Kennesaw State University

DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University

!#3+263"+)#!2).-1

Culture Determines Business Models: Analyzing

Home Depot's Failure Case in China for

International Retailers from a Communication

Perspective

May Hongmei Gao

Kennesaw State University,'!.*%--%1!5%$3

.++.52()1!-$!$$)2).-!+5.0*1!2 (9/$)')2!+#.,,.-1*%--%1!5%$3&!#/3"1

!02.&2(% -2%0-!2).-!+31)-%11.,,.-1

8)102)#+%)1"0.3'(22.6.3&.0&0%%!-$./%-!##%11"6)')2!+.,,.-1%--%1!52!2% -)4%01)262(!1"%%-!##%/2%$&.0)-#+31).-)-!#3+26

3"+)#!2).-1"6!-!32(.0)7%$!$,)-)120!2.0.&)')2!+.,,.-1%--%1!52!2% -)4%01)26.0,.0%)-&.0,!2).-/+%!1%#.-2!#2

$)')2!+#.,,.-1*%--%1!5%$3

%#.,,%-$%$)2!2).-

!.!6.-',%)3+230%%2%0,)-%131)-%11.$%+1-!+67)-'.,%%/.21!)+30%!1%)-()-!&.0-2%0-!2).-!+%2!)+%01

&0.,!.,,3-)#!2).-%01/%#2)4%83-$%0")0$-2%0-!2).-!+31)-%11%4)%50)-2

173

FEATURE ARTICLE

Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com)

© 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. • DOI: 10.1002/tie.21534

Correspondence to: May Hongmei Gao, Kennesaw State University–Communication, 1000 Chastain Road MD#2207, Kennesaw, Georgia 30144, 770-598-7009

(phone), 770-423-6740 (fax), [email protected]

This article is a result of a longitudinal case study regarding Home Depot’s operation in China. From

2006 to 2011, the author conducted 37 in-depth interviews with Home Depot executives, managers,

lawyers, employees, suppliers, and consumers, as well as its Western and Chinese competitors.

These interviews generated 500+ pages of transcripts and eld notes. Home Depot entered China in

2006 by acquiring 12 stores from a Chinese company, Home Way. However, by September 2012 all

Home Depot stores in China had been closed.

Culture Determines

Business Models:

Analyzing Home Depot’s

Failure Case in China for

International Retailers

from a Communication

Perspective

By

May Hongmei Gao

174

FEATURE ARTICLE

Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013 DOI: 10.1002/tie

This article uses the Home Depot’s operation in China as

a case study to stress that “culture” determines business

models for international retailers. This article strives to

generate a framework of host culture analysis for inter-

national retailers to find a proper business model in a

foreign market.

Industry insiders say many foreign companies have

been too rigid with their approach of business models

to the China market. “You have to be nimble and willing

to react quickly to changes,” said Peter Lau, chairman

of Hong Kong–based apparel retailer Giordano Inter-

national Ltd. Mr. Lau said he encourages regional and

individual managers at his nearly 1,400 Giordano outlets

in China to create local marketing and sales models.

The people on the ground know their customers better

than employees in corporate head offices, Mr. Lau said

(Burkitt, 2012).

Borrowing from its strategy in the United States,

Home Depot operated with a Do-It-Yourself (DIY) business

This interview-based single-case-study research has these notable contributions. First, this research

stresses the importance of host culture in creating a business model when an international retailer

expands to a foreign country. Second, the research develops a new Host Culture Analysis Frame-

work: CELM (host Culture, business Environment, target consumer Lifestyle, and target consumer

Mentality). Third, by applying the CELM framework to the Chinese market, this research suggests

that Home Depot could have replaced its ineffective DIY (Do-It-Yourself) model with the new DIFM

(Do-It-for-Me) business model for China. Fourth, this article proposes a new urban boutique store

(UBS) retail format for international retailers

entering emerging markets.

Finally, this research shows

that in-depth interview is a solid research method to be applied to case studies, for the discovery of

deeper reasons of international expansion failures. © 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Introduction

I

n 2010, China surpassed Japan and became the second-

largest economy in the world (Hamlin & Li, 2010).

China is projected to surpass the US economy and

become the largest economy by 2030 (Torres, 2011). In

2011, American companies such as General Motors and

Kentucky Fried Chicken announced that, for the first time,

they made more sales in China than in the United States.

However, the emerging Chinese market, with its dis-

tinct Chinese cultural elements, poses great challenges

for international retailers (Letovsky, Murphy, & Kenny,

1997). On September 15, 2012, the Wall Street Journal

reported that Home Depot Inc. decided to close all seven

of its remaining big-box stores in China and to pull out

of China after six years of losses (Burkitt, 2012). Home

Depot joins a growing list of American retailers who

have stumbled in China. Mattel Inc. shut its China-based

Barbie flagship store in March 2011 after it learned that

conservative Chinese parents would rather have their

children read books than spin a sexy doll in a plastic Cor-

vette. In February 2011, five years after entering China in

2006, Best Buy shut down all nine of its branded stores,

after discovering that Chinese consumers needed wash-

ing machines and air conditioners more than espresso

makers and surround-sound stereo systems (Burkitt,

2012; MacLeod, 2011; Schmitz, 2011). The retreat by

Home Depot, Mattel and Best Buy highlight the difficul-

ties that international retailers encounter while doing

business in China, with over 1.3 billion consumers.

The popular mentality of international expansion

for American businesses has been the strategy that “If it’s

good enough for us, it will be good enough for them.”

However, this perspective of moving a business model

from the United States and using it exactly the same way

in a foreign country has shown cases of failure in China.

Industry insiders say many

foreign companies have been

too rigid with their approach

of business models to the

China market.

Culture Determines Business Models: Analyzing Home Depot’s Failure Case in China for International Retailers from a Communication Perspective

175

DOI: 10.1002/tie Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013

1. To demonstrate the cultural challenges of an interna-

tional retailer doing business in China.

2. To propose CELM (Culture, business Environment,

consumer Lifestyle, consumer Mentality), a new “host

culture analysis framework” for international retailers

entering foreign markets.

3. To develop DIFM (Do-It-for-Me), a “new business

model” for an international retailer, such as Home

Depot, after applying the CELM analysis framework.

4. To suggest UBS (urban boutique store), a “next

generation store format concept” for international

retailers.

5. To showcase the effectiveness of using qualitative

in-depth interviews and systematic observation as a

research method to enrich case studies.

China expects its urbanization rate to rise from 47.5%

in 2010 to 51.5% by the end of 2015, according to the

12th Five-Year Plan (Xinhua News Agency, 2011). Clearly,

the Chinese economy is booming and China is quickly

urbanizing. Investment analyst Meyers (2011) stated that

a home improvement company such as Home Depot is

very sensitive to positive economic growth, especially the

growth in housing and urbanization areas. A booming

housing market such as the one in China should boost

the business of Home Depot. Why did Home Depot fail

in China?

This article is a result of a longitudinal case study with

in-depth interviews and systematic observation regarding

Home Depot’s operation in China. From 2006 to 2010, the

author conducted 37 in-depth interviews in China and the

United States with Home Depot executives, store manag-

ers, employees, and consumers, as well as its international

and Chinese competitors. By analyzing the key customer

segment in the target market for Home Depot—“urban

model in a Big-Box retailing format in China. In 2009,

Frank Blake, chairman and CEO of Home Depot, said at

a Bank of America–Merrill Lynch consumer conference:

“We’re still not confident we’ve got the right business

model.” In 2011 Blake said the company’s business in

China remained “problematic” and that the company was

working to build a profitable business model by focusing

on “select” Chinese cities (Yung, 2011). However, the

recent retreat from China indicates Home Depot never

found a proper business model for the Chinese market.

This article intends to suggest a new business model of

DIFM for international retailers such as Home Depot to

operate in China successfully.

