September 2017

AUTHORS

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad is Senior Fellow, Racial Wealth Divide at Prosperity Now. As Senior Fellow,

Dedrick’s responsibilities include strengthening Prosperity Now's outreach and partnership with

communities of color, as well as strengthening Prosperity Now's racial wealth divide analysis in its work.

Prosperity Now's Racial Wealth Divide Initiative also leads wealth-building projects that aim to establish

best practices and policy recommendations to address racial economic inequality. Prior to Prosperity Now,

Dedrick was Senior Director of the Economic Department and Executive Director of the Financial Freedom

Center at NAACP.

Chuck Collins is Director of the Program on Inequality at the Institute for Policy Studies, where he co-

edits Inequality.org. His most recent book is Born on Third Base: A One Percenter Makes the Case for

Tackling Inequality, Bringing Wealth Home and Committing to the Common Good (Chelsea Green, 2016).

He is co-author, with Bill Gates, Sr., of Wealth and Our Commonwealth: Why America Should Tax

Accumulated Fortunes. He is co-author with Mary Wright of The Moral Measure of the Economy (Orbis

2008), a book about Christian ethics and economic life. He is also the author of 99 to 1: How Wealth

Inequality is Wrecking the World and What We Can Do About It.

Josh Hoxie heads the Project on Opportunity and Taxation at the Institute for Policy Studies. He co-

authored multiple reports including Gilded Giving: Top-Heavy Philanthropy in an Age of Extreme Inequality,

The Ever-Growing Gap: Without Change, African-American and Latino Families Won't Match White Wealth

for Centuries and Billionaire Bonanza: The Forbes 400 and the Rest of Us. He has written widely on income

and wealth maldistribution for Inequality.org and other media outlets. He worked previously as a

legislative aide for U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT).

Emanuel Nieves is Senior Policy Manager at Prosperity Now, where he works to inform and mobilize

advocates across the country to push for policy change at the federal level that expands economic

opportunity. He also leads Prosperity Now's work on predatory lending and coordinates the Asset Building

Policy Network. Before joining Prosperity Now, he worked at Local Initiatives Support Corporation, where

he coordinated LISC’s local office advocacy efforts in Washington, DC, and provided support on an array of

housing and community development federal issues.

The authors thank current and former Prosperity Now staff and consultants—Ana Maria Argudo-Lord, Roberto

Arjona, Sandiel Grant, Jeremie Greer, Merrit Gillard, Ezra Levin, Sean Luechtefeld, David Meni, David Newville, Amy Saltzman and

Lebaron Sims—for their invaluable contributions in the production of this report. We also thank Institute for Policy Studies staff—

Jessicah Pierre, Sarah Anderson, Sam Pizzigati, John Cavanagh, Domenica Ghanem and Kenneth Worles Jr.—for their thoughtful

contributions to the report. It should be noted that the authors listed were equal partners in the drafting of this report and have been

listed here alphabetically by last name.

The Institute for Policy Studies (IPS-dc.org) is a 54-year-old multi-issue research center that has conducted path-breaking research on

inequality for more than 20 years. The IPS’ inequality.org website provides an online portal into all things related to the income and

wealth gaps that so divide us in the United States and throughout the world.

Prosperity Now (formerly CFED; prosperitynow.org) believes that everyone deserves a chance to prosper. Since 1979, we have helped

make it possible for millions of people, especially people of color and those of limited incomes, to achieve financial security, stability

and, ultimately, prosperity. We offer a unique combination of scalable practical solutions, in-depth research and proven policy solutions,

all aimed at building wealth for those who need it most.

1112 16

th

Street NW

Suite 600

Washington, DC 20036

202.234.9382

ips-dc.org

Email:

1200 G Street NW

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20005

202.408.9788

prosperitynow.org

Email:

dasantemuhammad@prosperitynow.org

Press Contacts:

Amy Saltzman

asaltzman@thehatchergroup.com

301.656.0348

Sean Luechtefeld

sluechtefeld@prosperitynow.org

202.207.0143

© 2017 - Institute for Policy Studies & Prosperity Now

Key Findings

In our 2016 report, The Ever-Growing Gap: Without Change, African American and Latino Families Won’t Match White Wealth for

Centuries, we showed that it if current trends continue, it will take 228 years for the average Black family to reach the level of wealth

White families own today. For the average Latino family, matching the wealth of White families will take 84 years.

In this report, we look at the racial wealth divide at the median over the next four and eight years, as well as to 2043, when the

country’s population is predicted to become majority non-white. We also look to wealth rather than income to reconsider what it

means to be middle class. In finding an ever-accelerating gap, we consider what it means for the American middle class and we explore

what policy interventions could reverse the trends we see today. We find that without a serious change in course, the country is

heading towards a racial and economic apartheid state.

• Earning a middle-class income does not guarantee middle-class economic security. White households in the middle-income quintile

(those earning $37,201-$61,328 annually) own nearly eight times as much wealth ($86,100) as middle-income Black earners

($11,000) and ten times as much wealth as middle-income Latino earners ($8,600). This disconnect in income earned and wealth

owned is visible across the entire income spectrum between these groups.

• If the middle class were to be defined by wealth rather than by income, Black and Latino families in the middle-income quintile

would need to earn 2-3 times as much as White families in order to enter the middle class. If we were to define the middle class in

terms of wealth, households would need to own between $68,000-$204,000 in wealth to qualify for the middle class. Under these

terms, only Black and Latino households in the highest income-quintile (those earning more than $104,509) would qualify for

middle-class status or higher, compared to White households in the top three income-quintiles who already own wealth in excess

of this threshold. In fact, only Black and Latino households with an advanced degree have enough wealth to be considered middle-

class, whereas all White households with a high school diploma or higher would be considered middle class.

• Defining class in terms of wealth instead of income, roughly 70% of Black and Latino households would fall below the $68,000

threshold needed for middle-class status, whereas only about 40% of White households would fall below the middle class. In

contrast, roughly 13% of Black and Latino households could be considered to have “upper-wealth” (meaning they own at least

$204,000 in wealth), compared to 40% of White households.

• The accelerating decline in wealth over the past 30 years has left many Black and Latino families unable to reach the middle class.

Between 1983 and 2013, the wealth of median Black and Latino households decreased by 75% (from $6,800 to $1,700) and 50%

(from $4,000 to $2,000), respectively, while median White household wealth rose by 14% (from $102,200 to $116,800). If current

trends continue, by 2020 median Black and Latino households stand to lose nearly 18% and 12%, respectively, of the wealth they

held in 2013. In that same timeframe, median White household wealth would see an increase of 3%. Put differently, in just under

four years from now, median White households are projected to own 86 and 68 times more wealth than Black and Latino

households, respectively.

• By 2024, median Black and Latino households are projected to own 60-80% less wealth than they did in 1983. By then, the

continued rise in racial wealth inequality between median Black, Latino and White households is projected to lead White

households to own 99 and 75 times more wealth than their Black and Latino counterparts, respectively.

• If the racial wealth divide is left unaddressed and is not exacerbated further over the next eight years, median Black household

wealth is on a path to hit zero by 2053—about 10 years after it is projected that racial minorities will comprise the majority of the

nation’s population. Median Latino household wealth is projected to hit zero twenty years later, or by 2073. In sharp contrast,

median White household wealth would climb to $137,000 by 2053 and $147,000 by 2073.

• Change our nation’s tax code to stop subsidizing the already-wealthy and start investing in opportunities for low-wealth families to

build wealth. Specifically, reform the mortgage interest deduction and other tax expenditures, bolster and expand the federal

estate tax, and create a net-worth tax on multi-million-dollar fortunes.

