The report of Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of

Education, Children’s Services and Skills 2013/14

West Midlands regional report

2

West Midlands regional report 2013/14

Evesham

Stratford

upon Avon

Great

Malvern

Hereford

Warwick

Oswestry

Uttoxeter

Worcester

Shrewsbury

Telford

Stafford

Kidderminster

Rugby

Burton upon

Trent

Tamworth

Solihull

Coventry

Sandwell

Dudley

Telford

and Wrekin

Birmingham

Worcestershire

Warwickshire

Shropshire

Staffordshire

Herefordshire

Walsall

Wolverhampton

Stoke-on-Trent

West Midlands regional report 2013/14

3

www.ofsted.gov.uk

West Midlands regional report

Summary

The proportion of good or outstanding primary schools in the West Midlands

continued to increase in the 2013/14 academic year. As in previous years,

improvement in some local authority areas has been substantial. Almost eight

out of 10 children in the West Midlands attend a primary school that is good

or outstanding. Despite this improvement, almost 100,000 primary aged

children attend schools that are less than good.

The West Midlands performs broadly in line with England as a whole at

secondary level, with 70% of schools judged good or outstanding compared

with 71% of schools nationally. However, performance in secondary schools

is inconsistent across the region. This indicates that the chance of a child

attending a good school often depends on the local authority area in which

they live.

More than three quarters of children live in a local authority area where

safeguarding arrangements are less than good and more than a third of

children live in a local authority area where safeguarding arangements are

inadequate. More work to improve the performance of local authorities

is crucial to ensure that all children in the West Midlands are safeguarded

effectively and receive the care they deserve.

One in four children’s homes in the West Midlands are not yet good.

This weak provision is leaving too many children unprotected and unable

to achieve well. Urgent and targeted action must continue and increase in

this area to secure better services for children.

There has been a marked improvement in the performance of further

education colleges in the West Midlands, with 74% of colleges now good or

outstanding. Despite this improving picture, 12 colleges are still not good

enough. There is therefore no room for complacency.

4

West Midlands regional report 2013/14

The potential for the radicalisation of pupils and the narrowing of the

curriculum remain key areas of concern, particularly for Birmingham schools.

The ineffective governance and leadership that have been observed in a

number of schools may lead to the disassociation of pupils from the wider

community. Any such disassociation must be challenged and reformed

through our work.

This report advocates Ofsted’s continued work in the West Midlands by:

extending support and challenge for schools, headteachers and governors

developing further support and challenge work with local authorities

extending the work in further education and skills to include more robust

challenge to governing bodies, to rectify key issues in teaching, learning

and assessment

seeking greater engagement from local enterprise partnerships (LEPs) in

supporting providers to model their provision so that it meets local needs

more precisely

in social care, supporting and challenging the leadership capacity of

the sector.

5

www.ofsted.gov.uk

West Midlands regional report

1.

Local authority interactive tool

, Department for Education; www.gov.uk/government/publications/local-authority-interactive-tool-lait. All attainment and

progress data is provisional data for 2014 unless otherwise specified.

State of the region

1. The proportion of primary school children now in

good or outstanding schools has improved since

2012/13 in a number of local authorities. These

improvements have been particularly marked in

Herefordshire, Dudley, Wolverhampton, Coventry

and Walsall, although Walsall and Wolverhampton

remain low in the overall rankings of local

authorities (see Table 1). However, children in

the West Midlands still have a lower chance of

attending a good or outstanding primary school

than in most other parts of England. Almost

100,000 primary-aged children do not yet attend a

good or outstanding school.

2. The proportion of good or outstanding secondary

schools is lower than the proportion for primary

schools, although it is in line with secondary schools

nationally. Only five of the local authorities have

shown improvement in this phase. In Worcestershire,

Warwickshire, Staffordshire, Shropshire and Stoke-

on-Trent, over 110,000 students now attend good

or outstanding schools – 6,000 more than last year.

In the case of Stoke-on-Trent, this improvement has

been from a very low base and the ranking of this

local authority remains low. In Sandwell and Dudley,

the ranking of secondary schools is very much lower

than that of primary schools. The quality of the

school or academy a pupil attends is still in many

cases a matter of chance.

