HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS

GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY,

SOUTH CAROLINA

CHICORA RESEARCH CONTRIBUTION 474

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD,

LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

Prepared By:

Michael Trinkley, Ph.D., RPA

Prepared For:

Mr. Eddie Yandle

N.B.T. of Columbia, Inc.

117 Beaver Ridge Dr

Elgin, SC 29045

CHICORA RESEARCH CONTRIBUTION 474

Chicora Foundation, Inc.

PO Box 8664

Columbia, SC 29202-8664

803/787-6910

www.chicora.org

July 9, 2007

This report is printed on permanent paper ∞

©2007 by Chicora Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this

publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or

transcribed in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior permission of Chicora

Foundation, Inc. except for brief quotations used in reviews. Full credit must

be given to the authors, publisher, and project sponsor.

i

ABSTRACT

In late June 2007 construction at a

proposed development about three miles west of

the City of Lexington in Lexington County, South

Carolina uncovered human remains. The

Lexington County Coroner and Sheriff’s

Department were notified in order to determine if

the remains represented a forensic case. The

coroner determined that the remains did not and

that they were more likely evidence of a “lost”

family graveyard. As a result the developer of the

property, N.B.T. of Columbia, Inc. requested that

Chicora Foundation become involved to

determine the size of the graveyard, the number of

individuals that might be present, and provide

recommendations.

This report provides background and

historical documentation concerning the

graveyard, including a detailed examination of

property records, period maps, aerial

photographs, and other historic documents.

As a result of this study it was determined

that the graveyard existed by at least 1927 when it

was perhaps a ¼ acre in size. It likely began

during the property’s ownership by David Drafts,

an African American farmer who purchased the

property in 1881. Between 1900 and 1905 Drafts

died and the property was partitioned to his seven

heirs, each receiving 8¾ acres. Each tract was

numbered sequentially from east to west, with the

graveyard falling on Tract 3.

This study completes the title search,

identifies a broad range of probable descendants,

and traces many through census and other

records. A kinship or lineage charge for three

generations has been prepared based on the

currently available information. This will assist in

the identification of probable descendants.

The study also attempted to identify death

certificates linked with the cemetery, which may

have been named Rawls or Strothers/Strathers.

Additional names are identified through this

process. We have also been provided with a list

thought to represent individuals reported to be

buried in the cemetery and an effort has been

made to link these names with the Drafts family.

Aerial imagery has been examined and it

is possible that the cemetery is shown on the 1959

and 1966 photographs. The cemetery, however, is

not shown on either the modern or 1946

topographic maps. It is also shown on the 1922

Lexington County soil survey. The absence of the

cemetery on these sources, however, is not

unusual.

An effort was made to contact family

members in the community. Phones calls,

however, have not been returned so it has not

been possible to include oral history accounts in

this study.

The historical evidence provides good

evidence of a cemetery, at least ¼ acre in size,

dating from perhaps the 1880s through the late

1950s. Although the cemetery may have suffered

some damage from logging in the early 1960s, we

have found no evidence of any extensive

disturbance prior to the clearing and grubbing

associated with the current development activities.

This study has identified a range of family names

likely associated with the cemetery, including

Anderson, Cortman (or Cartman), Crapps (or

Crappe, Trappe), Deshade, Drafts, Fields,

Gardner, Johnson, Robertson, Sheppard, and

Walker. Other possible names include Blackwell,

Corley, Isreal, Norris, Rawl, Richardson, Strother,

Summers, and Wise.

Additional investigations are on-going,

including the use of ground penetrating radar and

the metric and non-metric examination of skeletal

remains collected by the Lexington County

ii

Coroner and Sheriff.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Figures iv

List of Tables iv

Introduction 1

Historical Research 5

Title Research 5

Identified Plats and Maps 10

Aerial Photographs 11

Documented Burials 13

Reported Burials 15

Oral History 17

Conclusions 19

Penetrometer Study 13

Recommendations Regarding Other Preservation Issues 13

Sources Cited 23

Appendix 1. Resume for Michael Trinkley 25

iv

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure

1. Portion of the State of South Carolina map showing the project area 1

2. Portion of the Barr Lake USGS topographic map showing the development area 2

3. Graphic representation of the property title search 7

4. Plat of the study tract from 1974 8

5. Plat of the study tract from 2006 9

6. Portion of the 1946 Gilbert 15’ topographic map 10

7. 1943 aerial photograph of the project area 11

8. 1959 aerial photograph of the project area 12

9. 1966 aerial photograph of the project area 12

10. 1970 aerial photograph of the project area 13

11. 1006 aerial photograph of the project area 14

12. Lineage chart based on title research and examination of Federal census records 20

LIST OF TABLES

Table

1. Burials identified in the Rawl or Strother Cemetery from death certificates 13

2. Individuals reported to be buried on the property 15

INTRODUCTION

On June 20 construction crews excavating

utility lines at the Dawson’s Park development

about 3 miles west of the City of Lexington

uncovered human skeletal remains and notified

the Lexington County Coroner and Sheriff’s

Department. During the day-long investigation by

the Sheriff’s Department, which included

screening the spoil from the primary excavation,

additional remains were found about 100 feet to

the south in a second excavation. The coroner, Mr.

Harry Harmon, ordered a halt to the work until

additional assessment could be performed. The

coroner determined that the remains were not

forensic, but rather those of a family cemetery, and

requested that the developer of the property, Mr.

Edward D. Yandle of N.B.T. of Columbia, Inc.,

oversee the additional work.

It was at that time that Mr. Yandle

requested Chicora Foundation’s involvement to

examine the property and provide

recommendations regarding the size of the

cemetery.

Our initial investigation, by Ms. Julie

Poppell of the Chicora staff, was conducted on

June 22. The

excavations were still

open and it was clear

where the Sheriff’s

Department had been

screening spoil for the

recovery of remains.

Arrangements were

made for a more

careful inspection on

June 25.

1

On Monday,

June 25 the author, Dr.

Michael Trinkley,

visited the site with

staff members Nicole

Southerland and Julie

Poppell. The two

burials were identified

on the east side of

Dawson’s Circle, on

the west side of the

development. Burial 1,

which was more

complete and had been recovered by the Sheriff’s

Department from spoil, was apparently between

lots 156 and 157, although no evidence of the

burial pit was immediately evident. Burial 2,

represented by only a partial skull, had been

recovered from a different excavation, between

lots 153 and 154. No spoil had been screened in

this area and at the time of our visit there was no

clear evidence of a burial shaft or other remains.

Figure 1. Portion of the State of South Carolina 1:500,000 scale map showing the

Dawson’s Park project area in Lexington County.

