1

16.1(a)

Board Meeting, October 19, 2022

Directive 9:

Annual Equity Accountability

Report Card

Strategic Alignment:

Directive 9: Annual Equity Accountability Report Card

Report Type:

Information

Prepared by: Paul da Silva, Associate Director: School Improvement and Equity

Submitted by: Rashmi Swarup, Director of Education

2

Overview

Objective:

In accordance with Ministry Directive 9, this report includes the second Annual Equity

Accountability Report Card. The report card provides trend data from 2018-19 to 2021-22 for a

number of outcome indicators. Its purpose is to provide insights into the disproportionate

experiences of Peel District School Board (PDSB) students over the last four school years.

Background:

Following the release of the Ministry of Education Review of the PDSB in March 2020 (Chadha

et al., 2020), the PDSB has been undertaking system transformation to ensure that the well

documented and historical inequities in student achievement and experiences are eliminated.

Racism can be defined as “a series of persistent practices that systematically and unjustly

allocate advantages to certain groups and individuals” (Ryan, 1998, p. 2). In Ontario, our

education system is a colonial structure that was constructed to favour whiteness and white

Eurocentric norms. As a result, systemic discrimination creates unequal and disparate learning

outcomes for students based on their identities.

The PDSB’s mission statement asserts, “We inspire success, confidence and hope in each

student.” In order to do this, we must identify, confront and disrupt the systemic inequities that

persist today for students with particular identities and intersectional identities, most notably

those who identify as Indigenous, and African, Black and Afro-Caribbean.

The Terms of Reference of the Ministry Review required the investigators to review allegations

of systemic racism, particularly anti-Black racism (Chadha et al., 2020, p. 5). The Ministry

Review made recommendations about equity and human rights that impact all communities in

the PDSB with specific recommendations that affect African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean

communities. The authors also pointed out issues that were raised regarding South Asian

students (particularly male Punjabi students), about Islamophobia, anti-Semitism, 2SLGBQA+

students, Indigenous and Latinx/Hispanic students (Chadha et al., 2020, p. 6).

Evidence

Outline of the Report Card

The report card organizes the outcome indicators according to the Peel District School Board’s

four Board Improvement and Equity Planning focus areas:

1. Student Achievement

o Credit Accumulation

o Grade 9 and 10 Literacy and Numeracy

2. Human Rights and Equity

o Student Discipline

3. Mental Health and Well-Being

o Persistent Absences

4. Pathways and Transitions

o Special Education Designations

3

o Academic and University Pathways

o Regional Learning Choice Programs

o French Instruction

Where applicable, each of these outcome indicators are disaggregated by Indigenous and

Racial Identities, Gender Identities, Sexual Orientation (2SLGBQA+), Socioeconomic

Vulnerability Index (SVI), Individual Education Plan (IEP) Status, and English Language Learner

(ELL) Status.

Examining the outcomes in this report disaggregated by religion demonstrated two consistent

groups that experience disproportionate outcomes: students who indicated they were Christian

and those that did not affiliate with a religion. With further investigation it became apparent that

there were intersecting identities that better explained these outcomes. As a result,

disaggregated outcomes by religion are not included in this report.

Summary of Findings:

Below are some of the key finds for each focus area and emerging trends since the first Equity

and Accountability Report Card. Please review the entire report for a more detailed account.

Student Achievement:

• Consistent over-representation of identities that have been traditionally marginalized.

African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean, Indigenous, Latinx/Hispanic, Mixed Race and Middle

Eastern students have not been granted credits at the expected pace to graduate within

four years. This trend is consistent across grade levels and remains the same or

increasing across years of study, suggesting that the barriers are still pervasive, and that

racism is an active factor.

• Socioeconomic Vulnerabilities are a significant barrier to credit accumulation. Across

almost all grades and school years, students who experience very high socioeconomic

vulnerabilities accumulate fewer credits (Robson et al., 2016).

• African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean, Indigenous and Latinx/Hispanic students are most

likely to be assessed below Levels 3 or 4 in Grade 9 and 10 Academic English. These

findings indicate that while de-streaming Grade 9 Mathematics and English courses may

remove some barriers, likely there are prior gaps in access to learning that continue to

disadvantage some students.

• Students who experience very high socioeconomic vulnerabilities are less likely to be

assessed at the Provincial Standard of Level 3 or 4 in Academic English. This

disproportionate outcome has increased during the last three years.

Human Rights and Equity:

• Suspensions are disproportionate for African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous

students despite decrease in overall suspensions. While there is a reduction in the

number of suspensions in 2021-22 compared to 2018-19, African, Black, and Afro-

Caribbean and Indigenous students continue to be more than two-times more likely to be

suspended

• Students with special education needs experience barriers to learning. Students who

have an IEP are more than three times more likely to be suspended. Students identified

with an exceptionality that does not require a medical doctor diagnosis (Behavioural,

4

Language Impairment, Learning Disability, Mild Intellectual Disability), and therefore is

more subjective, are even more likely to receive a suspension.

Mental Health and Well-Being:

• Absenteeism is almost twice as high among some marginalized groups. African, Black,

and Afro-Caribbean, Indigenous, Latinx/Hispanic and Middle Eastern students

experience higher instances of absenteeism compared to other students, suggesting

that schools may not be places where they feel safe and/or offer a sense of belonging.

(Curry-Stevens & Kim-Gervey, 2016).

• Socioeconomic Vulnerabilities are a significant factor in students’ attendance outcomes.

Students with high SVI have been absent at a much higher rate consistently over the

years indicating that students who experience these vulnerabilities may not find learning

environments accessible, safe or conducive to their learning (Van Eck et al., 2017).

• Gender Diverse students are consistently more likely to be absent compared to those

who identify as male or female. While there has been parity for boys and girls over the

last 4 school years, students who identify with a diverse gender experienced much

higher instances of absenteeism, with an important decline in the 2020-21 when schools

were primarily online, suggesting that in-person school environments may not be places

where they feel safe and/or a sense of belonging (Pampati et al., 2020).

Pathways and Transitions:

• Students who identify as Indigenous, African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean, and White are

most likely to be identified with an exceptionality. African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean

students are about four times more likely to be identified with a behavioural

exceptionality and are one and a half to three times more likely to be identified with

language impairment, learning disability and mild intellectual disability. Indigenous

students are about four to five times more likely to be identified with the following

exceptionalities – autism, language impairment and, learning disability; they are also two

times more likely to be identified with a mild intellectual disability exceptionality.

• Students experiencing very low socioeconomic vulnerabilities (SVI) are two and a half

times more likely to be identified as gifted compared to students with higher SVI

suggesting that gifted assessments privilege those with access to more resources

(Parekh, et al., 2018).

• With the discontinuation of Applied programming in Grade 9, a higher proportion of

students are accessing Academic (de-streamed) programs which can lead to university

level courses. However, reviewing the outcomes, we see that African, Black, and Afro-

Caribbean students, Indigenous, Latinx/Hispanic, those with a very high SVI and those

with an IEP are still disproportionately streamed out of these opportunities.

• Some marginalized groups are underrepresented in university pathways in grade 12.

African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean students, along with Indigenous and Latinx/Hispanic

students, those experiencing very high and high socioeconomic vulnerabilities, and

students with Diverse Gender Identities, are disproportionately underrepresented in

university track pathways compared to others.

• African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean, Indigenous, Latinx/Hispanic, Middle Eastern, and

Southeast Asian students are underrepresented in Regional Learning Choice Programs

(RLCP). African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean students are severely underrepresented in

AP, IB, Business, Science and Technology programs. However, African, Black, and

5

Afro-Caribbean students are overrepresented in sports programs which may stem from

the harmful stereotype that associate Black children and youth with physical prowess

and superior athletic abilities further eroding their access to academic success (James &

Turner, 2017). Indigenous students are also severely underrepresented in all programs

with the exception of the Arts and AP programs.

Emerging Trends

• Online learning may have had varying impact on learners of different racial backgrounds.

African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean students across most grade levels consistently show

less credit accumulation in more recent years, suggesting they may have experienced

more impact by the disrupted schooling during COVID-19 closures. Similar patterns are

observed for students who identified with an additional racial background or as having

multiple racial backgrounds.

• COVID-19 impact is more severe on students experiencing socioeconomic

vulnerabilities. Credit accumulation gaps for students who experience very high

socioeconomic vulnerabilities have increased over the last three years, particularly for

students in Grade 10. This suggests that COVID-19 may have further exacerbated the

barriers experienced by these students.

• COVID-19 may have affected some students’ academic achievements more than others:

Students who identify as African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean are less likely to be

assessed at Level 3 and 4 in grade 9 and 10 Academic English in comparison to their

pre-COVID-19 learning (2018-19), suggesting that the barriers they are experiencing

have remained and worsened.

• Students with an IEP are more likely to be persistently absent than students without an

IEP. Though absenteeism has continued to remain much higher among students with

an IEP than students without an IEP, the pandemic may have negatively contributed to

their experiences as they have consistently experienced higher instances of

absenteeism, compared to pre-COVID-19, when learning was in-person. In the 2021-22

school year, they continued to be absent much more frequently, suggesting that the

limited availability of support for students with an IEP during remote learning (Rolland,

2020) may have also been a barrier for Peel students, for whom virtual classes were

spaces not conducive to their learning needs.

• Despite, the boards’ self-identification process for regional learning choice programs that

began in the 2020-2021 school year to address disproportionalities, there continues to

be disproportionate involvement for African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous

students. Unfortunately, the change in admissions process will likely take several years

to be reflected in the data as the nature of RLCPs having one-time entry will mean that

past inequities in admissions will persist in enrolment numbers. However, there is a

slight increase in African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean students participating in the Arts

programs.

6

Impact Analysis

Equity & Human Rights Review:

This report affirms the need for continued system change and transformation to ensure that

African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean, Indigenous, and other students who have been

marginalized and underserved because of systemic inequities have access to the high-quality

education and experiences they are entitled to under Human Rights and the Education Act (e.g.,

Culturally Responsive and Relevant pedagogy and resources; Universal Design for Learning

that for instance promotes student voice, agency, ownership and equitable assessment).

