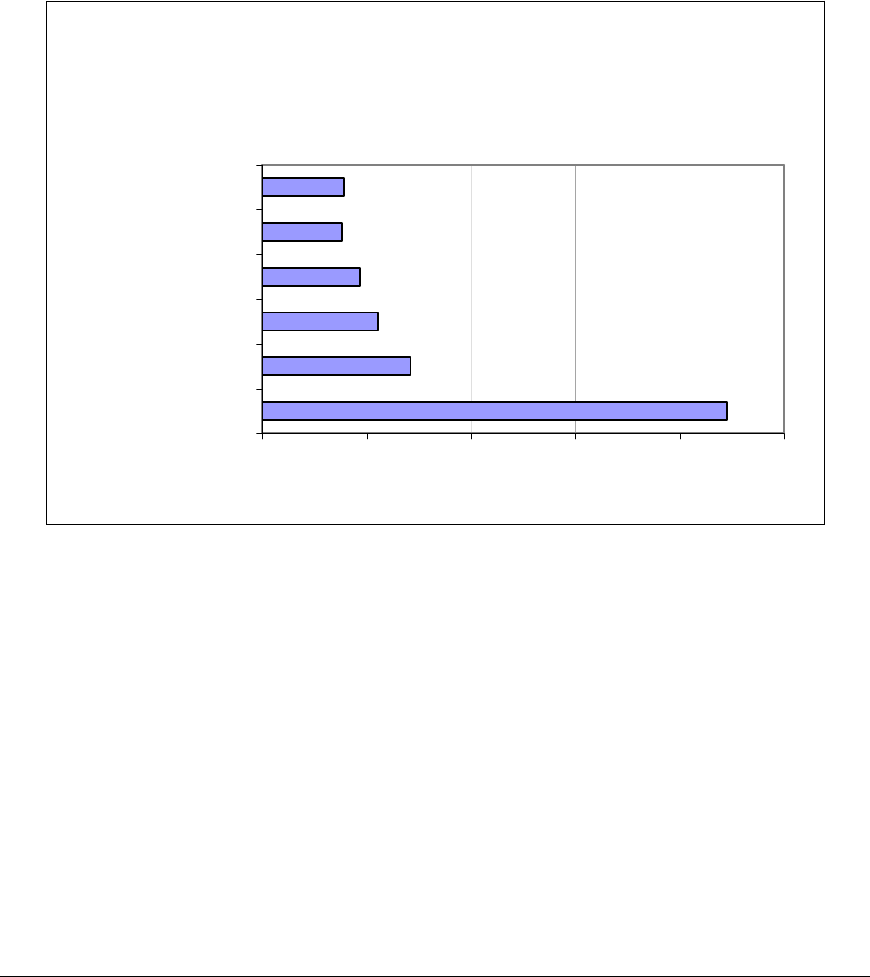

Figure 2

Participation in Gamblin

g

Activities Over Previous 12

Months, in 1989, 1996 and 2003

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Bing

o

Ca

s

ino

Ho

r

s

e

Race

Sta

t

e

Lott

e

ry

Profession

a

l s

p

ort

s

Offic

e

p

o

ol

I

n

t

e

rne

t

Vide

o

p

o

ker

1989

1996

2003

Source: Gallup Poll, 2003.

As Figure 2 shows, national participation in casino gambling increased from 20 percent

in 1989 to 30 percent in 2003, while participation in other types of gambling decreased.

A study by Harrah’s Entertainment found that more than a quarter of Americans over age

21 gambled at a casino in 2002, on average once every two months. The same survey

found that California’s 2002 casino participation rate was 38.3 percent, with 5.4 average

trips per year. Indian casinos in Southern California were the top destination (33 percent

of trips), followed by Las Vegas (21 percent of trips).

26

Half the people who gamble do so to win money, and as many gamble for entertainment

and excitement.

27

Nevertheless, the gambling industry as a whole suffers from a negative

public image, according to a 2004 survey, which found that “trustworthiness” and a

negative public image were the biggest challenges facing the industry. In comparison,

gambling companies identified their biggest challenge as offering a broad range of secure

payment methods.