3. Across the range of attainment measures shown

in Figure 2, the West Midlands is slightly below

national levels.

1

Just over three quarters of children

in the West Midlands achieved the expected level

of attainment in reading, writing and mathematics

at the end of Key Stage 2. Just over half (54.2%)

of pupils achieve at least five good GCSEs including

English and mathematics. However, there is too

much variation between local authorities when

considering the range of measures. Solihull performs

particularly well compared with its neighbours. Pupils

in Sandwell, Walsall, Wolverhampton and Stoke-on-

Trent perform much less well than their peers in other

local authorities in the region and nationally.

4. In 2012/13, half of the 14 local authorities in the

West Midlands were in the bottom 25% of all local

authority areas nationally for the proportion of

pupils achieving expected levels in reading writing

and mathematics at Key Stage 2. However, in

2013/14 things look more promising. Only two

local authorities in the West Midlands, Birmingham

and Walsall, remain in this bottom 25%.

Table 1: Percentage of primary and secondary pupils attending good or outstanding schools by

local authority in the West Midlands

* Rank refers to the 2014 placing in relation to all 150 local authorities in England (excluding Isles of Scilly and City of London, which each contain only one school).

Primary schools Secondary schools

Rank* Local authority (education)

2014

%

Change

from 2013

(%points)

Rank* Local authority (education)

2014

%

Change

from 2013

(%points)

24= Worcestershire 89

6 26= Telford and Wrekin 89 0

60= Solihull 84

1 46= Worcestershire 83 2

60= Dudley 84

12 46= Herefordshire 83 -6

68= Herefordshire 83

11 59= Solihull 80 0

74= Sandwell 82

0 59= Warwickshire 80 10

79= Shropshire 81

7 77= Shropshire 75 1

79= Telford and Wrekin 81

7 88= Birmingham 73 -5

91= Birmingham 80

1 92= Staffordshire 72 4

103= Warwickshire 78

5 109= Wolverhampton 67 -4

107= Staffordshire 77

6 111= Coventry 66 -22

119= Coventry 74

10 123= Walsall 57 -20

141= Walsall 68

8 127= Dudley 55 0

141= Stoke-on-Trent 68

-3 132= Sandwell 53 -21

141= Wolverhampton 68

11 134= Stoke-on-Trent 52 18

6

West Midlands regional report 2013/14

Schools

5. Since 2012/13, there has been a small increase in

the proportion of primary schools where overall

effectiveness has improved and is now good or

outstanding. In contrast, the proportion of good

or outstanding secondary schools has declined

slightly, although it is still in line with the national

figure. This means that over 28,000 more primary

aged children attend a good or outstanding school

than last year. The focus on schools that require

improvement has seen 63% of schools that were

judged to require improvement last year judged

‘good’ when re-inspected this year. Senior school

leaders, governors and local authority officers have

welcomed improvement seminars and a range of

specific workshops led by Her Majesty’s Inspectors

(HMI). Ofsted’s West Midlands regional plan for

2014/15 targets local authorities where the number

of good or outstanding secondary schools is

too low.

6. The inspection of Walsall’s local authority school

improvement services highlighted a number of

concerns. The local authority does not know its

schools well enough and it does not act quickly

enough to challenge weak leadership and effect

improvement.

7. Senior HMI in the region meet regularly with

local authority officers, providing challenge

based on analysis of performance data and local

knowledge. The focused inspections of schools in

Wolverhampton and Staffordshire identified key

weaknesses in the capacity of these authorities to

monitor school performance effectively and identify

and support their failing schools. As part of the

first focused inspections of a multi-academy trust,

Ofsted inspected six E-ACT academies in the West

Midlands. These inspections highlighted the urgent

need for E-ACT to improve the quality of teaching

in its schools.

8. The number of academies in the West Midlands

has grown rapidly in recent years (see Table 2). By

August 2014, just over one in five of all schools in

the region were academies (21% of schools). This is

broadly in line with the proportion of academies

nationally, which stands at 20% of all schools.

