2023

A FIRST LOOK

Chicago Resilient

Communities Pilot

Francisco Brady

Melinda Croes

Shantá Robinson

Misuzu Schexnider

Stephen Stapleton

Nola Wallace

First Look Report

Letter from the City

My administration has been committed from day one to reversing the historic economic

injustices that underlie poverty and violence in Chicago by investing in our City's residents. Too many

communities have been overlooked for far too long, and I, along with Commissioner Brandie Knazze

from the Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS), are working to ensure these injustices

are eradicated across our city.

Thanks to investment decisions we made in the Chicago Recovery Plan, Chicago has been able

to implement cutting-edge initiatives to support an equitable recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Chicago Resilient Communities Pilot (CRCP), one of these innovative initiatives, aims to reduce

poverty by putting cash directly in the hands of people who need it the most.

In 2022, DFSS worked with non-profit partners to implement one of the largest publicly-

funded cash assistance pilots in the country. With input from an advisory council of experts and

community members, the program was built upon strengths-based philosophies that put participants

front and center.

Since June of 2022, we have provided monthly $500 checks to more than 5,000 Chicago

residents, giving households the flexibility and choice to determine how to best meet their needs and

personal goals.

Through the CRCP, we hope to enable Chicago residents to address their immediate financial

needs and to gain the breathing room needed to invest in education, employment, and other self-

directed pathways to the greater well-being and success that they deserve. Thanks to our partnership

with the University of Chicago Inclusive Economy Lab, we are gathering new and unique insights that

will impact the national conversation on the outcomes of cash assistance, providing insights for

policymakers and advocates across the nation to build a stronger and even more effective safety net,

and help civic leaders reimagine how we enable hard-working people thrive.

The pandemic opened the door for all of us to advance visionary strategies to build healthier

and more resilient communities, and we look forward to this ongoing research as we continue to build

a stronger foundation for Chicago by better supporting all Chicago residents.

Sincerely,

Mayor

Commissioner

3

A FIRST LOOK: CHICAGO RESILIENT COMMUNITIES PILOT

Glossary

ADMINISTRATIVE DATA

Administrative data is the data governments

and other organizations collect about the

people they serve. This can include demo-

graphic, financial, and workforce information

through organizations such as the Illinois

Department of Human Services, the credit

bureaus, and other organizations.

APPLICANT POOL

Those who were randomized and consented to

research (6,237 people).

CONSENTED TO RESEARCH

A process through which applicants indicate

whether they wished to participate in

research activities. Data in this report come

only from study participants who consented

to research. Participation in research was

not a condition for receiving the monthly

cash payments.

CONTROL GROUP

The set of applicants who applied for and are

eligible for the program but were not assigned

to receive funds (3,624 people).

ENROLLED TREATMENT GROUP

The set of applicants who are receiving

the monthly $500 cash payments (2,613

people). This group is sometimes referred

to as enrollees.

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

The set of applicants from both the

treatment and control groups who consented

to participate in research activities (6,237

people). This group is sometimes referred to

as participants.

QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Research that relies on primary data obtained

by the researcher through interviews, obser-

vations, or focus groups.

QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH

Research that focuses on collecting and

analyzing numerical data.

4

UCHICAGO INCLUSIVE ECONOMY LAB

Executive Summary

Chicagoans aspire to take care of their families, contribute to their communities, and pursue their

dreams. However, racial segregation and disinvestment in our city have left many of our neigh-

bors without the resources to reach these goals. Exclusionary government policies and institutional

practices have prevented many families from accumulating enough wealth to make their preferred

choices about what to eat, where to live, where to work, and how to raise their children. The COVID-19

pandemic exacerbated these longstanding challenges, especially for Chicagoans of color.

To support an equitable economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, Mayor Lori Lightfoot and

the City of Chicago’s Department of Family and Support Services launched the Chicago Resilient

Communities Pilot (CRCP) in April 2022. The CRCP is a $31.5 million investment designed to provide

$500 monthly payments for one year to 5,000 households. The pilot was open to all Chicago resi-

dents who are at least 18 years old, reside in a household with an income less than 250 percent of the

Federal Poverty Level (FPL), and experienced hardship due to COVID-19. Priority was given to

applicants living in poverty and in communities experiencing pre-existing economic hardship.

This First Look report describes who applied to the CRCP, what their stated needs, goals, and priorities

were prior to the pilot starting, as well as any physical or mental health concerns. It also captures the

participants’ experiences from qualitative interviews which are interspersed throughout this report.

“

It’s so crazy how it all happened. When I found out about it, I was out at dinner with my

best friend and we were talking about making ways and I got a text message and it said,

‘Congratulations! You have been selected to participate in the Chicago Resilient Commu-

nities program!’ I instantly started crying because, you know, I had taken so many losses

in the past years…It finally felt like it’s my time…I was literally just getting out of eviction

from the pandemic because I was unemployed. I work in the hospitality industry…and it’s

been pretty hard.

To have extra income for an entire year is a blessing. I don’t have to worry about being

behind on rent or being behind on my car or light bill or whatever the case may be because

I will always have that extra money to fall back on to feed me.

”

DARRIEN, AGE 33

1 See 2022 Poverty Guidelines: 48 Contiguous States (all states except Alaska and Hawaii).

2 Quotes have been lightly edited for clarity. Pseudonyms are used.

5

A FIRST LOOK: CHICAGO RESILIENT COMMUNITIES PILOT

At the request of the City of Chicago, the University of Chicago Inclusive Economy Lab is employing

a mixed methods approach to evaluate the impact of this pilot across a number of outcomes of

policy interest. The evaluation focuses on four broad categories:

• Financial stability, including credit scores and accounts in delinquency;

• Economic mobility, including labor force participation, wages, and educational attainment;

• Well-being, including physical and mental health, food security, and housing security; and

• Sense of agency, as measured through validated survey instruments.

