1 | P a g e

September 17, 2019

VIA Electronic Upload and Hand Delivery

Comment Intake – Debt Collection

Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection

1700 G Street, NW

Washington, DC 20552

Re: ACA International, the Association of Credit & Collection Professionals,

(“ACA”) Comment to Docket No. CFPB-2019-0022, RIN 3170-AA41

Dear Director Kraninger and Bureau staff:

The Association of Credit and Collection Professionals (“ACA International” or

“ACA”) appreciates the time and attention that you will spend reviewing and

considering our comments to the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection’s

(“CFPB” or “Bureau”) Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) to implement the

Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA). The Bureau’s proposed Regulation F

will be the first of its kind since the FDCPA was enacted in 1977. Accordingly, the

CFPB’s proposal will shape the future of the industry and the larger economy. ACA

members have long sought clarity surrounding the use of new technologies,

including several that are now decades old, that have altered how consumers

communicate from the time more than 40 years ago when the FDCPA was first

enacted.

To prepare the following comments, ACA conducted quantitative and qualitative

studies of our membership. This included interviewing dozens of small, medium,

and large collection agencies, as well as service providers. Members of the accounts

receivable management industry have provided ACA written and verbal feedback

and suggestions on all aspects of Proposed Regulation F. Further, ACA called upon

its members to collect data, which we have aggregated and anonymized to support

our observations and suggestions. At ACA’s national meeting in July 2019, ACA

convened panels, roundtables, and other discussions so that members of the

P a g e | 2

accounts receivable management industry could express their views on the

Proposed Regulation.

1

Since the Bureau’s inception, ACA members have worked

diligently to provide it data and feedback about rulemaking proposals, collaborate

on compliance and financial education initiatives, and help it better understand the

benefits of two-way communication for consumers when facing an unpaid debt. ACA

members take their obligations to consumers when collecting debt very seriously,

and the input provided in this comment hopefully will provide a roadmap for how

the CFPB can improve its proposal, as we both work towards our shared pursuit of

improving consumer outcomes and ensuring that the accounts receivable

management industry has clear rules for operating.

Executive Summary

Overall, ACA believes that the Bureau’s efforts will resolve ambiguities in the

FDCPA and help create uniform national standards. This will address both

consumer and industry concerns by providing transparency to consumers seeking to

understand their rights under the law and decrease litigation over benign technical

errors. We appreciate the Bureau’s efforts to provide clarity to the practice of

sending electronic communications. The limited content message is also a common-

sense solution for both consumers and industry to address a statutory catch-22,

which has harmed the ability to leave voicemail messages, increased call volumes,

and has warranted regulatory guidance for several decades. The Bureau’s proposal

for a model form validation notice to address the plethora of ambiguities in FDCPA

§809 concerning the validation of debts is also a step in the right direction toward

providing some important clarifications.

Nonetheless, as outlined in our comments, in several parts of its proposal the

Bureau attempts to add new requirements that impose significant burdens on the

accounts receivable management industry without any quantitative evidence of

consumer harm in those areas, and often with razor-thin research. Moreover, many

solutions lack empirical data to support their approach. Indeed, ACA’s studies

indicate that some Bureau proposals will cause enhanced consumer harm by

increasing incentives for creditors to file collection suits because aspects of the

Proposed Rule stymie their ability to settle debts outside of court.

1

Cmt. Dempsey, ACA International, Re. Ex Parte Filing, CFPB-2019-0022-1195 (07/23/2019).

P a g e | 3

ACA’s principal concerns fall into several broad categories:

• Meaningful communication must not be discouraged through

arbitrary limitations on call frequency. The work of the accounts

receivable management industry allows consumers and creditors to settle

debts outside of litigation. Therefore, any regulation that interferes with

meaningful communication between collectors and consumers will increase

debt collection litigation.

2

Thus, we are concerned when Regulation F

provisions create arbitrary and capricious barriers to communication.

Communication barriers include, “call caps” at §1006.21, complicated E-sign

3

consents at §1006.42, vague inconvenient place and time restrictions at

§1006.6(b)(1) and (6)(b)(1)-1, and work email address restrictions at

1006.22(f)(3). ACA warns that evidence from states with overreaching

regulations proves that if collectors cannot communicate, creditors will

litigate.

• Itemization in the validation notice will be impossible for many,

would cost over $ 3 billion to initially implement and will increase

litigation. Approximately three-quarters of the accounts receivable

management industry will struggle to comply with the itemization

requirement at §1006.34 because they service non-finance debt. Non-finance

debts are accounts originated by businesses such as hospitals, doctors,

dentists, health clubs, pest control and lawn maintenance services, and

telecommunications. Some non-financial creditors also include state

governments, local governments and municipalities, utilities, and even the

Internal Revenue Service. Many businesses have historically provided

sufficient documentation and itemization to prove the existence of a debt in

state courts. However, they often do not maintain account data in the fashion

contemplated under the rule. We estimate that the cost to change creditor

systems to comply with §1006.34 will be in the billions. Moreover, the Bureau

has not studied whether creditors can alter their data collection practices,

and makes questionable assumptions that creditors can (and will) make

alterations without a regulatory directive.

2

See infra, Chapter One section IV.

3

Section 104 of the Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act (E-SIGN Act), 15

U.S.C. § 7004.

P a g e | 4

• The U.S. economy depends on collected debt. Debt collection returned

$67.6 billion of funds in 2016 to US businesses—that’s an average savings of

$579 for every American household. Regulations should not incentivize

consumers to shirk legal and valid debts at the expense of honest businesses

and other consumers seeking affordable credit. Small and medium-sized

business owners and their employees will stop providing services in advance

of payment if collections become less certain. Rules that could so severely

impact the U.S. economy must be tested and substantiated with econometrics

and cost-benefit analyses. The Bureau has not yet performed these studies.

• New rules should not hold the accounts receivable management

industry liable for attempting to discern unclear or ambiguous

consumer information. Several Proposed Rule sections require collectors to

divine facts by holding collectors liable when they “should know”: whether an

email is a “work” address (1006.22(f)(3)); if the consumer’s name has a suffix

(1006.34(c)(2)(ii); the consumer’s sleep, work, or school schedule

(1006.6(b)(1)); the consumers’ legal defenses to the debt (1006.26(b)); that the

consumer paid another party (1006.27.(b)); or that the consumer has recently

died (1006.42). Historically, under the FDCPA, collectors are permitted to

rely on the information provided to them by the creditor, and the standard for

holding collectors liable is information for what collectors “have a reason to

know,” or “absent knowledge to the contrary.” Regulations that attempt to

increase this standard and ask collection agencies to be mind readers as to

the consumer’s private life will drive creditors and collectors towards

litigation instead of meaningful communication.

• To have a functioning credit-based economy in the United States,

consumers have some responsibility to pay their debts and to

participate in the discussions about how to pay them. Consumers

benefit when they take part in the process of resolving debt. Through open

communications, they can obtain the best results by working out payment

plans, fee waivers, identify other parties responsible for paying the debt, or

even defer payments if they are facing a hardship or are truly unable to

afford to repay the debt. If a consumer objects to contact by a certain method,

they have a plethora of rights to do so. If they have questions about payment

history, credits, or insurance payments, they should ask for more detail.

P a g e | 5

As CFPB Deputy Director Brian Johnson recently noted in remarks,

Contrary to common mythology, consumer credit—the process of lending

money to consumers—increases opportunity and wealth in the economy. A

consumer borrows money today and spends more in the present, with the

intent on paying back the loan in the future. Put differently, rather than

save over a period of time and forgo the benefits of a particular product,

consumer credit changes the timing of the purchase. Yet, government

regulators often ignore the basic purpose behind consumer use of credit.

They can fail to recognize that market transactions are a positive-sum

game. And they can also ignore the economic reality undergirding the

pricing and types of services offered by businesses.”

