Goal-Setting in the Career Management Process: An Identity

Theory Perspective

Lindsey M. Greco

Oklahoma State University

Maria L. Kraimer

University of Iowa

A common and important feature within models of career management is the career goal, yet relatively

little is known about the factors influencing career goals and when and how career goal setting occurs.

Drawing from Ashforth’s (2001) model of role transitions we propose and test a model wherein

mentoring experiences of early career professionals relate to short- and long-term career goals through

professional identification. Using survey data collected at three points in time from 312 early career

professionals, we find that psychosocial mentoring, but not career mentoring, positively relates to

professional identification. For short-term goal outcomes, professional identification positively relates to

extrinsic goals, intrinsic goals, and goals that are high quality (i.e., specific, difficult, to which one is

committed). For long-term goal outcomes, professional identification positively relates to extrinsic and

intrinsic goals, but not to goal quality. Instead, in the long-term goal model, psychosocial mentoring is

directly related to goal quality. The theoretical and practical implications of this study for professional

identification, career goals, and how mentors can facilitate career goals are discussed.

Keywords: careers, goal-setting, mentoring, professional identification

Supplemental materials: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/apl0000424.supp

Employees are more actively involved in and responsible for the

management of their careers now than they have been in the past.

According to the boundaryless and protean careers perspectives,

the responsibility for charting and navigating one’s career is placed

firmly in the hands of the individual as opposed to his or her

employing organization (e.g., Arthur & Rousseau, 1996; Eby,

Butts, & Lockwood, 2003). Individual career planning and man-

agement processes are outlined in various career management

models including the widely cited frameworks of Greenhaus

(1987); London (1983), and Gould (1979). A common and impor-

tant feature within each model is the career goal, defined as any

desired career outcome, such as promotion, salary increase, or skill

acquisition which individuals wish to attain (Greenhaus, 1987;

Seibert, Kraimer, Holtom, & Pierotti, 2013). Specifically, in

Greenhaus’s (1987) model of career management, goal setting

facilitates the development and implementation of a career strat-

egy, which produces progress toward stated goals. In London’s

(1983) theory of career motivation, career insight is defined as the

clarity of an individual’s career goals, and setting and trying to

accomplish career goals is part of career motivation. Finally,

Gould’s (1979) model of career planning suggests that planning

career goals leads to enactment and attainment of career goals.

However, as Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk (2010) note

“although many writers on career management discuss the virtues

of goal setting, there is little research in the area of career goals”

(p. 54). That is, within the various career management models and

related research, most work begins with the assumption individuals

already have career goals—the literature then focuses on career

strategies to achieve said goals. In the few studies that have

examined individual or personal career goals, they are positioned

as antecedents of work attitudes such as job satisfaction and

well-being (e.g., Brunstein, 1993; Brunstein, Schultheiss, & Gräss-

mann, 1998; Maier & Brunstein, 2001; Roberson, 1989, 1990), or

career goals are addressed in a tangential fashion (e.g., assessing

distance from career goals, goal importance, goal progress; Abele

& Spurk, 2009; Dik, Sargent, & Steger, 2008; Maier & Brunstein,

2001; Noe, 1996; Noe, Noe, & Bachhuber, 1990). Overall, re-

search and theory have not addressed factors influencing the

creation of career goals and when and how career goal setting

occurs (Seo, Barrett, & Bartunek, 2004).

It is important to understand the factors that influence career

goals for three main reasons. First, in the era of the boundaryless

or protean careers, employees cannot count on organizationally

imposed career goals to manage their careers, so understanding

factors that influence goal setting and the content of career goals

This article was published Online First June 6, 2019.

Lindsey M. Greco, Department of Management, Spears School of Busi-

ness, Oklahoma State University; Maria L. Kraimer, Department of Man-

agement and Organizations, Tippie College of Business, University of

Iowa.

Maria L. Kraimer is now at the School of Management and Labor

Relations at Rutgers University.

This article was presented at the 2018 Academy of Management Annual

Meeting. We thank Scott Seibert, Ernest O’Boyle, and Eean Crawford for

their helpful comments on an early version of this article.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Lindsey

M. Greco, Department of Management, Spears School of Business, Okla-

homa State University, 229 Business Building, Stillwater, OK 74078.

E-mail: [email protected]

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Journal of Applied Psychology

© 2019 American Psychological Association 2020, Vol. 105, No. 1, 40–57

0021-9010/20/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/apl0000424

40

can provide insight into themes within this new career manage-

ment process. In particular, understanding the content of career

goals offers a unique lens into how individuals conceptualize their

future work selves (e.g., Markus, 1983; Markus & Nurius, 1986)

and subsequently manage their careers. Second, because career

management models assume that career goals, like other work

goals, will direct an individual’s attention, time, and energy, career

goals provide a crucial organizing standard that guide career-

related decisions by motivating or limiting choices about how to

achieve desired career outcomes (King, 2004). For example, goals

can determine an employee’s search for feedback and information

seeking as different types of goals change the kind of information

in the environment that the individual perceives and attends to

(Ashford & Cummings, 1983). Therefore, understanding the cre-

ation and content of career goals can provide important informa-

tion for those early in their careers in establishing a career trajec-

tory. Third, goals and goal attainment are important characteristics

in theories of job-related attitudes; goals are expected to positively

relate to job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organi-

zational identification to the extent that the job promotes the

attainment of valued goals (Allen & Meyer, 1997; Ashforth &

Mael, 1989; Locke, 1976; Mael & Ashforth, 1992). Thus, infor-

mation about the formation and content of individual goals can be

valuable in managing job-related affect. In sum, without knowing

the factors that may influence an individual’s career goals, our

understanding of the outcomes of those goals on the career man-

agement process is incomplete.

The present study uses an identity theory lens to examine the

creation of personal, career related goals in early career pro-

fessionals. Based on self-verification theory and Ashforth’s

(2001) model of role transitions (reviewed below), we examine

a mediated model in which mentoring experiences relate to

different types of career goals, through professional identifica-

tion. Based on the findings from a qualitative pilot study, we

examine career goals in terms of goal content, either intrinsic or

extrinsic, and goal quality, the extent to which one’s goal is

difficult and specific and one is committed to it. We test the

mediated model using a sample of graduate students preparing

for professional careers.

This study contributes to the literature on identity formation and

career management by examining the development of professional

identification and career goals during the role transition process.

Understanding how identification relates to the career goals early

career professionals set for themselves can be used as a basis for

understanding career aspirations and trajectories for professional

workers. This study also contributes to goal setting theory by

examining the content and characteristics of goals in the career

context. Career goal setting is often done absent formal goal

setting mechanisms, and this context has received sparse attention

in the both goal setting and careers literatures. We expand this

research by assessing both the content and quality of personal

career goals. A final contribution of the study is to the mentoring

and developmental relationships literature. Responding to calls to

explicitly define when and why mentoring is associated with

particular facets of socialization (Allen, Eby, Chao, & Bauer,

2017), we recognize that career mentoring is similar to serial

tactics and psychosocial mentoring is similar to investiture tactics.

We also identify a possible explanation, specific content and

quality of career goals, for why mentoring positively relates to

protégée career outcomes.

An Identity Theory Perspective of Career Goals

From the perspective of boundaryless (e.g., Arthur & Rousseau,

1996) and protean (e.g., Mirvis & Hall, 1996) careers, employees,

rather than the organization, are responsible for charting their own

career trajectories. However, the possible trajectories for individ-

uals’ careers are practically unlimited, with no single template

setting the standard for a particular career path. In place of an

organization providing some type of structure for career advance-

ment, workers, instead, may rely on identification with career-

related groups to help define and create career goals within the

career management process. Identification with a relevant group

can replace institutionalized career structures and provide a com-

pass for an individual beyond the walls of an employing organi-

zation (Fugate, Kinicki, & Ashforth, 2004).

One theoretical perspective that is particularly relevant to un-

derstanding how professionals develop career goals is Ashforth’s

(2001) model of role transitions and related identification process.

