GitHub for Developers

Training Manual

-v1.0

Table of Contents

Welcome to GitHub for Developers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê1

License. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê1

Getting Ready for Class . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê2

Step 1: Set Up Your GitHub.com Account . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê2

Step 2: Install Git. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê2

Step 3: Set Up Your Text Editor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê3

Exploring . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê4

Getting Started With Collaboration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê5

What is GitHub? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê5

What is Git? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê6

Exploring a GitHub Repository . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê8

Using GitHub Issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê9

Activity: Creating A GitHub Issue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê10

Using Markdown. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê10

Understanding the GitHub Flow. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê12

The Essential GitHub Workflow . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê12

Branching with Git . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê13

Branching Defined . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê13

Activity: Creating A Branch with GitHub . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê13

Local Git Configuration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê15

Checking Your Git Version. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê15

Git Configuration Levels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê15

Viewing Your Configurations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê16

Configuring Your User Name and Email . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê16

Configuring a Default Text Editor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê17

Configuring autocrlf . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê17

Configuring Default Push Behavior . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê17

Working Locally with Git . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê19

Creating a Local Copy of the repo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê19

Our Favorite Git command: git status. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê20

Using Branches locally. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê20

Switching Branches . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê20

Activity: Creating a New File . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê21

The Two Stage Commit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê21

Collaborating on Your Code . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê24

Pushing Your Changes to GitHub . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê24

Activity: Creating a Pull Request. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê25

Exploring a Pull Request . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê25

Exploring . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê26

Editing Files on GitHub . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê28

Editing a File on GitHub . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê28

Committing Changes on GitHub . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê28

Merging Pull Requests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê29

Merge Explained . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê29

Merging Your Pull Request . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê30

Cleaning Up Your Branches. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê30

Viewing Local Changes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê32

Different Commands for Viewing Changes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê32

Viewing Local Project History . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê33

Using Git Log. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê33

Fixing Commit Mistakes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê34

Changing Commits. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê34

Streamlining Your Workflow with Aliases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê35

Creating Custom Aliases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê35

Workflow Review Project: GitHub Games . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê36

User Accounts vs. Organization Accounts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê36

What is a Fork? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê36

Creating a Fork . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê36

Introduction to GitHub Pages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê37

Workflow Review: Updating the README.md . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê37

Reverting Commits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê38

How Commits Are Made . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê38

Safe Operations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê39

Reverting Commits with git revert . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê39

Resolving Merge Conflicts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê41

Local Merge Conflicts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê41

Remote Merge Conflicts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê42

Exploring . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê42

Helpful Git Commands . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê43

Moving and Renaming Files with Git . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê43

Staging Hunks of Changes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê43

Rewriting History with Git Reset . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê44

Understanding Reset . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê44

Reset Modes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê45

Creating a Local Repository . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê46

Reset Soft . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê46

Reset Mixed . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê47

Reset Hard. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê48

Does Gone Really Mean Gone? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê49

Exploring . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê49

Cherry Picking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê50

You Just Want That One Commit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê50

Merge Strategies: Rebase . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê51

About Git rebase . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê51

Activity: Git Rebase Practice . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê52

Appendix A: Talking About Workflows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê53

Discussion Guide: Team Workflows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ê53

Welcome to GitHub for Developers

Today you will embark on an exciting new adventure: learning how to use

Git and GitHub.

As we move through today’s materials, please keep in mind: this class is

for you! Be sure to follow along, try the activities, and ask lots of

questions!

License

The prose, course text, slide layouts, class outlines, diagrams, HTML, CSS,

and Markdown code in the set of educational materials located in this

repository are licensed as CC BY 4.0. The Octocat, GitHub logo and other

already-copyrighted and already-reserved trademarks and images are not

covered by this license.

For more information, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

License | 1

Getting Ready for Class

While you are waiting for class to begin, please take a few minutes to set

up your local work environment.

Step 1: Set Up Your GitHub.com Account

For this class, we will use a public account on GitHub.com. We do this for

a few reasons:

• We don’t want you to "practice" in repositories that contain real code.

• We are going to break some things so we can teach you how to fix

them. (therefore, refer to #1 above)

If you already have a github.com account you can skip this step.

Otherwise, you can set up your free account by following these steps:

1. Access GitHub.com and click Sign up.

2. Choose the free account.

3. You will receive a verification email at the address provided.

4. Click the link to complete the verification process.

Step 2: Install Git

Git is an open source version control application. You will need Git

installed for this class.

You may already have Git installed so let’s check! Open Terminal if you are

on a Mac, or Powershell if you are on a Windows machine, and type:

$ git --version

You should see something like this:

$ git --version

git version 2.6.3

Anything over 1.9.5 will work for this class!

2 | Getting Ready for Class

Downloading and Installing Git

If you don’t already have Git installed, you have two options:

1. Download and install Git at www.git-scm.com.

2. Install it as part of the GitHub Desktop package found at

desktop.github.com.

If you need additional assistance installing Git, you can find more

information in the ProGit chapter on installing Git: http://git-

scm.com/book/en/v2/Getting-Started-Installing-Git.

Where is Your Shell?

Now is a good time to create a shortcut to the command line application

you will want to use with Git:

• If you are working on Windows, you can use PowerShell or Git

Shell which is installed with the Git package.

• If you are working on a Mac or other Unix based system, you can use

the terminal application.

Go ahead and open your command line application now!

Step 3: Set Up Your Text Editor

For this class, we will use a basic text editor to interact with our code.

Let’s make sure you have one installed and ready to work from the

command line.

Pick Your Editor

You can use almost any text editor, but we have the best success with the

following:

• GitPad

• atom

• Vi or Vim

Step 3: Set Up Your Text Editor | 3

• Sublime

• Notepad or Notepad++

If you do not already have a text editor installed, go ahead and download

and install one of the above editors now!