4

The ability to collect on unpaid debt is an important part of this process, and

the work of collection agencies has proven to keep the price of credit more

affordable for consumers.

• Clear and Plain Language Communication is Best for Consumers

and Industry. Despite the offensive rhetoric of certain interest groups, most

accounts receivable management industry professionals are fantastic people,

representing a diverse segment of the United States.

5

As part of their work,

they want to help consumers find a solution to their financial problems. But

fear of plaintiff’s litigation and the “overshadowing” doctrine force collection

agencies to use stiff and confusing statutory language that consumers deem

intimidating. Rule 1006.34 seeks to rationalize the policy behind the

overshadowing doctrine and clarify significant ambiguities in the FDCPA by

providing a single model form and a safe harbor. But some form language can

be better, and the form ought to allow flexibility for modifications

necessitated by state law or other legal requirements.

• The CFPB’s Complaint Database Data Paints an Inaccurate Portrait

of the Accounts Receivable Management industry. Throughout the

4

Johnson, Brian, Toward a 21st century approach to consumer protection, (Nov. 15, 2018), available at

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/toward-21st-century-approach-consumer-protection/

5

ACA, SMALL BUSINESS IN THE COLLECTIONS INDUSTRY IN 2019, (ACA International White Paper

April 2019), available at https://www.acainternational.org/assets/advocacy-resources/aca-wp-

smallbusiness-2019-002.pdf

P a g e | 6

comment, the Bureau refers to complaint data about the accounts receivable

management industry to justify new interventions. However, the Bureau’s

complaint data is flawed. The most troubling aspects of the complaint

database are: (1) the Bureau’s broad definition of a complaint, (2) the

Bureau’s failure to verify the accuracy of the complaints it receives, and 3)

that the number of complaints versus the number of contacts are not

standardized. Notably, debt collection complaints account for only 0.005% of

all consumer contacts made in a given year by the accounts receivable

management industry.

ABOUT ACA INTERNATIONAL

ACA International is the leading trade association for credit and collection

professionals. Founded in 1939, and with offices in Washington, D.C. and

Minneapolis, Minnesota, ACA represents approximately 2,500 members, including

credit grantors, third-party collection agencies, asset buyers, attorneys, and vendor

affiliates in an industry that employs more than 230,000 employees worldwide.

ACA members include the smallest of businesses that operate within a limited

geographic range of a single state, and the largest of publicly held, multinational

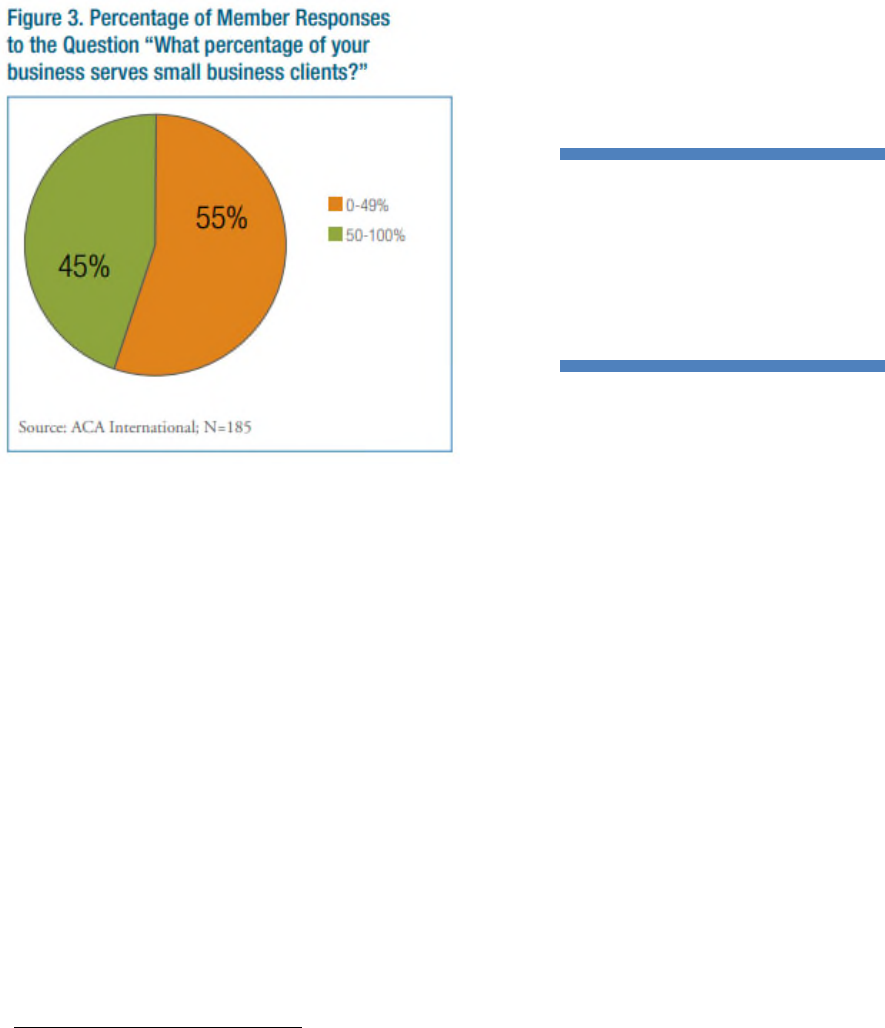

corporations that operate in every state. The majority of ACA-member debt

collection companies, however, are small businesses. According to a recent survey,

44 percent of ACA member organizations (831 companies) have fewer than nine

employees. About 85 percent of members (1,624 companies) have 49 or fewer

employees and 93 percent of members (1,784) have 99 or fewer employees.

As part of the process of attempting to recover outstanding payments, ACA

members are an extension of every community’s businesses. ACA members work

with these businesses, large and small, to obtain payment for the goods and services

already received by consumers. In years past, the combined effort of ACA members

has resulted in the annual recovery of billions of dollars – dollars that are returned

to and reinvested by businesses and dollars that would otherwise constitute losses

on the financial statements of those businesses. Without an effective collection

process, the economic viability of these businesses and, by extension, the American

economy in general, is threatened. Recovering rightfully-owed consumer debt

enables organizations to survive, helps prevent job losses, keeps credit, goods, and

services available, and reduces the need for tax increases to cover governmental

budget shortfalls.

P a g e | 7

An academic study about the impact of debt collection confirms the basic economic

reality that losses from uncollected debts are paid for by the consumers who meet

their credit obligations:

In a competitive market, losses from uncollected debts are

passed on to other consumers in the form of higher prices

and restricted access to credit; thus, excessive forbearance

from collecting debts is economically inefficient. Again, as

noted, collection activity influences on both the supply

and the demand of consumer credit. Although lax

collection efforts will increase the demand for credit by

consumers, the higher losses associated with lax collection

efforts will increase the costs of lending and thus raise the

price and reduce the supply of lending to all consumers,

especially higher-risk borrowers.

6

In short, consumer harm can result in several ways when unpaid debt is not

addressed, and ACA members work to help consumers understand their financial

situation and what can be done to address it and improve it.

The debt collection market is extremely varied in the types of debts being collected

and the nature and size of the accounts receivable management industry

encompasses a broad scope. Although the credit and collections industry comprises

a relatively small space in the entire consumer financial services arena, the client

base serviced by industry members is highly diverse, from large corporations to

local Main Street service providers — all of whom have a vested interest in

customer retention, particularly in the case of small business creditors. From

medical debt to student loan debt, mortgage debt to credit card debt, unpaid check

to unpaid government fees, or a single bill from a local business, the differences

incident to each type of debt require a thoughtful and nuanced regulatory approach.

6

Todd J. Zywicki, The Law and Economics of Consumer Debt Collection and Its

Regulation, MERCATUS WORKING PAPER, MERCATUS CTR AT GEORGE MASON UNIV., at

47 (Sep. 2015), available at https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/Zywicki-Debt-Collection.pdf.

