THE JAMAICA EDUCATION

TRANSFORMATION COMMISSION

THE REFORM

OF EDUCATION

in Jamaica, 2021

Presented to

Prime Minister the Most Honourable Andrew Holness, ON, PC, MP

by Professor the Honourable Orlando Patterson, OM, Chairman

JANUARY 2022

ABRIDGED VERSION

THE JAMAICA EDUCATION

TRANSFORMATION COMMISSION

THE REFORM

OF EDUCATION

in Jamaica, 2021

Presented to

Prime Minister the Most Honourable Andrew Holness, ON, PC, MP

by Professor the Honourable Orlando Patterson, OM, Chairman

JANUARY 2022

Disclaimer: This is a working report and is not for citation without permission

until

the final version is presented.

ABRIDGED VERSION

1 | Page

Report of the Jamaica Education Transformation Commission

Abridged Version

Preface

An Institution in Crisis

Jamaica has long struggled to overcome the twin challenges of economic stagnation and social

instability. As the Most Honourable Prime Minister, Andrew Holness, recently noted in his Emancipation

Day speech, these challenges are deeply rooted in our violent and exploitative colonial past. There is

now general agreement that the key to overcoming these problems is a well-functioning system of

education. It is the primary engine of social and economic growth. For individuals, it generates the

increased income that promotes social mobility and wellbeing; it produces the skills, knowledge, and

modes of thinking our economy, polity and social institutions need; and it promotes the values that

nourish our national culture, civil society and stability. We have known this from the first day of our

independence, and successive governments have, with admirable bipartisanship, devoted increasing

attention and resources to its development. There is no better indication of how highly we prioritize

education than the fact that, today, Jamaica is among the top 20 percent of nations in the share of its

national income and annual government budget devoted to this sector.

However, the education institution on which we have pinned so many of our hopes, both as individuals

and as a nation, is itself now entangled in three major crises. It has failed to educate a majority of

children in what the World Bank calls a ‘learning crisis’; it faces an administrative crisis of organizational

and strategic incoherence, redundancy and unaccountability, leading to chronic inefficiency; and it is in

the midst of the crisis brought on by the COVID 19 pandemic.

There have been successes. Jamaica claims to have one of the highest enrolments of pre-primary

children in the world. Access to education is now available to all children of primary school age and to

the great majority of adolescents. Our top secondary schools compare with the best in the world, and

the lead universities of our tertiary sector have produced women and men of the highest calibre. And

it is thanks to our schools that our small nation now amazes the world with the prowess of our athletes.

The institution of the ISSA Boys’ and Girls’ Athletics Championships, the complete creation of our

schools, is our greatest national event, the theatre of our civic pride, and the cathartic, if temporary,

healing of our many self-inflicted wounds.

But there have been enduring failures, partly emphasized by these very successes. The high

performance of our top 10 percent of schools, in demonstrating what might be possible, highlights the

inadequacies and inequities of the system. The global success of our young athletes exposes in bold

relief the large number of our youth who are unattached from employment, school, security and hope.

But our greatest failure lies in the very success of placing the great majority of our children in schools

where, sadly, the hopes of over a half are dashed by the end of their primary education from which

they emerge illiterate and innumerate.

2 | Page

The Prime Minister’s terms of reference to our Commission can be summed up in this single charge:

recommend the guidelines to correct this chronic failure in the institution to which we have devoted

so much of our national resources and energy. In doing so, however, we were immediately faced with

the global Covid-19 pandemic. As all the commission members have noted, COVID has magnified the

many shortcomings and inequities in the system. However, the timing of the commission made it

difficult to thoroughly study its impact: a full accounting is still to be known, and the data to measure

its damage yet to be collected. Nonetheless, to the degree possible the Commission has tracked its

influence and has recognized that its impact has been devastating. The majority of our students have

likely missed at least a half a school year of quality learning, and a substantial minority with limited or

no access to online learning have possibly lost more than a year. Behind the devastation, there were

silver linings such as the rapid learning of online teaching and the provision of internet resources. The

Teaching and Curriculum committee, in particular, has also found that the crisis has led to a greater

awareness and appreciation of the role of teachers and of the importance of parents, the local

community and out-of-school factors for the efficient running of our schools. These unexpected gains

have informed many of our recommendations, which indicate the ways in which what was learned, of

necessity, can be maintained and better built when life returns to normalcy.

However, there is no gainsaying the fact that the pandemic has been an educational calamity from

which it will take a long time to recover. It is therefore the worst possible time for the nation to face

the mounting institutional crises in the ministry responsible for dealing with the educational havoc

brought on our children by the pandemic.

Among our terms of reference is an assessment of the outcomes of the many admirable

recommendations of the 2004 Task Force on Education. Our assessments are given at length in the

reports of the various sub-committees of the Commission, especially those of Governance and of

Teaching and Curriculum. In broad terms, while the 2004 task force made many valuable

recommendations toward improvement of the teaching profession and classroom procedure directly

relating to student performance, in the implementation process these were largely neglected or failed

to make much of an impact. Instead, the emphasis during implementation was on the building of

institutional capacity, which was effectively executed by the Education System Transformation

Program. These upstream changes are yet to have any meaningful effects on the academic

performance of our students, the majority of whom continue to perform at well below the goals and

standards set by the Task Force itself as well as later national plans such as the 2009 Vision 2030 Jamaica

National Development Plan of the Planning Institute of Jamaica, and the 2012 National Education

Strategic Plan of the MoEYI.

The 2004 Task Force also strongly recommended institutional changes in the MoEYI, hardly any of which

were implemented, as noted by the report of our Governance committee. Mindful of these

implementation deficiencies and their consequences, the Commission has placed primary emphases

on the institutional reform of the Ministry, and on teaching and curriculum reform, the longest sections

of our report. The Commission has also highlighted the foundational early childhood development

sector, which was not considered in the 2004 Task Force report. This commission further differs from

that of 2004 in its consideration of the tertiary sector, which it concludes needs major reform.

The members of the Commission were honoured to have been given this extremely important task and

all worked diligently to fulfil its mandate. The fact that we were forced by the pandemic to meet online

3 | Page

turned out to be an advantage, since it allowed for far more meetings and a more efficient use of time

in our deliberations. It also meant that we were able to hear the views of a larger than usual number of

stakeholders. I am happy to report that all members of the Jamaican community we called upon were

willing to share their views and expertise with us and clearly saw it as the fulfilment of their civic duty.

A substantial number of persons went further, agreeing to be co-opted by the sub-committees and

collaborating on a regular basis for the entire course of our work. We also benefited from the advice

and work of several members of international organizations related to Jamaica, chief among whom

were Ms. Cynthia Hobbs, Lead Education Specialist and Dr. Diether Beuermann Mendoza, Lead

Economist, both of the Inter-American Development Bank; Ms. Mariko Kagoshima and Dr. Rebecca

Tortello, Country Representative and Education Specialist, respectively, of UNICEF Jamaica; and Mr.

Shawn Powers, Economist of the World Bank Group’s Latin American and Caribbean Unit. Of special

value was UNICEF’s survey of the nation’s students on behalf of the Commission, which provided us

with a detailed account of what students think and feel about their education and the changes they

would like to see implemented, changes we are happy to report, comported well with our own findings

and recommendations.

The Commission was provided invaluable assistance by its secretariat, ably directed by Ms. Trudy Deans,

Senior Advisor to the Prime Minister. Two other senior members of the Prime Minister’s office, Mr.

Alok Jain, Consultant, and Ms. Merle Donaldson, Chief of Staff, also gave us critical advice throughout

the year. Our work would not have been possible without the cooperation of the officers of the Ministry

of Education and Youth who provided us with the answers and data that we sought. The Honourable

Minister of Education, Ms. Fayval Williams, has enthusiastically supported the aims and work of the

Commission, not only meeting on several occasions with the group, but engaging in long conversations

with me from which I greatly benefited.