Ashforth’s (2001) model incorporates ideas from both social iden-

tification theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and identity theory

(Stryker & Serpe, 1994). Based on identity theory, he defines role

identities as socially constructed definitions of who a role occupant

is; such role identities have the purpose of anchoring self-

conceptions in social domains. Drawing from social identification

theory, Ashforth (2001) then defines role identification as a spe-

cific form of social identification which occurs if and when an

individual comes to define him/herself in terms of the role identity.

The higher the level of role identification, the more likely that one

will internalize the role identity as a partial definition of self, and

the more likely one will be to faithfully enact that identity (Ash-

forth, 2001). Both of these identity processes are relevant to goal

setting because enacting the role identity can be done by partici-

pating in behavior that “reflects a meld of institutionalized expec-

tations and idiosyncratic refinements” (Ashforth, 2001; p. 222).

One way to enact an identity, then, is to set personal goals that are

informed by and consistent with others in the referent group.

In the current study, we examine the role of mentors from the

referent group (i.e., the profession) and identification with that

group (i.e., professional identification) to career goal-setting

among early career professionals. Professional identification refers

to the extent that a professional employee experiences a perceived

oneness or bond with his or her profession (Hekman, Bigley,

Steensma, & Hereford, 2009a). Professional workers, such as

nurses, doctors, lawyers, and academics, are an ideal population to

study because they are defined less by where they work and more

by what they do (Pratt, Rockmann, & Kaufmann, 2006). The

career goals of professionals tend to be based on personal expec-

tations and examination of what is of fundamental import in one’s

life, such as professional norms and values, rather than organiza-

tionally assigned initiatives (Seo et al., 2004). Further, Cantor and

Zirkel (1990) stated that individuals devote considerable energy to

the creation of meaningful goals mostly during transitional stages

of life. For professionals, graduate school is a key transitional

stage into professional life because it provides systematic training

and socialization into that role (Austin & McDaniels, 2006; Baker

& Pifer, 2011; Howskins & Ewens, 1999; Price, 2009). This

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

41

MENTORING, IDENTIFICATION, AND CAREER GOALS

presents a unique application of Ashforth’s (2001) model of role

transitions as it relates to professional identification and career

goal setting as the first stage of the career management process.

In Ashforth’s (2001) model of role transitions, he expands on

the importance of transitional phases in goal setting by describing

the transition process as the assimilation of professional goals and

individual goals. During this transitional stage, mentors are likely

to play a key role in the development of professional identification

and possible career goals. This is because receipt of mentoring

may help newcomers satisfy two key psychological motives. Spe-

cifically, Ashforth (2001) proposes that role entry arouses psycho-

logical motives, including the need for control and the need for

belonging, which a newcomer will seek to fulfill in the context of

the role. The need for control is defined as a need to “master and

to exercise influence over subjectively important domains” (Ash-

forth, 2001, p. 67) and is associated with behaviors such as

information seeking, feedback seeking, proactive behavior, and

self-management. The need for belonging is the desire for attach-

ment with others or a sense of belonging with a larger group and

leads members to assume they share certain goals, values, and

commitment to the collective.

1

According to Ashforth (2001), the

more that those two motives are met, the more likely a newcomer

is to internalize the role, and the greater the identification with the

role. In turn, identification leads the newcomer to faithfully enact

the role identity, which results, in the current model, in establish-

ing identity related goals. We test these core propositions from

Ashforth’s (2001) role transitions theory by testing a model in

which career and psychosocial mentoring are hypothesized to be

positively related to professional identification, which, in turn is

related to the content (extrinsic and intrinsic) and quality (goal

difficulty, specificity, and commitment) of personal career goals

among graduate school students (see Figure 1).

Mentoring and Professional Identification

Mentoring has a variety of different connotations, sometimes

referring to dyadic relationships, or the “classic” mentor relation-

ship between senior (mentor) and junior (protégé) colleagues (e.g.,

Chao, Walz, & Gardner, 1992; Mitchell, Eby, & Ragins, 2015),

and at other times referring to a web of developmental work

relationships including informal mentors, role models, and coaches

(e.g., Kram, 1988; Kram & Isabella, 1985). In the current study,

we allow for multiple mentors, thus, our definition of mentoring is

consistent with the broader web of developmental relationships,

which Kram (1988) describes as “the range of possible adult

working relationships that can provide developmental functions

for career development” (p. 4). It has long been recognized that

organizational insiders, or mentors, are an important aspect of the

newcomer socialization process (e.g., Austin, 2002; Bauer &

Green, 1998; Ellis, Nifadkar, Bauer, & Erdogan, 2017; Humberd

& Rouse, 2016). Socialization dynamics include multiple pro-

cesses that define how individuals learn the social knowledge and

skills necessary to assume a particular role such as orientation,

training, apprenticeship programs, mentoring, and general on-the-

job learning (Van Maanen, 1978; Van Maanen & Schein, 1979).

Van Maanen and Schein (1979) argue that organizations imple-

ment a variety of bipoloar tactics to integrate new employees. We

specifically integrate the two tactics of serial and investiture so-

cialization into our discussion of mentoring because they concern

the social or interpersonal aspects of the socialization process

(Jones, 1986) and thus are most relevant to the role of mentors.

Below we explain how serial socialization relates to Ashforth’s

(2001) motive for control while investiture socialization relates to

Ashforth’s (2001) motive for belonging.

First, the serial (vs. disjunctive) tactic involves learning the new

job from a role model such as a mentor, supervisor, or more

experienced peer (vs. having no prior role incumbents to learn

from). Serial modes of socialization provide newcomers with

built-in guidelines to organize and make sense of their organiza-

tional situation (Van Maanen, 1978). As such, the serial tactic

corresponds to Ashforth’s (2001) motive for control for new role

entrants in that serial socialization by mentors helps early career

professionals master and exercise influence over their new roles.

Second, the investiture (vs. divestiture) tactic is the degree to

which newcomers receive positive (vs. negative) social support

from experienced members. Positive support affirms a newcomer’s

identity, capabilities, and attributes and results in more concrete

role orientations (Van Maanen & Schein, 1979) and perceptions of

fit (e.g., Cable & Parsons, 2001). This socialization tactic corre-

sponds to Ashforth’s (2001) motive for belonging in that investi-

ture socialization by mentors provides positive social support,

friendship, and opportunities to build significant interpersonal

relationships in their new roles. In sum, through serial and inves-

titure tactics, experienced members of the profession (i.e., men-

tors) may facilitate early career professionals’ adjustment by giv-

ing the newcomers needed advice and instructing them in how to

do their new jobs and by making them feel like they belong in the

profession (Allen, Eby, Poteet, Lentz, & Lima, 2004; Ashforth &

Saks, 1996; Ostroff & Kozlowski, 1992).

Relatedly, Kram (1985) outlined two primary mentor functions

provided by developmental relationships—career development

support and psychosocial support—both of which can contribute

to an individual’s growth and advancement (Kram, 1988). Both

career and psychosocial mentoring have been positively associated

with important career outcomes such as promotions (Dreher &

Ash, 1990; Wayne, Liden, Kraimer, & Graf, 1999), income (Dre-

her & Ash, 1990), intrinsic job satisfaction (Chao et al., 1992), and

career commitment (Allen et al., 2004). We propose that both

career and psychosocial mentoring received in developmental re-

lationships will relate to graduate students’ professional identifi-

cation.

Career mentoring. Career development support, or career

mentoring, enhances protégé advancement in an organization or in

their career and includes functions such as sponsorship, exposure

and visibility, coaching, protection, and providing challenging

assignments. This type of mentoring is representative of a serial

socialization tactic wherein mentors, acting as experienced mem-

bers of the profession, provide newcomers with clear guidelines

and structure that helps them to organize and make sense of their

1

Ashforth (2001) notes that the need for control is conceptually similar

to the need for autonomy (McClelland, 1985) and the need for belonging

is similar to the need for affiliation (McClelland, 1985). However, Mc-

Clelland’s needs are most often characterized as individual differences—

individuals have consistently high or low desires for each—whereas Ash-

forth’s (2001) psychological motives for control and belonging are variable

and role specific, therefore warranting different terminology to distinguish

the motives from the individual differences.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

42

GRECO AND KRAIMER

new role (Van Maanen & Schein, 1979). In addition, Kram (1985)

described helping the protégé develop a sense of professional

competence and achieving long-term career goals as a primary

career mentor function.