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

2

An initial inspection did, however, reveal

scattered human remains on the surface from

Dawson’s Circle eastward for about 150 feet.

Remains did not appear to extend northward

across Dawson’s Drive, but did extend about 300

feet to the south. It appeared, based on this initial

survey, that remains were thinly spread over an

area of perhaps 200 by 400 feet, or about 1.8 acre.

These remains were flagged, numbered, and

collected. The locations were plotted by Mr.

Yandle’s surveyor for future use.

At that time we learned that the property

had been cleared and grubbed. This may account

for the presence of these remains, as well as their

dispersion on the surface. The area west of

Dawson’s Circle, about 80 feet in width,

apparently received placement of spoil. In

addition, there was a ca. 40 foot roadway which

had been cut down at least 1 foot and had been

heavily impacted by construction activities. These

areas were not examined at that time.

Figure 2. Portion of the Barr Lake USGS topographic map showing the development and graveyard area.

In an effort to identify additional burials

on the property, we initially used a penetrometer.

This is a device for measuring the compaction of

soil. When natural soil strata are disturbed –

whether by large scale construction or by the

excavation of a small hole in the ground – the

resulting spoil contains a large volume of voids

and the compaction of the soil is very low. When

this spoil is used as fill, either in the original hole

or at another location, it likewise has a large

volume of voids and a very low compaction.

In the case of a pit, or a burial, the

excavated fill is typically thrown back in the hole

not as thin layers that are then compacted before

the next layer is added, but in one, relatively quick

episode. This prevents the fill from being

compacted, or at least as compacted as the

surrounding soil.

Penetrometers come in a variety of styles,

INTRODUCTION

3

but all measure compaction as a numerical

reading, typically as pounds per square inch (psi).

The dickey-John penetrometer consists of a

stainless steel rod about 3-feet in length, connected

to a T-handle. As the rod is inserted in the soil, the

compaction needle rotates within an oil filled (for

damping) stainless steel housing, indicating the

compaction levels. The rod is also engraved at 3-

inch levels, allowing more precise collection of

compaction measurements through various soil

horizons. Two tips (½-inch and ¾-inch) are

provided for different soil types.

Of course, a penetrometer is simply a

measuring device. It cannot distinguish soil

compacted by natural events from soil artificially

compacted. Nor can it distinguish an artificially

excavated pit from a tree throw that has been

filled in. Nor can it, per se, distinguish between a

hole dug as a ditch and a hole dug as a burial pit.

What it does, is convert each of these events to psi

readings. It is then up to the operator to determine

through various techniques the cause of the

increased or lowered soil compaction.

For example, soils that have been

artificially compacted frequently exhibit

compaction levels that are significantly above

normal soil readings. And as for distinguishing a

burial pit from other, natural events, this is

typically done by carefully marking out the size,

shape, and orientation of the area of lesser

compaction.

While a penetrometer may be only

marginally better than a probe in the hands of an

exceedingly skilled individual with years of

experience, such ideal circumstances are rare. In

addition, a penetrometer provides quantitative

readings that are replicable and that allow much

more accurate documentation of cemeteries. In

fact, as will be discussed here, our research in both

sandy and clayey soils in Virginia, North Carolina,

South Carolina, and Georgia suggests very

consistent graveyard readings.

Like probing, the penetrometer is used at

set intervals along grid lines established

perpendicular to the suspected grave orientations.

The readings are recorded and used to develop a

map of probable grave locations. In addition, it is

important to “calibrate” the penetrometer to the

specific site where it is being used. Since readings

are affected by soil moisture and even to some

degree by soil texture, it is important to compare

readings taken during a single investigation and

ensure that soils are generally similar in

composition.

It is also important to compare suspect

readings to those from known areas. For example,

when searching for graves in a cemetery where

both marked and unmarked graves are present, it

is usually appropriate to begin by examining

known graves to identify the range of compaction

present. From work at several graveyards,

including the Kings Cemetery (Charleston

County, South Carolina) where 28 additional

graves were identified, Maple Grove Cemetery

(Haywood County, North Carolina) where 319

unmarked graves were identified, and the Walker

Family Cemetery (Greenville County, South

Carolina) where 78 unmarked graves were

identified, we have found that the compaction of

graves is typically under 150 psi, usually in the

range of 50 to 100 psi, while non-grave areas

exhibit compaction that is almost always over 150

PSI, typically 160 to 180 psi (Trinkley and Hacker

1997a, 1997b, 1998; Trinkley and Southerland

2007).

At the project site we had no known

graves to examine, but as we ran a north-south

line parallel to Dawson’s Circle, we identified five

possible graves. Each had compaction readings of

150 to 200 psi, while elsewhere we obtained

readings in excess of 250 to 300 psi. Compaction,

in fact, tended to increase as we moved eastward

into the area that had been cleared and grubbed.

Thus, it appears that the development property

has received considerable modification by

construction resulting in a significant degree of

compaction. This makes a penetrometer of limited

usefulness in the identification of graves.

As a consequence, Chicora Foundation

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

4

arranged for the firm of GEL Geophysics, LLC

from Charleston, SC to conduct a study using

ground penetrating radar (GPR).

The Lexington County Sheriff’s

Department released the remains they recovered

to Chicora and these are currently being examined

by Debi Hacker with Chicora Foundation for

metric and non-metric attributes.

5

HISTORICAL RESEARCH

Title Research

We have traced the title back to 1881 when

Levi Smith sold a 55 acre tract to David Drafts

(Lexington County Register of Deeds, DB CC, pg.

417). The property was described as “adjoining

lands of the said Levi Smith, George M.

Caughman and lands of the Rawl Old Place and is

bounded on the South side by the road leading

from Columbia to Augusta, three miles West of

Lexington Court House.” Drafts paid $220 for the

property ($4,150 in 2006$) .

Levi Smith was a white farmer born in

1804. He appears as early as the 1850 census when

he was already 46 years old. His wife, Elizabeth

(Wingard), was 39 years old and they had four

children, Samuel (17), Elizabeth (16), and May C.

(12). The census lists his occupation as farmer and

indicates that he had real estate valued at $1,000

($25,000 in 2006$), which appears to be slightly on

the low side, but still respectable. He does not

appear in the 1860 census, but is again shown in

the 1870 census, by that time 66 years old, but still

listed as a farmer. His real estate value had fallen

to $250 ($3,700 in 2006$), probably the result of the

Civil War. His personal estate was valued at $200

($3,000 in 2006$). Four children were listed as

living with Levi and Elizabeth: Mary C. (30), Sally

K. (27), Hannah L. (24), and Ellen R. (17). The 1880

census reveals that Levi, now 76, was still farming.