As anticipated, the CRCP had more applicants than spots available. To ensure equity and fairness,

the Inclusive Economy Lab conducted a lottery to randomly select 5,000 participants for the pilot.

The random assignment to receive cash created an ideal set up for our research team to isolate

the impact of the pilot through a randomized controlled trial (RCT), the “gold standard” in evaluation.

By comparing the outcomes of those who were offered the $500 monthly payment through the lot-

tery (the treatment group) to those that were not (the control group), researchers can confidently

determine that any differences in outcomes between these groups is attributed to the CRCP. The

research team also launched a qualitative study that will enrich the quantitative findings from the

RCT by examining the impact of the pilot in participants’ own words.

All the data presented in this report are pulled from the CRCP application and are only data of

applicants who consented to participate in the research study. To understand who applied to the

pilot, this report will present baseline demographics, disaggregated when appropriate, by age, care-

giver status, income, and economic hardship index.

These preliminary insights are intended to help stakeholders understand the needs of the

study participants at the time of the application and are not intended to draw any conclu-

sions about the impact of the CRCP. Research findings on various outcomes will be shared in

subsequent reports after the pilot and analysis of administrative data, survey data, and qualitative

interviews have concluded.

Executive Summary Continued...

3 Economic Hardship Index is based on the Great Cities Releases Updated Hardship Index for Chicago Community Areas and 2020 Census data.

6

UCHICAGO INCLUSIVE ECONOMY LAB

In interviews, enrollees said they commonly experienced significant financial hardship and cited the need

to make difficult financial decisions and balance financial obligations. In surveys taken at the time of

application, respondents ranked their top five needs and priorities for the next year as:

Preliminary Insights

Compared to all Chicagoans who were estimated to be eligible for the CRCP, the enrolled treatment

group is:

• slightly younger,

• more likely to identify as female and to have children,

• more likely to identify as Black or African American, and less likely to identify as Hispanic,

• more likely to be employed, but earn significantly less than average, and

• more likely to experience housing instability.

Study participants expressed concerns about their physical and mental health.

• Over one in four respondents (27 percent) reported that their physical health was not good for at

least three weeks of the last month.

• Of respondents 65 and older, 44 percent indicated that their physical health was not good for more

than two weeks of the last month.

• One in three respondents (33 percent) reported that their mental health was not good for more than

two weeks of the previous month. This is far higher than what is observed in the general adult popu-

lation under 250 percent of the Federal Poverty Level, where only six percent receive scores placing

them in the range associated with severe psychological distress in 2021.

• When analyzing mental health by age, 39 percent of respondents ages 18-29 report similar

mental health concerns, compared to 23 percent of respondents over 65.

• Caregivers of adults indicate the highest level of mental health concerns at 41 percent.

ABILITY TO

PAY BILLS

PAYING OFF

DEBTS

SAVING

MONEY

FINDING A NEW

PLACE TO LIVE

FINDING A NEW

JOB/PROMOTION

4 The Chicago population estimated to be eligible for the CRC is based on ACS 5-year respondents age 18 or older in households beneath 250 percent of the

Federal Poverty Level in Census estimates from 2016-2020. See Table 1.

5 The demographic terms used in this report are those used in the application.

7

A FIRST LOOK: CHICAGO RESILIENT COMMUNITIES PILOT

The City received more than 176,000 applications for

the pilot, while having just 5,000 slots available. After

a preliminary eligibility review and removal of duplicate

entries, 150,101 applicants remained. A two-part lottery

process was then conducted, with all applicants being

placed in an initial lottery where 11,915 applicants were

randomly selected. The second lottery then randomly

selected 5,000 of these applicants who were invited to

enroll in the pilot. The remaining 6,915 households were

assigned to the control group. The remaining 7,000

control households were given a number on the wait-

list. The lottery was designed to prioritize households

living in poverty and those living in communities with

pre-existing economic hardship.

A total of 620 households were unable to enroll in the

pilot study because they were ineligible (20), moved out

of the city (one), opted out (17), did not complete the en-

rollment paperwork in the required timeframe (574), or

were unresponsive (eight). Unfilled slots went to the next

person on the waitlist. Ultimately, 5,006 people enrolled.

The demographics of the enrolled treatment group very

closely mirror those who were offered the program but

did not enroll and the entire applicant pool.

The application for the CRCP asked all applicants if they

wished to participate in research activities. Applicants

were informed that their response to this question would

not increase or decrease their chance of being selected

for the pilot. A total of 6,237 study participants who

consented to research (2,613 treatment and 3,624

control) will be the focus of this and future reports.

Application Pool

and Participant

Selection

How the CRCP Study

Participants Were Identified

ELIGIBLE

APPLICANTS

150,101 individuals who applied

for CRCP and were eligible

RANDOMIZED

APPLICANTS

11,915 applicants who

were randomly selected for

the lottery pool

LOTTERY TO

ASSIGN APPLICANTS

5,006

(2,613 CONSENTED

TO RESEARCH)

3,624

ENROLLED IN TREATMENT

CONSENTED TO RESEARCH

Assigned to

Treatment:

5,000

Assigned to

Control:

6,915

88

9

“

What influenced my decision [to apply]

was the fact that I know that I needed

some things. I needed more income,

more money. I knew I did. Like I said, I

pay for medication. Just to get around

and for my house, help me with my

bills. I have medical bills because I’m

not insured, and I have medical bills

that I’m paying slowly but surely...I

was just saying to myself that the first

thing I’d do, no matter the cost, is I’d

get myself some new glasses.

”

TIM, AGE 62

The research team also randomly selected 302 participants who consented to research for

the qualitative research. Of these participants, 130 people (111 from the treatment group and

19 from the control group) participated in semi-structured qualitative interviews. During

the qualitative interviews, study participants shared their experiences living in Chicago, their

reactions to the pilot, and how they hope participation in CRCP will impact their lives.

A sample of these narratives are interspersed throughout this report.