Board or Ministry Policy Alignment:

This report identifies that African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean, Indigenous and other racialized

students, students who identify with a diverse gender, 2SLGBQA+ students, students who

receive special education or additional English language supports continue to face systemic

inequities in achievement as summarized in the Ministry Review of the Peel District School

Board. The data presented is aligned with the requirements of Ministry Directive 9 to: i) report

on clearly defined student-centered outcomes including eliminating disparities in achievement of

students from the Board’s various communities (Chadha et el., 2020).

Resource Implications:

The trends presented of African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean, Indigenous and other racialized

students, students who identify with a diverse gender, 2SLGBQA+ students, students who

receive special education or additional English language supports require continued attention.

Continued inquiry into the intersecting relationships between achievement and schooling

experiences, race, and gender is necessary to inform future efforts towards system

transformation and sustainability of the necessary changes.

Legal implications:

The Peel District School Board has a duty to uphold each student’s human rights and create an

education system free from discrimination. The legal framework for the report card is in

accordance with the Ontario Education Act and the Ontario Human Rights Code.

Risk Assessment:

The Peel District School Board has been provided a strong mandate through the Ministry

Review to address disproportionate outcomes for African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean,

Indigenous and other students who have been historically marginalized. As stated in the

Ministry Review, “The task for those leaders is to bend best efforts of our education systems

into effective service for all” (p.36). As an organization, we must remain steadfastly focused on

ensuring that all PDSB students can realize their full potential in classrooms and schools where

they are supported, respected, valued, and welcomed (Chadha et al., 2020, p. 2). The students

and families in Peel have a right to a high-quality education. As a Board we have a moral and

ethical obligation to address and eliminate disproportionate outcomes for African, Black and

Afro-Caribbean, Indigenous and other students who have been historically marginalized.

7

Next Steps

Action Required:

• The content of this annual Equity Accountability Report Card (EARC) will be used by all

stakeholders to monitor change over time as well as identify areas for improvement. The

Research and Accountability team will work directly with each department and steering

committee to support the interpretation and use of this report. Specifically, it will be used

to inform:

o the monitoring of the Board Improvement and Equity Plan (Fall 2022),

o the development of future Board Improvement and Equity Plan foci (2022-23),

o goal setting and action planning for individual School Improvement and Equity

Plans (Fall 2022),

o the development of department goals and strategic actions (Fall 2022),

o the development of professional learning based on areas requiring additional

supports (2022-23)

o the development of the anti-Islamophobia Strategy (2022-23 school year), and

o the monitoring of the Black Student Success Strategy (Fall 2022).

• To ensure the ongoing development and reporting of disaggregated outcomes in the

Annual Equity Accountability Report Card, the following will be completed:

o the Peel DSB Identity-Data Collection Policy (Winter 2023), and

o a new student census will be conducted in Spring of 2023.

• Additionally, this report will be used to support ongoing work throughout the 2022-23

school year. For example, it will be used to:

o promote a culture of transparency and accountability for actions taken at system,

school, and classroom levels,

o inform policy review and development, and

o guide educators and leaders to interrogate biases and structures rooted in white

supremacy and promote action for anti-oppressive practices including strategies

to work with community.

• The next annual Equity Accountability Report Card will be produced in the Fall of 2023.

Success Measures:

Success Criteria:

• Completion of the Identity-Based Data Collection Policy,

• Completion of the next Student Census in Spring 2023,

• Evidence of a wide range of stakeholders (e.g., system leaders, school leaders,

community members) using the report to inform PDSB’s next steps,

• Evidence of the EARC providing value and usability for stakeholders,

• Collecting and using feedback to improve the report over time.

8

Measurement tools:

• Tracking the number of department and steering committee meetings the Research &

Accountability Team attend to support groups in the use of the EARC

• Tracking the number of times this report is accessed through the www.peelschools.org

and intranet sites.

• Feedback gathered from stakeholders on the value, usability, and suggested changes or

additions of the Equity Accountability Report Card.

• The development and implementation of a professional learning strategy based on this

report.

9

References:

Chadha, E., Herbert, S., & Richard, S. (2020). Review of the Peel District School Board. Ontario

Ministry of Education. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/new/review-peel-

district-school-board-report-en.pdf

Curry-Stevens, A., Kim-Gervey, C., & Chief Education Office Research Team. (2016). Chronic

absenteeism report.

James, C. E., & Turner, T. (2017). Towards race equity in education: The schooling of Black

students in the Greater Toronto Area. Toronto, ON: York University. Retrieved from

https://edu.yorku.ca/files/2017/04/Towards-Race-Equityin-Education-April-2017.pdf

Pampati, S., Andrzejewski, J., Sheremenko, G., Johns, M., Lesesne, C. A., & Rasberry, C. N.

(2020). School climate among transgender high school students: An exploration of

school connectedness, perceived safety, bullying, and absenteeism. The Journal of

School Nursing, 36(4), 293-303.

Parekh, G., Brown, R. S., & Robson, K. (2018). The social construction of giftedness: The

intersectional relationship between whiteness, economic privilege, and the identification

of gifted. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 7(2), 1-32.

Robson, K., Anisef, P., & Brown, R. (2016). “Identifying the complexity of barriers faced by

marginalized youth in transition to postsecondary education in Ontario”, in Wolfgang

Lehmann (Ed), Education and Society: Canadian Perspectives. London: Oxford

University Press, 2016.

Rolland, K.M. (2020). COVID-19, “learn at home,” & students with disabilities in Ontario.

International Human Rights Internship Program, Working Paper Series, 9(1), 1-40

Ryan, J. (1998). Understanding racial/ethnic stereotyping in schools: from image to discourse.

Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 44(3), 284-301.

Van Eck, K., Johnson, S. R., Bettencourt, A., & Johnson, S. L. (2017). How school climate

relates to chronic absence: A multi–level latent profile analysis. Journal of School

Psychology, 61, 89-102.

10

Appendices

EARC Report – Fall 2022

1

Annual Equity Accountability Report Card:

Looking at trends over time from 2018-19 to 2021-22 of Equity Gaps in Student Outcomes

October 2022

Research & Accountability

putting research into practice

2

1.0 Introduction

Following the release of the Ministry of Education Review of the Peel District School Board (PDSB) (Chadha et al., 2020)

in March 2020, the PDSB has been undertaking system transformation to ensure that the well documented and

historical inequities in student achievement and experiences are interrupted and eliminated. The PDSB recognizes that

in order to achieve our stated mission, which is to inspire success, confidence, and hope in every student, we must

identify and address the systemic inequities that persist today for students with particular identities and intersectional

identities, most notably students who identify as African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean, and/or Indigenous.

1.1 History of the Ministry Review

The Ministry Review of the PDSB was announced on November 7, 2019, by Ontario Minister of Education Stephen Lecce

and was conducted by three independent reviewers: Ena Chadha, Suzanne Herbert, and Shawn Richard, under the

leadership of Patrick Case. The mandate of the reviewers, under the authority of the Education Act, was to provide

observations and recommendations to the Minister of Education and the Peel District School Board related to the

performance of the Board, including, but not limited to issues of systemic discrimination, specifically anti-Black racism,

human resources practices, leadership, and board governance. These specific issues were investigated as a result of

serious concerns that had been raised repeatedly by parents and members of the African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean

communities. After consultations with students, staff, families, trustees, and community members, the Ministry of

Education released its final review report in March 2020 (Chadha et al., 2020).

The report addressed each of the

identified areas and contained a series of 27 binding directives with over 54 associated actions.

1.2 Ministry Directives and Action Items

The directives (Ministry of Education Ontario, 2020) outlined in the Ministry Review build on the longstanding work of

African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean parents, families, and communities in creating a truly excellent and equitable public

education system. The PDSB is committed to fulfilling these directives through anti-oppression and anti-racism

approaches. Disproportionalities in student engagement, experiences, and outcomes are recognized to be a result of

system policies, programs, and practices that stem from the “historic and systemic nature of anti-Black racism

embedded in Canadian society and institutions – including Ontario’s education system” (James & Turner, 2017, p. 39).

One of the key themes evident in the directives is the importance of monitoring, transparency, and accountability.

Directive 9 specifically instructs the Board to develop and implement a comprehensive Annual Equity Accountability

Report Card. The Annual Equity Accountability Report Card is intended to inform the Board’s efforts to create deep

structural and cultural changes that infuse the core values of equity, inclusion, and human rights into everyday practices,

programs, and policies. The report card is intended to assess and measure the implementation of the directives that

specifically address student outcomes. The One-Year Peel Board Community Update (PDSB, 2021)

provides further

progress information on the full set of directives.

1.3 Conceptual Framework

The data presented in this report is interpreted through the lens of Critical Race Theory (CRT). By centralizing the lived

experiences and realities of racialized individuals and communities, CRT has become an important tool to speak to the

pervasiveness of racism within education and educational institutions (James, 2012),

and against the monolithic ways in

which Indigenous, African, Black, Afro-Caribbean and racialized people(s) are often depicted, imagined, and stereotyped

(Ladson-Billings, 1998).

CRT generates narratives that counter hegemonic, problematic, and often racist ideologies

(James, 2009).

CRT challenges traditional dominant narratives around race, racism and the experiences of racialized people and

communities (Solórzano, D. G., & Yosso, 2002) and enables new and different questions to be asked about race and

racism in public education (Howard, 2008).

The practice of counter-storytelling is commonly utilized, in which stories

about discrimination from the perspectives of racialized individuals are presented to challenge the dominant narratives

of white supremacy that are sustained by deficit views of historically marginalized groups (James, 2012).

These

3

counternarratives recognize the agency that racialized individuals exercise to resist oppressive practices and offer

transformative solutions to eliminate racial inequities (James, 2012).

1.4 Anti-Black Racism and Education

According to the Ministry Review, “anti-Black racism [in Canada] must be placed in its historical context of slavery and

discrimination, including segregation, against Canada’s Black communities” (Chadha et al., 2020, p. 7).

The experiences

of African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean students in Peel are known to be heavily influenced by factors such as racial

separation, low academic expectations, stereotyping and stigma, and racial profiling (Gray et al., 2016).

