Revue de la culture matérielle 88-89 (Automne 2018-Printemps 2019) 1

Articles

Articles

GABRIEL SILVA COLLINS AND ANTONIA E. FOIAS

Maize Goddesses and Aztec Gender Dynamics

Abstract

This article provides new evidence for understanding

Aztec religion and worldviews as multivalent rather

than misogynistic by analyzing an Aztec statue of

a female deity (Worcester Art Museum, accession

no. 1957.143). It modifies examination strategies

employed by H. B. Nicholson amongst comparable

statues, and in doing so argues for the statue’s

identification as a specific member of a fertility

deity complex—most likely Xilonen, the Goddess

of Young Maize. The statue’s feminine nature does

not diminish its relative importance in the Aztec

pantheon, but instead its appearance and the depicted

deity’s accompanying historical rituals suggest its

valued position in Aztec life. As documented by

Alan R. Sandstrom and Molly H. Bassett, modern

Nahua rituals and beliefs concerning maize and

fertility goddesses add to the conclusions drawn from

the studied statue and suggest that historical Aztec

religion had a complementary gender dynamic.

Résumé

Cet article expose de nouvelles données pour

comprendre la religion des Aztèques et leur vision

du monde sous un angle polyvalent plutôt que

misogyne, en analysant la statue d’une divinité

féminine (conservée au musée des beaux-arts de

Worcester, sous la référence no1957.143). Il modifie

les procédés d’examen qu’employait H.B.Nicholson

pour des statues comparables, et ce faisant, argumente

que la divinité que représente cette statue peut être

identifiée à un membre particulier d’un complexe de

divinités de la fertilité – il s’agit plus particulièrement

de Xilonen, la déesse du jeune maïs. La nature

féminine de la statue n’amoindrit pas son importance

relative dans le panthéon aztèque; au contraire, son

apparence et la description historique des rituels

consacrés à cette divinité indiquent qu’elle occupait

une position privilégiée dans la vie des Aztèques.

Ainsi que le documentent Alan R. Sandstrom et

Molly H. Bassett, les rituels et les croyances modernes

des Nahuas entourant les déesses du maïs et de la

fertilité s’ajoutent aux conclusions tirées de l’étude

de la statue et indiquent que la religion historique

des Aztèques possédait une dynamique des genres

complémentaires.

2 Material Culture Review 88-89 (Fall 2018-Spring 2019)

Corn is our blood. How can we grab [our

living] from the earth when it is our own

blood that we are eating?

(Aurelio qtd. in Sandstrom 1991: 240)

By the early 15th century, a diverse sculptural

tradition was expressed in Aztec (or Mexica)

art, including tiny figurines, exquisitely carved

animals of every shape and size, and monolithic

statues of deities. Although some scholars have

stressed gender complementarity in Aztec art

and religion (McCafferty and McCafferty 1988,

1999; Sigal 2011), others have argued that Mexica

ideology and sculptural art were misogynistic

(Klein 1988, 1993, 1994; Clendinnen 1991;

Nash 1978, 1980). The latter narrative stresses

male (warrior) dominance over women, seem-

ingly celebrated in the legend of the Aztec

patron god of war Huitzilopochtli sacrificing his

sister Coyolxauhqui. A circular stone carving of

Coyolxauhqui’s desmembered body was found

at the base of the Great Temple at Tenochtitlán,

the Aztec capital (Joyce 2000: 165-66; see

also Brumfiel 1991, 1996). Scholars such as

Joyce (2000), Brumfiel (1991, 1996), Dodds

Pennock (2008, 2018), Kellogg (1995), and the

McCafferties (1988, 1999) have been vocal crit-

ics of this interpretation. Here we bolster their

critique by focusing on pre-Columbian Aztec

female maize deities and their continuing impor-

tance among modern Mesoamerican Indigenous

populations. Contemporary rituals and Aurelio’s

words that “Corn is our blood” further testify to

the enduring centrality of corn (both male and

female) to Indigenous identity in Mexico and

Central America.

In an early study of maize/fertility goddesses,

Nicholson noted that “more [stone Aztec images]

probably represent the fertility goddess than any

other single supernatural in the pantheon” (1963:

9; Pasztory 1983: 218). The high frequency of

these stone effigies of fertility goddesses suggests

that they were held in high esteem by much of

the empire’s population. Furthermore, in contrast

to many Mesoamerican civilizations (such as the

Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, and Toltec) all of which

had a male maize god, the Aztecs viewed their

maize deities as both female and male, undermin-

ing an entirely misogynistic interpretation of

Aztec religion. In this article, we analyze an Aztec

fertility goddess sculpture in the Worcester Art

Museum (accession no. 1957.143), and present

new interpretations about its identificaton as

the young maize goddess Xilonen within the

larger cluster of male and female maize deities

that remain at the heart of many Indigenous

Mesoamerican religions today. We argue that

the Worcester Art Museum statue and the many

others representing maize goddesses suggest that

Aztec worldviews were multivalent rather than

simply misogynistic.

The Worcester Art Museum (WAM) Aztec

sculpture (accession no. 1957.143) is carved

from a solid piece of gray volcanic stone. It is

almost completely covered by a red pigment,

probably specular hematite.

1

This seated female

looks directly forward, wearing a triangular

quechquemitl shawl and garment that extends to

her shins. The statue’s large hands are positioned

over her crossed legs. The statue is also carved on

the sides with continuations of features found on

the front, but its back is unmarked (Figs. 1a, b, c).

The statue’s most elaborate part is the head

and headdress. This is not surprising, since

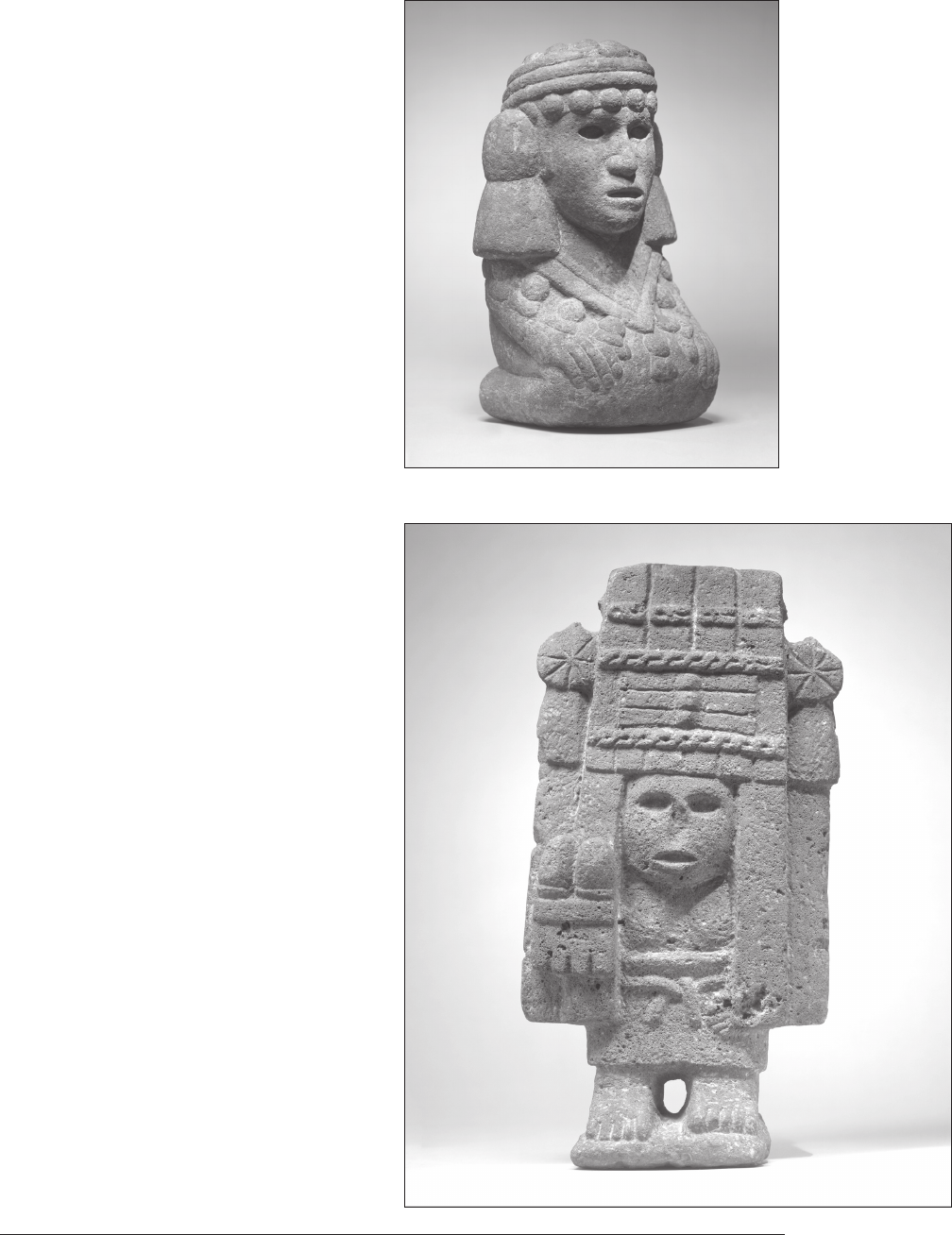

Figs. 1a, b, c (opposite)

The Worcester Art

Museum’s Fertility

Goddess, 1450-1521,

accession no. 1957.143

©Worcester Art

Museum, Massachusetts.