While the attention given to emerging markets in

the retailing literature has been minimal, retailing inter-

nationalization has been widely discussed in the current

marketing literature (Arnold & Quelch, 1998; Eckhardt,

2005; Hoskisson, Eden, Lau, & Wright, 2000; Khanna &

Palepu, 2006; Kim, Kandemir, & Cavusgil, 2004; Walters

& Samiee, 2003; Yiu, Bruton, & Lu, 2005; Zhang, Zhang,

& Liu, 2007). Gandolfi and Strach (2009) studied the

case of Walmart’s retreat from South Korea. Walmart,

the world’s largest retailer, failed to capture the hearts

of South Korean consumers, ultimately withdrawing in

2006 after eight years in the market. Walmart is only one

among several retailers that have underestimated the

role of cultural due diligence prior to entry into a foreign

country. K-Mart and Carrefour in the Czech Republic,

Ahold in China, Lane Crawford in Singapore, Tesco and

Toys “R” Us in France, C&A in the United Kingdom, and

Home Depot stores in Chile (Burt, Dawson, & Sparks,

2003) are prime failure examples of international retail-

ers in foreign markets.

Research has provided evidence that retailers may

falter when establishing international operations. An

international retailer who fails to create a business model

compatible with local cultures usually results in a com-

plete shutdown or sale of its operation to a local chain

or to an international retailer already established in the

local market. The primary managerial implication is that

the local culture determines the business model for an

international retailer. The secondary managerial impli-

cation is that international retailers usually retreat from

a foreign market after seven years of losses (Burt et al.,

2003). Bianchi (2008) stresses that the failure of interna-

tional retailers may be due to their insufficient adaptation

to local cultures.

Built upon this body of work, this research focuses

on the impact of culture on business models for interna-

tional retailers in emerging markets, such as China. The

purpose of this article is fivefold:

A booming housing market

such as the one in China

should boost the business

of Home Depot. Why did

Home Depot fail in China?

176

FEATURE ARTICLE

Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013 DOI: 10.1002/tie

new three-bedroom, two-bath condominium in urban

China need to fix the basics, such as flooring, painting,

plumbing, light fixtures, and home appliances. This phe-

nomenon creates a daunting task for homeowners and

generates a huge market for products and services for

home improvement retailers in China.

Founded in 1978, Home Depot, Inc. is the world’s

largest home improvement specialty retailer, and the

fourth-largest retailer in the United States. The com-

pany’s fiscal 2010 retail sales were $68.0 billion, and

earnings from continuing operations were $3.3 billion.

Currently, the company has more than 2,200 retail stores

in the United States, Canada, Mexico, Puerto Rico, the

US Virgin Islands, and China. The company was ranked

No. 30 on the Fortune 500 list in 2010 (CNN, 2011; Home

Depot, 2011).

Home Depot entered China in 2006 by acquiring

12 stores from the Chinese home improvement com-

pany Home Way, China’s first big-box home improve-

ment retailer (China Daily, 2011). In 2006, Home Depot

employed 3,000 associates and operated 12 stores across

six cities in China—Tianjin (5), Beijing (2), Xi’an (2),

Qingdao (1), Shenyang (1), and Zhengzhou (1). Tianjin

was the anchor city because it was the headquarters of

Home Way. Home Depot China’s store format was big-

box operation, with an average of 90,000 square feet per

store, based on a DIY model developed in the United

States. The stores offer such services as delivery, instal-

lation, design, and remodeling (Home Depot, 2010).

The Chinese translation for Home Depot is “Jia De Bao

(

),” which literally means “getting treasures for

your home”.

Home Depot has closed all 12 stores that it purchased

from Home Way in 2006. In May 2009 Home Depot

suddenly closed its storefront in Qingdao, Shandong

Province, a coastal city in East China. The official excuse

for the closure was “renovation by the landlord.” The

employees of the store were disappointed with the sud-

den closure and actually took control of the store for a

short period of time (China Business Focus, 2009). On the

surface, the quickly expanding home improvement mar-

ket seems to create an “ideal” opening for Home Depot.

Why did Home Depot fail in China? How can an interna-

tional retailer succeed in China? This article searches for

answers to these research questions:

1. To what extent can the local culture influence the

business model in a foreign market for an interna-

tional retailer?

2. How should an international retailer analyze the host

culture of a foreign market?

Middle Class in China”—the research reveals that Home

Depot did not overcome significant challenges in China,

especially in its cultural understanding of the Chinese

market. Its “Do-It-Yourself” (DIY) business model, bor-

rowed from the US market, did not work in China.

Home Depot and Its Market in China

The Chinese government’s reform and deregulation of

the housing system led to a sharp increase in private

home ownership, which grew from almost nonexistent in

the 1990s to 90% today, far exceeding the global average

of about 60%, according to the China Household Finance

Survey Report jointly issued by Southwestern University of

Finance and Economics and the People’s Bank of China

(China’s reserve bank) on March 13, 2012. However,

these data may be inflated due to the fact that the survey

was not done by independent sources. China’s urban

households owned over 1.2 homes on average in 2011, a

substantial increase from over 0.7 homes in 2010, accord-

ing to statistics from China International Capital Cor-

poration. Li Daokui, a professor at Tsinghua University,

said that the survey results do not contradict the strong

demand for homes: “Many young people have left their

hometowns for other cities, which causes strong housing

demand,” Li explained (Fan, 2012).

The rise in people’s income level and purchasing

power, along with mortgage incentives and property

investment potentials, fueled private home ownership in

China. In March 2007, the National People’s Congress

strengthened this trend by enacting China’s first law to

protect private property (Flanagan, 2011). As a result,

China has been the world’s largest building material mar-

ket, both in production and in sales in recent years. It is

estimated that the production of China’s building mate-

rial industry would surpass 1,000 billion yuan

1

annually.

The Chinese market has attracted home improvement

retailers such as B&Q, IKEA, and Home Depot. The B&Q

chain, owned by UK-based Kingfisher PLC, the largest

big-box retailer in Europe, has been growing rapidly in

China since 1999. It has 58 stores in 25 Chinese cities,

from Shenzhen in the south to Harbin in the north.

Rising home ownership fuels the growth of the home

improvement market. In addition, most new Chinese

homeowners must do home renovation because the

homes they purchase are usually concrete shells. Since

the 1990s, the rapidly changing tastes of style in home

décor by Chinese homeowners led to a collective decision

on the part of home builders that they would leave homes

in urban China as empty shells so that home owners can

satisfy their own preferences. Homeowners of a typical

Culture Determines Business Models: Analyzing Home Depot’s Failure Case in China for International Retailers from a Communication Perspective

177

DOI: 10.1002/tie Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013

retailers entering emerging markets. Thus, a study of the

Home Depot China case can provide a useful lesson for

other international retailers planning to enter China or

other foreign markets. The single-case-study approach

has been applied in retail internationalization literature,

and it has enabled various researchers to provide impor-

tant new insights into the field (Palmer & Quinn, 2007;

Sparks, 2008). Additionally, exploratory methods such as

case studies have been recognized as being particularly

useful for examining strategies in emerging markets

(Hoskisson et al., 2000).

From 2006 to 2011, a total of 37 interviews were con-

ducted with Home Depot’s executives, lawyers, store man-

agers, employees, consumers, suppliers, and competitors.

The author visited Home Depot stores in China multiple

times, and witnessed its ups and downs from 2008 to

2011. A grounded-theory influenced approach was used

(Glaser & Strauss, 1967), which meant the research was

not limited by a priori hypotheses. Please see the list of

key persons interviewed for this research in Table 1. The

interviews were guided by, but not confined to, a list of

topics and themes derived from Reid and Walsh’s (2003)

model of strategic management:

• Company information

• Corporate positioning (product, service, strategic

partnership, advertisement)

• Product management strategy

• Market trends

• Competition

• Review of relative competencies

• Cultural trend of Chinese consumers

• External factors impacting the progress

• Advice for others

3. In what specific ways should an international retailer

such as Home Depot adapt its business model to the

Chinese market?