• Protect low-wealth families from wealth-stripping practices by strengthening the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and closing

the nefarious offshore tax shelters currently enabling the ultra-wealthy to hide their assets.

• Invest in bold new programs like Children’s Savings Accounts, automatic-enrollment retirement accounts, federal jobs guarantees

and a racial wealth divide audit of government policies, all of which are vital to reducing the gap between the ultra-wealthy and the

rest of the country.

For several years, politicians, researchers, journalists and the public have focused their attention on growing economic inequality in the

United States. Most often, this focus is on income (i.e., the wages earned from a job or from capital gains) rather than on wealth (i.e.,

the sum of one’s assets minus their debts). Income inequality, while stark, pales in comparison to the vast economic divide exposed by

examining disparities in wealth. For example, a recent study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

found that while the top 10% of income earners in United States receive almost 30% of the nation’s income, the wealthiest 10% own an

astounding 76% of the country’s wealth. That means less than a quarter of the nation’s wealth is left for the bottom 90% of the

American population.

1

As stark and as overlooked as these disparities are, they are particularly acute along racial lines as a disproportionate share of the

nation’s wealth is held in White hands while households of color own a shrinking slice of the proverbial pie. Today, this translates into a

racial wealth divide in which the median net worth of Black and Latino families stands at just $11,000 and $14,000, respectively—a

fraction of the $134,000 owned by the median White family.

2

Even more disturbing is that when consumer durable goods such as

automobiles, electronics and furniture are subtracted, median wealth for Black and Latino families drops to $1,700 and $2,000,

respectively, compared to $116,800 for White households (see Methodology for more details).

While some argue that this racial wealth divide stems from choices made by individuals and communities, the facts tell a different story.

Recent research shows that the racial wealth divide persists across all levels of educational attainment and family structures, seriously

diminishing the “personal choices” argument. Case in point? White high school dropouts own more wealth than Black and Latino college

graduates.

3

Furthermore, single-parent White households own more wealth than two-parent Black households.

4

Wealth is the buffer families need when faced with unexpected economic shocks like a lost job or a broken-down car. Wealth is also the

capital available to families to take advantage of economic opportunities, like buying a home, saving for college or investing in the stock

market. Ultimately, wealth can be the difference between a family maintaining and strengthening their economic status or flailing in

economic insecurity.

Beyond these measures, wealth is also critically important to understanding the racial disparities in middle-class status. The middle class

is often depicted in terms of income. Much of the economic literature over the past several decades show the share of households

considered middle income is shrinking. An oft-cited 2015 study from the Pew Research Center defines middle-class households as those

with income between two-thirds to double the median household income.

5

A three-person household, for instance, would need an

income between $42,000 and $126,000 in 2014 to be considered middle class.

Discussion of the overall income spectrum, while stark, obscures just how unequal wealth and middle-class economic security is

distributed along racial lines. It is for this reason that we should be looking beyond the limited idea of income as the primary indicator of

middle-class status and instead recognize that wealth is and has always been the foundation of middle-class financial security.

Emphasizing this point, researchers from The New School, Duke Center for Social Equity and Insight Center for Community Economic

Development showed how income does not correspond with wealth, particularly when looking through the lens of racial inequality.

According to their study, Umbrellas Don’t Make it Rain: Why Studying and Working Hard Isn’t Enough for Black Americans, a typical

White family in 2011 in the lowest income quintile (i.e., those earning below $19,000) still owned $15,000 in wealth. By comparison,

African Americans making less than $19,000 annually owned just $100 in wealth. Overall, the researchers found that this pattern holds

true across the income spectrum.

Looking at the middle class through the lens of wealth, rather than income, Umbrellas Don’t Make it Rain found Black families with

incomes considered middle class—$42,000 per year—owned just $13,800 in total household wealth (including durable goods) in 2011.

That is not nearly enough to build long-term financial security by saving for retirement, to weather an unexpected medical procedure or

to put a child through college. In other words, as depicted below, a middle-class income does not guarantee a Black family middle-class

economic security.

Unfortunately, Black and Latino families have been subject to stagnant economic trends for decades and there is little evidence that this

will change. With their rising share of the population, these groups have a larger impact on the American middle class than they once

did, an impact that will only continue to grow. In fact, we already see the impact of declining wealth for Black and Latino households on

the nation’s collective economic well-being. During the past 30 years, African American and Latino median wealth has gone down while

White wealth has slowly increased. Overall, however, the median wealth of Americans has decreased from $78,000 in 1983 to $64,000

in 2013.

In other words, if the racial wealth divide continues to accelerate, the economic conditions of Black and Latino households

will have an increasingly adverse impact on the economy writ large because the majority of U.S. households will no longer

have enough wealth to stake their claim in the American middle class or higher.

To claim that the future existence of the middle-class hinges on whether we reverse the trends of growing racial economic inequality is

by no means an exaggeration. Indeed, the rise of a once-strong American middle class didn’t happen on its own. Rather, it required a

healthy, vibrant economy, including significant investments in Americans’ ability to build lasting financial security, such as through

homeownership, higher education and transportation, all of which enable families to build wealth. However, these policy investments

haven’t had a lasting positive effect on the middle class because most often, they were intentionally directed at White communities and

away from communities of color. Although the intentional exclusion of communities of color from opportunities to build wealth is a

morally repugnant feature of American history, it remained economically viable at a time when the vast majority of our populace was

White. As we look ahead to a time when people of color will comprise the majority of the population, however, we are committing

economic suicide if we continue believing that we can exclude the majority of the country from opportunities to invest in the future.

In other words, we have reached a breaking point. We need to act now to close the racial wealth divide, as doing so will ensure that the

historical injustices of the past do not continue to wreak havoc on household balance sheets or propel the American middle class into

extinction. Achieving this goal will require intentional, targeted policy solutions that address the economic needs of low-wealth

communities of color. In the remainder of this report, we argue that the only way to craft these solutions effectively is by moving

beyond the limited idea of income as the primary indicator of middle-class status to recognize that wealth is the linchpin of middle-class

economic security.

The Racial Wealth Divide & Middle-Class

Security

Just as overall wealth inequality has skyrocketed over the past 30 years,

6

so too has racial wealth inequality. In this timeframe, the

median wealth of Black and Latino households has taken dramatically different turns than the median wealth of White households,

leaving communities of color struggling in more pronounced ways while they watch their White neighbors thrive.

Since 1983, the respective wealth of Black and Latino families has plunged from $6,800 and $4,000 in 1983 to $1,700 and $2,000 in

2013. These figures exclude durable goods like automobiles and electronics, as these items depreciate quickly in value and do not hold

the same liquidity, stability or appreciation of other financial assets like a savings account, a treasury bond or a home. By comparison,

since 1983 the median wealth of White households has risen by nearly $15,000, reaching $116,800 in 2013. Put differently, in just over a

generation, median Black and Latino households saw their already-low net worth decrease by 75% and 50%, respectively, while median

White households saw their net worth increase by 14%. The result is a wealth divide between Black and Latino households and White

households that now stands at over $115,000, a nearly 20% increase.

Whereas these data reveal general trends in the years since 1983, we also see evidence that the Great Recession disproportionately

impacted households of color. Even with the wealth loss experienced by White households during the Recession, median wealth never

dipped below 1983 levels.

7

For households of color, on the other hand, the Great Recession wiped away the gains made over the past

three decades in their entirety. Put another way, although Black and Latino households started out well behind their White counterparts

in 1983, the Great Recession essentially set them back to where they started. At the same time, White households experienced only

minor setbacks, from which they have largely been able to recover.

Although these disparities are driven by several factors, disparities in homeownership rates account for much of the racial wealth

divide. For generations, White families have enjoyed access to wealth that has eluded their Black counterparts, making it far easier to

come up with downpayments and help their heirs claim their stake in the economy. Between 1994 and 2017, White homeownership

rates rose to 76%, compared to 49% for African Americans.