Your Editor on the Command Line

After you have install an editor, confirm you can open it from the

command line. If you are working on a Mac, you will need to Install Shell

Commands from the Atom menu, this happens as part of the installation

process for Windows.

If installed properly, the following command will open the atom text editor:

$ atom .

Exploring

Congratulations! You should now have a working version of Git and a text

editor on your system. If you still have some time before class begins, here

are some interesting resources you can check out:

• github.com/explore Explore is a showcase of interesting projects in

the GitHub Universe. See something you want to re-visit? Star the

repository to make it easier to find later.

• training.github.com/kit The Training Kit is GitHub’s open source

training materials. The kit contains additional resources you may find

helpful when reviewing what you have learned in class! You can even

make contributions to the materials or open issues if you would like us

to explain something in greater detail!

4 | Getting Ready for Class

Getting Started With Collaboration

We will start by introducing you to Git, GitHub, and the collaboration

features we will use throughout the class. Even if you have used GitHub in

the past, we hope this information will provide a baseline understanding of

how to use it to build better software!

What is GitHub?

GitHub is a collaboration platform built on top of a distributed version

control system called Git.

Figure 1. GitHub’s beloved Octocat logo.

In addition to being a place to host and share your Git projects, GitHub

provides a number of features to help you and your team collaborate more

effectively. These features include:

• Issues

• Pull Requests

• Organizations and Teams

What is GitHub? | 5

Figure 2. Key GitHub Features.

Rather than force you into a "one size fits all" ecosystem, GitHub strives to

be the place that brings all of your favorite tools together. You may even

find some new, indispensable tools like continuous integration and

continuous deployment to help you and your team build software better,

together.

Figure 3. The GitHub Ecosystem.

What is Git?

Git is:

• a distributed version control system or DVCS.

• free and open source.

• designed to handle everything from small to very large projects with

speed and efficiency.

• easy to learn and has a tiny footprint with lightning fast performance.

Git outclasses many other SCM tools with features like cheap local

6 | Getting Started With Collaboration

branching, convenient staging areas, and multiple workflows.

As we begin to discuss Git (and what makes it special) it would be helpful

if you could forget everything you know about other version control

systems (VCSs) for just a moment. Git stores and thinks about

information very differently than other VCSs.

We will learn more about how Git stores your code as we go through this

class, but the first thing you will need to understand is how Git works with

your content.

Snapshots, not Deltas

One of the first ideas you will need understand is that Git does not store

your information as series of changes. Instead Git takes a snapshot of

your repository at a given point in time. This snapshot is called a commit.

Optimized for Local Operations

Git is optimized for local operation. When you clone a copy of a repository

to your local machine, you receive a copy of the entire repository and its

history. This means you can work on the plane, on the train, or anywhere

else your adventures find you!

Branches are Lightweight and Cheap

Branches are an essential concept in Git.

When you create a new branch in Git, you are actually just creating a

pointer that corresponds to the most recent snapshot in a line of work. Git

keeps the snapshots for each branch separate until you explicitly tell it to

merge those snapshots into the main line of work.

Git is Explicit

Which brings us to our final point for now; Git is very explicit. It does not

do anything until you tell it to. No auto-saves or auto-syncing with the

remote, Git waits for you to tell it when to take a snapshot and when to

send that snapshot to the remote.

What is Git? | 7

Exploring a GitHub Repository

A repository is the most basic element of GitHub. It is easiest to imagine

as a project’s folder. However, unlike an ordinary folder on your laptop, a

GitHub repository offers simple yet powerful tools for collaborating with

others. A repository contains all of the project files (including

documentation), and stores each file’s revision history. Whether you are

just curious or you are a major contributor, knowing your way around a

repository is essential!

Figure 4. GitHub Repositories.

Repository Navigation

Code

The code view is where you will find the files included in the

repository. These files may contain the project code, documentation,

and other important files. We also call this view the root of the

project. Any changes to these files will be tracked via Git version

control.

Issues

Issues are used to track bugs and feature requests. Issues can be

assigned to specific team members and are designed to encourage

8 | Getting Started With Collaboration

discussion and collaboration.

Pull Requests

A Pull Request represents a change, such as adding, modifying, or

deleting files, which the author would like to make to the repository.

Pull Requests are used to resolve Issues.

Wiki

Wikis in GitHub can be used to communicate project details, display

user documentation, or almost anything your heart desires. And of

course, GitHub helps you keep track of the edits to your Wiki!

Pulse

Pulse is your project’s dash board. It contains information on the

work that has been completed and the work in progress.

Graphs

Graphs provide a more granular view into the repository activity,

including who has contributed, when the work is being done, and

who has forked the repository.

README.md

The README.md is a special file that we recommend all repositories

contain. GitHub looks for this file and helpfully displays it below the

repository. The README should explain the project and point readers

to helpful information within the project.

CONTRIBUTING.md

The CONTRIBUTING.md is another special file that is used to

describe the process for collaborating on the repository. The link to

the CONTRIBUTING.md file is shown when a user attempts to create

a new issue or pull request.

Using GitHub Issues

Use GitHub issues to record and discuss ideas, enhancements, tasks, and

bugs. They make collaboration easier in a variety of ways, by:

• Replacing email for project discussions, ensuring everyone on the

team has the complete story.

Using GitHub Issues | 9

• Allowing you to cross-link to other issues and pull requests.

• Creating a single, comprehensive record of how and why you made

certain decisions.

• Allowing you to easily pull the right people into a conversation.

Activity: Creating A GitHub Issue

Follow these steps to create an issue in the class repository:

Activity Instructions

1. Click the Issues tab.

2. Click New Issue.

3. Type a subject line for the issue.

4. A - followed by a space and [ ] will create a handy checklist in your

issue or pull request.

5. When you @mention someone in an issue, they will receive a

notification - even if they are not currently subscribed to the issue or

watching the repository.