Research Method

The research method for this article is a longitudinal study

of a single case, with in-depth interviews and systematic

observation. The failure of Home Depot in China serves

as a good case for the analysis of international retailers’

choice of business model in a foreign market. The research

method was qualitative, and the inquiry was guided by the

search for “why” rather than “what” (Lindlof & Taylor,

2002) in regards to the effectiveness of a business model’s

fitness with the target consumers in a host culture.

Given the relatively unexplored nature of the

research topic of host culture analysis for a business

model in China for international retailers, this study

adopted an exploratory qualitative research strategy. Case

study methodology was used to assess the challenges and

opportunities of a home improvement retailer in China.

Yin (2003) suggests that case studies are epistemologi-

cally justifiable when research questions focus on reasons

behind observed phenomena, when behavioral events

are not controlled, and when the emphasis is on con-

temporary events. Case studies in organizational research

are suited to illustrate and examine research frame-

works, particularly in differentiated or unique instances

(Eisenhardt, 1989, 1991). The case study methodology

employed in this research has long been established as

a valid tool of mainstream academic inquiry, with par-

ticular support for its utilization in international business

research (Ghauri, 2004). Circumstances indicate that a

case research approach is appropriate when the com-

plexity of situations necessitates researchers to examine

a case in its entirety (Flyvbjerg, 2004). A single case such

as Home Depot in China is appropriate for the discovery

of new theoretical relationships for international retailers

entering a foreign market.

Reid and Walsh (2003) state: “In seeking to under-

stand international business, it is essential to understand

the countries involved and the particular local market

conditions prevailing. This is best achieved by conduct-

ing personal, in-depth interviews with leading executives

engaged with international businesses” (p. 294). From

in-depth interviews, abundant information can be gained

for this type of exploratory and inductive studies (Palmer

& Quinn, 2005). Case-based research requires a sampling

approach focusing on theoretically useful cases (Eisen-

hardt, 1989; Teagarden et al., 1995). The struggle Home

Depot faced in China is common for many international

The struggle Home Depot

faced in China is common

for many international

retailers entering emerging

markets.

178

FEATURE ARTICLE

Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013 DOI: 10.1002/tie

2011). This section uses Home Depot as an example to

illustrate international retailers’ target market in China.

Research shows that the Chinese population can be

categorized into four areas: (1) urban population in first-

and second-tier cities, (2) suburban population in first-

and second-tier cities, (3) population in third-tier cities,

and (4) population in rural areas. These four categories

take into consideration people’s income, education, pro-

fession, and lifestyle (Torres, 2011). The interview data

shows that Home Depot’s target market should have been

the urban middle class in first- and second-tier cities.

Why Should International Retailers Ignore Suburban

and Rural Customers for the Moment?

The research data shows that Home Depot can ignore the

rural and suburban population in China as its customers,

and needs to open stores in downtown areas for its target

customers—the urban population in first- and second-tier

Research findings are generated from analyzing the

patterns of 500+ pages of interview transcripts and field

notes. The interpretation of the data was triangulated

with secondary data and institutional analysis.

An International Retailer’s Target

Market in China

Market segmentation is usually defined as the process

of dividing potential customers into distinct groups for

the purpose of targeting and designing segment–specific

marketing strategies. A market strategy for China or any

other foreign market must begin with an understanding

of the cultures of the target market (Park & Sternquist,

2007).

The first priority of an international retailer in a for-

eign country is to identify segments for which an effective

marketing program can be developed (Xu & Greenwood,

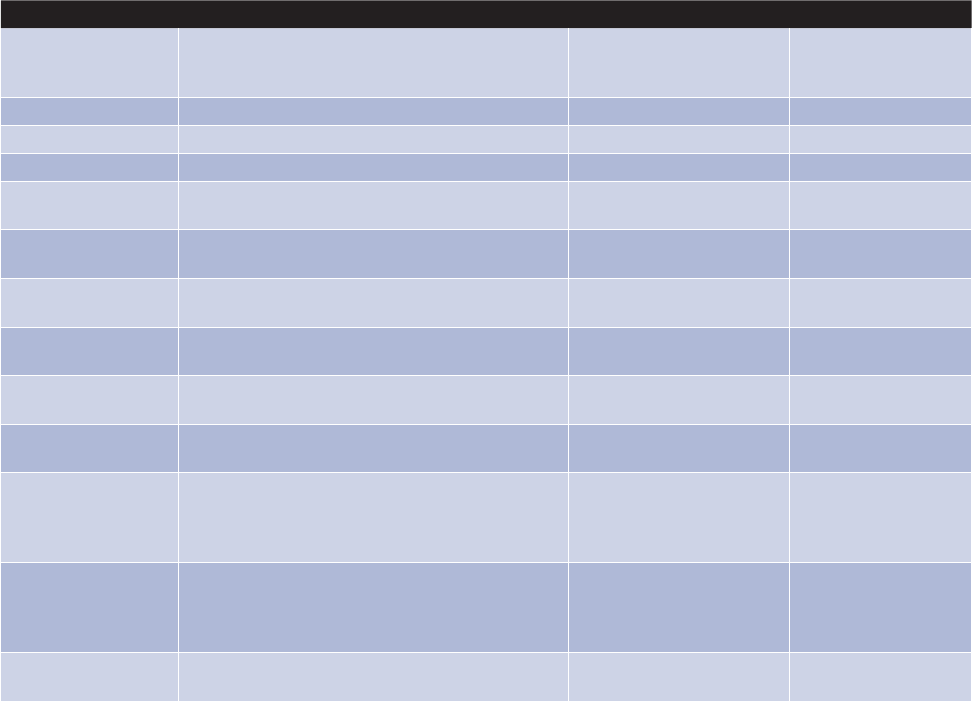

TABLE 1 List of Key Interviewees for This Research

Interview Totals: 37 Position Time of Interview Location of Interview

3 Attorney, Home Depot (China) July 2009

July 2010

July 2011

Beijing/Shanghai

1 Vice President, Home Depot USA November 2006 Atlanta

2 Store Manager, Home Depot China August 2010 Beijing

2 Store Manager, Home Depot China August 2010 Xi’an

5 Home Depot China employee July 2009

August 2010

Beijing

Xi’an

2 B&Q Manager July 2009

August 2010

Beijing

2 IKEA China Manager July 2009

August 2010

Beijing

2 Chinese Red Star Chain Manager July 2009

August 2010

Beijing

2 Store owners at Traditional Chinese Flower & Bird Market July 2009

August 2010

Beijing, Hefei, Yangzhou,

Shanghai

2 Construction Material suppliers July 2009

August 2010

Beijing, Hefei, Shanghai

5 Chinese customers who frequently visit Home Depot July 2008

July 2009

July 2010

July 2011

Beijing, Xi’an

5 Chinese customers who frequently visit Home Depot

competitors such as B&Q, Red Star, etc.

July 2008

July 2009

July 2010

July 2011

Beijing, Shanghai, Hefei

4 Chinese contractors/construction company managers August 2009

August 2010

Beijing, Hefei, Shanghai

Culture Determines Business Models: Analyzing Home Depot’s Failure Case in China for International Retailers from a Communication Perspective

179

DOI: 10.1002/tie Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013

Why Should International Retailers Target the Middle

Class in Top-Tier Cities?