Since 2006, the homeownership rate has declined steadily for everyone—from 69% to 63% in the first quarter of 2017—but these losses

have been more pronounced for households of color. The homeownership rate among Black households fell from 48% in 2005 to below

42% in late 2016, while the Latino homeownership rate declined from 50% to 46% in the same time period. Meanwhile, the

homeownership rates for White households dropped from 76% to 72%.

8

Of course, while we believe that median wealth is a better indicator of the impact of racial economic inequality, we cannot ignore the

role income plays in nourishing the divide. At the median, White households make significantly more per year ($58,847) than Black

($35,600) and Latino ($42,396) households.

9

With less wealth and less income, there are few signs that Black and Latino households will

ever be able to “catch up” to their White counterparts.

For nearly a century, the United States has prided itself on its perceived broad and burgeoning middle class. Baked into the nation’s

mythology is the ideal of the comfortable, middle-class family that can afford the essentials of a happy, healthy life. That means a

house, a car and a few extras such as a family vacation. Middle-class families are also supposed to be able to afford health insurance and

child care, foot the bill for their kids’ college educations and save for a comfortable retirement. In public opinion polls, more than half of

Americans consistently refer to themselves as middle class.

10

Many who cannot afford half the items listed above include themselves in

that definition. Also included are most of the nation’s millionaires, who consider themselves middle or upper-middle class despite their

obviously outsized income

11

and their small representation (3.3%) among the country’s overall population.

12

When looking at where Black and Latino communities fall within the middle class through the lens of wealth, the typical Black or Latino

family not only lacks enough wealth to be considered middle class, but they hardly have any wealth at all. To better understand the

disparities between income and wealth and just how removed communities of color are from the middle class, we look at wealth as the

key indicator of what it means to be middle class.

For the purposes of this study, “middle-class wealth” (or “middle-wealth”) is defined using median White household wealth since it

encompasses the full potential of the nation’s wealth-building policies, which have historically excluded households of color. More

specifically, we use median White wealth in 1983 ($102,200 in 2013 dollars) as the basis for developing an index that would encompass

“middle-class wealth” because it establishes a baseline prior to when increases in wealth were concentrated in a small number of

households. Using this approach and applying Pew Research Center’s broad definition of the middle class,

13

this study defines “middle-

class wealth” as ranging from $68,000 to $204,000 (see Methodology for more details).

Using this index to examine recent Census Bureau data, we more clearly see the stark racial gap in middle-class wealth between White

households and households of color. That data reveal that White households in the middle-income quintile (those earning $37,201-

61,328 annually) own nearly eight times as much wealth ($86,100) as Black households in the middle-income quintile ($11,000) and ten

times as much as Latino households in the middle-income quintile ($8,600). This stark disparity isn’t isolated within the middle-income

quintile—White families across the income spectrum own significantly more wealth than their Black and Latino peers.

In essence, Black and Latino families in the middle-income quintile would need to earn 2-3 times as much as their White counterparts to

exceed the minimum wealth threshold of $68,000 needed to qualify as middle class. Meanwhile, White households in the top three

income-quintiles already own wealth in excess of this threshold.

While the estimates derived in this report are generally consistent with and representative of the population at large, the percentage of

the population with wealth below or above the “middle-class wealth” range previously defined varies widely. By our estimates, roughly

70% of Black and Latino households fall below the $68,000 threshold needed for middle-class status, while the same can be said of only

about 40% of White households. On the other end of the spectrum, about 13% of Black and Latino households could be considered to

have “upper-class wealth” (meaning they own at least $204,000 in wealth), compared to 40% of White households who meet this

threshold.

If we consider educational attainment— often considered as the “great equalizer” between the rich and the poor and between families

of different racial and ethnic backgrounds—White families whose head of household holds a high school diploma have nearly enough

wealth ($64,200) to be considered middle class. A typical Black or Latino family whose head of household has a college degree however,

owns just $37,600 and $32,600, respectively, in wealth. In fact, only Black and Latino households at the median with an advanced

degree have enough wealth to fit into our middle-class definition. By contrast, all White households except those who fail to attain a

high school diploma could be considered middle class.

Running Out of Time: The Racial Wealth Divide

in the Trump Era

The racial wealth divide is not a new phenomenon, nor can a single presidential administration or other policymaking body expect to

ameliorate the racial wealth divide overnight. However, since the inauguration of President Trump in early 2017, two phenomena give

cause for concern that the trends of the past 30 years might become even more pronounced in the near future. First, less attention has

been paid to the growing racial wealth divide compared to previous administrations. Second and more alarmingly, there have been a

bevy of policies proposed or championed by President Trump—from health care to immigration to housing and financial services

reform—that would inevitably and exponentially exacerbate racial wealth inequality.

In this section, we look ahead to 2020 and 2024 to see what the racial wealth divide will look like if no proactive measures are taken to

address the problem. These projections do not, of course, account for the disproportionate impact of the aforementioned policies on

communities of color if President Trump is successful in bringing those initiatives to fruition.

By 2020, if current trends continue as they have been, Black and Latino households at the median are on track to see their wealth

decline by 17% and 12% from where they respectively stood in 2013. By then, median White households would see their wealth rise by

an additional three percent over today’s levels. In other words, at a time when it’s projected that children of color will make up most of

children in the country,

14

median White households are on track to own 86 and 68 times more wealth, respectively, than Black and

Latino households.

Current trends suggest that by 2024, median Black household wealth will have declined by a total of about 30% from where it stands

today. In that same timeframe, the median Latino family can expect to see their net worth decline by a total of 20% over today’s levels.

By then, median White household wealth will have increased by about five percent over today’s levels.

Overall, this dizzying decline in Black and Latino household wealth would mean that seven years from now, median Black and Latino

households would own 60-80% less wealth than they did in 1983. Put differently, by the end of the next presidential term (in January

2025), median White households would own 99 and 75 times more wealth, respectively, than Black and Latino households. By then, the

racial wealth divide will have increased by more than $6,000 from where it stands today.

These projections assume that the racial wealth divide would be left unattended and that it would not be exacerbated between now

and then; the numbers above reflect current policy. However, the proposals put forth by the current administration and by Congress

could catalyze an even more significant divide than what is reflected in the table above. For example, as we highlight in more detail later

in this report, the tax code already plays an outsized role in fueling economic inequality, as the wealth-building tax benefits that flow

from it overwhelmingly go to wealthy—mostly white—households while providing little wealth-building support to the people who

need it most.

According to a recent study by the Tax Policy Center, President Trump’s current tax plan would give families earning $25,000 or less

annually a tax cut of only $40 tax cut, while those earning more than $3.4 million annually would receive a $940,000 tax break.

15

As a

result, the passage of this tax plan into law would only serve to double-down on the upside-down nature of the tax code, boosting

wealth inequality to even more outrageous heights.

Looking past 2024 to 2043, when Americans of color are projected to outnumber White Americans, the declining wealth for Black and

Latino households will account for a projected loss of an additional $11,000 in overall household wealth. At this rate, the country’s

median household wealth (excluding durable goods and adjusted for inflation) will be just $52,300 in 2043—32% less than what it was

in 1983.

To be clear, there’s no need to wait until then to know the impact of the racial wealth divide on the middle class. Overall median wealth

of households today ($63,800) already falls short of the $68,000 threshold required to be considered middle class.