6. A # followed by the number of an issue or pull request (without a

space) in the same repository will create a cross-link.

7. Tone is easily lost in written communication. To help, GitHub allows

you to drop emoji into your comments. Simply surround the emoji id

with :.

Using Markdown

GitHub uses a syntax called Markdown to help you add basic text

formatting to issues.

Commonly Used Markdown Syntax

# Header

The `# ` indicates a Header. # = Header 1, ## = Header 2, etc.

* List item

A single * followed by a space will create a bulleted list. You can

also use a -.

10 | Getting Started With Collaboration

Bold item

Two asterix ** on either side of a string will make that text bold.

- [ ] Checklist

A - followed by a space and [ ] will create a handy checklist in your

issue or pull request.

@mention

When you @mention someone in an issue, they will receive a

notification - even if they are not currently subscribed to the issue or

watching the repository.

#975

A # followed by the number of an issue or pull request (without a

space) in the same repository will create a cross-link.

:smiley:

Tone is easily lost in written communication. To help, GitHub allows

you to drop emoji into your comments. Simply surround the emoji id

with :.

Activity: Creating A GitHub Issue | 11

Understanding the GitHub Flow

In this section, we will discuss the collaborative workflow enabled by

GitHub.

The Essential GitHub Workflow

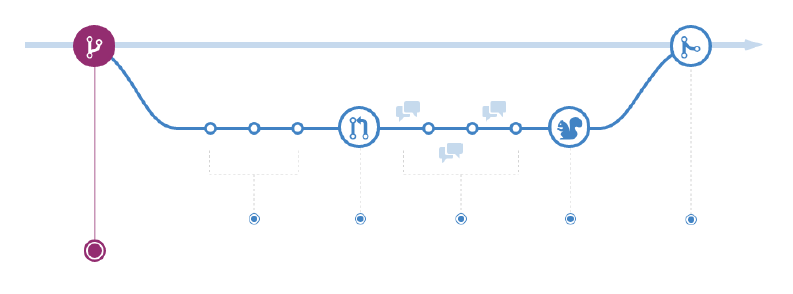

Figure 5. GitHub Workflow.

The GitHub flow is a lightweight workflow that allows you to experiment

with new ideas safely, without fear of compromising a project.

Branching is a key concept you will need to understand. Everything in

GitHub lives on a branch. By convention, the "blessed" or "canonical"

version of your project lives on a branch called master.

When you are ready to experiment with a new feature or fix an issue, you

create a new branch of the project. The branch will look exactly like

master at first, but any changes you make will only be reflected in your

branch. Such a new branch is often called a "feature" branch.

As you make changes to the files within the project, you will commit your

changes to the feature branch.

When you are ready to start a discussion about your changes, you will

open a pull request. A pull request doesn’t need to be a perfect work of art

- it is meant to be a starting point that will be further refined and polished

through the efforts of the project team.

When the changes contained in the pull request are approved, the feature

branch is merged onto the master branch. In the next section, you will

learn how to put this GitHub workflow into practice.

12 | Understanding the GitHub Flow

Branching with Git

The first step in the GitHub Workflow is to create a branch. This will allow

us to separate our work from the master branch.

Branching Defined

Figure 6. GitHub Workflow.

When you create a branch, you are essentially creating an identical copy of

the project at that point in time that is completely separate from the

master branch.

This keeps your the code on your master branch safe while you

experiment and fix issues.

Let’s learn how you can create a new branch.

Activity: Creating A Branch with GitHub

Earlier you created an issue about a change you would like to introduce

into the project. Let’s create a branch that you will use to add your file.

Follow these steps to create a new branch in the class repository:

Activity Instructions

1. Navigate to the class repository.

2. Click the branch dropdown.

3. Enter the branch name 'firstname-lastname-hometown'.

Branching Defined | 13

4. Press Enter.

When you create a new branch on GitHub, you are automatically switched

to your branch. Now, any changes you make to the files in the repository

will be applied to this new branch.

A word of caution. When you return to the repository or

click the top level repository link, notice that GitHub

automatically assumes you want to see the items on the

master branch. If you want to continue working on your

branch, you will need to reselect it using the branch

dropdown.

14 | Branching with Git

Local Git Configuration

In this section, we will prepare your local environment to work with Git.

Checking Your Git Version

First, let’s confirm your Git Installation:

$ git --version

$ git version 2.7.0

If you do not see a git version listed or this command returns an error, you

may need to reinstall Git.

To see what the latest version of Git is, visit www.git-

scm.com.

Git Configuration Levels

Figure 7. Git Configuration Levels.

Checking Your Git Version | 15

Git allows you to set configuration options at three different levels.

--system

These are system-wide configurations. They apply to all users on

this computer.

--global

These are the user level configurations. They only apply to your user

account.

--local

These are the repository level configurations. They only apply to the

specific repository where they are set.

The default value for git config is --local.

Viewing Your Configurations

$ git config --list

If you would like to see which config settings have been added

automatically, you can type git config --list. This will automatically

read from each of the storage containers for config settings and list them.

$ git config --global --list

You can also narrow the list to a specific configuration level by including it

before the list option.

Configuring Your User Name and Email

$ git config --global user.name "First Last"

$ git config --global user.email "[email protected]"

Git uses the config settings for your user name and email

address to generate a unique fingerprint for each of the

commits you create.

16 | Local Git Configuration

Configuring a Default Text Editor

$ git config --global core.editor "atom --wait"

Next, we will add the default text editor git will use when you need to edit

things like commit messages. If you have downloaded and installed the

open source text editor atom, the command shown above will configure it

properly.

If you are using a Mac, you will need to install the shell

commands from the Atom menu before the command

above will work.

If you would like to use a different editor you can find additional

instructions at https://help.github.com/articles/associating-text-editors-

with-git/

Configuring autocrlf

$ //for Windows users

$ git config --global core.autocrlf true

$ //for Mac or Linux users

$ git config --global core.autocrlf input

Different systems handle line endings and line breaks differently. If you

open a file created on another system and do not have this config option

set, git will think you made changes to the file based on the way your

system handles this type of file.