“

Somebody told me about this program,

and [said] ‘I think it would help you

out a lot even though sometimes you

don’t want to admit you need help.’ It’s

not that I have a big ego or pride, it’s

just, I look at it like, ‘Okay, I went back

to work, maybe because I’m at work,

somebody that lost their job might

benefit more from it…So I try to give

other people a chance, people that

really need it.’ But [my friend] called

me, ‘I know you need help, fill out that

application…’ I’m like, ‘I don’t know….

maybe I don’t qualify.’ But then, anoth-

er friend of mine, ‘Did you fill out the

application? Because you know this

can help us.’ I said to myself… ‘I‘m a fill

out the application, see if I qualify’…I

glanced over it, and I was like ‘Sounds

like me’…[When] they told me I was

selected…I [couldn’t] believe it, I never

win anything.

”

SARIN, AGE 43

6 There is slight variation in application numbers and data from previously published media due to changes in the participant pool (moving away, death, and other factors).

The data shared is current as of Oct. 12, 2022.

7 Applicants may have been ineligible due to not living in the City of Chicago or earning above the target income.

8 Some selected participants did not enroll in the pilot and were replaced with people on the waitlist. Due to the unpredictability of participant uptake, 5,006

households instead of the target of 5,000 were enrolled in the pilot. This possibility was budgeted for.

9 The Inclusive Economy Lab will share additional information about the pool of applicants and study participants in its Process Evaluation Report,

scheduled for Spring 2023. See Table 3 in the Appendix for demographic profiles of the CRCP lottery and enrolled treatment participants.

10 Future research reports that will focus on outcomes will utilize the full study participant group population that consented to research: all of those offered the program

(the treatment group) and the control group.

11 Semi-structured interviews are formal conversations wherein the researcher follows a prepared list of questions or topics, while also maintaining

flexibility to follow the topical trajectories as appropriate. This method also allows the interviewee freedom to express their views on the topic in their own terms.

9

UCHICAGO INCLUSIVE ECONOMY LAB

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of all Chicago households who were estimated to be

eligible for the pilot, the applicants included in the lottery, and the applicants who consented to research

and ultimately enrolled in the study.

Compared to all Chicagoans estimated to be eligible for the pilot, members of the enrolled treatment group

are slightly younger (average age of 41), more likely to be female (72 percent are female), more likely to have

children, more likely to identify as Black or African American, and less likely to identify as Hispanic.

CRCP enrollees resemble the full lottery pool of applicants, suggesting that the steps needed to enroll in

the pilot did not affect the demographic makeup of the treatment group that ultimately received the cash

assistance. Ongoing research will explore what led to the success in recruiting from these demographics as

well as what may have led to lower participation from other populations.

INCOME

The Chicago Resilient Communities Pilot is targeted to households who earn less than 250 percent of the

Federal Poverty Level (in 2022, $33,975 for an individual, $57,575 for a household of three). Table 1 shows

that the average enrolled household earns $15,319, well below the income eligibility criteria and less than

half of the average income among eligible households. Almost 64 percent of households earn significantly

less and are under 100 percent of the FPL ($12,880 for an individual, $21,960 for a household of three).

Thirty-six percent of enrolled treatment participants earn between 100 percent and 250 percent of the

Federal Poverty Level, mirroring the applicant pool.

Demographic Prole

of Individuals Who

Consented to Research

A FIRST LOOK: CHICAGO RESILIENT COMMUNITIES PILOT

12 Census estimates are derived from IPUMs ACS 5-year estimates for PUMAs within Chicago 2016-2020, adjusted to match the FPL distribution of the sample

(see https://usa.ipums.org/usa).

13 The enrolled study participants are balance tested and share the same characteristics as the applicant pool. Additional information regarding the

demographic breakdown at each phase of randomization will be shared in the Process Evaluation, scheduled for Spring 2023

14 Incomes of enrolled treatment participants are slightly lower than the average applicant in part because lower-income households were given a slightly higher chance

of being selected for the pilot.

“

...I am so happy about this program…I don’t have to worry about my financial issues any-

more and I can focus on something that’s gonna push me ahead in the future. Something

that’s gonna benefit, like, it’s not gonna benefit me right now, but it’s gonna benefit me in

the long run, which would be going back to school.

”

DANICA, AGE 23

10

UCHICAGO INCLUSIVE ECONOMY LAB

Category Eligible CRCP Census Estimates

b

Applicant Pool Enrolled in Treatment Group

n 786,924 6,237 2,613

Age 45 41.7 41.5

18-29 28.4% 22.4% 22.2%

30-64 52.8% 70% 70.5%

65+ 18.8% 7.7% 7.3%

Female 55.9% 70.1% 71.6%

Male 44.1% 28.5% 27.1%

Nonbinary or Other N/A 1.3% 1.2%

Household Size 2.8 2.4 2.4

Any Children 30.2% 57.2% 58.1%

Number of Children 0.6 1.2 1.2

Black or African American 40.1% 69.8% 70%

White 39.3% 15.3% 15.9%

American Indian or Alaska Native 1% 2.7% 2.7%

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander 0.1% 0.7% 0.8%

Asian 7.1% 2.4% 2.2%

Race Other 16.4% 11.7% 11.7%

Hispanic 33.8% 23.4% 23.3%

Not Hispanic 66.2% 76.6% 76.7%

Household Income $38,377.58 $15,239.78 $15,319.19

Below 100 Percent FPL 32.2% 63.6% 63.7%

Above 100 Percent FPL 67.8% 36.4% 36.3%

Employed 44.5% 52.7% 52.7%

No High School Diploma 23.1% 21% 19.9%

High School or GED 32.2% 35.4% 34.8%

Some College or Associates Degree 27.4% 33.5% 35%

Bachelors 12.2% 6.8% 7%

Masters 3.7% 2.2% 2.1%

Other Education N/A 1.2% 1.2%

Renter or Homeowner 97.2% 77.2% 77.4%

Housing Unstable N/A 14.2% 13.5%

Homeless N/A 3.9% 3.9%

Table 1

|

Demographic Profiles for Eligible Chicago Population and Those Consenting to Research

a

a Owing to data availability, statistics only include eligible applicants. Applicants may submit multiple responses to race/ethnicity.

b Census estimates are based on ACS 5-year respondents 18 or older in households beneath 250% FPL.