Looking beyond 2043, the situation for households of color looks even worse. While these families are expected to sustain significant

losses in wealth in the next few decades, they are actually projected to hit zero wealth just ten years after people of color become the

majority in the United States. If unattended, trends at the median suggest Black household wealth will hit zero by 2053. In that same

period, median White household wealth is expected to climb to $137,000. The situation isn’t much brighter for Latino households,

whose median wealth is expected to reach zero by 2073, just two decades after Black wealth is projected to hit zero. By this time, the

median wealth of White households is projected to have reached $147,000.

For Black and Latino communities that already find themselves consistently on the edge of financial insecurity, this steep and steady

slide to zero median wealth will only serve to compound the already-sizeable challenges facing these communities. Wealth is an inter-

generational asset—its benefits passed down from one generation to the next— and the consequences of these losses will reverberate

deeply in the lives of the children and grandchildren of today’s people of color.

Of course, Black and Latino households having zero wealth isn’t just an issue for future generations to be dealt with later. Already today,

we have significant portions of these households owning zero wealth. As of 2013, 30% and 24% of Black and Latino households,

respectively, had zero or negative net worth, amounting to 7.6 million households.

Often, discussions about racial equity and economic inequality focus exclusively on Black and Latino communities. Even in this report,

we have focused thus far on Black and Latino families and not other racial groups. In part, the focus on Black and Latino groups can be

attributed to the fact that the economic insecurities facing these particular communities is much easier to see. However, the lack of

compelling data about other racial and ethnic minorities should not be treated as evidence that they do not face mounting economic

inequality. To the contrary, there are often significant gaps between their wealth and the wealth of their White counterparts.

When it comes to Asian American communities, their struggles with economic inequality are often overlooked due to prevailing

stereotypes and the oversimplification of economic data, which consolidates 21 million culturally diverse people

16

from 48 countries,

each with different contexts of immigration and wealth, into a single group. This consolidation further perpetuates the “model

minority” myth of Asian households as being unequivocally better off than other communities of color.

Beyond serving as a wedge in conversations about race and economic mobility, aggregating economic data about Asian American

communities obscures clear social and economic differences within the Asian communities in the US, particularly when it comes to

wealth. To this point, recent research by the Center for American Progress has found that overall affluence and economic well-being

associated with Asian Americans is not shared across the entire community, and that in fact, many face serious wealth inequality

challenges.

17

When economic data for Asian Americans are disaggregated, wealth inequality is actually more significant among Asian

American households than compared to White households. For example, between 2010–2013, the top 10% of Asian Americans owned

$1.4 million in wealth, while the bottom 20% of Asian Americans owned about $9,300. By comparison, the top 10% of White households

owned $1.2 million, while the bottom 20% of White households owned a little more than $10,000.

18

Overall, the richest Asian

Americans held 168 times more wealth than the poorest Asian Americans, while the richest White households owned 121 times more

wealth than the poorest White households.

19

Although median Asian American households are generally more affluent than the median White households, these disaggregated data

reveal both a greater concentration of Asian American households at the bottom, and a highly skewed average due to wealth

distributions at the top. For example, in addition to bringing further attention to the level of wealth inequality experienced within the

Asian American community itself, researchers at the Center for American Progress found that the poorest Asian Americans own far less

wealth than their White counterparts. Today, among households in the bottom half of the income distribution, White households

owned more than twice the wealth ($42,238) held by their Asian American peers ($18,270). All of these data point to a significant

wealth divide between White and Asian American households over the past 25 years that is often overlooked.

20

Not unlike Asian Americans, our collective focus on the social and economic issues facing Native Americans is also influenced in part by

availability of and methods for collecting economic data that shed light on these communities. However, when it comes to Native

American data, the issue for these communities is less often about how they are seen and more often about if they are seen. Whereas

aggregated economic data about Asian households are often skewed, Native American economic data are often outdated, difficult to

collect and/or insufficient to interpret reliably. In turn, the unique economic experiences of Native Americans are often overlooked,

even though these experiences tend to be comparable or worse than those of Black and Latino households.

While we do have access to a range of current data on income, including median household income ($38,530, 30% less than the than

the national median)

21

and poverty rates (26.6%, roughly twice the national rate),

22

when it comes to Native American net worth, scant

data are available to illustrate to the current state of wealth within these communities. In fact, when it comes to wealth, the most

recent data available for Native American communities are seventeen years old. In 2000, the last time Native American wealth was

systematically measured, the median net worth of Native households stood at just $5,700.

23

Ultimately, the problematic nature of data on Asian American wealth and the dearth of data on Native American wealth complicate our

discussion of the racial wealth divide in three important ways. First, and most obviously, these challenges mean we lack the data

needed to fully understand—and therefore design solutions to—the unique problems facing these communities. Second, and closely

related, insufficient, unreliable and aggregated data prevent us from seeing the full scope of the racial wealth divide and its inevitable

impact on the middle class if left untreated. Third and finally, in the absence of these data, we make generalizations about groups of

people that not only perpetuate problematic narratives, such as that of the “model minority,” but also fail to see the urgency with which

some of our neighbors are suffering the effects of decades or centuries of economic exclusion. Hence, any solution to growing racial

wealth inequality will demand that we also refine our abilities to collect and interpret data that shed light on the lived economic

realities of these communities.

Across most economic indicators, White families today fare significantly better than families of color. As scholars like Thomas Shapiro,

William “Sandy” Darity, Darrick Hamilton, Mariko Chang and others have argued, this disparity is rooted in our social systems and

structures, not in individual behaviors. And, although emphasis has recently been placed on the role that public policies have played in

the economic pain suffered by White working-class communities, there is no shortage of evidence that public policies and practices

throughout our history have worked to benefit White families at the expense of communities of color.

Today, the legacies of these policies and practices have metastasized across a whole range of economic inequities, leaving communities

of color far short of their economic needs and unable to achieve financial security, let alone build wealth.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Ultimately, how communities of color arrived at many of these and other harsh economic realities can be directly traced to institutional

and pervasive racial discrimination across a series of systems, policies and practices from our very beginnings throughout present day,

which together have systematically worked in favor of the wealth-building potential of White households at the exclusion and expense

of the wealth-building potential of communities of color.

While the racial wealth divide can be largely attributed to the effects of discriminatory and exclusionary policies and practices put in

place in the years after the Great Depression and World War II, the foundation for this divide had been forged long before we reached

either of these points in our history. From the earliest days of our country’s infancy through the late 19

th

century, a range of policies and

practices laid the foundation for this divide include.

African Chattel Slavery and Wage Theft: Throughout the 246 years when slavery was an institution in the United States, the forced and

free labor extracted from enslaved men, women and children allowed White slave owners to accumulate massive amounts of wealth.

To crystalize what this free labor meant to the wealth-building potential of White slaver owners, and what it cost those who actually

earned it, consider that by 1860, the lower Mississippi Valley—land about the of size Maine—had more millionaires per capita than

anywhere else in United States.

39

Racially Exclusive Land Redistribution: Through the Homestead Act, approximately 270 million acres, or about 10% of all land in the

United States, was given to over 1.6 million homesteaders. Today, research finds 46 million adults, or about 20% of the U.S.

population, can potentially trace their family’s history of building wealth to this one public policy.

41

Yet, despite the impact of the

Homestead Act and the fact that it allowed for any adult—including Black adults—to claim a 160-acre parcel of land, it still

disproportionately benefited White households. For example, African Americans, who ran into a series of legal obstacles put in place by

White southerners to block former slaves from becoming property owners, couldn’t claim legal ownership of the land offered to them

by the Homestead Act.

42

Of course, we would be remiss if we did not acknowledge that the Homestead Act was possible because of land

stolen by the U.S. government from indigenous people, marking another dark spot in the long history of colonization, wars, genocide,

deceptive practices and forced expulsions that prevent Native peoples from thriving still today.