Speaking personally, I would like to thank the Most Honourable Prime Minister for the confidence he

has shown in me in my appointment as Chair of the Commission. I am deeply honoured to have been

given this opportunity to serve my country in such a critical endeavour. Nearly fifty years ago, in 1972,

I was appointed by the then recently elected Prime Minister, the Honourable Michael Manley, to serve

as his Special Advisor for Social Policy and Development. Prime Minister Holness, at our first meeting,

reminded me that 1972 was the year of his birth. The fact that I have been able to serve two Prime

Ministers so far apart in age and political philosophy reflects one of our greatest assets as a nation: the

steadfast vibrancy and continuity of our democratic system of governance. Our system of education

has also greatly benefited from this continuity, in the unusual degree of bipartisanship shown by our

political leaders in supporting and reforming the institution over the course of our history as an

independent nation.

Despite this bipartisan effort, however, the performance of the system has been deeply unsatisfactory,

failing too many of our nation’s children. It is our ardent hope that the successful implementation of

our recommendations will justify, finally, this sustained effort by our leaders to achieve the ideal

expressed in the Vision 2030 National Development Plan which is modified as follows: ‘equitable access

to modern education and successful training appropriate to the needs of each person and the nation’.

Professor the Honourable Orlando Patterson, O.M.

Chair, Jamaica Education Transformation Commission: 2020. Office of the Prime Minister, Jamaica

John Cowles Professor of Sociology, Harvard University

4 | Page

MEMBERS OF THE JAMAICA EDUCATION TRANSFORMATION COMMISSION

Chair: Professor the Honourable Orlando Patterson, O.M. - John Cowles Professor of Sociology,

Harvard University

Committee Chairs:

• Dr. Dana Morris Dixon, Chair, Governance and Accountability and Tertiary Committees

Assistant General Manager/Chief Marketing and Business Development Officer, Jamaica National

Group Limited

• Mr. Jeffrey Hall, Co-Chair, Finance Committee - Chief Executive Officer, Jamaica Producers Group

Limited

• Ms. Floretta Plummer, Chair, Technical and Vocational Education and Training Committee

Former Principal, Naggo Head Primary School

• Ms. Erica Simmons, Chair, Infrastructure and Technology Committee

Executive Director, Centre for Digital Innovation and Advanced Manufacturing, Caribbean Maritime

University

• Prof. Michael Taylor, Chair, Teaching and Curriculum Committee - Dean of the Faculty of Science and

Technology, UWI Mona

• Prof. David Tennant, Co-Chair, Finance Committee

Professor of Development Finance and Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences, UWI Mona

Members of the Commission

• Dr. Garth Anderson, Principal, Church Teachers College

• Prof. Eleanor Brown, Professor of Law and International Affairs, Pennsylvania State University

• Prof. Colin Gyles, Acting President, University of Technology, Jamaica

• Most Rev. Donald Reece, Archbishop Emeritus of Kingston and Chairman, Ecumenical Education

Committee

• Prof. Maureen Samms-Vaughn, Professor of Child Health, Child Development and Behaviour, UWI

Mona

• Mr. Gordon Swaby, Chief Executive Officer, EduFocal Limited

• Mrs. Esther Tyson, Former Principal, Ardenne High School

• Ms. Trudy Deans, Senior Advisor to the Prime Minister

5 | Page

Contents

Preface ................................................................................................................................................... 1

Members of the Jamaica Education Transformation Commission ........................................................ 4

List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 6

List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................... 6

Introduction: Guiding Principles ............................................................................................................ 7

The Findings of the Commission .......................................................................................................... 11

1. The State of Education in Jamaica ............................................................................................... 11

1.1 The Performance of Students ................................................................................................ 12

1.2 The World Bank’s Report on Jamaica’s Learning Crisis and declining Human Capital Index

(HCI) ............................................................................................................................................. 14

1.3 The Performance of Schools, with a New Method of Evaluation

.......................................... 14

2. Governance and Accountability ................................................................................................... 18

3. Early Childhood Education ........................................................................................................... 26

4. Teaching, Curriculum and Teacher Training ................................................................................ 29

5. The Tertiary Sector ....................................................................................................................... 50

6. TVET in Jamaica ............................................................................................................................ 55

7. Infrastructure and Technology .................................................................................................... 55

8. Finance ......................................................................................................................................... 58

How Jamaican Students Re-Imagine their Education .......................................................................... 63

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................... 64

Appendices .......................................................................................................................................... 66

Appendix 1: List of Acronyms .......................................................................................................... 66

Appendix 2: How the Report was Produced—The Consultation and Collaborative Process ........... 67

Appendix 3: Co-opted Members – Subcommittees ......................................................................... 72

Vision ............................................................................................................................................... 73

6 | Page

List of Figures

Figure 1 CSEC Certificate Pass Rate by Years and Gender ................................................................... 12

Figure 2 Performance of boys and girls in primary level exams .......................................................... 13

Figure 3 The Instructional Core ............................................................................................................ 31

Figure 4 Summary of career paths and options ................................................................................... 33

Figure 5 Distribution of Teachers by Qualification in Infant, Primary and Secondary Schools

(2018/2019). ........................................................................................................................................ 35

Figure 6 Government expenditure on education as a share of the GDP (%), 2017 or latest ................ 59

Figure 7 Government expenditure on education as a share of the total government expenditure (%),

2017 or latest ....................................................................................................................................... 59

Figure 8 Jamaica and benchmark countries. Per-student expenditure as a share of GDP per capita (%),

2015 or latest ....................................................................................................................................... 59

Figure 9: Latin America and the Caribbean (selected countries): TVET related payroll tax revenues,

2017 (percentages of GDP) .................................................................................................................. 60

Figure 10 Jamaica and benchmark countries. Expenditure composition by economic classification,

2016 or latest ....................................................................................................................................... 61

Figure 11 Jamaica. Expenditure composition by economic classification, 2018/19 and 2019/20 or

latest .................................................................................................................................................... 61

List of Tables

Table 1 Pass Levels and Overall Pass/Fail Ratios in the 2019 PEP Examinations ................................. 12

Table 2 Rankings of Average & Value-Added Scores for CSEC & CAPE Exams + Base % Average Results

(Traditional Schools 2001-2018) .......................................................................................................... 16

Table 3 Rankings of Average and Value-Added Scores for CSEC & CAPE + Base % Average Results ..... 17

Table 4 Review of Performance of Supporting Entities within the Ministry of Education, Youth and

Information .......................................................................................................................................... 21

Table 5 Highest Education Qualification of ECI Staff ........................................................................... 27

Table 6 Reasons for children not staying in school prior to Grade 11 (by area and by per capita

consumption quintile group) ............................................................................................................... 46

7 | Page

Introduction: Guiding Principles

Access to education has long been enshrined as a fundamental human right, its provision by most

countries hailed as one of the great achievements of the late 20th century. However, there is growing

awareness of the fact that access to schooling does not amount to learning and that in many parts of

the developing world children at the end of primary education remain illiterate. This learning crisis is

costly both in terms of human and economic development, UNESCO estimating that it costs

governments some $129 Billion dollars per year.

1

Jamaica, unfortunately, is typical of the learning crisis.

We therefore follow UNESCO in its declaration that:

“Children do not only have the right to be in school, but also to learn while there, and to emerge

with the skills they need to find secure, well-paid work.”

The pursuit of this fundamental right animates the work and recommendations of this report. Although

Jamaica has a good record in providing near universal access to primary school, it has failed to educate

at the most basic level a substantial proportion of its children. Exam results in 2019 indicated that at

the end of 6 years of primary schooling 59 percent were failing mathematics, and 45 percent were

failing in language arts. Jamaica’s tepid economic performance over the past half century, not to

mention its related chronic social problems, can in good part be attributed to its learning crisis.

Five fundamental principles motivate our objectives and recommendations for the reform of Jamaica’s

education system: organizational coherence in the governance of education, internal and external

systemic alignment in its functioning, a pedagogic transformation focused on the instructional core of

learning as a collaborative process, a revision of the curriculum grounded in the complementary

learning of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, the ARTS, and Mathematics) and SEL (Social and

Emotional Learning) disciplines, and the vigorous pursuit of equity.

