Brigham Young University

BYU ScholarsArchive

,,9&2&2".%*22&13"3*/.2

Nature or Nurture in English Academic Writing:

Korean and American Rhetorical Paerns

Sunok Kim

Brigham Young University

/,,/63)*2".%"%%*3*/.",6/1+2"3 ):022$)/,"12"1$)*5J&%4&3%

"13/'3)& *.(4*23*$2/--/.2

9*29&2*2*2#1/4()33/7/4'/1'1&&".%/0&."$$&22#7 $)/,"121$)*5&3)"2#&&."$$&03&%'/1*.$,42*/.*.,,9&2&2".%*22&13"3*/.2#7".

"43)/1*8&%"%-*.*231"3/1/' $)/,"121$)*5&/1-/1&*.'/1-"3*/.0,&"2&$/.3"$3 2$)/,"12"1$)*5J&%4&,,&.!"-"3".(&,/#74&%4

$)/,"121$)*5&*3"3*/.

*-4./+"341&/141341&*..(,*2)$"%&-*$1*3*.(/1&".".%-&1*$".)&3/1*$",":&1.2 All eses and

Dissertations

):022$)/,"12"1$)*5J&%4&3%

Nature or Nurture in English Academic Writing:

Korean and American Rhetorical Patterns

Sunok Kim

A thesis submitted to the faculty of

Brigham Young University

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Arts

William Eggington, Chair

Cynthia Hallen

Troy Cox

Department of Linguistics

Brigham Young University

Copyright © 2017 Sunok Kim

All Rights Reserved

ABSTRACT

Nature or Nurture in English Academic Writing:

Korean and American Rhetorical Patterns

Sunok Kim

Linguistics, BYU

Master of Arts

For many years, linguists, ESL writing teachers, and especially students have puzzled

over the phenomenon where non-native English writers’ sentences are grammatically correct, but

their paragraphs and complete essays often appear illogical to native English speaking readers.

From the perspective of Kaplan’s original contrastive rhetoric theory where American rhetoric is

“linear,” Korean L2 writers’ apparently circular rhetoric causes problems. Even though Korean

writers are trying to write paragraphs that are logical for native English readers, this illogical

output results in Korean ESL students being perceived as poor writers. In order to discover more

about the nature of the rhetorical problems Korean ESL writers face, this study reports on a close

contrastive analysis of a corpus consisting of 25 Freshmen Korean ESL students’ unedited, first

draft essays and 25 Freshmen native-English speaking American Freshmen’ unedited, first draft

essays randomly collected from a series of 1st year writing classes at a U.S.-based university.

The analysis focused on areas where the logical flow breaks down from a native English reader’s

perspective. The Topical Structure Analytical approach (TSA), developed by Lautamatti (1987),

was used to analyze the data. Results show that both American and Korean Freshmen have

difficulty controlling topical subjects and discourse topics in their writing. Instead, they often

introduced irrelevant subtopics that did not advance overall topic development, making their

writing difficult for general readers to follow. The key finding of the study shows that to

overcome these rhetorical weaknesses, both Korean and American Freshmen need to be educated

in academic writing regardless of their first language.

Keywords: Intercultural Rhetoric, Academic Writing in English, Korean Language, Korean

Culture

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work would not have been possible without the support of professors. I am

especially indebted to Dr. William Eggington, Dr. Cynthia Hallen, and Dr. Troy Cox, my

committee members. They have provided me with extensive support, personal and professional

guidance and taught me much about scientific research.

I would especially like to thank Dr. Eggington, the chair of my committee. As my mentor

and ultimate role model, he has taught me more than I could ever give him credit for here. He

has shown me what a good teacher should be.

I am grateful to Dr. Hallen. She has provided me new perspectives toward my research

ideas with her creative thoughts. I especially appreciate her comprehensive feedback.

Dr. Cox gave me helpful suggestions. I also appreciate his guidance regarding a

quantitative approach to data analysis. His knowledge of statistics transformed this thesis.

I am especially grateful to my fellow students in the TESOL and Linguistics MA

programs in the department for their support, patience, and inspiration.

Most importantly, I would also like to thank my loving and supportive mother, younger

sister, Sun-Young and younger brother, Jin-kyu. My mother has sacrificed her life for her family

members, and she is always there for me.