Memory Tip: autocrlf stands for auto carriage return line

feed.

Configuring Default Push Behavior

$ git config --global push.default simple

One final configuration option we will want to set is our default value for

push. When you push changes from your local computer to the remote you

Configuring a Default Text Editor | 17

can choose whether you want git to automatically push all of the local

branches to their matching branches on the remote or whether you only

want the currently checked out branch to be pushed. The config setting we

use to set this option is push.default. We can set the default to matching

if we want to push all branches automatically. OR, we can set it to simple

if we only want to push the branch we are on.

18 | Local Git Configuration

Working Locally with Git

If you prefer to work on the command line, you can easily integrate Git into

your current workflow.

Creating a Local Copy of the repo

Figure 8. Cloning a repository.

Before we can work locally, we will need to create a clone of the

repository.

When you clone a repository you are creating a copy of everything in that

repository, including its history. This is one of the benefits of a DVCS like

git - rather than being required to query a slow centralized server to review

the commit history, queries are run locally and are lightning fast.

Let’s go ahead and clone the class repository to your local desktop.

Activity Instructions

1. Navigate to the class repository on GitHub.

2. Copy the clone URL.

3. Open the CLI.

4. Type git clone <URL>.

5. Type cd <repo-name>.

Creating a Local Copy of the repo | 19

Our Favorite Git command: git status

$ git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

git status is a command you will use often to verify the current state

of your repository and the files it contains. Right now, we can see that we

are on branch master, everything is up to date with origin/master and our

working directory is clean.

Using Branches locally

$ git branch

If you type git branch you will see a list of local branches.

$ git branch --all

$ git branch -a

If you want to see all of the branches, including the read-only copies of

your remote branches, you can add the --all option or just -a.

The --all and -a are actually synonyms in Git. Git often

provides a verbose and a short option.

Switching Branches

$ git checkout <branch-name>

To checkout the branch you created online, type git checkout and the

name of your branch. You do not need to type remotes/origin in front

of the branch - only the branch name. You will notice a message that says

your branch was set up to track the same remote branch from origin.

20 | Working Locally with Git

Activity: Creating a New File

Activity Instructions

1. Clone the class repository to your local desktop.

2. Check out your branch.

3. Create a file named after your home town with the .md extension.

4. Save the file.

5. Close your text editor.

The Two Stage Commit

After you have finished making your changes, it is time to commit them.

When working from the command line, you will need to be familiar with the

idea of the two stage commit.

Figure 9. The Two Stage Commit - Part 1.

When you work locally, your files exist in one of four states. They are either

untracked, modified, staged, or committed.

An untracked file is one that is not currently part of the version controlled

directory.

Activity: Creating a New File | 21

Figure 10. The Two Stage Commit - Part 2.

To add these files to version control, you will create a collection of files

that represent a discrete unit of work. We build this unit in the staging

area.

Figure 11. The Two Stage Commit - Part 3.

When we are satisfied with the unit of work we have assembled, we will

commit everything in the staging area.

22 | Working Locally with Git

Figure 12. The Two Stage Commit - Part 4.

In order to make a file part of the version controlled directory we will first

do a git add and then we will do a git commit. Let’s do it now.

$ git status

$ git add my-file.md

$ git status

$ git commit

$ git status

When you type the commit command without any options, Git will open

your default text editor to request a commit message. Simply type your

message on the top line of the file. Any line without a # will be included in

the commit message.

Tips for Good Commit Messages

Good commit messages should:

• Be short. ~50 characters is ideal.

• Describe the change introduced by the commit.

• Tell the story of how your project has evolved.

Activity: Creating a New File | 23

Collaborating on Your Code

Now that you have made some changes in the project locally, let’s learn

how to push your changes back to the shared class repository for

collaboration.

Pushing Your Changes to GitHub

Figure 13. Pushing to GitHub.

Now that you have made some changes and committed them locally, it is

time to push them up to the remote. In this case, our remote is

GitHub.com, but this could also be your company’s internal instance of

GitHub Enterprise.

To push your changes to GitHub, you will use the command:

$ git push -u origin <branch-name>

The -u is the short version of the option --set

-upstream. This option tells Git to create a relationship

between our local branch and a remote tracking branch of

the same name.

24 | Collaborating on Your Code

Activity: Creating a Pull Request

Pull Requests are used to propose changes to the project files. A pull

request introduces an action that addresses an Issue. A Pull Request is

considered a "work in progress" until it is merged into the project.

Now that you have created a file, you will open a pull request to discuss

the file with your team mates. Follow these steps to create a Pull Request

in the class repository:

Activity Instructions

1. Click the Pull Request icon.

2. Click New Pull Request.

3. In the base dropdown, choose master

4. In the compare dropdown, choose your branch.

5. Type a subject line and enter a comment.

6. Use markdown formatting to add a header and a checklist to your Pull

Request.

7. @mention the teacher.

8. Use one of the keywords closes, fixes, or resolves to note which

Issue the Pull Request resolves.

9. Use Preview to see how your Pull Request will look.

10. Assign the Pull Request to yourself.

11. Click Create Pull Request.

When you navigate to the class repository, you should see

a banner at the top of the page indicating you have recently

pushed branches, along with a button that reads Compare

& pull request. This helpful button will automatically start

the pull request process between your branch and the

repository’s default branch.

Exploring a Pull Request

Now that we have created a Pull Request, let’s explore a few of the

Activity: Creating a Pull Request | 25

features that make Pull Requests the center of collaboration:

Conversation view

Similar to the discussion thread on an Issue, a Pull Request contains

a discussion about the changes being made to the repository. This

discussion is found in the Conversation tab and also includes a

record of all of the commit that have been made on the branch.

Commits view

The commits view contains information about who has made

changes to the files. Each commit is an updated view of the

repository, allowing us to see how changes have happened from

commit to commit.