A. Organizational Coherence

Organizational coherence exists when all parts of the education system work toward successful learning

outcomes. Jamaica has a chronic coherence problem, in which different parts of the system work at

cross purposes with each other, in the process neglecting or undermining the ultimate goal of learning.

These organizational problems were clearly recognized by the 2004 Task Force and recommendations

made to correct them. Nonetheless, there has been a failure to deliver improved outcomes in student

performance, in spite of considerable capital investment, very high prioritization of education in the

nation’s budget, and a great deal of capacity building over the past two decades. Two experts on the

problem of coherence have indicated what needs to be done to fix this problem: “There is only one way

to achieve greater coherence, and that is through purposeful action and interaction, working on

capacity, clarity, precision of practice, transparency, monitoring of progress, and continuous correction.

All of this requires the right mixture of “pressure and support”: the press for progress within supportive

and focused cultures”.

2

The Commission hopes to achieve such coherence in the organization of

education in Jamaica.

1

UNESCO: Teaching and Learning: Achieving Quality for All. EFA Global Monitoring Report 2014.

2

M. Fullan and J. Quinn, 2015. Coherence: The Right Drivers in Action for Schools, Districts, and Systems.p.2

8 | Page

B.

Systemic Alignment

Alignment is the interdependent functioning of the different levels of the education system with each

other, and of the system with its economic and social environment. Internal alignment is the efficient

coordination of the different levels of the education system. We may think of the entire education

system as a learning stream in which value is added at each level, depending in part on the degree and

quality of the input from the previous level. Jamaica’s globally competitive school athletic program is a

stellar case of successful alignment. Its underfunding of the foundational pre-primary level is an

unfortunate example of misalignment, being a major cause of the learning crisis appearing in its primary

and secondary levels.

External alignment is the collaborative process of orchestrating the educational system with the

demands of the private sector and broader societal needs. It is a strategic approach to educational

planning and programming in which leaders at all levels of the education system “strategizes, aligns,

collaborates and implements with the private sector for greater scale, sustainability, and effectiveness

in achieving development or humanitarian outcomes across all sectors.”

3

Jamaica’s education has long

failed to provide the nation with a badly needed skilled labour force, the Vision 2030 National

Development Plan noting that nearly 70 percent of the workforce had received no formal training and

that its tertiary sector is “not sufficiently responsive to the demands of the labour market.” The

alignment is a two-way process and there are encouraging recent signs that the Jamaican private sector

is ready to engage in such educational co-leadership and co-investments such as the National Baking

Company Foundation’s support of scholarships in science, the NCB Foundation’s sponsorship of digital

training in schools, and the Amber group’s recent digital training school. The Commission strongly

recommends the advancement of such educational co-investments modelled on the practice of long-

established apprenticeship countries such as Germany, Denmark, Switzerland and Korea.

C.

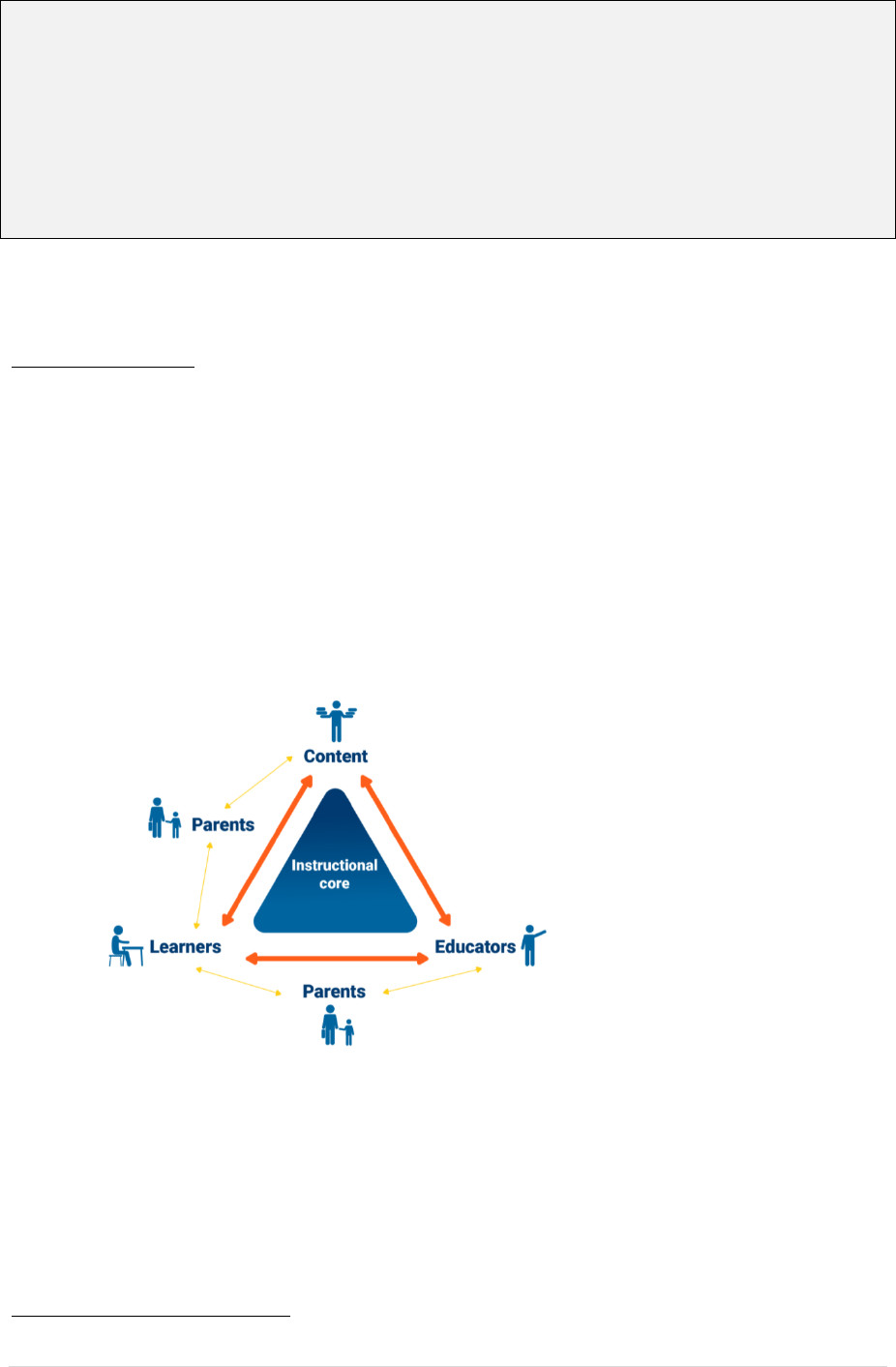

Collaborative learning focused on an interactive instructional Core

The Commission finds that Jamaica’s teaching profession is too committed to a traditional, teacher-

centred method of instruction aimed at passive students, which discourages learning. We advocate a

radical shift toward a pedagogical method in which the instructional core is a collaborative interaction

between flexible teachers, engaged students and a dynamically relevant curriculum. Research shows

that teachers’ instructional capacity varies with their interaction with students and how they use the

materials; and the experience, prior knowledge, modes of thinking, disposition and relations with other

students are as critical to what and how students learn as what the teachers impart of the curriculum

being taught: “Improved capacity depends on affecting the ways in which teachers, students and

materials understand, make sense of, and influence one another.”