Revue de la culture matérielle 88-89 (Automne 2018-Printemps 2019) 3

one of the vital life forces described by modern

Nahua peoples (descendants of the Aztecs)—the

tonalli—is concentrated in the head. Several

prominent features adorn her head, including

two large circular earspools, a headband consist-

ing of five flowers, and a headdress with two

maize cobs and a central feather ornament (to

be detailed further below). Two vertical black

bars are painted on each cheek. She also wears a

double-strand necklace, with large spherical and

tubular beads and a central trapezoidal ornament.

While the lower half of the statue is engraved

carefully to depict all fingers, toes, and their

nails, the most powerful details are centered

on the face and surrounding adornments. The

highly naturalistic visage is carved in deeper relief

than any other part of the sculpture. The artist’s

focus on the head suggests that the head and

surrounding features were carved as the deity’s

identifying insignia. The exaggerated size of the

head and headdress in relation to the rest of the

statue’s body further suggests these parts of the

sculpture are the most important areas.

Animacy, Divinity and Embodiment

among the Aztecs and Nahua

One of the most important categories of Mexica

art were god effigies, like the WAM statue, called

teixiptlahuan (singular teixiptla in Nahuatl, the

Aztec language). These effigies were considered

localized embodiments of deities and divine pow-

er that were essential to religious performances

and worship (Bassett 2015). Stone teixiptlahuan

have been documented as corporeal forms of

divine beings or forces, and provide a direct

window into the expression of pre-Hispanic

Mesoamerican religion. Rather than seeing these

effigies as objects or representations of the gods,

the pre-Hispanic Aztecs perceived them as the

live bodies of the deities, and many Indigenous

Central American groups continue to do so today.

In other words, teixiptlahuan were the essential

actors of Aztec religion and ritual. Religious

life was centered on highly ritualized public

ceremonies, where teixiptlahuan in the form of

either costumed priests or statues became the

4 Material Culture Review 88-89 (Fall 2018-Spring 2019)

earthly manifestations of various deities (Bassett

2015: 135).

These figures combined the divine presence

in the earthly world with its justification: the view

of the whole universe as animate. According to

modern Nahua people in Veracruz, everything

in the world is animate, except perhaps certain

plants and rocks (Bassett 2015: 11-12; Sandstrom

1991). Animacy, defined by the ability to move,

exists on a spectrum from teteo (deities, singular

teotl) having the most, to wild and domesticated

animals, which have the least (Bassett 2015).

Among the teteo, Tohueyinanan (Our Great

Mother/Goddess) and Tohueyitatah (Our Great

Father/God) have the most, followed by Dios, the

Stars, the Sun (often conjoined with Jesus Christ),

and the Moon on the next level; mountains,

water, fire and wind on the third highest level;

and then macehualli (Nahuatl speakers) and

coyomeh (non-Nahuatl speakers) on the following

lower level, and wild and domestic animals on

the lowest rung (Bassett 2015: 12-13; Sandstrom

1991: 236).

Among the pre-Columbian Aztecs and their

descendants, animacy was and is predicated on a

life force which permeated everything and origi-

nated with the gods (Furst 1995; Lopez Austin

1988; Townsend 2009). The life force had multiple

threads: 1) yolia: the life force in the heart; 2)

tonalli: heat, warmth, and destiny; 3) ihiyotl: the

life force in the breath; 4) nagual: co-essence

which is most often an animal, but could also be

other natural phenomena, like thunder (Furst

1995; Lopez Austin 1988; Sandstrom 1991). Of

these life forces, tonalli is the most important for

our discussion because it refers to an individual’s

(or god’s) destiny and personality (Furst 1995;

Sandstrom 1991). An individual’s tonalli is inher-

ent in their birthday as reckoned in the 260-day

divination calendar (Bassett 2015; Furst 1995;

Lopez Austin 1988). As such, the birthday in the

260-day calendar becomes the calendrical name

of the individual or god (Townsend 2009: 127).

While details differ among Indigenous groups,

the belief in multiple life forces or vital essences

is widely spread throughout current Mexico

and Central America (Furst 1995; Gossen 1996;

Monaghan 1998; Pitarch 2010; Sandstrom 1991,

2009).

In the pre-Hispanic Central Mexican

worldview, these vital life forces emanated

from the gods (Lopez Austin 1988: 210). Such

divinely-given forces were not only essential to

humanity, but were fundamental to the entire

universe, providing basic necessities such as light

and warmth (206). Thus divine interaction with

the human world was necessary for everything

in the earthly realm, whether human, animal or

plant. For the Mexica, the divine body’s corporeal

presence in the mundane world was a means to

maintain the necessary influx of these vital life

forces for humanity and surrounding universe.

Every moment of existence in the mundane world

was a complicated relationship of influences from

divine realms, and deities were the conscious

providers of those influences (Lopez Austin 1988:

209). The essential corporeal presence of deities

on earth was achieved through the transforma-

tion of earthly objects (such as statues) or humans

(priests or sacrificial victims who “impersonated”

the gods) into actual divine bodies existing on the

human plane (Bassett 2015).

The complex nature of Mexica religion

makes identifying and describing teixiptlahuan

a difficult task. Dozens of deities were major

figures in Mexica religious life. These teteo could

also have different manifestations, changing

their aspects and roles according to cardinal

directions and days of the year. In addition, teteo

could be expressed in intricate combinations that

referenced multiple deities in a single statue or

depiction, bringing multiple aspects together into

one teixiptla. All of these possibilites for variation

in teixiptlahuan have led to debates about the

nature of divinity among the Aztecs, including

whether they were individual gods or simply

manifestations of a widespread life force energy

that defined a unified pervasive divinity (Maffie

2014). While it is beyond the scope of this article

to engage with the details of this debate, there is a

rising consensus that Nahua religion specifically,

and many Mesoamerican religions more broadly,

was pantheistic in that “the entire universe and

all of its elements partake of deity ... everybody

and everything is an aspect of a grand, single,

and overriding unity” (Sandstrom 1991: 238),

while at the same time, these groups recognized

individual deities within the larger unity (Bassett

2015; Lind 2015; Sandstrom 1991).

Revue de la culture matérielle 88-89 (Automne 2018-Printemps 2019) 5

Figs. 2a, b (below left) c, and d (below, right)

Group of Aztec statues of fertility goddesses comparable to the WAM statue: a.

Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City (no. 11.0-02997; Archivo Digital de

las Colecciones del Museo Nacional de Antropología. INAH-CANON); b. Head of

Xilonen, the Goddess of Young Maize, 1400-1500, The Art Institute of Chicago no.

1986.1091 (note two vertical bars carved on each cheek); c. Metropolitan Museum

no. 1979.206.1386; d. Metropolitan Museum no. 1979.206.407. Note also that a, c,

d are carved on the back or top of the head with the calendrical name “7 Serpent”

(Chicomecoatl).

6 Material Culture Review 88-89 (Fall 2018-Spring 2019)

Iconographic Analysis of WAM Statue

The only study of statues similar to the WAM

Aztec fertility goddess was authored by the

foremost Aztec scholar H. B. Nicholson in 1963,

where the WAM statue was not mentioned. In his

1963 article, Nicholson examined a group of six

Aztec female statues, representing fertility god-

desses and sharing many features with the WAM

sculpture. The six statues described by Nicholson

are found in museums all over the world (see, for

example, Figs. 2a, b, c, d).

2

Nicholson suggested that this group of

fertility goddess statues often blend insignia from

two Aztec deities, both important for fertility:

Chalchiutlicue and Chicomecoatl. Chalchiutlicue

(translated as “She of the Jade Skirt”) is a water

goddess of streams, rivers and lakes (Fig. 3),

while Chicomecoatl (translated as the Aztec

calendrical name “7-Serpent”; chichome, “7”

and coatl “serpent”) is the deity of mature maize

and plant growth (Fig. 4). He suggests that such

insignia sharing was due to the Aztec belief that a

divine life force pervaded everything in the world

(1963: 22). According to this view, similar features

between representations of supposedly discrete

deities reflect an Aztec theology that emphasized

a more singular, widespread divine force which

could be manifested in different individual

forms. Below we will provide a separate, more

differentiating interpretation of these common

insignia.