At a local level, the extent of academisation varies

considerably across local authority areas, from just

9% of all schools in Dudley to 39% of schools in

Stoke-on-Trent.

Table 2: Number of primary and secondary schools that are academies in the West Midlands

Year 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14

Number of primary academies 0 18

61

170 245

Number of secondary academies 23 102 165 214 243

7

www.ofsted.gov.uk

Explore inspection data directly at dataview.ofsted.gov.uk. Data View is a digital tool that allows Ofsted inspection data to be viewed in a simple and visual

way. You can compare and contrast performance in inspections between regions, local authorities and parliamentary constituencies across all remits that Ofsted

inspects.

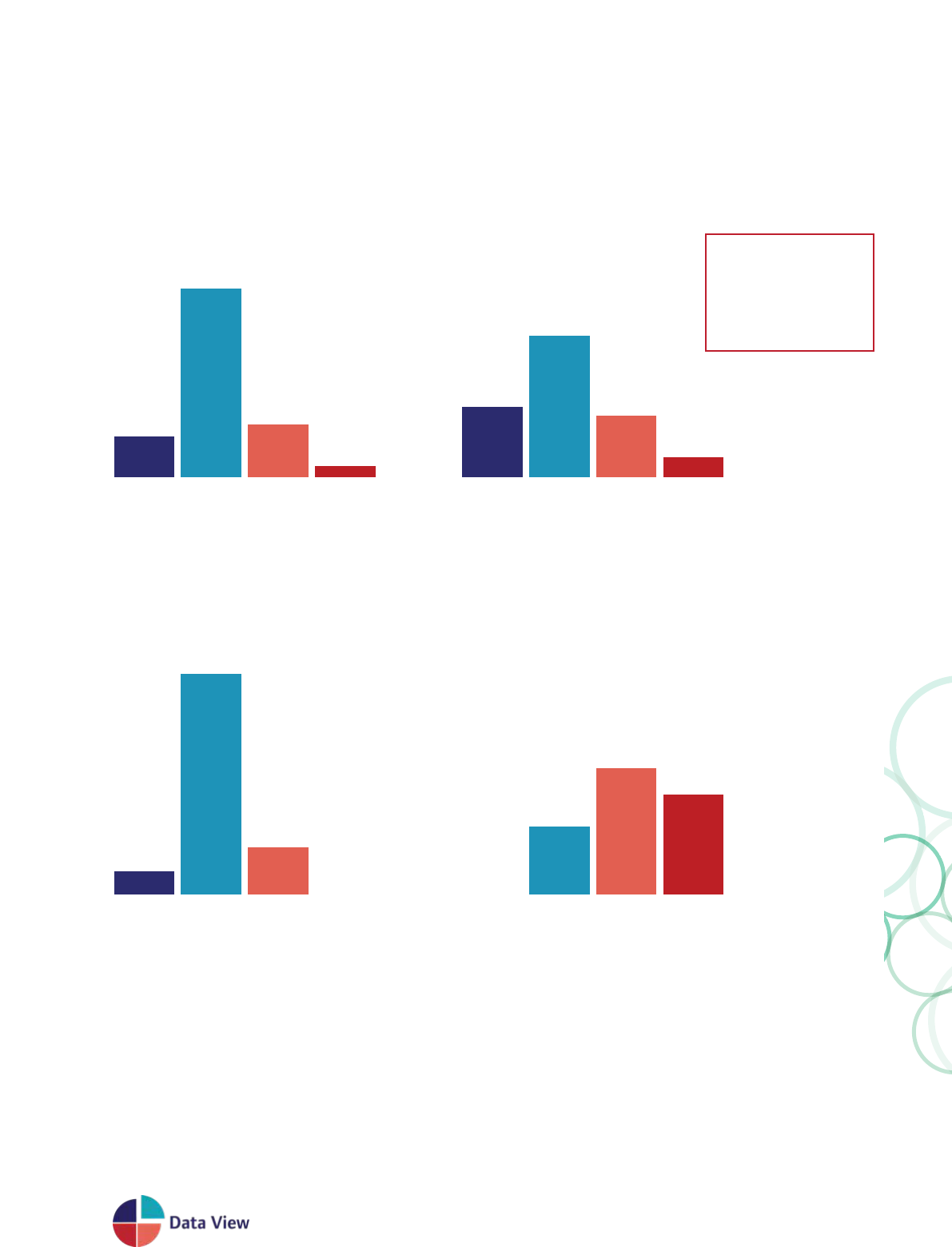

Figure 1: Inspection outcomes by proportion of pupils, children or

learners at 31 August 2014

Overall effectiveness of primary schools in the

West Midlands, latest inspection outcome at

31 August 2014 (% of pupils).

Overall effectiveness of colleges in the

West Midlands, latest inspection outcome

at 31 August 2014 (% of learners).

Overall effectiveness of secondary schools in

the West Midlands, latest inspection outcome

at 31 August 2014 (% of pupils).

Effectiveness of local authority safeguarding

arrangements, last inspection outcome at

31 August 2014 (%).

Primary schools

Colleges

Secondary schools

Safeguarding

West Midlands regional report

Inadequate

Requires Improvement

Good

Outstanding

Primary Schools

4%

18%

64%

14%

Inadequate

Requires Improvement

Good

Outstanding

Colleges

0%

16 %

75%

8%

Inadequate

Requires Improvement

Good

Outstanding

Secondary Schools

7%

21%

48%

24%

Inadequate

Requires Improvement

Good

Outstanding

Safeguarding

34%

43%

23%

0%

Inadequate

Requires improvement

Good

Outstanding

Primary Schools

1%

15%

64%

20%

8

West Midlands regional report 2013/14

Figure 2: Pupil attainment at ages five, seven, 11 and 16

Data for 2014 is provisional

Benchmark levels: Early Years Foundation Stage – achieving a good level of development (%)

Key Stage 1 – achieving at least Level 2 in reading (%)

Key Stage 2 – achieving at least Level 4 in reading, writing and mathematics (%)