Who are the target customers for Home Depot? The

interview data reveal that target customers for interna-

tional retailers such as Home Depot are the new-gener-

ation urban dwellers in first- and second-tier cities—the

“Zhong Chan ( )” class or “middle class.” China’s

middle class is larger than the entire population of the

United States and is expected to reach 800 million by

2025 (Chao, 2010; Wang, 2011). There is evident wealth

in the growing Chinese middle class. Interview data

indicates that Home Depot’s target market segment is

“Chinese customers aged from 20 to 45 in urban China.”

These consumers are price conscious, but demand high-

quality products and services.

The Chinese middle class consumers are fond of

Western name brands and luxury products. The “Luxury

Goods Worldwide Market Study” by Bain & Company

(2011) shows that global luxury sales grew 8% in 2011

to 185 billion euros, with China overtaking Japan as the

world’s second-largest consumer market of luxury goods,

only after the United States. The Boston Consulting

Group’s 2009 study reports that China is expected to

become the world’s largest luxury goods market in 2015,

accounting for 32.0% of the global market.

Some American companies try to connect their

products with the luxury concept. In 2009, Levi Strauss &

Co. launched a new brand in China tailoring to Chinese

tastes. Models were wearing high-heels instead of cowboy

boots. The newest Levis jeans, which sell for more than

US$100, are available in the upscale malls along Shang-

hai’s Nanjing Road shopping strip (Debnam & Svinos,

2011). Interview data suggests that Home Depot should

have redesigned its image and packaged its products and

services that carry the cache of “luxury from America.”

The new generation of Chinese consumers desire

status, and they are unabashed about flaunting their new

wealth as the “nouveau riche.” With a traditional focus

on “face” (reputation and status) in Chinese culture,

coupled with a growing amount of disposable income,

the new generation of Chinese middle class aspires to

conspicuous consumption. The Chinese middle class in

first and second tier cities is the target customer group

for international retailers in China.

Why Should International Retailers Target

Contractors?

Other than targeting middle-class consumers in top tier

Chinese cities, Home Depot should have tried to sell

to contractors, because many Chinese consumers hire

cities. Contrary to the United States, where the well-to-do

live in the suburbs, most of the Chinese well-to-do live

downtown. Despite the fact that home ownership in the

rural areas is 95% based on a 2012 survey (Fan, 2012),

international retailers such as Home Depot will not focus

on rural China in the current economic situation.

First, there is a greater urban population than rural

population in China. In 2011, China’s urban population

surpassed that of rural areas for the first time. There are

now over 690.79 million people living in urban areas,

compared with 656.56 million in the countryside, the

National Bureau of Statistics said in Beijing. The Chinese

urban population now doubles the total US population

(Rong & Zheng, 2012).

Second, urban dwellers have more disposable income,

as compared to suburban dwellers and the rural popula-

tion. On the one hand, contrary to American markets, the

Chinese suburban dwellers are not the well-to-do. In 2006

the income gap ratio in China between urban and subur-

ban residents reached about 3.3:1 (Chen & Wu, 2007).

On the other hand, income for China’s city dwellers more

than triples that of rural residents. Based on National

Bureau of Statistics of China data, in 2011, per capita dis-

posable annual income was 21,810 yuan for urban house-

holds, and only 6,977 yuan for rural households (Rong &

Zheng, 2012). “I am afraid the (urban-rural) income gap

will continue to expand as the country focuses its efforts

on urban sprawl, rather than rural development,” said

Song Hongyuan, director of the Research Center for the

Rural Economy in the Ministry of Agriculture (Fu, 2010).

International retailers such as Home Depot should focus

on the urban population as its target market, which is

twice as large as the US population.

International retailers such

as Home Depot should focus

on the urban population as

its target market, which is

twice as large as the US

population.

180

FEATURE ARTICLE

Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013 DOI: 10.1002/tie

However, Torres’s eight elements are repetitive in nature

and not well defined.

This research was approached with a theoretical

foundation incorporating various communication the-

ories applied to the international business context,

including Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions, Hall’s

context analysis, Ting-Toomey’s Face Negotiation argu-

ment, Schulster’s task-relationship dichotomy, and Fons

Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner’s cultural

orientation. Gao and Prime’s (2010) American-Chinese

Communication Facilitators and Obstacles framework

was referenced. Unfortunately, very few case studies have

been conducted to introduce a host culture analysis

framework. This interviews-based case study approach

adds new insights not currently available in the current

literature. From this research, a new framework of CELM

(Culture-Environment-Lifestyle-Mentality) for analyzing

host-country consumer culture was developed.

The 2012 Ernst & Young study identifies a key area

that will determine the success of companies in imple-

menting “innovations with minimum resources”—adapt-

ing to local consumer specifics. Companies will have to

adapt to the culture and mind-set of consumers they

wish to target, catering to their specific needs. The 2012

Ernst & Young study concludes: “The key to success will

be with those companies that know how to combine

local relevance with global presence, making sure that

their products and services are relevant for the local con-

sumer, while also enabling the company to benefit from

its global resources.” Gandolfi and Strach (2009) studied

the Walmart failure case in South Korea, and stated:

“The most important aspect for firms going global is an

in-depth understanding of what the local customers really

want, desire and need” (p. 195).

This article will analyze Home Depot’s challenge

in China from four dimensions: Culture, Business Envi-

ronment, Lifestyle, and Mentality. This article proposes

that CELM (culture, environment, lifestyle, mentality)

should be a cultural analysis framework for all inter-

national retailers entering foreign markets. The four-

dimensional cultural analysis framework is illustrated by

Figure 1.

Culture Determines Business Models

Osland (1990) states that the single greatest barrier to

business success is the one erected by culture. Interview

data shows that culture is a key determinant that influences

business models in a foreign market for an international

retailer. Lee (2000) states that culture is the way of life

of a people, and he stresses that theories of management

contractors to complete their home improvement jobs. As

a result of the 28th Meeting of the 8th National Congress,

Clause 24, s. 2, Ch. 3 of the Construction Law of China

encourages the procurement of construction projects

through design-and-build as a packaged deal ( ).

In a typical design-and-build project, prequalified design-

and-build contractors submit their tender documents

(including preliminary designs and cost estimates)

against the client’s requirements. Based on the evalu-

ation of the various bidders’ plan, one contractor is

selected (Xu & Greenwood, 2011). This contractor is

charged with purchasing construction materials, and

such contractors are an important segment of Home

Depot’s market in China.

Home Depot should have identified contractors as

a key segment of market in China. Li, a retired military

officer, was a regular customer at Home Depot. In 2010,

Li paid 6,000 yuan ($909) to the Home Depot Beijing

store for a bathtub and cupboard for her condo in Bei-

jing. She said she did not like Home Depot’s big-box

superstore culture. “I think most Chinese prefer hiring a

decoration company rather than going the do-it-yourself

way … and shopping assistants here are not enthusiastic

about giving advice as I need help to understand the

differences among various brands. Most shop assistants

only promote the brands that they are paid to represent.”

An interview with a Home Depot store manager indi-

cates that there were two types of salespeople wearing

the orange Home Depot aprons in the stores in China:

the first group (with orange straps) were Home Depot

employees; and the second group (with black straps)

were salespeople hired by certain brands. The second

group, who are the “shopping assistants” mentioned by

customer Li, were actually paid sales reps for certain

brands; of course, they were not helpful in explaining

other brands to the customers. Home Depot China could

have paid more attention to contractors as representa-

tives for the middle-class homeowners.

CELM—A Four-Dimension Host

Country Culture Analysis Model

for International Retailers

Torres (2011) suggested a Chinese cultural and philo-

sophical framework for developing marketing strategies

and research that includes eight elements: (1) culture

definitions, (2) cultural dimensions, (3) cultural dynam-

ics, (4) emotional intelligence, (5) cultural intelligence,

(6) country-specific culture and philosophy, (7) Chinese

communication, and (8) Chinese culture and philosophy.