28

A poll by Harrah’s Entertainment in 2002 found that casinos are “…perceived as a sin

industry with deep pockets—much like tobacco, alcohol and pharmaceutical

corporations---and therefore an attractive source of increased taxes.” Only 23 percent of

those polled had a positive perception of the casino industry and 99 percent said they

would target casinos as a source for additional tax revenue.

29

California State Library, California Research Bureau 11

WHO GAMBLES?

According to a recent article in The Atlantic Monthly, a record 73 million Americans

visited one of 1,200 gambling businesses in the last year, a 40 percent increase from five

years ago, and a quarter of American adults list gambling as their first entertainment

choice.

30

A 2004 Los Angeles Times poll found that 40 percent of Californians said that

they or a family member had visited an Indian casino in the past year.

31

The data presented in the following figures is drawn from a March 24, 2004, Gallup Poll

and from a survey conducted by Harrah’s Entertainment.

32

Gallup found that nearly

seven out of ten American adults and 26 percent of teenagers took part in some form of

gambling in 2003 (in most states it is not legal for teenagers to gamble).

Figure 3

Gender of Americans Gambling in the Previous Year (2003)

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

Men Women

Source: Gallup Poll, 2004.

More men than women gamble. Older Americans are more likely to gamble than young

adults. The median age of all U.S. adult gamblers is 45 years old. A 1995 Las Vegas

Visitor Profile Study found that nearly half of casino patrons were 50 years or older; 30

percent were over 60.

33

12 California State Library, California Research Bureau

Figure 4

Age of Americans Gambling in the Previous Year (2003)

56%

58%

60%

62%

64%

66%

68%

70%

18-29 30-49 50-64 65+

Percent

Source: Gallup Poll, 2004.

College-educated adults are more likely to gamble than adults who completed high

school or have less than a high school education. The Harrah’s survey found that the

typical casino customer is slightly more likely to have attended college than the average

American (55 percent versus 53 percent). However the relative amount gambled by these

groups varies. For example, a 1999 study found that while high school dropouts and

college graduates participated equally in lotteries, the dropouts spent $334 per capita

while the average college graduate had bought just $86 of lottery tickets.

34

Figure 5

Education of Americans Gamblin

g

in the Previous Year b

y

Subgroup (2003)

63%

64%

65%

66%

67%

68%

69%

70%

71%

72%

High school or less College

Percent

Source: Gallup Poll, 2004.

People who earn more money are more likely to gamble. According to the Harrah’s

survey, the median 2004 household income of U.S. casino customers was $55,322.

However most economic studies have found that gambling expenditures are regressive

California State Library, California Research Bureau 13

because the poor spend a higher proportion of their income on gambling than do the rich.

In general the poor, racial minorities and less educated Americans spend considerably

more per capita on gambling. In the 1999 study cited above, households with incomes in

the $50,000 to $99,000 range participated in lotteries at a higher rate (61.2 percent) than

poor households with less than $10,000 in income (48.5 percent). However the poorer

households spent $520 on lotteries in a year compared to $301 for the richer households.

Figure 6

Income of Americans Gambling in the Previous Year (2003)

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

Earned less than $30,000 Earned more than $70,000

Percent

Source: Gallup Poll, 2004.

Americans have mixed opinions about gambling. According to a 1999 Gallup Poll, 56

percent agreed that casinos have a negative impact on family and community life in the

cities in which they operate, even though two-thirds agreed that gambling had helped the

local economy. Only 22 percent of Americans said that gambling should be expanded,

nearly half (47 percent) wanted it to stay at current levels and 29 percent believed it

should be reduced or banned.

35

Although the national gambling polls cited above do not present information about the

ethnicity of gamblers, in California Asian-Americans are highly represented among

recreational gamblers: “Asian Americans make up some 50 percent of the clientele at

Pechanga Resort & Casino and a large part of the clientele at other casinos. These

casinos are seeking to attract …coveted Asian–American customers…and are doing

everything from advertising in ethnic publications and hiring multilingual hosts, to

offering Asian-American entertainment and in one case redesigning parts of the casino

with Asian themes.”