African, Black,

and Afro-Caribbean youth in Peel schools have repeatedly reported dealing with low expectations of teachers and

administrators, assumptions based on racist stereotypes around their intellectual abilities and commitments to their

education, feelings of exclusion and marginalization from schools, and harsher discipline when compared to white

students (James, 2019a; James & Turner, 2015).

African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean students who attain high grades despite many difficulties are often met with surprise

and disbelief from non-Black students and teachers about their academic achievement. It is through the support of

family members, friends, some teachers, and extracurricular activities that these students are able to emotionally

navigate school (Gray et al., 2016).

Dealing with racism can lead African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean youth to suffer

through depression and issues related to low-self-esteem (James & Turner, 2015).

As it stands, the students entering our

classrooms are consistently navigating and making sense of racism, leading some students to become numb due to the

lack of support, or teachers not believing them when they report racist incidents (James, 2019b).

1.5 Anti-Indigenous Racism and Educational Outcomes

For Indigenous peoples of Canada, the education system has been one that actively enabled and engaged in systemic

discrimination against them since the early 1600s. Beginning with the establishment of the first school for Indigenous

youth in 1620, until the 1900s, the school system “tethered to the erasure of Indigenous culture, language and genocide

of communities” by forcing religious conversions and standardizing the removal of children from their families (Sekaly &

Bazzi, 2021, p. 4).

Between mid-1800s to 1970s, over 150,000 Indigenous children were forcibly separated from their families as part of

Canada’s assimilation policy. This deprived Indigenous children of not only their language and identity, but also

subjected them to poor living conditions and systemic abuse that continue to have negative effects on their mental,

physical, and social well-being (Han, 2021).

In Ontario, it has been noted that despite the government’s efforts to recognize past wrongs and to support Indigenous

learners, policies continue to promote a hidden curriculum that is rooted in colonialism, racism, and cultural/linguistic

imperialism (Currie-Patterson and Watson, 2017).

This approach enables the ongoing exclusion of Indigenous

knowledges from mainstream education, and thus deprives both students and teachers of opportunities to address the

ways in which education continues to colonize and hurt them. Moreover, the negative effects of past experiences are

evident in the ongoing disparities in achievement for Indigenous students. Some of the academic barriers Indigenous

communities experience include lack of educational funding that is in line with Indigenous communities’ needs and

identities (Sekaly & Bazzi, 2021),

the curriculum which remains outdated and biased (Han, 2021), and contrary efforts in

government-led initiatives. This includes the Ontario First Nation, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Framework, which

advocates for the inclusion of Indigenous culture in the curriculum but makes it difficult to do so due to the focus on

large scale provincial testing, a measurement tool that reflects Eurocentric values, and thus further marginalizes

Indigenous students (Currie-Patterson & Watson, 2017).

1.6 Intersections of Race, Education, and COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a disproportionate health impact on Black and other racialized families across North

America. Large concentrated urban areas, particularly neighbourhoods that report having the most ethno-culturally

diverse individuals and families in Ontario, have experienced rates of COVID-19 that are disproportionately higher than

4

neighborhoods that are less diverse (Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion, 2020). Racial categories that

are overrepresented in COVID-19 cases when compared to other racial categories within the Peel population are South

Asian, African, Black & Afro-Caribbean and Latinx/Hispanic (Region of Peel, 2020, August). In addition to its health

impacts, COVID-19 has served to exacerbate pre-existing educational inequities of Black and other marginalized

students, particularly in terms of nutrition, academic supports, mental health, and online learning (James, 2020).

2.0 How to Use this Report

The Peel District School Board is committed to improving student achievement and well-being by working to ensure

equitable, accessible, and inclusive learning environments. The Board recognizes that some students face systemic

barriers through policies, programs and practices that create or maintain disadvantages for these students. Ensuring

equitable, accessible, and inclusive learning environments, therefore, requires the intentional identification and removal

of systemic barriers to student success and well-being.

2.1 Engaging with these Data

This report outlines findings that point to disproportionalities in student experiences and outcomes based on socio-

demographic characteristics such as race, gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic vulnerabilities, English

Language Learner (ELL) status, and Special Education Needs.

The PDSB recognizes that the disproportionalities across demographics are the result

of inequities within and beyond schools and school boards

and are not a reflection of deficits within students and families

As such, it is important to review findings in this report with the understanding that:

• biases must be examined to ensure that students, families and communities are not further marginalized or

stigmatized in reviewing and interpreting data;

• disparities in student experiences and outcomes reflect systemic inequities; and,

• responses to disparities in student outcomes must focus on strategies and initiatives to promote equitable

institutional structures and practices.

The following questions are intended to support readers in using an anti-oppression framework to review the findings

in this report:

• What do you notice about the data?

• What stands out for you?

• How does your social location influence how you interpret the data?

• How will you shift or maintain your focus on looking at systems and structures (e.g., school practices, school

environment, Board practices) rather than attributing students’ experiences and outcomes to deficits within

students and families?

• What does the data suggest about the experiences of students and their families?

• What assumptions or inferences might you be making about students and their families based on the data?

• Whose voices may not be represented in the data?

• In what ways are the data similar to, or different from, other data sources (e.g., municipal, community

agencies, other school boards)?

• What additional data sources are needed to understand both complementary and divergent perspectives

regarding educational experiences?

5

2.2 Outcome Indicators

Credit Accumulation – Not on Track is represented by students who did not successfully complete 8 credits by the end

of Grade 9, 16 credits by end of Grade 10, 23 credits by end of Grade 11 and 30 credits by end of Grade 12.

English and Mathematics Academic/De-Streamed Report Card Outcomes. Is represented by students who did not

achieve Level 3 or 4 (provincial standard) in Grade 9 and 10 Academic English and Mathematics.

Regional Learning Choices Programs (RLCP) includes elementary and secondary students who were enrolled in a

Regional Learning Choices Programs. For information about which programs are included, please see the

corresponding elementary and secondary RLCP home pages found on our website, www.peelschools.org.

French Immersion/Extended French includes students enrolled in French Immersion and Extended French for

elementary and secondary students.

Pathways students take through school are complex and varied. This report reviews access to programs such as special

education services, Regional Learning Choice Programs and French Immersion. It also looks at the secondary course

pathways students take that impacts students’ access to post-secondary opportunities.

Students with Special Education Needs as an outcome indicator is reported on by each of the Ministry categories

(autism, behavioural, gifted, language impairment, learning disabilities, mild intellectual disability). Blind and Low

Vision, Deaf and Hard of Hearing, Developmental Disability, Physical, and Speech Impairment are not reported on

individually due to small numbers. Additionally, students who have an IEP without an IPRC, and Students receiving

Placement Services without an IEP or an IPRC is included as categories in this indicator

Suspensions represent elementary and secondary students who received at least one suspension.

Attendance – Persistent Absenteeism represents students who were absent for 15 or more instructional days in

the given school year.

Recent accounting of student perceptions of schooling are not available at this time. A climate/census survey is

planned for spring to gather data about students’ experiences in schools. Some of the topics to be covered are safe and

caring schools (including bullying, harassment, and discrimination), students’ well-being (e.g., sense of belonging),

inclusive experiences at school and students’ relationships with staff and peers.

2.3 Identity Factors

Data were coded by the following identity factors: racial background, gender identity, Socioeconomic Vulnerability Index

(SVI), Students with Special Education Needs, sexual orientation (grades 7-12), and English Language Learner (ELL)

status.

Indigenous and Racial Identity responses were coded into the following categories: African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean;

East Asian; First Nations, Métis, and Inuit; Latinx/Hispanic; Middle Eastern; South Asian; Southeast Asian; White;

Additional Racial Background (single responses only) and Did not Disclose (includes those that left the question blank,

and those that selected “prefer not to answer” and “do not know”). Multiple responses to this question were coded as

Multiple Racial Backgrounds. Note that the use of these specific categories is mandated by the Ontario Anti-Racism Data

Standards (Government of Ontario, 2019).

Gender Identity responses were coded into the following categories: Female, Male, Diverse Gender Identities (includes

Intersex, Questioning, Transgender, Multiple Gender Identities, Nonbinary, Gender fluid, Gender Nonconforming and

Additional Identities that were missed in the student census and Did Not Disclose (includes those who left the question

blank and those who selected “Prefer not to Answer” and “I am not sure what this question is asking”). Gender has

historically been a variable of considerable interest in educational research, and its relationship to academic

6

achievement, especially Math and Science, has been studied for decades (Meinck & Brese, 2019; Voyer & Voyer, 2014)

.

However, only relatively recently have scholars stopped treating gender identity as a dichotomous variable and started

to include gender diverse and gender nonconforming categories into the studies of academic achievement and student

well-being (Glavinic, 2010; Klemmer et al., 2019; Poteat et al., 2014; Selkie, 2018).

Sexual Orientation (Grades 7-12) responses were coded into the following categories: Heterosexual/straight,

2SLGBQA+ (includes Asexual, Bisexual, Gay, Lesbian, Pansexual, Queer, Questioning, Two spirit, multiple sexual

orientations and other sexual orientation) and Did not Disclose (includes those who left the question blank and those

who selected “prefer not to answer,” “do not know” and “I am not sure what this question is asking”). The acronym

2SLGBQA+ does not include T for Transgender nor I for Intersex as these identities are included in Gender Identity. This

variable is included in the report given well documented research indicating that 2SLGBQA+ students are more likely to

face inequalities, experience discrimination, victimization, and bullying, report a lower sense of well-being and

experience a higher prevalence of mental health issues when compared to their heterosexual peers (Poteat et al., 2014;

Friedman & Leaper, 2010; Williams, 2017; Woodford & Kulick, 2014).

This may in turn impact their overall well-being and

academic achievement (Kosciw et al., 2013).

Socioeconomic Vulnerability Index (SVI)

is a measure that provides the socioeconomic context of PDSB students

(Napierala et al. 2019). The variables used to calculate the index include median household income, percent living in

poverty (below $40,000), percent homeowners, percent without a high school diploma and percent with a university

degree within the households of a postal code. SVI scores are grouped into 6 clusters: Very High SVI, High SVI, Somewhat

High SVI, Moderate SVI, Somewhat Low SVI and Low SVI. Very High SVI represents high vulnerability and therefore lower

socioeconomic status while Low SVI represents lower vulnerability and correlates with a higher socioeconomic status.