Identity in a new role is often tied to concerns about competence

(Kram, 1985). Ashforth (2001) proposes that one of the psycho-

logical needs that newcomers seek to satisfy when entering a new

role is a need for control. As mentioned previously, the need for

control is defined as a need for agency and mastery in one’s role

and includes concepts related to competence, autonomy, self-

determination, and power. The premise of this motive is that when

one has control over one’s role, this creates a sense of involvement

and responsibility and allows one to more fully internalize the new

role identity. Ashforth (2001) notes that this motive answers the

question of “how”—how do I enact the new role?

Efforts to clarify one’s identity in terms of how to perform

competently are facilitated by career mentoring. Newcomers to a

role fulfill the need for control by obtaining information and

feedback about role requisite knowledge, expectations, and values

from more experienced members. In the process of mastering the

role (i.e., feeling control), the newcomer learns and develops skills

and knowledge on how to behave in role-appropriate ways. Career

mentoring exemplifies control in that an experienced colleague,

through coaching, is providing information, feedback, and support

to help the newcomer better understand the values, expectations,

and appropriate behaviors of the graduate program and profession

more broadly. Through exposure to challenging assignments, ca-

reer mentoring provides a newcomer with experiences that help

him or her develop professional knowledge and skills (i.e., in-

crease professional competencies). Satisfying this control motive

is also consistent with themes from social identification theory as

a mentor can help a newcomer shape him or herself in ways

consistent with in-group classification (Tajfel, 1978). A sense of

control over a role identity engendered by coaching from a mentor

enables one to own the identity and to more fully adopt it as an

authentic expression of the self. As such, fulfilling this motive

answers the question of “how” the newcomer can engage with the

new role and experience the power and success of one’s mentors

as one’s own.

Hypothesis 1: Career mentoring positively predicts profes-

sional identification.

Psychosocial mentoring. Psychosocial mentoring addresses

interpersonal aspects of the relationship between mentor and pro-

tégé and includes functions such as serving as a role model and

providing counseling, friendship, and advice (Kram, 1985). Psy-

chosocial mentoring is consistent with investiture socialization

tactics wherein experienced organizational members act as role

models for new recruits and provide positive social support (Van

Maanen & Schein, 1979). Whereas career mentoring is expected to

fulfill motives for control, psychosocial mentoring is expected to

fulfill motives for belonging. The motive for belonging is defined

broadly as a desire for attachment with others in a new role as well

as the desire to be a part of a community that shares common

interests (Ashforth, 2001; Bowlby, 1988; Brewer, 1993). This

motive answers the question of “who”—who shares this identity

with me?

When transitioning into a new role, the belonging motive is tied

to positive value judgments about one’s self relative to a target

social group. Drawing from sociometer theory (Leary & Baumeis-

ter, 2000), Ashforth (2001) proposes that social inclusion and a

sense of belonging enhance self-esteem, leading to identity con-

struction consistent with the referent group (e.g., Vignoles, Rega-

lia, Manzi, Golledge, & Scabini, 2006). This corresponds with

social identity theory wherein perceived group membership arises

out of a social comparison process where individuals differentiate

between in-group members similar to the self and out-group mem-

bers who are different from the self as a way to enhance self-

esteem (Tajfel & Turner, 1985). Psychosocial mentoring is ex-

pected to positively relate to professional identification because

psychosocial mentoring fosters attachment, or belonging, with

senior colleagues in the profession, which develops the newcom-

er’s self-concept (Kram, 1985). Psychosocial mentoring can build

self-esteem and interpersonal belonging in several ways. Through

serving as a role model, the mentor sets a desirable example that

the newcomer identifies with as representative of the profession.

Accompanied with acceptance and confirmation from the mentor,

the newcomer sees an idealized self in the mentor that allows one

to have a positive appraisal of one’s own value and viability as a

member of the group to which one aspires to belong. The more

psychosocial mentoring one receives (i.e., acceptance and confir-

mation, friendship, and counseling), the more likely that individual

will understand and feel similar to others in the profession, which

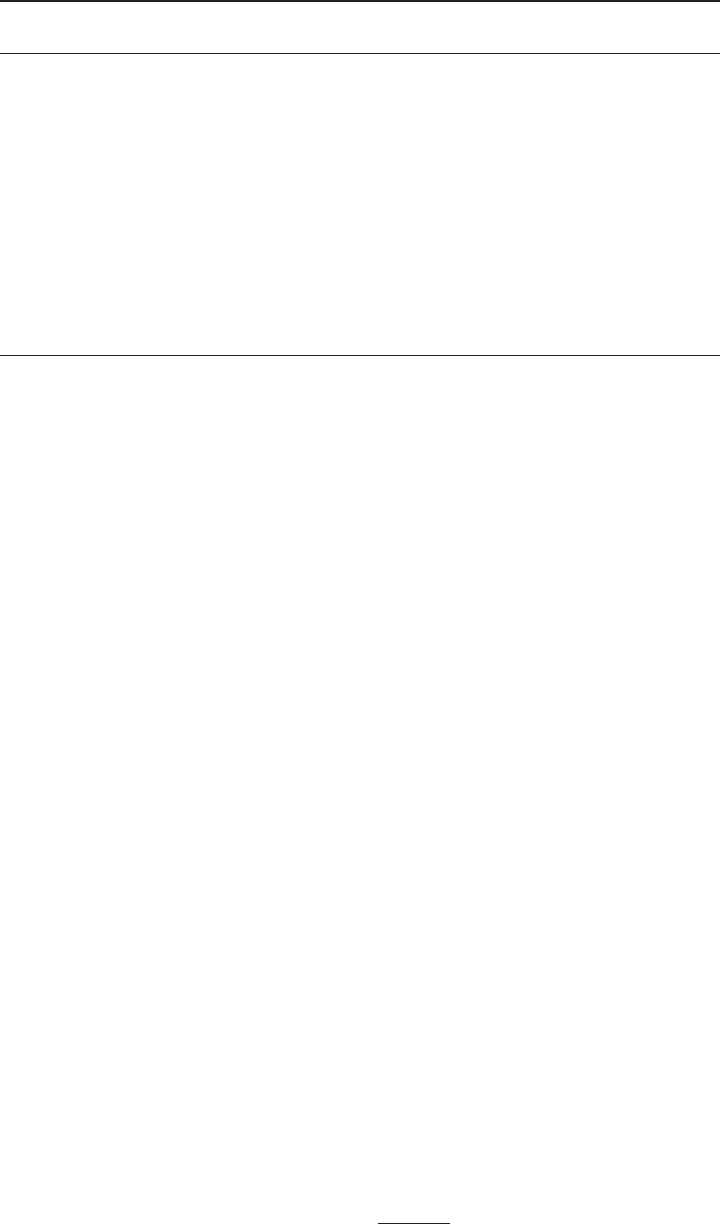

Figure 1. Partially mediated model of mentoring to short-term career goals through professional identification.

ⴱ

p ⬍ .05.

ⴱⴱ

p ⬍ .01.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

43

MENTORING, IDENTIFICATION, AND CAREER GOALS

increases feelings of self-esteem and in-group belonging. As such,

fulfilling the belonging motive answers the question of “who” the

newcomer shares an identity with and represents a positive eval-

uation of the future self (Leary & Baumeister, 2000). Therefore,

higher levels of psychosocial mentoring will relate to higher levels

of professional identification.

Hypothesis 2: Psychosocial mentoring positively predicts pro-

fessional identification.