Also in the home were his wife, Elizabeth, and

their daughter, Sarah K. (the frequent change in

children’s names is probably just recordation

errors). Levi died in 1891, while his wife did not

die until 1902.

Thus, Levi was a small farmer toward the

end of his career when he sold property to David

Drafts. The transaction itself is not unusual; what

is more interesting is that Drafts was an African

American. The 1870 census shows David married

to Susan and having three daughters, Mary,

Herriet, and Jane. There were two sons at the time,

Edwin and Frank. Everyone listed for the family

was identified as a farm hand.

Both David and Susan were born slaves,

as were at least four of their five children. We

have identified a plantation owner in the 1860

slave schedule for Lexington County, Henry J.

Drafts, who ennumerates both a 30 year old male

and a 25 year old female slave – possibly David

and Susan. David Drafts 30 years in slavery makes

his acquisition of the Smith lands even more

remarkable.

By 1880 he is listed as Dave Drafts, a 50-

year old farmer born in South Carolina to parents

born in Virginia. The 1880 census reveals that he

was maried to Susie, who was 48 and was

“keeping house.” Both he and his wife were

illiterate – not unusual for rural African

Americans of that time period. Children included

Martha (26), Frank (18), and Jane (19). At the time

of the census in June, Susie was listed as being ill

with “fever,” possibly malaria. Frank was listed as

a farm laborer, probably meaning that he was

working on his father’s farm, while Jane was listed

as a laborer, possibly suggesting off-farm activity.

Also in the household were three grandchildren:

Aurelia (3), Augusta (5) and Jessie (3).

The next available census is that for 1900

(the 1890 census for South Carolina was

destroyed). David Drafts, by that time 70 years

old, was still listed as a farmer. Present in his

household were Lucy Kinard (a 65 year old

widow) listed as a boarder, Gracy Kinard (10), and

Gary Hampton (16). Confusing matters, David

Drafts is shown as being married for 8 years,

suggesting that perhaps he was now married to

Lucy Kinard.

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

6

Frank Drafts is shown as having

established his own household, being married to

Lilla, for the past 16 years. Children included

Belton (9), Drilton (6), and Lessus (5). Also in the

household was his daughter, Berley Caughman

(16), who had married Green Caughman (22). At

the time of the census Berley had just two weeks

prior given birth to their first child (still

unnamed). Unfortunately both Frank Drafts and

Green Caughman can not be found in the 1910 or

1920 census.

Sometime prior to 1905 David Drafts died

intestate (since no will can be found in Lexington

County). His proprety went through a lengthy

process of division between his heirs, resulting in

the survey of the parcel (the plat was not recorded

and is assumed lost) and the division of the 55

acres into seven parcels (which are discussed

below in parcel order).

Tra ct 1 was apparently given to Frank H.

Drafts since in 1929 he sold it to the Home

National Bank of Lexington, SC for $100. The

property description reveals that, like all of the

other parcels, it contained 8¾ acres and fronted

on US Highway No. 1. To the east were the Rawl

estate lands and to the west was property of

Martha Walker (Lexington County Register of

Deeds, DB 4L, pg. 420).

Tract 2 was deeded by Frank H. Drafts,

Edward Drafts, Jane Walker, and Susie Sheppard,

“heirs of the estate of David Drafts” to Martha

Walker on August 6, 1910 (Lexington County

Register of Deeds, DB 3O, pg. 264). The location is

bounded to the east by “Tract No. 1 in like manner

conveyed to F.H. Drafts,” and to the west by

“Tract No. 3 in like manner conveyed to Ellen

Crapps, Green Cartman and Peroilla [sic] Gardner

children of Harriet Cartman, Deceased.”

Tract 3 was given to Percilla Gardner,

Ellen Crappe, and Green Cortman by F.H. Drafts,

Martha Walker, Edward Drafts, Jane Walker, and

Susie Sheppard. To the east was Tract 2 and to the

west were “the heirs of Amelia Robertson, viz.

Jesse Johnson, Melvin Anderson, Jane Anderson,

Mary Anderson, Viola Robertson, Susie

Robertson, and David Robertson (Lexington

County Register of Deeds, DB 3Q, pg. 573).

Tract 4 was deeded on August 6, 1910 by

F.H. Drafts, Martha Walker, Edward Drafts, June

Walker, and Susie Sheppard to Jessie Johnson,

Melvin Anderson, Jane Anderson, Mary

Anderson, Viola Robertson, Susie Robertson, and

David Robertson, “children of Amelia Robertson,

deceased” (Lexington County Register of Deeds,

DB 3L, pg.10). To the west was Tract 5, conveyed

to Edward Drafts.

While Tract 5 is known to have been

conveyed to Edward Drafts, the deed has not

been identified in this research. Nevertheless, we

know that on January 3, 1905 Edward Drafts

obtained a loan of $14.59 at 8% interest from D.E.

Ballentine, using his 1/7 interest in the David

Drafts estate as collaterial (Lexington County

Mortgage Book V, pg. 115). The following year, on

August 7, he obtained a second loan for $25 from

the firm of Graham and Sturkie using the same

tract again as collaterial. While the purpose is not

stated, they were likely living and planting loans,

typical of the period as small farmers or tenants

attempted to survive from year to year. However,

by 1911 neither loan had been repaid and

Ballentine filed suit for the recovery of his monies

(with Graham and Sturkie joining with him). The

matter came before the Lexington County Circuit

Court in 1911 (Case 2458) and the property was

ordered sold.

Tract 5 was then sold in May 1911 by the

Lexington County Sheriff to Frank Drafts for $112

(Lexington County Register of Deeds, DB 3B, pg.

340). Frank Drafts held the tract until 1914 when

he sold it for $150 to S.R. Drafts (Lexington

County Register of Deeds, DB 3Q, pg. 168).

Tract 6 was conveyed by Frank Drafts,

Mathra Walker, Edmund Drafts, and Jane Walker

to Louisa Fields, Susie Sheppard, Carry Gardner,

Julius Deshade, and Sammy Deshade (Lexington

County Register of Deeds 3H, pg. 90).

HISTORICAL RESEARCH

7

The final parcel, Tract 7, was sold on

August 6, 1910 by Frank Drafts, Martha Walker,

Edward Drafts, and Susie Sheppard to Jane

Walker (Lexington County Register of Deeds, DB

3H, pg. 54). To the west of this final tract was the

property of W.P. Roof.

The division of the 55 acres into seven 8¾

acre parcels is typical of heirs property divisions.

What might have been a profitable subsistence

farm, through repeated divisions, becomes so

small that it can no longer be profitably farmed.

This may have happened with David Drafts’

estate. Of course, it is possible for families to band

together and operate communally, although

experience suggests that even this strains

resources. Unfortunately we have no agricultural

census records from that time period to help us

understand how the property might have been

used.