International educational research established that socioeconomic status is a strong predictor of academic achievement

as it contributes to students’ economic, cultural and social capital (Broer et al. 2019; Buchmann, 2002; Lee et al. 2019;

Perry & McConney, 2013).

Both family and school socioeconomic status have been associated with long-term students’

academic outcomes because children begin school on unequal terms and differences accumulate as they get older

(Broer et al, 2019; Lareau, 2011; Lee & Burkam, 2002).

Students with Special Education Needs may be categorized according to the following exceptionalities as specified in

the Education Act: behavioural, communicational, intellectual, physical and multiple. According to the Ministry of

Education, these categories of exceptionalities “are designed to address the wide range of conditions that may affect a

student’s ability to learn and are meant to be inclusive of all medical conditions, whether diagnosed or not, that can lead

to particular types of learning difficulties” (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2017, p.A14). Students may have one

exceptionality or multiple exceptionalities. In this report card, “main exceptionality” refers to the first or only

exceptionality as listed within the Individual Education Plan.

When reporting Outcome Indicators by Students with Special Education Needs, students with an Individual Education

Plan (IEP) include both students with a formal identification through an Identification, Placement and Review Committee

(IPRC) and students without. Students with one identification of Gifted are excluded from this group.

English Language Learners (ELLs) are categorized as students “whose first language is a language other than English or is

a variety of English that is significantly different from the variety used for instruction in Ontario’s schools” (Ontario

Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 8). They may be enrolled in English Second Language (ESL) or English Literacy

Development (ELD) programs to help them attain the level of proficiency needed for completing schools in Ontario. ELL

students may be African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean, Indigenous, or racialized students. They may also include those

who have recently arrived from countries experiencing instability and crises or may be Canadian-born and come from

areas in Peel with high socioeconomic vulnerabilities.

7

2.4 How to Read the Graphs

This graph shows that students with a very high SVI in 2021-22 were more than two times likely than their

representation in the population to not accumulate 8 credits by the end of Grade 9.

2.5 Disproportionality Index

The Ontario Anti-Racism Data Standards defines a racial Disproportionality Index as “a measure of a racial group’s

overrepresentation or underrepresentation in a program, service, or function relative to the group’s representation in

the reference population” (Government of Ontario, 2019).

This report uses the Disproportionality Index to identify groups that are suspended disproportionately. These indicators

are calculated as follows:

Disproportionality Index =

% ℎ

% ℎ ℎ ℎ

2.6 Data Considerations

Trends over Time. Four years of outcomes are reported throughout this report: 2018-19, 2019-20, 2020-21, and

2021-22. In the spring of 2020, schools began to experience closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For the

2020-21 school year, much of the learning was conducted online, significantly impacting tracked data including

attendance measures and reducing in-person disciplinary events.

Access to Identity Data. The 2018 Student Census Data are used in this report to calculate the disproportionality

of experiences by social identity. Only students who participated in the 2018 survey are included in the analyses

disaggregated by these identities. There are no sexual orientation data available for students in Grade 9 in the

2021-22 school year as they were in Grade 6 at the time of survey administration and only Grade 7-12 students

were asked about sexual orientation. As each year passes since the Census was administered, the available

identity data about students decreases. For the 2021-22 school year, social identity data was available for 53%

of all PDSB students (43% of elementary and 76% of secondary students).

Students working towards an Ontario Secondary School Diploma (OSSD). Outcomes related to student

achievement and pathways (e.g., credit accumulation, achievement in English and Mathematics) only include

students who are working towards an OSSD.

Limitation of Disproportionality Index. When the category group size (e.g., students with a behavioural

identification) is small in comparison with the PDSB population, the Disproportionality Index size may become

unexpectedly large. To support interpretation in these cases, the y-axis has been limited to 6.0. The value

calculated is still represented in the graph but, visually, the bar has been limited to indicate disproportionate

experiences without limiting the interpretation of outcomes for other groups represented in the same graph.

8

Did not Disclose. Students who did not disclose their identity on the 2018 Census survey by leaving the question

blank or selecting responses of “I prefer not to answer”, “I don’t know” or “I am not sure what this question is

asking” were recoded into the variable “Did not disclose.” Outcomes across all measures for this group indicate

disproportionate school experiences which suggests that they likely identify with marginalized groups.

Suppression Rate. Groups of students smaller than 10 are not reported and are labeled N/R in an effort to

maintain student confidentiality and validity of the represented data. The value 10 is chosen as a balance

between transparent reporting and minimizing the use of outcomes that could be random rather than a

meaningful pattern.

Reporting Outcomes by Religion. Examining the outcomes in this report disaggregated by religion demonstrated

two consistent groups that experience disproportionate outcomes: students who indicated they were Christian

and those that did not affiliate with a religion. With further investigation it became apparent that there were

intersecting identities that better explained these outcomes. As a result, disaggregated outcomes by religion are

not included in this report.

2.7 Organization of Findings

The Board Improvement and Equity Plan, defined by the Ministry of Education, consists of four focus areas. Based on

outcomes identified in the first Annual Equity Accountability Report Card (PDSB, 2021), these focus areas have been

further refined as areas of work for the PDSB, particularly for students who identify as African, Black, and Afro-

Caribbean, Indigenous and students with Special Education Needs.

Student Achievement: Improved Literacy and Numeracy, and Credit Accumulation

Human Rights and Equity: Fair and just application of Exclusions, Suspensions and Expulsions

Mental Health and Well-Being: Increased Sense of Belonging

Pathways and Transitions: Increased access to pathway opportunities

3.0 Student Achievement

3.1 Credit Accumulation

3.1.1 Summary of Outcomes

Needs:

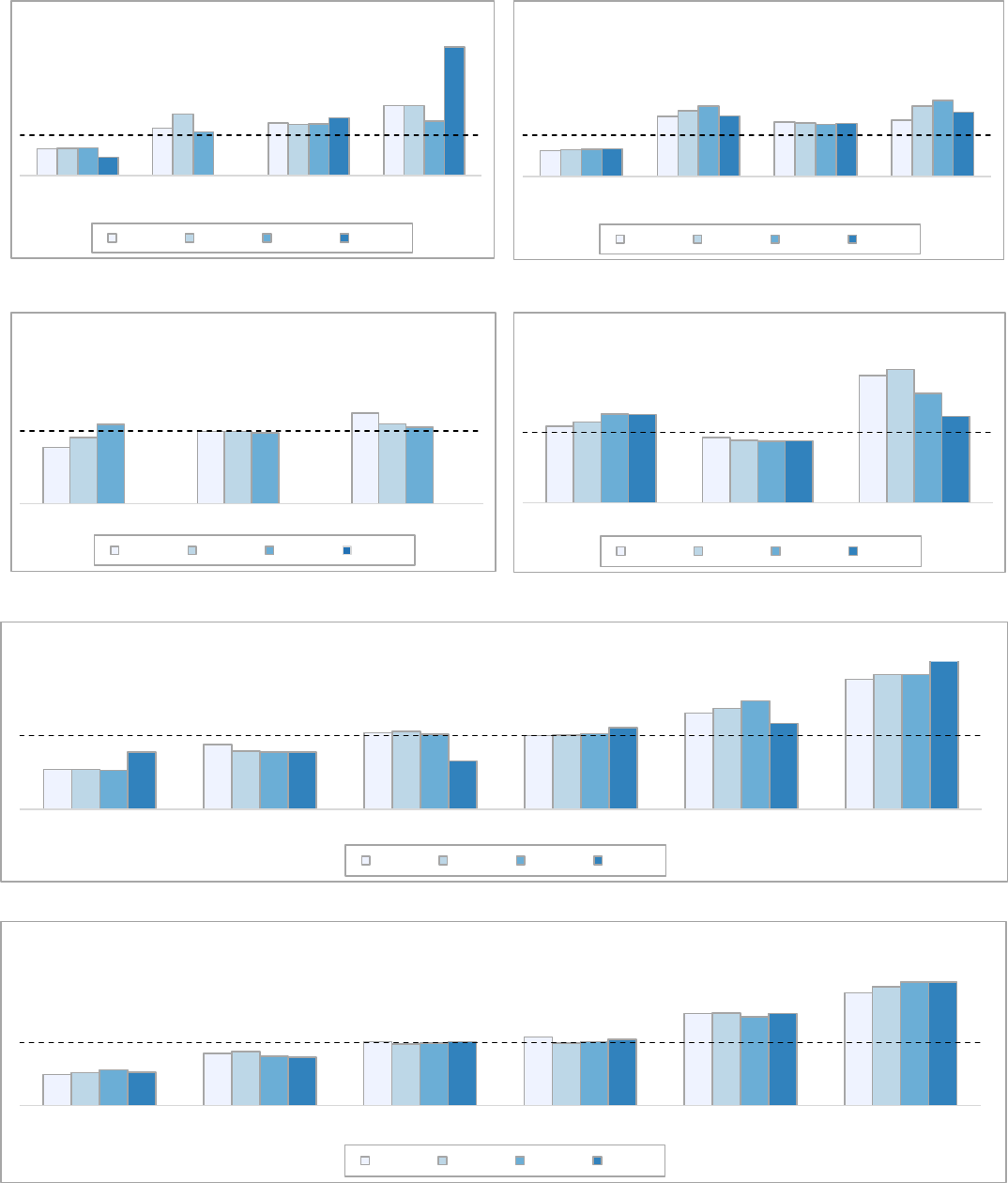

Consistent over-representation of identities that have been traditionally marginalized. African, Black, and

Afro-Caribbean, Indigenous, Latinx/Hispanic, Mixed Race and Middle Eastern students have not been granted

credits at the expected pace to graduate within four years. This trend is consistent across grade levels and

remains the same or increasing across years of study, suggesting that the barriers are still pervasive, and that

racism is an active factor (see Figure 1-4).