Key Stage 4 – achieving at least five GCSEs at grades A* to C or equivalent, including English and mathematics (%)

All attainment and progress data are provisional data for 2013/14 unless otherwise specified.

Source:

Local authority interactive tool,

Department for Education; www.gov.uk/government/publications/local-authority-interactive-tool-lait.

Explore how children and young people performed in assessments and tests at different ages and in different

regions through our online regional performance tool; http://dataview.ofsted.gov.uk/regional-performance

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Key Stage 4Key Stage 2Key Stage 1 readingEarly Years Foundation Stage

Chart 3: Pupil attainment at ages 5, 7, 11, 16 and 19

EnglandWest Midlands

2012/13 England

2012/13 West Midlands

58

60

89

90

76

78

54.2

56.1

2.

Advice note provided on academies and maintained schools in Birmingham to the Secretary of State for Education, Rt Hon Michael Gove MP, as commissioned

by letter dated 27 March 2014,

Ofsted, June 2014; www.ofsted.gov.uk/resources/advice-note-provided-academies-and-maintained-schools-birmingham-

secretary-of-state-for-education-rt.

9. HMI carried out inspections of 21 schools in

Birmingham between March and May 2014. Fifteen

of these schools were inspected at the request of

the Secretary of State. Six were inspected because

of Ofsted’s concerns about the effectiveness of

safeguarding and leadership and management in

these schools. Following the inspections, Ofsted

published an advice note to the Secretary of State.

2

The evidence shows that:

‘…governors have recently exerted inappropriate

influence on policy and the day-to-day running

of several schools in Birmingham. In other schools,

leaders have struggled to resist attempts by

governing bodies to use their powers to change

the school in line with governors’ personal views.

Birmingham City Council has failed to support a

number of schools in their efforts to keep pupils

safe from the potential risks of radicalisation

and extremism. It has not dealt adequately with

complaints from headteachers about the conduct

of governors. Her Majesty’s Inspectors identified

breaches of funding agreements in a number of

academies. In several of the schools inspected,

children are being badly prepared for life in modern

Britain.’