The ultimate fate of the seven parcels was

not researched since only two are of concern to

this project.

The property next appears in 1927 when

Tract 3 was sold to Andrew Gates by Green

Cortman, Ellen Trapp, and Siller Gardner for $170

($1,980 in 2006$) (Lexington County Register of

Deeds, DB 4Y, pg. 200). The deed reveals that the

property had been inherited by their mother,

Harriet Cortman from her father, David Drafts.

Harriet Cortman is found in 1880 census,

married to Green Cortman and enumerated in the

Boiling Springs Township of Lexington County.

She was 22 years old and her husband was 29.

Both are listed as “domestic laborer” and they

have three children: Sharlot (9), Elen (4), and

Green A. (1).

The property was described as “being on

the Jefferson Davis National Highway, about three

miles west of the County [sic] of Lexington . . .

containing eight and three-fourth (8¾) acres, more

or less, and bounded on the north by lands of

Martha Walker; on the east by Jefferson Davis

Highway; on the south by lot of Sim Drafts, and

on the west by lands of the Estate of D.B. Rawl,

desceased.”

The deed, however, specifies that the

sellers, “reserve the cemetery situated on said tract

of land and the right of egress and ingress to said

cemetery, the lines of said cemetery to be agreed

upon and established by the parties to this deed

and when the said lines

have been established they

shall remain as the

permanent lines and

boundaries of said

cemetery, provided the

total area of said cemetery

plot shall not exceed one

quarter of an acre.” While

not specified, it seems

likely that the reserved

cemetery was that of the

Drafts family and would

have been in use for

perhaps 46 years by this

time.

N.B.T. of Columbia, Inc.

↑ 2006

Sonja H. Shull et al

↑ 2001, 2005

Kenneth E. and Seth M. Hendrix

↑ 1953

Vera E. Hendrix

↑ 1936 ↑ 1939 (via tax sale)

Andrew Gates Martha Walker

↑ 1927 ↑ (inheritance)

Green Cortman, Ellen Trapp, Siller Gardner

↑ (inheritance)

Harriet Cortman

↑ (inheritance)

Tract 3 Tract 2

David Drafts

↑ 1881

Levi Smith

Figure 3. Graphic representation of the property title search.

Andrew Gates is

found in the 1920 census as

a 26 year old black farmer

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

8

Figure 4. Plat of the study tract from 1974 (Lexington County Register of Deeds, PB G, pg. 137).

HISTORICAL RESEARCH

9

Figure 5. Plat of the study tract from 2006 (United Design Services, Inc.).

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

10

who was renting his residence (and probably his

farm land) in the Hollow Creek township.

His family consisted only of his wife, Georgie, and

their 10 year old adopted daughter, Ella Summers.

Gates held the property until 1936 when

he sold it for $175 to Vera E. Hendrix (Lexington

County Register of Deeds, DB 4Z, pg. 198). No

mention was made of the cemetery. For the first

time since the property was sold in 1881 the tract

left black ownership. Vera Hendrix was the wife

of Lexington farmer, Wilber B. Hendrix. Two sons,

Kenneth (12) and Seth (10) are listed in the 1930

census.

In 1953 Vera E.Hendrix sold the tract to

her sons, Kenneth E. and Seth M. Hendrix for $5

and love and affection, maintaining a life estate

(Lexington County Register of Deeds,

DB 7N, pg. 268).

This deed also included a

second 8¾ parcel described as

bounded “North by lands of Clyde

Hendrix; East by lands of Hoyt Weed;

South by Highway No. 1 and on the

West by Mrs. Vera Hendrix.”

Hendrix had obtained this

parcel from the Lexington County

Sheriff as a result of the property,

owned by Martha Walker (Tract 2),

being auctioned for taxes in 1939

(Lexington County Register of Deeds,

DB 4R, pg. 62). The 8¾ acres was

acquired for only $33.35 (taxes of

$28.29 and interest of $5.05).

The only Martha Walker we

have been able to identify is a 60 year

old African American widow listed in

the 1910 census from Lexington

township. She is listed on the same

census page as Frank Drafts and his

father, David Drafts, so it is likely the owner of the

adjacent property. Her occupation was listed as

farm laborer, along with her 40 year old widowed

daughter, Jessa. Children living in the household

included Chris (19), working at a sawmill; Ada

(12); Cora (7); Neddie (4); and Annie M. (2).

Vera Hendrix died intestate in 1965

(Lexington County Probate Court Bk 813, pg. 122)

and the property passed to her sons. From

Kenneth and Seth Hendrix the property passed to

their children and, in 2006, the parcel, described as

16.58 acres, was sold to N.B.T. of Columbia, Inc.

for $746,100 ( Lexington County Register of Deeds,

DB R11023, pg. 209).

Thus, the study parcel is composed of two

of the seven Drafts tracts (Nos. 2 and 3). The

cemetery reservation is listed for Tract 3, which

would have been the western half of the existing

study tract. Although this does not precisely

define the cemetery location, it does provide clear

evidence of its existence and does limit the search

area.

Figure 6. Portion of the 1946 Gilbert 15’ topographic map.

HISTORICAL RESEARCH

11

Identified Plats and Maps

Only two plats have been identified of the

study tract. While a plat of the property division

was prepared by Luther L. Lown [?], it was not

recorded with any of the deeds. Probably retained

by a family member, most likely Frank Drafts, it is

likely lost.

The first plat dates from 1974 and is

associated with the property’s ownership by

Kenneth E. and Seth M. Hendrix (Figure 4) . This

shows the 16.8 acre parcel bounded by US 1 to the

south, Oscar Hendrix to the west, Clyde Hendrix

to the north, and Henry E. Harmon to the east. No

other features are identified on the plat.

The second plat, from the sale of the

property to N.B.T. of Columbia, Inc., provides

more detail. US 1 (Augusta Road) bounds the tract

to the south; to the west are lots of Henry

Anderson, Novella Derrick, Walter Anderson, and

Juanita Hendrix. Also running along the west side,

just beyond the property line, is a road identified

as Cay Lane (shown as Coy Lane on other maps).

To the north is property of Old Woodlands

Development Corp. To the east is property still

identified as belonging to Henry E. Harmon

(Figure 5). The more recent survey identifies the

property as 16.58 acres. Other than wetlands and

the 100-year flood line, shown at the north end of

the parcel, no other features are shown.

Other readily available maps, such as the

1922 USDA Soil Survey map

of Lexington County and the

1946 Gilbert 15’ topographic

map, fail to identify any

cemetery on the property.

The 1922 soil survey may

document a structure on the

interior of the property –

very possibly one of the

structures along the western

edge – the later 1946

topographic map shows

only structures along

Augusta Highway (Figure

6).