P a g e | 8

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 2

ABOUT ACA INTERNATIONAL ................................................................................. 6

Chapter One- Overview and Studies ......................................................................... 16

I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 16

A. Significant Ambiguities in the FDCPA cause Unnecessary Litigation. ....... 17

B. Courts have developed FDCPA “Policy” without the Benefit of Regulatory

Tools ......................................................................................................................... 18

C. Regulatory Overreach in Regulation F Particularly Harms Small

Businesses ................................................................................................................ 20

1. Small Business Recommendations went Unaddressed ............................. 20

II. COMMENTS ON CONSUMER FOCUS GROUP STUDIES ........................... 23

A. Consumer Impressions don’t Equate to Violations. ...................................... 23

1. The Fors Marsh Study lacks a Robust Sample Set and Data Clarity ....... 25

2. Consumer Survey Evidence is Unreliable .................................................. 26

3. Legitimate Disputes Comprise Less than ½ Percent of All Accounts ....... 28

B. Calling Data Research .................................................................................... 29

III. DATA FROM STATE REGULATION ADVISES EXTREME RULEMAKING

CAUTION .................................................................................................................... 30

A. The 2015 New York DFS Debt Collection Rules Increased Collection

Litigation by 93% ..................................................................................................... 31

1. Itemization on Validation Notices .............................................................. 31

2. Disclosures About Debts for Which the Statutes of Limitations May be

Expired .................................................................................................................. 31

3. Increased Substantiation of Consumer Debts ............................................ 32

4. Debt Payment Procedures ........................................................................... 32

5. Communication through Email Restricted ................................................ 32

B. Over-Regulation of Communications Drives Creditors to Litigation ........... 33

IV. THE CFPB’S RELIANCE ON THE COMPLAINT DATA LACKS RIGOR .... 34

Chapter Two- Comments by Section .......................................................................... 35

P a g e | 9

I. COMMENTS ON §1006.2- DEFINITIONS ......................................................... 35

A. The Bureau’s Definitions Should Add More Certainty and Clarity ............. 35

B. Relevant Portions of Regulation F §1006.2 ................................................... 36

C. ACA’s Detailed Comments on §1006.2 Definitions ....................................... 37

D. The definition of “Attempt to Communicate” and “Communicate” .............. 37

1. These definitions may touch websites and other public displays of contact

information ........................................................................................................... 38

2. Regulation F “Communication” Should be Connected to Debt Collection 39

3. Collectors are unsure whether disconnected and wrong numbers are

“Attempts to Communicate” ................................................................................. 39

E. Inclusion of “whether living or deceased” in the definition of “consumer” is

not necessary to address the Bureau’s concerns. .................................................... 40

1. There is no evidence that supports including deceased persons in the

definition of consumer .......................................................................................... 40

2. The amendment imposes new uncertainty ................................................ 41

F. The “Limited-Content Message” is an Essential Modernization of the

FDCPA ...................................................................................................................... 41

1. When it comes to leaving messages, the FDCPA lacks clarity and is in

desperate need of interpretation. ......................................................................... 42

2. The “Limited Content Message” Resolves Ambiguity in the FDCPA Text ...

...................................................................................................................... 43

3. The Foti versus Zortman conundrum proves the need for agency

interpretation ........................................................................................................ 45

4. The Limited Content Message Definition Reconciles Conflicting

Approaches ............................................................................................................ 46

G. Additional Comments about the Limited Content Message ......................... 47

1. Limited Content Messages Should Allow Electronic Contacts ................. 47

2. Is there liability for inadvertent incomplete messages? ............................ 48

3. Provide clarification regarding consumer’s name ...................................... 48

4. More clarity is also needed surrounding the term “natural persons” ....... 49

5. Cost Concerns about Text Messages are Outdated ................................... 49

P a g e | 10

6. Additional clarity is also needed about direct drop voicemail programs. . 50

H. “Debt Collector” Ambiguities Can be Better Addressed ............................... 50

II. COMMENTS ON §1006.6 – COMMUNICATIONS IN CONNECTION WITH

DEBT COLLECTION .................................................................................................. 52

A. §1006.6(a) and Proposed Comments 6(a): The Definition of Consumer ....... 52

B. §1006.6(b)(1) and Proposed Comments (6)(b)(1)-1: Ascertaining

Inconvenience to the Consumer ............................................................................... 54

1. The CFPB Should Clarify the “Should Know” Standard Since a Collection

Firm must base it upon Limited Information from a Consumer about a Time or

Place being Inconvenient ...................................................................................... 54

2. Time and Inconvenience Restrictions Should Not Apply to Electronic

Communications ................................................................................................... 58

3. Collectors should be permitted to send email outside the presumptive

time limits ............................................................................................................. 59

4. The Accounts Receivable Management Industry should be permitted to

rely on the consumer’s address of record only for calculating timing of calls,

absent information to the contrary ...................................................................... 60

C. §1006.6(b)(2)(i): Clarifications Concerning the Length of Time an Attorney

Has to Respond to a Debt Collector ......................................................................... 61

D. §1006.6(b)(3) and Proposed Comment (6)(b)(3)-1: Prohibitions Concerning

the Consumer’s Place of Employment ..................................................................... 62

1. Clarity Is Needed Around When the Accounts Receivable Management

Industry Has Reason to Know That an Employer Prohibits the Consumer from

Receiving Debt Communications ......................................................................... 62

E. §1006.6(c)(1) and Proposed Comments 6(c)(1)-1: Notification Regarding

Refusal to Pay or Cease Communications............................................................... 62

1. The Proposed Rule Should Allow Additional Time for Processing a

Notification for Purposes of Determining When the Notice Goes into Effect .... 62

F. The Bona Fide Error Defense is only marginally referenced in § 1006.6(d)(1)

......................................................................................................................... 63

G. §1006.6(d)(3) and Proposed Comments – Reasonable Procedures for Email

and Text Message Communications to Avoid Communications with Third Parties .

......................................................................................................................... 64

P a g e | 11

1. The Bureau Should Clarify the Term “Recently” as Used in Proposed

§1006.6(d)(3)(i) ...................................................................................................... 65

2. The Accounts Receivable Management Industry Should Be Permitted to

Use Any Email Address or Phone Number That the Consumer Has Provided to

Contact the Consumer .......................................................................................... 65

3. The Time Periods Set Forth in Proposed §1006.6(d)(3)(i)(B)(1) Require

Further Clarification ............................................................................................ 66

H. Proposed §1006.6(e) – Opt-out For Electronic Communications .................. 67

1. The Bureau Should Clarify How to Differentiate Between an Opt-Out for

Electronic Communications and a Cease Communication Request Under

§1006.6(c)(1)(ii) ..................................................................................................... 67

2. Represented Party Contacts -§1006.6(b)(2) ................................................ 68

3. 1006.6(d)(1) -Limited Content Messages .................................................... 68

III. COMMENTS ON §1006.10 - ACQUISITION OF LOCATION INFORMATION

............................................................................................................................ 68

A. Acquisition of Location Information Generally ............................................. 69

B. Locating an Individual Who Can Resolve Decedent Debt ............................ 69

1. Collectors must be specific to be clear and understood ............................. 70

2. There is no reason to set stricter communication limits ........................... 71

IV. COMMENTS ON §1006.14(b)(2) – CALL FREQUENCY LIMITATIONS ...... 72

A. Positive Aspects of §1006.14(b) ...................................................................... 72

B. Proposed §1006.14(b) Exceeds the FDCPA’s Authority ................................ 72

1. FDCPA forbids calls with an “intent” to annoy, harass, or abuse ............. 73

2. §1006.14(b) bans clearly legal conduct ....................................................... 74