Without the help of these professors, friends, and family, I would not have been able to

finish my study and this research would not have been possible.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITEL PAGE ................................................................................................................................... i

ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................... iv

LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... vi

LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... vii

LIST OF EXAMPLES ................................................................................................................. viii

Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1

Chapter 2: Review of Literature ..................................................................................................... 5

Korean Writing Patterns ..................................................................................................... 6

Coherence in Writing .......................................................................................................... 8

Topic Structural Analysis ................................................................................................... 8

Chapter 3: Features of Korean Language, Culture, and Academic Writing ................................. 11

Related grammatical features of the Korean language ..................................................... 12

Word order ............................................................................................................ 12

Omitting grammatical elements ............................................................................ 15

Miscellaneous ....................................................................................................... 16

Cultural differences ........................................................................................................... 17

Collectivism or harmonious culture in Korean culture ......................................... 17

Face, Politeness in Korean culture ........................................................................ 19

Inductive way of reasoning Vs. Deductive way of reasoning .......................................... 20

Academic writing .............................................................................................................. 22

v

Chapter 4: Methodology ............................................................................................................... 24

Research questions: ........................................................................................................... 24

Subjects ............................................................................................................................. 25

Three Paragraphs .............................................................................................................. 26

Reliability and Validity ..................................................................................................... 27

Lautamatti’s types of sentence .......................................................................................... 27

Lautamatti’s TSA and Simpson’s ESP ............................................................................. 28

Topic Sentences and Thesis Statements ........................................................................... 33

Deductive versus inductive problem ................................................................................. 33

Chapter 5: Results and Analysis ................................................................................................... 35

Identifying Topic Sentence and Thesis Statements .......................................................... 36

The Total number of Topics in the sentences ................................................................... 41

Topic Development Using the TSA Analytical Method................................................... 42

The Topical Structure Analytical approach (TSA) ........................................................... 48

Type of sentence ............................................................................................................... 50

Chapter 6: Discussion and Conclusion ......................................................................................... 60

References ..................................................................................................................................... 68

APPENDIX ................................................................................................................................... 72

vi

LIST OF TABLES

Table 5.1 Topic Sentence of Inductive & Deductive .................................................................... 37

Table 5.1.1 Each Student’ Topic Sentence Following an Inductive or Deductive Pattern ......... 38

Table 5.2 Thesis Statement of Inductive & Deductive ................................................................. 39

Table 5.2.1 Each Student’s Thesis Statement Following an Inductive or Deductive Pattern ..... 40

Table 5.3 Total Number of Sentences .......................................................................................... 41

Table 5.4 Total Number of Words................................................................................................ 41

Table 5.5 Total Number of Topic Subjects................................................................................... 42

Table 5.6 American Freshmen’ TSA and Korean Freshmen’ TSA .............................................. 48

Table 5.7 American Freshmen’ Topical Structure Analytical Approach (TSA) .......................... 49

Table 5.8 Korean Freshmen’ Topical Structure Analytical Approach (TSA) ............................. 50

Table 5.9 American Freshmen’ Type of sentence ........................................................................ 51

Table 5.10 Korean Freshmen’ Type of sentence ......................................................................... 51

vii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1 Five Cultural Rhetorical Patterns ................................................................................ 2

Figure 4.1 Summary of the Topic Structure Analytical Approach ............................................... 31

Figure 5.1 Discourse Topic Analysis of American No.2 Freshmen’s first paragraph ................ 44

Figure 5.2 Discourse Topic Analysis of Korean Student No.6’s a Paragraph ............................ 46

Figure 5.3 Discourse Topic Analysis of Example 4 ..................................................................... 47

viii

LIST OF EXAMPLES

Example 5.1 Korean Freshmen No.9’s a Paragraph ................................................................. 43

Example 5.2 American No.2 Freshmen’s a first paragraph ........................................................ 44

Example 5.3 Korean student No.6’s Paragraph .......................................................................... 45

Example 5.4 Korean Student No6’s Paragraph Rewritten by a professional native

English writer ......................................................................................................... 47

Example 5.5 American Freshmen’s quotation I .......................................................................... 53