The failure to

identify African American

graveyards on maps of this

period, however, is not

unusual. In general, black

graveyards were ignored

until the second half of the

twentieth century when

USGS and USDA personnel

began to more regularly identify their locations

during surveys. The graveyards, however, had to

be visible – and identifiable – to the surveyors, so

even then many were likely missed.

Figure 7. 1943 aerial photograph of the project area.

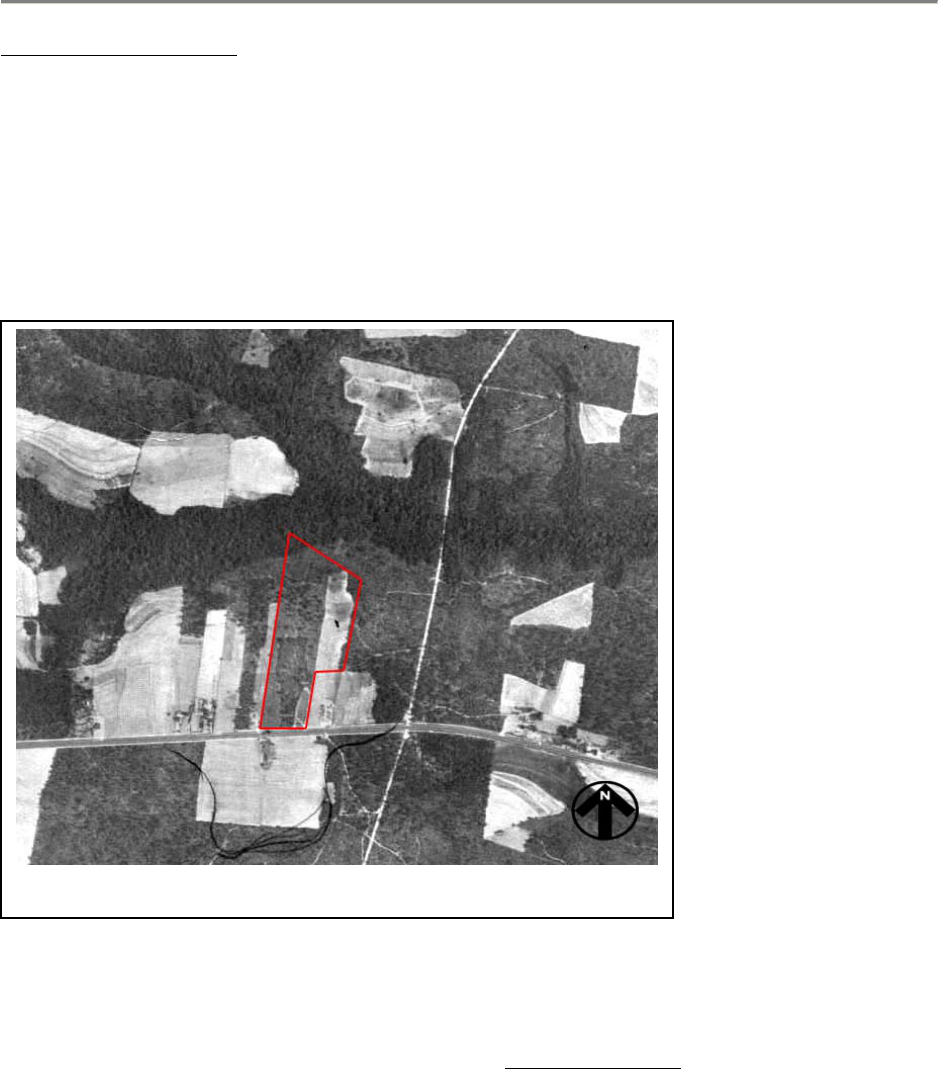

Aerial Photographs

The earliest aerial photography of the

project area is the Agricultural Stabilization and

Conser-vation Service (ASCS) images from 1938.

These, however, are not immediately available.

The next images are those from 1943 and they

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

12

clearly show the project area (Figure 7). All seven

tracts of the Drafts estate

are identifiable in the

image. By 1943 only a

third of Tract 1 was

under cultivation, all of

Tract 2 was farmed,

Tract 3 was entirely

wooded, about half of

Tract 4 was cultivated,

and substantial portions

of Tracts 5-7 were being

cultivated. Of special

interest, however, is

Tract 3 where the

cemetery has been

identified from deed

research. The imagery

reveals that a central

field was in different

timber (probably pine)

than the remainder of

the parcel. This old field

takes the shape of an

upside-down bottle of

darker vegetation

surrounded by lighter (and

probably hardwood) trees.

This suggests that the

cemetery was located at

the edge of the field and a

probable location is

between the road

separating Tracts 3 and 4

and the old field (although

the cemetery cannot be

identified on the aerial

photograph.

Figure 8. 1959 aerial photograph of the project area.

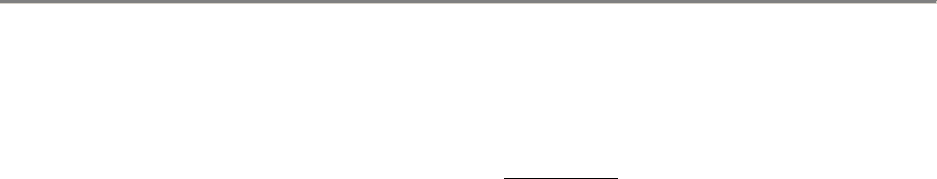

The next image

available to us is the 1959

ASCS photography (Figure

8). The old field is barely

visible, although there

does appear to be road

cutting across the middle

of the two parcels.

Otherwise the only

substantial difference is

Figure 9. 1966 aerial photograph of the project area.

HISTORICAL RESEARCH

13

that Tract 4 has been placed under more intensive

cultivation.

In 1966 we see that Tract 3, previously

heavily wooded, appears to have been logged. The

road cutting across the two parcels is still clearly

visible and immediately north of this road,

adjacent to the Tract 4 property line there is an

area of darker vegetation which may represent an

area avoided by logging. This may represent the

graveyard although it is not especially convincing.

The 1977 aerial (Figure 10) shows

relatively little change in the properties, although

the darker vegetation on the property line

between Tracts 3 and 4 is still visible. The quality

of the images, intended for tracking argicultural

land use, is not sufficient to allow a more

definitive interpretation.

The 1981 aerials are no longer at a scale of

1:20,000, but were taken at a scale of 1:40,000,

dramatically reducing their usefulness for this sort

of research. The modern aerials, dating from 2006,

fail to identify any

distinctive vegetation.