The group of six fertility goddess statues

described by Nicholson in 1963 all share a

“near-identity of style” (21). They are seated,

although all except the WAM statue have their

legs tucked under them. In fact, most Mexica

statues of women or female deities are shown in

this gender-specific kneeling position (Pasztory

1983; Diel 2005). The WAM piece’s excep-

tional cross-legged position is highly unusual and

unique in this group of otherwise comparable

fertility goddesses. In all well-preserved cases,

these statues have carefully carved hands resting

on the knees, a feature which appears in other

female deity statues (e.g., Fig. 3).

Adding to their similarity, all six statues and

the WAM fertility goddess are adorned with a

wreath of five to seven flower blossoms around

their foreheads, a feature rare in most Aztec fertil-

ity goddesses (Nicholson 1963: 16). However,

Fig. 3.

Stone statue of

Chalciuhtlicue, goddess

of streams, rivers and

lakes. Metropolitan

Museum of Art,

accession no. 00.5.72.

Fig. 4 (below)

Stone statue of

Chicomecoatl, goddess

of mature maize. Note

the two corn cobs held

in her right hand.

Metropolitan Museum

of Art, accession no.

00.5.51.

Revue de la culture matérielle 88-89 (Automne 2018-Printemps 2019) 7

these wreaths connect with modern Nahua beliefs

that maize deities have a female aspect called

“5-Flower” and a male aspect called “7-Flower,”

as described by Sandstrom in his ethnography

of the Nahua community of Amatlán, Veracruz.

He writes:

The corn spirit exists in both male and

female aspect. The male aspect is called

chicomexochitl (“7-flower”) and the female

aspect is macuili xochitl (“5-flower” both

terms in Nahuatl). [...] When I pressed

the villagers for more details about the

corn spirit, they replied that 7-flower and

5-flower are divine twin children with hair

the color of corn silk. (1991: 245)

Here, contemporary Nahuas’ recognition of

intertwined male- and female-deity complexes

continues similar understandings in pre-Hispanic

Mexica religion discussed later in this article.

Five statues and the WAM fertility goddess

all wear identical circular earspools decorated

with tassels that drape down over the figure’s

shoulders. Nicholson identifies the double

tassels as indicative of mixed Chalchiuhtlicue-

Chicomecoatl figures, but equally plausible is

that these earrings are symbols shared by both

the water and maize goddesses (Nicholson 1963).

All six statues as well as the WAM fertility

goddess wear a jade “necklace with a trapezoidal

pendant” (Nicholson 1963: 21). This pendant

has been interpreted as the symbol chalchihuitl,

“jade” or “precious” (11). The chalchihuitl brings

the goddess Chalchiuhtlicue to mind, whose

name literally translates to “She of the Jade Skirt.”

Nevertheless, variations of this pendant also exist

in depictions of maize goddesses (11), and may

simply symbolize how valuable and beloved all

goddesses were in Mexica worldview by being

adorned with rich jewelry that reflected value in

both name and substance (Bassett 2015: 124-25).

Durán (1971) provides another explanation for

this jade ornament: he writes that Chicomecoatl

had a second name, Chalchiuhcihuatl or “Woman

of Precious Stone” (222).

The double parallel black bands painted on

the WAM statue’s cheeks and carved on the face

of the statue in the Art Institute of Chicago (Fig.

2b), may be associated with rain (Nicholson and

Berger 1968: 11). They are reminiscent of the

parallel blue stripes found on temples dedicated

to the rain god Tlaloc, Chalchiuhtlicue’s consort

(Nicholson 1963: 13). However, they are often

associated with both water and maize goddesses,

and may indicate the wish of their sculptors for

rain to bless the fertility goddesses and/or maize

crops (12). For example, Pohl and Lyons (2010:

43) show a clay statue of a goddess decorated

with a black vertical stripe on each cheek (Fig.

5). Cheek bars are present even though the statue

Fig. 5.

Clay statue of Chicomecoatl depicted with black bands on

her cheeks. Note corn cobs in her hands, and the goddess’s

typical large paper headdress decorated with flowers or

rosettes in each corner, comparable with Fig. 4. Museo

Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico City, no. 11.0-11111;

Archivo Digital de las Colecciones del Museo Nacional de

Antropología. INAH-CANON.

8 Material Culture Review 88-89 (Fall 2018-Spring 2019)

is confidently identifiable as Chicomecoatl: the

sculpture holds two corn cobs in each hand and

wears the goddess’s typical large rectangular

amacalli headdress. Furthermore, as described

below, young girls participating in the great

spring festival honoring Chicomecoatl in

Tenochtitlán were painted with black tar on the

cheeks (Sahagún 1950-1982: Book II, 63), which

may be similar to the marks on the Worcester Art

Museum’s statue.

In spite of such possible rain-related insignia,

the group of statues that Nicholson examined

are tightly linked to maize goddesses. Three of

the statues in the group are clearly related to

the maize goddess Chicomecoatl because they

are carved with this deity’s calendrical name of

“7-Serpent” (Nicholson 1963: 21-22): two of these

have no corncobs in their headdress (Figs. 2c,

d), while the third does (Fig. 2a). The presence

of corn cobs in the headdresses of three of these

statues (for example Figs. 2a, b) as well as the

WAM goddess, also identifies them as maize

deities. The two maize cobs, and their fine tassels

that fall on the side of the goddesses’ heads as

silky hair, are known as “cemmaitl, the double

maize ear symbol, so diagnostic for the deities of

this plant” (18). Between the two ears of maize,

sits a cluster of short, medium and long plumes

identified as a quetzalmiahuayotl, or “quetzal

feather-maize tassel” (18). The quetzalmiahuayotl

is connected to fertility deities that appear in both

Aztec sculptures and codices, although the mean-

ing of this symbol is unclear: is it metaphorically

stating that tasselled corn is precious like quetzal

feathers (Nicholson 1963: 19-20)? Olko (2014:

69) has also suggested that the quetzalmiahuayotl

simply denotes and emphasizes divine identity.

The five-flower headband worn by most

of these seven Aztec female statues, including

the WAM Aztec fertility goddess, intimates one

more association with a third pre-Columbian

deity: Macuilxochitl (macuil, “Five” and xochitl,

“Flower”), who was “the young flower-solar deity”

(Nicholson 1963: 22). Interestingly, Macuilxochitl

is a male god in the same water-agricultural fertil-

ity deity complex as Chicomecoatl, and represents

the influence of solar heat over agricultural

fertility (Nicholson 1971: 417). At the same time,

we suggested above that the five-flower or seven-

flower headband worn by these figures may also

connect with modern Nahua beliefs about twin

corn spirits: one female, called “5-Flower,” and

the second male, called “7-Flower” (Sandstrom

1991: 245). Sandstrom associates both of these

corn spirits with pre-Hispanic Aztec deities:

“Seven-flower ... was related to Pilzintecutli, the

lord of young maize ... Five-flower was patron of

dances, games, and love and was the sibling of

Centeotl, the ‘God of Corn’” (1991: 145; see also

Caso 1958: 46-47).

Furthermore, stories about Maize Gods/

Maize Heroes (often twins, sometimes female-

male, and other times both males) are abundant

in modern Indigenous mythologies across

Central America and Mexico, and especially

along the Gulf Coast (Braakhuis 2009; Chincilla

2017; Sandstrom 1991). These Maize Gods or

Maize Heroes are associated with the Sun, Rain

and Lighting-Thunder Gods (Braakhuis 2009;

Chinchilla 2017; Sandstrom 1991), which may

explain why we see such associations in the WAM

sculpture, or at least suggest that those associa-

tions are not unusual. After all, maize agriculture

requires both water and sun.

Nicholson’s analysis of this group of Aztec

fertility goddess statues concluded that the differ-

ent elements of these teixiptlahuan were discrete

markers of individual deities, brought together

into one statue. According to his interpretation,

the WAM fertility goddess emphasized the

combination of overall divine forces that perme-

ate various aspects of life, such as corn, fertility,

and water (Nicholson 1963). These teixiptlahuan

would then be a potent representation of teotl

as a life force or vital essence that transcended

individual deities, and instead permeated and ex-

isted between all divinity in Nahua thought as “a

numinous impersonal power diffused throughout

the universe” (Pohl and Lyon 2010: 34).