C. The Call Frequency Limits are Not Supported by Substantial Evidence .... 74

1. Frequency limits increase the cost and length of time to resolve debts ... 75

2. Frequency Limits fail to consider FCC actions .......................................... 75

3. The Prospect of "Unlimited Email and Text Messages" is a Chimera ...... 78

4. The One-Week Cooling Off Period is Impractical ...................................... 78

D. §1006.14(b) introduces new ambiguity to a regularly-occurring situation .. 80

P a g e | 12

E. An Aggressive Call Cap Requires Better Evidence than Shown to Support

its Implementation ................................................................................................... 80

V. COMMENTS ON §1006.14(h)- PROHIBITED COMMUNICATION MEDIA ... 81

VI. COMMENTS ON §1006.18(g)- MEANINGFUL ATTORNEY INVOLVEMENT

............................................................................................................................ 83

A. 1006.18(g)’s requirements are old-fashioned ................................................. 85

B. Proposed Rule 1006.18(g) Invades the Attorney-Client Relationship .......... 85

VII. COMMENT ON §1006.22 –UNFAIR OR UNCONSCIONABLE MEANS ...... 86

A. Consumers’ email communication preferences should be honored without

further permissions required ................................................................................... 87

1. §1006.22(f)(3) exceeds he commands of the FDCPA, which allows contacts

at work until the consumer expresses otherwise ................................................ 88

2. The “Should Know” standard will require new technology, will cost

Millions of Dollars and Cannot Be Perfect .......................................................... 88

3. §1006.22(f)(3) Lacks Evidence of a Reasonable Need ................................ 89

4. §1006.22(f)(3) is Paternalistic and Misguided ............................................ 89

B. §1006.22(f)(3) Will Chill Email Communications ......................................... 90

VIII. COMMENTS ON §1006.26- TIME-BARRED CLAIMS ................................ 91

A. Time-Bars are Complicated Legal Questions ................................................ 92

B. Legal Analysis can be done only by Lawyers ................................................ 94

C. The Bureau Should Propose Safe-Harbor Language .................................... 95

D. The Supreme Court Permits Time-barred Proofs of Claims ......................... 95

IX. COMMENTS ON §1006.30- CREDIT INFORMATION FURNISHING ......... 96

A. The FCRA Expressly Allows Furnishing after a Negative Reporting Notice

is provided ................................................................................................................ 97

B. Requiring the Accounts Receivable Management Industry to Communicate

with a Consumer Prior to Furnishing Information Regarding a Debt to Credit

Reporting Agencies Will Significantly Affect Business .......................................... 97

1. Passive Debt Collection is not a Widespread Practice ............................... 98

2. §1006.30 risks a shift in consumer behavior and economic incentives ..... 98

C. Accurate Credit Reporting Benefits Everyone ............................................ 100

P a g e | 13

D. The Bureau Should Clarify What is Sufficient to Establish

“Communication” and Whose Burden It Is to Establish That the Communication

Occurred ................................................................................................................. 100

1. A Safe Harbor is Necessary when Negative Notice is Provided .............. 101

2. “Attempts to Communicate” should be Sufficient .................................... 102

E. The Bureau Should Exempt Debt Collectors that Furnish Information to

Special Credit Reporting Agencies. ....................................................................... 102

X. COMMENTS ON §1006.34(c)- ITEMIZATION IN VALIDATION NOTICES . 104

A. The Bureau’s Proposal for Section 1006.34(c)(1) ......................................... 105

B. Itemization Requirements would Cost over $ 4 billion to Implement ........ 107

1. $600 million in one-time professional fees ............................................... 109

2. Over $30 million in one-time system reprogramming for agencies. ....... 109

3. Unknown $ billions annually in uncompensated medical care ............... 110

4. Costs to creditors will amount to over $ 3 billion. ................................... 111

5. On-going implementation and error-correction costs will continue. ....... 111

C. An Itemization Requirement would risk violating other federal law. ........ 112

D. Other Negative Consequences of Section 1006.34(c) .................................. 117

XI. COMMENTS ON §1006.34(C)(3)- FORM VALIDATION NOTICE. .............. 118

A. The Bureau’s Proposal for Section 1006.34 ................................................. 118

1. The CFPB’s model form must meet Chevron Step One by addressing

ambiguity in the FDCPA .................................................................................... 119

2. Ambiguities to be Addressed ..................................................................... 120

3. The Bureau’s Determination of Form Contents must be Detailed and

Reasoned ............................................................................................................. 123

C. “Clear and Conspicuous” Requirement in 1006.34(b)(1) is Not Suited to a

Conversation ........................................................................................................... 125

D. Conclusion ..................................................................................................... 125

XII. COMMENTS ON 1006.38 – DISPUTES AND REQUESTS FOR ORIGINAL

CREDITOR INFORMATION .................................................................................... 126

A. Duplicative Disputes .................................................................................... 126

P a g e | 14

B. Overshadowing ............................................................................................. 128

XIII. COMMENTS ON § 1006.42 - PROVIDING REQUIRED DISCLOSURES

ELECTRONICALLY ................................................................................................. 131

A. The Bureau Proposes to Allow Electronic Disclosures but Mandate E-SIGN

Act Consent ............................................................................................................ 132

B. The Bureau Should Reconsider and Reverse its View that the E-SIGN Act

Applies to the FDCPA’s Written Notices. ............................................................. 133

1. The Bureau’s Position on E-SIGN ............................................................ 133

2. The E-SIGN Act’s Language and History Do Not Compel the Bureau’s

Conclusion that Electronic Disclosures under the FDCPA Require E-SIGN

Consent. .............................................................................................................. 134

C. The E-SIGN Act Would Impose Substantial, Unnecessary Burdens in the

Context of Debt Collection. .................................................................................... 138

D. Even if the E-SIGN Act Applies, the Bureau Should Provide an E-Sign Act

Exemption for the FDCPA’s Written Notices. ...................................................... 139

1. Consent procedures are expensive ............................................................ 139

2. Consent Procedures are Confusing ........................................................... 140

3. The Deterrent Effect of Consent Procedures is Observed ....................... 140

E. ACA Urges the Bureau to Allow Required Disclosures both in the Body of an

Electronic Communication and in a Hyperlink without Onerous Limitations ... 143

F. ACA Urges Expansion of § 1006.42(e)’s Proposed Safe harbors ................. 144

G. The Bureau Must Urge the FCC to Provide Clarity on the Definition of

What is Considered an Autodialer for Text Messaging to be a Viable Option .... 145

XIV. COMMENTS ON §1006.100- RECORD RETENTION ............................... 145

A. The Bureau Should Narrow This Requirement to a Collector’s Last

Communication or Attempted Communication with a Consumer ....................... 146

1. Communication or Attempted Communication Definition Should Be

Clarified .............................................................................................................. 147

2. The Bureau’s Proposal, In Effect, Requires That Accounts Receivable

Management Industry Retain All Call Recordings ........................................... 147

XV. COMMENTS ON §1006.104 – RELATION TO STATE LAWS ..................... 148

XVI. COMMENTS ON §1006.108 and PROPOSED APPENDIX A .................... 149

P a g e | 15

A. State Exemption from the FDCPA and the Bureau’s Proposal .................. 149

B. The Bureau Should Clarify that State Laws that Impose Additional or

Different Requirements Cannot Replace the FDCPA or Regulation F ............... 151

2. The Bureau’s Approach to State Exemption is Broader than that Plainly

Allowed by Section 817 and, therefore, may not be entitled to deference. ....... 152

3. Allowing Inconsistent State Laws to Replace the FDCPA and Regulation

F Is Not in Line with the FDCPA’s Purpose or the Bureau’s Rulemaking

Authority. ............................................................................................................ 153

CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................... 155

16 | P a g e

Chapter One- Overview and Studies

I. INTRODUCTION

Congress enacted the FDCPA in 1977 to protect consumers from abusive,

threatening, and unfair collection practices. At the time, abuses that needed to be

curbed included intimidation by individuals claiming to be part of the debt

collection profession, threats of imprisonment, publication of debtor lists in local

newspapers, repeated harassment, the placement of hundreds of telephone calls to

consumers (often at work or in the middle of the night), as well as blatant

misrepresentations to consumers regarding their debt and the creditor’s legal

recourses.