Culture Determines Business Models: Analyzing Home Depot’s Failure Case in China for International Retailers from a Communication Perspective

181

DOI: 10.1002/tie Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013

Hofstede et al., 2010). In order to prosper in China,

international retailers such as Home Depot need to

adjust their business models to the culture of the Chinese

consumers. Home Depot’s DIY model, which requires

consumers to labor on the projects themselves, is compat-

ible with American culture. However, the interview data

and field notes show that the DIY model is not compat-

ible with the Chinese culture. Most Chinese homes are

condominiums with no garages and limited space to store

tools; labor is inexpensive in China; and for thousands of

years, manual labor has been looked down upon in the

Confucian tradition.

To succeed in China, international retailers need

to reposition themselves and redesign their business

models. National cultures determine business models,

and regional subcultures further refine business mod-

els. “While America is a big country, 95% of what the

standard home-improvement store in Texas and in

Alaska offer is similar. That’s not true in China. Tsingtao

(Northeastern China) and Shenzhen (Southern China)

might as well be in different countries,” said Mr. Sli-

winski, CEO of B&Q, a top British home improvement

retailer. Mr. Sliwinski told the researcher that B&Q

in Northern China sell lots of carpeting and wooden

flooring while homeowners in Southern China prefer

tile or marble due to the heat and humidity. Ovens are

for sale in Beijing (Northern China) but not in Kun-

ming (Southern China). China’s vast income disparities

and regional differences indicate that a one-size-fits-all

approach to home improvement does not work. B&Q

also adjusted its prices for the same product and service

in different cities. In Shanghai it charges up to 100,000

yuan for a fully designed apartment, including all the

materials. In second-tier cities such as Chongqing, a city

with 35 million people, B&Q offers a similar deal for

less than 50,000 yuan. Customers receive a money-back

guarantee that the products are authentic and the work

is done right, no matter what price they have paid. Local

culture determines business models for an international

retailer.

Business Environment

In a crowded bustling marketplace with competition from

domestic and foreign companies, Chinese consumers live

in an environment where countless choices of products

and services are available within close reach. The research

data shows that the unique Chinese business environment

features changing rules and regulations, under-the-table

kickbacks, and different methods of business operation.

Being successful in the US market does not guarantee

that an American retailer will be successful in China.

and marketing are culture bound (Hofstede, 1993).

The fundamental marketing concept refers to the philo-

sophical conviction that customer satisfaction is the key

to achieving organizational goals. When customers in a

foreign culture have different needs, marketers have to

come up with different product and service offerings.

Interview data shows that Home Depot miscalculated its

target market, and misunderstood its customers in China.

The research findings suggest that host-country culture

is a determinant in the choice of business models for

international retailers in China. A culture is a group’s

“shared software of the mind” (values, traditions, social

and political relationships, history, language, etc.) based

on a collection of symbols used to interpret the meaning

of nature, human life, and the environment (Gao, 2005;

FIGURE 1 Host Culture CELM Analysis Model

When customers in a foreign

culture have different needs,

marketers have to come up

with different product and

service offerings.

182

FEATURE ARTICLE

Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013 DOI: 10.1002/tie

Fourth, middle-class Chinese customers usually live

in downtown areas in metropolitan Chinese cities. Dif-

ferent from the United States, in China, proximity of

one’s home to downtown adds to home value. However,

based on Home Depot’s DIY model borrowed from the

United States, Home Depot stores were located mostly in

the suburbs, not in downtown. In Beijing, a city with 17

million people, B&Q has six stores, and Home Depot had

only one functional store in 2010 (this store was closed in

January 2011). The store was on the fourth ring road, far

away from the downtown, hidden behind trees. To drive

from one end of the city to the other usually takes two to

three hours in Beijing. Who would like to take a taxi for

two to three hours to this one Home Depot store to buy

a lightbulb?

With such a limited number of stores (12 stores in

four cities in 2006 and then 7 stores in three cities in 2011,

and now all closed), the percentage of market share for

Home Depot in China was negligible. As a result, suppli-

ers were unwilling to strike deals, and thus Home Depot

prices were not competitive for price-conscious Chinese

customers. Many Chinese suppliers were aware of the fact

that Home Depot was a Fortune 500 company, but when

they compared Home Depot to its foreign and Chinese

competitors in China regarding sales volume, they chose

not to favor Home Depot. Suppliers in China jokingly

compared Home Depot China to a thin chicken wing: “to

eat it, it is tasteless; to abandon it, it is pitiful.”

Finally, labor is cheap in China. In a nation with a

sizable pool of unskilled labor and countless small-time

construction companies, it is simply more convenient

and cheaper to outsource such manual labor jobs as

home improvement. As a result, most Chinese consumers

do not Do-It-Themselves on home improvement. They

choose to hire contractors.

Target Consumer Lifestyle

A 2012 Ernst & Young study indicates that companies will

have to adapt their development strategies to answer to

the new demands of the middle-class rapidly growing at

a global level, especially in emerging markets. Changes

will have to include the development of brand new prod-

ucts and services, if these companies are willing to com-

mit to achieving true innovation and to obtain growth.

This study by Ernst & Young includes a survey with 547

executives all over the world, as well as in-depth inter-

views with influential global entrepreneurs. The study

emphasizes the fact that most companies in developed

economies are now focusing their efforts and actions on

the high-end segment of the market. Even in the case of

companies in emerging markets, high-end segment sales

First, homes purchased in Chinese cities are primarily

unfinished condos, and need to be completed by profes-

sionals, as a comprehensive project. Managers at B&Q in

China rarely talk about the DIY model, because much of

what customers do in China is to pay contractors for the

fix-up work (Desvaux & Ramsay, 2006). Most customers

do not do it themselves in terms of shopping for building

materials and fixing up the condos.

Second, the Chinese home-improvement market is

heavily fragmented. Home Depot specializes in build-

ing materials, home improvement supplies, and lawn

and garden products. However, the playing field in

the home improvement market is not level. The mar-

ket system is chaotic at the moment, to say the least.

Chen, a store manager of Home Depot China, says that

this market is currently a “blind spot” for any foreign

retailer and that nobody knows the rules of the game.

B&Q, the No. 1 foreign retailer, is no exception. The

top three home improvement companies combined

occupy only 3% of the total Chinese home improve-

ment market, making the rest up for grabs (Moody,

2009). Numerous small-scale Chinese manufacturers

and retailers, who rent buildings from developers in

edge-of-city retail developments, dominate the Chinese

home improvement market. These retail developments

tend to have one floor for lighting, one for flooring,

one for furniture, one for paint, and another for drap-

ery. “Many of these used to ship all their stuff off to the

West to the likes of Home Depot but now they just open

up relatively inexpensive shops in Nanjing, Shanghai or

Hangzhou. They put three guys in there on minimum

salary and they get all the margin, both wholesale and

retail,” said Tong at Roland Berger Strategy Consultants

(Moody, 2009).

Third, there are many “gray areas” of doing business

in China. As a US company bound by US laws, Home

Depot cannot utilize the “gray channels” that Chinese

firms use to secure government or business favors by pay-

ing them with fat gifts and commissions. In addition, in

Chinese home improvement stores, the price of virtually

everything is up for negotiation between the seller and

buyer on the spot, similar to a flea market. Various makes

of tiles and bathtubs, after negotiation and payment,

will be delivered for free to customers’ homes (Schmitz,

2011). Most Chinese homeowners hire designers to

shop for building materials. When designers buy tiles

from a Chinese home improvement store, they receive

cash bonuses on the spot. This is the system that Home

Depot is up against in China, where business depends on

“guanxi” (long-term reciprocal connections, ) and

under-the-table commissions.

Culture Determines Business Models: Analyzing Home Depot’s Failure Case in China for International Retailers from a Communication Perspective

183

DOI: 10.1002/tie Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013

of them get the down payments from their parents. Most

Chinese parents are willing to spend their lifelong savings

securing a home for their only son or daughter, because

the one-child policy has put the only child at the center of

the Chinese family structure. “It is almost impossible for

me to buy a home without the support from family,” Mr.