36

REGULATION

Whether to allow gambling, what types of games, and in what locations--these are

contentious issues in many states. The gaming industry is highly regulated as to where

and how it can operate and what games it can offer. Gaming enterprises aggressively

seek to increase their market share by lobbying political jurisdictions to expand into new

locations, discourage competition, and extend regulatory boundaries to offer newer and

14 California State Library, California Research Bureau

more profitable games. For example, horse racing tracks and cardrooms have been

urging states to allow them to install slot machines in their facilities, with some success

(although not in California)

.

According to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission, state and federal

gambling laws and regulations support the following common goals:

37

• Ensure the integrity of the games

• Prevent links with criminal activity

• Limit the size and scope of gambling

The extent to which gambling can expand in a relatively unregulated market may be seen

in Russia, which after years of prohibition now has few regulatory restrictions, cheap

licensing and low tax rates ($150 to $250 a month per slot machine). Moscow has one

slot machine for every 290 inhabitants housed in more than 53 gambling halls and 2,000

arcades.

38

Electronic Technology is Morphing Gambling

Electronic gaming and new communication technologies are rapidly erasing the divisions

between games and locations on which many state and federal gambling laws and

regulations are based. The challenges to regulators to define gaming limits are

continuous given the pace of technological innovation. Large potential profits encourage

gaming enterprises to push at the laws’ limits. For example:

• Rapid Roulette uses a physical wheel and live dealer but touch screen technology

that allows players to place bets via a video screen from remote locations.

• In video poker games based on blackjack, the most popular American table game,

each player has a video screen and there is often a live dealer, using real chips,

running the game.

• Electronic bingo is virtually indistinguishable from a slot machine from a player’s

perspective, the difference being that multiple players are linked electronically.

Examples of recent advisory opinions issued by the California Department of Justice’s

Division of Gambling Control include:

“Ultimate Bingo Game System Considered to be a Slot Machine”

39

“Volcanic Bingo Advisory”

40

“California Roulette and California Craps as House-Banked Card Games”

41

Electronic gaming technologies have led to controversies involving multiplayer

electronic units modeled on table games. Several California Indian tribes counted

multiplayer units tied to a single server as one “slot machine,” placing more terminals in

their casinos than allowed under their tribal-state compact. A survey by the Division of

California State Library, California Research Bureau 15

Gambling Control and the California Gambling Control Commission found nearly 300

terminals attached to multiplayer games in casinos around the state. The Attorney

General defined each terminal as a gaming device and the tribes had to remove the extra

machines after the federal district court agreed.

42

Internet and wireless communications technologies challenge existing gambling markets

and state and federal regulatory schemes. For example, bettors can play poker and wager

on horses online, bypassing traditional card rooms and the pari mutuel wagering that

supports horse racing. These communication technologies support multistate lotteries

and allow bingo games to be hosted at multiple sites, creating larger prizes and more

competitive games. International gambling companies headquartered in other countries

compete in the American gambling market via the Internet, even though it is illegal.

Some analysts contend that the gambling industry is facing a shake-up similar to the

challenge that Napster and other file-sharing programs have posed for the music and

movie industries.

Charitable Games

Even nonprofit organizations are pushing at the edges of legal gambling in California.

43

Some organizations recently received notice from the California Division of Gambling

Control that poker tournaments and casino gambling nights are illegal fundraisers.

Organizers could face up to a year in jail or a fine of $5,000. This is because only

licensed card rooms or tribal casinos with state-tribal compacts are permitted to host

games such as poker or Monte Carlo-style gambling in California. Pending legislation

may legalize a limited number of casino-themed fundraisers for nonprofit organizations.

*

Currently, non-profit organizations in California may host bingo games and raffles.

Charities must register with the Attorney General’s Registry of Charitable Trusts prior to

conducting a raffle, and report afterwards. Charities operating bingo games must comply

with local ordinances regulating days, locations, and hours of operation. Local

governments may charge a licensing fee for bingo games.