4

To the degree possible, this

interaction should include the supportive role of parents and other care-givers. This approach has

important implications for how teachers are trained as well as their later development, for both periods

of which the classroom should be central. It entails a substantial makeover of teaching colleges and the

retraining of trainers at these institutions. Such reform asks much of teachers, which is why we affirm

UNESCO’s recommendation that “governments must provide teachers with the right mix of incentives

to encourage them to remain in the profession and to make sure all children are learning, regardless of

their circumstances.” We applaud the fact that the MoEYI’s new National Standard Curriculum

embraces elements of this approach, but we regret its failure to properly prepare and train teachers

and students for it. We strongly urge the Ministry to start over, and recommend measures to get it

3

Lisa Blonder, 2020. “What does Private Sector Engagement Mean in Education.” USAID. https://www.edu-

links.org/learning/whatdoes-private-sector-engagement-mean-education

4

David Cohen and Deborah Ball, “Instruction, Capacity and Improvement”, Penn Grad School of Educ,

Consortium for Policy Research and Improvement, 1999

9 | Page

right. The commissioners were greatly encouraged by the findings of a UNICEF survey, prepared for the

Commission, that Jamaica’s schoolchildren all share these views on learning, and appeal for more

teacher-student collaboration, active engagement, more parent and teacher motivation, and blended

learning.

D.

An Appropriate Curriculum

The Jamaican education system faces two major challenges: the need to train students to function in a

technologically based economy; and the need to help solve its catastrophic problem of crime, including

unusual levels of violence toward females, children and persons with non-traditional sexual and gender

orientations. Hence, the curriculum requires as much attention to social and emotional learning as to

STEAM so as to engender respect for human life and a sense of responsibility and civility in human

relations.

Our move toward a more technologically driven and knowledge-based system requires the

incorporation of a STEAM curriculum at all levels of the education system. However, this equally

necessitates a shift toward a SEL curriculum. Emotionally unstable, disrespectful, educationally

disengaged children cannot learn STEAM. However, the good news, from a wealth of educational

research, is that the teaching and learning of STEAM education and SEL are complementary and

mutually reinforcive.

5

The collaborative classroom built around the respectful interaction of teacher,

student and relevant content required by STEAM is precisely the kind of pedagogy that cultivates the

mutual respect, self and social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making that are

the goals of social and emotional learning. The work of Professor Marina Bers, who addressed our

Commission, and has agreed to work with us, has compellingly demonstrated this interaction in her

studies and policy work with pre-schoolers.

6

In the reform of the curriculum, it is important to pay full attention to our history. Few societies bear

the stamp of its past more than Jamaica and its history should be one cornerstone of learning at all

levels. The ‘A’ in STEAM must stand as much for “Annals’ as for Arts.

E.

Equity

UNESCO has noted that: ‘Equity is at the core of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).’

Educational disparity is chronic in the island, considerably worsened by the pandemic. There are two

extremely different school systems in the country, one that is world-class and serves mainly the ‘Haves,’

the other, pertaining to the vast majority, that serves the ‘Have-Nots’ and that is largely failing. Jamaica

also has a gender problem, but unlike most of the rest of the world, it is boys who are at a disadvantage.

This peculiar gender problem is directly related to the crisis of unattached youth, gangs, and violence.

This, we hasten to add, is not the result of positively favouring girls, but of the special social

circumstances faced by boys, their often-abusive upbringing, and the cultural norms of masculinity from

the compelling popular culture that too often disincentivizes education. Indeed, Jamaican girls and

women pay a high price for this male failure, reflected in unusually high rates of sexual abuse by men

from an early age, and the fact that they experience the highest rate of femicide (homicide, nearly all

by men) in the world.

5

Peterson, A., Gaskill, M. & Cordova, J. (2018). Connecting STEM with Social Emotional Learning (SEL)

Curriculum in Elementary Education. In E. Langran & J. Borup (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information

Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 1212-1219)

6

Strawhacker, Amanda; Bers, Marina Umaschi, 2018. “Promoting Positive Technological Development in a

Kindergarten Makerspace: A Qualitative Case Study,” European Journal of STEM Education, v3 n3 Article 9

10 | Page

There is also a poorly addressed problem of disability in the country, with woefully inadequate

resources made available to students with special needs. We strongly endorse the UNICEF’s inclusive

education benchmark norms that require the inclusion of children with disabilities in regular schools

wherever possible, and the removal of all physical and instructional barriers to them.

International studies by PISA show definitively that the vigorous pursuit of equity is not a drag on high

educational performance, that, to the contrary, “fairness in resource allocation is not only important

for equity in education, but it is also related to the performance of the education system as a whole…

school systems with high student performance in mathematics tend to allocate resources more

equitably between advantaged and disadvantaged schools.” We are mindful that equity and the

provision or equal resources are not the same, that indeed, the latter may exacerbate the former. The

Commission therefore strongly endorses the International Commission on Education’s policy of

“progressive universalism,” which advocates “expanding provision of quality education for everyone

while prioritizing the needs of the poor and disadvantaged.”

7

Conclusion

The best laid plans are only as good as their implementation. We recognize that there is a serious

implementation deficiency in Jamaica. To ensure success we urge the government to heed the advice

of those who have studied the problems of implementation. First and foremost, that the ownership

and commitment to the changes we recommend are assumed by both the Minister and other top

leaders of the Ministry of Education and, following their example, at all levels of the organisation down

to school administrators and teachers. Above all, top leadership must buy into our plan and not simply

announce and applaud it then return to business as usual, which is the sure recipe for failure. Secondly,

that there is an unwavering commitment to accountability on the part of those enjoined with the

implementation of our recommendations throughout the implementation period. Thirdly, that

managers in the MoEYI are all clear about the nature and prioritization of our recommendations, and

that they are thoroughly communicated and understood. Fourthly, that there is constant monitoring

and review of how our recommendations play out in practice, with unhesitating action to correct what

does not work, to be replaced with what does achieve the recommended goal, in a continuous process

of improvement. Fifthly, that the necessary resources and management capabilities are assigned to the

implementation of our plan, with changes in allocation as realities on the ground dictate during the

implementation process. Finally, and most importantly, we urge the government to consider locating

the implementation of our recommendations outside of the administrative framework of the Ministry

of Education. Given the failure to implement the institutional recommendations of the 2004 Task Force

and the institutional crises now facing the Ministry, we do not believe that it is capable of internally

reforming itself.

We are all fully committed to Jamaica’s noble motto for education, that “every child can learn, every

child must learn.” However, this ideal will never be attained until we overcome our chronic pattern of

implementation deficiency. The Jamaica Education Transformation Commission hopes to change this

pattern and do well by our children, the disadvantaged among whom have waited far too long for

change.

7

The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity, 2016. The Learning Generation:

Investing in Education for a Changing World, pp. 87-88

11 | Page

The Findings of the Commission

The Jamaica Education Transformation Commission was launched in July 2020 by the Most Honourable

Prime Minister, Mr. Andrew Holness, charged with conducting a ‘comprehensive review of the public

education system, covering all sectors of education, namely, early childhood, primary, secondary,

vocational, and higher education.’ On the basis of this review, it should recommend an action plan for

change setting out ‘specific legislative, policy, structural or other changes necessary to create a world-

class educational system, geared to enabling Jamaicans to fulfil their potential and develop the skill

base and human capital required for Jamaica to compete successfully in the 21st Century Global

Economy.’ Over the course of the past eleven months, the fourteen members of the Commission, with

the valuable assistance of several co-opted members and a dedicated secretariat, produced this

document. This document summarises the full findings and recommendations of the Commission,

which can be found in a companion document (the Unabridged Version).

The Commission’s work focused on eight (8) areas of the education system: An Analysis of the Present

State of Education in Jamaica; Governance; Early Childhood Education; Teaching, Curriculum and

Teacher Training; the Tertiary Sector, Technical and Vocational Education and Training; Infrastructure

and Technology; and Finance. The recommendations for each of these eight areas are included at the

end of each section, though detailed explanations and recommendations may be found in the extended

version of the JETC report. Care must be taken not to treat the recommendations of this report in ‘silos’,

since this runs the danger of neglecting the principle of organizational coherence, the fact that the

system is highly inter-related and that recommendations made in one area directly or indirectly impact

another.

Following these sections, we summarize the results of a survey of Jamaican students’ views on the

education system and their recommendations for change which was generously produced on our

behalf by UNICEF Jamaica in 2021.

1. The State of Education in Jamaica

The education system is one of the largest institutions in Jamaica. The Ministry of Education, with its

eleven agencies and 7 regional offices, employs over 25,000 teachers who educate nearly 580,000

students in over a thousand educational centres. Jamaica provides access to education to nearly all

children of pre-primary and primary ages and to the majority of those in the secondary school cohorts

18 and under.

