ACLU of Hawai‘i Decriminalizing Houselessness in Hawai‘i 1

DECRIMINALIZING

HOUSELESSNESS

IN HAWAI‘I

REPORT & RECOMMENDATIONS

ACLU of Hawai‘i Decriminalizing Houselessness in Hawai‘i 2

Decriminalizing Houselessness in Hawai‘i

Acknowledgements

Housing Not Handcuffs 2019: Ending the Criminalization of Homelessness in U.S. Cities

The Effects of City Sweeps and Sit-Lie Policies on Honolulu’s Houseless

Author Positionality Statement

Language In This Report

1

Methodology

Layout and design:

www.acluhi.org/criminalizationofhouselessnessreport.

Find out more information or contact us at:

ACLU of Hawai‘i

www.acluhi.org

acluhawaii

ACLU of Hawai‘i

The criminalization of houselessness is costing

the public. Millions of taxpayer dollars are spent

each year on police sweeps and other enforcement

actions that are wholly ineffective at reducing,

let alone ending, houselessness. Meanwhile,

there is an acute shortage of permanent housing

support—the top service need reported by

unhoused individuals. In relying on policing to

respond to houselessness, Hawai‘i policymakers

are missing an opportunity to use public

resources in ways that could meet the needs of

the unhoused, as well as those of the broader

community.

This report presents pathways for Hawai‘i

to decriminalize houselessness and invest in

solutions that promote racial equity. These

pathways are informed by interviews with service

providers, government officials, community

activists, and individuals who have experienced

houselessness, as well as from data and

documents acquired through Uniform Information

Practices Act (UIPA) Records Requests.

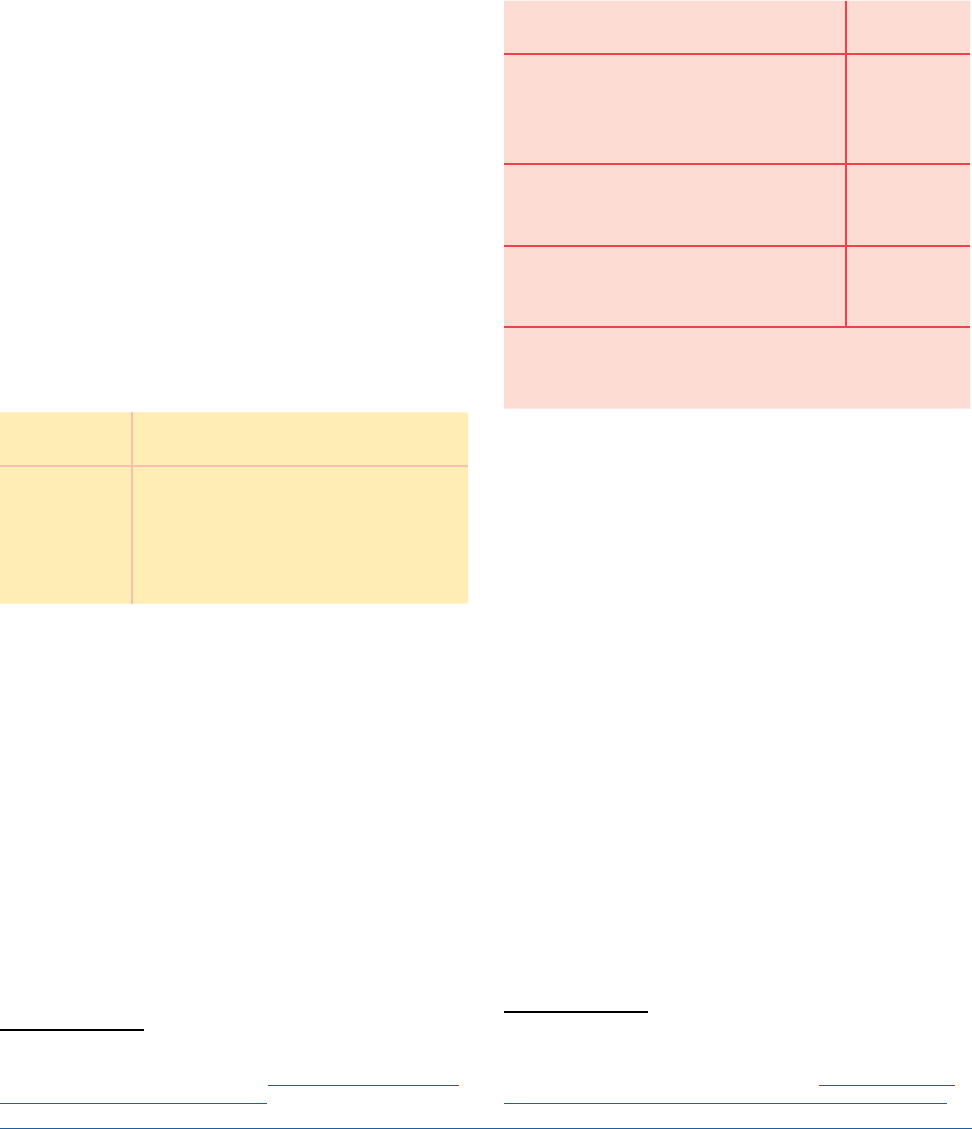

Pathways to decriminalize houselessness

Divest from… Invest in…

•

houselessness

•

response to houselessness

•

•

•

•

2

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Hawai‘i has one of the highest rates of

houselessness in the United States, with Native

Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders composing the

largest group of unhoused residents. Rather

than focus on the root causes of this racialized

crisis, public officials have treated houselessness

as a crime, tasking local police departments

with sweeping, citing, and arresting unhoused

individuals at alarming rates. As a result, far

too many people experiencing houselessness in

Hawai‘i have harmful interactions with the police

instead of or before getting access to housing

and mental health services. The efforts of public

officials to rebrand these sweeps—whether using

Orwellian terms like “compassionate disruption”

or simply offensive terms like “sanitation

outreach”—do nothing to change the illegal,

unconstitutional, and counterproductive nature of

these actions.

ACLU of Hawai‘i

Why it’s worth it

With the resources spent on:

Honolulu could:

ACLU of Hawai‘i

Repeal, defund, and stop enforcing laws

that criminalize houselessness (i.e. stop

sweeps)—Anti-houselessness laws do nothing

to stem the flow of entry into houselessness,

and their enforcement is costly, harmful, and

counterproductive.

Prioritize community-building and cultural

change—Counties should listen to houseless

community leaders to co-create solutions to

housing insecurity. Supporting community-

building, self-governance, and public dialogue

between housed and unhoused communities

can help create a more positive and humane

culture regarding houselessness that allows for

sustainable solutions.

Create mobile crisis response services that

are autonomous from police, accessible

to the public, and accountable to the

community—Non-armed mobile crisis response

teams can respond to and support individuals

experiencing behavioral health crises, such as

houselessness, instead of police.

Expand Housing First and wraparound

services—Housing First and wraparound

services are the two most effective supportive

services currently offered by the counties,

according to experts. The biggest hurdle to them

being effective is the magnitude of need.

Grow the inventory of housing that is

affordable to extremely low-income

residents—The shortage of housing that is

affordable to extremely low-income households is

a driver of houselessness and a major barrier to

houseless individuals reaching stability. Counties

can play a role in growing the inventory through

property acquisition, community land trusts, and

incentivizing development.

Strengthen tenant protections—Tenant

protections like just cause, rent control,

prohibitions on housing discrimination, right

to counsel, and right of first refusal can help

prevent housing loss before it happens and protect

vulnerable renters.