11

A FIRST LOOK: CHICAGO RESILIENT COMMUNITIES PILOT

EMPLOYMENT & EDUCATION

Enrollees in the treatment group were more likely than the average eligible household to be employed.

Although the vast majority (79 percent) of enrolled treatment participants held at least a high school degree

or equivalent, they were less likely to have an education beyond a high school degree. Table 1 describes that

at the time of application, 53 percent indicated that they were currently employed. Further research will be

conducted to better understand the employment and income sources of those participating in the research.

Many interviewees expressed the desire to improve their employment status through participation in the

pilot. Obstacles to obtaining or maintaining employment were a common theme in the qualitative inter-

views. For those who were employed, interviewees expressed interest in exploring options to enhance their

earnings, such as taking on more responsibilities in their current role, considering other employment oppor-

tunities, or investing in their education.

Of the interviewees who indicated they had difficulty maintaining or obtaining employment, nearly a quarter

identified the COVID-19 pandemic as a factor in their current employment struggles. Decreased or fluctu-

ating hours, loss of employment, being immuno-compromised, or having caregiving responsibilities impeded

many interviewees’ ability to work.

“

I had no idea that the job market [was so] tough...you have to work seasonally. And they

were paying 12 dollars an hour, part-time, and they required a college degree. That was a

huge shock for me. I don’t know how you’re supposed to finish college and go into that

with student loans.

”

DAVID, AGE 24

“

I was just recently having this, you know, little analysis… it is making me think about

these things, you know, value other things, [maybe I should] start thinking about myself,

because I recently want to see [if] I could basically go to school and get my master’s

degree…but then I don’t have the time, so I am like, I need to find myself time to, you know,

reach my goals so that I can feel accomplished as a woman, as a mother, as a daughter,

you know, and just for myself.

”

CARRIE, AGE 40

“

I have done lost people to the pandemic, through COVID, through gun violence. It has

affected me with my bill history, pushing me back on my bills…I had to quit my job

[during] the pandemic because my daughter, she has a disability, and she has a very weak,

weak, weak immune system. It’s just like anything in the air she automatically gets sick…

It’s certain people knowing they be sick, but they still shake your hand. Certain people

know that they’re sick, but they still be in your face without a mask on. It’s very tricky and

very risky…Basically, that’s really what set me back, the COVID.

”

DIANA, AGE 33

12

UCHICAGO INCLUSIVE ECONOMY LAB

HOUSING

At time of application, 77 percent of the enrolled treatment group indicated that they are a renter or home-

owner, which is lower than the rate for all Chicagoans eligible for the pilot (Table 1). Four percent of enrollees

are homeless, and 14 percent are housing unstable.

In the qualitative interviews, many participants expressed that they would like to use money received from

CRCP to repair their home, purchase a home, or establish a stable housing situation. This is supported

through the quantitative survey, where 31 percent of respondents indicated that finding a new place to live

is a priority.

Others indicated that this opportunity would allow them to alter their housing situation to be more

comfortable by moving closer to family, moving to a more affordable or safer area, or finding better living

accommodations overall.

15 Applicants were asked to indicate which of the following best describes their housing status: a) I rent or own my home or apartment b) I live permanently with others and do not pay

rent c) I move frequently from place to place d) I am experiencing homelessness e) I have recently exited an institution I was staying in and have no stable housing at this time (jail,

prison, foster home, nursing home, medical center, substance use facility) or f) other. Responses are defined as follows: “homeless” includes those who selected d, “housing

unstable” is defined as either b, c, or e.

“

My house situation is awful. It’s absolutely awful. And that would definitely be something

that could change…God knows it does. And I am, I am at my wit’s end…it’s falling apart.

And, you know, [we had] a furnace that wasn’t working during the wintertime, and you

could see the ice on the walls. We got little heaters and stuff, but that is not, you know…I

don’t want another year [to go by like this] and that’s just what I mean, I’m not even

kidding.

”

ALICE, AGE 49

“

I was thinking about saving that money. Just so I can put [it] towards a property, and in

the meantime, while I’m receiving the money, work on my credit. That way I can boost

my credit and be able to actually purchase a home where I could stick my mom and my

grandmother and be able to take care of them and return that favor that they’ve done for

me while I was growing up.

”

RHONDA, AGE 31

13

NEEDS AND PRIORITIES

The freedom and simplicity of guaranteed income programs—that participants can use the payments in the

ways they deem best—also means that the impact of guaranteed income programs can be difficult to iso-

late, as the impact can dissipate across many different outcomes. The research team asked applicants to

identify their top needs and priorities to ensure that future quantitative impact analyses focus on outcomes

that study participants themselves believe to be most important. Applicants have many different goals

for how they might use an additional $500 a month due to their personal situations and their life circumstances.

“

Money is very important. When I’m budgeting, cause I’m on a fixed income, [money’s]

all I think about….What am I gonna do? Like I said, $500 for, for a month, would’ve come

in really handy because now [her granddaughter] gonna [continue her education]…[but

the] fee is just, it’s just enormous. So now, I think about all those things when it comes to

money. Just gettin’ us our household needs. Toiletries, and all these things gotta come out

of cash. It’s just…kinda like a balancing act. Where do I need more, most?

”

FAITH, AGE 58

16 Baseline survey data is only presented for eligible applicants who consented to research and completed the survey. The number of survey respondents varies by question.