At the pre-primary level Jamaica claims one of the highest rates of enrolment in the world: 93.4% of 3–

5-year-old children, the great majority in private institutions that are not effectively monitored, with

most providing unsatisfactory care. At the primary level some 232,000 students are registered.

Although the country claims to offer universal access, UNESCO reports a gross enrolment rate of 85%

and a net rate of 79% which is well below those of countries at Jamaica’s level of development and of

the other small Caribbean states. Furthermore, over 17% of primary age children are not in school, due

mainly to economic factors (lunch money and transportation fare) and boredom.

Some 211,800 students attend secondary schools. Jamaica’s officially stated secondary enrolment rates

are also problematic. Contrary to the 98 percent rate recently reported to the World Bank, the lower

and upper secondary rate (ages 12-16) is 87%, and for age groups 17 and 18 (grades 12 & 13) it is 28.7%.

Most students leave secondary school without a certificate—70 percent of the 18-year-old cohort in

12 | Page

2018. As of 2018, there were 51,684 students in the tertiary level, attending 18 institutions, of which 3

are universities. The island’s tertiary rate of enrolment is 27%- well below that of countries at its level

of development.

1.1 The Performance of Students

Although the great majority of its children have access to primary and secondary schooling, Jamaica has

a severe learning crisis, in that a majority of students at the end of primary school remain illiterate and

innumerate and most leave secondary school with no marketable skills. In 2017, over 85% of students

achieved “mastery” of their Grade 4 literacy test, and 66% in their test of numeracy. Although there

were indications of improvement between 2002 and 2018 in the GSAT and GNAT primary school-

leaving exams, the recently introduced PEP (Primary Exit Profile) exam, which shifted away from

memorized learning to the testing of analytic thinking, revealed major deficiencies in the level of

learning achieved by students: only 41% passed in mathematics, 49% in science, and 55% in language

arts (Table 1). A breakdown of the language arts results indicated that a third of students at the end of

primary school could not read, 56% could not write, and 57% could not identify information in a simple

sentence.

Table 1 Pass Levels and Overall Pass/Fail Ratios in the 2019 PEP Examinations

Subject

Percent

Beginning

Percent

Developing

Percent

Proficient

Percent Highly

Proficient

Pass/ Fail

Ratio

Math

7

52

35

6

41/59

Science

7

44

42

7

49/51

Social Studies

3

34

50

13

63/37

Language Arts

9

36

46

9

55/45

The PEP exam indicated that most students were barely literate. The mean language score in the last

GSAT exam in 2018 was 65. While the two exams are not strictly comparable, the GSAT score indicated

at least acceptable levels of literacy. However, the PEP exam showed that: 33% of students could not

read or barely do so, 56% could not write or barely able, and 58% could not find information on a topic

in a simple passage.

Performance at the end of secondary schooling was not much better. In 2019 some 32,617 students

sat the CSEC exams (54% females/45% males), of which only 42.5% passed 5 or more subjects including

English and/or mathematics. Overall, only 28% passed 5 or more subjects with English and

Mathematics. In the CAPE exams, pass rates are low and have been declining: only 45% passed the

Diploma certificate at an acceptable level.

Figure 1 CSEC Certificate Pass Rate by Years and Gender

13 | Page

In all examinations, starting with the

Grade 4 tests, girls substantially out-

perform boys (Figure 1). The gap

appeared to decline somewhat

between 2005 and 2018 in the primary

and secondary school tests but

increased sharply with the new PEP

exams in 2019, in which girls

outperformed boys by 15 points in

Mathematics, by 13 points in science, by

20 points in Language arts, and by 13

points in social studies. Jamaica is one of

the few countries where girls

outperform boys in math and science.

Figure 2 Performance of boys and girls in primary

level exams

The performance of students at the tertiary level will be examined in depth in the Tertiary section of

this report. We note here, however, that the gender disparity widens at each level of the system. At

the tertiary level, 69% of enrolled students are females, and only 31% are males. Women also

graduate from this level at three times the rate of men.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

Mathematics Science Language Arts Social Studies

Performance of boys and girls in primary level

exams

% of Boys Failing % of Girls Failing

14 | Page

1.2 The World Bank’s Report on Jamaica’s Learning Crisis and declining

Human Capital Index (HCI)

The World Bank’s most recent Human Capital Reports

8

indicate that Jamaica has a learning crisis of

relatively high enrolment and poor education performance that is getting worse, contributing to its

deteriorating Human Development Index score. In 2018, the Bank found that children in Jamaica could

expect to complete 11.7 years of pre-primary (starting at age 4), primary and secondary schooling by

age 18. However, when years of schooling were adjusted for quality of learning, it was found that this

was equivalent to only 7.2 years, a learning gap of 4.5 years. This gap is a major component of the

Bank’s overall Human Capital Index (HCI), which measures the amount of human capital that a child

born today can expect to attain by age 18. It ranges between 0 and 1. A country with a score of 1 means

that a child born today can expect to achieve complete education and full health by age 18. Jamaica’s

Human Capital Index in 2018 was .54, ranking it in the bottom half of countries, significantly below its

Caribbean small-island counterparts as well as the average for the upper-middle income group of

countries to which it belongs.

Since then, the country’s score and rank have declined, due mainly to its relatively poor education

performance. In 2020, assessed before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Bank found that Jamaican children

could expect to complete 11.4 years of schooling by the age of 18. However, factoring in what children

actually learned, the actual years of schooling were only 7.1 years, a gap of 4.3 years, the slight decline

in the gap due to the facts that both the expected and adjusted years of schooling had declined.

Jamaica’s overall Human Capital Index has also declined to .53, which means that a child born in Jamaica

today will be 53 percent as productive when they grow up as they could be if they had achieved

complete education and full health. Jamaica’s country rank on the Human Capital Index has worsened

to 97

th

out of the 173 countries assessed, worse than the average of its income group as well as the

group of small Caribbean countries.

1.3 The Performance of Schools, with a New Method of Evaluation

Schools cannot be blamed entirely for the unsatisfactory performance of the nation’s students, but

they bear a good deal of responsibility for it. Jamaica now has two ways of evaluating the performance

of schools. One is by the National Education Inspectorate, instituted in 2009, which uses traditional

means of evaluation—observations, tests, self-evaluations and the like. The other was introduced in

2021 by this Commission, applying only to secondary schools: a value-added mode of evaluation, on

the basis of which a novel composite ranking system was constructed.

In 2015, its most recent nation-wide evaluation, the National Education Inspectorate evaluated 55% of

schools as ‘ineffective,’ with 45% of school leaders judged “unsatisfactory” and only 55% of teachers

assessed as “satisfactory or above.” Since then, there has been dramatic, though inexplicable,

improvements in the NEI’s evaluation indicators. However, no nationwide evaluations similar to the

baseline of 2015 have since been done.

Value-added estimates measure how much of students’ examination performance can be attributed to

the school itself as distinct from the attributes of the students and their background. Jamaican

secondary schools were ranked, not solely on the basis of their exam results, or only on the value-added

8

The World Bank, The Human Capital Index, 2018 & 2020

file:///C:/Users/orp295/Downloads/9781464815522.pdf

https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/363661540826242921/pdf/The-Human-Capital-Project.pdf

15 | Page

metrics, but also with a new composite index, created by the Commission, that combined the average

of rankings on both exam results and value added results.

Stakeholders still have the option to continue using only exam results to assess schools should they so

choose. In view of the extreme inequality of schools in Jamaica, the Commission decided to divide the

secondary schools into two groups: a traditional, more privileged, group of 42 schools and a non-

traditional group of 211 schools. Unfortunately, it was not possible to conduct the value-added

procedure on 100 of the secondary schools because of either missing data or the fact that their exam

results were at zero percent pass rate which confounds modelling.