Charitable bingo can be a big business, as in the case of the Hawaiian Gardens Bingo

Club, which is the largest non-tribal bingo parlor in the state, operating seven days a

week. Between 1997 and 2003, the club brought in more than $200 million in revenue

and paid out almost $37 million in charitable giving. Some of the proceeds have gone to

local charities, but considerable controversy has accompanied many of the grants to

groups in Israel. Under California law, bingo halls must be staffed by volunteer workers,

so the bingo hall’s workers rely on tips from players. Next door to the bingo hall, and

under the same management, is Hawaiian Gardens Casino, the state’s largest card room,

*

AB 839 (Torrico) would allow registered charitable organizations to hold one casino-night fundraiser a

year, including poker and pai gow games, with at least 90 percent of the gross revenues going to the

charity. Players must be over 21, and cash prizes are prohibited. Any single prize could not exceed $500

in value, or total prizes exceed $5,000. In addition, no more than four events could be held in any one

location a year. The nonprofit organization would need to register with the Division of Gambling Control

in the Department of Justice and pay a fee, and vendors would need to be licensed by the California

Gambling Control Commission. (2/2/06 version).

16 California State Library, California Research Bureau

with 1,675 employees, 180 tables, and expected revenues of $85 million this year.

According to press accounts, the club plans to expand to 300 tables by the end of the

year. The club provides nearly 80 percent of the city’s general fund budget (almost $10

million a year).

44

The flow of revenue to some nonprofit organizations from bingo games has shrunk since

casino gambling on Indian lands became widespread in California. For example,

Sacramento County charity bingo hall revenues have dropped by nearly one third in the

last 12 years. Ride to Walk, a Placer county charity that at one time earned $150,000 a

year from its weekly bingo night, lost $6,600 last year, reportedly due to competition

from nearby Thunder Valley Casino.

45

CALIFORNIA’S GAMBLING INDUSTRY

Gambling was limited to card rooms, racetracks and charitable bingo for most of the

state’s history. Now the state has a lottery and allows slot machines and Nevada-style

house-banked card games in Indian casinos. The state’s voters approved a casino

gambling monopoly for California’s federally recognized Indian tribes in March 2000,

and validated that decision again in 2004, when they defeated an effort to expand slot

machines and other casino games to card rooms and race tracks. Californians also

participate in charitable gambling, including raffles and bingo. Cruise ships with casinos

sail from Los Angeles and San Diego on short trips to Baja California and back. There is

considerable illegal gambling, including cockfighting, and betting on sports games. In

short, gambling is a major industry and activity in California.

California’s gambling industry earned over $13 billion in gross gaming revenues in 2004.

Indian casino gross gaming revenues were an estimated $5.78 billion, card clubs took in

about $655 million, the state lottery’s sales were nearly $3 billion, and over $4 billion

was wagered on horse races. Net revenues after prizes and operational expenses are

deducted were considerably less. Racetracks and horsemen kept about eight percent

($302 million) and the state lottery’s net revenues were $1.09 billion.

What is the potential of the gambling market in California? We know of no way to

produce a credible estimate. We simply have no experience with the phenomenon of

readily available and skillfully packaged gambling opportunities located relatively near to

California’s large population. We do know that gambling is growing very rapidly in this

state, and that knowledgeable observers expect it to continue to expand.

This report is divided into sections, each of which focuses on a different segment of

California’s gambling industry, principally since 1999.

*

Whenever possible we provide

state-level data along with comparative national information. The report also examines

research findings about the economic and social impact of gambling in California and

other political jurisdictions.

*

See California Research Bureau reports by Roger Dunstan and the National Gambling Impact Study

Commission for more detailed earlier data.

California State Library, California Research Bureau 17

INDIAN CASINOS IN CALIFORNIA

T

HE BASIC LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Several key principles underlie the special legal status that American Indian tribes enjoy

in the United States. Most importantly, tribes are sovereign political entities with

“inherent” rights that preceded European colonization, were recognized in treaties with

the colonies and then the federal government, and continue today. The tribes are

“…distinct political entities both protected by and subject to the laws and policies of the

national government.”

46

Article I, Section 8 (3) of the U.S. Constitution reserves the power to regulate commerce

with Indian tribes to the Congress. Thus tribal status can be modified by Congress but

state laws do not apply to the tribes unless Congress consents.