17 Specifically, researchers will construct a participant-specific index that weights responses to questions related to their top needs and priorities more heavily. For example, if study

participants report that “getting health, dental, or mental health care” is their top priority, then data related to access to and use of medical care, and physical and mental health

outcomes, will receive higher weight in the index. In this way, researchers can measure whether the pilot helped make improvements in areas prioritized by study participants.

A FIRST LOOK: CHICAGO RESILIENT COMMUNITIES PILOT

Survey Responses

The CRCP application included optional research questions to understand applicants’

needs and priorities for the next year, their self-reported physical and mental health,

and the existence, if any, of psychological distress. Responses establish a baseline

for the well-being outcomes that are of interest to the City of Chicago for this pilot.

The research team will conduct subsequent surveys during the pilot to identify any

changes in respondents’ physical and mental health. Future surveys will also cover topics

such as COVID-19 impacts, financial well-being, food security, employment, housing, and

transportation, among other things.

14

UCHICAGO INCLUSIVE ECONOMY LAB

Figure 1 | Study Participants’ Self-Reported Needs and Priorities at Baseline

Able to pay bills

Paying off debts

Finding new place to live

Finding a new job/promotion

Reducing stress and anxiety

Buying things I need (e.g. food)

Getting health, dental, or mental care

Buying things for children

New car/repairs

Finishing education/more training

Helping my family members

Helping my community (e.g. church, neighborhood)

Growing my family

Finding ways to relax/have fun

Improving romantic relationships

% Applicants Reporting

Priority Rank

Top Priority Other Priority

Applicants were asked to rank their top three needs and priorites over the next year

Baseline survey data is only presented for eligible applicants who consented to research (n=5,492)

0 20 40 60 80

Figure 1 displays the top priority and the second and third priorities, defined as “other priority,” for study

participants over the next year. In order, the top five areas reported as highest priority were the following:

• Ability to pay bills was, by far, the highest priority for study participants with 68 percent selecting it

as one of their top three priorities.

• Paying off debts and saving money were tied as the second and third most important priorities, with

33 percent of study participants ranking each as a top three priority.

• 28 percent of respondents who earn between 0 to 100 percent FPL ranked paying off debts in their

top three priorities while 41 percent of those earning between 101 percent and 250 percent of the

Federal Poverty Level are more likely to prioritize paying off debts.

• Finding a new place to live was in the top three priority list for 31 percent of study participants.

• Finding a new job/promotion was also a high priority, with 24 percent of respondents indicating this

is in their top three priorities.

Saving money

15

A FIRST LOOK: CHICAGO RESILIENT COMMUNITIES PILOT

NEEDS AND PRIORITIES BY AGE

18

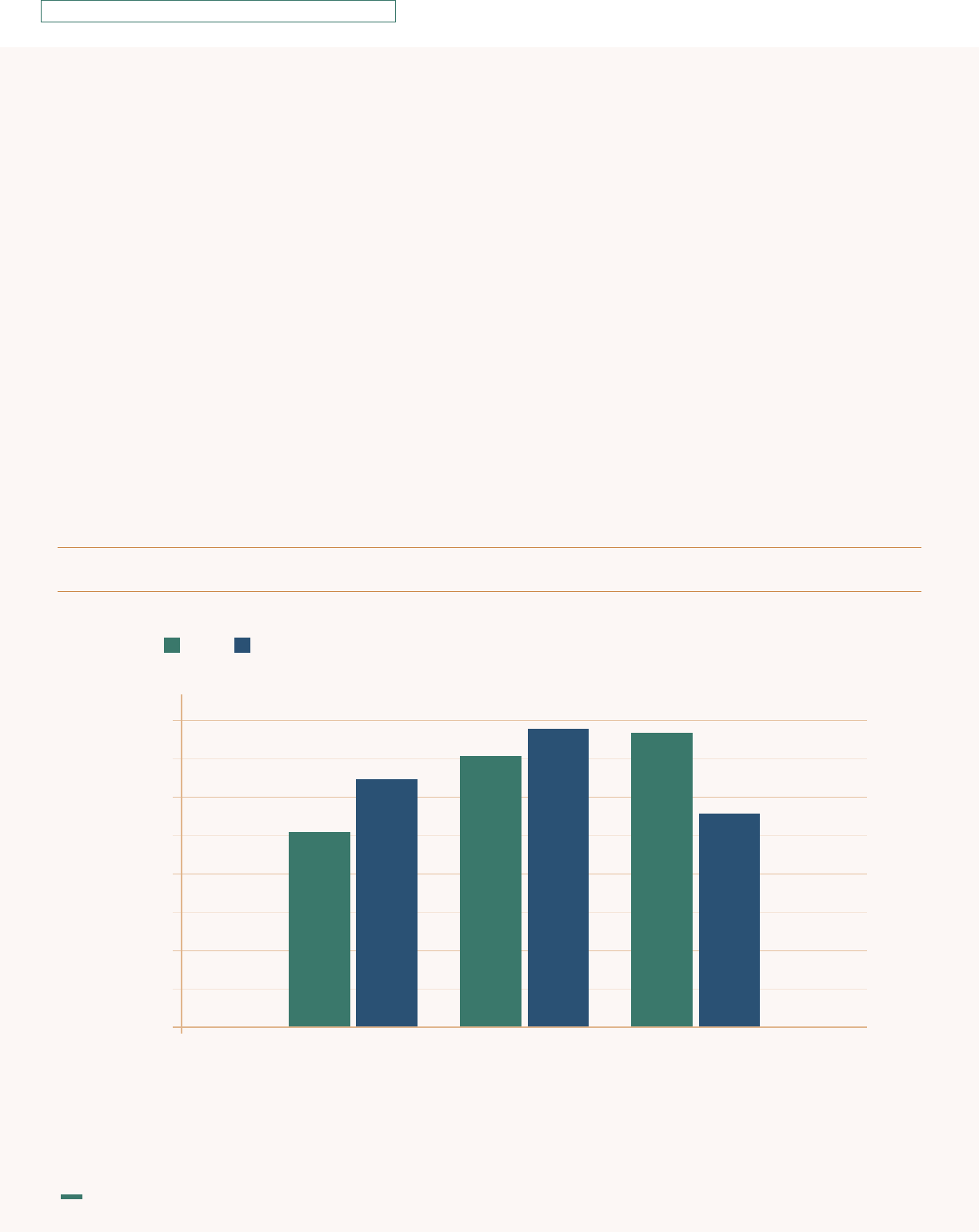

While the ability to pay bills was the highest priority for study participants regardless of age, the sub-

sequent top needs and priorities varied by age group. The 18-29 year old group reported the abil-

ity to pay bills most frequently (64 percent), saving money (38 percent), finding a new place to live (34

percent), paying off debts (30 percent), and finding a new job or promotion (25 percent) as their

highest priorities.