Professional Identification and Career Goals

For goal outcome variables, we focus on goal content (i.e.,

extrinsic and intrinsic) and goal quality based on the findings from

the pilot study (available as an online supplemental materials) and

as a reflection of social identification theory and the broader goal

setting literature. We also further differentiate between short- and

long-term goals based on goal setting theory. Latham and Seijts

(1999) along with Bandura and Schunk (1981) argue that a key

motivational component in goal setting relies on setting both

short-term (i.e., proximal) and long-term (i.e., distal) goals. Short-

term goals, sometimes referred to as subgoals, allow individuals to

reframe complex long-term goals into smaller, more attainable

steps that increase the chance for feedback and strategy adjustment

in pursuit of long-term goals (Latham & Seijts, 1999; Seijts &

Latham, 2001). Research shows that when learning and motiva-

tion, as opposed to just motivation, are required for goal attain-

ment, then both short- and long-term goals are necessary for goal

attainment (Bandura & Simon, 1977; Morgan, 1985; Stock &

Cervone, 1990). Although we believe that both short- and long-

term goals are important outcomes of the mentoring process, there

is no theoretical rationale supporting differential relationships be-

tween professional identification and short- versus long-term

goals. Therefore, although we test the proposed model separately

for short- and long-term goals, we develop our hypotheses refer-

ring simply to “goals.”

Goal content can be broadly categorized into extrinsic/intrinsic

categories (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Extrinsic goals are defined as the

extent to which the individual’s career goals include “extrinsically

motivating attributes such as visible success, status and influence

within the organization or society, and high financial rewards”

(Seibert et al., 2013, p. 171). Extrinsic goals have an outward

orientation (Williams, Hedberg, Cox, & Deci, 2000) that reveal a

concern with external signs of self-worth and interpersonal com-

parison with others (Kasser & Ryan, 1996). Intrinsic goals are

defined as goals that include intrinsically motivating features such

as “continually gaining new skills and knowledge, having inter-

esting and challenging work, and having the opportunity to do

work that impacts society” (Seibert et al., 2013, p. 171). Intrinsic

goals are consistent with actualizing and growth tendencies and are

expected to satisfy basic and inherent psychological needs for

relatedness, competence, and growth (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Such

goals are expected to be inherently satisfying or valuable to an

individual and are not reliant on the contingent evaluation of others

(Kasser & Ryan, 1996).

Importantly, Deci and Ryan (2000) note that the content (ex-

trinsic vs. intrinsic) of goals is distinct from the motives for goals,

which are related to the reasons why people are pursuing the

particular goal. The authors argue that motivations for pursuing a

goal can range from being self-determined with little to no external

pressure, to completely controlled by external pressures. Further,

intrinsic or extrinsic goal content is not necessarily related to a

particular goal motive (self-determined vs. controlled). For exam-

ple, it is possible that early career academics may set an extrinsic

goal to get a job at a prestigious university because they personally

value the resources and opportunities associated with prestigious

universities (self-determined motive) or because they feel pressure

from graduate advisors to pursue a research career at a prestigious

university (controlled motive). Consistent with previous work

(e.g., Seibert et al., 2013), we focus only on the content of the goal

itself, rather than the potential motivation behind the goal, treating

intrinsic and extrinsic career goals as distinct, theoretically orthog-

onal constructs.

Goal content-extrinsic. The content of extrinsic goals in-

cludes status and financial outcomes, those that primarily entail

social recognition or approval of others or material rewards

(Kasser & Ryan, 1996; Seibert et al., 2013). The high public status

of the professions is unquestioned in nearly all data on occupa-

tional prestige (Abbott, 1981, 2014; Featherman & Hauser, 1976;

Nakao & Treas, 1994). The main argument is that wealth and

status are universally and highly valued in any society, so powerful

occupations are highly regarded by all individuals (Treiman,

2013). Studies have found that business and law students identified

with their chosen profession because the profession represented

the ability to have the salary and lifestyle associated with higher

earnings (Schleef, 2000). Other studies have shown that students

entering business and law professions identified with their chosen

occupation, not because they had high perceived self-aptitude, but

because the profession represented the ability to have the prestige

(Azizzadeh et al., 2003; Schleef, 2000) and social status (Gran-

field, 1992) associated with the profession. Thus, external markers

such as income and status are a crucial basis for authenticating

professional membership.

Self-verification theory can explain why those who identify

more with the profession are more likely to set goals with extrinsic

content. According to self-verification theory, people desire veri-

fication of their core self-views (Swann, 1983; Swann & Read,

1981

). Motivated by desires for consistency and stability, individ-

uals

strive to maintain consistent self-views and chronically rein-

force them through a variety of social processes. Specifically,

individuals prefer others to see them as they see themselves

(Swann, Stein-Seroussi, & Giesler, 1992) and seek out interactions

with others that reinforce their self-concept. The extent to which

people see professional identity as a significant part of their

self-conception is reflected by how much they identify with the

group (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). If early career professionals have

high levels of identification with the profession, they regard this

profession-based self-view as an indispensable part of their self.

To verify their self-view as professional group members, early

career professionals may set extrinsic goals consistent with char-

acteristics of the profession, such as extrinsic signs of status and

wealth. External goals represent “identity cues” that are highly

identifiable signs and symbols of the profession (e.g., Pratt &

Rafaeli, 1997). By setting goals that represent acquisition of signs

and symbols of who they are as professional members, extrinsic

goals allow early career professionals to verify their own sense of

self.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

44

GRECO AND KRAIMER

Hypothesis 3: Professional identification positively predicts

extrinsic goals.

Goal content-intrinsic. Individuals with intrinsic career goals

seek opportunities to learn and grow, they aspire to gain knowl-

edge through challenging work. Kasser and Ryan (1996) conclude

that a defining characteristic of intrinsic goals is that they are

inherently valuable or satisfying, rather than being dependent on

the contingent evaluations of others.

Many professions have stated purposes that align with intrinsic

ideals. For example, medical schools emphasize the importance of

helping those in need, business schools emphasize the goal of

improving workers’ lives and the economy, and education schools

emphasize the goal of improving society. These ideals are widely

endorsed by society and likely play some role for professionals in

entering their chosen programs. Studies of law students indicate

that some students enter law school for altruistic reasons, such as

wanting to help people and improve society through social justice

(Granfield, 1992; Schleef, 2000). Further, most professional fields

offer intellectually stimulating work based on years of advanced

education, suggesting that professionals find some degree of chal-

lenging work personally fulfilling. Even if professional students do

not have intrinsic motivations prior to entering the profession, to

the extent that they internalize professional standards and norms

through identification with the role, they will develop intrinsic

goals that reflect professional standards of conduct as part of the

self-verification process. Through adopting the perspective that

altruistic and intrinsic goals are important for professionals, early

career professionals are able to see themselves as others see them

(Swann, 1983). High levels of professional identification will then

positively relate to individual intrinsic goals because the profes-

sional role presents an opportunity to do meaningful and challeng-

ing work that also has the potential to have a positive impact on

others.

Hypothesis 4: Professional identification positively predicts

intrinsic goals.

Goal quality. Goal quality is represented by goals that align

with the primary tenets of goal setting theory, that is, career goals

that are difficult, specific, and to which individuals are committed.

Specific and difficult goals and goal commitment are the primary

features of effective goals within goal setting theory; such goals

are better at directing energy and attention necessary for goal

attainment (Locke & Latham, 1990, 2002). Early career profes-

sionals who identify with the profession are likely to set high

quality goals as part of the self-verification process which, at its

core, is based on uncertainty reduction. Individuals like to feel that

their social world is “knowable and controllable” (Swann, 1983,p.

34) and are motivated to see to it that neither their self-conceptions

nor the appraisals of others in relation to their self change in any

drastic way. When early career professionals identify with the

profession, they are likely to have a clear idea of what constitutes

success for professional members and are likely to model their

career goals after clear indications of success as a way to verify

their status as a professional member. High quality goals are clear

and specific and thus reduce uncertainty associated with variation

in self-concepts related to the professional identity.

In terms of goal difficulty, individuals high in professional

identification should set goals that reflect the high standards that

are prototypical of professional communities, thus those goals are

likely to be difficult to attain. Difficult goals are also those which

may be most visible to others (e.g., publications in high status

journal) and, as such, have the potential to act as identity cues

which can communicate the identity to others and support self-

verification processes. Finally, goal commitment is created be-

cause social identification theory suggests that if one identifies

with the profession then he or she will be more committed to

actions that maintain belonging to the group and verify identity as

a group member. As a result, high levels of professional identifi-

cation should lead to commitment to goals shaped by the profes-

sion.