Increase the minimum wage—Raising the

minimum wage to a living wage can reduce

housing insecurity and help prevent housing loss.

By making these investments and enhancements

of residents’ rights, Hawai‘i can reduce harmful

interactions between police and unhoused

residents, better meet the needs of unhoused

and housed communities, reduce racial and

ethnic disparities in houselessness, and end the

criminalization of poverty.

SUMMARY OF

RECOMMENDATIONS:

ACLU of Hawai‘i

CONTENTS

Houselessness in Hawai‘i

ACLU of Hawai‘i

INTRODUCTION

“Respect alike (the rights of) men great and humble; See to it that

our aged, our women, and our children lie down to sleep by the

roadside without fear of harm.”

—King Kamehameha I

at reparations through the Hawaiian Homes

currently enough permanent housing support

ACLU of Hawai‘i

11

11

ACLU of Hawai‘i

PART 1: PROBLEM OVERVIEW

Houselessness in Hawai‘i

Hawai‘i has long been one of the states with the

highest rates of houselessness per capita in the

country, with 45 out of every 10,000 residents

experiencing houselessness in the state.

12

In

2020, there were about 6,500 people experiencing

houselessness, statewide.

13

On O‘ahu, the most

populous island, about 53% of the unhoused

population was unsheltered, meaning that they

lived on the street, or another place not intended

for sleeping accommodation, rather than in

shelter. Across the neighbor islands, about 65%

of the unhoused population was unsheltered.

Certain groups of people are disproportionately

represented among the unsheltered—Native

Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and Black folks,

gender and sexual minorities, individuals with

disabilities, veterans, survivors of domestic

violence, and men, are overrepresented.

14

For

example, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders

compose 10% of the population of O‘ahu, but 31%

of the houseless population.

The unhoused population in Hawai‘i is likely to

grow in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even before the start of the pandemic, one quarter

of households in Hawai‘i were at risk of being

forced out of their homes after two months or less

of sustained income loss.

15

By February 2021, one

year into the pandemic, 62% of Hawai‘i residents

surveyed reported that it was very or somewhat

12

likely that they would leave their home due to

eviction in the next two months.

16

The magnitude of the unhoused population and

the growing vulnerability of Hawai‘i residents to

houselessness is indicative of systemic drivers of

houselessness including an affordable housing

shortage and low wages. More than half of

Hawai‘i renters do not live in affordable housing,

meaning that their housing costs consume 30% or

more of household income.

17

Extremely low-income

residents are in an especially dire situation, often

spending more than half of household income on

rent.

18

Persistently low wages in Hawai‘i are a driving

factor in the mismatch between people’s incomes

and housing costs.

19

The minimum wage in the

state is $10.10 and the average renter in Hawai‘i

earns $17 per hour, even though a living wage

in Hawai‘i is $20.61.

20

Working full-time, the

average renter’s wages come to $2,720 in monthly

earnings. Meanwhile, the average 2-bedroom

costs $2,015—almost three quarters of the

average renters’ monthly wages. In sum, average

renters’ earnings are meager compared to housing

costs. Rising income inequality, a stagnant

minimum wage, and housing development

that has focused on high-end units that are

unaffordable to most local residents

21

have created

an environment in which residents are too often

at risk of losing their housing.

21

ACLU of Hawai‘i

Criminalization of Houselessness

As the unhoused population has become

increasingly visible in Hawai‘i, policing has

become the county governments’ primary

response. Police departments are tasked with

enforcing anti-houselessness policies, responding

to complaints about houseless individuals,

and are actively involved in most county and

state houselessness initiatives. However, police

departments are ill-equipped to connect those in

need with supportive services such as housing

and mental health care services. Furthermore,

police interactions with unhoused individuals

often have a series of deleterious impacts,

increasing the likelihood that individuals are

penalized for their lack of housing through the

criminal justice system, deteriorating trust

between unhoused communities and housing and

mental health service providers, and reducing the

likelihood that unhoused individuals eventually

do secure stable housing. Policymakers’ reliance

on policing to respond to houselessness is

therefore counterproductive and creates a missed

opportunity to use public resources to meet the

needs of unhoused individuals and families.

In this report, the “criminalization of

houselessness” refers to the processes by which

being houseless has been made into a crime

in Hawai‘i. These include the creation and

enforcement of policies at the state and county

level that prohibit conduct performed primarily

by unhoused people, such as sleeping, sitting or

lying down in public spaces, or living in vehicles

in public space.

22

This report will focus on the

impacts of how police officers, whose responsibility

it is to prevent, detect, and investigate crimes,

have become first responders to houselessness

and play leading roles in government initiatives

to provide supportive services to unhoused

individuals and communities, a role for which

police are largely untrained and which would be

more effectively provided by social workers and

other similarly trained professionals.

22

Honolulu is criminalizing

houselessness.

In 2014 former Mayor Kirk Caldwell declared

a “war on homelessness,” initiating a series of

laws that have effectively made being unhoused

a crime in Honolulu. Since then, the City has

passed increasingly comprehensive and punitive

ordinances that allow the city to use police force

against those living on the streets, including

the Sidewalk Nuisance Ordinance, the Stored

Property Ordinance, Urination/Defecation bans,

and a series of Sit-Lie bans that make it illegal to

sit or lie down in Waikīkī and parts of 17 other

neighborhoods.

23

Meanwhile, park closure rules

make it a crime for unhoused individuals to sleep

in city parks at night or have tents in parks at

any time, often leaving individuals without access

to shelter no options but to violate sit-lie bans.

24

These policies have earned Honolulu a place

in the National Law Center on Homelessness

and Poverty’s “hall of shame” - one of four cities

across the country that has aggressively enforced

criminalization laws in a particularly harmful

way.

25

Under Mayor Rick Blangiardi, there has

been a sharp increase in citations related to these

policies.

26

The mechanisms by which the Honolulu Police

Department enforces anti-houselessness policies

range from unplanned interaction with unhoused

individuals during daily patrols, to formal sweeps.

The latter, officially called “enforcement actions”,

are planned events run by the Department of

Facility Maintenance (DFM) in coordination

with the Honolulu Police Department (HPD) in

which city officials seize and impound or destroy

unhoused persons’ property under authority of

ACLU of Hawai‘i Decriminalizing Houselessness in Hawai‘i 11

the Sidewalk Nuisance Ordinance and Stored

Property Ordinance. These sweeps involve DFM

officials roping off areas in which houseless

communities reside and seizing any property

that residents were not able to carry away prior

to the sweep and impounding or discarding those

belongings.

27

It is illegal for the city to throw away

people’s belongings during sweeps, but houseless

individuals report that the practice is still

common.

28

HPD officers detain any individuals

who attempt to cross the roped off areas without

authorization.

One purported goal of sweeps is to encourage

houseless people to enter shelters so that they

can receive services. However, sweeps are

devastating for residents whose belongings are

seized or destroyed, having negative economic,

physical, psychological impacts that can actually

prevent individuals from securing housing. In

fact, in a survey of unhoused individuals who had

experienced sweeps, only 11% stated that they

were more able or likely to seek shelter after a

sweep.

29

Meanwhile, national evidence indicates

that sweeps are ineffective at reducing visible

houselessness—the other main purported purpose

of sweeps.

30

Sweeps are counterproductive and harmful in the

following ways:

• Involvement with the penal system sets people

back. – Police often fine, cite, and arrest

unhoused individuals during sweeps (Figure

1).