After the ability to pay bills (68 percent), study participants ages 30 to 64 reported paying off debts (33

percent), saving money and finding a new place to live (both at 32 percent), and finding a new job/pro-

motion (26 percent) as their top needs and priorities.

In the 65 years and older category, the highest need and priority was the ability to pay bills (78 percent),

followed by getting health, dental, or mental care (35 percent) and reducing stress or anxiety and

paying off debts (both at 34 percent). Buying things I need rose to the top five priorities (30 percent),

unlike for the other age groups.

“

I can’t work because I have, you know, medical issues and I don’t want to go downtown

on the bus and be exposed to [COVID]. Being in an office and people coming and going all

right, it’s just a nightmare…I can’t improve the quality of my living situation until I have

the income which can only be gotten through employment and right now employment is

not an option until COVID go away, I can’t feel safe about working and traveling.

”

KATHERINE, AGE 68

“

Money makes the world go ‘round. Money is the main source of how you do everything...But

how I think about money is, it’s like—you could save it, but it’s hard to save, because you have

bills and all those things, and then you have stuff that happens unexpectedly like car issues,

family issues, death in the family and stuff like that...that kind of hinders your financials.

”

ARIANA, AGE 31

“

The hope is to get a better job, to get a better house and buy stuff. Because everything

here in America, [most of] the time it’s money…it’s very hard for us. When you study

full-time, and you work part-time...it means you will not rest, you will not sleep well…As

[an] immigrant here you will not find no one who will pay your bills or who can help you. It

means you’re the only one fighting with all the world here.

”

MALIK, AGE 29

18 Differences by age, caregiver status, household income, and community level Economic Hardship Index were examined for baseline survey questions. Statistics are shared for

these subgroups only when notable.

16

UCHICAGO INCLUSIVE ECONOMY LAB

Figure 2

|

Needs and Priorities at Baseline by Age

Age: 18-29

Age: 30-64

Age: 65+

Able to pay bills

Paying off debts

Finding new place to live

Finding a new job/promotion

Reducing stress and anxiety

Buying things I need (e.g. food)

Getting health, dental, or mental care

Able to pay bills

Paying off debts

Finding new place to live

Finding a new job/promotion

Reducing stress and anxiety

Buying things I need (e.g. food)

Getting health, dental, or mental care

Able to pay bills

Paying off debts

Finding new place to live

Finding a new job/promotion

Reducing stress and anxiety

Buying things I need (e.g. food)

Getting health, dental, or mental care

% Applicants Reporting

Applicants were asked to rank their top three needs and priorites over the next year

Baseline survey data is only presented for eligible applicants who consented to research (18-29 n=1,287; 30-64 n=3,817; 65+ n=388)

0 20 40 60 80

0 20 40 60 80

0 20 40 60 80

Priority Rank

Top Priority Other Priority

Saving money

Saving money

Saving money

17

A FIRST LOOK: CHICAGO RESILIENT COMMUNITIES PILOT

PHYSICAL AND MENTAL HEALTH IN THE LAST 30 DAYS

As part of the application, study participants answered questions about their physical and mental health

during the last 30 days as shown in Figure 3. While 32 percent report no physical health concerns and

25 percent report no mental health concerns, the remainder of study participants report some concern.

• 27 percent of study participants report that their physical health was not good for more than two

weeks of the last month.

• 33 percent report that their mental health was not good for more than two weeks of the last month.

Interviewees often raised physical health concerns and cited the toll the pandemic has taken on their

quality of life. Other challenges like rising prices, limited funds and access to resources, and insurance

coverage and eligibility gaps made it difficult for interviewees to address their physical health needs.

Many participants also identified the mental toll caused by health challenges, loss of family members, loss

of employment, loss of financial investments, political divides, and strains on already limited resources.

Figure 3

|

Poor Physical and Mental Health in the Last 30 Days

Applicants were asked how many of the last 30 days their mental and physical health was not good

10

0

20

30

40

% Applicants Reporting

No Days Less Than 2 Weeks More Than 2 Weeks

Baseline survey data is only presented for eligible applicants who consented to research (n=4,754)

Health Category

Mental Physical

18

UCHICAGO INCLUSIVE ECONOMY LAB

Figure 4

|

Poor Physical and Mental Health in the Last 30 Days by Age

Applicants were asked how many of the last 30 days their mental and physical health was not good

No Days Less Than 2 Weeks More Than 2 Weeks

10

0

20

30

40

10

0

20

30

40

% Applicants Reporting

Physical

Mental

18-29 30-64 65+

Baseline survey data is only presented for eligible applicants who consented to research (18-29 n=1,086; 30-64 n=3,313; 65+ n=355)

“

An unfortunate thing [happened] to me. Uhm, my kids’ mother died last year, in July. So,

it’s been a struggle since then. It’s just me [and] them…Both of my parents passed, both

my sister and my grandmothers. Everybody’s gone, basically. It’s just us. So, I was so

happy to get accepted into the program because every little bit helps. I’m currently trying

to, like, keep my health up and all, because I have a few things going on…So, I’m trying to

get work and so forth, and so on, but I’m fighting that battle first, in order to get right…

All I have is them, and all they got is me.