Tribal Gaming

Tribal gaming as an economic development tool began with high-stakes bingo games

offered by the Seminole and Miccosukee tribes in Florida in the 1970s. In California, the

Cabazon and Morongo Bands of Mission Indians launched card games and bingo in their

casinos approximately 25 years ago, leading to a dispute with county and state authorities

and threatened criminal action. The legal basis of the dispute was anchored in Article IV,

Section 19 (e) of California’s Constitution, which prohibits casino operations:

The Legislature has no power to authorize, and shall prohibit casinos of the type

currently operating in Nevada and New Jersey (adopted by initiative, 1984).

In 1987, the United States Supreme Court found in California v. Cabazon Band of

Mission Indians (480 U.S. 202, 1987) that federal law authorized gaming on federally

recognized tribal lands and that the state did not have civil regulatory authority to

proscribe gaming on those lands. The court further reasoned that since the state already

allowed local communities to authorize card rooms and charity bingo games, these games

did not violate the general public policy of the state and were therefore allowed on tribal

lands. Indian gaming is conducted by tribal governments as an exercise of their

sovereign rights.

In response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Cabazon, Congress enacted the Indian

Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) to provide a statutory basis for the operation of gaming

by Indian tribes on Indian lands, “…as a means of promoting tribal economic

development, self-sufficiency, and strong tribal governments…”

47

IGRA created a

comprehensive regulatory framework, dividing Native American gaming into three

categories or classes, each of which differs as to the extent of federal, tribal and state

oversight. IGRA also established the National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC) to

exercise general regulatory oversight.

While class I traditional and social games are subject only to tribal government

regulation, and class II games such as bingo are subject to tribal and federal oversight,

18 California State Library, California Research Bureau

class III casino-type gaming is regulated by the tribes, states and the federal government.

In order for tribes to operate casino-type class III games, IGRA requires that a tribal-state

compact be adopted. A tribe that wants to conduct class III gaming must formally

request that the state enter into compact negotiations. Once approved by the state, the

compact must be submitted to the Department of the Interior, which has 45 days to

approve (sign or take no action) or disapprove it. NIGC approval is also required for

tribal gaming ordinances and casino management contracts.

CLASS III INDIAN GAMING IN CALIFORNIA

Between 1990 and 1992, the State of California, through the California Horse Racing

Board, entered into four compacts with federally recognized tribes to allow off-site

betting on horse races on their lands. (The Board no longer has statutory authority to

negotiate with tribes on behalf of the State.)

Then-Governor Wilson was resistant to expanding casino gambling to tribal lands.

Nonetheless, some tribes installed a variety of video pull-tab games (under the legal

theory, since disproved by the courts, that they were class II games) and nonbanked

versions of Nevada casino games, leading to numerous legal actions.

In 1996, some California tribes had an estimated 496 table games and 14,407 video slot

machines in their casinos, taking in more than $652 million.

48

Thus there was large-scale

class III gaming but no tribal-state compact as required by federal law, a violation of

IGRA and the federal Johnson Act.

Also in 1996, in Seminole vs. Florida, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down as

unconstitutional a provision in IGRA that permitted tribes to sue a state for failure to

negotiate a compact in good faith. This decision increased states’ negotiating leverage

with tribes desiring to establish and/or expand gambling operations on their lands, and

“…set the stage for highly politicized compact negotiations.”

49

It is not clear, outside

California, that a tribe has an effective legal remedy should a state refuse to negotiate a

compact.

*

California State-Tribal Compacts for Class III Gaming

In 1998, Governor Wilson entered into a compact with the Pala Band of Mission Indians,

a non-gaming tribe, after 17 months of negotiations, permitting specific types of class III

gaming on tribal lands. Ten other tribes subsequently signed similar agreements, which

were approved by the legislature in August 1998. However other tribes found the

compacts’ provisions to be intrusive into traditional Indian sovereignty and circulated an

initiative to essentially overturn the Pala compact. Concurrently the U.S. Department of

*

Department of Interior regulations establish a mediation process, but whether a compact could be

imposed on a state is open to constitutional challenge under the Tenth Amendment. However California

has waived its immunity to suit under IGRA (Gov. Code §98005; H.E.R.E. v. Davis (1999) 21 Cal.4

th

585,

615-616.)

California State Library, California Research Bureau 19

Justice had forfeiture and injunction actions underway to seize tribal slot machines from

gaming tribes operating without tribal-state compacts.