Reinterpretation of the WAM Fertility

Goddess Statue

While not denying the pantheistic nature of Aztec

religion (as described above), a closer look at

the WAM fertility goddess suggests a different

interpretation of which deities—and even how

many—are depicted in the statue. Many scholars

have pointed to the interrelated nature of Mexica

fertility and water deities. Townsend (2009),

Nicholson (1971), and more recently Paulinyi

Revue de la culture matérielle 88-89 (Automne 2018-Printemps 2019) 9

(2013), have all outlined the existence of a Mexica

fertility and water goddess complex, with parallels

in male gods and relationships to deities from

the older Teotihuacán civilization. This complex,

titled Rain-Moisture-Agricultural Fertility by

Nicholson (1971), included five major sub-

complexes: 1) the Tlaloc subcomplex for deities

associated with water, rain and moisture; 2) the

Centeotl-Xochipilli subcomplex for deities related

to maize, flowers, sun warmth, pleasure, singing

and dancing; 3) the Ometochtli subcomplex of

deities associated with the maguey plant and the

alcoholic drink pulque, which is made from the

plant (called octli in Nahua); 4) the Teteoinnan

subcomplex for earth mother goddesses, includ-

ing Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina, Cihuacoatl, Coatlicue,

Tlazolteotl, Itzpapalotl, and Xochiquetzal; and,

5) the Xipe Totec subcomplex of gods related to

fertility and renewal—best known for the flaying

of the sacrificed individual and the wearing of the

skin by the priests (Nicholson 1971).

These gods often appear in male-female pairs,

including Tlaloc (Rain God) and Chalchuihtlicue

(goddess of streams, rivers and lakes), and

Ometochtli (god of pulque) and Mayahuel (god-

dess of the maguey plant). Such male-female pairs

strongly support gender dualism and comple-

mentarity rather than gender hierarchy (see also

discussion in McCafferty and McCafferty 1988).

Two such male-female pairs are present among

maize deities. One of these existed between

Xilonen (“She of the Tender Maize Ear”) as the

goddess of young, green corn, and Piltzintecuhtli

(Young Maize Lord). The Mexica also paired

Chicomecoatl, the goddess of mature maize, with

Centeotl, the Mature Maize God.

As agricultural fertility and rain/water were

intertwined, Mexica deities such as Chicomecoatl,

Chalchiuhtlicue, and their male counterparts,

Centeotl and Tlaloc, were all associated with both

fertility and water. They shared some combina-

tion of identifying features, including images

of corn, headbands, flowers, tassels, garments,

and colour associations. Recognizing these

teteo’s nature as a complex of deities with shared

diagnostic features makes it unnecessary to treat

all features as signifiers of a specific individual

deity. This approach opens the door to examining

the WAM statue as a single goddess.

If the statue is treated as a teixiptla represent-

ing a single goddess, several characteristics fall

into place. First, it becomes clear that associations

with the water goddess Chalchiuhtlicue may

simply be a product of shared features amongst

the fertility deity complex. The possible chal-

chihuitl and black cheek bars can be explained

through shared symbols of divinity, instead of

being exclusive markers of Chalchiuhtlicue.

Although Nicholson points to their association

with Chalchiuhtlicue and water, they are found

on statues which are definitively representations

of Chicomecoatl or Xilonen (see Fig. 5 or 2b). The

WAM teixiptla’s red colouring would also make

more sense if it is not an image of Chalchiutlicue,

who is usually depicted with the colours blue,

white, or green (Nicholson and Berger 1968:

10-12). The chalchihuitl jade ornament on the

WAM statue may simply associate it with the

preciousness of jade or even with its green

colour that symbolizes verdant growth, charging

the statue with additional valences of fertility,

without necessarily linking it with the goddesss

Chalchiuhtlicue.

Alternatively, these multiple references to

water may be interpreted in a different way,

following Sellen’s analysis of Zapotec storm-god

effigy vessels and censers (2002). Sellen suggests

that important rain rituals attended the maize

agricultural cycle, especially at the stages of early

corn sprouting and young green corn, a critical

moment in the maturing of the crop, when the

right amount of rain or water was required for

its growth. Because of the importance of water

to young corn, symbols of both corn and water/

rain deities were combined in these effigies to

ensure an abundance of rain to the young maize

crop (Sellen 2002). In the case of the WAM Aztec

statue, the rain-associated black marks on her

cheeks and the chalchihuitl jade pendant may

have served to ensure that sufficient rain arrives

to the young plants.

Based on this line of thought, the WAM Aztec

statue does not embody Chalchiutlicue but rather

one of the other two female maize goddesses

within the fertility complex, either Chicomecoatl

or Xilonen, as suggested by the maize cobs in the

statue’s headdress. The WAM goddess’ flower

headband also points to a relationship with a

maize deity instead of Chalchiuhtlicue. Nicholson

and Berger’s (1968: 10) analysis of Aztec fertility

goddess statues point to a different headband

associated with Chalchiuhtlicue, which consists

10 Material Culture Review 88-89 (Fall 2018-Spring 2019)

of three bands wrapped around the head, tied

with a big knot in the back, and decorated with

circular elements (possibly cotton balls) above

and below the bands (see Fig. 3). Furthermore,

the Chalchiuhtlicue headbands are usually

coloured in white or blue, and only rarely in red

(1968: 10). Different headband colours are very

important as they correlate to individual deities:

while Chalchiuhtlicue is strongly associated with

blue (Nicholson and Berger 1968: 10), Xilonen

and Chicomecoatl have been associated with the

colour red on their faces, clothing, and adorn-

ments (Grigsby and de Leonard 1992).

Descriptions of the major festivals cel-

ebrating Xilonen and Chicomecoatl before the

Spanish Conquest provide more insight into the

identification of the WAM statue as Xilonen or

Chicomecoatl. Xilonen was celebrated during

the eighth of eighteen veintenas, or twenty-day

months of the Mexica solar calendar of 365 days

(Grigsby and de Leonard 1992: 115). This period

lasted from July 5th to 24th, and was known as

Huei Tecuilhuitl, or the Festival of the Great Lords

(Paulinyi 2013: 135). Huei Tecuilhuitl coincided

with the time when the first tender green maize

becomes ripe in the Valley of Mexico, an apt

moment to celebrate the goddess of young maize

(135). On the tenth day of the month, a young

woman costumed as Xilonen’s teixiptla was

sacrificed after eight days of eating, dancing, and

singing in public spaces (Sahagún 1950-1982,

Book II: 14-15; 96-107). Sahagún describes how

the Xilonen teixiptla was dressed comparably to

the WAM’s statue:

Her face was painted in two colors: she was

yellow about her lips, she was chili-red on

her forehead. Her paper cap had [maize]

ears at the four corners; it has quetzal

feathers in the form of maize tassels; ...

Her neck piece consisted of many strings

of green stone; a golden disc went over

it. {She had} her shift with the water lily

{flower and leaf design}, and she had her

skirt with the water lily {flower and leaf

design} ... Her shield and her rattle stick

were chili-red. (Sahagún 1950-1982: Book

II, 103)

The woman was decapitated after being

dressed in this manner, and allowed to play music

using her red rattle (Both 2010; Dodd Pennock

2018: 291). Only after her sacrifice were people

permitted to eat tortillas of green maize and the

cane of green corn (Sahagún 1950-1982: Book II,

105; Frazer 1999). Women, known as Xilonen’s

offering priestesses, danced for the goddess before

her sacrifice:

Likewise the women danced, those who

belonged to Xilonen. They were pasted

with red feathers and they were painted

with yellow ocher. Also, thus were their

faces divided: they were yellow with ocher

about the lips, and they were light red with

arnotto on their foreheads. They had their

wreaths of flowers upon their heads; their

garlands of tagetes flowers went leading.

(Sahagún 1950-1982: Book II, 104)

The costumes of the Xilonen teixiptla and

priestesses share several features with the WAM

statue. The priestesses wore wreaths of flowers

just like the flower garland of the WAM sculpture.

The teixiptla and priestesses were painted red

(although only on their foreheads), but they also

carried other red elements in their attire; the

WAM statue is completely red. The teixiptla had

maize ears and quetzal feathers in her headdress

and so does the WAM effigy.

While Xilonen was celebrated in the eighth

month of the Mexica solar year, Chicomecoatl

and Cinteotl/Centeotl were celebrated in the

fourth month, called Huey (Uei)Tozoztli, or Great

Vigil (Sahagún 1950-1982: Book II, 7-9, 61-65),

which started April 13 (Durán 1971: 422). The

festival dedicated to Chicomecoatl and Centeotl

began with four days of fasting by all people, as

well as the decoration of their houses with reeds

or fir branches sprinkled with sacrificial blood

(Sahagún 1950-1982: Book II, 7, 61). Meanwhile,

the calpulli (clans, wards) temples were cleaned,

atole was prepared by the women, and small

maize stalks gathered from the fields and deco-

rated with flowers were placed there as offerings

to the gods (Sahagún 1950-1982: Book II, 7,

61). Sahagún describes how the youths and the

priests “departed to their fields, to get Centeotl.