Tables 3 and 4 show the rankings for the 42 traditional, and top 42 non-traditional high schools. The

complete list of all schools, including the 100 which were not included in the value-added model, but

with CSEC and CAPE results attached, can be found in the Unabridged Version of the Commission’s

report. The results substantially alter the traditional evaluation of the nation’s secondary schools. The

nation’s top three traditional secondary schools, measured in terms of the composite ranking index,

are Glenmuir High School, in May Pen, Wolmer’s High School for Girls in Kingston, and St. Jago High

school in Spanish Town. The three top non-traditional high schools are Dinthill Technical in Linstead,

Denbigh High in May Pen, and Edwin Allen High in Frankfield. Merl Grove High school and Campion High

are the best performing traditional high schools measured solely in terms of the value they add based,

respectively, on the CSEC and CAPE exams. St. Mary’s College and Bluefields High/Belmont Academy

are the best non-traditional performers in value added based, respectively, on the CSEC and CAPE

results.

Glenmuir emerges as the nation’s preeminent secondary school. It clearly demonstrates that schools

can perform at the highest level while admitting students from more modest backgrounds, or those

who may not have been as well prepared academically during their primary school years.

Moving Forward: Recommendations on the Evaluation of Secondary Schools

EVAL1: Standardise the us of the value-added ranking for secondary schools

EVAL1.1: It is recommended that in future years all secondary schools should be evaluated and

ranked using the value-added procedure, complementing the traditional evaluation of the

National Education Inspectorate

EVAL1.2: The value-added rankings should be combined with the rankings on the regular CSEC

and CAPE exams to produce the composite rank developed by the Commission

EVAL1.3: MoEYI should promptly address both sets of evaluations. Special attention should be

paid to schools that perform poorly on the value-added assessment. Schools that perform well

should be publicly acknowledged and rewarded

EVAL1.4: Both sets of evaluations should be made publicly available and widely disseminated

to stakeholders

EVAL1.5: Every effort should be made to ensure that all schools are able to provide the

appropriate data needed to conduct the value-added procedure

16 | Page

Table 2 Rankings of Average & Value-Added Scores for CSEC & CAPE Exams + Base % Average Results (Traditional Schools

2001-2018)

Seco nd ar y Sch o o l

Name

OVERALL RANKING Based

on Average of All Other

Rankings

Ranking based on Average

Result (% CSEC

Certificate)

Ranking based on Added

Value (% CSEC Certificate)

Ranking based on Average

Result (VA CSEC and %

CSEC Certificate)

Ranking based on Average

Result (% CAPE Diploma)

Ranking based on Added

Value (% CAPE Diploma)

Ranking based on Average

Result (VA CAPE and CAPE

Diploma)

Average CSEC %

Certificate

Average CAPE % Diploma

GLEN M UI R HI GH SCHOO L

1 3 16 1 4 3 4 72.04% 46.55%

WOLM ERS HIGH SCHOOL FOR GIRLS

2 6 24 9 3 2 2 69.86% 52.01%

ST JA G O H I G H SC H O O L

3 15 12 7 8 5 7 62.13% 38.87%

ST A N D REW H I G H SC H O O L F O R GI RLS

4 5 17 3 11 15 12 71.42% 34.32%

IMMACULATE CONCEPTION

4 2 35 16 2 4 3 72.89% 54.26%

CAM P I O N CO LLEGE

6 1 41 22 1 1 1 73.64% 64.15%

WOLM ERS BOYS HIGH

7 8 30 17 6 7 7 68.81% 43.43%

CO N VEN T O F M ERCY

8 22 11 13 12 9 9 58.69% 31.26%

HAMPTON HIGH

9 4 37 30 5 6 5 71.50% 45.86%

QUEENS HIGH SCHOOL

10 28 8 15 15 8 10 52.76% 28.90%

ST H U GH S H I GH SCH O O L

11 23 5 8 20 14 16 57.21% 27.47%

ARDENNE HIGH SCHOOL

12 7 33 19 7 13 8 69.17% 39.66%

CLA REND O N CO LLEGE

13 32 3 14 23 11 16 48.02% 26.88%

MEADOWBROOK HIGH

14 25 6 10 21 19 19 56.30% 27.14%

KINGSTON COLLEGE

15 19 14 13 19 20 18 61.32% 27.78%

HOLY CHILDHOOD HIGH

16 17 9 6 26 23 26 61.88% 26.12%

WESTWOOD HIGH

17 10 22 11 13 31 22 68.22% 30.88%

ST H I L D A S D I O C EA N

18 13 13 6 26 23 26 63.63% 26.15%

KNOX COLLEGE

19 18 4 3 29 29 31 61.47% 24.00%

DECARTERET

20 16 29 25 17 16 14 61.89% 28.66%

ST M A RY H I G H SCH O O L

21 31 19 32 16 10 12 51.79% 28.71%

MERL GROVE HIGH SCHOOL

22 24 1 4 32 27 32 56.37% 21.02%

MANNINGS SCHOOL

23 11 36 30 14 25 18 64.56% 30.57%

ST C A TH ER I N E H I G H SCH O O L

24 38 7 25 31 12 21 40.97% 21.27%

MUNRO COLLEGE

25 20 39 36 9 18 13 61.22% 36.23%

MORANT BAY HIGH SCHOOL

26 27 15 21.5 28 21 26 53.49% 24.96%

MONTEGO BAY HIGH SCHOOL

27 9 38 30 10 32 20 68.62% 34.73%

MOUNT ALVERNIA HIGH SCHOOL

28 12 27 18 22 34 29 63.74% 27.05%

ST G EO RG ES CO LLEG E

29 26 20 27.5 24 22 23 56.08% 26.19%

CH ARLEM O N T H I GH SCH O O L

30 41 2 23 37 17 28 31.87% 17.12%

BISHOP GIBSON HIGH SCHOOL

31 21 26 30 18 30 24 59.27% 27.95%

MARYMOUNT HIGH SCHOOL

32 35 10 25 35 26 33 44.07% 18.01%

MANCHESTER HIGH SCHOOL

33 14 32 27.5 27 35 34 63.05% 25.49%

TI TCHFI ELD HI GH SCHOOL

34 33 21 33.5 33 24 30 46.88% 18.96%

CAM P ERD O W N H I GH SCH O O L

35 36 18 33.5 39 33 36 43.59% 16.64%

YO RK CA ST LE H I G H SCH O O L

36 30 25 35 36 37 38 52.09% 17.47%

CO RN W ALL CO LLEGE

37 29 40 41 30 41 35 52.56% 21.50%

JA M AI CA CO LLEGE

38 34 34 39.5 34 39 38 45.16% 18.28%

EX CEL SI O R H I G H SC H O O L

39 39 28 38 41 36 40 38.11% 13.38%

CALABA R H I GH SCH O O L

40 37 31 39.5 38 38 39 42.57% 16.87%

FERNCOURT HI GH SCHOOL

41 42 23 37 42 42 42 30.43% 7.26%

RU SEAS H I GH SCHO O L

42 40 42 42 40 40 41 33.95% 13.42%

17 | Page

Table 3 Rankings of Average and Value-Added Scores for CSEC & CAPE + Base % Average Results

Secondary School Name

Ranking based on Average Result

(All rankings)

Ranking based on Average Result

(% CSEC Certificate)

Ranking based on Added Value

(%CSEC

Certificate)

Ranking based on Average Result

(VA CSEC and % CSEC Certificate)

Ranking based on Average Result

(% CAPE Diploma)

Ranking based on Added Value (%

CAPE Diploma): 2SLS

Ranking based on Average Result

(VA CAPE and % CAPE Diploma)