Example 5.6 American Freshmen’s quotation I .......................................................................... 54

Example 5.7 Korean Freshmen’s quotation II ............................................................................ 55

Example 5.8 American Freshmen’s oral spoken discourse ......................................................... 56

Example 5.9 Korean Freshmen’s grammar mistakes .................................................................. 57

Example 5.10 American Freshmen’s grammar mistakes ............................................................ 58

1

Chapter 1: Introduction

As English has become a worldwide lingua franca, many Korean Freshmen attempt

to follow native English speakers’ language styles in speaking and writing. However, as

widely known, significant lexico-grammatical and writing style differences present

difficulties for many Korean English language learners. For example, a fundamental

tradition of the native English academic writing style is that it follows a linear logical

development where the writer is responsible for making meaning clear, following

Aristotelian deductive reasoning. On the other hand, the traditional Korean writing style is

based upon inductive reasoning where the reader takes responsibility for understanding the

writer (Eggington, 1987). As a native speaker of Korean and a learner of English as a

second language, I have personal experience with the rhetorical problems students may face.

Kaplan (1967) and other researchers claim that each culture’s rhetorical pattern

reflects the people’s logical preferences. After Kaplan analyzed English expository essays

written by ESL students whose native languages were Arabic, Korean, Japanese, Spanish,

and Russian, he then proposed a diagram (Figure 1.1) that represented five cultural

rhetorical patterns

1

.

1

A linear pattern for native English users, a parallel pattern for Semitic language users, an indirect pattern for

oriental language users, and a digressive pattern for Russian and Romance language users.

2

Figure 1.1

Five Cultural Rhetorical Patterns

According to Kaplan’s research, the English rhetorical pattern is depicted as

‘predominantly linear.’ This may be because the Western, or Anglo-American way of

thinking is affected by Aristotelian syllogisms

(Kaplan, 1967). However, the Oriental or

Asian pattern is a spiral as represented by the graphic form shown in Figure 1.1 above.

Initially, the rhetorical preferences portrayed in Figure 1.1 were generally accepted by

Western ESL teachers, linguists and researchers, but the concept has been challenged

primarily on cultural elitist grounds (Kubota and Lehner, 2004).

In response, other researchers assert that there do appear to be common patterns

based upon a set of similar experiences. For example, most recently, Grabe (2017) states

that:

In the last 15 years, in particular, I do not think that serious researchers come to

conclusions where, for example, all Chinese write a certain way because they have

had Chinese experiences and live in a Chinese culture. But there is no reason not to

explore carefully how prior educational experiences, cultural preferences, and other

national factors might generate patterns of variation that are less common or not as

pronounced in some other group of learners from a different L1 background or a

different country (Grabe, 2017: 125).

With respect to English, the general expectation is that an academic essay written in

English needs to present a clear purpose within a writer-responsible culture (Noor, 2001).

As such, English native readers expect to be presented with an explicit thesis and a direct

topic sentence early in the essay (Hinds, 1987). In addition, each paragraph is expected to

3

contain an early statement of its topic, and each sentence is expected to contain a related

topic subject, or the idea that the sentence is focusing on. As a result, the writer’s rhetorical

goal should be described clearly, straightforwardly, and efficiently (Kaplan, 1967).

However, as many previous studies have shown (Cho, J. H.A., 1999; Kubota and Lehner,

2004; Eggington, 1987), Korean freshman students in U.S. colleges, writing in English,

have transferred their preferred Korean rhetorical patterns into English.

From a Western reader’s perspective, these Korean preferences include an inductive

style with indirect topic development leading to a weak conclusion. Korean writer’s reader-

responsible writing style (Hinds, 1987) presents English native readers with more inferential

work to do such as decoding ambiguity, abstract ideas, and imprecise information.

Consequently, many ESL writing teachers, when they teach Korean Freshmen, stress

structuring essays with explicit theses and topic sentences (Choi, 2006; Choi, 2010; Ryu,

2006; Burns and Joyce, 2005; Vygotsky, 1978).

These findings suggest a need to examine the rhetorical problems Korean writers

face in academic writing, particularly in their freshman composition classes. This suggestion

leads to the following general research question: What are the major rhetorical development

problems that Korean ESL students face in freshman composition classes? This general

research question is then made more specific resulting in the following four research

questions.