Denying Access to the Asset of Citizenship: The Chinese Exclusion Act was enacted in 1882, placing a 10-year ban on Chinese workers

immigrating to the US and naturalizing in order to appease economic and cultural concerns raised by White Americans at the time. In

1892, the Geary Act extended the original ban for another 10-year period before it was made permanent in 1902. As a result, these

communities could not take advantage of land-owning opportunities or build long-term financial security because citizenship was often

a requirement for owning property under the Homestead Act and state laws that mirrored it. The experience of Chinese immigrants is

far from unique for communities of color, for whom denying the benefits of citizenship has more often been the rule than the

exception. In fact, racially discriminatory immigration policy was the norm from 1790 until 1965, when it became illegal to deny people

access to citizenship on the basis of their race. Still today, we see how immigration laws use race as a justification for discrimination,

even if it is illegal to grant citizenship status on the basis of race.

Although the foundation of the racial wealth divide was laid during America’s formative years, it wasn’t until first part of the 20

th

century when the racial wealth divide we have come to know today was accelerated. Three practices in particular contributed to this

acceleration.

Denial of Social Security to Farmworkers and Domestic Workers: In 1935, the groundwork for the nation’s social safety net

infrastructure was laid with the passage of Social Security Act. Yet, despite the significance and importance of the legislation, the Social

Security Act of 1935 excluded a third of all American workers, including farmworkers and domestic workers—who were predominately

people of color—from coverage under the legislation.

43

For African Americans, the cost of exclusion from the Social Security Act of 1935

resulted in a loss of benefits totaling $143.20 billion in 2016 dollars.

44

To be sure, White workers were also denied the benefits of Social

Security—to the tune of $461 billion, in fact. However, although White farmworkers and domestic workers were excluded, African

Americans and other minority workers bore the brunt of the impact as they comprised a much larger share of those excluded—about

two-thirds—compared to White workers.

45

Federally Sanctioned Housing Discrimination: Between 1934 and 1968, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), along with other

public- and private-sector actors like the federal Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), intentionally shut out households of color

from the opportunity to purchase a home through the practice of redlining. Despite FHA’s goal of making homeownership accessible to

more American households, the underwriting practices it implemented during its first 35 years resulted in homebuyers of color

receiving just two percent of the government-backed mortgages issued over that period of time.

46

The practice of being denied access

to traditional credit pushed many would-be homebuyers of color into wealth-stripping “land contracts,” a predatory and costly

arrangement in which buyers paid an exorbitant price to purchase a home and in which a missed payment would lead to eviction from

the home and the loss of all equity. In cities like Chicago, where redlining was rampant, the practice of “land contracts” led African

American families to pay an average of $20,000 more for their homes than the prices paid by White families, ultimately stripping more

than $500 million in wealth (about $3 billion in 2017 dollars) from families of color over a 30-year period.

47

Ultimately, this practice not

only set the stage for homeownership to become the largest driver of the racial wealth divide today, it also shaped—figuratively and

literally—the communities in which many people of color live today.

48

Denial of Economic Opportunities for Servicemembers of Color: By and large, the G.I. Bill of 1944 is credited with providing millions of

returning World War II veterans with the opportunity to access wealth-building opportunities, including low-cost home mortgages, low-

interest business loans and tuition assistance. Although the bill did not include discriminatory language or directives, it delegated

administrative authority to the states with minimal federal oversight. The result was pervasive racial discrimination in which

Servicemembers of color were more likely to be denied access to a range of benefits that greatly expanded the American middle class

that arose during the second half of the century.

49

As with redlining, discriminatory lending practices among Servicemembers of color

were prevalent, leaving veterans to face racially biased administrator that were unwilling to extend G.I. benefits, as well as banks that

were unwilling to extend credit to people of color.

50

For example, three years into the administration of the law, a survey of 13

Mississippi cities found that African American Servicemembers received just two of 3,229 loans made by the Department of Veterans

Affairs to support homeownership, business and farming.

Even though many policies and practices that have impacted the economic potential of communities of color have been outlawed or

corrected, today there remains a whole host of policies and systems that either limit the ability of households of color from building

wealth or strip away what little wealth they might have. The policies discussed below are just a few of the most enunciated examples.

The Punishment of Our Most Vulnerable for Trying to Get Ahead: Despite the fact that social safety net programs are designed with

the explicit purpose of helping families climb out of poverty, many public benefits programs—in which households of color are more

likely to participate than their White counterparts

51

— punish families for even modest savings that might help them get ahead. These

savings penalties are often called “asset limits,” and they limit eligibility for many means-tested government assistance programs to

those with very little or no savings.

52

In some states, as little as $1,000 in a savings account earmarked for a child’s college education

results in families losing access to critical public assistance programs like SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly

food stamps) or TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families). Even owning a car—an asset that many workers need to get to their

jobs, remain employed and move off of public assistance—that is valued above a certain threshold (currently $4,650 for the

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) can disqualify a family from these critical safety net programs.

53

Although many states have

taken advantage of the flexibility they have to lift or remove these penalties entirely, many other states have failed to leverage this

flexibility and there continue to be efforts at the federal level to take away that flexibility entirely.

The Perpetuation of Financial Insecurity by the Criminal Justice System: Today, 70-100 million Americans have a criminal record.

54

Given that communities of color make up a disproportionate amount of the incarcerated population (African Americans and Latinos

alone account for more than half of the prisoners in 12 states)

55

and that these communities are more likely to interact with and be

affected by the sprawling criminal justice system,

56

its impact on the racial wealth divide cannot be ignored. For example, the debts

generated by a system of fines and fees can often leave individuals who interact with this system in an unsettling economic situation,

even after they have repaid their debts to society or have been cleared of any wrongdoing. In Washington—a state with lower

incarceration rates than 39 other states

57

—criminal debts stripped 36-60% of the income of formerly incarcerated men.

58

At the

national level, the burden of the more $50 million in criminal debts are held by just 10 million people, or about three percent of the

population.

59

Unfortunately, criminal debts are often compounded further by a number of other challenges, including difficulties in

securing employment. To this point, the American Bar Association has found that of the more than 46,000 collateral consequences or

civil penalties of federal and state criminal convictions, 60-70% are employment-related.

60

An Upside-Down U.S. Tax Code That Overwhelmingly Favors Wealth-Building for Wealthy—Mostly White—Households Over

Everyone Else: Our tax code is—by leaps and bounds—the single largest tool the federal government uses to provide families with the

support they need to boost economic outcomes and build lifelong wealth. To achieve these goals, the federal government spent $677

billion through the tax code in 2016 to help families purchase a home, go to college, and save and invest for the future. Together, this

amount surpasses the budgets of all federal agencies combined, save for the Department of Defense. While the government’s goal of

helping families build wealth is laudable, the problem is how the tax code disburses the bulk of this spending—the support ends up

going almost exclusively to the already wealthy, providing very little or no support to low- and moderate-income families, particularly

those of color.