Files changed view

The Files changed view allows you to see the change that is being

proposed. We call this the diff. Notice that some of the text is

highlighted in red. This is what has been removed. The green text is

what has been added.

Code Review in Pull Requests

To provide feedback on proposed changes, GitHub offers two levels of

commenting:

General Conversation

You can provide general comments on the Pull Request within the

Conversation tab.

Line Comments

In the files changed view, you can hover over a line to see a blue +

icon. Clicking this icon will allow you to enter a comment on a

specific line. These line level comments are a great way to give

additional context on recommended changes. They will also be

displayed in the conversation view.

Exploring

Here are some additional resources you may find helpful:

26 | Collaborating on Your Code

• guides.github.com/features/mastering-markdown/ An interactive

guide on using Markdown on GitHub.

Exploring | 27

Editing Files on GitHub

Since you created the pull request, you will be notified when someone

adds a comment. In this case, the comment may ask you to make a

change to the file you just created. Let’s see how GitHub makes this easy.

Editing a File on GitHub

To edit a pull request file, you will need to access the Files Changed view.

Click the edit icon to access the GitHub file editor.

Committing Changes on GitHub

Once you have made some changes to your file, you will need to create a

new commit.

Remember, a good commit message should describe what was changed

in the present tense. For example, Add favorite color.

Since we accessed our file through the pull request, GitHub helpfully

directs us to commit our changes to the same branch. Choose the option

to Commit directly to your branch and click Commit changes.

If you want to see what was changed in a specific commit,

you can go to the Commits tab and click on the Commit ID

you would like to view.

28 | Editing Files on GitHub

Merging Pull Requests

Now that you have made the requested changes, your pull request should

be ready to merge.

Merge Explained

When you merge your branch, you are taking the content and history from

your feature branch and adding it to the content and history of the master

branch.

Figure 14. Merge visual.

Many project teams have established rules about who

should merge a pull request. Some say it should be the

person who created the pull request since they will be the

ones to deal with any issues resulting from the merge.

Others say it should be a single person within the project

team to ensure consistency. Still others say it can be

anyone other than the person who created the pull request.

This is a discussion you should have with the other

members of your team.

Merge Explained | 29

Merging Your Pull Request

Let’s take a look at how you can merge the pull request.

First, let’s use some emoji to indicate we have checked over the Pull

Request and it looks good to merge. We like to use :+1: :ship: or :shipit:.

Activity Instructions

1. Open the Pull Request to be merged

2. Open the Conversation view

3. Scroll to the bottom of the Pull Request and click the Merge pull

request button

4. Type your merge commit message

5. Click Confirm merge

6. Click Delete branch

7. Click Issues and confirm your original issue has been closed

Cleaning Up Your Branches

When you merged your Pull Request, you deleted the branch on GitHub,

but this will not automatically delete your local copy of the branch. Let’s go

back to our Terminal and do some cleanup.

$ git checkout master

$ git pull ¬

$ git branch --all ¬

①

retrieves all of the changes from GitHub and brings them down to your

local machine.

②

shows you all of the branches that exist locally, both ones you can work

with and the read-only copies of the remote tracking branches.

You will probably see that your branch is still there, both as a local branch

and as a read-only remote tracking branch.

$ git branch --merged

30 | Merging Pull Requests

Adding the --merged option to the git branch command allows you to

see which branches have history equivalent to the history on the checked

out branch. In this case, since we are checked out to master, we will use

this command to ensure all of the changes on our feature branch have

been merged to master before we delete the branch.

To delete the local branch, type the following command:

$ git branch -d <branch-name>

If you type git branch --all again, you will see that your local branch

is gone but the remote tracking branch is still there. To delete the remote

tracking branch, type:

$ git pull --prune

If you would like pruning of the remote tracking branches

to be set as your default behavior when you pull, you can

use the following configuration option: git config

--global fetch.prune true.

Merging Your Pull Request | 31

Viewing Local Changes

Now that you are familiar with the basic workflow, let’s explore some of

the powerful Git and GitHub features that will help you work with your

code.

Different Commands for Viewing Changes

Figure 15. Git Diff Options.

The git diff command allows you to see the difference between files in

the working and staging directories and what is in your history.

$ git diff

$ git diff --staged

$ git diff HEAD

$ git diff --color-words

32 | Viewing Local Changes

Viewing Local Project History

In this section, you will discover commands for viewing the history of your

project.

Using Git Log

When you clone a repository, you receive more than just the files in that

the repository. You also receive the history of all of the commits made in

that repository.

Let’s take a look at some of the option switches you can use with the log

command to customize your view of the project history.

$ git log

$ git log --oneline

$ git log --oneline --graph

$ git log --oneline --graph --decorate

$ git log --oneline --graph --decorate --all

$ git log --stat

$ git log --patch

Use the up and down arrows or press enter to view

additional log entries. Type q to quit viewing the log and

return to the command prompt.

Using Git Log | 33

Fixing Commit Mistakes

In this section, we will begin to explore some of the ways Git and GitHub

can help us shape our project history.

Changing Commits

Commit amend allows us to fix mistakes in our last commit. Two of the

most common uses are:

• Re-writing commit messages

• Adding files to the commit

When you are adding files to the previous commit, the files to be added

should be in the staging area when you type the git commit --amend

command.

$ git commit --amend

You can actually amend any data stored by the last commit

such as commit author, email, etc.

34 | Fixing Commit Mistakes

Streamlining Your Workflow with Aliases

So far we have learned quite a few commands. Some, like the log

commands, can be long and tedious to type. In this section, you will learn

how to create custom shortcuts for Git commands.

Creating Custom Aliases

An alias allows you to type a shortened command to represent a long

string on the command line.

For example, let’s create an alias for the log command we learned earlier.