Hypothesis 5: Professional identification positively predicts

goal quality.

Both career mentoring and psychosocial mentoring are expected

to be positively related to extrinsic and intrinsic goal content and

goal quality through professional identification. Professional iden-

tification is a key mediating variable between mentoring and

career goals because it reflects the degree to which the professional

role is subjectively important to role occupants (Ashforth, 2001)

and reflects views that a primary mentor function is to help the

protégé develop a sense of professional competence and achieve

career goals (Kram, 1985). Mentoring experiences provide the

foundation for professional expectations (e.g., goals; Noe et al.,

1990), but the extent to which those expectations are translated

into personal goals depends on whether professional standards are

internalized through professional identification. In other words, the

more one internalizes mentoring ideals through professional iden-

tification, the more likely he or she is to have intrinsic and extrinsic

goals (consistent with professional standards) and goals of high

quality. Goals are the future enactment of professional identities

(Ashforth, 2001) developed from mentoring experiences (Tenen-

baum, Crosby, & Gliner, 2001).

Hypothesis 6: The relationship between (a) career mentoring

and (b) psychosocial mentoring and goal outcomes (i.e., in-

trinsic goals, extrinsic goals, goal quality) is mediated by

professional identification.

Method

Sample and Procedure

Survey data was collected from graduate students in profes-

sional programs in the United States as recorded in the University

of Iowa’s IRB# 201507760: Career Goals and Professional Iden-

tification: Goal Setting in the Role Transition Process. Schools

were contacted based on their conference division in order to target

universities with large and diverse graduate programs; universities

from the Big 10, Big 12, Pac 12, and SEC were included in our

initial contact efforts. Links to the online survey were distributed

through e-mail. There were three surveys in total, each separated

by approximately 4 weeks. The purpose of collecting data over

three surveys was to reduce systematic errors related to common

method variance (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff,

2003). Invitations to complete the first online survey were distrib-

uted in two ways. First, we identified graduate program coordina-

tors from university websites and emailed asking them to forward

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

45

MENTORING, IDENTIFICATION, AND CAREER GOALS

the link to the first online survey to their graduate students. In total,

we e-mailed 388 graduate coordinators. Second, when e-mail

addresses for students were available on university websites, we

e-mailed the students directly with a link to the first online survey;

we directly e-mailed 3,635 students.

Survey 1 contained measures for career and psychosocial men-

toring, potential control variables, and demographics. Survey 2,

sent 4 weeks later, contained measures of professional identifica-

tion, open-ended questions for short-term goals and scale items for

short-term goal content (i.e., extrinsic and intrinsic) and goal

quality (i.e., specific, difficult, commitment). Short-term goals

were defined as “occupational goals that you hope to achieve soon

after graduation.” Survey 3, sent another 4 weeks later, contained

open-ended questions for long-term goals and scale items for

long-term goal content (i.e., extrinsic and status) and goal quality

(i.e., specific, difficult, commitment). Long-term goals were de-

fined as “occupational goals that you hope to achieve one day in

your career.”

In total, 704 graduate students responded to Survey 1; however,

a significant number only filled out part of the survey. After

eliminating respondents who did not provide an e-mail address

(which was necessary to send the follow-up surveys) and those

with missing data on a majority of study variables, the final sample

size was 480 respondents to Survey 1. Because graduate coordi-

nators forwarded the survey link to an unknown number of grad-

uate students, it is not possible to calculate a response rate. Invi-

tations to complete the second and third surveys were distributed

directly to the 480 graduate students who responded to Survey 1.

In total, 343 students responded to Survey 2 (71.4% response rate

of Survey 1 respondents) and 331 students responded to Survey 3

(68.9% response rate of Survey 1 respondents). After removing

participants with missing data on focal variables, the final sample

size was 312 for testing the model using short-term goals (short-

term goal [STG] model) and 243 for testing the model using

long-term goals (long-term goal [LTG] model).

Respondents were enrolled in programs from 28 different uni-

versities. Approximately one quarter (23.6%) of respondents were

enrolled in Master’s programs (e.g., MA, MS, MLS), while the

remaining three quarters (76.4%) of respondents were enrolled in

PhD programs or equivalent (e.g., PhD, Ed.S, MD/PhD). The

respondents represented a large variety of program fields: The 17

fields were subsequently categorized into “hard” and “social”

sciences. Hard sciences included about half of respondents

(53.2%) from the following fields: engineering/computer science,

health/medicine, biological and physical sciences, agricultural or

animal sciences, architecture, mathematics, chemistry, and astron-

omy. Social sciences (46.8%) included respondents from the fol-

lowing fields: arts/humanities, business, communication, educa-

tion, government, law/public policy/criminal justice, psychology/

social science, and library science. Programs ranged from 1 to 8

years, the mean program length was 4.45 years. Respondents had

been enrolled in their programs from .23 to 8 years and the mean

time in the program was 2.08 years.

2

A majority of respondents

(86.7%) were on track to finish on time. Students had a variety of

financial support including teaching assistantships (49.5%), re-

search assistantships (53.8%), and/or grants (19.8%).

The age of respondents ranged from 21 to 63 years, with a mean

age of 28.14 years; 54.6% of respondents were female; 6.4%

indicated they were of Hispanic origin. A majority of the sample

was Caucasian (75.2%), and the remaining respondents identified

as Asian (16.2%), African American (2.9%), Indian (2.4%), and

other (3.3%). About one quarter (24.6%) of respondents were

international students. Approximately half of the respondents were

married or living with a committed partner (57%) and the majority

did not have children (88.9%).

Measures

All measures were self-reported and items were measured on a

5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree)to5

(strongly agree) unless otherwise noted.

Mentoring. Both career mentoring and psychosocial mentor-

ing scales were from the shortened version of Dreher and Ash

(1990) reported in Kraimer, Seibert, Wayne, Liden, and Bravo

(2011) and contained four items each. Responses range from 1 (not

at all)to5(to a very large extent). Example items for career

mentoring ask to what extent faculty advisor(s) have “given or

recommended you for challenging assignments that present oppor-

tunities to learn new skills” and “given or recommended you for

assignments that helped you meet new colleagues.” Items were

averaged to create a single scale score (␣⫽.90). Examples of

psychosocial support include items such as the extent to which

advisor(s) have “conveyed empathy for the concerns and feelings

you have discussed with him/her” and “encouraged you to talk

openly about anxiety, fears, or concerns you have that may detract

from your work.” Items were averaged to create a single scale

score (␣⫽.89).

Professional identification. Professional identification was

measured using five items from Hekman et al. (2009). Example

items are “In general, when someone praises my profession, it

feels like a personal compliment” and “My field’s successes are

my successes.” Items were averaged to create a single scale score

(␣⫽.74).

Goal content. The extrinsic content of goals was assessed

with eight items: five scale items from Seibert et al. (2013) edited

to fit the academic context (e.g., replacing “company” with

“field”) and three additional items. Example items from Seibert et

al. (2013) are “It is important to me to achieve financial success in

my career” and “It is important for me to be seen by others as a

success in my career.” The three additional items were: “A high

income is one of my career goals”; “One’s success in this career

can be judged by the amount of money one makes”; and “Rank and

status are important to me in my career.”

Intrinsic goals were measured with seven items: five scale items

from Seibert et al. (2013) and two additional items. Example items

from Seibert et al. (2013) are “I want to have a positive impact on

other people or social problems through my work” and “It is

important for me to continue to learn and grow over the course of

my career.” The two additional items were “I want to do work that

is important and meaningful” and “I want to have a positive impact

on organizations and society through my work.” Extrinsic and

intrinsic goals were measured twice, once with respect to short-

2

As a robustness check for potential outliers in the sample, we also ran

our analyses removing six respondents who had been in their programs 6

or more years and indicated they were not on track to finish on time. The

analyses with this reduced sample did not substantively change results of

the hypothesis testing, thus, we retained all respondents in the analyses.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

46

GRECO AND KRAIMER

term goals in Survey 2 and once for long-term goals in Survey 3.