Despite the IRS not collecting data on tax filers’ race, in 2014, PolicyLink published a study that provided for the first time an

approximation of which racial groups benefit most from tax expenditures. In it, researchers found that White households represented

the majority of income earners in each income quintile, including in the top three quintiles. It is in these three income quintiles where a

lion’s share of available tax breaks were claimed, including exclusions, itemized deductions and investment credits. An updated

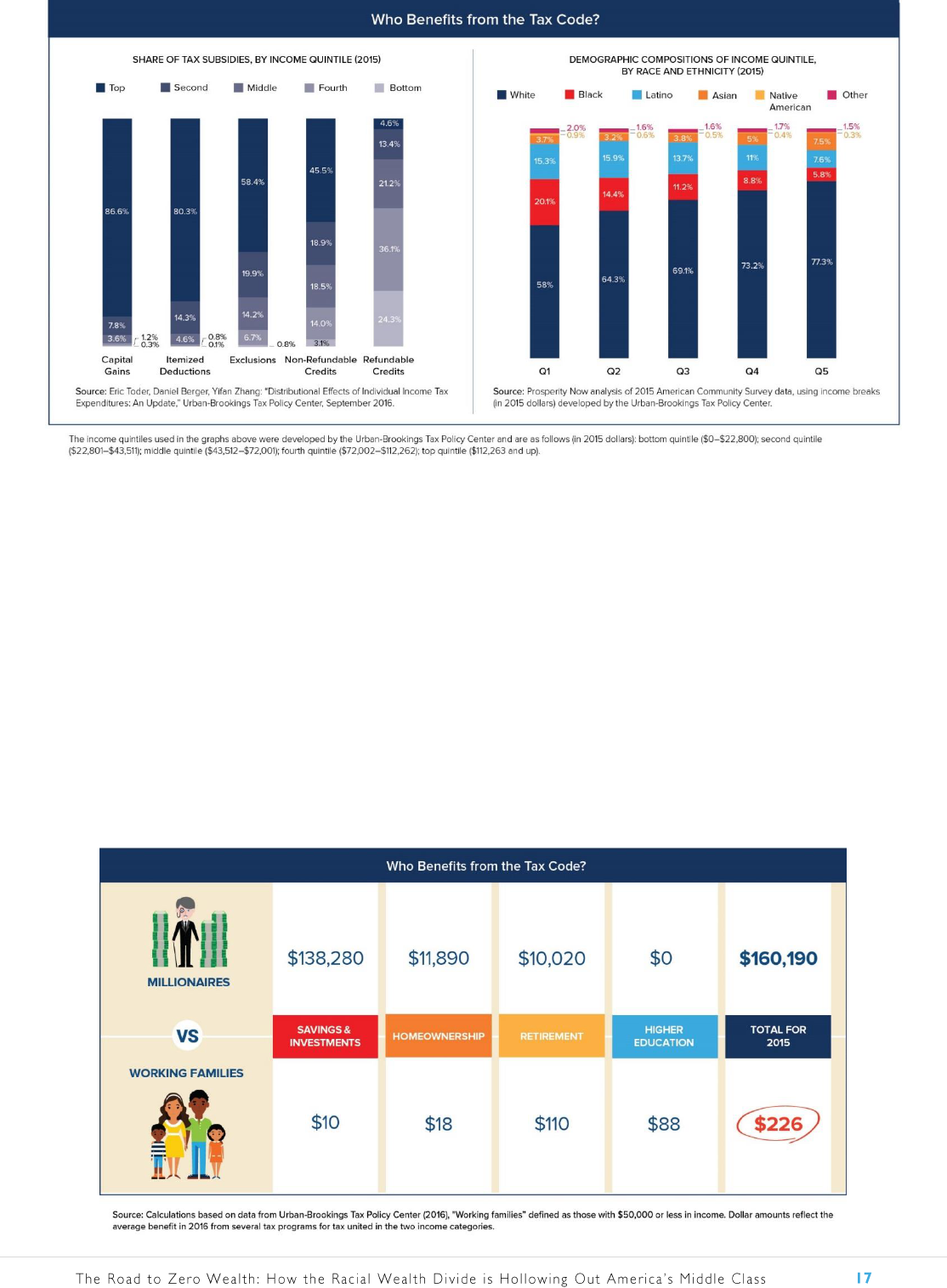

representation of those findings is depicted in the graphs that follow.

For a specific example of how the tax code is making the problem of wealth inequality worse look no further than the tax provisions that

encourage homeownership, which makes up the largest share of a household’s wealth. In 2015, the federal government spent $51

billion on public housing assistance programs, which was a little less than half of what was spent through the tax code to support

homeownership during the same year through the Mortgage Interest Deduction and the Property Tax Deduction ($90 billion).

61

Although both programs support families in their efforts to secure a roof over their heads, families earning $100,000 or more took 90%

of the $90 billion available through tax-related housing assistance, while those earning $50,000 received only about one percent of

these benefits.

62

In other words, despite the shared goal of boosting housing opportunities for Americans, wealth-building tax programs

are designed to help the wealthy become even wealthier.

At the heart of the disparities perpetuated by the tax code are several flaws, including the fact that most of our most valuable wealth-

building tax benefits—such as the Mortgage Interest Deduction—are only available to tax filers who itemize their deductions. According

to recent research by the Urban Institute, high-income earners were overwhelmingly more likely to itemize their deductions than lower-

income earners. In fact, as of 2014 (the most recent year data are available from the IRS), more than 80% of tax filers earning $100,000-

$499,000 itemized their deductions, while 92% earning $500,000 or more did the same. By comparison, only 22% of those earning

$30,000-$49,000 and just seven percent of those earning less than $30,000 itemized their deductions. Adding to this structural problem

is that taxes are complicated. When we understand how this system works, it becomes clear that the vast amount of spending done

through it goes to help wealthy families build more wealth, instead of helping those are struggling to get ahead.

Policy Interventions to Address a Growing

Crisis

The growing racial wealth divide documented in this report is not a natural phenomenon, but rather the result of contemporary and

historical public policies that were intentionally or thoughtlessly designed to help White households get ahead at the expense and

exclusion of households of color. In other words, this crisis is not the result of individual behavior, but rather of structural and systemic

forces. Although public policy has been a significant contributor to the divide, the good news is that public policy can also help to close

the divide.

However, if we are to be successful in designing policies that ultimately close this growing gap, then we must operate within a different

framework than the one that led us to this point. In this section, we discuss what this framework should look like, acknowledging both

that no single policy will suffice, and that our policy prescriptions must emphasize benefits based on existing wealth needs and barriers,

including taking proactive steps that disproportionately benefit low-wealth communities of color.

63

UNDERSTAND THE PROBLEMS FACING LOW-WEALTH HOUSEHOLDS

Gathering enough information to make informed decisions about public policy is critical to ensuring to solving the

problems outlined in this report.

Racial Wealth Divide Government Audit: In our 2016 report, The Ever-Growing Gap, we described in detail a plan for an audit of

existing public policies to determine their impact on the racial wealth divide. This audit, we argue, should be government-wide and

evidence-based, with a special advisor or ombudsperson overseeing the project. The Institute on Assets and Social Policy at Brandeis

University has created an empirical tool for conducting a racial wealth audit.

64

It’s critically important that the findings of such an audit

are made public and paired with actionable options for administrative reforms. Policies found to be intensifying the racial wealth divide

should be critically re-evaluated, while policies that reduce the divide should be expanded. Creating a racial wealth audit is well within

the authority of the Executive branch and should be implemented in concert with a legislative agenda that changes policies found by the

audit to be unduly hurting communities of color.

Improve Data Collection on Economically Disenfranchised People: Access to high-quality data is critical to understanding the economic

trends outlined in this study. However, a major limitation of the study results from the dearth of nationally representative data on a

wider range of ethnic and racial groups. For instance, while much information is available on White, Black and Latino families,

comparably little information is available about Native American household finances. More data, specifically those which disaggregate

Asian American communities and those which shed light on Native Americans’ economic lives, would enable a deeper discussion of the

role of race in economic inequality.

INVEST IN LOW-WEALTH HOUSEHOLDS

Invest in low-wealth households by fixing unfair, upside-down tax programs, reducing wealth concentration at the

top and generating significant funding to be reinvested in the wealth-building potential of low-wealth individuals

and families.