31

Getting fined, cited, and/or arrested is

costly and further diminishes unhoused

individuals’ economic security, and

consequently, the likelihood of attaining

housing.

• Losing property and identification diminishes

economic stability. – It is common for various

means of identification to be lost, confiscated,

and/or discarded by City officials during

sweeps.

32

Losing identification can make

it nearly impossible to get a job or attain

housing and once lost, it can be costly and

time-consuming to replace, requiring access to

technology, mailing fees, payment to notaries,

a postal address, and transportation to

government offices.

Figure 1: As Sweeps Continue, City Expenditures and Tickets Rise, January 2020-March 2021

Cumulative Expenditures

Cumulative Tickets

ACLU of Hawai‘i Decriminalizing Houselessness in Hawai‘i 12

• Physical and psychological harm diminishes

well-being. – Sweeps often cause victims

significant physical stress and psychological

harm, compounding the trauma that many

experience while living on the streets.

33

• Unhoused individuals are pushed away

from services. – When unhoused residents

are forced to move away from encampments

and urban areas, they are often forced to

relocate into residential areas, which can

reduce their chance of receiving supportive

services.

34

Sweeps frequently disrupt the

relationships that outreach workers have

built with residents and that residents have

built with each other, undermining the goal of

connecting houseless individuals to services.

35

In addition to formal sweeps, police enforce

Honolulu’s anti-houselessness policies during

beat patrols and in response to complaints about

unhoused individuals from the public. Police

officers enforce anti-houselessness measures

by warning, citing, and arresting unhoused

individuals.

In 2020 following the start of the COVID-19

pandemic, there is evidence that Honolulu Police

Department increased the frequency of citations

to people experiencing houselessness, despite

national guidelines from the CDC to do the

opposite.

36

The Honolulu Star Advertiser reported

that in June of 2020, police officers issued 4,277

citations related to houselessness in Honolulu.

37

In

2021, the practice of enforcing anti-houselessness

policies continues, with 3,833 citations issued

between April and June of 2021.

Since many unhoused individuals find it difficult

or impossible to respond to court summons, it is

common for unhoused individuals to be arrested

and incarcerated for missing court dates, which

can lead to additional fines, fees, and barriers

to accessing housing.

38

Of the 6,591 people who

were admitted into the state of Hawaii’s jails

in 2020, 37.5% of them (2,474) reported being

unsheltered.

39

Further research analyzing

911 calls, warnings, citations, and arrests are

required to estimate the full costs of informal

sweeps to taxpayers.

ACLU of Hawai‘i

Honolulu’s anti-houselessness policies

• Sit-Lie bans:

• Sidewalk Nuisance Ordinance:

• Stored Property Ordinance:

• Urination/Defecation bans:

• Park closures:

• Park tent bans:

Criminalization comes with a cost.

Enforcement of Honolulu’s anti-houselessness

policies costs taxpayers millions of dollars each

year. In FY 2020, the Department of Facility

Maintenance carried out 1,634 sweeps over the

course of 320 days, an average of more than 5

sweeps per day.

40

In 2014, Hawai‘i News Now

reported that sweeps cost the city about $15,000

per day.

41

Using a conservative approach (that

assumes the daily costs of enforcement have not

risen since 2014), sweeps cost the city at least $4.8

million in 2020.

Beyond sweeps, daily enforcement is also costly

in terms of police time. In 2017 Honolulu Police

Captain Mike Lambert reported that police in his

district were overwhelmed with houselessness-

related complaints, receiving 30-40 calls each

day, each of which take at least 30 minutes to

respond to.

42

In addition to police staff time, the

criminalization of the unhoused creates a slew of

additional costs to taxpayers related to processing

citations, making arrests, court-appearance

related costs such as judges, court officers, and

public defenders, and incarcerating individuals.

While this report focuses on county-level

responses to houselessness, the state also

regularly conducts sweeps of houseless individuals

living on state land. In 2020, for example,

$7 million in state funds were budgeted for

conducting sweeps.

43

ACLU of Hawai‘i

Criminalization fails to address the causes

of houselessness, and instead worsens the

problem.

Enforcement of Honolulu’s anti-houselessness

policies results in displacing and usually

temporarily relocating people to different public

spaces. Such laws do not solve houselessness,

or even reduce visible houselessness within a

given area in the long-term.

44

In fact, there is

evidence that sweeps can lead to more houseless

encampments and complaints from the public.

45

This is because criminalization does not address

the leading causes of houselessness, such as

high costs of living, income inequality, or lack

of affordable housing (Table 1). To the contrary,

citations, arrests, and convictions create added

barriers to unhoused individuals obtaining

housing, employment, and financial security.

46

In addition, sweeps disconnect people who are

unsheltered from service providers who know

where they are and have built up relationships

with them. Therefore, policies that criminalize

houselessness in Hawai‘i actually undermine

the government’s investments in housing and

supportive services.

Criminalization harms public health.

The criminalization of houselessness harms public

health. Displacing people who have nowhere

to keep their belongings, clean themselves, or

discard waste, puts these individuals as well as

the entire community at risk.

47

In recognition

of this fact, the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention released guidance for service providers

and local officials during the COVID-19 pandemic,

urging officials to halt sweeps and ensure nearby

restroom facilities remain open 24 hours per day

to people experiencing homelessness.

48

In direct

opposition to these guidelines, which are intended

to reduce spread of the

disease, Honolulu closed

park restrooms on March 23, 2020 and they

remained closed until, under significant public

pressure, the City agreed to open the bathrooms

Table 1

STRUCTURAL

drivers of houselessness:

INDIVIDUAL

drivers of houselessness:

Disability status

ACLU of Hawai‘i

on the condition of a group of houseless leaders

cleaning the bathrooms themselves.

49

Honolulu

also continued regular sweeps throughout the

pandemic (Figure 1). In fact, several members

of the group of houseless volunteers who were

regularly cleaning public restroom facilities

were cited and sent to jail for outstanding park/

sidewalk citations.

50

These sweeps continue in

Honolulu today, although they are sometimes

referred to by city officials as “sanitation efforts.”

51

Criminalization deepens racial and ethnic

disparities.

The negative effects of the criminalization of

houselessness fall most heavily on the shoulders

of those that tend to be disproportionately

represented among the unhoused and overpoliced.

Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders, including

those who have origins in any of the original

peoples of Hawai‘i, Guam, Samoa, Micronesia,

or other Pacific Islands, make up the largest

percentage of unhoused individuals in Honolulu

and are significantly disproportionately

represented among the unhoused in comparison

to their share of the general population.

52

Blacks

are also disproportionately represented among

the unhoused. At the same time, there is evidence

that Black, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander

communities experience force at the hands of

the police at higher rates than other Hawai‘i

residents.

53

Racial and ethnic disparities in houselessness and

policing mean that Native Hawaiians and Blacks

are more likely to be criminalized by Honolulu’s

anti-houselessness policies than other racial

and ethnic groups. Recent evidence supports

this point. During the first three months of the

COVID-19 pandemic, Honolulu police officers

arrested Micronesians, Blacks, and Samoans

for violating the COVID-19 stay-at-home orders

at far higher rates than their representation in

the general population.

54

Houseless individuals

were also disproportionately represented among

those arrested, and additionally were often

charged with infractions related to the City’s anti-

houselessness policies.