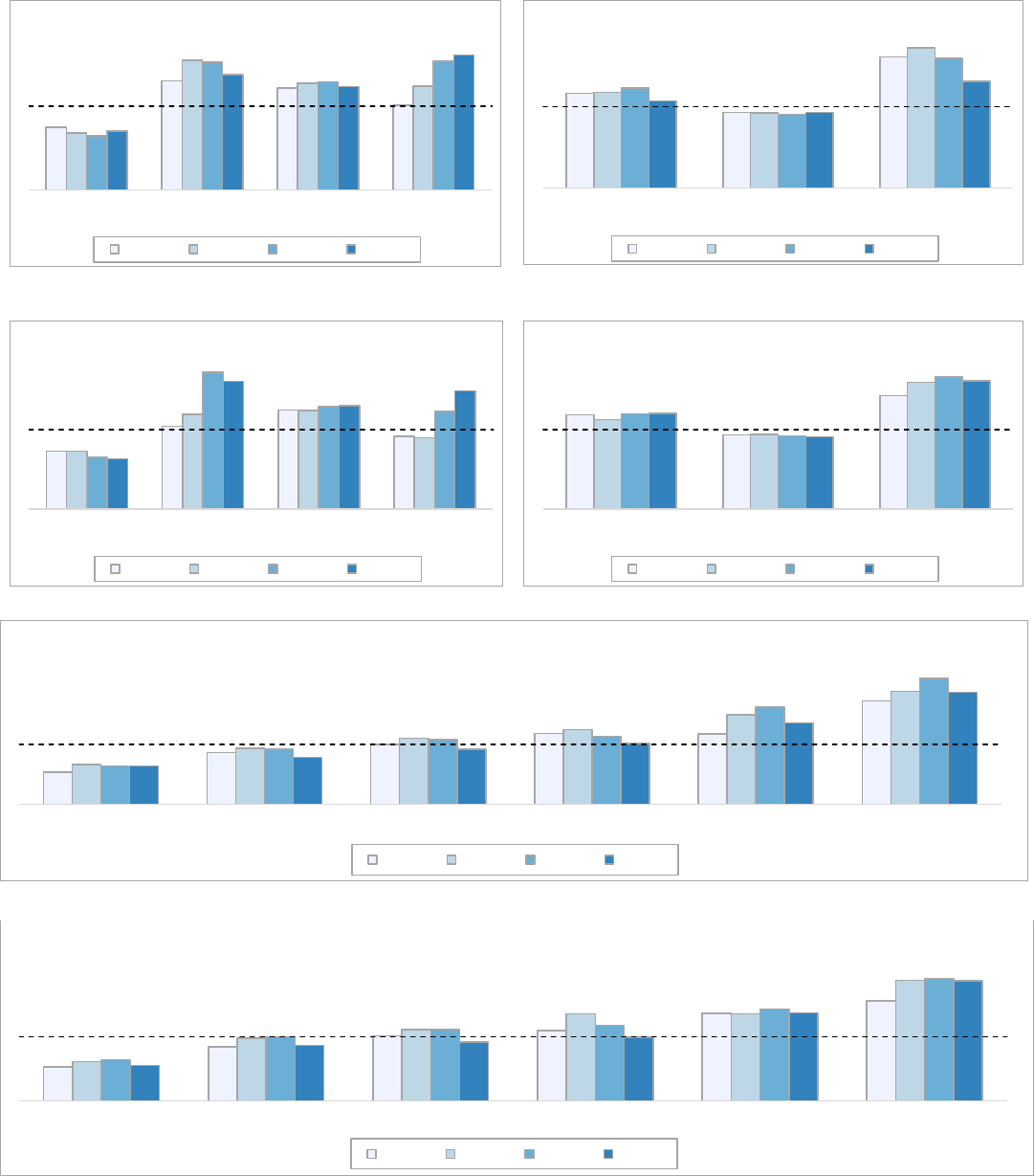

Diverse Gender identities continue to face greater barriers than girls or boys. Students who identified

themselves with a diverse gender identity and those who did not specify a gender continue to accumulate fewer

credits across all grades and years compared to those who only selected Male or Female suggesting that there

are ongoing systemic barriers towards their inclusion. This is not surprising as students who identify as a gender

other than male or female often face discrimination in larger society as well as within the education system

(Glavinic, 2010; Poteat et al., 2014) (see Figure 5-8).

Patriarchal Influences. There are significant gender differences as girls consistently outperform boys and those

with diverse gender identities when it comes to credit accumulation, affirming larger social trends; while boys

tend to accumulate less credits than girls, there are nonetheless potential signs that boys’ credit accumulation

may be improving over the school years (see Figure 5-8). These findings reveal the ongoing presence of a

gender gap in learning, often described as a result of various socio-cultural and economic factors influencing

boys’ daily life (Booth et al., 2009) as the consistency of the slower paced credit accumulation among boys both

9

across the grades and school years reveal that the problem may be systemic, and thus rooted in challenges

beyond simple accumulation of credits.

Low Credit Accumulation for 2SLGBQA+ students. Students who identify as 2SLGBQA+ face more barriers than

those identifying as heterosexual in accumulating credits. This aligns with larger societal trends that suggest that

schools reflect the experiences of non-marginalized groups (Currie et al., 2021), and that heterosexism (Statistics

Canada, 2019) is an ongoing barrier hindering educational progress. These barriers increase as the students get

older (see Figure 9-12).

Socioeconomic vulnerabilities are a significant barrier to credit accumulation. Across almost all grades and

school years, students who experience very high economic vulnerabilities accumulate fewer credits. This trend

also reinforces the idea that classism is a barrier to student success (Robson et al., 2016) (see Figure 13-16).

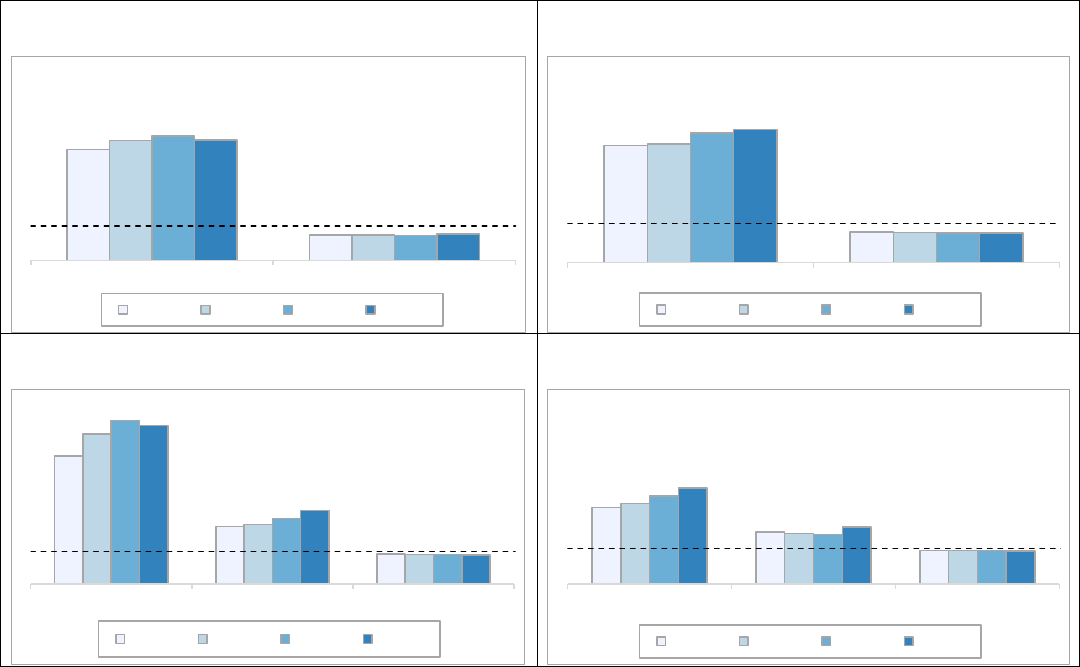

Students receiving Special Education Supports. Students with an IEP (identified and non-identified) are less

likely to accumulate credits at pace across all grades; however, this trend improves as students move up in grade

level. Additionally, Grade 9 students accumulated fewer credits in the last two years than the previous school

years suggesting that COVID-19 may have had an impact on students with Special Education Needs facing more

barriers to their learning during this time (Gallagher-Mackay et al., 2021) (see Figure 17-20).

Low credit accumulation for English Language Learners (ELL). English Language Learners, particularly those

receiving ELD support, accumulated fewer credits than their non-ELL counterparts in Grades 9-12 (see Figure 21-

24).

Emerging trends:

Improvement in credit accumulation is evident for some racially marginalized groups. For instance, some

lessening of gaps over the years are evident in the data, including for African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean

students (more have reached the credit accumulation target in later grades compared to grades 9 or 10). This is

the same for Middle Eastern students over the years, though not across grades (see Figure 1-4).

Online learning may have had varying impact on learners of different racial backgrounds. African, Black, and

Afro-Caribbean students across most grade levels consistently show less credit accumulation in more recent

years, suggesting they may have experienced more impact by the disrupted schooling during COVID-19 school

closures. Similar patterns are observed for students who identified with an additional racial background or as

having multiple racial backgrounds (see Figure 1-4).

Improvement in credit accumulation is evident for some 2SLGBQA+ students. These outcomes might be

explained by alternate learning environments due to COVID-19. Compared to pre-school closures, it appears

that their credit accumulation may have improved across the years, with students accruing fewer credits prior to

the beginning of school closures than later when there was a hybrid learning model in place. This trend may

align with prior findings suggesting students who normally experience marginalization or bullying prefer online

learning over in-person environments (PDSB, 2021b) (see Figure 9-12).

COVID-19 impact is more severe on students experiencing socioeconomic vulnerabilities (SVI). Credit

accumulation gaps for students who experience very high SVI have increased over the last three years,

particularly for students in Grade 10. One reason for this might be that COVID-19 may have further exacerbated

the barriers experienced by these students (see Figure 13-16).