Turn Upside-Down Tax Expenditures Right-Side Up: When most people think about government spending, they think about what the

government buys with its money, not about the discounts it gives. In effect, these discounts—what are commonly referred to as tax

expenditures—function in the same way that public spending programs do, albeit with much less scrutiny. The impact of tax

expenditures is quite large and could make up the basis for shifting public investment in asset generation for low-wealth families. As

described previously in this report, the existing federal tax expenditures add up to $677 billion spread across efforts to boost savings,

homeownership, retirement and higher education. Currently, we spend:

• $251 billion to boost savings and investments by actively increasing accessible savings through investments and inheritances.

• $220 billion to support homeownership through tax programs that primarily enable households to take on more mortgage

debt and buy bigger homes.

• $178 billion to support retirement through tax-preferred treatment of retirement plans, such as defined benefit plans, 401(k)s

and IRAs.

• $28 billion to support higher education through after-purchase subsidies and support for college savings

Due to the massive amount of money spent through these wealth-building tax programs and their far reaches, shifting these tax

expenditures toward wealth-building programs for low-wealth people would have a monumental impact in reducing the racial wealth

divide and solving economic inequality more broadly.

Expand Existing Progressive Taxes: In addition to broad reforms to our wealth-building tax programs, other solutions for generating

significant revenue while reducing the democracy-distorting impact of concentrated wealth include:

• Robust Estate and Inheritance Taxation. Over the last decade, the federal estate tax has been weakened through higher

exemptions and the increased use of loopholes, such as the Granter Retained Annuity Trust. Closing these loopholes and instituting

a graduated rate structure would generate additional revenue and reduce the distorting impact of concentrated wealth. Reform

proposals under consideration in Congress, like the Responsible Estate Tax Act, would generate between $161-200 billion in

estimated additional revenue over the next 10 years.

65

• Net Worth Tax on Fortunes. Lawmakers should explore the creation of an annual net worth tax on wealth over $50 million or a

similarly high threshold, at a low rate of 1-2%. Annual net worth taxes have existed in other OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-

operation and Development) countries and are part of a constellation of policies to reduce concentrated wealth and generate

revenue for opportunity investments.

66

• State-Level Estate and Wealth Taxation: In 2001, Congress phased out the linkage between state and federal estate taxes, leading

to the expiration of estate taxes in over 30 states. Eighteen states and the District of Columbia proactively retained their estate

taxes, although they’ve been under attack ever since. In Washington, state estate tax revenue capitalizes the Education Legacy

Trust Fund, which funds K-12 and higher education in the state. If states without estate taxes reinstituted them, they could

generate $3-6 billion per year that could be invested in expanding opportunity.

67

Fix the Hidden Wealth Problem: Efforts to reduce the racial wealth divide run headlong into the growing practices of hiding wealth

from taxation and accountability. New research suggests that households in the top 0.01% (i.e., those with wealth in excess of $40

million) evade 25-30% of personal income and wealth taxes.

68

By comparison, the general population has an evasion rate of just three

percent.

The use of “off shore” tax havens –or secrecy jurisdictions –is becoming more widespread in the last few decades, both for transnational

corporations and wealthy individuals. Economist Gabriel Zucman estimates that about 8 percent of the world’s individual financial

wealth –almost $8 trillion –is hidden in these off-shore centers. Wealthy U.S. citizens have an estimated $1.2 trillion stashed off-shore,

avoiding $200 billion a year in lost tax revenue.

69

This estimate is probably low. Jim Henry, a former economist at McKinsey, calls the

offshore financial world the “economic equivalent of an astrophysical black hole,” holding at an estimated $21 trillion of the world’s

financial wealth, more than the gross domestic product of the United States.

70

Dealing with this hidden wealth problem will require legislative action, international diplomacy, and sanctions and penalties aimed at

banks, tax haven jurisdictions and the wealth defense industry professions that facilitate the process.

The US has enormous responsibility and leverage in fixing this broken system, given our oversized role in the global economy. In doing

so, the US should require transparency reforms and shared reporting as part of international trade agreements. Moreover, foreign

banks and corporations should be held to higher standards of reporting in order to have access to U.S. markets. Several promising ideas

for tackling this challenging problem include:

• Transparency Reforms: As part of global trade negotiations, countries should establish treaties requiring uniform disclosure

and transparency, both of banks and capital flows. Private bank accounts should be required to disclose ownership of different

accounts. And, states like Delaware and Wyoming should have higher transparency and disclosure requirements.

• Reforms to the Off-Shore Corporate Tax Haven System: Some of the policy actions that would greatly reduce corporate tax

haven abuses include:

o Global Registries of Beneficial Ownership. International treaties should require banks and corporations to register

their beneficial owners, ending one of the hallmarks of secrecy in the offshoring system.

o End Deferral of Foreign Source Income. The Corporate Tax Fairness Act would require U.S. companies to pay taxes on

all of their income by ending the deferral of foreign source income.

o Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act. Introduced by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) and Representative Lloyd Doggett (D-

TX), the “Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act” (H.R.1932/S. 851) is an omnibus bill that would close a number of loopholes and

empower the IRS to identify and close foreign tax shelters.

71

o Outlawing Certain Practices and Trusts. While respecting principles of privacy, certain practices deliberately designed

to mask ownership of wealth, bank accounts, corporations and transactions must be declared illegal—along with the

intent to design new loopholes and mechanisms that have yet to be discovered.

o Exposing and Penalizing the Enablers. One approach is to focus on holding the wealth defense practitioners directly

responsible for aggressive tax avoidance, including criminal charges for aiding and abetting services.

IMPROVE ACCESS TO LIFE-LONG WEALTH-BUILDING OPPORTUNITIES

Improving life-long wealth building opportunities so children have access to job training and college degrees is key

to reducing barriers to wealth creation.

Establish Children's Savings Accounts: Imagine if every child in the United States started off with a small nest egg for her future in the

form of a Children's Savings Account (CSA) opened automatically at birth. CSAs are rather simple in design: children receive an initial

deposit at birth that, along with contributions from families and the children themselves, accrues interest throughout their childhood

and becomes available to them as an adult. Uses for the funds can be limited to education, homeownership, starting a business or

retirement. The idea for CSAs has been around for a long time, although CSAs have never been implemented at the national level in the

United States.

72

That is a particular shame in light of a 2016 report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation showing that if Congress had

instituted a robust universal CSA program in 1979, the White-Latino wealth gap would be fully closed by now and the White-Black

wealth gap would have shrunk by 82%.

73

GENERATE MORE INCOME AT THE BOTTOM OF THE WAGE SPECTRUM

To address the growing economic divide between White and non-White households, opportunities for generating

more income need to be available to those at the bottom of the wage spectrum.

Strengthen the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): The EITC is not well understood for families who’ve never received it or for folks who

don’t spend their days contemplating tax policy. In large part, the credit’s complexity is often a major barrier for low- and moderate-

income households to claim it in the first place. As a result, about one out of every five eligible tax filers do not claim the credit.

74

Given the important role the EITC plays as the country’s largest and most effective anti-poverty program,

75

it is critical that we expand,

improve and simplify the credit. Today, the full benefit of the EITC currently only extends to parents, a policy that should change to

include low-wealth workers without dependents. Another smart refinement would be to allow and incentivize families to save a portion

of their EITC for a rainy day later in the year. Benjamin Harris and Lucie Parker of the Tax Policy Center found in a 2014 study that Black

families disproportionately live in ZIP codes with high rates of poverty and high rates of EITC claims. Thus, improving the EITC would

bring direct benefits to the families in these communities.

76

Significantly Raise the Minimum Wage: The minimum wage is too low to afford the basic cost of living in any major city in the country.

Despite the fact that workers are significantly more productive today, the federal minimum wage has not increased since 2009 when it

rose to $7.25 per hour ($2.13 an hour for tipped workers). Federal efforts to raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour backed by the

national “Fight for 15” campaign would significantly reduce the racial economic divide.