West Midlands regional report

9

www.ofsted.gov.uk

10. The inspections have created a high-profile agenda for change and

have resulted in Ofsted reviewing the way it inspects the curriculum.

The issues identified in Birmingham remain a significant concern. These

inspections have called into question the nature and extent of the

accountabilities associated with the high levels of autonomy currently

enjoyed by academies. They also raise concerns about the effectiveness

of the local authority to hold schools and governing bodies to account.

11. HMI lead training on evaluating school performance and work alongside

senior school leaders and governors as they take a critical view of their

own schools. Much of this work has taken place in south Birmingham

and Herefordshire, which has increased management capacity in schools

and in the respective local authorities.

12. Given its precarious position in both the regional and national tables,

Stoke-on-Trent has been a major focus of HMI attention over the

past 12 months. HMI wanted to know why educational outcomes in

Stoke-on-Trent have been so poor for so long. Consequently, they

undertook a series of forensic inspection activities designed to get to the

bottom of what is going wrong in schools in this authority. They applied

a fourfold approach to promote improvement. This included a focus on:

the teaching of reading in primary schools

reading and literacy in secondary schools

mathematics in secondary schools

developing subject-specific and leadership capacity within schools

and across the local authority.

The findings have been shared with schools and the local authority to

aid improvement.

Initial teacher education

13. All initial teacher education (ITE) provision in the West Midlands is

good or outstanding.

3

The region is well served, with substantial higher

education providers of ITE. New school-centred initial teacher training

(SCITT) partnerships are proliferating in the centre and north

of the region.

3. The requires improvement provider listed in statistics about the inspection outcomes of ITE providers at 31 August 2014 has since closed.

10

West Midlands regional report 2013/14

Further education and skills

14. In Ofsted’s 2012/13 West Midlands regional report, the poor

performance of further education colleges was a key headline. Only

51% of colleges in the region were good or outstanding and the region

had the highest proportion of inadequate colleges in the country. The

approach of HMI to tackling poor performance started with supporting

and challenging colleges to improve through a programme of individual

improvement visits and an extensive seminar programme for college

managers and governors. This seminar programme was based on

common areas for improvement identified through rigorous analysis

of inspection reports and performance data. In addition, extensive

networking with the sector through stakeholder groups such as the

Association of Colleges has helped to communicate and share the key

messages and commitment to improve. This work has contributed to

notable improvements in inspection grades, as confirmed by feedback

from providers. At the end of 2013/14, 74% of colleges are good or

outstanding, and none of the colleges are inadequate.

15. In independent learning and community learning and skills providers,

performance has remained strong. Most providers (82%) were judged

good or outstanding at their most recent inspection. Of the 19 providers

inspected in 2013/14, 12 were judged good for overall effectiveness.

Six of these providers improved to good; five of these benefited from

direct support and challenge work with HMI.

16. In spite of the notable improvement in college inspection grades,

12 colleges were judged as requires improvement for overall

effectiveness at their most recent inspection. Inspection reports and

letters from support and challenge work with providers that require

improvement give a number of key messages. Where providers have

not improved quickly enough, several factors have contributed to this.

In a few cases, providers have taken well-conceived action to improve.

Unfortunately, this has not had a consistent impact across the range of

their work but rather has resulted in insufficient progress in improving

teaching, learning and assessment or outcomes for learners. In these

cases, quality assurance monitoring is not consistently rigorous in

rooting out the causes of continuing weaker performance and resulting

actions are not as sharply focused as they need to be. In other providers

where progress has been slow, boards of governors or trustees do

not always have the information they need to be able to hold senior

leaders to account for the quality of teaching, learning and assessment

or the performance of learners; they do not know what the gaps in

their information and data are. In other cases, governors do not have

the appropriate skills and expertise to enable them to fulfil their roles

appropriately and governing bodies have not evolved to match the

changing needs of the provider.