Zhu, a young groom-to-be, told the researcher.

For the Chinese people, the word “home” repre-

sents not only “a place to live in,” but also a precondi-

tion of marriage, a badge of social status, and a sense of

security. A 2010 survey indicates that 60% of the young

homeowners buy their homes in order to get married.

A total of 64% of the respondents agree that there is a

direct relationship between owning a home and a happy

life. In China, pressure to buy a home also comes from

parents and other family members. For example, 70% of

the parents would mind if their daughters’ future hus-

bands do not own a home; while 50% of the parents with

a son express a positive attitude in helping their sons

to buy a home before marriage. Some young couples

even delay their marriages due to an inability to buy a

house (Jin, 2010). Renting an apartment is possible, but

it is not a sign of success for a couple to settle down in

China.

“Naked marriage (

)” is a new concept created

by the post-1980s generation in China. Naked marriage

means a couple marrying without a house, a car, a wed-

ding, and even a honeymoon. However, males and females

hold distinctive attitudes toward “naked marriage” in

China. An online survey indicates that 80% of the male

respondents are in favor of “naked marriage,” while 70%

of their female counterparts regard “naked marriage” as

“absolutely infeasible” (Jin, 2010). Apparently, the concept

of “naked marriage” is not popular in China with women,

and therefore home ownership is still critical for young

couples, especially among the middle class.

Yu, a 40-year-old construction contractor, said: “All

my customers are designers. I never talk to homeown-

ers. Homeowners in China hire designers for all their

home improvement projects, helping the decision of

even where to put a vase.” In other words, many middle

class homeowners in China will not come to Home Depot

personally to shop for building materials, a fact that rein-

forces that the DIY business model is not compatible with

the lifestyle of the target customer in China.

In summary, the lifestyle of the Only Child genera-

tion of the middle class does not support a DIY business

model for Home Depot. These only children are usually

not hands on, and they have the disposable cash to hire

others to complete the home improvements, including

building, designing, and even purchasing.

share amounts to 40% (Ernst & Young, 2012). Similarly,

the interview data revealed that the target customers of

international retailers such as Home Depot in China are

middle-class homeowners in top-tier cities. The lifestyle

of this group of urban dwellers needs to be analyzed. A

person’s lifestyle is indicated by how he/she spends time

and resources and what he/she considers important. The

analysis of target consumer lifestyle helps to distribute

products and services (Strategic Business Insights, 2011).

In 1975, China adopted the “One Child Policy” as a

national regulation for population control, with urban

dwellers allowed only one child per couple. These only

children, the “little emperors and empresses” of China,

are now in their 20s, 30s, and approaching their 40s. They

are the vital components of international retailers’ target

consumers in China. Most of these only children become

homeowners when they get married, usually with finan-

cial contributions from their parents. These only children

have been somewhat spoiled by their two parents and

four grandparents, and have normally not done much

manual labor work growing up in urban China. The

research data shows that Home Depot’s DIY model does

not seem to be suitable to this group of key customers.

In 2010, China Ever-bright Bank and the Beijing-

headquartered real-estate corporation Homelink jointly

published an analytical report, indicating that the average

age of people in Beijing who buy their first homes on a

housing loan is 27, which is much lower than that in most

developed countries (42 in Japan and Germany, 30 in

the United States). Ninety percent of the young people

in China buy their homes with a mortgage loan and most

Changes will have to include

the development of brand

new products and services, if

these companies are willing

to commit to achieving true

innovation and to obtain

growth.

184

FEATURE ARTICLE

Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013 DOI: 10.1002/tie

However, Home Depot as a brand was basically unknown

in China. Visiting China in August 2010, the author had

great difficulty finding the Home Depot store in Beijing,

and most taxi drivers had never heard of Home Depot.

Third, the middle class is price savvy. A typical Chinese

consumer practices comparative shopping, rather than

impulsive buying. A popular Chinese saying goes: “Never

make a purchase until you have compared three shops

(

)” (Letovsky et. al, 1997). Inaugurating its

first Chinese store in Shanghai in 1999, B&Q soon real-

ized that a cookie-cutter version of its British stores did

not work in China. Chinese shoppers, who like to handle

the merchandise before buying, were frustrated that prod-

ucts were stacked high on shelves. Many never ventured

far into the store at all because they were intimidated

by the prices of the most expensive goods at the head of

each aisle. B&Q then changed the display of goods; now

everything is within easy reach, and the bargains are front

and center (Bloomberg Business Week, 2006). Zhan, a home-

owner who had lived and worked in the United States and

who had been to Home Depots in both countries, told the

researcher that compared to its Chinese competitors, the

Home Depot in China price point was a serious problem.

Ms. Wu recently fixed up a new condo home for her par-

ents, who moved to the capital in June 2010. She said she

had never heard of Home Depot, even though there was

one a mere five-minute drive from her home. She chose to

turn to a local contractor to remodel the apartment after

comparing B&Q with Chinese companies. “I tried shop-

ping there [B&Q] once, but I felt there were more choices

at eHome [a Chinese competitor] and that it was cheaper

… I could bargain there,” she said.

In summary, Chinese consumers now have access

to well-known brands and are willing to spend more

for better-quality products. International retailers need

to take advantage of this trend and to promote their

store brands, as well as to keep their merchandise price

competitive. To understand the four dimensions of host

culture in the Chinese market is critical for the success of

market development strategy for international retailers,

including the understanding of the Chinese culture, Chi-

nese business environment, and Chinese target consum-

ers’ lifestyle and mentality.

DIFM—The New Business Model

for Home Depot and Other

International Retailers

Gandolfi and Strach (2009) analyzed Walmart’s failure

case in South Korea, and concluded that Walmart’s busi-

ness model of “Every Day Low Prices” did not work in

Consumer Mentality

Mentalities provide all-embracing explanations of pur-

pose in collective human activities. The mentality of the

Chinese middle class is the deciding factor for decoding

the behavior of target consumers for international retail-

ers such as Home Depot. This research shows that the

mentality of Chinese middle-class consumers does not

support Home Depot’s DIY business model.

First, there is a “social status issue” concerning the

DIY model. Since antiquity, manual labor has been looked

down upon in China. Only lower-class citizens have to deal

with manual labor. Mencius,

2

a major disciple of Confu-

cius, once said: “Those who work with their brain rule, and

those who work with their muscles are the ruled.” To be able to

avoid manual labor was a class symbol in ancient times,

and it continues to serve as a symbol of success for today’s

middle class in China. Tianjin, a 13-million-people port

city near Beijing, was a major hub for Home Depot at one

time, with four stores. One Home Depot store had a huge

paint counter near the entrance; stacks of lumber near the

exit; and aisles of screws, fixtures, and tools in between. It

looked exactly like a Home Depot in the United States,

and according to Zheng, a typical middle-class customer,

that was the problem: “Products are too cheap and simple

at Home Depot. Poor people are the only group in China

who would bother taking on a DIY project, because they

cannot afford to hire others.” However, poor people in

China live in rural areas and the suburbs, and they would

buy building materials from Chinese stores and second

hand markets, where products are much cheaper than

Home Depot. Further, many suburban and rural dwellers

do not own homes, or do not spend much money in reno-

vating their homes. In addition, many rural homeowners

are migration workers

3

in urban construction fields. Some

of these migrant workers receive building materials torn

down from old buildings as partial reward for their labor.

They do not need to purchase from expensive interna-

tional retailers such as Home Depot.

Second, the Chinese middle class is brand conscious.

A brand brings a wealth of quality, value, and high-perfor-

mance cues. Sparks (2008) and Kim (2009) found that the

Chinese people are very brand conscious, and view West-

ern brands as the embodiment of quality and authenticity.