Studies conducted on cities that dramatically raised their minimum wage have shown significant economic benefits for the low-wage

workers, as well as for the communities as a whole. Michael Reich and his colleagues at the University of California at Berkeley looked at

the impact of raising the minimum wage in cities that had done so, including Chicago, San Francisco, Oakland and Seattle.

77

They found

that higher wages boosted worker pay, contrary to concerns that higher minimum wages would cause either a loss of jobs or a

slowdown in economic growth. Other research has shown that there are more benefits to raising the minimum wage, including

increasing worker productivity,

78

reducing poverty and reliance on public assistance programs,

79

and improved infant health and adult

mental health, including a significant reduction in depression.

80

Guarantee Employment: On their own, raising wages and tweaking the tax code cannot sufficiently enable low-income people to earn

their way out of poverty. Unemployment rates for Black workers are consistently higher than those of their White counterparts. A

federal job guarantee would address this problem. Championed by a number of economists including Darrick Hamilton and William

“Sandy” Darity, a federal jobs guarantee would function similarly to the Works Progress Administration of the 1930s.

81

A federal jobs

guarantee would also help address the growing infrastructure crisis in the United States to fix the nation’s crumbling roads and bridges.

ENCOURAGE AND ENABLE SAVINGS

Encouraging and enabling savings for low-wealth communities of color is a critically important role for public policy.

The key savings vehicle for most families is their retirement savings, which very few low-income people are able to

build.

Create a National Automatic-Enrollment Individual Retirement Account (Auto-IRA) Program: Employees of color are more likely to

lack access to and less likely to participate in work-based retirement plans.

82

Even more unfortunate is that even those who do save for

retirement don’t have enough saved to live out their golden years in dignity. Today, median Black and Latino families (age 32-61) have

just $22,000 saved in a retirement account, compared to $73,000 for the median White family.

To address the retirement gap facing communities of color, Congress should make it easier for any American to save for their retirement

by enacting a national Auto-IRA program in which workers have the ability to opt out if they choose. At minimum, research has shown

that a policy solution such as this would dramatically increase participation rates in retirement savings plans by 90%.

83

Some other ideas

for encouraging retirement savings for low-income people include expanding the Saver’s Credit—a tax credit aimed at encouraging

lower-income households to save for retirement—into a refundable credit, making it accessible to more low-wage families.

INCREASE OPPORTUNITIES TO OWN WEALTH-BUILDING ASSETS

Homeownership has been a pillar of the middle class for decades, yet incentives for buying a home or generating

other assets are skewed by a tax expenditure system that privileges the already wealthy.

Increase Access to Homeownership & Housing Opportunities: The Mortgage Interest Deduction is considered a “third rail” in

Washington policy discussions, meaning it can’t be touched. However, this particular program is worth singling out as its current design

exacerbates inequality by utilizing public dollars to benefit wealthy households at the expense of low-wealth households. Over $75

billion is spent annually on the deduction.

84

Congress should consider a meaningful cap on homeownership tax support and use the

savings from such a cap to help low-wealth families access homeownership and affordable housing—rather than helping the wealthy

afford their second or third homes. These funds could be redirected in several ways, including by:

• Reinstating the First-Time Homebuyer Tax Credit and making it permanent.

• Creating a refundable housing credit that would allow more taxpayers—both homeowners and renters—to enjoy the housing

benefits of the tax code.

• Create a matched-savings program for downpayments to help more would-be homeowners overcome financial barriers to

purchasing a home.

Reforms like these could be used to greatly reduce the racial homeownership disparity that exists today, which research has shown

could narrow the racial wealth divide by as much as 31%.

85

PROTECT HOUSEHOLD WEALTH AGAINST WEALTH-STRIPPING PRACTICES

Defending the gains made by low-wealth households from wealth stripping and other attempts to undermine their

asset-building efforts is critically important.

Maintain the Effectiveness & Independence of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB): Although there are a number of

different agencies that regulate all aspects of the financial industry, the CFPB is the only agency dedicated solely to protecting

consumers. Over the past six years, the Bureau has not only done a tremendous amount to protect consumers against predatory

financial practices and foster fairer industry practices, it has also secured about $12 billion in relief for 29 million consumers, including

$400 million dollars returned back to consumers that have fallen victims of fair lending abuses.

86

Beyond the billions returned to consumers through enforcement actions, the CFPB has introduced strong new mortgage disclosure

forms, has helped millions of consumers through its consumer complaint portal and has conducted research and outreach to millions of

people so they better understand their finances and can access good financial products. All of these and other Bureau functions have

gone a long way toward improving consumer financial markets and rectifying the predatory lending practices that were rampant before

the financial crisis. Unfortunately, despite the Bureau’s high level of effectiveness, numerous efforts have been undertaken to

undermine the only watchdog on the side of everyday consumers. Given that communities of color and other vulnerable populations

are often the victims of unfair, deceptive and predatory practices, we need to ensure that the CFPB is maintained as an independent

and effective government agency.

Stop Wealth-Stripping Practices: In recent years, there has been a resurgence of predatory and wealth-stripping scams, many backed

by large Wall Street firms. These include the return of “contract for deed” transactions that preyed on Black homebuyers excluded by

traditional government-backed mortgage lenders in the 1950s and 60s. Contract for deed transactions are sale agreements in which the

seller finances the transaction. CFDs are not inherently predatory, but opportunities for abuse are plentiful. Most CFDs are not recorded

nor subject to the Truth in Lending Act and other consumer protections enjoyed by most traditional mortgage borrowers. Under a CFD

arrangement, the buyer has all of the responsibilities and headaches of a homeowner, including making repairs, paying property taxes

and securing insurance, without actually owning anything. These buyers have even fewer rights than the typical renter, who can at least

call the landlord to fix a busted toilet or broken lock.

87

To mitigate the risk for abuse associated with these transactions, state laws should ensure that until buyers have all the rights of

homeownership, they at least have the protections afforded to tenants. The National Consumer Law Center has suggested a number of

public policies that states could implement to stem the tide of growing CFD abuses. One reform would be to require sellers using a land

contract to stop pushing provisions that require buyers to make repairs in order to make the house habitable. It is unfair that a buyer

who doesn’t even hold the deed to a property is saddled with the responsibility of expensive repairs. This reform would eliminate one of

the driving forces behind Wall Street firms pushing land contracts—the ability to manipulate low-income buyers into providing an

income stream to investors while shouldering all the burdens of home repairs.

88

At the federal level, although the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) cannot alter state property laws, it could issue

regulations requiring CFD transactions to abide by consumer protection laws against deceptive practices. In May 2016, six members of

Congress, led by Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), wrote to CFPB Director Richard Cordray, “Because CFDs can lead to increased debt,

financial instability and eviction for hard-working American Families,” the Bureau should “examine the use of CFDs and determine how

the Bureau may provide consumer protections to cover these transactions.” Shortly after this request, the CFPB began investigating

Harbour Portfolio—a company sued by the City of Cincinnati in 2017 for “intentionally fail[ing] to disclose known defects about

properties, including building code order and other violations.” In February 2017, a federal judge ordered Harbour to comply with the

Bureau’s subpoena for documents.

89

Finally, as federal lawmakers have already called for, the Federal Housing Finance Agency should stop Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the

two mortgage-finance companies in federal conservatorship, from selling foreclosed homes to firms such as Vision Properties and

Harbour Portfolio that are engaged in predatory CFD practices.

90

Conclusion

More than 50 years ago, at the March on Washington, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. began his famous “I Have a Dream” with an account of

the state of African Americans 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation. In those initial and often-forgotten words, Dr. King not