Instructions on the respective surveys asked respondents to think

about their short- or long-term goals and asked them to rate the

extent they agreed with the items with reference to their goals.

Items were averaged to create a single scale score for short-term

extrinsic (␣⫽.82), short-term intrinsic (␣⫽.78), long-term

extrinsic (␣⫽.81), and long-term intrinsic (␣⫽.84) goals.

Goal quality. On Survey 2, respondents were asked to gen-

erate short-term goals. These goals were explained as goals that

one hoped to achieve soon after graduation, such as getting a

particular type of job or getting a job at a particular university/

institution. On Survey 3, respondents were asked to generate

long-term goals. These goals were explained as occupational goals

that one hopes to achieve someday in his or her career, or goals

representing more distant occupational aspirations. We asked re-

spondents to list two short-term goals (Survey 2) and two long-

term goals (Survey 3), as this was the average of the open-ended

request for self-reported goals from the Pilot Study (included as an

online supplement). Across the respondents, a total of 626 short-

term goals and 519 long-term goals were reported.

After each open-ended goal, respondents replied to statements

related to goal difficulty, goal specificity, and goal commitment.

Goal difficulty was measured with two items from Steers (1976).

The items were “This goal will require a great deal of effort from

me to complete” and “This goal is quite difficult to attain.” Goal

specificity was measured with two questions from Steers (1976);

the two items were “This goal is very clear and specific” and “I

have a clear sense of how to achieve this career goal.” Goal

commitment was measured using two items from Hollenbeck,

Klein, O’Leary, and Wright (1989): “I am strongly committed to

pursuing this goal” and “It would take a lot to make me abandon

this goal.”

Before creating scale scores for goal quality, two raters inde-

pendently coded all self-reported short- and long-term goal state-

ments in terms of professional relevance (1 ⫽ relevant; 0 ⫽ not

relevant). The two raters had a moderate level of agreement based

on guidelines from Altman (1999) and adapted from Landis and

Koch (1977), Cohen’s ⫽.58; any disagreements were resolved

through discussion. The purpose of this coding was to remove any

goals that were not professionally relevant when creating the goal

quality score. Of the short-term goals, 38 were deemed not rele-

vant (e.g., “To get a great job in Seattle, Washington”); of the

long-term goals, 20 were deemed not relevant (e.g., “I want to own

and operate my own airplane by age 40”). The dummy code for the

relevancy of the goal (1 or 0) was then multiplied by the average

of the goal difficulty, specificity, and commitment items for each

goal and all 0 values were subsequently marked as missing data in

the analysis. In this way, the score for goal quality excludes goals

that were not professionally relevant.

The relationship between the higher order goal quality construct

and the three first-order dimensions was assessed with a second-

order confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). A model was specified

in which first-order factors for difficulty, specificity, and commit-

ment was predicted by a higher-order goal quality construct;

because each first-order factor related to two distinct goals, errors

were correlated between items assessing the same goal. The STG

model demonstrated moderately good fit (

2

⫽ 190.56; RMSEA ⫽

.10; CFI ⫽ .86; SRMR ⫽ .07) and each factor loaded onto the

hypothesized goal quality variable (␥

difficulty

⫽ .86, p ⫽ .00;

␥

specificity

⫽ .79, p ⫽ .00; ␥

commitment

⫽ .94, p ⫽ .00). The fit of

the second-order model exhibited significantly better fit than a

single-factor model (⌬

2

⫽ 10.84, ⌬df ⫽ 3, p ⬍ .05). Credé and

Harms (2015) recommend providing the average variance ex-

tracted (AVE) which summarizes the ability of the higher-order

factor to account for variance in the lower-order factors; the AVE

for the STG model was .75, which surpasses the recommended

value of .50 (Credé & Harms, 2015; Johnson, Rosen, Chang,

Djurdevic, & Taing, 2012; Johnson, Rosen, & Djurdjevic, 2011).

The LTG model demonstrated good fit (

2

⫽ 126.62; RMSEA ⫽

.09; CFI ⫽ .91; SRMR ⫽ .06) with each first order factor signif-

icantly loading onto the goal quality variable (␥

difficulty

⫽ .45, p ⫽

.00; ␥

specificity

⫽ .79, p ⫽ .00; ␥

commitment

⫽ .96, p ⫽ .00). The fit

of the second-order model exhibited significantly better fit than a

single-factor model (⌬

2

⫽ 19.20, ⌬df ⫽ 3, p ⬍ .05) and the AVE

for the second-order factor model was .58. Although some of the

fit indices are slightly below recommended cut-off points for

“acceptable fit,” the model comparisons, AVE scores, and corre-

lations among the dimensions (r ranges from .38 to .58 for short-

term goals and from .36 to .76 for long-term goals) suggest the

dimensions can be represented by a single overall construct, goal

quality. Both short-term (␣⫽.80) and long-term (␣⫽.77) goal

quality demonstrated adequate levels of reliability.

Control variables. We included two relevant control vari-

ables following recommended guidelines (Aguinis & Vanden-

berg, 2014; Becker, 2005; Bernerth & Aguinis, 2016). First, we

included whether expectations about the profession were met as

a control variable based on Ashforth’s (2001) model of identi-

fication. Ashforth (2001) positions “met expectations” as a

precursor to identity-related processes and subsequent identifi-

cation; the rationale is that newcomers have certain expecta-

tions about new roles, and when these expectations do not

match reality, they can experience reality shock which affects

subsequent identification processes (Ashforth, 2001; Major,

Kozlowski, Chao, & Gardner, 1995). We measured met expec-

tations with two items measured on Survey 1: “To what extent

have your expectations about the profession been met” and “All

in all, have your expectations with regard to the profession been

met” (␣⫽.89, Arnold & Feldman, 1982; Lee & Mowday,

1987). Second, we controlled for the length of time the student

had been in their graduate program because both career goals

and mentoring experiences are likely to differ significantly

between the beginning and end of a graduate student’s tenure

(e.g., Humberd & Rouse, 2016). We considered other control

variables such as the program field (hard vs. social science),

age, gender, and whether the respondent was an international

student, but these variables did not affect the results in a

meaningful way. Therefore, we include these variables in the

correlation table but not in further analyses.

Results

The means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among con-

trol and study variables are shown in Table 1. Both career mentoring

(r ⫽ .20) and psychosocial mentoring (r ⫽ .30) are positively related

to professional identification. In turn, professional identification is

positively related to all short-term (r

extrinsic

⫽ .30; r

intrinsic

⫽ .24;

r

quality

⫽ .20) and long-term goal (r

extrinsic

⫽ .27; r

intrinsic

⫽ .26;

r

quality

⫽ .21) variables.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

47

MENTORING, IDENTIFICATION, AND CAREER GOALS

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

We first conducted a CFA, using Mplus 7.2, to assess the extent

to which scale items captured intended constructs. When con-

structs had more than six items as indicators we created parcels.

Given the large number of items relative to sample size in the

current study, parcels enabled us to maintain a better sample

size-to-parameter ratio and decreased the likelihood of identifica-

tion problems in the CFA (Williams & O’Boyle, 2008). Parcels

were created using the item-to-construct balance approach pre-

sented in Little, Cunningham, Shahar, and Widaman (2002) with

the exception of the parcels for the goal quality variable. Goal

quality is multidimensional and comprised of distinct subscales

(i.e., difficulty, specificity, commitment), so items from each sub-

scale were grouped into conceptually relevant parcels; this maxi-

mizes the internal consistency of each parcel for multidimensional

latent variables (Williams & O’Boyle, 2008).

For the hypothesized models, we performed two separate CFAs,

one using short-term goals (the STG model), and the other using

long-term goals (the LTG model). Each item or parcel was fit to its

relative factor. In the CFA for both models, a total of six constructs

were included in each analysis: career mentoring (four items),

psychosocial mentoring (four items), professional identification

(five items), short-/long-term goal content-extrinsic (three parcels

each), short-/long-term goal content-intrinsic (three parcels each),

short-/long-term goal quality (three parcels each). All factor load-

ings on the specified factors were significant, which indicates that

the items and parcels were acceptable indicators for the designated

latent variables.