They do, however,

reveal that the project

area had only become

more densely wooded

since 1970 – otherwise

there appear to be no

changes. While the

road cutting through

the property is no

longer visible (being

obscured by tree

cover), its remnants

were visible on Tract 2.

The clearing and

grubbing for

development, how-

ever, has removed any

visible evidence of this

road that might be

used to approximate

the location of the

darker vegetation

found on the 1966 and 1977 images.

Fi

g

ure 10. 1977 aerial

p

hoto

g

ra

p

h of the

p

ro

j

ect area.

Documented Burials

The typical approach used for identifying

a cemetery and then researching those buried

there involves using existing stones to research

death certificates (available after 1914). If

certificates can be found, they typically identify

the place of burial. Once the cemetery name is

known, it is possible to scan death certificates

looking for that specific name.

This process, however, was not possible at

the Drafts graveyard since there were no marked

burials. We were initially told by the sheriff’s

department that the cemetery name was reported

to be Rawls. A day was spent searching for that

name without success.

Unable to make any headway using this

approach we began by attempting to identify

death certificates for individuals which might

reasonably be buried in the graveyard, given their

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

14

association with the property. We identified that

Frank Draft (1872-1933) and his wife Lillie Draft

(1880-1939) were buried at Strothers and Rawl

respectively. With no certainity that either name is

necessarily correct for the graveyard on the study

tract, we began scanning death certificates and

identified 14 additional individuals associated

with Strother (or some variation) . No additional

burials were found attributed to Rawl. The

identified individuals are shown in Table 1.

We do have two members of the Drafts

family included. The 1910 census identifies Lillie

Drafts as the wife of Sim Drafts, a farmer renting

his land in the Hollow Creek area.

Rawl, of course, is associated with an

estate from which the Drafts property was carved

by Levy Smith and we know that Tract 1 was

described as west of the Rawl

lands. Since the 1880 census

reveals a large number of

both black and white Rawls

in the immediate area, it is

entirely plausible that Rawls

might be included.

Similarly, we found

several African American

Strothers living on US 1 or

Hendrix Road in the 1930

census – so this family may

have chosen to use the

cemetery begun by the Drafts.

Lessie B. Wise was

identified in the 1930 census

as the daughter of Callie and

Lucy Wise, farm laborers who

lived on US Highway 1, and

who rented their house for $2

a month. Ervin Summers was

found in the 1910 census as a

farmer living on Ferry Road

(probably nearby Wise Ferry

Road) who rented his farm.

Ilena Richardson is found in

the 1920 census as the wife of

Mac Richardson, who was

renting a farm in the Lexington area. Richard

Norris, found in the 1910 census, was a single man

renting his home and farming. This may be the

same individual who, by 1920, was listed as a

servant in the William Quick family living on

Main Street in Lexington. Orange Izeral was the

young son of Abraham Isreal according to the

1930 census. Abraham was a farm laborer, living

on Midway Road in Lexington. Mary Corley may

be the wife of Henry Corley, who in 1930 is

identified as working for the public works

department and living in Lexington.

Figure 11. 2006 aerial photograph of the project area showing contours

and lot lines (from the Lexington County GIS).

This diverse range of individuals is not

unexpected at a traditional, rural, African

American cemetery that would have been used by

the community. Nevertheless, with the available

information it is difficult to convincingly argue

HISTORICAL RESEARCH

15

that the graveyard on the study parcel is either the

Rawl or Strother cemetery identified from death

certificates.

Reported Burials

Distinct from burials

documented by death

certificates, there are a

number of reported burials.

The list shown as Table 2 was

provided by the Lexington

County Coroner and we

believe it was provided by

individuals claiming ancestry

to those buried in the

graveyard. While oral history

is a powerful and important

tool, we believe that it

requires confirmation and lists

such as this are difficult to

confirm. Absent death

certificates, period obituaries,

recordation in family

Bibles, or similar official

or period

documentation, it is

virtually impossible to

prove a particular

individual is buried in a

graveyard. Never-

theless, it is often

possible to show

sufficient evidence, such

as ownership, family

connections, or

neighborhood connects,

to make burial in a

particular cemetery

likely. This is the case

for many of the

individuals identified in

Table 2.

The Drafts and

Walkers are both known

to have been African

American families

owning the property – so their names are entirely

plausible. The Anderson’s own adjacent property

which may have derived from the Rawls estate

referenced in several of the previous deeds – and

Table 1.

Burials Identified in the Rawl or Strother Cemetery from Death Certificates

Name Certificate Birth Death Cemetery

Blackwell, Charlie 19078 1870 5/29/1935 Strathers

Brown, Mattie 9825 1870 6/16/1940 Strothers

Corley, Mary 2258 1906 1/31/1932 Strother

Drafts, Frank 18288 1872 11/1/1933 Strothers

Drafts, Lillie B. 10176 1880 5/1/1939 Rawl

Hall, John Henry 8209 1907 5/11/1940 Strothers

Iseral, Orange 9433 1923 6/5/1935 Strathers

Jackson, Henry 14608 1887 9/4/1940 Strothers

Keisler, Mary A. 19516 1938 12/21/1940 Strothers

Norris, Richard 16205 1858 8/8/1921 Strothers

Parker, Edith 8207 1903 4/21/1940 Strather

Rawl, Martha A. 4351 1911 3/6/1935 Strathers

Rawl, Rose Ella 10105 1932 6/8/1933 Strothers

Richardson, Ilena 18012 1896 12/22/1939 Strather

Richardson, Joe 19314 1902 11/27/1940 Strothers

Strother, James 18010 1939 12/5/1939 Strother

Strother, Lula 13688 1880 7/6/1920 Strother

Strother, Sarah Pearl 6016 1941 5/9/1942 Strother

Strother, Willie C. 11511 1917 5/14/1918 Strother

Summers, Ervin 2312 1863 2/10/1942 Strothers

Wise, Lessie B. 12283 1915 8/4/1935 Strathers

Wise, Monroe 10175 1896

7

/

17

/

1939

Strother

Table 2.

Individuals Reported to be Buried on the Property

Anderson, Av___ R.

Drafts, Davis & Susie

Drafts, Edwin & Lavinia

Drafts, Frank & Lil

Drafts, Fred

Drafts, Mary

Holmes, Abraham & Lisa Ann

Holmes, Ada

Holmes, Augustina

Holmes, Jacob Sr.

Holmes, Joseph

Holmes, Meshach

Holmes, Shad

Holmes, Thurmond

Jones, Carolina

Jones, Charlie

Jones, Ida

Jones, Minnia

Jones, Morris

Jones, Nino

Jones, William & Florence

Kinard, Jessie Holmes

Perry, Jane Draft

Walker, Allen & Mary

Walker, Elder A.

Walker, John H.