As discussed above, criminalization reduces

unhoused individuals’ access to housing,

employment, and financial security, thereby

deepening systemic inequities experienced by

Native Hawaiians and Blacks and creating a

reinforcing problem cycle (Figure 2).

Honolulu’s anti-houselessness policies may

be illegal

Since Honolulu’s anti-houselessness policies target

houseless individuals, they may violate the equal

protection clause of the 14th amendment. Also, in

2019, a U.S. Supreme Court decision affirmed that

it is unconstitutional to punish houseless people

for sleeping in public if there aren’t enough shelter

beds to accommodate them because it violates the

Eighth Amendment.

55

Honolulu’s shelter beds fall

far short of being able to accommodate the city’s

Figure 2: Criminalization deepens racial

inequities and housing insecurity

ACLU of Hawai‘i

unhoused population.

56

However, city officials

have argued that the court opinion does not

prevent the city from enforcing its criminalization

policies because enforcement occurs in one

neighborhood at a time, rather than across the

entirety of Honolulu at once.

57

The Houselessness Services

Landscape

There are a number of state and local initiatives

that aim to connect unhoused individuals with

supportive services that are intended to help

them secure and maintain stable housing. The

state houselessness service system in Hawai‘i

is coordinated by two Continua of Care (CoC)

agencies: Partners in Care on O‘ahu and

Bridging the Gap on the neighbor islands.

CoCs are regional or local planning bodies that

coordinate housing and services funding for

houseless families and individuals. They are

responsible for tracking houselessness, operating

the Homeless Management Information System

(HMIS) to collect data on the provision of housing

and services to the houseless, coordinating the

implementation of local service systems, and

applying for funds from the U.S. Department of

Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

58

The CoCs oversee the Coordinated Entry

System, which is mandated by HUD and

prioritizes assistance to unhoused individuals

and families based on vulnerability and severity

of service needs.

59

Across the Coordinated Entry

System in Hawai‘i, service providers use the

Vulnerability Index and Service Prioritization

Decision Assistance Tool (VI-SPDAT) to assess

individuals’ needs. Each individual who enters

the houselessness services system is assessed

and assigned a VI-SPDAT score, which indicates

their vulnerability according to indicators such as

history of houselessness, substance use, and more.

Individuals with higher scores are prioritized for

more comprehensive services and are placed into

services as they become available.

60

Types of Services

Houselessness services generally fall into 6

categories: permanent housing, transitional

housing, shelter, supportive services, outreach,

and prevention.

61

• Permanent housing (PH) is defined

as community-based housing without a

designated length of stay in which formerly

houseless individuals and families live as

independently as possible. Under PH, a

program participant must be the tenant on

a lease (or sublease) for an initial term of

at least one year that is renewable and is

terminable only for cause. Further, leases (or

subleases) must be renewable for a minimum

term of one month.

• Permanent supportive housing is

permanent housing with indefinite

leasing or rental assistance paired with

supportive services to assist houseless

persons with a disability or families with

an adult or child member with a disability

achieve housing stability. In 2020, there

were 2,554 permanent supportive housing

beds across the state.

62

• Rapid re-housing (RRH) emphasizes

housing search and relocation services

and short- and medium-term rental

assistance to move unhoused persons

and families (with or without a disability)

as rapidly as possible into permanent

housing. In 2020, there were 1,190 units

ACLU of Hawai‘i

of rapid rehousing resources across the

state.

63

• Transitional housing is designed to provide

unhoused individuals and families with the

interim stability and support to successfully

move to and maintain permanent housing.

Transitional housing may be used to cover

the costs of up to 24 months of housing with

accompanying supportive services. Program

participants must have a lease (or sublease) or

occupancy agreement in place when residing

in transitional housing. In 2020, there were

1,287 units of transitional shelter across the

state.

64

• Shelter

• Emergency shelters are facilities

with the primary purpose of providing

a temporary shelter for the unhoused

in general or for specific populations of

the unhoused and which do not require

occupants to sign leases or occupancy

agreements. In 2020, there were 2,101

Emergency Shelter & Safe Haven beds

across the state.

65

• Supportive Services provide services

to houseless individuals and families not

residing in housing operated by the service

provider.

• Outreach is conducted with sheltered and

unsheltered houseless persons and families

in order to link clients with housing or other

necessary services and provide ongoing

support.

• Homelessness Prevention assistance for

those at risk of houselessness includes housing

relocation and stabilization services as well

as short- and medium-term rental assistance

to prevent an individual or family from

becoming unhoused. Houselessness prevention

can help individuals and families at-risk

of houselessness to maintain their existing

housing or transition to new permanent

housing.

Adequacy of Services

According to one report on houselessness services

utilization on O‘ahu, the population of individuals

and families that utilized homelessness services

in 2020 roughly reflected the racial breakdown

of individuals experiencing houselessness.

66

However, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders

were under-represented in permanent supportive

housing programs. One quarter of all individuals

in contact with the system were in the process

of assessment, awaiting placement into services.

Among those who were receiving services, the

most common direct service was homelessness

prevention (in which families with children were

overrepresented), followed by outreach. The report

authors recommended extensive investment in

permanent supportive housing programs for

single adults with disabling conditions as well

as rapid rehousing and homelessness prevention

assistance for single adults who may be at-risk for

houselessness or are newly houseless.

According to a state report to the legislature in

2021, the number of beds to address houselessness

across Hawai‘i has increased over time.

67

Between 2015 and 2019, permanent beds—

which include rapid rehousing and permanent

supportive housing—increased by 167%. Despite

the increase in permanent housing inventory,

however, the number of unsheltered individuals

on O‘ahu also increased, exacerbating unmet

demand. Additionally, many shelters have rules

and requirements that restrict who can stay in

shelter beds (some only accept families, others

do not allow pets, many have time restrictions

on length of stay, etc.) Therefore, available beds

do not necessarily represent options available to

unsheltered individuals.

ACLU of Hawai‘i

Houselessness

Initiatives

Other Expenses

Funding for Services

In fiscal year 2021, the Hawai‘i Interagency

Council on Homelessness reported that core

houseless programs across the state received:

• $20 million in federal funds from the

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development (HUD), the majority of which

were spent on permanent supportive housing

(Figure 3).

• $33 million in state funds, which were spent

primarily on emergency shelter, prevention,

and outreach.

• $9 million in county funds, which were

primarily spent on permanent supportive

housing and emergency shelter.

68

The state receives federal dollars that are

funneled through the CoCs and also appropriates

funds from the general fund. The counties

manage federal dollars from the Community

Development Block Grants and spend relatively

small portions of their own general funds on

addressing or serving houseless people.

County Spending on Houselessness

• Honolulu spends approximately $10 million

in county funds on houselessness initiatives

annually, representing less than 1% of the

county’s $3 billion operating budget (Figure

4).

69

This $10 million in county funds for

houselessness is also about 30 times less than

what Honolulu spends on policing.

70

Honolulu Civil Beat

• Maui County spends about $240,000 on its

Homelessness Program and grants $3.3

million to non-profit agencies that address

houselessness within the county.

71

• Kaua‘i County allocated approximately $2.2

million in county funds to the Kealaula

Housing Project for houseless families and

spends $93,936 per year on the Homeless

Coordinator position for the County of Kaua‘i

Housing Agency.

72

• Hawai‘i County staff manage lease

agreements and work with state agencies

and non-profits to address houselessness. The

county also budgets non-profit grant funding

that can be used to address houselessness.

However, there is no dedicated dollar amount

allocated to address houselessness.