For the STG model, the hypothesized six-factor model demon-

strated good fit (

2

⫽ 374.15; RMSEA ⫽ .05; CFI ⫽ .94;

SRMR ⫽ .05). A test of alternative models showed that the

hypothesized model had better fit than a five-factor model where

career mentoring and psychosocial mentoring were modeled as a

single “mentoring” variable (⌬

2

⫽ 509.79, ⌬df ⫽ 1, p ⬍ .01), a

five-factor model where extrinsic and intrinsic goal content vari-

ables were combined into a single goal content variable (⌬

2

⫽

353.76, ⌬df ⫽ 1, p ⬍ .01), or a four-factor model where all goal

variables were combined into a single factor (⌬

2

⫽ 406.49,

⌬df ⫽ 3, p ⬍ .01).

For the LTG model, the hypothesized six-factor model demon-

strated good fit (

2

⫽ 363.06; RMSEA ⫽ .06; CFI ⫽ .94;

SRMR ⫽ .06). A test of alternative models showed that the

hypothesized model had better fit than a five-factor model where

career mentoring and psychosocial mentoring were modeled as a

single “mentoring” variable (⌬

2

⫽ 436.58, ⌬df ⫽ 1, p ⬍ .01), a

five-factor model where extrinsic and intrinsic goal content vari-

ables were combined into a single goal content variable (⌬

2

⫽

251.87, ⌬df ⫽ 1, p ⬍ .01), or a four-factor model where all goal

variables were combined into a single factor (⌬

2

⫽ 316.44,

⌬df ⫽ 3, p ⬍ .01).

We also computed the AVE estimates for the 10 scales (Fornell

& Larcker, 1981); the AVE estimate is the average amount of

variation that a latent construct is able to explain in the observed

variable to which it is theoretically related (Farrell, 2010). For the

control variable, AVE was .80 for met expectations. For the model

variables, AVE values were .55 for career mentoring, .56 for

psychosocial mentoring, .39 for professional identification, .64 for

STG content–extrinsic, .59 for STG content–intrinsic, .31 for STG

quality, .62 for LTG content–extrinsic, .65 for LTG content–

intrinsic, and .32 for LTG quality. A purpose of calculating the

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study Variables

Variable MSD公AVE1 2 3456789101112131415

1. Gender .45 .50 — —

2. Age 28.14 5.81 — .06 —

3. International

student .25 .43 — .24

ⴱⴱ

⫺.02 —

4. Program field .47 .50 — ⫺.01 .16

ⴱⴱ

.00 —

5. Met expectations 3.81 .86 .89 .08 ⫺.02 .09 .01 .88

6. Time in program

(in years) 2.05 1.69 — ⫺.06 .28

ⴱⴱ

⫺.02 .01 ⫺.22

ⴱⴱ

—

7. Career

mentoring 3.13 1.09 .74 .08 ⫺.05 .09 ⫺.01 .22

ⴱⴱ

⫺.03 .90

8. Psychosocial

mentoring 3.09 1.16 .75 ⫺.05 ⫺.02 .07 .10 .35

ⴱⴱ

⫺.09 .49

ⴱⴱ

.89

9. Professional

identification 3.57 .72 .63 ⫺.22

ⴱⴱ

⫺.06 .03 ⫺.02 .21

ⴱⴱ

⫺.12

ⴱ

.20

ⴱⴱ

.30

ⴱⴱ

.74

10. STG content-

extrinsic 3.43 .67 .80 ⫺.04 ⫺.07 .15

ⴱ

⫺.03 .06 ⫺.07 .13

ⴱ

.10 .30

ⴱⴱ

.82

11. STG content-

intrinsic 4.63 .37 .77 ⫺.16

ⴱⴱ

.02 ⫺.15

ⴱ

⫺.09 .07 ⫺.04 .08 .12

ⴱ

.24

ⴱⴱ

.14

ⴱ

.78

12. STG quality 3.89 .85 .56 ⫺.06 .04 ⫺.01 .12

ⴱ

.22

ⴱⴱ

.01 .05 .08 .20

ⴱⴱ

.21

ⴱⴱ

.16

ⴱⴱ

.80

13. LTG content-

extrinsic 3.42 .64 .79 ⫺.01 ⫺.12 .23

ⴱⴱ

⫺.01 .08 ⫺.04 .15

ⴱ

.14

ⴱ

.27

ⴱⴱ

.82

ⴱⴱ

.11 .10 .81

14. LTG content-

intrinsic 4.63 .43 .80 ⫺.11 .03 ⫺.20

ⴱⴱ

.00 ⫺.01 .04 .11 .06 .26

ⴱⴱ

.19

ⴱⴱ

.62

ⴱⴱ

.19

ⴱⴱ

.14

ⴱ

.84

15. LTG quality 3.88 .78 .57 ⫺.01 ⫺.03 .08 .12 .14

ⴱ

⫺.09 .17

ⴱⴱ

.10 .21

ⴱⴱ

.27

ⴱⴱ

.19

ⴱⴱ

.40

ⴱⴱ

.22

ⴱⴱ

.30

ⴱⴱ

.77

Note. N ranges from 312 (STG model), 243 (LTG model); STG ⫽ short-term goal; LTG ⫽ long-term goal; AVE ⫽ average variance extracted; values

in italics are alpha reliabilities. Gender is coded 0 ⫽ female, 1 ⫽ male; international student is coded 0 ⫽ no, 1 ⫽ yes; program field is coded 0 ⫽ hard

sciences, 1 ⫽ soft sciences. Variables 1–4 were potential control variables and are not included in model estimation.

ⴱ

p ⬍ .05.

ⴱⴱ

p ⬍ .01.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

48

GRECO AND KRAIMER

AVE is to establish discriminant validity in latent variables. Dis-

criminant validity is supported when the AVE of each construct is

greater than its shared variance (i.e., square of the correlation) with

any other construct (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) or, alternatively, the

square root of the AVE (公AVE) is greater than the raw correla-

tion; these values are presented in Table 1. For all but one of the

bivariate relationships the 公AVE is greater than the correlation.

The correlation between STG content-extrinsic and LTG content-

extrinsic is higher than the 公AVE value; however, hypothesis

testing is done separately for STG and LTG models, so there is no

need to demonstrate discriminant validity between these variables.

Hypothesis Testing

After assessing model fit of the measurement model, we tested

the theoretical model using structural equation modeling (SEM;

Mplus 7.2) with maximum-likelihood estimation. Any missing

data was coded as such in the data file; this analysis assumes that

data are missing completely at random, uses pairwise deletion

(Muthen & Muthen, 2007), and computes standard errors for

parameter estimates based on the observed information matrix

(Kenward & Molenberghs, 1998). We evaluate the model fit and

hypotheses independently for both STG and LTG models.

Short-term goal model. The hypothesized mediated model

using short-term goals fit the data well (

2

⫽ 512.94; RMSEA ⫽

.05; CFI ⫽ .93; SRMR ⫽ .06). The fit of the hypothesized STG

model was then compared with four alternative models as reported

in Table 2. The model comparisons were between the hypothesized

model and three partially mediated models that included direct

paths from the independent variables to the goal outcomes; each

detailed in Table 2. In models including paths from career men-

toring to goal outcomes (⌬

2

⫽ 3.19, ⌬df ⫽ 3, ns), psychosocial

mentoring to goal outcomes (⌬

2

⫽ 5.98, ⌬df ⫽ 3, ns), or both

mentoring to all outcomes (⌬

2

⫽ 7.42, ⌬df ⫽ 6, ns) there was no

significant difference in model fit. However, examination of the

individual paths showed a significant direct relationship between

psychosocial mentoring and the goal quality variable. Conse-

quently, we tested a final parsimonious model that included a path

from psychosocial mentoring to goal quality. Including this path

did significantly improve model fit from the hypothesized model

(⌬

2

⫽ 4.81, ⌬df ⫽ 1, p ⬍ .05). We report and interpret findings

from the partially mediated model (Model 5 in Table 2).