Walker, Magaline

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

16

at least one Anderson is shown on the list of

expected burials. The relationship of the Holmes,

Jones, and Perry families is not immediately clear.

The one Perry burial was obviously a Drafts who

maried a Perry.

In an effort to better understand those

reported to be buried in the graveyard, each name

was searched for in census records between 1870

and 1930 (not including 1890, which no longer

exists for South Carolina).

Not surprisingly, most of the names could

not be identified. This may be the result of

transcription errors in the list, individuals going

by several names, or family inaccuracies.

Nevertheless, several names were identified and

these help us better understand the possible use of

the graveyard.

Drafts

The reference to Davis Drafts is likely

David or Dave Draft, whose wife was Susie or

Susan. He has been previously discussed and was

the first owner of the parcel on which a

reservation for the cemetery was later made.

Edward Drafts is found as a 20 year old

black farm laborer on the 1880 census. He is

shown as maried to Levinie (not Lavinia), listed as

18 and a laborer. Both were shown as illiterate and

having a 1-year old child, Ella.

Brief mention has also been made of Frank

Drafts – a son of David Drafts identified in the

1900 census as maried to Lilian (not significantly

different from the shortened version, Lil, shown

in Table 1).

Fred and Mary Drafts have not been

identified, so their relationship to the remainder of

the family cannot be identified through these

records.

Holmes

Abraham Holmes and his wife Sila Ann

(not Lisa Ann as reported in Table 1) are found in

the 1900 census. Abraham was shown as a 51 year

old farmer, married 11 years to Sila Ann, 36 years

old. He was listed as a farmer who was able to

read and write. His wife, listed as a house keeper

was not literate. Also in the household were four

children: David (19), Izzie (11), Jacob (8), and

Nathaniel (6). David, a farm laborer, was unable to

read or write, while his younger sister, Izzie, had

apparently been able to attend school and was

shown as literate.

Abraham is again shown on the 1910

census, living on Georges Mill Road. By this time

he was a widower, living with two children,

David and Nathan. In 1910, however, Abraham

was shown as a cotton mill laborer, as was 18 year

old Nathan. Only David was still tied to the land

as a farm laborer.

Joseph Holmes is likely the child of

Thearon Holmes, listed in the 1900 census (see the

Kinard family, below).

Surprisingly, we were unable to positively

identify any of the other Holmeses listed in Table

1. We did find a 75 year old Jacob Holmes, Sr. in

1880, although the listing was for Charleston.

Abraham also had a child, Jacob; but we have not

been able to identify this individual as an adult.

Jones

We have identified William and Floris

Jones in the 1930 census. William was a 60 year

old individual living on a farm and paying

$6/month rental for his house. He was also

working at a turpentine distillery. His wife, Floris,

was 50 years old. Also living in the house were

five of their children, including Odell (20), L.F.

(19), Ethel L. (18), J.H. (7), and Robert D. (3). Odell

and L.F. both worked at a saw mill. Also in the

home was Ibabelle Strother, listed as a 14 year old

granddaughter.

This is likely the same William Jones

found in the 1910 census, married to Florence

Jones. At that time William was a farmer; his wife

HISTORICAL RESEARCH

17

and several older children were listed as farm

labor for the home farm. The children at that time

were Bell (16), Elvin (14), Doll (10), Eva (8), Emry

(6), Led (5), and Mook (3) . Florence is listed as

having given birth to 11 children, 9 of whom were

still living (indicating that two had already moved

away from home or had died).

No other Jones were identified in the

census records.

Kinard

The one Kinard identified is Jessie Holmes

Kinard, indicating intermarriage with the Homes

family. A Jessie Kinard was found in the 1900

census, identified as a 21 year old widow living

with her parents, Arthur and Martha Walker. Also

in the household their other children, Morijay (15),

Clisby (18), and Thearon Holmes (25). Thearon is

listed as single, although it appears that she had

been maried to a Holmes and had given birth to

five children, four of whom were still alive: John

B. (10), Mattie E. (6), Joseph (3), and Bulah (5) – all

listed as the granddaughters and grandsons of

Arthur and Martha Walker. Jessie Kinard had two

children: Christopher (6) and Edward (2) – they,

too, were listed as the grandsons of Arthur and

Martha Walker.

This family, more clearly than any of the

others, reveals the complex interconnections

between – at the very least – the Holmes and

Walker families.

Walker

Allen and Mary Walker were identified in

the 1880 census. He was a 37 year old farm laborer

and Mary E. was his 24 year old wife, whose

occupation was listed as “keeping house.” Both

were identified as illiterate. His association with

the property appears to be through his wife’s

family since the census reveals that also living in

his household was Hariett Rawls, listed as

“Mother.” Children included Lucinda (7), Mattie

(4), Magdaline (3), and J. Henry (2). Two of these

children – John H. and Magaline [sic] – are

reported to be buried in the graveyard.

The only Walker not immediately

identified is Elder A.

Oral History

Oral history can be a valuable tool in

cemetery research, although memories fade and

locations change dramatically with time.

Moreover, memories can be modified through

group suggestion or leading questions. We need

only to look at the controversy surrounding

eyewitness testimony in court cases to fully

apprecicate the wide range of opinion (see, for

example, Ebbesen and Konecni 1997).

While it is critical that oral history be

independently confirmed and buttressed, it is

always a mistake to discount the reports and

memories of the local community.

In this particular case, it is possible that

individuals have recollections of the cemetery

location or size. It might also be possible for

relatives and descendants to unravel the

complexity of the various families. Or they may

have memories of what the cemetery was called.

Unfortunately, in spite of several calls and

requests for interviews, our calls were not

returned. In addition, the interviews and data

collected by the Lexington County Sheriff’s

Department was not available at this time of this

report.

As a consequence, we attempted to gather

together reports made in the media, as well as

items relayed to us by both the offices of the

Lexington County Coroner and Lexington County

Sheriff. These are reported for the record; while

we have made ocassional, parenthetical

comments, none of the reports can be

independently varied by us at this time.

o Reports of the number of burials range

from 32 to 100. We have no good means

of estimating the number of individuals.