In as many places as lay their fields, from each

field, from each they went to take a stalk of green

maize” (Book II, 62). The young girls then carried

mature ears of maize on their backs to Cinteopan,

the temple-pyramid dedicated to Chicomecoatl,

to be blessed by the goddess (Book II, 7, 63).

There they “enacted skirmishes in the manner

Revue de la culture matérielle 88-89 (Automne 2018-Printemps 2019) 11

of battles” (Book II, 7) and exhorted the young

warriors to be courageous (Dodds Pennock 2018:

297). The blessed maize was later taken home

to be the planting seed for the following year

(Sahagún 1950-1982: Book II, 7, 63). The girls

“bound the cobs of maize in groups of seven ...

and wrapped them in paper which was reddened”

(Book II, 63). They were themselves adorned with

red feathers on their arms and legs, and their faces

were painted; “on each they stuck two {circles} of

tar, which were flecked with iron pyrites” (63).

In the temple’s courtyard, the Chicomecoatl

teixiptla was created out of dough: “They formed

her image as a woman. They said: ‘Yea, verily,

this one is our sustenance; that is to say, indeed,

truly she is our flesh, our livelihood; through

her we live; she is our strength’” (64). Sahagún

then describes how the Chicomecoatl effigy was

adorned:

she was anointed all in red

3

— completely

red on her arms, her legs, her face. All her

paper crown was covered completely with

red ochre; her embroidered shift also was

red [and decorated with water flowers] [...]

The ruler’s shield was painted with designs,

embellished in red. She was carrying her

double ear of maize in either hand. (Book

II, 65, Book I, 13)

All types of food, especially of maize, were

presented as gifts to her because “they said that

she was the maker and giver of all those things

which are the necessities of life, that the people

may live” (7). After more dancing and singing,

the Great Vigil ended (65). The anointing of the

Chicomecoatl effigy in red paint is strikingly

similar to the all red WAM statue. However, in

contrast to the Xilonen teixiptla who had corn in

her headdress, the Chicomecoatl teixiptla held

the double ear of maize in her hands. Beyond the

direct links between these festivals and the WAM

statue, these rituals are important because they

show that women played active and central roles

as priestesses, dancers, participants, teixiptla,

and goddesses.

Although the rituals and iconography

described above link the WAM statue with both

Chicomecoatl and Xilonen, we suggest that

the WAM statue’s creator implied its status as

the latter. Both Chicomecoatl and Xilonen are

fertility goddesses closely associated with maize

Figs. 6a, b (below) and c (next page)

The growth of a maize cob (a cob is the fertilized female

part of the plant): a. Young maize with silk. Fertilization

begins on the bottom of the cob and travels upwards to

its tip, producing mature kernels along the way. As the

cob matures, maize silk is present amongst the youngest

or unfertilized areas, occupying an ever-decreasing area

towards the cob’s tip. © RL Nielsen, Purdue University;

Nielsen 2016; b. a tuft of silk falls like yellow hair at the top

(or end) of the maize cob, and does not occur in unhealthy

cobs. © RLNielsen, Purdue University; c. fully fertilized or

mature cob has little to no silk. Image courtesy Encyclopedia

Britannica.

12 Material Culture Review 88-89 (Fall 2018-Spring 2019)

and plant growth, and therefore share many

diagnostic characteristics. In pictorial depictions,

the two deities are sometimes indistinguishable

(Paulinyi 2013: 88). But Chicomecoatl is linked to

the mature maize plant, while Xilonen is closely

related to young green maize. With this in mind,

the significance of the fine and long silk tassels

falling from the maize cobs on both sides of the

statue’s headdress becomes clear (Fig. 1). Young

cobs are characterized by maize “silk”—long, thin

fibers that emerge from undeveloped kernels (Fig.

6a). A maize cob before full maturation ends up

with a long tassel of silk at its upper end (Fig. 6b),

while the cob has many developed kernels below

(Nielsen 2016), something depicted exactly in the

WAM statue, which shows fibers falling from the

tip of a cob with mature kernels (Fig. 1c). At full

maturation, maize has little to no silk (Fig. 6c).

Furthermore, it is worth pointing out that silk,

and maize cobs, only occur on female flowers.

Thus the WAM statue, with its full tassels of fine

silk framing the corn cobs, presents young green

maize and femininity, and points to Xilonen—the

virgin deity of young maize—instead of the

mature Chicomecoatl.

The WAM statue, as well as the other six in

Nicholson’s group, are differentiated from the

most common images of Chicomecoatl which

are rendered with a very distinct rectangular

headdress as seen in Figs. 4, 5, 7. Typically,

Chicomecoatl is shown wearing a massive rec-

tangular paper headdress, called amacalli (“paper

house”), with two to four rosettes at its corners

(Nicholson 1963: 9; Pasztory 1983: 218). She usu-

ally carries two maize ears (cemmaitl) in one or

both hands, rather than having these corncobs in

her headdress (Nicholson 1963; Pasztory 1983).

Xilonen is also sometimes shown with a ritual

amacalli headdress, often ornamented with a

quetzalmiahuayotl plume (Evans 2004: 405). As

seen in Figs. 4, 5 and 7, Chicomecoatl’s headpiece

is one of the most ornate in the Mexica pantheon,

and is extremely similar across different depic-

tions. Chicomecoatl’s ever-present headdress is

easily distinguishable from the WAM statue’s

ornamentation.

Nevertheless, the close link between Xilonen

and Chicomecoatl is brought to life in that three

of the seven statues in this group are carved

with the calendrical name “Seven Serpent” or

Fig. 6c (above)

Fig. 7 (left)

Chicomecoatl’s large

paper headdress,

amacalli, which is

consistent across

depictions such as this

statue. Note that she

holds the double ear of

maize in both hands.

The Metropolitan

Museum of Art,

accession no. 00.5.28.

Revue de la culture matérielle 88-89 (Automne 2018-Printemps 2019) 13

Chicomecoatl. We suggest that this does not

contradict our identification of the WAM Aztec

statue as Xilonen, but rather connects Xilonen

with the life force, destiny or tonalli of the mature

Maize Goddess, inherent in the calendrical name

of “7-Serpent” or Chicomecoatl. As Xilonen and

Chicomecoatl are deities of the same substance

(maize) across different stages in time, their ton-

alli is similarly related if not completely shared.

Features of the WAM statue of Xilonen and

comparable effigies reveal some of the ways that

teixiptlahuan were treated by the Mexica. During

ceremonies, revered teixiptlahuan were often

dressed in real garments, feathers, and valuables

(Berdan 2007). The Art Institute of Chicago’s

statue of Xilonen (Fig. 1b) has holes on either

side of its neck where a necklace would have been

inserted (Art Institute of Chicago, n.d.). Similar

decorations may have adorned the WAM piece,

but this is less likely because it has no holes and

it is already depicted with two necklaces. The

depressions in the eyes and/or mouth of these

statues are also significant because they may

have held inlays of shell, obsidian, pyrite, or bitu-

men (tar) (Nicholson 1963: 11). Bassett (2015)

describes how such inlays, common in Aztec

statues, gave sight to the depicted gods, because

the reflective materials inserted in the eyes made

the statues appear to be returning one’s gaze. This

enlivens the sculpture with the vital animacy

(life force, tonalli, etc.) of that deity. The dressing

and/or adornment of effigies continues to be an

important part of modern Nahua ceremonies

(see below).

The physical origins of the WAM statue are

unclear, but Nicholson (1963) traces the group

to the Toluca basin, west of modern-day Mexico

City. The Toluca basin was conquered in 1475-76

by the Mexica Emperor Axayacatl (r.1469-1481)

(Townsend 2009: 99) and actively participated

in Mexica sculptural tradition by the time of

Cortés’ arrival (Nicholson 1963: 21). After the

Aztec conquest, the valley site of Calixtlahuaca

was transformed into a Mexica colony by bring-

ing in Aztec colonists from the Valley of Mexico

(Townsend 2009: 106). Although five of these

statues have no provenance, two are known to

be from the Toluca basin, and one specifically

from the site of Tenancingo in the Toluca Valley

(Nicholson 1963). Based on the known proveni-

ence of these two statues in the group and their

high similarity in style and iconography, we sup-

port Nicholson’s conclusion that all were probably

manufactured by closely-aligned sculptors who

may have been originally based in a local school

of carving in the Toluca Basin (Nicholson 1963;

Pasztory 1983).