”

FRANKIE, AGE 59

PHYSICAL AND MENTAL HEALTH BY AGE

Figure 4 shows responses to physical and mental health questions by age groups. Poor physical health

was reported by 19 percent of participants ages 18 to 29 years old. Older study participants reported the

highest rates of poor physical health of all age groups, with 44 percent of those 65 and older indicating that

their physical health was not good for at least three weeks of the last month.

Age

19

A FIRST LOOK: CHICAGO RESILIENT COMMUNITIES PILOT

PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS IN THE LAST 30 DAYS

The optional survey in the CRCP application used the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6+) to assess

study participants’ mental health. The K6+ is an established, widely used screening tool that quickly iden-

tifies psychological distress with six questions about how often in the last 30 days the respondent felt

nervous, hopeless, restless or fidgety, so depressed that nothing could cheer them up, that everything was

an effort, and worthless. The total score for the scale is computed by summing the points for the six ques-

tions. Those who score 13 or higher are classified as experiencing severe psychological distress. The CRCP

sample is compared to populations surveyed as part of the 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).

Figure 5 shows that almost four percent of the NHIS sample reported K6+ scores indicating severe

psychological distress in 2021 and six percent of those under 250 percent of the FPL experience severe

psychological distress. Of study participants, 33 percent indicated severe psychological distress, far

higher than the comparable national population.

Figure 5

|

Comparative Levels of Severe Psychological Distress of CRCP Participants

Applicants were rated using the Kessler scoring system on six questions

Baseline survey data is only presented for eligible applicants who consented to research (n=5,649)

% Reporting Severe Distress

0 5 10 15 20 3525 4030 45 50

General U.S Population

<250% FPL U.S. Population

CRCP Participants

“

[There’s] health stuff. Like, my mom [getting] sick, and I have to take care of her. Or my

son [getting] sick a lot as well and I have to stay at home to be with him, and take care of

him, and help him with school. So yeah, just health overall. And maybe, um….how do you

call that? Motivation. Maybe I got a little depressed and I want to do stuff, but I just don’t

have the energy to do it.

”

AMBER, AGE 28

19 The general U.S. Population is calculated from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey. The research team will explore why the percentage of those in the CRCP is higher than the

national sample. Contributing factors may include when the survey was administered (Spring 2022) when inflation was rising and the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. It

may also be that those under severe sample distress were more likely to seek out and apply for the guaranteed income pilot.

20

UCHICAGO INCLUSIVE ECONOMY LAB

Figure 6

|

Psychological Distress in the Last 30 Days by Category

Response Options:

None of the time A little of the time

Some of the time Most of the time All of the time

Applicants were asked how often in the last 30 days they felt:

Baseline survey data is only presented for eligible applicants who consented to research (n=5,649)

% Applicant Responses

0 10 20 30 40 7050 8060 90 100

Nervous

Hopeless

Restless/Fidgety

Depressed

Everything was effort

Worthless

“

I have been on disability for mental health. And then, also, I have a pin in my hip, so phys-

ically, there are days when I need to use a walker, a wheelchair. So, yeah, I would say when

my health isn’t good, everything kind of falls by the wayside as far as my goals and every-

thing. I have to reset. And then I have more doctor’s appointments and getting there and

back. So, it’s a lot to maintain my health and remain healthy. So yeah, I feel like that gets

in the way…[the] doctor’s office, it takes up a lot of energy, the system that we have.

”

MARY, AGE 34

Study participants who reported feeling distress most or all of the time during the last 30 days were most

likely to report that they felt “everything was an effort” (36 percent), “nervous” (31 percent), and “restless/

fidgety” (29 percent) as shown by Figure 6.

21

A FIRST LOOK: CHICAGO RESILIENT COMMUNITIES PILOT

Figure 7

|

Comparative Levels of Severe Psychological Distress of CRCP Participants by Age

Baseline survey data is only presented for eligible applicants who consented to research (n=5,649)

Applicants were rated using the Kessler scoring system on six questions

PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS BY AGE

Figure 7 shows that study participants ages 18 to 29 were more likely to experience psychological

distress than others surveyed. Thirty-nine percent of this group indicated psychological distress on the

K6+ scale, significantly higher than the national average of six percent for those earning under 250

percent. Thirty-one percent of study participants ages 30 to 64 indicated psychological distress compared

to seven percent. Similarly, of study participants ages 65 and older, 23 percent indicated psychological

distress compared to four percent nationally.

“

Wow, thinking about this makes you feel a little emotional. I’m thankful to God for what

I have. But I wish I did not have to decide between good and good. Do I decide to give my

son money for a football thing, or do I decide to give my [other] son money for college? I

have to decide which one is going to have [it]. Like, both of them are important…I don’t

know how to explain it, but I wish I didn’t have to do that. I wish I didn’t have to decide

stuff like that. I wish I could just go ahead and do it, get it done, [maybe] do something

for me.

”

LOLA, AGE 46

18-29

30-64 65+

10

0

20

30

40

35

25

15

5

50

45

% Redporting Severe Distress

Population

<250% FPL U.S. Population CRCP Participants

22

UCHICAGO INCLUSIVE ECONOMY LAB

Figure 8

|

Comparative Levels of Severe Psychological Distress of CRCP Participants by Caregiver Status

Baseline survey data is only presented for eligible applicants who consented to research (n=5,649)

*Data are not available for caregivers to adults in the general U.S. population

Applicants were rated using the Kessler scoring system on six questions

PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS BY CAREGIVER STATUS

Figure 8 indicates that 35 percent of those who are not caregivers have psychological distress compared

to the national survey where seven percent of those not caring for a child indicated psychological distress.

Those who are caregivers of children indicated 30 percent compared to the average of four percent. Care-

givers of adults in the study population were most likely to exhibit psychological distress, with 41 percent

scoring above a 13 on the K6+.