Average %CSEC Ce

rtificate

Average % CAPE Diploma

DINTHILL TECHNICAL SCHOOL

1

7

4

1.5

4

3

2

31.90%

13.16%

DENBIGH HIGH SCHOOL

2

2

9

1.5

3

16

5

41.10%

14.71%

EDWIN ALLEN HIGH SCHOOL

3

9

11

5

5

12

4

27.40%

11.74%

ST MARYS COLLEGE

4

15

1

4

11

11

6

23.64%

9.02%

OLD HARBOUR HIGH SCHOOL

5

13

2

3

15

19

9

25.36%

8.01%

THE CEDAR GROVE ACADEMY

6

12

15

7

25.54%

HOLMWOOD TECHNICAL HIGH SCHOOL

7

27

6

10

25

6

8

18.83%

4.51%

JONATHAN GRANT HIGH

8

11

18

8

13

24

10

26.31%

8.19%

JOSE MARTI TECHNICAL SCHOOL

9

28

27

20

9

4

3

18.60%

10.13%

MACGRATH HIGH SCHOOL

10

40

5

13.5

18

10

7

13.24%

6.26%

OBERLIN HIGH SCHOOL

11

16

16

9

14

28

12

23.55%

8.05%

GUYS HILL HIGH SCHOOL

12

33

12

13.5

21

17

11

15.63%

5.68%

VERE TECHNICAL HIGH SCHOOL

13

20

3

6

20

51

14

21.56%

5.75%

GARVEY MACEO HIGH SCHOOL

14

17

17

11

12

75

18

23.28%

8.64%

HOLLAND HIGH SCHOOL

15

18

31

17

17

59

16

22.75%

7.49%

MICO PRACTISING PRIMARY AND JUNIOR HIGH

16

51

10

23

43

30

15

10.43%

2.47%

CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL

17

42

23

26

32

46

17

12.54%

3.54%

SPALDINGS HIGH SCHOOL

18

19

20

12

22

94

26

21.99%

5.17%

BLUEFIELDS HIGH / BELMONT ACADEMY

19

14

144

69

1

1

1

24.48%

16.34%

BOG WALK HIGH SCHOOL

20

75

42

40

31

31

13

6.41%

3.64%

WINDWARD ROAD PRIMARY AND JUNIOR HIGH

21

64

8

28

69

42

23.5

7.91%

1.04%

ST MARY TECHNICAL HIGH

22

25

37

24.5

24

101

28

19.30%

4.70%

BRIDGEPORT HIGH SCHOOL

23

21

41

24.5

16

119

34.5

21.29%

7.62%

MAY DAY HIGH SCHOOL

24

10

36

15

19

137

48.5

26.67%

5.83%

SYDNEY PAGON AGRICULTURAL HIGH SCHOOL

25

90

7

36

4.68%

ANNOTTO BAY HIGH SCHOOL

26

32

19

18

44

113

50

16.09%

2.23%

MILE GULLY HIGH SCHOOL

27

35

54

33

30

99

30

14.42%

3.73%

LENNON HIGH SCHOOL

28

45

26

27

36

109

40

11.52%

2.97%

NEW DAY PRIMARY AND JUNIOR HIGH

29

113

14

45

105

2

21

2.83%

0.48%

CLAUDE MCKAY HIGH SCHOOL

30

56

38

34

38

102

37

9.56%

2.69%

ST THOMAS TECHNICAL HIGH SCHOOL

31

29

24

19

26

155

69

18.22%

4.47%

CONSTANT SPRING PRIMARY AND JUNIOR HIGH

32

114

30

56.5

97

7

20

2.77%

0.57%

IONA HIGH SCHOOL

33

26

48

29

28

138

56

19.25%

4.16%

TIVOLI GARDENS HIGH SCHOOL

34

77

61

50.5

57

60

27

5.95%

1.56%

MAVIS BANK VOCATIONAL SCHOOL

35

95

28

44

90

45

34.5

4.35%

0.66%

AABUTHNOTT GALLIMORE HIGH SCHOOL

36

37

49

31

48

118

56

13.80%

1.98%

BUFF BAY HIGH SCHOOL

37

50

59

37

52

98

44

10.54%

1.76%

HOLY TRINITY HIGH SCHOOL

38

100

52

63

77

33

22

4.14%

0.83%

TACKY HIGH SCHOOL

39

66

64

47

65

73

36

7.76%

1.21%

ST ANDREW TECHNICAL HIGH SCHOOL

40

38

117

65.5

27

84

23.5

13.60%

4.30%

WATERFORD HIGH SCHOOL

41

92

46

50.5

72

62

33

4.62%

0.95%

PORT ANTONIO HIGH SCHOOL

42

36

45

30

49

132

69

13.82%

1.95%

18 | Page

2. Governance and Accountability

Good governance is a critical element of any well-functioning education system. The current

governance framework is inadequate for the articulated goal of significantly improving education

outcomes in Jamaica. As noted before, the Government of Jamaica (GOJ) is committing significant

resources to education, but the returns are well below what is acceptable. This disconnect between

spend and results is due in large part to the lack of accountability across the system as well as issues in

the administration of the education system.

The GOJ has dedicated significant resources to the development of a corporate governance framework

for public bodies and this framework has been implemented across most Ministries, Departments and

Agencies. The GOJ’s corporate governance framework is predicated on the premise that better

governance leads to better outcomes, more efficient spend and enhanced strategic focus. The

Committee is of the view that the education system should adopt these corporate governance norms

that emphasize accountability and transparency, and which ultimately facilitate key values of inclusivity

and equity in education.

Decisions regarding the use of funds in the sector, channels of accountability, and agenda setting—all

related to governance—impact the overall effectiveness of an education system. Ensuring quality

education is therefore dependent on the existence of good governance and relies on the five principles

of:

• legitimacy and voice

• performance

• fairness

• accountability; and

• direction

9

In the area of Governance, the Commission focused its work on a review of the overall governance

framework for the education system. The key elements of this review included the Ministry’s structure

and the effectiveness of the strategic framework of the Ministry, school boards, and the various

agencies tasked with supporting the work of the MoEYI.

The OECD argues that effective governance requires that a government sets “clear distribution of roles

and responsibilities and find the right balance between central and local direction, set concrete

objectives and policy priorities for their education system, and engage stakeholders in the process.”

10

While there is some evidence locally of efforts to engage stakeholders in processes of setting priorities

for the system, too often balances between local and central direction and clear distribution of

responsibilities (such as between the central ministry and regional offices and the schools themselves)

have fallen flat or have been hindered by incoherent strategies. Improved governance and new

mechanisms to pursue effective governance are desperately needed as the country seeks to address

these challenges and create a more effective education system.

9

Graham J, Amos B and Plumptre T (2003) Principles for Good Governance in the 21st Century. Ottawa,

Canada: Institute on Governance in Hutton, Disraeli M. "Governance, management and accountability: The

experience of the school system in the English-speaking Caribbean countries." Policy Futures in Education 13,

no. 4 (2015): 500-517.

10

https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/4581cb4den/index.html?itemId=/content/component/4581cb4d-en

19 | Page

MoEYI Strategic Planning

The Commission also found that the MoEYI was deficient in its strategy setting as its overarching policies

often lacked strategic focus and coherence. In addition, the accountability structures were lacking at all

levels and this accountability deficit has negative implications for the country’s ability to improve its

education outcomes. As one of the largest and most critical public employers and service providers, it

is important for the Ministry of Education to have and routinely monitor a coherent strategic plan.

Furthermore, that strategic plan must be linked to the performance of the Ministry’s management

team, with mechanisms in place to measure achievements against expected outcomes.

Following the report of the 2004 Task Force for Education Reform, the Government of Jamaica designed

a National Education Sector Plan (2011-2020) (NESP) which outlined targets for the Ministry of

Education and actors within the education system to meet through to 2020. Though the targets

outlined in the plan are time-bound (ranging from goals to be achieved from 2015 to 2020), the plan

lacked specific details on the short-term targets to be implemented, or variables used to measure the

achievement of outlined targets,

leaving clear doubts on the Ministry’s capacity to monitor its progress

in achieving these targets

.

The NESP listed the relevant pieces of existing legislation and the additional legislative and policy

changes that would be required to meet the strategic objectives set. Of that list of twenty-two (22)

necessary changes prescribed in 2011, as of July 2021, only three (3) have been passed with some

policies underway. Based on the Commission’s review of this plan, and other business, operational, and

strategic plans of the Ministry, it is evident that there is no consistent monitoring or articulation of

progress being made on targets set for Vision 2030 in the NESP, or annually in the various strategic

plans, given that:

i. there exists a plethora of targets and strategies that are misaligned and overlapping;

ii. the strategies and annual targets to be met are not publicly communicated; and

iii. the progress made by relevant actors for all targets are not consistently measured.