The results of the STG model are presented in Figure 1. Hypothesis

1 predicted a positive relationship between career mentoring and

professional identification, which was not supported (⫽.09, p ⫽

.27). Hypothesis 2 predicted a positive relationship between psycho-

social mentoring and professional identification, which was supported

(⫽.26, p ⬍ .01). Together, career and psychosocial mentoring

explained 17% of the variance (R

2

⫽ .17, p ⬍ .01) in professional

identification. Hypotheses 3 and 4 predicted a positive relationship

between professional identification and both STG content-extrinsic

and STG content-intrinsic, respectively. Both hypotheses were sup-

ported (

Extrinsic

⫽ .27, p ⬍ .01;

Intrinsic

⫽ .30, p ⬍ .01). Finally,

Hypothesis 5 predicted that professional identification would be pos-

itively related to STG quality, which was also supported (⫽.40,

p ⬍ .01).

Hypothesis 6 predicted that professional identification would

mediate the relationship between mentoring and career goals. The

indirect effects of the career and psychosocial mentoring on the

goal outcomes through professional identification are listed in

Table 3. None of the indirect effects from career mentoring to goal

outcome variables were significant, thus, Hypothesis 6a was not

supported. In contrast, the indirect effects of psychosocial mentor-

ing on STG content-extrinsic (.07), STG content-intrinsic (.08),

and STG quality (.10) were all significant (p ⬍ .05), providing

support for Hypothesis 6b. Lastly, in the partially mediated model,

psychosocial mentoring (⫽.17, p ⬍ .05) had a positive, direct

relation to STG quality. Variance explained for each of the goal

outcomes was: STG content-extrinsic (R

2

⫽ .07, p ⬍ .05), STG

content-intrinsic (R

2

⫽ .09, p ⬍ .05), and STG quality (R

2

⫽ .24,

p ⬍ .01).

Long-term goal model. The hypothesized mediated model

using long-term goals fit the data well (

2

⫽ 460.24; RMSEA ⫽

.05; CFI ⫽ .93; SRMR ⫽ .07). The fit of the hypothesized LTG

model was again compared to alternative path models as reported

in Table 2. In models including direct paths from career mentoring

to goal outcomes (⌬

2

⫽ 9.35, ⌬df ⫽ 3, p ⬍ .05) and psychosocial

mentoring to goal outcomes (⌬

2

⫽ 10.96, ⌬df ⫽ 3, p ⬍ .05) there

was significant improvement in model fit. Including paths from

Table 2

Structural Model Fit for Short- and Long-Term Goal Outcomes

Model

2

df RMSEA [90% CI] CFI SRMR ⌬

2

Short-term goal model

1. Fully mediated (hypothesized) 512.94 263 .05 [.04, .06] .93 .06

2. Partially mediated (career mentoring to all outcomes) 509.75 260 .05 [.04, .06] .93 .06 3.19

3. Partially mediated (psychosocial mentoring to all outcomes) 506.96 260 .05 [.04, .06] .93 .06 5.98

4. Partially mediated (both mentoring to all outcomes) 505.52 257 .05 [.04, .06] .93 .06 7.42

5. Partially mediated (psychosocial mentoring to goal quality) 508.13 262 .05 [.04, .06] .93 .06 4.81

ⴱ

Long-term goal model

1. Fully mediated (hypothesized) 460.24 263 .05 [.04, .06] .93 .07

2. Partially mediated (career mentoring to all outcomes) 450.89 260 .05 [.04, .06] .93 .06 9.35

ⴱ

3. Partially mediated (psychosocial mentoring to all outcomes) 449.28 260 .05 [.04, .06] .94 .06 10.96

ⴱ

4. Partially mediated (both mentoring to all outcomes) 446.61 257 .05 [.04, .06] .93 .06 13.63

ⴱ

5. Partially mediated (psychosocial mentoring to goal quality) 449.39 262 .05 [.04, .06] .94 .06 10.85

ⴱⴱ

Note. All models are compared to fully mediated model. RMSEA ⫽ root-mean-square error of approximation; CI ⫽ confidence interval; CFI ⫽

comparative fit index; SRMR ⫽ standardized root-mean-square residual.

ⴱ

p ⬍ .05.

ⴱⴱ

p ⬍ .01.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

49

MENTORING, IDENTIFICATION, AND CAREER GOALS

both types of mentoring to goal outcomes also significantly im-

proved model fit from the hypothesized model (⌬

2

⫽ 13.63,

⌬df ⫽ 6, p ⬍ .05). Examination of the individual paths suggested

that the improvement in fit was attributable to the direct relation-

ship between psychosocial mentoring and the goal quality variable

in particular. Thus, we ran a more parsimonious fifth model, where

psychosocial mentoring had a direct path only to LTG quality. This

model had a significant improvement in model fit over the hypoth-

esized model (⌬

2

⫽ 10.85, ⌬df ⫽ 1, p ⬍ .01). Therefore, we base

our interpretation for the LTG model on Model 5 (see Figure 2).

Hypothesis 1 predicted a positive relationship between career men-

toring and professional identification, which was not supported (⫽

.07, p ⫽ .42) and Hypothesis 2 predicted a positive relationship

between psychosocial mentoring and professional identification,

which was supported (⫽.28, p ⬍ .01). Together, career and

psychosocial mentoring explained 19% of the variance (R

2

⫽ .19, p ⬍

.01) in professional identification. Hypothesis 3 and 4 predicted a

positive relationship between professional identification and both

LTG content-extrinsic and LTG content-intrinsic, respectively. Both

hypotheses were supported (

Extrinsic

⫽ .23, p ⬍ .01;

Intrinsic

⫽ .22,

p ⬍ .01). Finally, Hypothesis 5 predicted that professional identifi-

cation would be positively related to LTG quality, which was not

supported by the data (⫽.19, p ⫽ .05).

The retained partially mediated model included a direct path

from psychosocial mentoring to LTG quality. This direct path,

along with the indirect effects of all independent variables on the

goal outcomes through professional identification are listed in

Table 3. The indirect effects test whether professional identifica-

tion mediates the relationship between mentoring and the LTG

outcomes per Hypothesis 6. The indirect effects from career men-

toring to all goal outcome variables were not significant. Thus,

Hypothesis 6a was not supported. In contrast, the indirect effects

of psychosocial mentoring on LTG content-extrinsic (.06, p ⬍ .05)

and LTG content-intrinsic (.06, p ⬍ .05) through professional

identification were significant. However, the indirect effect from

psychosocial mentoring to LTG quality (.05) was not. Thus, Hy-

pothesis 6b was supported with respect to LTG content, but not

quality. Lastly, in the partially mediated model psychosocial men-

toring (⫽.31, p ⬍ .01) had a positive, direct relation to LTG

quality. Variance explained for each of the goal outcomes was:

LTG content-extrinsic (R

2

⫽ .05, p ⫽ .12), LTG content-intrinsic

(R

2

⫽ .05, p ⫽ .12), and STG quality (R

2

⫽ .18, p ⬍ .01).

In summary, the methodological differences between the STG and

LTG models were the inclusion of short-term versus long-term goals

as outcomes and sample size (n ⫽ 312 vs. n ⫽ 243), respectively. We

found that a partially mediated model with a direct path from psy-

chosocial mentoring to goal quality fit the data best for both STG and

LTG models. There was consistency across both models; the primary

difference in findings was that psychosocial mentoring had direct and

indirect effects with goal quality in the STG model whereas it was

directly, but not indirectly, related to goal quality in the LTG model.

Supplementary Analysis

Although the hypothesized model proposed independent and

direct effects for career and psychosocial mentoring, we performed

several supplementary analyses to probe potential interactive or

compensatory effects of mentoring on professional identification.

3

First, it is unlikely that either career or psychosocial mentoring

functions occur completely independently of one another. The

effect of one mentoring function could be dependent on another,

suggesting the presence of a mentoring “profile” including both

mentoring functions. To test this premise, we modeled interactive

effects of career and psychosocial mentoring on professional iden-

tification, but the interaction term was not significant in the STG

(⫽⫺.03, p ⫽ .69) or LTG (⫽⫺.02, p ⫽ .67) models. This

suggests that there is not a particular mentoring profile that pre-