In November 1998, California voters approved Proposition 5, the “Tribal Government

Gaming, and Economic Self-Sufficiency Act of 1998,” by 63 percent. The initiative

sponsored by the tribes authorized the full range of gambling on Indian lands in the state.

At that time, this was the most expensive initiative campaign in U.S. history, with the

tribes investing nearly $70 million in support and Nevada casinos $26 million in

opposition. However since Proposition 5 was a statutory initiative, and the prohibition

against casino gambling was in the state’s Constitution, the state Supreme Court found

the initiative to be unconstitutional in a 1999 decision.

Nonetheless, a number of tribes continued to operate an estimated 20,000 slot machines

in about 40 casinos. Christiansen Capital Advisors estimated that California tribal

casinos generated between $800 million and $1 billion in gross gambling revenues in

1999, while operating in a questionable legal environment that impeded ready access to

capital for facilities.

50

Many of the slot machines were supplied by companies under

revenue-sharing agreements.

In March 2000, two-thirds of the state’s voters voted in favor of Proposition 1A, which

was placed on the ballot by the governor and the legislature and supported by more than

80 of the state’s 108 federally recognized tribes.

51

Proposition 1A authorized the

governor, with the approval of the legislature, to negotiate and conclude compacts for the

operation of slot machines, lottery games and banking and percentage card games by

federally recognized Indian tribes on Indian lands. Proposition 17, passed in the same

election, enabled the legislature to authorize private, nonprofit organizations to conduct

raffles [California Constitution, Article IV, Section 19(f)]. The adoption of Proposition

1A provided a legal basis for tribal gaming in California.

In anticipation of the passage of Proposition 1A, in September 1999, Governor Davis and

58 of the state’s 108 federally recognized tribes signed 20 year compacts giving the tribes

a monopoly on slot machines and house-banked card games in the state. Sixty-one tribes

ultimately signed the compacts, which were ratified by the legislature. In 2003, the Ninth

U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found Proposition 1A to be constitutional.

In 2004, an initiative sponsored by card rooms and horse tracks (Proposition 68) to allow

card rooms and five tracks to have slot machines was defeated, receiving only 16.3

percent of the vote after the sponsors spent $27 million. Proposition 70, sponsored by the

Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians and several other Southern California tribes to

expand Indian gaming, was also defeated in that election. Sponsors spent $30.6 million.

The Proposition 1A Compact

The 37 page tribal-state gaming compact negotiated by Governor Davis and tribal leaders

in September 1999, was hastily drafted over a 16 day period, with no public hearings or

review. The compacts authorized the tribes to use up to 350 slot machines each, or more

if they had more in operation as of September 1, 1999. Tribes could also purchase

20 California State Library, California Research Bureau

licenses to use as many as 2,000 machines. They could establish and operate up to two

gaming facilities, offering slot machines and house banked card games. In addition, the

tribes could offer class II games (bingo etc.), which the state does not regulate. The

compacts were among the first in the nation to contain payments for non-gaming tribes,

and to allow collective bargaining among casino employees.

The compact, signed by 61 tribes, has been subject to varying interpretations, sometimes

resulting in litigation. Key terms are vague, leading to disputes such as over the number

of slot machines allowed, which ranged from Governor Davis’ figure of 45,000 to the

Legislative Analyst Office’s estimate of 113,000. The California Gambling Control

Commission eventually placed the number of authorized slot machines at 61,957. As

shown in Figure 7, the state’s Indian casinos currently have around 58,100 slot machines

in operation (although 66,507 have been authorized by the Commission), as well as 1,820

table games.

Figure 7

Gaming Machines in California

Indian Gaming Facilities

58,100

55,603

47,186

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

2002 2003 2004

Machines

Source: Alan Meister, Casino City’s Indian Gaming Industry Report, 2005-2006 Updated Edition.

The compacts established a Revenue Sharing Trust Fund (RSTF), which is funded by

fees paid by gaming tribes with licensed slot machines for distribution to non-compact

tribes (defined as tribes with less than 350 slot machines). The compacts provide that

non-gaming tribes are to receive $1.1 million annually. As of September 2005, $148

million had been distributed to eligible tribes. Including interest, payments to the fund

totaled $154.6 million.