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

18

A quarter acre could hold upwards of 150

bodies. Traditional African American

cemetery densities can exceed or be below

that number. These graveyards, however,

often have poorly defined boundaries, so

limits are frequently difficult to establish.

o The cemetery is reported to have begun

at a fence along the western property

edge and extended eastward for an

indeterminate distance. This is consistent

with our observations of the aerial

photographs, showing darker vegetation

at the western edge of the property.

o Revious Amaker reported that she knew

of the cemetery. She also reported that a

previous owner of the property was told

to be aware of the cemetery.

o Walter Anderson reported that his great-

grandmother or great-great-grandmother

(on his mother’s side) is buried in the

graveyard (reported accounts differ). Our

research has identified at least five

different Andersons: Melvin, Jane, Mary,

Henry, and Walter. This claim is entirely

plausible.

o One report claims that family members

lost the land 70 years ago because of

unpaid taxes. While the historic research

does indicate that Edward Drafts lost his

share of the property for defaulting on

loans, the tract was purchased by another

family member. Martha Walker, the

owner of Tract 2, did lose her property for

unpaid taxes in 1939. However, we have

found no evidence that the parcel on

which the cemetery is located, Tract 3,

was ever lost – it was sold by family

members to a third party.

o One individual claimed that graves were

tended into the late 1950s, at which time

the owners prevented further access. The

owners at that time would have been

Kenneth E. and Seth M. Hendrix.We have

not, however, spoken with any Hendrix

relatives.

19

CONCLUSIONS

The historical research reveals that in 1881

an elderly white farmer, Levi Smith, sold David

Drafts, a freedman living in the Lexington area, a

55 acre parcel. It is likely that Drafts farmed the

land and raised a large family. Upon his death

between 1900 and 1905, his property was equally

divided among his heirs. For reasons that are not

entirely clear, this process was not completed until

around 1911 when the property was divided into

seven equal tracts, each identified as 8¾ acres

(this indicates that the Levi Smith property must

have actually been just over 61 acres – an error not

uncommon for the period).

These tracts were numbered from west to

east and it seems likely that the relatively

profitable albeit small Drafts farm was reduced to

the status of marginal cultivation. Nevertheless,

various decendants, represented by the family

names Anderson, Cortman (or Cartman), Crapps

(or Crappe, Trappe), Deshade, Drafts, Fields,

Gardner, Johnson, Robertson, Sheppard, and

Walker continued to live on various tracts. It

seems probable that these family names represent

the core of those individuals buried in the

cemetery.

The study tract includes two of these

parcels, numbered Tracts 2 and 3, that had been

acquired by Vera Hendrix and passed through her

children, eventually being purchased by N.B.T. of

Columbia for development.

However, one of the deeds, transferring

the property from the heirs of Harriet Cortman to

Andrew Gates in 1927, specifically reserved a

cemetery. The size was not specifically identified,

although by that date the individuals most

familiar with the property did not expect it to be

greater than ¼ acre. The cemetery boundaries

were to be determined and agreed upon between

the Cortmans and Gates, but there is no evidence

that this occurred (for example, no plat was filed

showing the cemetery). The ¼ acre, however,

should be considered the minimal size of the

cemetery, accepting the potential that it may have

continued to grow. In addition it would be

inappropriate to assume that this ¼ acre could be

simply platted as a square or rectangle. African

American cemeteries are often amorphous.

The next time the property was conveyed,

when Gates sold the parcel to Hendrix in 1936 –

nine years later – there was no mention made of

the cemetery. Occuring over 70 years ago, it is

impossible to know the reason for this; it certainly

seems implausible that in only nine years Gates

would completely forget about the cemetery.

Regardless, the last legal mention of the cemetery

we have identified is the 1927 deed.

This work has resulted in the compolation

of a kinship or lineage chart for the drafts family

that, while certainly not complete, begins to assist

in better understanding the relationships of at

least some individuals thought to be buried in the

graveyard.

In addition to the family names identified

as descendants of David Drafts, we have also

identified a series of names that may be associated

with the cemetery, based on limited evidence of

the cemetery name. These include Blackwell,

Corley, Isreal, Norris, Rawl, Richardson, Strother,

Summers, and Wise. While these names cannot –

at this time – be definitively linked to the

cemetery, representatives did live in the

immediate area. It would not be uncommon or

unheard of for poor, African American tenant

farmers to use a nearby cemetery for the burial of

their family members.

Still in progress at the time of this research

is an effort to identify additional graves using

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

20

Figure 12. Lineage chart based on title research and examination of Federal census records.

CONCLUSIONS

21

ground penetrating radar, analysis of the existing

remains, and an effort to recover more the missing

portions of the two skeletons previously recovered

by Lexington County. Efforts will continue to

make contact with posited family members and

solicit their input, although such efforts thus far

have not been successful.

HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON DRAFTS GRAVEYARD, LEXINGTON COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA

22

23

SOURCES CITED

Ebbe B. Ebbesen and Vladimir J. Konecni

1997 Eyewitness Memory Research:

Probative v. Prejudicial Value.

Expert Evidence: The International

Digest of Human Behavior, Science,

and the Law 5:2-28.

Trinkley, Michael and Debi Hacker

1997a Additional Boundary Research at the

Kings Cemetery (38CH1590),

Charleston County, South Carolina.

Research Contribution 214.

Chicora Foundation, Inc.,

Columbia.

1997b Grave Inventory and Preservation

Recommendations for the Maple

Grove United Methodist Church

Cemetery, Haywood County, North

Carolina. Research Contribution

230. Chicora Foundation, Inc.,

Columbia.

1998 Grave Inventory and Preservation

Recommendations for the Walker

Family Cemetery, Greenville

County, South Carolina. Research

Series 248. Chicora Foundation,

Inc., Columbia.

Trinkley, Michael and Nicole Southerland

2007 Penetrometer Survey of the Nance

Property – Moss Family Cemetery,

Stanly County, North Carolina.

Research Contribution 464.

Chicora Foundation, Inc.,

Columbia.

Other Sources:

Ancestry.com

SCDHEC death certificate index

1850 slave schedule, Lexington Co.

1860 slave schedule, Lexington Co.

1860 population census, Lexington Co.

1870 population census, Lexington Co.

1880 population census, Lexington Co.

1900 population census, Lexington Co.

1910 population census, Lexington Co.

1920 population census, Lexington Co.

1930 population census, Lexington Co.

Lexington County Clerk of Court

Court of Common Pleas Cases

Lexington County Probate Court

Index of Estates

Lexington County Register of Deeds

Grantor/Grantee Indexes

Deed Books

Plat Book Index

Plat Books

South Carolina Department of Archives and

History

Death Certificates

University of South Carolina Map Repository

Aerial photographs, Lexington County

USGS topographic maps, Lexington

County

USDA, Soil Conservation Service, Soil

Survey Map, Lexington County

CULTURAL RESOURCES SURVEY OF A 17 ACRE TRACT IN MARION

24

Archaeological

Investigations

Historical Research

Preservation

Education

Interpretation

Heritage Marketing

Museum Support

Programs

Chicora Foundation, Inc.

PO Box 8664 ▪ 861 Arbutus Drive

Columbia, SC 29202-8664

Tel: 803-787-6910

Fax: 803-787-6910

www.chicora.org