Research conducted by Accenture (2011) indicates that the

purchasing behavior of Chinese consumers is influenced

by the brand’s national origin. American brands, such

as Starbucks, Pizza Hut, and Häagen-Dazs, are associated

with the luxury lifestyle portrayed in Hollywood movies. In

addition, consumers in China tend to trust Western brands

more because there are so many counterfeits in China.

Culture Determines Business Models: Analyzing Home Depot’s Failure Case in China for International Retailers from a Communication Perspective

185

DOI: 10.1002/tie Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013

(2) competition from Chinese companies, foreign com-

panies, and “Chinese traditional flower and bird mar-

kets”

4

eroding Home Depot’s market; and (3) the

inability of Home Depot to adapt to its Chinese consum-

ers; (4) the brand name of Home Depot was little known

by Chinese consumers.

The research data shows that Home Depot’s DIY

Model does not work for China. Does this mean inter-

national retailers such as Home Depot should give up

the Chinese market? An old Chinese saying translates:

“Failure is the mother of success.” If international retail-

ers learn from their failures and create new business

models, then the Chinese market can be profitable. Since

the Chinese consumer market is new and still emerging,

companies have an opportunity to rebrand their products

and services with new business models. The research data

suggests that Home Depot should have replaced its DIY

model with a DIFM (Do-It-for-Me) Model.

To Adopt the DIFM Business Model

From 2006 to 2012, Home Depot applied its Ameri-

can DIY business model almost without modification

to China: its stores were operated on a big-box format

located mostly at the outskirts of Chinese cities; its display

of store merchandise required customers with substantial

knowledge for self-work; and its advertising format was

mailing printed flyers to customers. The interview data

indicates that Home Depot misread its consumers when

applying its DIY model to China. Some managers in

Home Depot hold the illusion that Chinese consumers

“will catch up” with the idea of Do-It-Yourself, even after

they discovered DIY did not work for China. Based on the

four-dimensional CELM analysis of the Chinese culture,

this research suggests that Home Depot should replace

the DIY Model in China with the DIFM business model.

The interview data shows that Chinese middle-class

consumers simply do not want to “do it themselves.” They

want to hire others to complete their home improvement

projects. The more practical Chinese business model

for Home Depot is DIFM. DIFM is a customer-centered

business model that combines products with services. In

the DIFM model, Home Depot would provide “design

and build service” in a package to customers, and the

company would establish long-term relationships with

consumers, contractors, and suppliers. The only major

task the Chinese customer would need to do is to discuss

with the Home Depot team what they want as the end

product package.

Home ownership was almost nonexistent about 15

years ago in China. It was then very common for a family,

sometimes three generations, to share a 300-square-foot

the South Korea market. Walmart failed in South Korea

primarily due to its inability to understand the shopping

preferences of local consumers. Similar to Walmart’s

failure in South Korea, interview data shows that Home

Depot’s DIY business model did not work in China.

The findings from this research are consistent with the

cultural adaptation perspective on global market expan-

sion for international retailers. Reid and Walsh (2003)

indicate that business models that have achieved success

elsewhere almost invariably must be repositioned for the

China market.

Previous research has stressed the importance of the

learning process for retail internationalization (Palmer

& Quinn, 2005). A study by Davies and Sanghavi (1995)

illustrated how market innovation helped the retailer

Toys “R” Us overcome barriers and become successful in

Japan. Retailing research suggests that it is important not

only to understand environmental differences, but also

to adapt properly to new cultural conditions (Dupuis &

Prime, 1996).

Home Depot underperformed in China and has

closed all of its 12 stores. Interviews with Home Depot’s

store managers and former attorneys revealed obvious

problems with Home Depot’s operations in China:

(1)poor margins on high-volume items affecting profit;

Chinese consumers now have

access to well-known brands

and are willing to spend

more for better-quality prod-

ucts. International retailers

need to take advantage of

this trend and to promote

their store brands, as well

as to keep their merchandise

price competitive.

186

FEATURE ARTICLE

Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013 DOI: 10.1002/tie

Home Depot was once experienced in design cen-

ters. In 1991, Home Depot established its first Expo

Design Center in San Diego. The Expo Design Centers

carried higher-end products and sold complete solutions

to household needs, such as modular kitchens, assembled

bathrooms, etc. In the mid-1990s, Home Depot collabo-

rated with the Discovery Channel and Lynette Jennings

on a home improvement program, called HouseSmart,

which was televised daily (ICMR, 2004). Companies

that invest in educating the market can expect to reap

handsome rewards. An international retailer such as

Home Depot can consider collaborating with a Chinese

television station and creating an educational home

improvement TV show to educate Chinese consumers. In

addition, such TV shows will simultaneously promote the

Home Depot brand.

From Big-Box Retailing to “Urban Boutique Store”

Format

Big-box retail stores have been icons of urban sprawl

in the United States. Because of their large footprints

big-box retailers usually choose to locate in suburbs.

Research data shows that a suburban location choice

moves the economic activities away from the urban core

of middle-class consumers in China. Chinese consumers

are keen on exploring foreign brands if the products

are readily accessible. In addition, Chinese customers do

not like to buy all their home-improvement products in

a one-stop shop. To ensure that the products are within

close proximity to consumers, the research data indicates

that Home Depot should adopt the next generation store

concept—urban boutique stores (UBS).

First, in terms of location, UBS stores can be placed

in malls, street corners, or other pedestrian-heavy areas

in downtown Chinese cities. “Mall culture” has arrived

in China, and shopping is increasingly being adopted

as a leisure activity (Debnam & Svinos, 2011). Smaller

boutique stores in downtown areas are more visible

than big-box stores in the suburbs of China. UBS stores

will also be accessible to Chinese shoppers via public

transportation, such as via subway, bus, taxi, and bike.

In 2011, ZARA HOME from Spain opened two stores

in downtown Beijing, targeting trendy customers and

home-decorating enthusiasts. The stores are located

in fashionable shopping areas and department stores.

Harbor House, an interior-decorating brand; MUJI, a

retailer of household goods; and HOLA Home Furnish-

ing Store are close neighbors. Their retail merchandise

includes things often seen in a Home Depot store: furni-

ture, home accessories, carpet, tableware, glassware, and

linen (Yao, 2011).

room. Today, Chinese homeowners are eager to learn

from the West about home improvement. This is one

reason why IKEA is popular in China. Their Western-style

showrooms provide model bedrooms, dining rooms, and

family rooms. IKEA’s stylish and functional modern fur-

niture is particularly appealing to young couples (Wang,

2011). CELM analysis of the Chinese consumer culture

demands that international retail stores such as Home

Depot demonstrate strong design capability. A design

center can function as an educational base for home

improvement to the new generation of Chinese home-

owners. In China, design services have boomed, account-

ing for one third of sales, and could provide a crucial

advantage to Home Depot (CNN, 2010). In Shanghai,

B&Q has developed a full-blown in-house design center.

Homeowners can sit down with an interior decorator

using a computer displaying three-dimensional images

of their apartment. The decorator then hires contractors

to install electrical outlets, bathroom plumbing, kitchen

appliances, flooring, and almost everything else. The only

requirement is that 80% of goods must be purchased

through B&Q. In 2006 the company outfitted 30,000

apartments in China. To figure out the ever-evolving taste

of Chinese consumers, B&Q relies on its 12,000 Chinese

employees for insight. Informal chats in the stores, as

well as staff meetings, help drive the latest intelligence up

to the head office. The centers also offer free bus rides

to B&Q stores in nearby cities so that customers can see

fully built models of kitchens and bathrooms. “This is the

first apartment they have owned,” Gliwinski says. “They

need advice, and they need imagination. You need to let

them see what a home looks like” (Warner, 2007). In a

B&Q store in Shanghai, customers take photographs of

the kitchen and bathroom mock-ups, jot down notes, and

make shopping lists.