10

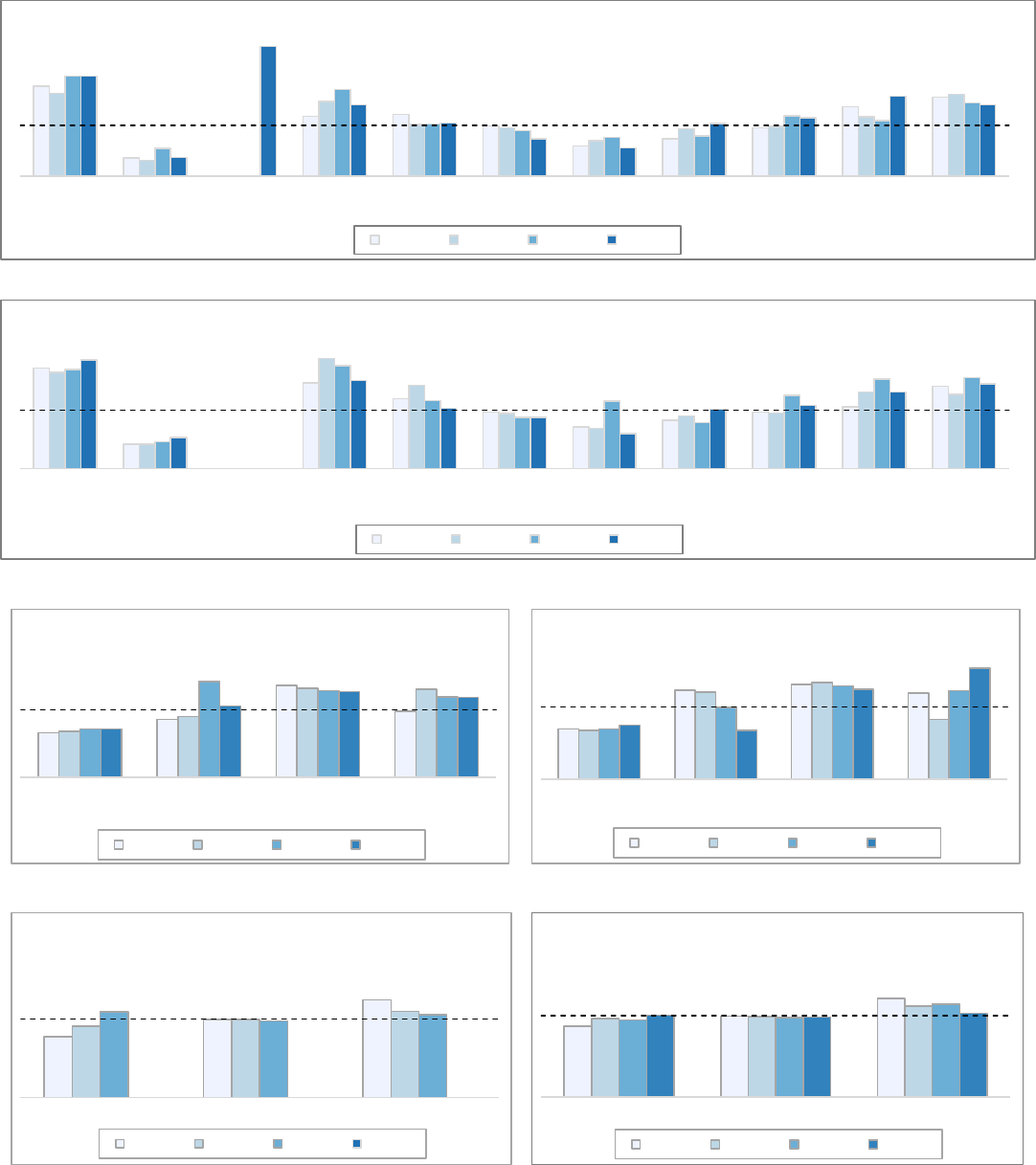

3.1.2 Indigenous and Racial Identities

Figure 1 - Students who did not Achieve 8 Credits by the End of Grade 9 by Indigenous and Racial Identity

Figure 2 - Students who did not Achieve 16 Credits by End of Grade 10 by Indigenous and Racial Identity

Figure 3 - Students who did not Achieve 23 Credits by End of Grade 11 by Indigenous and Racial Identity

Figure 4 - Students who did not Achieve 30 Credits by End of Grade 12 by Indigenous and Racial Identity

2.2

0.4

1.0

1.1

1.5

0.7

0.6

1.0

0.9

1.0

2.1

2.3

0.3

N/R

1.0

1.7

0.6

0.7

1.0

1.1

1.6

1.7

2.5

0.3

2.3

2.4

1.2

0.6

0.7

1.2

1.1

1.3

1.7

2.0

0.1

4.1

2.1

1.3

0.6

0.6

1.1

1.6

1.3

1.7

African,

Black &

Afro-Caribbean

East

Asian

First Nations,

Métis

and Inuit

Latinx/

Hispanic

Middle

Eastern

South

Asian

Southeast

Asian

White Additional

Racial

Background

Multiple

Racial

Backgrounds

Did not

disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.9

0.4

2.3

1.7

1.7

0.7

0.5

1.1

1.1

1.0

1.8

2.0

0.3

3.5

1.6

1.6

0.7

0.5

1.1

1.0

1.2

2.0

2.0

0.5

N/R

1.3

1.3

0.6

1.1

1.2

1.5

1.5

1.8

2.1

0.4

2.9

2.1

1.2

0.7

0.7

1.1

1.4

1.3

1.7

African,

Black &

Afro-

Caribbean

East

Asian

First Nations,

Métis

and Inuit

Latinx/

Hispanic

Middle

Eastern

South

Asian

Southeast

Asian

White Additional

Racial

Background

Multiple

Racial

Backgrounds

Did not

disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.7

0.5

4.4

1.4

1.5

0.7

1.1

0.9

0.8

1.2

1.9

1.8

0.5

1.0

1.4

1.8

0.7

0.4

1.1

0.9

1.1

1.7

2.0

0.4

2.8

2.7

1.6

0.6

0.7

1.1

1.0

1.3

1.8

2.0

0.4

N/R

1.2

1.4

0.6

1.0

1.2

1.5

1.6

1.7

African,

Black &

Afro-Caribbean

East

Asian

First Nations,

Métis

and Inuit

Latinx/

Hispanic

Middle

Eastern

South

Asian

Southeast

Asian

White Additional

Racial

Background

Multiple

Racial

Backgrounds

Did not

disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.6

1.1

1.6

2.1

0.7

1.8

0.9

0.5

1.2

1.1

1.5

0.7

5.4

1.5

1.7

0.7

1.2

1.0

1.0

1.2

2.1

1.8

0.6

2.8

2.0

2.0

0.5

0.8

1.3

0.8

1.1

1.6

1.7

0.5

2.9

1.9

1.8

0.6

0.8

1.2

1.2

1.4

1.8

African,

Black &

Afro-

Caribbean

East

Asian

First Nations,

Métis

and Inuit

Latinx/

Hispanic

Middle

Eastern

South

Asian

Southeast

Asian

White Additional

Racial

Background

Multiple

Racial

Backgrounds

Did not

disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

N/R

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

11

3.1.3 Gender Identity

Figure 5 - Students who did not Achieve 8 Credits by End of Grade 9

by Gender Identity

Figure 6 - Students who did not Achieve 16 Credits by End of Grade 10

by Gender Identity

Figure 7 - Students who did not Achieve 23 Credits by End of Grade 11

by Gender Identity

Figure 8 - Students who did not Achieve 30 Credits by End of Grade 12

by Gender Identity

3.1.4 Sexual Orientation (Grades 7-12)

Figure 9 - Students who did not Achieve 8 Credits by End of Grade 9

by Sexual Orientation

* Sexual orientation of Grade 9 students in 2021-22 is not available.

Figure 10 - Students who did not Achieve 16 Credits by End of Grade 10

by Sexual Orientation

Figure 11 - Students who did not Achieve 23 Credits by End of Grade

11 by Sexual Orientation

Figure 12 - Students who did not Achieve 30 Credits by End of Grade 12

by Sexual Orientation

0.8

1.7

1.2

2.0

0.8

3.0

1.2

1.9

0.8

1.8

1.2

2.0

0.9

2.9

1.1

1.6

Female Diverse Gender

Identity

Male Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

0.7

2.6

1.2

0.8

0.7

1.9

1.2

1.3

0.8

2.5

1.1

1.4

0.9

1.8

1.1

1.7

Female Diverse Gender

Identity

Male Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

0.7

1.6

1.2

1.2

0.7

3.1

1.2

0.8

0.7

2.1

1.2

1.4

0.8

1.6

1.2

1.6

Female Diverse Gender

Identity

Male Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

0.8

1.7

1.2

1.0

0.7

1.8

1.2

1.6

0.7

4.7

1.2

1.3

0.8

2.1

1.2

1.1

Female Diverse Gender

Identity

Male Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.3

0.9

2.1

1.2

0.9

1.0

1.1

1.0

1.4

N/A*

N/A

N/A

1

2SLGBQA+ Heterosexual/Straight Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.4

0.9

1.4

1.3

0.9

1.5

1.2

0.9

0.8

1.1

1.0

1.2

2SLGBQA+ Heterosexual/Straight Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.4

0.9

1.5

1.3

0.9

1.5

1.3

0.9

1.3

1.3

0.9

1.3

2SLGBQA+ Heterosexual/Straight Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.7

0.8

2.1

1.6

0.9

1.4

1.8

0.9

0.9

1.5

0.9

1.4

2SLGBQA+ Heterosexual/Straight Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

12

3.1.5 Socioeconomic Vulnerability Clusters

Figure 13 - Students who did not Achieve 8 Credits by End of Grade 9 by Socioeconomic Vulnerability Cluster

Figure 14 - Students who did not Achieve 16 Credits by End of Grade 10 by Socioeconomic Vulnerability Cluster

Figure 15 - Students who did not Achieve 23 Credits by End of Grade 11 by Socioeconomic Vulnerability Cluster

Figure 16 - Students who did not Achieve 30 Credits by End of Grade 12 by Socioeconomic Vulnerability Cluster