Maize Goddesses and Aztec Gender

Dynamics

The WAM statue, together with Nicholson’s group

of six highly similar goddesses and the hundreds

of other fertility goddesses, provides a caveat to

ideas about pre-Hispanic Mexica gender-power

dynamics. Here we are not talking about the

political rituals conducted by the Aztec emperor

or the imperial priesthood, which may have been

imbued with the overarching Mexica male war-

rior (more misogynist) ideology (Conrad and

Demarest 1984). Instead, we want to better un-

derstand the general society and its general views

on gender dynamics. Nash (1978, 1980), Klein

(1988, 1993, 1994) and Clendinnen (1991) have

concluded that Mexica women were oppressed in

a male-dominated society. However, authors such

as Joyce (2000), Kellogg (1995), McCafferty and

McCafferty (1988, 1999), and Dodds Pennock

(2008, 2018) have suggested a more equal rela-

tionship between men and women in the Mexica

world. First, Joyce (2000) and Kellogg (1995) have

pointed out that the male bias of the Spanish

accounts may have influenced the Conquistadors’

description of the Mexica. Second, the frequency

of male-female deity pairs as described here in the

case of the maize goddesses and gods, suggests

gender complementarity. As mentioned above,

Xilonen (the Young Maize Goddess) was paired

with Piltzintecuhtli (the Young Maize Lord), and

Chicomecoatl (the Goddess of Mature Corn) was

paired with Centeotl (the God of Mature Corn).

Third, McCafferty and McCafferty (1988)

describe the opportunities afforded Mexica

women to rise in status, wealth, and power in the

trade guild (pochteca), in the marketplace (where

women not only sold a variety of goods, but also

served as administrators), in the production and

sale of cloth and textiles, and in the priesthood

(where women officiated in rituals, but also

served as curers and midwives). They conclude

that Mexica gender relationships were not

14 Material Culture Review 88-89 (Fall 2018-Spring 2019)

hierarchical, but in dialectical opposition (47). In

a similar fashion, Kellogg (1995) concludes that

Mexica gender dynamics can be seen as gender

parallelism.

Fourth, Joyce underscores that both male

and female deity impersonators were sacrificed

during annual festivals, and that both females and

males were encouraged to think of themselves

as warriors defeating Huitzilopochtli’s elder-

siblings, known as Huitznahua, when they con-

quered neighbouring lands (2000: 168-69). The

McCafferties (1988: 50) also note that females

were represented as warriors: for example, the

goddess Xochiquetzal was a warrior when she

manifested as her coessence Itzpapalotl (Obsidian

Butterfly); women giving birth were described as

warriors in battle (Sahagún 1950-1982: Book VI,

167), and if they died during childbirth, they were

deified as the Sun’s companions, just like men

who died in battle (Sahagún 1950-1982: Book II,

37, Book VI, 162-63).

Fifth, Dodds Pennock also notes that far

“from being oppressed, many women in Aztec

culture were respected and influential” (2018:

277). She notes that “there is little evidence for

the patriarchal ‘policing’ of female bodies” in

Aztec society because divorce was allowed from

either husband or wife, because of the absence

of primogeniture, and because of the emphasis

on fathers to care for and raise their sons after

weaning (277). Her analysis of female power in

Aztec thought led her to conclude that “in mytho-

historical terms [women] ... often exceeded their

male counterparts in importance” (2018: 278).

Finally, the exquisite detail of the WAM piece

and the other similar statues suggests great appre-

ciation of Xilonen and Chicomecoatl. Even more

importantly, the close similarity between WAM,

the Mexican Museo de Antropologia statue (Fig.

2a) and Chicago’s Xilonen (Fig. 2b) teixiptlahuan

imply an established and standardized system of

representation for that goddess. Authors such as

Evans (2004) have suggested that Aztec gender

imbalances led to central, urban sites being dedi-

cated to male deities, while female goddesses were

mainly worshipped informally amongst rural

communities. We disagree with this interpreta-

tion, as the WAM and Chicago Xilonen statues,

with their high craftsmanship and standardized

themes, highlight that the Aztec state was invested

in creating multiple unified and easily recogniz-

able portrayals of female goddesses for central

temples, not only for households among small,

rural communities. In particular, the Chicago

Art Institute Xilonen sculpture was of a scale

worthy of an urban temple: its preserved head

measures 32.4 x 20.3 x 12.1 cm, basically larger

than life-size, and originally it would have been

at least twice as large (Nicholson 1963).

e Enduring Power of Maize Dual-

gender Gods in Modern Mesoamerica

Among modern Nahuatl-speaking communities

of Veracruz on the Gulf Coast of Mexico, corn

remains the most important enduring symbol.

Sandstrom writes:

Chicomexochitl [7-Flower, male aspect of

the corn spirit] ... is more than a mythic

culture hero symbolizing the central

importance of corn in Nahua life. It plays

a deeper metaphysical role in the Nahua

view of the universe and the place of

human beings in the natural order.... In

Nahua thought, human beings are part

of the sacred universe, and each of us

contains within our bodies a spark of the

divine energy that makes the world live.

This energy ultimately derives from the

sun, toteotsij. [...] This energy is carried

in the blood (estli in Nahuatl), and it is

renewed when we consume food, particu-

larly corn. [...] Corn, then, is the physical

and spiritual link between human beings

and the sun. (1991: 246-47)

In the Nahua pantheon in Amatlán, Veracruz

(the village studied by Sandstrom), corn is the

principal of the seed spirits, who resides with

their mother Tonantsij (earth mother) in a cave,

which “is also occupied by thunder (tlatomoni in

Nahuatl) and lightning (tlapetalani in Nahuatl),

spirits which are associated with the rain dwarfs”

(247). Thus, there is a close association between

the maize, earth, and rain gods, all so important

for agricultural fertility. As mentioned earlier,

the corn spirit was seen as twins, one male and

one female: Chicomexochitl (“7-flower”) was the

male twin, and Macuilixochitl (“5-flower”) was

the female twin (245).

The centrality of corn to modern Nahua peo-

ple and more generally to all Indigeneous groups

Revue de la culture matérielle 88-89 (Automne 2018-Printemps 2019) 15

of Central America and Mexico, is underscored

by the dominance of myths about the Maize

God or Maize Hero, sometimes seen as twins

(including male and female pairs). Sandstrom

(1991) collected several such myths in Huasteca

Veracruzana during 1985 and 1986. These myths

follow the same patterns seen across a broad ex-

panse of Mesoamerica, as discussed by Braakhuis

(2009) and Chinchilla Mazariegos (2017). In

one story, “the grandmother of chicomexochitl

kills him and tries to hide the body.... No matter

what she does he reappears to face her with the

crime,” pointing to the constant rebirth of corn

even though it is “killed” at the yearly harvest or

when the corn is eaten by humans (Sandstrom

1991: 245-46). In variations of this story, the

grandmother kills the Maize Hero and throws

him in the water where he is rescued or reborn

(Braakhuis 2009; Chinchilla Mazariegos 2017).

Another story connects the Maize Hero with his

father, the Deer Spirit, called masatl in Nahuatl,

whom the hero tries to resuscitate (Braakhuis

2009; Chinchilla Mazariegos 2017; Sandstrom

1991: 246).

Another myth from Amatlán recounts how

corn was rediscovered. Chicomexochitl withdrew

to live inside a sacred mountain called Postectitla

(Sandstrom 1991). Without corn,

the villagers went hungry. One day people

saw red ants carrying grains of corn

emerging from a cave in the mountain. At

this point, the water spirit sa hua struck

the moutain, causing the peak to break

off and allowing fire to escape from inside

the earth. Thunder and lightning spirits ...

sprinkled water on the fire to prevent the

corn from burning, but were only partially

successful. (246)

It led to the invention of white, yellow, red, and

black corn varieties (246).

The parallel between this story and that told

by Q’eqchi Maya is uncanny: in a time before

maize, when mankind ate only fruits and roots,

a fox found leaf-eating ants carrying maize

grains, and when he tried it, he liked it very

much (Thompson 1930: 132). When all the other

animals tried the corn and liked it, they told man

who asked the Mams, lords of the mountains,

the plains and thunder, to help them reach the

corn that was locked away inside a mountain

(132). Yaluk, the greatest of the Mams, struck the

mountain at its weakest point:

when the thunderbold burst the rock

asunder, it had burnt much of the maize.

Originally all the maize had been white,

but now much of it had been badly burnt

and had turned red. Other grains were

covered with smoke, and they had turned

yellow. This is how the red and yellow

maize originated. (Thompson 1930: 134)

While details and names differ, there are so many

similarities between the mythology of the Maize

God(s)/Hero(es) across Mesoamerica to suggest

that these stories are predicated on common ideas

shared by Indigenous groups.