Today, Chinese homeowners

are eager to learn from the

West about home improve-

ment. This is one reason why

IKEA is popular in China.

Culture Determines Business Models: Analyzing Home Depot’s Failure Case in China for International Retailers from a Communication Perspective

187

DOI: 10.1002/tie Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013

started to learn some interesting household consump-

tion patterns and the influence of women’s preferences.

For example, what comes with house purchases is always

furniture buying, and in China, it is mostly women who

furnish the house, regardless of who pays (Ni, 2012).

Therefore, furniture manufacturers and home improve-

ment retailers that cater to the tastes of female customers

may have a better opportunity to boost their sales. You

cannot ignore women in the home improvement busi-

ness. It is especially important that Home Depot consider

Chinese women as key purchasing agents. “Our main

customers are female, both young and mature. We not

only provide stylish decorating products, but also offer

customers interior decoration ideas as well as updates

on the latest trends and information in this field,” said

Inditex, the owner of ZARA stores. B&Q plans to open a

new generation of female-friendly stores, recognizing the

fact that women in China are often the key decision mak-

ers regarding home furnishing decisions (Moody, 2009).

Finally, many international retailers have shifted

from the big-box format to the UBS format. For example,

Best Buy decided to abandon the big-box business model

and, instead, expanded its Chinese subsidiary Five Star,

which is based more on a boutique store model. IKEA

is expected to open three regional shopping centers in

cities like Wuxi, Beijing, and Wuhan. In addition to IKEA

stores, the centers will have outlets for fashion, food,

home electronics, and entertainment.

To Focus on Strength

Home Depot can amplify its strength and develop toward

success. First, because of its successful business in the

United States, Canada, and Mexico, Home Depot has

established relationships with hundreds of suppliers in

China for its North American markets. Home Depot can

negotiate with these suppliers for its stores in China for a

favorable rate.

Second, Home Depot is a US-based Fortune 500

Company and should advertise its brand name as reli-

able, trustworthy, and representing a luxury lifestyle, as

portrayed in Hollywood movies. The company is known

to carry reliable products. For example, Home Depot

recently became the exclusive vendor of US-made Behr

paint. It’s a strategic move in a market where paint laden

with chemicals harmful to people’s health is the norm

(Schmitz, 2011). By selling environmentally friendly Behr

paint, Home Depot aligned its business with the Chinese

government’s priority of green technology. Chinese con-

sumer Qian said he came to Home Depot because he

trusted the materials there as safe and authentic. There’s

so much counterfeiting in China that people do take

Second, in terms of store appeal, a UBS store should

be fashionable, urban, technologically advanced, female

friendly, and service oriented. Home Depot would need

only to place samples of the building materials in its cozy

and chic UBS stores. In UBS, international retailers need

to create user-friendly software so that customers could

design their own condos on a laptop, iPad, or iPhone. In

other words, in addition to creating product differentia-

tion through pricing, international retailers should focus

on long-term technical and emotional benefits in China.

Further, based on the CELM analysis for Chinese con-

sumers’ lifestyle and mind-set, it seems to be a good idea

for international retailers to appeal to China’s nouveau

riche. International retailers such as Home Depot may

want to connect its brand name to a luxury lifestyle so

that to buy from Home Depot becomes a status symbol

in China. The connection between “American products”

and “luxury lifestyle” has been a recipe for success for

many international retailers in China.

Third, in UBS stores, female consumers shall be

emphasized. According to a 2008 survey by Pew Research

Center, women are key household decision makers in

North America and Asia. In 74% of homes, the woman

is fully engaged in deciding what and where to shop

(Mazurkiewicz, 2008). “The future is female,” HSBC said

in a 2010 survey on luxury goods, highlighting the impor-

tance of female consumers to the investment decision

making of many global companies (Ni, 2012). Departing

from a traditional thrifty lifestyle, middle-class women in

China are more prone to enlarge their expenditures and

lower their saving levels. The Women of China Magazine

research shows more than 60% of average household

income went into consumption in 2011. Businesses have

The connection between

“American products” and

“luxury lifestyle” has been a

recipe for success for many

international retailers in

China.

188

FEATURE ARTICLE

Thunderbird International Business Review Vol. 55, No. 2 March/April 2013 DOI: 10.1002/tie

International retailers should make every effort to foster

local partnerships.

American companies usually use actions of giving

back to the community through corporate social respon-

sibility (CSR) to gain support from the Chinese govern-

ment. Participating in earthquake relief and sponsoring

sports and educational events brought attention and sup-

port from the Chinese government and from consumers

to a foreign company and its brand. For a US company,

the alternative of such public CSR—bribery—is not an

option. The Anti-Corruption Act of the United States

obstructs any US company from using this method to

promote relationships with Chinese government officials.

Home Depot does have a set of core values developed in

the mid-1990s, and such CSR work can be very beneficial

to expand the Chinese market.

In summary, the new UBS stores will be boutique in

size, female friendly, trendy, chic, and appear at many

busy street corners to increase volume of sales. The

precondition before the massive promotional effort is

to increase market share by opening more stores on a

smaller scale on populous streets and near big subdivi-

sions. Perhaps Home Depot can become an Apple Store

experience with chic home improvement centers in Chi-

nese malls. Consumers will then choose a home design

on an iPad or a MacBook in such Home Depot design

stores. To buy from Home Depot could become a symbol

of social status in China under the UBS concept.

Conclusion and Discussions

This longitudinal case study of Home Depot’s operations

in China illustrates how an international retailer may

comfort in an overt guarantee of authenticity,” says Mur-

phy, the Kingfisher chief (Warner, 2007).

Third, Home Depot, as a US company, has a very

good return policy. Most Chinese competitors do not

have a comprehensive return policy, and Home Depot

should advertise this policy to Chinese consumers. How-

ever, the policy has to be well written so that customers

do not take advantage of it. For example, some Chinese

customers might buy a tool from Home Depot, use it, and

then return it for a full refund.

Fourth, Home Depot, being a top American com-

pany, carries the country of origin effect of being from

the United States. Research shows that the Chinese have

a very positive image of American products (Yang, 1998).

An international retailer from the United States can

promote the country of origin equity of its products and

store brand.

To Cultivate Local Partnerships

Entry-mode literature suggests that firms entering cultur-

ally distant markets are better off having a local partner

(Barkema, Bell, & Pennings, 1996). An IKEA manager

told the researcher that trust was very important in China

where personal relationships meant so much. The inter-

views show that managers in Home Depot China faced a

challenge in communicating with various departments

and with various levels of the Chinese government, as well

as with landlords for their stores. Interview data indicate

a common theme that in Home Depot’s China policies

and strategies, there is a lack of consistency, transparency,

and clarity.

While American business culture is typically transac-

tion based, the Chinese business culture is more relation-

ship based. Guanxi, the Chinese version of relationship,

is built upon a degree of trust, reciprocity, and long-term

commitment. A top executive of Coca-Cola University in

Shanghai told the researcher that, in China, local part-

nerships were crucial. “You really have to know whom

you are getting into business with,” he said. “People

with Chinese connections can do a lot. … Local market

expertise is critical. To be successful you can’t overlay

your US or Western European private equity experience

in these markets. If you have trustworthy local partners to

help you, that would be a good start.” In China, develop-

ing a good guanxi with the relevant organizations and

authorities can make a difference to the outcome of any

business endeavor. In China, people need to get to know

their business partners and to gain mutual trust before

any business is conducted. Guanxi with local partners,

such as government, landlord, suppliers, wholesalers,

and consumers, will lead the way toward business success.

The new UBS stores will

be boutique in size, female

friendly, trendy, chic, and

appear at many busy street