“

I’m the oldest of five.…So, I had to play the role of being a big sister, but also played the

role of mom. I cared for every single [one] of my siblings…. there’s times where my mom,

you know, worked third shift, um, whether I have to go to school the next morning. I was

in fifth, sixth grade, taking care of the newborn baby. Getting up in the middle of the night,

taking care of the baby.

”

LEAH, AGE 25

10

0

20

30

40

35

25

15

5

50

45

% Redporting Severe Distress

Caregiver for None Caregiver for Child Caregiver for Adult*

Population

<250% FPL U.S. Population CRCP Participants

23

A FIRST LOOK: CHICAGO RESILIENT COMMUNITIES PILOT

Summary

Chicagoans aspire to take care of their loved ones and achieve basic economic opportunity. The monthly

cash assistance offered through the Chicago Resilient Communities Pilot is a potentially powerful approach

towards stabilizing families and expanding economic inclusion, especially as it prioritizes households in com-

munities experiencing economic hardship and COVID-19 impacts. A first look at the 6,237 study partici-

pants reveals that their households experience considerable hurdles in meeting their daily needs, yet are

still striving for better, more stable futures.

The preliminary insights in this report present an opportunity to understand the material, physical, and

mental health needs of those who participated in the pilot across the city and to hear about the goals and

lives of study participants in their own words. Understanding the demographics and baseline needs and

priorities of those participating in this pilot reveal whether the pilot reached its target population and pro-

vide a glimpse into what Chicagoans need to achieve economic stability and success. Future analyses will

examine if and how the CRCP impacts employment, financial health, health, intrahousehold outcomes,

children, mobility, subjective well-being and agency, and social engagement and trust. Over the next several

years, the Inclusive Economy Lab will explore these short- and longer-term impacts of the pilot on partici-

pant outcomes through a mixed-methods evaluation that includes:

• Impact Evaluation: The team will identify the impact of this pilot by comparing outcomes for those

who are receiving the monthly cash transfers to those who are not through a randomized control trial.

The research team will analyze administrative data, quarterly surveys, and a final survey after the cash

transfers conclude.

• Qualitative Research: The qualitative research aims to elevate participant experiences in their own

words and provide additional context for the quantitative research. The qualitative research contains

three components: semi-structured interviews, a PhotoVoice project, and ethnographic observations.

• Process Evaluation: Through the process evaluation, the Inclusive Economy Lab will summarize find-

ings from focus groups, interviews, and application and survey data to better understand participant

and partner experiences with the pilot and generate best practices for future cash assistance and social

service programs.

The Inclusive Economy Lab looks forward to sharing findings from these evaluations over the coming years.

20 Intrahousehold outcomes refers to the spillover effects on others in the household.

21 PhotoVoice is a method used in qualitative research to understand an experience from a participant’s point of view. For this project, PhotoVoice is utilized by asking

participants to take photos about a different theme such as “joy” or “freedom” each month and provide captions for their photos. Select photos will be exhibited at

the conclusion of the pilot.

22 Ethnographic Interviews are a method of qualitative research that captures the daily lives of participants through direct observation within their homes and

communities. The aim of this research is to understand cultural context and experiences within participants’ day-to-day lives which cannot be captured through

interviews alone.

24

UCHICAGO INCLUSIVE ECONOMY LAB

Acknowledgements

The Inclusive Economy Lab would like to acknowledge several partners who played instrumental roles

in designing and launching the pilot and ensuring that as many eligible households as possible were

able to apply:

The City of Chicago and its Department of Family and Support Services with guidance from the Harvard

Government Performance Lab and the Mayor’s Office, along with its delegate outreach organizations—the

YWCA, Center for Changing Lives, Phalanx Family Services, Pui Tak Center, Spanish Coalition for Hous-

ing, and United African Organization; GiveDirectly, CRCP program administrator, and AidKit, their technology

partner; and the many organizations that jumped in to host in-person application assistance events or

shared the application with their networks. This work would not be possible without their support, and we

thank GiveDirectly for agreeing to share its data for use in this research and for public dissemination in this

report. Additionally, we would like to thank the University of Chicago Crown Family School of Social Work,

Policy, and Practice for their partnership.

We thank current and former Inclusive Economy Lab employees who contributed to this report:

Nour Abdul-Razzak, Ebony Scott Anderson, Carmelo Barbaro, Janelle Blackwood, Francisco Brady, Melinda

Croes, Misuzu Schexnider, Stephen Stapleton, Kim Tran, and Nola Wallace.

A team of diligent Principal Investigators direct this evaluation:

Alex Bartik (University of Illinois), Marianne Bertrand (University of Chicago), Sarah Miller (University of

Michigan), Elizabeth Rhodes (Open Research), Shantá Robinson (University of Chicago), and Eva Vivalt

(University of Toronto).

We would also like to acknowledge the work of the interviewers who made qualitative data collection

and analysis possible:

Chen Dang, Denisse Gonzalez, Eashaa Jampala, Nida Khafiyya, and Adam Leader-Smith.

This research was made possible in part by the generous support of:

Builders Initiative, Searle Funds at The Chicago Community Trust, The Rockefeller Foundation, W.K. Kellogg

Foundation, Polk Bros. Foundation, Joyce Foundation, PERT Foundation Impact Fund at the Chicago Com-

munity Foundation, Lloyd A. Fry Foundation, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, Pritzker Pucker Family Founda-

tion, Healthy Communities Foundation, Crown Family Philanthropies, Steans Family Foundation, and Pierce

Family Charitable Foundation.

The statements made and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the Inclusive Economy Lab.

25

The Inclusive Economy Lab partners with policymakers,

community-based organizations and others to generate

rigorous evidence that leads to greater economic

opportunity for communities harmed by disinvestment

and segregation.

inclusiveeconomy.uchicago.edu