West Midlands regional report

11

www.ofsted.gov.uk

17. In smaller providers, inspectors raise questions about the capacity of the

provider to improve. Leaders and managers struggle to find the time to

step back from day-to-day problem-solving to seek out and act on the

issues that are holding them back from improving the provision.

18. In teaching, learning and assessment, the main area for improvement

continues to be teachers not planning well enough to challenge all

learners to improve based on their prior skills and learning. Teachers do

not make enough use of targeted assessment in learning activities to

be able to measure individuals’ learning and progress with sufficient

precision. In work-based learning, challenges for providers persist

around the coordination of on- and off-the-job learning, resulting too

often in learners making slow progress.

19. The influence of LEPs is growing. However, further education is still

under-represented on LEP boards in the West Midlands. Providers

that have re-modelled their offer based on local employment needs

are getting little practical support from LEPs. This is because LEPs’

strategic priorities are broad and do not focus sufficiently on learners

who need provision below advanced level as a first step. They have little

focus on learners who are not in employment, education or training

or who have left school with fewer than five GCSEs at grades A* to C

including English and mathematics. They have been slow to reinforce

the messages from the introduction of 16 to 19 study programmes.

These include improving the availability and quality of work experience

for learners and raising standards in learners’ English and mathematics

skills to enable a smoother transition into employment. These aspects of

study programmes are significant areas for development for the further

education sector overall.

Social care

20. More than three quarters of children in the West Midlands live in a local

authority area where safeguarding arrangements are less than good

and one in every three where they are inadequate. This performance

is unacceptable and a significant number of children and young

people are not receiving the good services they require to be well

protected and cared for. Most local authorities require improvement.

In recent inspections, Coventry and Birmingham were both judged

to be inadequate. Recent successes can be seen in improvements

in Staffordshire where provision is now good. In Herefordshire the

provision is no longer inadequate but still requires improvement.

12

West Midlands regional report 2013/14

4.

Report into allegations concerning Birmingham schools arising from the ‘Trojan Horse’ letter,

July 2014; www.gov.uk/government/publications/birmingham-

schools-education-commissioners-report.

5. Independent review into corporate governance at Birmingham City Council, Department for Communities and Local Government, due to publish December 2014;

www.gov.uk/government/news/independent-review-into-corporate-governance-at-birmingham-city-council.

21. The West Midlands region has the second largest number of children’s

homes in the country, offering approximately 1,260 places, yet more

than one quarter of homes are not yet good. This means that there are

approximately 500 places available for children in provision that has

not yet met the required standard. Since February 2014, we have taken

action to close three children’s homes. Helping to improve services for

children and young people who need help, protection and care is our

highest priority and we are doing this through providing challenge and

support to local authority senior managers and their staff.

22. Educational outcomes for looked after children and care leavers at Key

Stages 1 and 2 are merely in line with national levels. At Key Stage 4

they are just above the national level.

23. Ofsted will be publishing its Social Care Annual Report in spring 2015.

This will set out the challenges for the sector and the priorities for

improvement. For this reason we have not looked at the social care

issues for the region in any detail in this report.

Regional priorities

Schools

24. Birmingham will remain a focus of our work in the region. Ofsted has

created an additional Senior HMI role in the region to enable a more

urgent and sustained focus on Birmingham schools. HMI will work

closely with the local authority to ensure that the single integrated

plan, developed following the recent Ofsted, Clarke and Kershaw

reports, delivers better outcomes and a safer learning environment for

Birmingham pupils.

4,5

25. The success of peer-to-peer review, where headteachers develop

their knowledge, skills and understanding of effective self-evaluation,

indicates that this strategy should be extended to all local authority

areas. This work has increased management capacity in schools and

in the respective local authorities, giving confidence that leaders and

managers have the skills and experience to improve the provision.

West Midlands regional report

13

www.ofsted.gov.uk

26. Ofsted has put plans in place to extend existing training and support

for schools. The programme of ‘Getting to good’ seminars, which has

proved so successful and has been welcomed by the sector, will provide

the foundation for more focused improvement workshops. This will

encompass specific themes or subjects identified through the scrutiny

of inspection reports, by the ongoing scrutiny of performance data, or

by local knowledge of schools’ needs. We will deliver training to support

school leaders at all levels to drill down into their data to gain a better

understanding of how to improve school performance. Specific work

with headteachers will enable senior leaders to gain a better grasp of

self-evaluation. We will continue to work alongside particular local

authorities in support and challenge.