73

Figure 3: Hawai‘i Houseless Program

Funding, FY 2021

Figure 4: Spending on houselessness

services is less than 1% of Honolulu’s

operating budget, FY 2021

++

+1

53%

State

32%

Federal

15%

County

ACLU of Hawai‘i

Police Involvement in Houselessness

Initiatives

Beyond responding to 911 calls regarding

unhoused individuals, local police departments

are formally involved in a significant portion

of state and local houselessness initiatives in

Hawai‘i. In addition to working with a variety of

service providers, shelters, and local initiatives,

74

the Honolulu Police Department has three

programs focused on houselessness:

Homeless Outreach and Navigation for

Unsheltered Persons (HONU)/Provisional

Outdoor Screening and Triage Facility

(POST)

The City and County of Honolulu Department

of Community Services and Honolulu Police

Department received $6 million in state ‘Ohana

Zone funds to create HONU, two mobile short-

term shelter and navigation sites.

75

In response

to the COVID-19 pandemic, the project shifted to

become POST, a quarantine facility that provided

COVID-19 screening, triage, and isolation

facilities to mitigate the spread of COVID-19

among the unhoused population in Honolulu.

While the City has characterized POST as

“shelter,”

76

HUD has repeatedly rejected that

characterization. One HUD director explained

that “POST is just a City endorsed homeless

tent city” and therefore was to be treated as a

street outreach program. Separately, a system

administrator for HUD described POST in the

following way: “when it’s outside and it looks like

a tent and feels like a tent, and it smells like a

tent, it is a street outreach program; it’s not a

shelter.”

77

Health Efciency Long-term Partnership

(HELP)

Between 2017 and the start of the COVID-19

pandemic, HELP was a project that organized

monthly joint agency outreach days involving

police officers and service providers. In teams

of two, service providers offered houseless

individuals supportive services and police officers

offered rides to nearby shelters for those who

chose that option, when spaces were available.

The program also created a shared database

between the Honolulu police department and

service providers to track houseless individuals.

78

Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD)

LEAD is a pre-booking diversion program that

aims to divert individuals who have committed

minor offenses away from the criminal justice

system and into the social service sector.

79

Variations of LEAD exist in Honolulu, Kaua‘i,

Maui, and the Island of Hawai‘i. In Honolulu,

LEAD diversion referrals had not begun as of

early 2020 and as of mid-2021 the program is still

not being heavily utilized. However, police officers

who interact with houseless individuals can refer

them to LEAD wraparound supportive services.

ACLU of Hawai‘i

PART 2: INTERVIEW FINDINGS

The following findings are based on interviews

with 6 service providers, 5 government employees,

3 community organizers, 3 academics, 2

individuals who have experienced houselessness

in Honolulu, and 1 employee of a philanthropic

organization. Interviewees explored the following

broad topic areas:

1. What should the role of the police be

in responding to houselessness? What

are the consequences of the current role of

the police in responding to houselessness?

What changes can the Hawai‘i counties make

to better serve the needs of the unhoused

population?

2. What services are needed? How can

existing houselessness services be improved

or replaced to better serve the needs of the

unhoused population? What existing or

new housing or supportive services merit

investment at the county level?

Policing

The following themes emerged regarding the role

of the Honolulu Police Department in responding

to houselessness:

Shortcomings of current system

•

•

•

•

Areas for investment

•

Shortcomings of current system

Like most parts of the country, when 911

receives a call regarding an individual that

is unhoused and/or having a behavioral

health crisis in Hawaii, it is the local police

department that responds.

80

This response

occurs by default because of an absence of viable

public health alternatives, rather than because

police departments are best suited to support

individuals that are unhoused and/or during a

behavioral health crisis.

Most interviewees agreed that police departments’

role as first responders to houselessness is unideal

at best, and harmful at worst. Interviewees

explained that police are currently heavily

involved in responding to houselessness in

Hawai‘i but had concerns about law enforcement

being the primary structural response to

houselessness. One service provider said, “I think

that as a system, the way that they [the police]

are working with the houseless is not beneficial

to anybody.” They explained that interactions

between unhoused individuals and police often

result in officers issuing citations and arrests,

which can decrease unhoused individuals’ chances

of accessing housing and supportive services.

Another service provider expressed that the police

are currently filling a function that nobody else

is doing, but that would be better done by social

workers or mental health workers: “The police

are really the only government response. They’re

the only ones in the field, giving people rides to

shelter, for example. But that shouldn’t be their

role.” Police officers are not professionally trained

to support individuals undergoing behavioral

crises, including houselessness.

ACLU of Hawai‘i Decriminalizing Houselessness in Hawai‘i 21

The police in Honolulu are also responsible

for the enforcement of laws that criminalize

houselessness, primarily through sweeps. Several

interviewees discussed the harmful effects of

police sweeps on unhoused communities. One

person experiencing houselessness who currently

lives in a shelter in Honolulu described living

through sweeps:

The sweeps are so bad. They just displace us.

It doesn’t make any sense. They come in the

middle of the night. I’ve woken up to a sweep

happening. We’ve had to stay up all night,

waiting for them. And do you know how

many important documents I’ve lost during

the sweeps? Medical papers, ID, records,

everything. They throw them away and they

tell us we can go get our stuff in a warehouse

somewhere, but how do we get there? I’ve

heard that it’s not even true, even if you can

get there.

I just don’t understand how they think it will

help anything. To just displace us and make

us even worse off. Usually people just move

from one side of the street to the other to wait

it out. And in the meantime, the vultures

come—people come when they know sweeps

are happening to steal things.

Some interviewees offered ideas of how to build

the political will to stop sweeps. Since sweeps

often occur in response to complaints from

the public about houseless encampments, one

community advocate explained how increasing

dialogue between housed and unhoused

communities can increase mutual trust and

understanding and reduce instances of housed

residents calling on the police to sweep unhoused

residents. For example, in Waimīnalo and

Wai‘anae, leaders from houseless encampments

have attended neighborhood board meetings to

communicate with local housed residents about

community issues. Other interviewees suggested

that the laws criminalizing houselessness need to

change in order stop sweeps.

Interviewees were generally ambivalent about the

Honolulu Police Department’s HELP program,

which has been paused since the start of the

pandemic. HELP involved the police conducting

occasional joint outreach efforts with service

providers to unhoused communities. One

interviewee explained that the HELP program

allowed rookie police officers the opportunity to

learn how to interact with houseless individuals

productively. However, the same person pointed

out that the HELP program eroded trust between

service providers and houseless individuals

because service providers became associated

with police and HELP outreach days commonly

preceded sweeps.

Interviewees had mixed feelings about POST,

HPD’s quarantine facility composed of a

compound with tents and restroom facilities.

One objective of HONU/POST is to divert

houseless individuals from citation and arrest.

However, some interviewees expressed concern

that houseless individuals were coerced into

joining POST. When houseless individuals were

threatened with citation or arrest during the

pandemic, they were given the option of avoiding

arrest by going to POST instead, where they did

not have in and out privileges. Some felt this

was akin to incarceration. One houseless person

explained: “It was like prison. I agreed to go

because I was so tired of the sweeps. But they had

us locked up and we couldn’t leave.”