Maize is also at the heart of ritual life among

modern Nahua. For example, in Amatlán,

Veracruz, one of the most important rituals is

called Chicomexochitl after the maize spirit

(Sandstrom 1991: 286-88). It takes place in late

February or early March, in honor of the seed

and rain spirits, and to ensure crop success and

rain (Sandstrom 1991: 286-88). It is an elaborate

ritual lasting 12 days (286). A main altar is built

inside the house of the sponsor. Upon it sits the

most important object of the ritual: a sealed box

with seed effigies made out of paper. Sandstrom

describes the next stages of the ritual:

The shaman directs assistants to open

the seed box and to remove and wash the

clothes worn by the paper images. As the

clothes are drying on the line, assistants

lean the naked seed children up right at

various places on the altar table and on the

earthen floor below. After the cleansing

outside in which he expels dangerous

ejecatl or wind spirits, the shaman enters

the house followed by helpers carrying live

turkeys and chickens. The shaman grabs

a large bird, cuts its throat with a pair of

scissors, and carefully drips the blood

over the large array of paper images laid

on the altar. He repeats this with several

additional sacrificial birds, taking care

that blood falls on to the paper images and

adornments on the floor that forms the

display to the earth. He then fills a shallow

dish with blood, and using a turkey feather

as a brush paints each paper image with

it. When I asked what he was doing, he

replied, “This is their food.” (1991: 287)

16 Material Culture Review 88-89 (Fall 2018-Spring 2019)

Additional altars are built and decorated with

“paper images, leaf and marigold adornments,

and copious food and drink offerings” (287).

Among these, two altars are specifically dedicated

to the fire spirit and the water spirit, while a third

one in the form of a cross is dedicated to the sun

(287). During the next eleven days, off and on,

chanting, dancing, and offerings are given to the

spirits in front of the altar as copal smoke rises

and surrounds the altars and the people (287).

The twelfth day is the culmination and end of

the ritual: new offerings are placed on the altars,

the seed box is refilled with the paper images

which have been redressed in their clean clothes

and even decorated with additional jewelry.

Meanwhile,

the shaman chants intensely. In his chant

he lists the offerings and implores tonatsij

[the earth mother] and her children, the

seeds, to support the village in the year

to come. He chants before each altar,

beseeching the sun, water, and earth to be

kind to the people even though they often

offend the spirits through their activities

and occasional evil intentions. (Sandstrom

1991: 288).

A similar ceremony, also called

Chicomexochitl, was observed by Bassett (2015)

in a different locality in the same Huasteca

Veracruzana region during the summers of 2006

and 2010 (14-25). Just like in Amatlán, the main

gods propitiated in this ritual are paper effigies

embodying the Chicomexochitl family, and the

primary goal of the ritual is to ensure the arrival

of rain for the crops (21). Bassett describes the

creation of these effigies as a critical process of

animation: “

During this ... annual celebration, partici-

pants manufacture a family of six totiotzin

[gods], and in the process, the inanimate

objects [the paper figures] ceremonially

transform into animate entities, a ritual

act that effects change along the spectrum

of animacy.... Over a period of a few days,

the tepahtihquetl (ritual officiant [or sha-

man]) cuts ordinary store-bought amatl

(paper) into tlatecmeh (paper figures of

natural deities used in ceremonies) that

come to embody the highly animate

Chicomexochitl, Tohueyinanan (mother),

Tohuehitatah (father), and their four

children, whom participants venerate

throughout the year. (15)

The Chicomexochitl are seen as boys and

girls, who are adopted by the family sponsoring

the ritual, and feted throughout the year by this

same family (Bassett 2015: 21). Although Bassett

does not clarify which gods Chicomexochitl rep-

resents, it is quite likely that they are all four maize

spirits, not only because they have the name of

the Maize God among the Nahuatl speakers of

the Gulf Coast (Braakhuis 2009), but also because

they are children, both male and female, as the

male and female corn twins of Amatlán.

The ritual culminates in the pilgrimage of the

whole community to the summit of their sacred

mountain, called Xochicalco (“Flower House”

in Nahuatl) which is considered the home of the

Chicomexochitl (Bassett 2015: 17-18). Bassett

described the ceremony thus:

Once the group arrives on the altepetl’s

summit, the Tepanhtihquetl hangs the

bag containing the Chicomexochitl

effigies above the center of the summit’s

principal altar. [...] Participants cover the

largest altar table with sheets of paper

cutouts representing beans, corn and

chilies. Members of the sponsoring family

hold two chickens and a turkey while the

tepahtihquetl feeds them sips of soda and

beer. After ‘intoxicating’ the birds with

these luxury beverages, the tepahtihquetl

uses scissors to cut their necks.... The birds’

blood soaks into the paper cutouts and the

earth. (2015: 19-20)

The many similarities between this ceremony

and the ritual by the same name observed by

Sandstrom in Amatlán illuminate the continuing

centrality of maize in the lives of modern Nahua

people, the descendants of the pre-Hispanic

Aztecs. Where modern Nahua communities

render Maize Gods in cutout paper effigies, their

ancestors represented those same deities in stone,

as in the WAM Aztec statue.

Conclusions

The WAM statue features symbols and charac-

teristics that can be individually attributed to

multiple Aztec deities. But a close analysis of the

statue suggests that it embodies a specific maize

Revue de la culture matérielle 88-89 (Automne 2018-Printemps 2019) 17

deity, instead of being an amalgamation of multi-

ple divine figures. Comparing the statue to others

described by Nicholson (1963) and examining

several of its major components—perhaps most

importantly, its headdress—reveals the statue as

Xilonen or Xilonen-Chicomecoatl, who are both

important female maize deities only separated by

their identification with different stages in maize

growth. The WAM statue’s characteristics most

closely align with those of Xilonen, the goddess

of young maize. Features on the statue which

are often associated with other divinities (such

as the chalchihuitl stones or the black bars on its

cheek) are likely general markers of divinity and

value, or signs that encourage rain for the young

maize plants.

Notes

The WAM statue as a young female maize

deity supports the idea of Aztec religion not as

the misogynistic ideology that modern scholars

sometimes argue it is. Instead, the male-female

duality that is found with Maize Gods/Goddesses

and other divine figures attests to a profoundly

complementary gender dynamic. The importance

of this male-female duality continues from pre-

Hispanic times into modern Nahua rituals, such

as those studied by Sandstrom and Bassett in

modern-day Veracruz.

We would like to thank the curatorial staff of the

Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts

and of the Williams College Museum of Art,

Williamstown, MA, especially Jon Seydl, previously

the Director of Curatorial Affairs and Curator of

European Art at the Worcester Art Museum, and

Elizabeth Gallerani, Mellon Curator of Academic

Programs at WCMA. Their help was indispensable

and made this research possible. We would also

like to thank the two anonymous reviewers whose

comments greatly improved this work. All errors of

fact and interpretations remain our own.

1. This red pigment is highly significant as red is the

colour of blood, and tonalli, one of the life forces,

is found in blood according to the pre-Hispanic

Aztecs and their descendants, modern Nahua

people (Furst 1995; Sandstrom 1991). Blood

was also the preferred offering to the gods in

pre-Hispanic times. Even today, in Nahua ritu-

als, blood from sacrificed birds is brushed onto

paper cult figures representing deities or spirits

(Sandstrom 1991; see also further discussion in

the latter sections of the article).

2. The six statues are: (1) Museo Nacional de

Antropología, Mexico City, no. 11.0-02997

(Nicholson 1963: Fig. 6); (2) British Museum,

London, according to Nicholson, but the artifact

could not be located in 2020, so its location is

unknown (1963: Fig. 7); (3) Museo de Historia

y Arqueología, Toluca, Mexico (1963: Fig. 8); (4)

Palacios Collection, and now in Metropolitan

Museum, New York, no. 1979.206.1386 (1963:

Fig. 9); (5) Museum of Primitive Art, previously,

and now Metropolitan Museum, New York, no.

1979.206.407 (1963: Fig. 10); and (6) the McNear

fertility goddess now at the Art Institute of

Chicago, no. 1986.1091 (1963: Figs. 1-3).

3. Durán (1971: 222) also describes Chicomecoatl’s

teixiptla, confirming that all her garments were

red, as well as her paper tiara. As Chicomecoatl

was the deity of harvest, Durán places the

great festival honoring Chicomecoatl in early

September rather than April.

18 Material Culture Review 88-89 (Fall 2018-Spring 2019)

Primary Sources

Durán, Fray Diego. 1971. Book of the Gods and

Rites and The Ancient Calendar. Trans. and ed.

Fernando Horcasitas and Doris Heyden. Norman:

University of Oklahoma Press.