Original Command

$ git log --oneline --graph --decorate --all

Creating the Alias

$ git config --global alias.lol "log --oneline --graph

--decorate --all"

Using the Alias

$ git lol

Other Common Aliases

$ git config --global alias.co "checkout -b"

$ git config --global alias.ss "status -s"

Explore

Check out this resource for a list of common aliases:

• git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Basics-Git-Aliases A helpful overview of

some of the most common git aliases.

Creating Custom Aliases | 35

Workflow Review Project: GitHub Games

In this section, we will complete a project using the GitHub Flow.

User Accounts vs. Organization Accounts

There are two major account types in GitHub, user accounts and

organization accounts. While there are many differences in these account

types, on of the more notable differences is how you handle permissions.

User Accounts

Our first class repository was in a user account for GitHub Teacher.

Permissions for a user account are simple, you simply add people as

collaborators to give them full read-write access to the project.

Organization Accounts

Organization accounts provide more granular control over repository

permissions. In an organization account you will create teams of

people and then give those teams access to specific repositories.

You can also designate the type of access a team should have (e.g,

read only, read-write, or admin).

What is a Fork?

A fork is a full copy of a repository that resides on a different account.

They are easiest to understand in the context of Open Source, but are also

commonly used in organizations to control who can merge a pull request.

Essentially, you will use a fork to make changes to a repository when you

do not have write access. At the moment you create the fork, it is an exact

duplicate of the parent repository.

Creating a Fork

Activity Instructions

1. Navigate to the repo githubschool/github-games.

2. Click Fork.

3. Select the account you would like the fork to reside.

36 | Workflow Review Project: GitHub Games

Introduction to GitHub Pages

GitHub Pages enable you to host a free, static web page directly from your

GitHub repository. The github-games project will use GitHub Pages. We

will barely scratch the surface in this class, but there are a few things you

need to know:

• You can create two types of websites, a user/organization site or a

project site. We are creating a project website.

• For a project site, GitHub will look for a special gh-pages branch and

only serve the content on that branch.

• The rendered site for your fork will appear at

username.github.io/github-games.

Workflow Review: Updating the README.md

First, let’s practice the GitHub Flow from beginning to end by updating the

link in the README to point to your fork of the repository.

We have intentionally left these steps very high level since they are a

review. If you need help with any of these steps, refer to the earlier section

of this manual:

Workflow Review Activity

1. Clone your fork of the repository locally.

2. Create a new branch called readme-update.

3. Make changes to the README.md.

4. Commit the changes to your branch.

5. Push your branch to GitHub.

6. Create a Pull Request in your repository.

7. Merge your changes.

8. Delete the branch.

9. Update your local copy of the repository.

Introduction to GitHub Pages | 37

Reverting Commits

In this section, we will learn about commands that re-write history and

understand when you should or shouldn’t use them.

How Commits Are Made

Every commit in Git is a unique snapshot of the project at that point in

time. It contains the following information:

• The version of every blob in the repository

• The author of the commit

• The author’s email

• The date and time of the commit

• The commit message

Figure 16. Commit and tree structure.

Each commit also contains the commit ID of its parent commit.

38 | Reverting Commits

Figure 17. Parents and Children.

Image source: ProGit v2 by Scott Chacon

Safe Operations

Git’s data structure gives it integrity but its distributed nature also requires

us to be aware of how certain operations will impact the integrity of the

data that has been shared.

If an operation will change a commit ID that has already been pushed to

the remote (also known as a public commit), we must be careful in

choosing the operations to perform.

Table 1. Guidelines for Common Commands

Command Cautions

revert Generally safe since it creates a new

commit.

amend Only use on local commits.

reset Only use on local commits.

cherry-pick Only use on local commits.

rebase Only use on local commits.

Reverting Commits with git revert

To get your game working, you will need to reverse the commit that

incorrectly renames index.html.

Activity Instructions

1. Use git log to find the commit where the rename occurred.

2. Type git revert <SHA>.

Safe Operations | 39

3. Type a commit message.

4. Push your changes to GitHub.

40 | Reverting Commits

Resolving Merge Conflicts

Merge conflicts can be intimidating, but resolving them is actually quite

easy. In this section you will learn how!

Local Merge Conflicts

To practice merge conflicts, we first need to create one. Complete the

following:

Activity Instructions

1. Type git checkout -b stats-update origin/stats-update.

2. Type git diff —color-words gh-pages..stats-update.

3. Check out the gh-pages branch.

4. Merge the stats-update branch into gh-pages.

You should receive a conflict message similar to the one shown below:

$ git checkout gh-pages

Switched to branch 'gh-pages'

$ git merge stats-update

Auto-merging index.html

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in index.html

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the

result.

Use git status to determine which file(s) are in conflict.

Open the conflicting file in your text editor.

<<<<<<<<< HEAD

Some text

=========

Some more text

>>>>>>>>> stats-update

Activity Instructions

1. Choose which version of the code you would like to keep.

2. Remove the conflict markers.

Local Merge Conflicts | 41

3. Save the file.

4. Close the text editor.

5. Type git status.

6. Type git add index.html.

7. Type git commit -m "resolving merge conflict".

Remote Merge Conflicts

Activity Instructions

1. Checkout a local copy of the shape-colors branch.

2. Go to lines 115-121 of the index file and change around some of the

colors.

3. Stage and commit the changes.

4. Push to GitHub and create a Pull Request.

5. Use the command line instructions shown on GitHub to resolve the

conflict.

Exploring

Finished and want to do more? Here are some things you can do:

• Add a new background to the game.

42 | Resolving Merge Conflicts

Helpful Git Commands

In this section, we will explore some helpful Git commands.

Moving and Renaming Files with Git

Activity Instructions

1. Create a new branch named slow-down.

2. Change the background url to (images/texture.jpg).

3. Change the timing for the game to speed it up or slow it down.

4. Type git status.

5. Type mkdir images.

6. Type git mv texture.jpg images/texture.jpg.

Staging Hunks of Changes

Crafting atomic commits is an important part of creating a readable and

informative history of the project.