A few interviewees discussed the merits and

shortcomings of the Honolulu Police Department’s

LEAD program. In terms of the program’s

strengths, interviewees noted that the program’s

wraparound services benefit participants and

that the intention behind the program to reduce

the involvement of unhoused individuals in the

criminal justice system is valuable. However,

three interviewees pointed out that the

program has fallen short of its goals of diverting

individuals from arrest. Two interviewees

explained that the diversion component of the

program is not happening because of a lack of

buy-in on behalf of police and prosecutors. A 2020

program evaluation of LEAD confirmed that

diversion has not begun and recommended that

the diversion arm of the program begin so as to

be able to measure the impact of the program on

arrests and incarceration.

81

ACLU of Hawai‘i Decriminalizing Houselessness in Hawai‘i 22

Areas for investment

Alternative Mobile Crisis Response Models:

Over half of interviewees expressed interest in

the possibility of creating non-armed mobile crisis

response services to respond to houselessness

and related behavioral and mental health

crises instead of police. This interest among

interviewees echoed national conversations on

reimagining safety that have highlighted mobile

crisis response services as a key strategy for

reducing police involvement in houselessness.

82

Mobile crisis response services can be structured

in a variety of ways, but generally involve teams of

non-armed behavioral or mental health specialists

who can provide a mobile response to crises,

instead of police. At the national level, the models

of mobile crises response services receiving

the most attention as offering alternatives to

reliance on policing are those that divert 911 calls

regarding non-violent crises to civilian teams who

can respond without police or Emergency Medical

Services (EMS).

83

Once on site, these mobile crisis

response teams can provide care and assistance

required and can call for police or EMS back-

up if necessary. There are also models of mobile

crisis response called Mental Health First models

that are completely autonomous from police,

involve non-police dispatch and implementation,

and are typically created by and accountable to

communities that are most impacted by mental

health crises and police violence.

84

According to a 2021 report reviewing mobile

crisis response programs, for mobile crisis

response programs to effectively reduce or

eliminate harmful interactions with police,

non-police responders must have autonomy from

police departments, have sufficient resources to

be able to be dispatched in response to 911 (or

another publicized and widely accessible system

of dispatch) 24/7 across all regions, and must be

accountable to the communities most impacted

by mental health crises and police violence,

among other requirements.

85

A simple method of

remembering these criteria is to think of “triple

A”—autonomy, accessibility, and accountability.

Current Initiatives in Hawai‘i Fall Short

As of September 2021, Honolulu’s new mobile

crisis response program (Crisis Outreach

Response and Engagement or “CORE”)

appears unlikely to substantially reduce police

involvement in responding to houselessness—

first and foremost because it does not meet the

criterion of autonomy from the police. Under the

program, 911 dispatchers will continue to send

police to nonviolent, houselessness-related calls.

Police will then have the option to call the CORE

team (composed of emergency services workers

and social workers) if they choose.

86

Under this

program, police will continue to serve as de-facto

first responders to houselessness. More recent

reporting in October

87

suggests police may be less

involved than previously reported. With the start-

and-stop nature of the CORE roll-out, as well as

the back-and-forth information being provided

about police involvement in CORE, skepticism as

to the level of police involvement, and therefore

the viability of the program, is still warranted.

One of the interviewees for this report explained

that a similar model of police and non-police

co-response

88

to domestic violence incidents had

largely failed in Honolulu in the recent past. The

program, called Safe on Scene, was intended

to reduce the harmful interactions that police

ACLU of Hawai‘i

officers would often have with victims or survivors

of domestic violence, by allowing police officers to

bring a domestic violence advocate to co-respond

to incidents. However, the interviewee, who was

involved with running the program, explained

that the police were largely uncooperative and

usually declined to involve the non-police domestic

violence advocates.

On the state level, a non-armed mobile crisis

response program exists, but has limitations in

serving as a viable alternative to policing. The

Hawai‘i Coordinated Access Resource Entry

System (CARES) coordinates services across

the state to support individuals experiencing

substance use and mental health challenges. An

individual can call the CARES hotline on behalf

of themselves or someone else in need of support

and CARES representatives can dispatch a crisis

mobile outreach (CMO) unit to respond to callers.

However, there are several limitations that

prevent CARES from being a viable alternative

to policing: the CARES line is far less well

known among the public compared with 911,

89

911 dispatch does not coordinate with CARES

to divert calls regarding mental health crises

away from police, and in some circumstances,

police are dispatched to respond to CARES

calls. In other words, the program is limited in

terms of accessibility to the public and autonomy

from police. Despite the existence of the CARES

line, police continue to be first responders to

houselessness across most of the state.

Services

The following themes emerged from interviewees

regarding the services landscape:

Shortcomings of current services

•

• There are not enough customizable

•

Opportunity areas

•

•

•

•

Housing services are urgently needed

Most interviewees said that the short supply

of housing—especially permanent supportive

housing and housing affordable to extremely low-

income households—is a major barrier to serving

the needs of the unhoused population. Many

more houseless people want housing support than

is currently available from the houselessness

services system. Quantitative evidence supports

this claim—the top service need reported by

unhoused individuals is permanent housing.

90

ACLU of Hawai‘i

Permanent Supportive Housing Vouchers

(Housing First)

Several interviewees agreed that providing

more permanent supportive housing vouchers

should be the government’s top priority regarding

houselessness. This finding is supported by a wide

body of evidence that suggests that Housing First

interventions (which provide housing in addition

to mental health, substance use, and other

support services) are an effective way of helping

unhoused individuals achieve greater stability.

91

One service provider explained the benefits of

Housing First: “Vouchers are cheaper and more

effective than shelters, which end up creating

a revolving door of houselessness.” Another

service provider offered the following anecdote

to illustrate the need for further investment in

Hawai‘i:

The real scarcity is the availability of

vouchers. When I was doing outreach, we

did outreach to 300 clients. And out of those

300 people, only 30 got permanent supportive

housing, but that still seemed like a huge

success. A 10% rate was pretty successful.

Some interviewees also suggested that in addition

to providing more Housing First vouchers, county

officials should consider extending the length of

vouchers beyond one year, especially in the wake

of the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic.

One interviewee who is currently housed in

Honolulu through a voucher explained:

After years of being on the street and in

shelter they finally told me I got permanent

supportive housing through a voucher. Then

when I moved in, they told me it was only for

a year. I thought it was permanent. I don’t

know what I’m going to do once the year is

over. My situation won’t have changed by then.

These comments were supported by evidence that

long-term rental assistance can be an effective

long-term solution to houselessness, as it is more

effective at increasing housing stability and more

Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne

de Psychiatrie

cost-efficient than short-term forms of support

such as transitional housing and emergency

shelters.

92

Acquire Property

Another solution to the shortage of housing that

is affordable to low-income and extremely low-

income households is for the government to secure

more units of permanently affordable housing.

Multiple interviewees suggested that the counties

can directly purchase and acquire housing

units and offer them to low-income families and

extremely low-income families at affordable rates.

By acquiring housing directly, the counties can

ensure that affordability is maintained. One

houselessness services funder said, “I think the

county definitely needs to be more aggressive

about purchasing units, especially for longer-term

supportive housing.”

Incentivize Development of Extremely Low-

income Housing

Finally, interviewees suggested that the counties

can do more to incentivize developers to build

housing that is truly affordable to low-income

and extremely low-income families. Several

interviewees expressed concern that current

incentives for affordable housing fall short by

failing to create pathways for projects to be

approved quickly and by failing to require that

affordable housing projects offer housing that is

actually affordable to low-income and extremely

low-income families, long-term. One service

provider explained:

One of the biggest issues that we have as

a state is that the permitting process is so

laborious that you almost can’t get anything

built here. We need 50,000 units to help us

over the next couple of years, but if we’re not

building them now, we’re looking at losing

more units versus gaining them. The city

has the capability to change some of those

policies and procedures that could really

allow for affordable housing to be developed.