Sahagún, Bernardino de. 1950-1982. Florentine

Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain.

Trans. and Ed. Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles

E. Dibble. Santa Fe, NM: School of American

Research and University of Utah.

Keber, Eloise Quiñones. 1995. Codex Telleriano-

Remensis: Ritual, Divination and History in a

Pictorial Aztec Manuscript. Austin: University of

Texas Press.

Secondary Sources

Art Institute of Chicago. Family Activity: Maize

for All Seasons. Interpretive Resource. http://

www.artic.edu/aic/resources/resource/1047

(accessed May 09, 2018).

Bassett, Molly H. 2015. The Fate of Earthly Things:

Aztec Gods and God-Bodies. Austin: University of

Texas Press.

Berdan, Frances F. 2007. Material Dimensions

of Aztec Religion and Ritual. In Mesoamerican

Ritual Economy: Archaeological and Ethnological

Perspectives, ed. E. Christian Wells and Karla L.

Davis-Salazar, 245-66. Boulder, CO: University

Press of Colorado.

Both, Arnd Adje. 2010. Aztec Music Culture. The

World of Music 52 (1/3): 14-28.

Braakhuis, Henry E.M. 2009. The Tonsured Maize

God and Chicome-xochitl as Maize Bringers and

Culture Heroes: A Gulf Coast Perspective. Wayeb

Notes 32: 1-38.

Broda, Johanna. 1991. The Sacred Landscape

of Aztec Calendar Festivals: Myth, Nature, and

Society. In Aztec Ceremonial Landscapes, ed.

William Fash and David Carrasco, 74-120. Niwot,

CO: University Press of Colorado.

Brumfiel, Elizabeth M. 1991. Weaving and

Cooking: Women’s Production in Aztec Mexico.

In Engendering Archaeology: Women and

Prehistory, ed. Joan Gero and Margaret Conkey,

224-251. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

———. 1996. Figurines and the Aztec State:

Testing the Effectiveness of Ideological

Domination. In Gender and Archaeology, ed.

Rita Wright, 143-66. Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press.

Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo. 2017. Art and

Myth of the Ancient Maya. New Haven: Yale

University Press.

Clendinnen, Inga. 1991. Aztecs: An Interpretation.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Conrad, Geoffrey and Arthur A. Demarest. 1984.

Religion and Empire: The Dynamics of Aztec and

Inca Expansionism. New York City: Cambridge

University Press.

Diel, Lori Boornazian. 2005. Women and

Political Power: The Inclusion and Exclusion of

Noblewomen in Aztec Pictorial Histories. RES:

Anthropology and Aesthetics 47: 82-106.

Dodds Penneck, Caroline. 2008. Bonds of Blood:

Gender, Lifecycle, and Sacrifice in Aztec Culture.

Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

———. 2018. Women of Discord: Female Power

in Aztec Thought. The Historical Journal 61 (2):

275-99.

Evans, Susan 2004. Ancient Mexico & Central

America. London: Thames & Hudson.

Frazer, James George. 1999. Killing the God in

Mexico.New England Review 20 (4): 161-77.

Furst, Jill Leslie McKeever. 1995. The Natural

History of the Soul in Ancient Mexico. New Haven:

Yale University Press.

Gossen, Gary H. 1996. Animal Souls, Co-

essences, and Human Destiny in Mesoamerica.

In Monsters, Tricksters, and Sacred Cows: Animal

Tales and American Identities, ed. A. James

Arnold, 80-107. Charlottesville: University Press

of Virginia.

Grigsby, Thomas L. and Carmen Cook de

Leonard. 1992. Xilonen in Tepoztlán: A

Comparison of Tepoztecan and Aztec Agrarian

Ritual Schedules.Ethnohistory 39 (2): 108-47.

Joyce, Rosemary A. 2000. Gender and Power in

Prehispanic Mesoamerica. Austin: University of

Texas Press.

Kellogg, Susan. 1995. The Woman’s Room: Some

Aspects of Gender Relations in Tenochtitlán in

the Late Pre-Hispanic Period. Ethnohistory42 (4):

563-76.

References

Revue de la culture matérielle 88-89 (Automne 2018-Printemps 2019) 19

Klein, Cecelia F. 1988. Rethinking Cihuacoatl:

Aztec Political Imagery of the Conquered

Woman. In Smoke and Mist: Mesoamerican

Studies in Memory of Thelma D. Sullivan, ed. J.

Kathryn Josserand and Karen Dakin, 237-77.

BAR International Series 402. Oxford: Oxbow.

———. 1993. Shield Women: Resolution of an

Aztec Gender Paradox. In Current Topics in Aztec

Studies: Essays in Honor of Dr. H. B. Nicholson, ed.

Alana Cordy-Collins and Douglas Sharon, 39-64.

San Diego Museum Papers, vol. 30. San Diego:

San Diego Museum of Man.

———. 1994. Fighting with Femininity: Gender

and War in Aztec Mexico. Estudios de Cultura

Nahuatl 24: 219-53.

Lind, Michael. 2015. Ancient Zapotec Religion:

An Ethnohistorical and Archaeological Perspective.

Niwot, Colorado: University Press of Colorado.

Lopez Austin, Alfredo. 1988. The Human Body

and Ideology: Concepts of the Ancient Nahuas.

Trans. Thelma Ortiz de Montellano and Bernard

Ortiz de Montellano. Salt Lake City: University of

Utah Press.

Maffie, James. 2014. Aztec Philosophy:

Understanding a World in Motion. Boulder, CO:

University Press of Colorado.

Nash, June. 1978. The Aztecs and the Ideology of

Male Dominance. Signs 4 (2): 349-62.

———. 1980. Aztec Women: The Transition from

Status to Class in Empire and Colony. In Women

and Colonization: Anthropological Perspectives, ed.

Mona Etienne and Eleanor Leacock, 134-48. New

York: Praeger.

McCafferty, Geoffrey G. and Sharisse D.

McCafferty. 1999. The Metamorphosis of

Xochiquetzal: A Window on Womanhood in

Pre- and Post-Conquest Mexico. In Manifesting

Power: Gender and the Interpretation of Power in

Archaeology, ed. Tracy Sweely, 103-25. London:

Routledge.

McCafferty, Sharisse D. and Geoffrey G.

McCafferty. 1988. Powerful Women and the

Myth of Male Dominance in Aztec Society.

Archaeological Review from Cambridge 7 (1):

45-59.

Monaghan, John. 1998. The Person, Destiny, and

the Construction of Difference in Mesoamerica.

RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 33: 137-46.

Nicholson, Henry B. 1963. An Aztec Stone Image

of a Fertility Goddess. Baessler Archive 11 (1):

9-30.

Nicholson, Henry B and Rainer Berger. 1968. Two

Aztec Wood Idols: Iconographic and Chronologic

Analysis.Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and

Archaeology 5: 1-28.

Nielsen, Robert. 2016. Silk Development and

Emergence in Corn. Purdue University Dept. of

Agronomy. https://www.agry.purdue.edu/ext/

corn/news/timeless/silks.html (accessed May 11,

2018.

Olko, Justyna. 2014. Insignia of Rank in the Nahua

World: From the Fifteenth to the Seventeenth

Century. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of

Colorado.

Pasztory, Esther. 1983. Aztec Art. New York:

Harry N. Abrams.

Paulinyi, Zoltán. 2013. The Maize Goddess in the

Teotihuacán pantheon. Mexicon 35 (4): 86-90.

Pitarch, Pedro. 2010. The Jaguar and the Priest: An

Ethnography of Tzeltal Souls. Austin: University of

Texas Press.

Pohl, John M.D. and Claire L. Lyons. 2010.

The Aztec Pantheon and the Art of Empire. Los

Angeles: Getty Publications.

Sandstrom, Alan R. 1991. Corn is Our Blood:

Culture and Ethnic Identity in a Contemporary

Aztec Indian Village. Civilization of the American

Indian Series, vol. 206. Norman, OK: University

of Oklahoma Press.

———. 2009. The Weeping Baby and the

Nahua Corn Spirit: The Human Body as Key

Symbol in the Huasteca Veracruzana, Mexico.

In Mesoamerican Figurines: Small-Scale Indices

of Large-Scale Social Phenomena, ed. Christina

T. Halperin et al., 261-96. Gainesville: University

Press of Florida.

Sellen, Adam T. (2002). Storm-God

Impersonators from Ancient Oaxaca. Ancient

Mesoamerica 13: 3-19.

Sigal, Peter. 2011. The Flower and the Scorpion:

Sexuality and Ritual in Early Nahua Culture.

Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Townsend, Richard F. 2009. The Aztecs. 3rd ed.

New York: Thames & Hudson.