Activity Instructions

1. Type git status.

2. Type git add -p.

3. Stage the hunk related to the image move.

4. Commit your changes.

5. Stage and commit the speed change.

6. Push your changes to GitHub.

Moving and Renaming Files with Git | 43

Rewriting History with Git Reset

In this section, you will learn how to re-write history with Git.

Understanding Reset

Sometimes we are working on a branch and we decide things aren’t going

quite like we had planned. We want to reset some, or even all, of our files

to look like what they were at a different point in history. We can do that

with git reset.

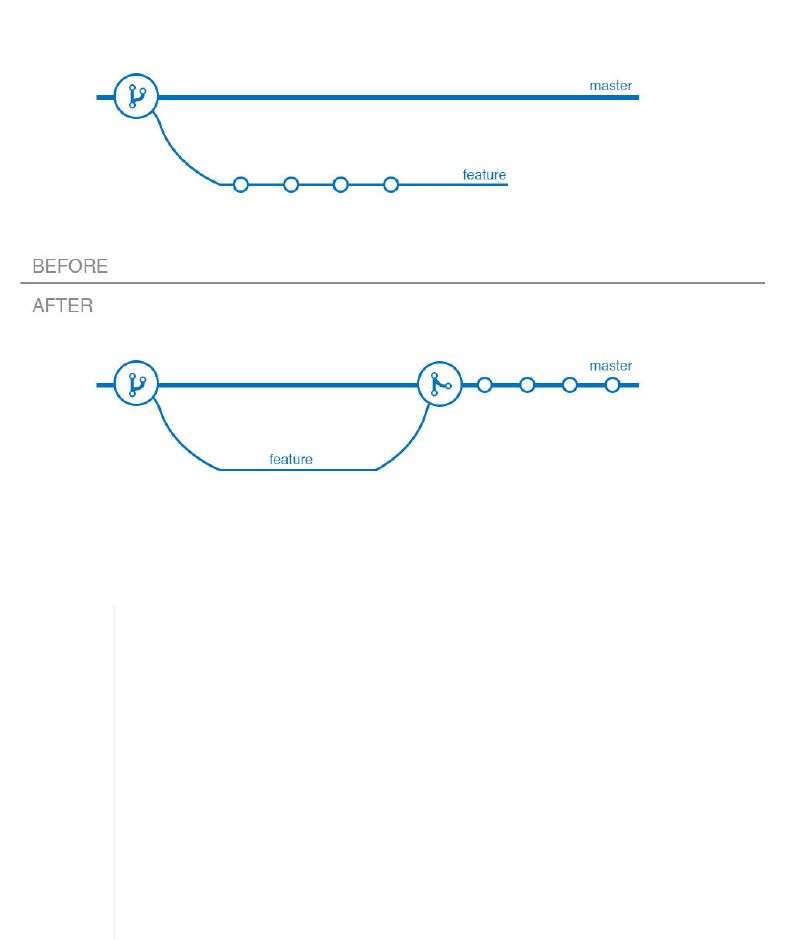

Figure 18. Git Reset Before and After.

Remember, there are three different snapshots of our project at any given

time. The first is the most recent commit. The second is the staging area

(also called the index). The third is the working directory (i.e. whatever you

currently have saved on disk). The git reset command has three

modes, and they allow us to change some or all of these three snapshots.

It also helps to know what branches technically are: each is a pointer, or

reference, to the latest commit in a line of work. As we add new commits,

the currently checked-out branch "moves forward," so that it always points

to the most recent commit.

44 | Rewriting History with Git Reset

Reset Modes

Figure 19. The three modes of reset.

The three modes for git reset are: --soft, --mixed, and --hard. For

these examples, assume that we have a "clean" working directory, i.e.

there are no uncommited changes.

soft

git reset --soft <my-branch> <other-commit> moves

<my-branch> to point at <other-commit>. However, the working

directory and staging area remain untouched. Since the snapshot

that <my-branch> points to now differs from the index’s snapshot,

this command effectively stages all differences between those

snapshots. This is a good command to use when you have made a

large number of small commits and you would like to regroup them

into a single commit.

mixed

With the --mixed option, Git makes <my-branch> and the staging

area look like the <other-commit> snapshot. This is the default

mode: if you don’t include a mode flag, Git will assume you want

Reset Modes | 45

--mixed. --mixed is useful if you want to keep all of your changes

in the working directory, but change whether and how you commit

those changes.

hard

--hard is the most drastic option. With this, Git will now make all 3

snapshots, <my-branch>, the staging area, and your working

directory, look like they did at <other-commit>. This can be

dangerous! We’ve assumed so far that our working directory is

clean. If it is not, and you have uncommited changes, git reset

--hard will delete all of those changes. Even with a clean working

directory, use --hard only if you’re sure you want to completely

undo earlier changes.

Next we will try out each of these options.

Creating a Local Repository

Since git reset rewrites history, you should avoid using it on commits

that have already been made public (e.g. pushed to the repository on

GitHub).

To avoid teaching you bad habits, we will create a practice repository. This

time, we will start the repository locally, from the command line.

Activity Instructions

1. Navigate to the directory where you will place your practice repo.

2. Type git init practice-repo.

3. Type cd practice-repo.

4. Create a README.md file and use it as your initial commit.

Reset Soft

To prepare for this activity, you will need to create four files and commit

each separately so your file directory looks like this:

46 | Rewriting History with Git Reset

$ ls

file1.md

file2.md

file3.md

file4.md

README.md

And your history looks like this:

$ git log --oneline

fj8weq4 init file 4

3487nio init file 3

39dj58s init file 2

dke03md init file 1

84nqdkq initializing repo with README

Now that your repository is set up, let’s try our first reset.

1. Use the log alias we created earlier to look at the history of our project.

2. Identify the current location of HEAD.

3. We want to go back two commits in our history so we will type git

reset --soft HEAD~2.

4. Type git status. The changes we made in the last two commits

should be in the staging area waiting to be committed.