ACLU of Hawai‘i

A representative of a community-based

organization emphasized the need to think

carefully about affordability thresholds and

requirements: “We need housing that is truly

affordable and what that means is people can

sustain it on very low incomes.”

Wraparound services

Wraparound services were a frequently cited gap

and a promising area for investment, echoing best

practices literature on addressing houselessness.

93

A wraparound services approach takes a holistic

view in understanding an individual’s full set of

needs. In the context of unhoused individuals, a

wraparound services approach considers needs

beyond housing that may influence an individual’s

well-being. Recipients of these services also

typically get choices regarding which services

they might utilize. Commonly needed wraparound

services include cash assistance, transportation,

child care, job placement and support, food

assistance, and legal services. A wraparound

services approach also involves providing services

that are particularly relevant to certain groups

such as domestic violence survivors, non-English

speakers, gender and sexual minorities, and

youth, among others.

Several interviewees pointed out that wraparound

services can help individuals who are receiving

housing assistance to succeed in maintaining

housing and, when applicable, transition into

independent housing. One service provider

explained: “There needs to be improved

wraparound services to help people stay housed

after their vouchers run out and that are specific

to the needs of individuals or families, like help

getting documentation, or help getting a job.”

Government Requirements of Service

Providers

Two major concerns regarding government

requirements for service providers were voiced

multiple times during interviews, about metrics of

success and the prioritization of service provision.

First, several interviewees expressed concerns

that the metrics that public agencies use to

measure success across the houselessness system

create perverse incentives for service providers.

Specifically, that metrics incentivize service

providers to move unhoused individuals through

the houselessness services system as quickly as

possible, without taking individuals’ specific needs

into account, thereby missing the opportunity to

provide individuals with the supportive services

they may need to maintain housing, health, and

well-being, long-term.

One community advocate explained:

The city and state contracts use outcome

measures that are narrowly defined around

moving people through the system quickly...

That deadline and that narrow definition

of success makes it really hard to customize

supports for people, which is the only way to

actually help people get into a better place in

their lives in a sustainable way.

The second major challenge facing service

providers is that complying with government

requirements regarding prioritization of service

provision can create missed opportunities for

connecting more people with housing. Service

providers are required to prioritize service

delivery to individuals who receive higher

vulnerability scores according to the VI-SPDAT

94

tool. For example, an unhoused individual with

comorbidities and who is chronically houseless

is much more likely to receive services than an

unhoused individual who has been houseless

for only a year and is in decent health.

95

While

interviewees acknowledged the value in providing

services to those in greatest need, they pointed

out that an unintended consequence of this

system is that many unhoused individuals that

need only a limited degree of services in order

ACLU of Hawai‘i

to stabilize their situation have little hope of

receiving any. As one service provider explained:

We house a lot of the people at the top of

the list, but there are hundreds that we

cannot help because their vulnerability

score is too low and they will never get to

the point where they are next on the list for

permanent supportive housing or long-term

rapid housing. It’s an extremely frustrating

situation because these people that are not as

vulnerable will probably be more successful

in housing than the people that have so

many issues going on.

Other interviewees agreed that the current rules

around prioritization create gaps in access to

services. One community advocate expressed

frustration that because of the scoring system,

an individual has to be houseless for a year in

order to qualify for any services. Over the course

of one year living on the street, that individual

is likely to experience trauma and threats to

their health and safety which can decrease their

long-term prospects of financial security and

well-being. Another interviewee explained that

there are too many people “in the middle,” who

are not vulnerable enough to get vouchers, but not

independent enough to qualify for rapid rehousing

assistance, who get left behind under the current

system.

Culture

In addition to highlighting areas from which

to divest and areas to invest to support the

unhoused population, culture emerged as an area

of opportunity for change in the interviews.

Shortcomings of current culture

•

Areas for change

•

•

•

Several interviewees expressed concern that the

widespread dehumanization of unhoused people

and communities has driven the criminalization

of houselessness. The unhoused population is

often blamed for a wide array of neighborhood

problems related to sanitation, safety, commerce,

tourism, and more. One community advocate

explained that it is common in neighborhood

board meetings across Honolulu for the majority

of agenda items to be related to houselessness.

Another service provider lamented how affordable

housing projects often face vitriolic opposition by

residents who fear that housing low-income or

formerly unhoused residents will decrease the

safety and/or value of their neighborhoods. When

affordable housing is built despite opposition, it is

not uncommon for the vocal opponents to regret

their initial opposition to it.

96

The widespread scapegoating of the houseless

population for countless social ills often involves

or results in calls to police officers, who represent

the only form of government assistance most

communities can rely on to physically show up

and intervene in any given situation. Police

intervention can lead to harmful interactions

between police officers and unhoused individuals,

as well as citations and arrests of unhoused

individuals that do not remedy the drivers of

houselessness or provide unhoused individuals

with services or support they may need.

ACLU of Hawai‘i

the village have organized a variety of systems

ranging from safety patrols to community

governance to regular community-building events,

which residents say make them feel safe and at

home. The village operates on the principle that

“community provides an answer,” and requires

residents to actively participate in the community

through service.

98

The level of community

organization in the village has enabled residents

to enjoy improved mental and physical health and

get connected to permanent supportive housing

services.

99

In fact, in 2020 Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae

purchased a 20-acre parcel of land to build a

permanent village of affordable housing for 250

residents. The permanent village will continue to

be self-organized and provide “safety, healing, and

purpose through a community of aloha.”

100

Community building has also been a focus at

the Hale Mauli Ola shelter where Hui Aloha, a

volunteer-driven organization, has been operating

a community-building project involving regular

community service days and community meetings

for over a year. Program participants say that

involvement in the project has provided healing,

mental health support, and skill building.

Involvement with the community has also helped

participants navigate the supportive services

system and access housing. The Hui Aloha

volunteer network’s efforts to build community

have also helped improve relations between

houseless encampments and adjacent housed

communities, which have reduced the frequency of

sweeps by police.

101

Overall, investing in community-building at

places such as shelters and encampments can

improve quality of life for unhoused residents,

improve health and safety for all, and reduce

the criminalization of houselessness. Partnering

with unhoused community leaders as well

as organizations like Hui Aloha, can provide

government officials and service providers with

context-specific pathways to support community-

Create avenues for dialogue between housed

and unhoused communities

Opportunities for housed and unhoused

individuals and communities to communicate

with each other can reduce fear and

misunderstanding, prevent the criminalization

of houselessness, and improve quality of life for

all. Government officials, advocates, and service

providers can consult with unhoused community

leaders to design avenues for dialogue that allow

unhoused community members to feel safe,

respected, and able to engage.

There is anecdotal evidence that bringing

unhoused and housed communities together to

discuss local issues has a range of benefits. On

O‘ahu, for example, unhoused residents from the

oldest and largest houseless encampment called

Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae have organized regular

meetings with local businesses and residents

to discuss local issues and address concerns

that housed residents may have regarding

the encampment. Residents of Pu‘uhonua o

Wai‘anae , or “the village,” also regularly attend

neighborhood board meetings.