The most outrageous actions referenced above are extreme exceptions. In today’s

world with a severely outdated FDCPA, rarely does a case involve actual damages

or serious harm to a consumer. Egregious violations are increasingly rare, and ACA

has worked with the Bureau to identify bad actors and has applauded its

enforcement actions against them.

7

7

ACA International, CFPB Alleges Large Credit Repair Companies Violated Consumer Laws (May 2,

2019), available at https://www.acainternational.org/news/cfpb-alleges-large-credit-

repair-companies-violated-consumer-laws.

P a g e | 17

During the passage of the FDCPA in Congress, ACA was active in those discussions,

ultimately supporting it and testifying before Congress on the matter. Although the

legislative history of the FDCPA included a call for it to be revisited and

modernized as appropriate, the law has not been significantly updated or

modernized since that time more than 40 years ago. As a result, where regulatory

uncertainty exists within the statute, the judicial arm, charged with interpreting

and applying the FDCPA, has rendered a legal patchwork of federal and state case

law that is highly inconsistent among jurisdictions.

A. Significant Ambiguities in the FDCPA cause Unnecessary

Litigation.

In its discussion of the proposed rule, the Bureau recognizes that the nearly 12,000

annual plaintiff litigation filings under the FDCPA, as well as the threat of FDCPA

filings, imposes significant costs for the accounts receivable management industry

(84 FR at 23370). Most notably, given the mechanical language and requirements

under the FDCPA, self-described “consumer protection” attorneys have generated

unnecessary litigation based on technical, inconsequential, non-abusive violations.

8

Many consumer attorneys throughout the country coordinate with their clients to

call collectors with the intent of eliciting a response that will form the basis of an

FDCPA suit. These bait calls or trap calls are no different than acts of entrapment

that plague well-intended collectors.

These attorneys burden collection agencies (which as noted are often small

businesses)

9

with demands for tens of thousands of dollars to resolve claims arising

8

See, e.g., Anenkova, 201 F.Supp.3d at 636-39 (granting summary judgment against plaintiff who

sued a debt collector because a barcode was visible on the envelope); McShann v. v. Northland Grp.,

Inc., Case No. 15-00314-CV-W-GAF, 2015 WL 8097650 (W.D. Mo. Dec. 1, 2015) (granting a motion to

dismiss where a plaintiff sued because a demand letter with a “window” displayed the plaintiff’s

name, address, and account number); Simmons v. Med-I-Claims, No. 06-1155, 2007 WL 486879, at

*9 (C.D. Ill. Feb. 9, 2007) (granting summary judgment where plaintiff sued because the return

address listed in the envelope was listed for “Med-I-Claims” instead of “Med-I-Claims Services Inc.”);

Masuda v. Thomas Richards & Co., 759 F.Supp. 1456, 1466 (C.D. Ca. 1991) (rejecting plaintiff’s

argument that debt collector violated FDCPA by including in an envelope language like

“PERSONAL & CONFIDENTIAL” and “Forwarding and Address Correction Requested.”).

9

ACA, SMALL BUSINESS IN THE COLLECTIONS INDUSTRY IN 2019 (ACA International White Paper

April 2019), available at https://www.acainternational.org/assets/advocacy-resources/aca-wp-

smallbusiness-2019-002.pdf.

P a g e | 18

from hyper-technical violations of the law. Moreover, they and their clients openly

invoke the FDCPA as a pretext for avoiding the repayment of lawful debt. Some

attorneys even use the FDCPA to drive their bankruptcy law practices. Many go so

far as to search public court databases for newly filed collection actions to recruit

new clients. Most importantly, these attorneys thrive on the mere threat of

litigation, knowing that most agencies will pay $5,000 to settle a frivolous case

instead of spending $50,000 to successfully defend one.

Notably, the FDCPA does not require consumers to show that a debt collector’s

misconduct was intentional. See, e.g, Russell v. Equifax A.R.S., 74 F.3d 30, 33 (2d

Cir. 1996) (“Because the Act imposes strict liability, a consumer need not show

intentional conduct to be entitled to damages.”); Beuter v. Canyon State Prof ’l

Servs., Inc., 261 F. App’x 14, 15 (9th Cir. 2007) (holding that the FDCPA imposes

strict liability on debt collectors and that they “are liable for even unintentional

violations of the FDCPA”). Likewise, the FDCPA incentivizes consumers and their

attorneys to diligently monitor the accounts receivable management industry’s

behavior by allowing the recovery of “any actual damage,” statutory damages up to

$1,000, as well as the consumers’ attorney’s fees and costs. 15 U.S.C. § 1692k. The

CFPB should be studying the volume of legitimate v. non-legitimate lawsuits and

working with Congress to resolve whether this strict liability is appropriate.

ACA International impresses upon the Bureau that each proposed regulation must

be scrutinized with an eye toward whether it will invite new and creative theories

for plaintiffs’ attorneys to exploit.

Accordingly, ACA’s comments will not merely address the Bureau’s proposed rules

from a compliance and consumer protection standpoint, but with an eye toward

curtailing the dubious litigation that may ensue from their promulgation.

B. Courts have developed FDCPA “Policy” without the Benefit

of Regulatory Tools

Courts have created their own unintended consequences with their interpretations

of the FDCPA over the last 40 years of litigation. Judicial constructs like the least

P a g e | 19

sophisticated consumer are nowhere in the FDCPA text.

10

Likewise, courts made up

the doctrine of “overshadowing,” which is now being used to attack anything that

deviates from mechanical statutory language and that might be considered

“congenial.”

11

And, even when agencies utilize the FDCPA’s statutory language,

such as by including in their letters the validation notice language found in Section

1692g(a, they get penalized by courts. Indeed, courts have muddied the waters

about how to describe “in writing” dispute requirements in g notices (despite the fact

that the required language is spelled out in the FDCPA) and whether a collector

can encourage a telephone call to dispute or ask questions.

12

These and other

judicial rewrites to the FDCPA have effectively promulgated rules and regulations

with no notice, no opportunity to comment, and no coherent public policy to balance

the costs and benefits of the rulings.

ACA welcomes all clarity, safe harbors that allow collectors to use plain language,

and interpretations where ambiguity has created differences between courts and

circuits.

10

See Lait v. Medical Data Systems, Inc., No. 18-12255, 2018 WL 5881522, at *1-2 (11th Cir. Nov. 9,

2018) (noting the decisions of different courts on whether to apply the least sophisticated debtor

standard in different provisions of the FDCPA).

11

See, e.g., Gruber v. Creditors’ Prot. Servs., Inc., 742 F.3d 271 (7th Cir. 2014) (affirming dismissal of

the claim that the statement immediately preceding the § 1692g(a) disclosure that “[w]e believe you

want to pay your just debt” overshadowed and was otherwise inconsistent with the verification

disclosure because the statement does not contradict any of the required disclosure and instead is

merely “a congenial introduction to the verification notice and is best characterized as ‘puffing’.”)

12

Hooks v. Forman Holt Eliades & Ravin L.L.C., 717 F.3d 282 (2d Cir. 2013) (holding that a

verification notice violated the FDCPA by stating that the consumer must dispute the debt in

writing); Riggs v. Prober & Raphael, 681 F.3d 1097 (9th Cir. 2012) (stating that “[w]e have

previously held that a collection letter, called a ‘validation notice’ or ‘Dunning letter,’ violates §

1692g(a)(3) of the FDCPA ‘insofar as it state[s] that [the consumer’s] disputes must be made in

writing.’”) compared to Caprio v. Healthcare Revenue Recovery Group, L.L.C., 709 F.3d 142 (3d Cir.