Tribal contributions do not generate sufficient revenue to allow the RSTF to provide $1.1

million annually to all non-gaming tribes, resulting in an aggregate shortfall to all eligible

recipient Indian tribes in fiscal year (FY) 2004-05, of $48,483,757, or $692,625 per

tribe.

52

Government Code §12012.90 provides that the shortfall is to be paid from the

Special Distribution Fund (SDF) through the state budget process.

California State Library, California Research Bureau 21

The 1999 compacts provide that up to 13 percent of net win

*

from slot machines in

operation on September 1, 1999, is contributed to the SDF. Tribes that did not have these

gaming devices in operation prior to September 1, 1999, are not obligated to pay into the

SDF. The funds can be appropriated by the legislature through the budget process for

any purpose including, but not limited to, gambling addiction programs, reimbursement

of regulatory costs, grants to state and local governments impacted by gaming, and to

cover shortfalls in the RSTF. Payments to the SDF began in 2003, and totaled $368.7

million (including interest) through September 2005. The fund has a balance of about

$92.9 million for FY 2005-06.

The 1999 compacts will expire at the beginning of 2021. However they provide for

renegotiation at the request of either tribal leaders or the governor under specific

circumstances. These include unresolved environmental issues in the development of a

gaming facility, and/or a tribe’s desire to operate more than the 2,000 gaming devices

allowed by the compact. The compacts were opened for renegotiation over

environmental issues in 2003, but Governor Davis sent a letter to tribes rescinding his

formal request to renegotiate before he left office later that year.

In 2003, three tribes, the La Posta Band of Mission Indians, the Santa Ysabel Band of

Mission Indians and the Torres-Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indians negotiated tribal–state

gaming compacts with the Davis Administration that introduced revenue-sharing with the

state (payments to the General Fund) for the first time. These compacts also contain

stronger environmental language, requiring tribes to reach agreements with local

governments on off-reservation impacts.

The La Posta and Santa Ysabel compacts provide that five percent of the net win from up

to 350 gaming devices will go to the state, and that the tribes will enter into memoranda

of understanding with local governments to mitigate the impact of their casinos. The

Torres-Martinez compact creates a sliding scale beginning with three percent of net win

the first year and topping at five percent the third year. These tribes do not currently have

operating casinos.

The Schwarzenegger Compacts

Thirteen new or amended compacts have been negotiated between tribes and Governor

Schwarzenegger, of which eight have been ratified by the legislature. These compacts

build on the Davis Administration compacts and contain provisions providing for greater

revenue sharing with the state, enhanced patron protections, stronger environmental,

labor and building safety provisions, and most recently a problem gambling program.

They also require agreements with local governments. These compacts are likely to be

seen as models in future compact negotiations, a possibility opposed by some tribes.

(Table 8 provides information about all tribes with tribal-state gaming compacts.)

*

According to the California Gambling Control Commission, net win is “…the difference between gaming

wins and loses before deducting costs and expenses.” (CGCC Publication 1, Feb. 16, 2005, p. 5).

22 California State Library, California Research Bureau

• In January 2004, the governor successfully entered into negotiations with nine

tribes; six were parties to the 1999 tribal-state compact and sought to offer more

gaming devices, and three sought to enter into compacts for the first time. One of

the new compacts, with the Lytton Rancheria of California, was not ratified by the

legislature due to controversy over its proposed location and size. The other new

and amended compacts were ratified, resulting in a total of 66 tribes with tribal-

state gaming compacts in California (four of those tribes do not have casinos).

• In 2005, the governor negotiated four compacts (one amended, three new) that

have not yet been ratified by the legislature. Compacts with the Yurok, Quechan,

Big Lagoon Rancheria and Los Coyotes Band tribes were opposed by “smaller,

powerful tribes with big casinos” who do not support some of the new provisions

in the compacts, according to press accounts.