Organisational Structure of the MoEYI

Data on staffing and organisational structure provided by the ministry show that the organisation is

extremely complex with a very large number of staff. Based on the data made available to the

Committee from the Ministry, it appears that most funds allocated to the central ministry relate to

compensation with smaller amounts available for programmatic activities that could have impact.

Furthermore, the committee found that the seven (7) educational regions are not organised and

resourced to achieve the goals articulated in the 2004 Taskforce Report, despite being equipped with

additional human resources. However, there is still a very high school-to-staff ratio as the regions are

grossly understaffed. There is also a need for reform of the education officer function to lessen the

administrative duties so that these valuable resources can focus on improvements within the schools.

Given the vast budget allocated to the sector and the significant performance challenges

it is important

that a comprehensive organisational review be conducted of the central ministry and the regions at a

minimum

. During both official and informal interviews, the committee also unearthed concerns

regarding the cultural dynamics in the Ministry as well as the lack of appropriate accountability

structures in the Ministry.

20 | Page

Organisation structures need to be designed with clear guidance from the Strategy and Policy direction,

consideration for the current context (e.g. severe under-resourcing, out-dated technology, unfilled

vacancies, etc.), to address organisational imperatives (e.g. the need for rapid transition from manual

to automated workflows, use of on-line platforms for teaching, need to deliver sustainability and Vision

2030 goals, regulations) and principles (e.g. guidelines for handling staff changes arising from

recommendations, developing talent, etc.). Once these considerations are established, the design will

require a close examination of the “FROM” position to the “TO” state and interdependencies in the

following key areas: Strategy, Technology, Processes, Governance/Risks, Talent Capability, Talent

Capacity and Culture among others. Once these parameters are understood the organisation can be

reviewed and re-designed with the support of research, practical tools, analysis and change

management as recommendations are developed.

Poor Performance of School Boards

Currently, school boards are appointed by the responsible Minister to serve for a three-year period

pursuant to Regulation 79. There is no minimum qualification for an individual to be nominated to serve

on a board. In addition, this service is voluntary, and members are not remunerated for their service.

There is an imbalance in the availability of qualified and competent representatives. As seen in some

boards, there may not be sufficient members that fully understand the impact of their decisions on the

administration, faculty, ancillary staff, or the student body.

Lack of Data Analysis

A key requirement of a functioning administrative apparatus is the existence of a robust system of data

collection and analysis. In a modern school environment data must be at the heart of strategy setting

and overall decision-making. Good data analytics allows for increased operational efficiency and is an

indispensable source for making decisions, formulating diagnoses about strengths and weaknesses of

institutions, and assessing the effects of initiatives and policies.

11

The MoEYI has not been a participant

in this data revolution, but if we want to improve outcomes the creation of a data analytics unit is

imperative as it will allow for increased operational efficiency in the MoEYI. It will also allow the MoEYI

to make better assessments of its institutions and in turn formulate more evidence-based educational

policies.

Education Management System

A 2019 review of Jamaica’s current Education Management Information System (EMIS) concluded that

it was deficient in several areas.

It concluded that the Jamaican EMIS is in an “incipient” state of

development

(2.07) which meant that it partially covers the processes and structural conditions that

define it but is not geared to efficient management. Also, there is currently no complete student

directory that covers all levels and uses the School-Education Programme-Section-Student

identification paradigm to identify the school, curriculum, and section to which each student belongs.

For teachers' professional development plans, the MoEYI has yet to establish full digital support and

monitoring systems.

11

Agasisti, T. and Bowers, A. (2017). Data analytics and decision-making in education: Towards the educational

data scientist as a key actor in schools and higher education institutions. Retrieved from

https://www.academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8K374FG/download&ved=2ahUKEwja-

7SPnNXxAhUpneAKHefPBJQQFjAaegQIExAC&usg=AOvVaw0X2b1mlQUs-EBG3bOQYhM

21 | Page

Inadequate Monitoring and Evaluation

The Programme Monitoring and Evaluation Unit (PMEU) of the MoEYI was established in the Planning

and Development Division of the MoEYI to monitor and evaluate programmes and projects introduced

and/or being utilized by the Ministry, as well as inform the relevant stakeholders on the progress

thereof and indicate ways in which the programmes can be improved. The work of the Unit in terms of

evaluation is lacking in the evaluation of student outcomes as seen by its evaluation of the National

Standards Curriculum (NSC). The narrative therefore outlines the need for a more improved, robust

Monitoring and Evaluation Unit which will aid in setting performance goals, selecting useful

performance indicators and targets, reporting on results, and informing the implementation of

programs. There also needs to be greater planning so that gaps can be observed between the planned

and achieved results.

There are several agencies supporting the MoEYI in achieving its goals

and objectives, the Committee reviewed these entities with a focus on

those created after the 2004 Taskforce Report. The general view is that

these institutions are operating at world class standards and should be

commended. These include the UCJ and the NEI. The following table

summarises the review of the performance of the remaining entities:

Table 4 Review of Performance of Supporting Entities within the Ministry of Education, Youth and Information

Entity

Function

Performance

Indicators

University Council of

Jamaica

Registers and assures the quality of local programmes

and institutions, and foreign programmes being offered

in Jamaica.

National Education

Inspectorate

Assesses the standards attained by the students within

primary and secondary schools at key points in their

education, generate a report on the findings and make

recommendations to support improvements.

Early Childhood

Commission

Coordinates all activities, development plans and

programmes within the early childhood sector.

Jamaica Tertiary

Education

Commission

To regulate, standardize, safeguard and transform

Jamaica's tertiary education sector.

National Parenting

Support Commission

Coordinates parenting support programmes.

22 | Page

Overseas

Examinations

Commission

Supervises overseas examination boards at the

secondary and tertiary level.

Jamaica Teaching

Council

Responsible for the enhancement and maintenance of

professional standards in teaching.

National College for

Educational

Leadership

Responsible for preparing school leaders for effective

leadership

Jamaica Library

Service

Provides information, educational and recreational

programmes and services through a Public Library

Network and School Library Network.

National Council on

Education

Ensures effective governance of public educational

institutions.

National Education

Trust

Mobilizes financial and quality resource investments for

schools

Nutritional Products

Limited

Produces and distributes meals to schools.

Urgent Need for Amended Regulations

Currently, the education sector is governed by the Education Act and Education Regulations which was

promulgated in 1965 and 1980, respectively. However, the standing legislative framework does not

contemplate the current educational landscape and its rapid transformation.

This has created a lacuna

in the educational sector because the multiplicity of powers bestowed upon the education minister

cannot be effectively utilised based on the existing legislative framework

.

It is important to further note

that none of the proposed legislative amendments in the 2004 Report have been drafted or implemented

in the Regulations

: This includes the School Improvement Bill, the Jamaica Teaching Council Bill, the

Jamaica Tertiary Education Commission Bill, and the long-awaited amendments to the 1980 Education

Regulations. There have been years of discussion regarding these amendments, but there has been

little progress in passing them. The Committee recommends a complete re-write of the Education Code

in the medium term, but given the GOJ’s less than stellar performance in relation to legislative matters,

the Committee concluded that at a minimum, the Education Code should be amended with focus on

the priority areas for amendment as outlined in Version 1 of the JETC’s report. The Governance and

Accountability Committee spent copious amounts of time reviewing the Discussion Draft of the

Proposed Amendments to the Education Regulations, 1980 that was produced in 2019.

The key areas of amendment to the Regulations were grouped into six (6) headings:

– Accountability

– Teacher Performance

23 | Page

– Technology

– Health & Safety

– Early Childhood Provisions

– Elimination of Discriminatory Policies

As seen in this summary of some of the deficiencies in the governance and accountability framework