2013) (letter containing the § 1692g verification notice was deceptive in that it urged the consumer to

telephone the debt collector if the consumer felt he did not owe the amount claimed by the collector,

when telephoning would not entitle the consumer to the verification of the debt if the consumer

disputed the debt in writing. “More is required than the mere inclusion of the statutory debt

validation notice in the debt collection letter—the required notice must also be conveyed effectively

to the debtor. . . . More importantly for present purposes, the notice must not be overshadowed or

contradicted by accompanying messages from the debt collector.”)

P a g e | 20

Where the Bureau has added new and additional regulatory requirements, however,

ACA challenges the factual assumptions, rationale, and cost-benefit studies (or lack

thereof) that underlie the proposals.

C. Regulatory Overreach in Regulation F Particularly Harms

Small Businesses

Finally, ACA International urges the

Bureau to be mindful of the

cumulative effect of these proposed

regulations. Viewed in isolation, a

single proposed rule may seem

reasonable and suggested with the

best of intentions. However, there is a

collective “speed bump” effect to these

proposed regulations when taken

together. ACA International

maintains that there are already

plenty of speed bumps on the debt

collection road and plenty of

protections for consumers. More speed bumps and overly complex compliance

burdens will harm small businesses. These impossible speed bumps will also

decrease meaningful consumer communication, which will drive creditors to

litigation and ultimately harm the ability of consumers to access credit and services.

1. Small Business Recommendations went Unaddressed

Despite some significant improvements to its original outline, the CFPB’s proposal

continues to ignore some critical feedback provided from Small Entity

Representatives (“SERs”) during the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement

Fairness Act (“SBREFA”) process. This is particularly worrisome, as the majority of

the accounts receivable management industry is comprised of small businesses.

One prime example that SBREFA comments were ignored is the itemization

requirement in the model validation form at § 1006.34(c). Small business creditors

were not invited to be part of the SBREFA process; but the Bureau’s proposal

assumes that such creditors will be able to provide additional documentation and

P a g e | 21

information for itemization in the model validation notice despite the proposal

ostensibly not sweeping in first parties.

13

As we outline extensively later in the

comment, this ultimately harms both the accounts receivable management industry

and small business creditors, who will not be able to easily comply with these

proposed requirements. As noted throughout our comments, it is particularly

problematic for small businesses collecting medical debt.

We disagree with the Bureau’s decision to not provide a substantive analysis as

described in footnote 58, where it states that creditors are not affected by the

proposal:

Certain proposals under consideration in the Small

Business Review Panel Outline and discussed in the

Small Business Review Panel Report are not included in

this proposed rule and are not discussed in part V. For

example, because this proposed rule would apply only to

FDCPA-covered debt collectors, the Bureau does not

include a discussion of proposals under consideration that

would have imposed information transfer requirements on

first-party creditors who generally are not FDCPA-

covered debt collectors.

The new itemization requirement clearly imposes extra burdens on all creditors (not

just those that collect their own debt). Nevertheless, the Bureau conducted no

analysis of how the new itemization requirements would impact the small

businesses who depend upon the accounts receivable management industry to

ensure their customers pay the creditors’ bills.

Another example of feedback ignored in the SBREFA process includes requiring

differentiation between work and personal emails.

14

Footnote 361 of the proposal

notes that SBREFA comments, “were similar to ANPRM comments submitted by

several industry members, who noted that debt collectors may not be able to

determine accurately whether an email address is provided by an employer because,

among other things, the domain name may not signify that it is a work email or the

13

See, ACA SBREFA Panel Rep. at 18.

14

See NPRM at 187-189.

P a g e | 22

consumer may consolidate multiple email accounts.” As outlined in greater detail in

our specific comments on this matter,

15

there is still not a vendor that can easily

make this differentiation between work and personal emails. Thus, it would make it

unduly burdensome for smaller members of the industry to be able to use email in a

way that they can guarantee compliance with the proposed requirements for work

emails.

This is particularly problematic since the Bureau acknowledges in its proposal that

collection agencies who use email may have a competitive advantage:

Debt collectors who use electronic communication may

also benefit to the extent that some consumers are more

likely to engage with debt collectors electronically than by

telephone call or letter. During the SBREFA process,

several small entity representatives said that

communication by email or text message was preferred by

some consumers and would be a more effective way to

engage with them about their debts.”

16

It seems that the Bureau is acknowledging that there is a competitive advantage for

agencies that can use email, who mostly are the largest at this point. Despite this

recognition, the Bureau is ignoring critical SBREFA feedback about the limitations

of smaller agencies to be able to differentiate between work and personal emails.

In other CFPB proposals such as the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act rule, the

Bureau acknowledged that smaller entities would need to rely on vendors to come

into compliance with complex new regulations, and has since requested more

information from financial services providers about some of the burdens financial

service providers are facing.

17

This is comparable to having a new system in place to

differentiate work and personal emails, and should serve as a lesson learned about

weighing the cost versus benefits of overly complicated new requirements. During

discussions about HMDA, previously, the Small Business Administration Office of

15

See, infra Ch. 2, Section II.F.

16

NPRM at 412.

17

Home Mortgage Disclosure (Regulation C), 84 Fed. Reg. 20972 (proposed May 13, 2019) (to be

codified at 12 C.F.R. pt. 1003).

P a g e | 23

Advocacy found creating new computer systems to be unduly burdensome for small

businesses.

18

In its letter to the Bureau on this, SBA Office of Advocacy stated:

At Advocacy’s roundtables, the participants stated that it

will be costly to develop a computer system to collect the

information that is required. According to the

participants, it will be far more costly than the Home

Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) rulemaking. In HMDA,

small entities added to an existing system. To comply

with the requirements of section 1071, small entities will

need to build an entirely new system. Advocacy believes

that the implementation of section 1071 of the Dodd-

Frank Act will be costly for small financial institutions.

Similarly, having a compliance system in place that can ensure that all emails are

not used as work emails would be extremely burdensome, require extensive training

(and yet to be created software), and arguably may still even be impossible since

there is no way to read a consumer’s mind in how they are using a particular email

address.

II. COMMENTS ON CONSUMER FOCUS GROUP

STUDIES

A. Consumer Impressions don’t Equate to Violations.

The Bureau’s Fors Marsh Cognitive Interview research confirms that consumer

perception of debt collection as “threatening”

19

is often because collection agencies

feel they must use the formal statutory language required under the FDCPA to

avoid plaintiffs’ lawsuits. In truth, collectors themselves are relatable. Over 70

18

See, e.g., Office of Advocacy Comment on the CFPB’s Request for Information Regarding the Small

Business Lending Market (Sep. 14, 2017), available at https://www.sba.gov/advocacy/9-14-2017-

advocacy-submits-comments-cfpbs-request-information-regarding-small-business.

19

FORS MARSH GRP., Debt Collection Validation Notice Research: Summary of Focus Groups,

Cognitive Interviews, and User Experience Testing (February 2016), at 8, available at

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_debt-collection_fmg-summary-report.pdf.

P a g e | 24

percent of debt collection professionals are women; racial and ethnic minority

groups account for 40 percent of the total collections workforce.

20

Industry

employees spend more than 520,000 hours per year in volunteer activities.

21

Bureau

efforts that allow collectors to empathize early and engage in problem solving with

consumers should benefit both consumers and industry.

22

Overall, however, ACA is skeptical about the reliability of the Fors Marsh studies

for any purpose other than copy-testing. Focus groups are not the best method to

test nationwide experience with debt collection, in general.

23

And to the extent the

CFPB is relying on the focus groups to identify problematic collection issues, “focus

groups are not useful when the researcher needs to assess the magnitude of a

problem.”