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.1

1.2

1.9

0.5

0.7

0.9

1.1

1.2

2.3

0.5

0.8

1.0

1.1

1.2

2.1

0.6

0.8

0.8

1.1

1.4

2.1

Low Somewhat Low Moderate Somewhat High High Very High

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.1

1.2

1.7

0.7

0.9

0.9

1.0

1.3

1.9

0.6

0.8

0.9

1.0

1.2

2.0

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.0

1.1

2.0

Low Somewhat Low Moderate Somewhat High High Very High

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1.2

2.0

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.1

1.4

1.7

0.5

0.8

1.0

0.9

1.3

2.0

0.6

0.8

0.9

0.9

1.2

2.0

Low Somewhat Low Moderate Somewhat High High Very High

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

0.8

0.9

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.8

0.7

0.9

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.8

0.8

0.8

0.9

1.1

1.3

1.8

0.6

0.8

0.9

1.0

1.3

1.9

Low Somewhat Low Moderate Somewhat High High Very High

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

13

3.1.6 Students with Special Education Needs

Figure 17 - Students who did not Achieve 8 Credits by End of Grade 9

by Individual Education Plan (IEP) Status

Figure 18 - Students who did not Achieve 16 Credits by End of Grade

10 by Individual Education Plan (IEP) Status

Figure 19 - Students who did not Achieve 23 Credits by End of Grade 11

by Individual Education Plan (IEP) Status

Figure 20 - Students who did not Achieve 30 Credits by End of Grade

12 by Individual Education Plan (IEP) Status

3.1.7 English Language Learners

Figure 21 - Students who did not Achieve 8 Credits by End of Grade 9 by

English Language Learner Status

Figure 22 - Students who did not Achieve 16 Credits by End of Grade

10 by English Language Learner Status

Figure 23 - Students who did not Achieve 23 Credits by End of Grade 11

by English Language Learner Status

Figure 24 - Students who did not Achieve 30 Credits by End of Grade

12 by English Language Learner Status

2.3

0.9

2.4

0.9

2.8

0.8

2.7

0.9

IEP No IEP

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

2.2

0.9

2.1

0.9

2.2

0.9

2.2

0.9

IEP No IEP

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.9

0.9

2.2

0.9

2.2

0.9

2.0

0.9

IEP No IEP

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.4

0.9

1.5

0.9

2.0

0.9

1.7

0.9

IEP No IEP

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

5.7

2.4

0.9

8.7

2.8

0.8

7.4

2.3

0.9

6.8

3.3

0.9

ELD ESL Not ELL

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

4.6

2.3

0.9

6.1

2.6

0.8

6.0

2.6

0.9

5.1

2.4

0.9

ELD ESL Not ELL

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

5.1

2.4

0.9

5.2

2.3

0.8

6.7

2.6

0.8

6.1

2.7

0.9

ELD ESL Not ELL

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

5.5

3.0

0.8

6.1

3.2

0.8

6.5

2.8

0.8

6.5

3.2

0.8

ELD ESL Not ELL

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

14

3.2 Grades 9 and 10 Literacy and Numeracy

3.2.1 Summary of Outcomes

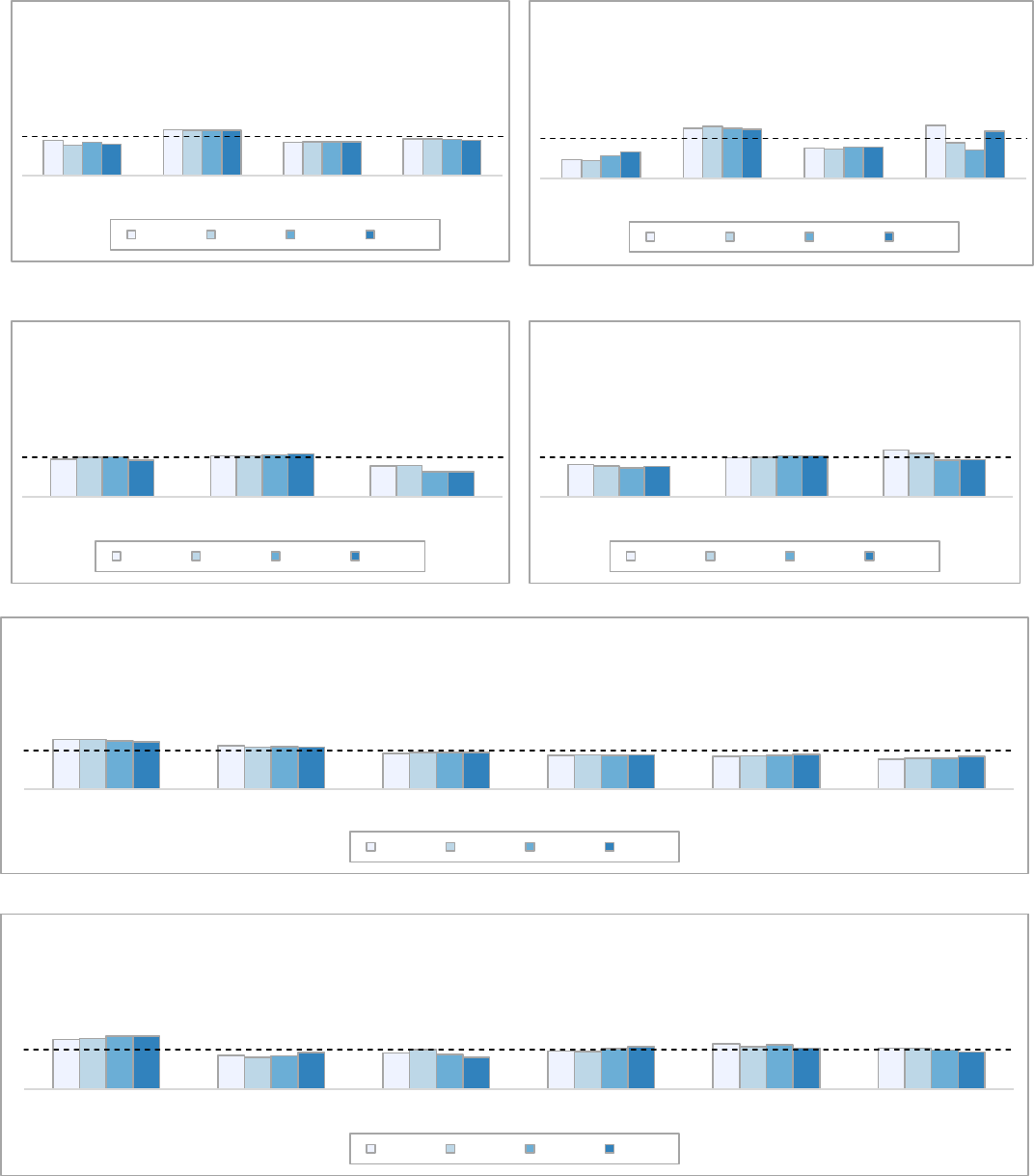

Needs:

Disproportionate Outcomes by Racial Background. African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean, Indigenous and

Latinx/Hispanic students are the most likely to be assessed below Levels 3 or 4 in Grade 9 and 10 Academic

English. These findings indicate that while de-streaming Grade 9 Mathematics and English courses may remove

some barriers, likely there are prior gaps in access to learning that continue to disadvantage some students (see

Figure 25-26 and Figure 37-38).

Literacy versus numeracy challenges. Students who identify as Latinx/Hispanic and Middle Eastern have higher

rates of disproportionate experiences in Grade 9 and 10 Academic English than Academic/de-streamed

Mathematics. These outcomes are also likely a result of gaps in prior access to learning (see Figure 25-26, and

Figure 37-38).

Students who identify with a diverse gender identity may be struggling in English and Mathematics. The

population sizes of these groups are relatively small when looking at grade-level outcomes so individual positive

or negative outcomes may have impacted the trends displayed in these graphs. Given the trends and

experiences of the larger population, assumptions can be made that these students are experiencing barriers to

their success (see Figure 27-28, and Figure 39-40).

Girls outperform boys in Literacy. Girls were consistently assessed at or above the Provincial Standard (Levels 3

or 4) more often than boys (see Figure 27-28, and Figure 39-40).

Socioeconomic vulnerabilities impact English learning. Students who experience very high socioeconomic

vulnerabilities are less likely to be assessed at the Provincial Standard of Level 3 or 4 in Academic English. This

disproportionate outcome has increased during the last three years (see Figure 31-32).

Students receiving Special Education Supports. Students who have an IEP and may or may not have a formal

identification are almost two times less likely to be assessed at or above the Provincial Standard in comparison

with students who do not have an IEP. This gap is more notable for Academic English outcomes (see Figure 33-

34, and Figure 45-46).

English Language Learners. ELLs are one and half to two times more likely to be assessed not at or above

Provincial Standard (Levels 3 or 4) in Academic English or Academic/De-streamed Mathematics compared to

non-ELLs (see Figure 35-36 and Figure 47-48).

Emerging Trends:

COVID-19 may have affected some students’ academic achievements more than others: Students who identify

as African, Black, and Afro-Caribbean are less likely to be assessed at Level 3 and 4 in grade 9 and 10 Academic

English in comparison to their pre-COVID-19 learning (2018-19), suggesting that the barriers they are

experiencing have remained and worsened (see Figure 25-26).

Slight improvement for boys in literacy. The disproportionate outcomes for boys in Grade 9 and 10 Academic

English appear to be decreasing (see Figure 27-28).

2SLGBQA+ Students doing well in literacy and numeracy. Trends suggest that students who identify as

2SLGBQA+ do as well as their heterosexual classmates (see Figure 29-30, and Figure 41-42).

Students with an IEP need support to be successful in de-streamed classes. Trends suggest that students who

have an IEP may need more support to achieve the Provincial Standard (Levels 3 or 4) in both grades 9 and 10

Academic/De-streamed English and Mathematics (see

Figure 33-34 and Figure 45-46).