5. Using the log command, we can see that the HEAD is now sitting two

commits earlier than it was before we used git reset.

6. Go ahead and re-commit these changes with git commit -m

"grouping commits for cleaner history".

In this example, the tilde tells git we want to reset to two

commits before the current location of HEAD. You can also

use the first few characters of the commit ID to pinpoint

the location where you would like to reset HEAD.

Reset Mixed

After the soft reset, your file directory should still look like this:

To prepare for this activity, you will need to create four files and commit

Reset Mixed | 47

each separately so your file directory looks like this:

$ ls

file1.md

file2.md

file3.md

file4.md

README.md

But your history should now look like this:

$ git log --oneline

78fjuoz grouping commits for cleaner history

39dj58s init file 2

dke03md init file 1

84nqdkq initializing repo with README

Next we will try the mixed reset:

1. Once again, we will start by viewing the history of our project.

2. This time we only want to go back one commit in history so we will

type git reset HEAD~ OR git reset <SHA>.

3. Type git status. The changes we made in the last commit have

been moved back to the working directory.

4. This time, we will need to git add the files to the staging area before

we can commit them.

5. Go ahead and re-commit the files with git commit -m "another

reset example".

Remember, mixed is the default mode for the reset

command.

Reset Hard

Last but not least, let’s try a hard reset.

1. Start by viewing the history of our project.

2. This time we reset to the point in time where the only file that existed

was the README.md. Type git reset --hard <SHA>.

48 | Rewriting History with Git Reset

3. Type git status. Notice your working directory is clean.

4. Viewing the history of your project will reveal a single commit.

Remember, git reset --hard is a destructive

command. Don’t use it unless you really want to discard

your changes.

Does Gone Really Mean Gone?

The answer: It depends!

Type the command git reflog.

The reflog is a record of every place HEAD has been. In a few minutes we

will see how the reflog can be helpful in allowing us to retrieve changes we

didn’t mean to discard. But first, we need to be aware of some of the

reflog’s limitations:

• The reflog only includes your local history. In other words, you can’t see

the reflog for someone else’s local commits and they can’t see yours.

• The reflog is a limited time offer. By default, reachable commits are

held in the reflog for 90 days, but unreachable commits (meaning

commits that are not attached to a branch) are only kept for 30 days.

Exploring

Here are some interesting things you can check out later:

• guides.github.com/introduction/flow/ An interactive review of the

GitHub Workflow.

Does Gone Really Mean Gone? | 49

Cherry Picking

We just learned how reflog can help us find local changes that have been

discarded. So what if:

You Just Want That One Commit

Cherry picking allows you to pick up a commit from one branch of the

project and move it to your current branch. Right now, your file directory

and log should look like this:

$ ls

README.md

$ git lol

84nqdkq initializing repo with README

Let’s try it:

1. Create and checkout to a new branch named cherry-picking.

2. Using the reflog, find the commit ID where you added file2.md.

3. Type git cherry-pick <SHA>.

Now when you view your directory and log, you should see:

$ ls

file2.md

README.md

$ git lol

eanu482 init file 2

84nqdkq initializing repo with README

Remember, when using any commands that change

history, it’s important to make these changes to your

commits before pushing to GitHub. Any time you change

the commit ID of something in shared history, you risk

creating problems. Others working with the same

repository won’t have the re-written history.

Is the commit ID the same as the one you used in the cherry pick

command? Why or why not?

50 | Cherry Picking

Merge Strategies: Rebase

In this section, we will discuss another popular merge strategy, rebasing.

About Git rebase

The rebase command enables you to modify your commit history in a

variety of ways. For example, you can use it to reorder commits, edit them,

squash multiple commits into one, and much else.

To enable all of this, rebase comes in several forms. For today’s class,

we’ll be using interactive rebase: git rebase --interactive, or git

rebase -i for short.

Typically, you would use git rebase -i to:

• Edit previous commit messages

• Combine multiple commits into one

• Delete or revert commits that are no longer necessary

Because changing your commit history can make things

difficult for everyone else using the repository, it’s

considered bad practice to rebase commits you’ve already

pushed to a repository.

Rebasing commits against a branch

To rebase all the commits between another branch and the current branch

state, you can enter the following command in your shell (either the

command prompt for Windows, or the terminal for Mac and Linux):

git rebase --interactive other_branch_name

Rebasing commits against a point in time

To rebase the last few commits in your current branch, you can enter the

following command in your shell:

git rebase --interactive HEAD~7

About Git rebase | 51

Figure 20. Git Rebase.

Activity: Git Rebase Practice

Activity Set Up Instructions

1. Type git checkout -b rebase-me.

2. Create 2-3 new files on your branch (HINT: you can use touch

file1.md file2.md file3.md).

3. Add and commit each file seperately.

4. Type git checkout master.

5. Create 2-3 new files on master (e.g. touch file4.md file5.md

file6.md).

6. Take a look at your history by typing git log --oneline --graph

--decorate --all.

Begin the Rebase

1. Type git checkout rebase-me.

2. Start the merge by typing git rebase -i master.

3. Your text editor will open, allowing you to see the commits to be

rebased.

4. Save and close the rebase-todo.

5. Watch your rebase happen on the Command Line.

Check it Out

1. See your cool changes by typing git log --oneline --graph

--decorate --all.

2. Go back to master by typing git checkout master.

3. Merge your changes in to master by typing git merge rebase-me.

52 | Merge Strategies: Rebase

Appendix A: Talking About Workflows

Discussion Guide: Team Workflows

Here are some topics you will want to discuss with your team as you

establish your ideal process:

1. Which branching strategy will we use?

2. Which branch will serve as our "master" or deployed code?

3. Will we use naming conventions for our branches?

4. How will we use labels and assignees?

5. Will we use milestones?

6. Will we have required elements of Issues or Pull Requests (e.g.

shipping checklists)?

7. How will we indicate sign-off on Pull Requests?

8. Who will merge pull requests?

Discussion Guide: Team Workflows | 53