24

Further, this study, in particular, has serious deficits that make it wholly

unreliable. The Fors Marsh study makes no effort to justify or explain the number

of focus groups or their composition.

25

For instance, the study does not describe the

20

Diversity in the Collections Industry: An Overview of the Collections Workforce, at 2 (January

2016), available at https://www.acainternational.org/assets/research-statistics/aca-wp-diversity.pdf.

21

ACA International Fact Sheet (January 2019), available at

https://www.acainternational.org/assets/advocacy-resources/aca-fact-sheet.pdf.

22

ACA therefore supports proposed provision § 1006.34(d)(3)(i).

23

See, e.g., R.A. Krueger & M.A. Casey, Participants in a Focus Group. Focus Groups: A practical

guide for applied research (5th ed. 2014), https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-

binaries/24056_Chapter4.pdf (“Keep in mind that the intent of focus groups is not to infer but to

understand, not to generalize but to determine the range, and not to make statements about the

population but to provide insights about how people in the groups perceive a situation.”); Martha

Ann Carey, International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences 277 (2d ed. 2015) (“A

major concern for data quality is the potential for a ‘group think,’ the phenomenon of participants

being carried along by the group interaction and agreeing with the overall discussion.”); David

Morgan, Qualitative Research Methods: Focus groups as qualitative research 12 (1997) (“Once

participants sense that there is a distinct agenda for the discussion and that the moderator is there

to enforce that agenda, then they are likely to acquiesce in all but the most extreme circumstances.”).

24

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, supra note 24 at 274. Krueger RA.

Focus groups. A practical guide for applied research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications,

Inc; 1994.

25

Benedicte Carlsen & Claire Glenton, What about N? A methodological study of sample-size

reporting in focus group studies, BMC Medical Research Methodolog, at 2 (2011),

P a g e | 25

efforts to recruit or select participants, does not justify the location of the focus

groups, does not describe the participants’ socioeconomic backgrounds, and

generally does not describe why the researchers chose to format the groups in the

way they did.

26

The study also does not describe whether the researchers believed

the composition of the focus groups was sufficient to reach the “point of saturation.”

“Saturation” is critical for ensuring that the depth and breadth of the participants’

responses adequately capture perceptions on debt collection.

27

Instead, ACA presents an alternative study based on measurable historical facts

from a sample of millions. This study concludes that legitimate disputes about debt

collection comprise less than ½ percent of all collected consumer accounts.

1. The Fors Marsh Study lacks a Robust Sample Set and Data Clarity

While the CFPB touts its consumer experience survey data as the “first

comprehensive and nationally representative data,”

28

its overall sample of

individuals with experience with the accounts receivable management industry is

remarkably small. Of the 2,132 survey respondents, only 682 individuals (32%)

report being contacted by the accounts receivable management industry. Despite

this, the CFPB continually couches its findings in relation to all American

consumers with debt collection experience.

29

https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-11-26 (“[T]he number of

focus groups depends on the complexity of the research question and the composition of the groups.”)

26

What about N?, supra note 26, at 8 (“[R]esearchers should always provide correct and detailed

information about the methods used[.]”); Focus Groups as Qualitative Research, supra note 24, at 12

(“[I]nadequate recruitment efforts are the single most common source of problems in focus group

research projects.”).

27

What about N?, supra note 26, at 5-7.

28

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU, Consumer Experiences with Debt Collection: Findings

From the CFPB’s Survey on Consumer Views on Debt, Jan. 12, 2017, [hereinafter Consumer

Experiences] available at https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-

reports/consumer-experiences-debt-collection-findings-cfpbs-survey-consumer-views-debt/

29

See, ACA, AN OVERVIEW OF THE ANALYTICAL FLAWS AND METHODOLOGICAL SHORTCOMINGS OF THE

CFPB’S SURVEY OF CONSUMER EXPERIENCES WITH DEBT COLLECTION, 2, 6 (ACA International White

Paper February 2017), [hereinafter ACA] available at

https://www.acainternational.org/assets/research-statistics/wp-cfpbsurvey.pdf.

P a g e | 26

Rather than report its findings with any degree of statistical certainty, the CFPB

describes the survey report as a “descriptive” exercise to “highlight patterns that

may be of policy interest” and “to sketch, from consumers’ perspectives, the broad

experience of debt collection.” The CFPB further cautions that this descriptive

sketch “does not present standard errors or statements about the statistical

significance of the differences” across groups.

30

The presentation of data lacks clarity and lends itself to overestimating the

prevalence of certain findings. By focusing almost entirely on percentages

throughout the report, coupled with a near-total absence of raw numbers or sample

sizes for individual questions, the CFPB offers only limited context for interpreting

responses or situating them within the larger sample. For example, the CFPB

reports that “three in-four consumers report that debt collectors did not honor a

request to cease contact.” A more accurate description of this finding would note

that 75% of consumers who reported continued contact after a request to cease

communication are a subset of the 42% who requested contact to cease; this 42% is

itself a subset of the 32% of the total sample that have been contacted about a debt

in collection. Thus, the “three-in-four consumers” actually represents roughly 215 of

the 2,132 consumers surveyed, or only 10% overall.

Furthermore, the report addresses consumers who ask debt collectors to stop

contact. Despite the FDCPA requiring consumers to submit a request to stop

contact in writing, the CFPB reported findings for the 87% of respondents who “said

they made the request by phone or in person only.” Thus, about 28 people of a 2,132

person sample of consumers with debts on their credit histories reported having

submitted a cease and desist request in the form required by the FDCPA yet still

had contacts continue.

31

This is 1.3 percent. Even 1.3 percent is likely overestimated

when one considers the impact of priming and memory on self-reported surveys.

2. Consumer Survey Evidence is Unreliable

Decades of consumer learning and memory research demonstrates that consumer

memory and self-reported experience is inherently unreliable. As multiple

researchers have concluded, consumer recall of past experience is subject to

30

Id. at 2 (citing Consumer Experiences, supra note 13).

31

ACA, supra note 30, at 2.

P a g e | 27

distortion and can be guided by marketing communications, researcher feedback,

and priming:

Learning from self-generated experience with a product or

service is not a simple process of discovering objective

truth. It is, to a greater extent, open to influence, and the

consumer’s confidence in the objectivity of such learning

can be illusory.

32

The multiple instances where the CFPB found that consumers misinterpreted or

were confused by the survey questions suggests that the survey itself might be a

flawed instrument, a point that ACA International stressed to the CFPB before the

survey was approved and sent to consumers.

33

Specifically, footnote 24 states that

“the survey did not specifically define disputes” and that “consumers’ perspectives

on whether they had disputed a debt may differ from the definition of dispute used

by a given creditor or collector or what may constitute disputes pursuant to the

FCRA and FDCPA.” It is quite problematic that a survey purporting to evaluate

consumer experiences with the accounts receivable management industry fails to

present questions that accurately represent the terms by which that industry is

regulated.

The report also found the consumers with more than one debt in collection were

more likely to be contacted multiple times per week. The CFPB found that these

same consumers were also more likely to report that they felt they were being

contacted too often, yet also observed that a “consumer who is contacted about

multiple debts is likely to experience a higher overall frequency of calls, and this

may make the consumer more likely to perceive any number of calls from any one

collector as ‘too often.’” Perhaps in the future the CFPB, and readers of its report,

would be better served by Bureau efforts to disentangle the relationship between

the number of debts in collection relative to the number of calls received by a

consumer.

32

Hoch, Stephen J. and John Deighton, Managing What Consumers Learn from Experience, JOURNAL

OF MARKETING, 53 (April 1989), quoted by Braun, Kathryn, Postexperience Advertising Effects on

Consumer Memory, JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH 25 (March 1999).

33

ACA, supra note 30, at 4, 27, 36, fns.32 & 34 (discussing key “caveats” that recognize that some

questions might have confused consumers).