97

As a result of

frequent communication, residents have been

able to respond to community concerns regarding

health and safety and foster collaborative

relationships with local leaders. Additionally,

the Pu‘uhonua O Wai‘anae community’s efforts

have created the political will to prevent sweeps

of their community, which would have displaced

hundreds of unhoused residents. The fact that the

majority of residents are Native Hawaiians makes

their efforts especially meaningful in combating

criminalization, which tends to disproportionately

harm Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders.

Support community-building and organizing

within unhoused communities

Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae also shows that when

unhoused communities develop trusting,

supportive, and accountable community, there

are a range of benefits that can help reduce the

likelihood of harmful interactions between police

officers and unhoused residents. Residents of

ACLU of Hawai‘i

building and generate the myriad of benefits it

provides.

Shift rhetoric to center common humanity

and dignity

Several interviewees from community

organizations, service providers, and academia

agreed that state and local government’s focus

on sweeps and “enforcement” as a response

to houselessness in Hawai‘i has contributed

to a common perception among the general

public that unhoused people are criminals and

less than human. Beyond halting sweeps and

removing policies that criminalize houselessness,

interviewees suggested that a crucial step

to improving relations between housed and

unhoused communities and reducing harmful

interactions between police officers and the

unhoused is for government officials and elected

leaders to shift rhetoric regarding houselessness

to highlight the common humanity and dignity

of all people, regardless of housing status.

Shifting the narrative on houselessness can also

help reduce the NIMBY-ism that has prevented

affordable housing developments from being

successful.

102

The following guidelines can be

helpful:

• Avoid using language that creates an “us”

versus “them” dynamic between housed and

unhoused communities.

103

• Stop stereotyping houseless people (avoid

implying that all unhoused people share

certain characteristics).

• Use the terms “unhoused” or “houseless”

rather than “homeless” to respect the wishes

of many unhoused people and center the

dignity of individuals who are experiencing

houselessness.

• Emphasize that unhoused people are

legitimate residents and members of the

community—a fact that is recognized under

federal law.

104

• Acknowledge the structural drivers of

houselessness such as income inequality and

lack of affordable housing.

• Avoid placing blame on unhoused residents for

being unhoused.

Shifting rhetoric in these ways can contribute to

a cultural shift regarding how houselessness is

perceived that can improve community health,

safety, and well-being, and reduce the frequency of

interactions between police officers and unhoused

residents that result from fear and distrust,

rather than true public safety risk.

ACLU of Hawai‘i

A union of and for the houseless

ACLU of Hawai‘i

PART 3: BUDGET ANALYSIS

Public budgets are moral documents that should

reflect the values and priorities of the people. The

following section provides analyses of how the

four counties in Hawai‘i are currently spending

public dollars, and highlights opportunities for

reallocated investment. Calculations are based

on publicly available county operating budgets as

well as records requested from local agencies and

email correspondence with county officials.

Almost one-third of county

resources are spent on policing.

Hawaii’s counties spend between 24% (Maui) and

37% (Honolulu) of General Fund expenditures on

police departments (Figure 5).

105

When the four

counties’ resources are combined, they spend 32%

of county resources on police. In other words,

about one-third of local taxpayer dollars are spent

on policing in Hawai‘i (Figure 6).

Police expenditures are staggering compared with

spending on houselessness:

• Honolulu spends 31 times as much on policing

as on addressing houselessness.

• Kaua‘i spends 16 times as much on policing as

on addressing houselessness.

• Maui spends 20 times as much on policing as

on addressing houselessness.

• Hawai‘i County spends 30 times as much on

policing as on non-profit grants in aid, some of

which can be used to address houselessness.

++

HonoluluHawaii County

29 37

71 63

++

27 24

73 76

Kaua‘i Maui

Figure 5: General Fund Expenditures

by Department and County

Police Department

Houselessness

Police

Everything Else

Hawai‘i

Figure 6: Expenditures on Policing

versus Houselessness, by County

Honolulu Hawai‘i Maui Kaua‘i

ACLU of Hawai‘i

To contextualize this distribution of public

spending, it can be helpful to refer to crime

statistics—figures that traditionally justify public

spending on police. Hawaii’s crime rates are much

lower than the rest of the country, with a violent

crime rate two thirds that of the United States as

a whole.

106

Since 1985, the level of property crime in Hawai‘i

has been on a general downward trend and

the level of violent crime has stayed largely

consistent, and small compared to the number of

arrests overall. As Anthony Romero, Executive

Director of the ACLU National has noted, “[e]

very three seconds a person is arrested in the

United States. According to the FBI, of the 10.3

million arrests a year, only 5 percent are for

offenses involving violence. All other arrests are

for non-violent offenses — these include many

relatively minor infractions like money forgery,

the alleged crime that the cops who killed

County

Police Department

Operating Budget

FTE

Cost of a Police

Ofcer

Honolulu

George Floyd arrived to investigate; or selling

single cigarettes without a tax stamp, the crime

Eric Garner lost his life for; or for marijuana or

other drug possession.”

107

Policing costs the counties half a

billion dollars.

Across Hawai‘i, counties are spending about

$124,000 per police officer each year, coming to

over $490 million in total expenditures on policing

(Table 2).

108

Kaua‘i County publishes more detailed

information about expenditures and revenues

than the three other counties. This financial

transparency allows greater insight into how

more accurate

Table 2

ACLU of Hawai‘i

police department expenditures are distributed

(Figure 7).

Overtime and benefits add to police departments’

bills on city budgets. The Honolulu Police

Department spent nearly $40 million on overtime

in fiscal year 2020 and is expected to spend $34

million by the end of fiscal year 2021.

109

Overtime

has been abused by hundreds of Honolulu police

officers.

110

This use of overtime brings the county’s

total operating budget closer to $350 million and

increases the average cost of a police officer to

$130,000. In addition to simple abuse of overtime,

Honolulu officials have also expressed concern

about spending related to pensions for retired

police officers and the possibility that some

employees use overtime to boost their retirement

pay.

111

Sweeps are costly.

111

Honolulu spends at least $4.8 million per year on

formal sweeps that displace unhoused individuals,

incur economic, physical, and psychological harm,

and do nothing to address the root causes of

houselessness.

Opportunities to Reivest in

Community

Investing in solutions to support houseless

individuals instead of policing can help address

the problems related to houselessness that

members of the public care about, such as

sanitation, while also saving the public money in

criminal legal system and healthcare savings. In

this way, supportive services can have a positive

multiplier effect. For example, it costs $72,000

112

to incarcerate one person at Oahu Community

Correctional Center per year—about three times

the cost of offering a person or family supportive

housing for the same time.

113

By providing

an unhoused person with supportive services

instead of incarcerating them, the public can

112

Figure 7: Kaua‘i Police Department General Fund Expenditures, FY 20

Employee & Related

Kaua‘i Police Department General Fund Expenditures

Employee & Related Breakdown of Expenditures

ACLU of Hawai‘i

enjoy tens of thousands of dollars in savings.

Unhoused individuals also must often rely on

emergency health services, which can cost the

public thousands of dollars per visit. Individuals

who receive housing services are less likely to

use the emergency room or be admitted to a

hospital, resulting in cost savings for taxpayers.

The following section highlights some of the ways

Hawai‘i could be addressing houselessness and

saving money, instead of sinking resources into

criminalization.

1. Increase Housing First Vouchers

• With the resources spent on just one police

officer, Honolulu could provide 4 Housing First

vouchers providing housing and supportive

services for a year to 4 households and saving

taxpayers an estimated $45,984 per year

in costs related to healthcare, arrests, and

incarceration (Table 3).