15

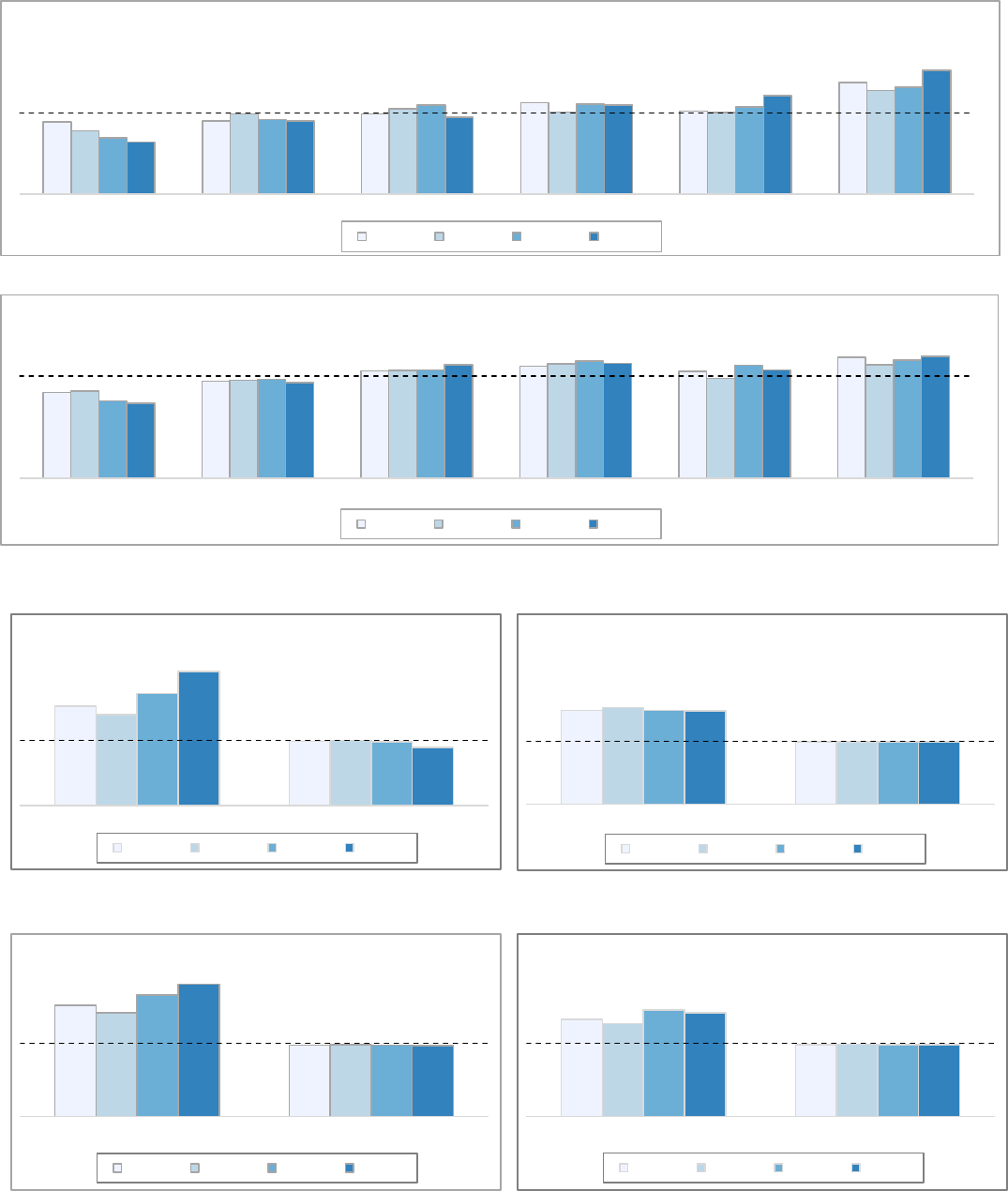

3.2.2 Literacy Outcomes

Figure 25 - Students in Grade 9 Academic English Not Achieving Level 3 or 4 by Indigenous and Racial Identities

Figure 26 - Students in Grade 10 Academic English Not Achieving Level 3 or 4 by Indigenous and Racial Identities

Figure 27 - Students in Grade 9 Academic English Not Achieving Level 3

or 4 by Gender Identity

Figure 28 - Students in Grade 10 Academic English Not Achieving Level

3 or 4 by Gender Identity

Figure 29 - Students in Grade 9 Academic English Not Achieving Level 3

or 4 by Sexual Orientation

* Sexual orientation of Grade 9 students in 2021-22 is not available.

Figure 30 - Students in Grade 10 Academic English Not Achieving Level

3 or 4 by Sexual Orientation

1.8

0.4

1.2

1.2

1.0

0.6

0.7

0.9

1.4

1.5

1.6

0.3

N/R

1.5

1.0

1.0

0.7

0.9

1.0

1.2

1.6

2.0

0.5

1.7

1.0

0.9

0.8

0.8

1.2

1.1

1.4

2.0

0.4

2.5

1.4

1.0

0.7

0.6

1.0

1.2

1.6

1.4

African,

Black &

Afro-Caribbean

East

Asian

First Nations,

Métis &

Inuit

Latinx/

Hispanic

Middle

Eastern

South

Asian

Southeast

Asian

White Multiple

Racial

Backgrounds

Additional

Racial

Background

Did not

disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.7

0.4

1.5

1.2

1.0

0.7

0.8

1.0

1.1

1.4

1.7

0.4

1.9

1.4

0.9

0.7

0.9

0.9

1.3

1.3

1.7

0.5

N/R

1.8

1.2

0.9

1.2

0.8

1.3

1.5

1.6

1.9

0.5

1.5

1.0

0.9

0.6

1.0

1.1

1.3

1.5

African,

Black &

Afro-

Caribbean

East

Asian

First Nations,

Métis &

Inuit

Latinx/

Hispanic

Middle

Eastern

South

Asian

Southeast

Asian

White Multiple

Racial

Backgrounds

Additional

Racial

Background

Did not

disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

0.7

0.9

1.4

1.0

0.7

0.9

1.3

1.3

0.7

1.4

1.3

1.2

0.7

1.1

1.3

1.2

Female Diverse gender

Identity

Male Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

0.7

1.2

1.3

1.2

0.7

1.2

1.3

0.8

0.7

1.0

1.3

1.2

0.7

0.7

1.2

1.5

Female Diverse Gender

Identity

Male Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

0.8

1.0

1.2

0.9

1.0

1.1

1.1

1.0

1.1

N\A*

N\A

N\A

2SLGBQA+ Heterosexual/Straight Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

0.9

1.0

1.2

1.0

1.0

1.1

0.9

1.0

1.1

1.0

1.0

1.0

2SLGBQA+ Heterosexual/Straight Did not disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above

1.0

16

Figure 31 - Students in Grade 9 Academic English Not Achieving Level 3 or 4 by Socioeconomic Vulnerability Cluster

Figure 32 - Students in Grade 10 Academic English Not Achieving Level 3 or 4 by Socioeconomic Vulnerability Cluster

Figure 33 - Students in Grade 9 Academic English Not Achieving Level

3 or 4 by IEP Status

Figure 34 - Students in Grade 10 Academic English Not Achieving Level 3

or 4 by Students with an IEP Status

Figure 35 - Students in Grade 9 Academic English Not Achieving Level

3 or 4 by ELL Status

Figure 36 - Students in Grade 10 Academic English Not Achieving

Level 3 or 4 by ELL Status

0.8

0.9

1.1

1.1

1.1

1.1

0.8

0.9

1.1

1.1

1.0

1.3

0.6

0.8

1.1

1.1

1.1

1.6

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.1

1.2

1.6

Low Somewhat Low Moderate Somewhat High High Very High

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

0.8

1.0

1.0

1.2

1.0

1.2

0.8

0.9

1.0

1.1

1.0

1.3

0.7

1.0

1.0

1.1

1.1

1.5

0.7

0.9

1.1

1.1

1.1

1.5

Low Somewhat Low Moderate Somewhat High High Very High

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.6

1.0

1.8

1.0

1.7

1.0

2.1

0.9

IEP No IEP

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.8

1.0

2.0

1.0

1.6

1.0

1.8

1.0

IEP No IEP

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.9

1.0

2.1

1.0

1.9

1.0

2.1

1.0

ELL Not ELL

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

2.0

1.0

1.7

1.0

2.0

1.0

2.3

1.0

ELL Not ELL

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

17

3.2.3 Numeracy Outcomes

Figure 37 - Students in Grade 9 Academic Mathematics Not Achieving Level 3 or 4 by Indigenous and Racial Identities

Figure 38 - Students in Grade 10 Academic Mathematics Not Achieving Level 3 or 4 by Indigenous and Racial Identities

Figure 39 - Students in Grade 9 Academic Mathematics Not Achieving

Level 3 or 4 by Gender Identity

Figure 40 - Students in Grade 10 Academic Mathematics Not

Achieving Level 3 or 4 by Gender Identity

Figure 41 - Students in Grade 9 Academic Mathematics Not Achieving

Level 3 or 4 by Sexual Orientation

* Sexual orientation of Grade 9 students in 2021-22 is not available.

Figure 42 - Students in Grade 10 Academic Mathematics Not

Achieving Level 3 or 4 by Sexual Orientation

1.8

0.3

1.4

1.2

1.0

0.7

0.9

1.0

1.3

1.3

1.6

0.3

1.3

1.0

0.9

0.8

1.0

1.1

1.6

1.4

1.9

0.4

N/R

0.9

1.1

0.9

0.7

1.1

1.3

1.0

1.3

1.9

0.3

2.7

1.7

1.1

0.7

0.8

1.1

1.2

1.7

1.4

African,

Black &

Afro-

Caribbean

East

Asian

First Nations,

Métis &

Inuit

Latinx/

Hispanic

Middle

Eastern

South

Asian

Southeast

Asian

White Multiple

Racial

Backgrounds

Additional

Racial

Background

Did not

disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.6

0.3

1.4

1.1

1.0

0.6

1.0

1.1

1.2

1.4

1.6

0.3

1.5

1.0

1.0

0.7

1.0

1.0

1.3

1.2

1.9

0.3

N/R

1.3

1.0

0.9

0.8

0.9

1.2

1.4

1.4

1.8

0.4

0.8

1.2

0.9

0.5

0.9

1.1

1.3

1.4

African,

Black &

Afro-

Caribbean

East

Asian

First Nations,

Métis &

Inuit

Latinx/

Hispanic

Middle

Eastern

South

Asian

Southeast

Asian

White Multiple

Racial

Backgrounds

Additional

Racial

Background

Did not

disclose

2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

- - - - Disproportionate above 1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

0.8

0.9

0.9

1.1

0.9

0.9

1.5

1.1

1.5

0.9

1.8

1.0

1.2

Female Diverse gender