53

Table 3

California Indian Tribes With Unratified Compacts, October 2005

Tribe, Location, #

Members reported

to BIA (2001)

Business

Partners

State Compact

Proposed

casino

location

Number and

Types of

Games

Payments to state

and local

jurisdictions

Big Lagoon

Rancheria,

Humboldt Co., 18

members

BarWest

Gaming LLC

(Detroit)

Negotiated in

2005, land not in

trust

Barstow

Up to 2,250 slot

machines, card

games

Would pay state

16-25% annual net

win

Los Coyotes Band

of Cahuilla and

Cupeño Indians,

San Diego, 286

members

BarWest

Gaming LLC

(Detroit)

Negotiated in

2005, land not in

trust

Barstow

Up to 2,250 slot

machines, card

games

Would pay state

16-25% annual net

win

Lytton Rancheria of

California,* 246

members

Rumsey and

Pala tribes, G.

Maloof

Negotiated in

2004

San Pablo

Compact would

allow 2,500

gaming devices;

tribe has 800

class II games

and card room;

Compact provides

25% net win to

state minus local

payments; city

earned $9 million

in FY 05-06 (7.5%

revenues) from

class II games

Quechan Indian

Nation, Imperial

County, 2,668

members in Ca.

Amended 1999

compact

negotiated in 2005

Imperial

County

One casino, up

to 1,100 slots,

card games

10% net win up to

25% based on

tribal enrollment

and revenues

Yurok Tribe of the

Yurok Reservation,

Klamath, 4,466

members

Negotiated in

2005

Klamath

Up to 350

gaming devices,

card games

Sliding scale

beginning with

10% net win, up to

25%

* The Lytton Rancheria makes per capita payments to its members that total 49% of revenues. Payments to the city

of San Pablo amount to over half the city’s annual budget.

Source: California Research Bureau, California State Library, 2006.

California State Library, California Research Bureau 23

The casinos proposed in the Los Coyotes and Big Lagoon tribal-state compacts would be

located in Barstow, where neither tribe has federal trust land. The tribes would have to

secure federal and state approval and demonstrate local community support in order to

gain federal trust land for gambling purposes, a long and uncertain process.

The Quechan tribe has sued the state in federal court alleging bad-faith by virtue of the

Legislature’s failure to ratify the negotiated compact amendment, requesting that a

mediator be empowered to choose the “last best offer” as a compact binding between the

tribe and the state. If successful, this suit could obviate legislative ratification of the

amended compact.

54

The tribe wants to build a larger facility with up to 1,100 slot

machines in a better location than its existing casino. According to court filings

submitted by the tribe, 67 percent of its members are unemployed.

55

The new and amended 2004-05 tribal state compacts strengthen Indian gaming

exclusivity and in some cases allow more than 2,000 gaming devices per casino. Gaming

devices are defined to include instant lottery game devices and video poker as well as slot

machines, expanding the range of games that can be offered.

Tribal parties to the 2004 amended compacts agreed to fund a $1 billion state

transportation bond and share revenues with the state. These tribes make payments into

three accounts: the Revenue Sharing Trust Fund, the state General Fund (based on the

number of slot machines added since the amended compacts took effect), and a

transportation bond fund.

56

All the recent compacts contain increased revenue sharing provisions with the state from

ten to 25 percent of annual net win. However, the definition of annual net win is

different from that typically used by the gaming industry and in the 1999 compacts. It

allows deduction of limited operational expenses, including leasing fees for gaming

devices, thereby decreasing the revenue base on which payments to the state are

calculated. As of September 2005, $20 million had been contributed to the state’s

General Fund.

Unlike the 1999 compacts, the Schwarzenegger compacts require tribes to reach

Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) with local governments. The MOUs are to

address local land use, environmental and public safety issues, as well as mitigate local

impacts, such as increased traffic, that require infrastructure investments and increased

police and fire services. These MOUs are enforceable in state superior court under a

limited waiver of sovereign immunity.

The Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians recently agreed to pay San Diego County more

than $1.2 million for road improvements to address impacts of a planned $18 million

casino expansion, the first agreement reached in the county under the compacts

negotiated by Governor Schwarzenegger. The tribe’s expanded casino will have 2,500

slot machines, 68 table games, a 900-seat bingo hall and off-track betting. In addition,

the neighboring Ewiiaapaayp Band plans to develop a second casino on Viejas land,

24 California State Library, California Research Bureau

pending federal approval, a plan endorsed by county supervisors as a means of