P a g e | 28

3. Legitimate Disputes Comprise Less than ½ Percent of All Accounts

The Fors Marsh study relies on the memories of persons contacted by the accounts

receivable management industry to assess facts that ACA members can readily

track in their files. In fact, ACA conducted a macro analysis of its members’ dispute

data and determined that only 0.15% of disputed accounts have a basis in fact.

These legitimate disputes comprise less than 4.5% of all disputes submitted. And of

those legitimate disputes, 69% were valid because the borrower paid the debt in full

prior to the collection agency making its initial contact. This is a time-lag problem,

not a compliance issue.

“Legitimate” Disputes

Total

Accts.

Total

Disputes

Duplicative

Dispute

Validated Acct. or

Duplicative

Dispute

Error/No

media

Acct.

Paid in

Full

TOTAL

Total 2,263,845. 77,124 15,463 74,487 1,049 2,343 3,392

OF Total Disputes 3.41% 20.05% 96.58% 1.36% 3.04% 4.40%

OF Total Accts. . 3.41% 0.683% 99.850% 0.046% 0.103% 0.150%

Of "Legit.” Disputes 30.9% 69.1% 100.0%

* Duplicative disputes are defined somewhat consistent with NPRM §1006.38(a)(1)

as: a dispute submitted by the consumer in writing that is substantially the same as

a dispute previously submitted by the consumer in writing for which debt collectors

already has satisfied the requirements of paragraph (d)(2)(i). Many collection

agencies record and respond to disputes outside the validation period for customer

service purposes.

P a g e | 29

Conclusion

In fact, from a 2018 and 2019 sample set of over 2.2 million accounts, ACA

determined that the data supporting collections on those accounts is accurate over

99.85 percent of the time.

This study provides three key takeaways:

• The numbers cited in the Fors-Marsh study that indicate

malfeasance by accounts receivable management industry are

dramatically inflated when compared to actual data.

• Concerns about consumers not exercising their right to dispute

debts are unfounded, as invalid accounts are very rare.

• Duplicate disputes comprise over 20 percent of all disputes.

B. Calling Data Research

The research referencing “calling data”

34

does not provide the public and

researchers enough source material for adequate inspection and analysis. Specific

failures with respect to the research provided include:

• No clear reference or citation for the data set used

• No sample size is provided

• No methodology is described

• No algorithms are provided for the simulation research

• No assumptions are provided, nor the rationale behind the assumptions

Therefore, it is not possible to contextualize the results of the simulations or to

understand the real-world data they are based on.

The NPRM expands upon the details of the “calling data” findings for nearly ten

pages,

35

outlining their justification for proposed call caps. However, within those

ten pages there is almost a total absence of data and technical detail necessary to

34

See NPRM at 370.

35

NPRM at 370 – 379

P a g e | 30

support their claims. As the rationale for call caps derives almost entirely on the

simulation research and data from one collection agency, there should be clear

documentation of the research, sample, methodology, and easy access to a final

report.

The Bureau should not be given credit for providing the public the opportunity to

comment upon the “calling data” study, and the call-caps rule that is based on the

study, in light of this deficit in transparency.

III. DATA FROM STATE REGULATION ADVISES

EXTREME RULEMAKING CAUTION

The Bureau must carefully balance new collections requirements with market

incentives. For creditors, the alternative to debt collection is litigation. For many

reasons, consumers who have breached credit contracts are much better off

communicating privately with debt collectors than being sued by creditors in state

or local courts:

• Consumers must often pay attorneys’ fees and costs of collections litigations,

• Consumers may lose chances to settle debt for less than face value, and

• When a lawsuit is filed in state or county court, the lawsuit filing, and

defaulted debt becomes a matter of public record with all the attendant

reputational harm.

Too much regulatory burden or frivolous plaintiffs’ class action risk, however,

negates the advantages of debt collection and will drive more creditors to elect

litigation sooner or more frequently, particularly for certain riskier classes of debt.

Creditors prefer out-of-court resolution through debt collection because it usually is

faster, predictable, is private, avoids attorney fees, and typically maintains the

goodwill of the consumer. But where regulatory hurdles increase capital costs, on-

going burdens, or regulatory risk, creditors and collection agencies may choose to

file collections actions where notice pleading rules and medical information privacy

rules are clear and a 100 percent recovery is more likely.

P a g e | 31

A. The 2015 New York DFS Debt Collection Rules Increased

Collection Litigation by 93%

Following the enactment of new debt collection regulations in 2015, in New York

State, collections lawsuit filings rose 32% in 2018 and 61% in 2017 from pre-2015

levels.

36

ACA believes that this is an overall bad outcome for consumers, and

advises the Bureau to avoid tipping the trend toward litigation at a national level.

The New York Department of Financial Services issued regulations that took effect

on March 3, 2015, except for certain provisions relating to itemization of the debt to

be provided in initial disclosures and relating to substantiation of consumer debts,

which were effective Aug. 3, 2015. The New York DFS rules are similar in many

respects to those proposed by the Bureau.

1. Itemization on Validation Notices

The DFS' regulations require that the validation notice or “g notice” contain a

written notification that includes: (1) disclosure that debt collectors are prohibited

from engaging in abusive, deceptive and unfair debt collection; (2) notice of the

types of income that may not be taken to satisfy a debt; and (3) itemization similar

to that proposed by the Bureau, i.e. detailed account-level information, including

the name of the original creditor and an itemization of the amount of the debt. That

itemization must include the debt due as of charge-off, total amount of interest

accrued since charge-off, total amount of noninterest fees or charges accrued since

charge-off and total amount of payments made since charge-off.

37

2. Disclosures About Debts for Which the Statutes of Limitations May be Expired

The DFS rules also require certain disclosures about statutes of limitations if the

debt collector “knows or has reason to know” that the statute of limitations has

expired. This section also mandates that collection firms maintain “reasonable

procedures” for determining whether the statute of limitations has expired.

36

Yuka Hayashi, Debt collectors wage comeback, WALL STREET JOURNAL, July 5, 2019 (crediting New

Economy Project, a consumer advocacy group).

37

23 NYCRR § 1.2(b)(2).

P a g e | 32

3. Increased Substantiation of Consumer Debts

If a consumer disputes a debt, collection firms may treat the dispute as a request for

substantiation or must provide instructions as to how to make a written request for

substantiation of the debt. Collection firms must provide substantiation within 60

days of receiving a consumer’s request and must cease collection efforts during that

time.

DFS defined documentation required for substantiation as including either a copy of

a judgment against the consumer or: (1) the signed contract or some other document

provided to the alleged consumer while the account was active demonstrating that

the debt was incurred by the consumer; (2) the charge-off account statement (or

equivalent document) issued by the original creditor; (3) a description of the

complete chain of title, including the date of each assignment, sale and transfer;

and (4) records reflecting any prior settlement agreement reached under the

regulations. Collection firms must retain all evidence of the request, including all

documents provided in response, until the debt is discharged, sold or transferred.

38

4. Debt Payment Procedures

If an agreement to a debt payment schedule or settlement is reached, the collection

firm must provide written confirmation of the agreement and notice of exempt

income. The collection firm must also provide a quarterly accounting statement

while the consumer is making scheduled payments.

5. Communication through Email Restricted

After mailing the initial required disclosures, debt collectors may communicate with

a consumer through email upon receipt of consumer consent, provided the email

account is not owned or provided by the consumer’s employer.

38

23 NYCRR § 1.4

P a g e | 33

B. Over-Regulation of Communications Drives Creditors to

Litigation

In New York City courts, account collection filings in year 2017 rose 61% from 2016

levels. In 2018, account collection filings rose another 32% from 2017 levels.

39

Prior

to the New York DFS rules, lawsuit filings to collect debts had declined for nearly a

decade due to tougher court requirements imposed on collectors.

40

ACA members explain the reasons for this:

• Creditors did not want to invest the money to update systems in order to