Further education and skills

27. The strategies adopted to date in further education and skills have

proved very successful but have not eliminated provision that requires

improvement. Individual visits to providers that focus specifically on

the provider’s key development areas from their most recent inspection

have been collaborative and challenging. A regional seminar programme

began in earnest in September 2013, with themes common to providers

across the region. We will continue these throughout 2014/15 and

will develop seminars already delivered on aspects such as improving

the provision of English and mathematics and integrating the use

of information learning technologies into teaching, learning and

assessment.

28. For the remaining requires improvement provision to move to good,

providers need to ensure that self-assessment and quality assurance are

ruthless in rooting out the causes of continuing weakness. Providers

must ensure that resulting action plans are fit for purpose in setting

targets that allow them to make progress and establish the impact of

actions. Governors need to identify what they do not currently know,

ensuring that the information they receive enables them to take a

forensic overview of the quality of teaching, learning and assessment

and its impact on outcomes for learners. They need to ensure that they

hold senior management fully to account for the quality of provision.

29. In teaching, learning and assessment, teachers need be supported

to plan learning that ensures that all learners make progress in their

learning according to their potential. Initial and diagnostic assessment

and prior attainment information they receive on learners are often

excellent, but teachers too often fail to make sufficient use of these.

Weaknesses in the use of targeted assessment mean that teachers do

not always know very clearly what progress their learners are making.

In work-based learning, on- and off-the-job learning is still not

coordinated well enough in too many cases, so that learners do not

make the progress they are capable of.

14

West Midlands regional report 2013/14

30. All LEPs need to ensure that further education is represented on

their main board, so that they are not being held ‘at arm’s length’.

They need to concentrate more on provision below advanced level

for those learners who are not in education, employment or training

or who have left school with fewer than five GCSEs at grades A* to

C including English and mathematics. LEPs need to engage with the

further education sector to help it model provision more closely to local

employment needs and to work with employers to make available a

range of high-quality work experience and apprenticeship opportunities.

Social care

31. Helping to improve services for children and young people who need

help, protection and care is our highest priority. We are doing this

through providing challenge and support to local authority senior

managers and their staff. Currently, too many social worker posts

are vacant and too many poor quality managers move between local

authorities without being challenged or supported to improve their

professional practice. This has a significant impact on the quality of

the children’s services workforce in the region. Through inspection,

our improvement role and work with the West Midlands Association

of Children’s Services, we will continue to offer support and challenge

and broker information-sharing regarding good practice. We continue

to challenge the sector to raise standards through ensuring that

appropriate and targeted regulatory action is taken when providers fail

to meet the standards required for children and young people who are in

care provision.

The Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) regulates and inspects

to achieve excellence in the care of children and young people, and in education and skills for learners

of all ages. It regulates and inspects childcare and children’s social care, and inspects the Children and

Family Court Advisory Support Service (Cafcass), schools, colleges, initial teacher training, work-based

learning and skills training, adult and community learning, and education and training in prisons and other

secure establishments. It assesses council children’s services, and inspects services for looked after children,

safeguarding and child protection.

If you would like a copy of this document in a different format, such as large print or Braille, please

telephone 0300 123 1231, or email [email protected].uk.

You may reuse this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium,

under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit

www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/, write to the Information Policy Team,

The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected].uk.

This publication is available at www.ofsted.gov.uk/resources/140189.

To receive regular email alerts about new publications, including survey reports and school inspection

reports, please visit our website and go to ‘Subscribe’.

Piccadilly Gate

Store Street

Manchester

M1 2WD

T: 0300 123 1231

Textphone: 0161 618 8524

E: enquiries@ofsted.gov.uk

W: www.ofsted.gov.uk

No. 140189

© Crown copyright 2014