1) What are the differences if any, between Korean Freshmen writing and American

Freshmen writing?

2) If there are differences, what are the major rhetorical development problems that

Korean ESL students face in freshman composition classes?”

4

3) If American Freshmen write in a linear way, is it natural or is the linear “logical”

frame a learned feature of academic writing in western culture?

4) Do American Freshmen write in a deductive style, while Koreans write in an

inductive style?

In order to answer these research questions, Korean and American Freshmen first

draft essays, all of which had no previous teacher edits, were analyzed with respect to their

rhetorical development. As will be seen below, both groups’ essays are written by writers

without long-term college-level training in academic writing, so there are frequent

coherence and cohesion weaknesses, and there are many grammatical errors. Most previous

related research has focused on more polished and edited essays, so the research results

from this present study provide insight into the unedited writing process of novice Korean

and American writers.

Before proceeding with the study, I will first present a review of relevant literature

regarding intercultural rhetoric studies in Chapter 2. This will be followed in Chapter 3 by a

discussion of linguistic and cultural differences between Korean and American writers with

a focus on Korean writers. I will then introduce the research design in Chapter 4. Chapter 5

will present the results and their analysis, and then a discussion and conclusion of the

research will be presented in Chapter 6.

5

Chapter 2: Review of Literature

As will be discussed below, the past decades have witnessed a major paradigm shift

in the teaching and study of academic writing for ESL students (Connor, 1987, 1996;

Eggington, 1987, Hinds, 1987). This shift was initiated by Kaplan’s article about cultural

thought patterns which argued that cultural preferences in rhetorical development influence

writing (Kaplan, 1966). Kaplan’s notion has contributed to our understanding as to why so

many ESL students struggle with rhetorical development in their writing in freshman

composition classes even after graduating from Intensive English Program (IEP) advanced

writing classes (Connor, 1987).

Among the wide range of international students studying at American universities,

Korean Freshmen seem to have particular difficulties in rhetorical development (Kaplan,

1966; Eggington, 1987; Noor, 2001; Connor, 1996; Hinds, 1987). Even when sentence level

grammar and word use is satisfactory, Korean Freshmen’ rhetorical development is often

labeled by instructors as “awkward,” “illogical,” and “lacking focus.” Unfortunately, many

learners do not know why their writing is judged as inadequate, so problems continue,

sometimes even after students finish freshman composition classes (Eggington, 2015:206;

Hinds, 1987; Connor, 1996).

According to the contrastive rhetoric studies cited above, there are learner variables,

cultural variables, and pragmatic variables that contribute to rhetorical difficulties in ESL

writing. However, these variables are difficult to isolate. In addition, there are differences

between writing pedagogy within an ESL tradition and writing pedagogy within a freshman

composition tradition (Moussu & David, 2015:50).

6

Korean Writing Patterns

Choi (2005) examined differences in Korean ESL students’ and native English

speakers’ writing regarding error types, textual organization, and cohesive devices. The

most significant difference was that the Korean ESL students wrote shorter essays. Also,

their writing showed more errors, more textual organization patterns, and less use of

cohesive devices. However, similarities in argumentative writing between the two groups

include a preference for a three-unit organizational structure (introduction, body, and

conclusion), as well as both groups using similar subcategories in each organizational type

such as claim, justification, and conclusion.

Kim (2008) explored the learning experiences of five Korean college ESL students

in U.S. college classes, and how they responded to required writing tasks. She focused on

differences between Korean and American cultures in communication, writing styles, and

classroom practices and how these differences influenced these students’ learning in

American university contexts. She indicated that the most influential contributor to both

positive and/or negative experiences was subjects’ perceptions of professors’ responses to

their writing. In addition, these perceived responses directly affected their students’

learning. According to study participants, for successful learning, students' effort should be

given priority.

Jung (2006) analyzed samples written by both Korean and American university

students. She also reviewed previous research on Korean rhetoric. This is because she

wanted to discuss the pedagogical role of Contrastive Rhetoric (CR) in bridging rhetorical

differences in specific EFL writing instruction for Korean Freshmen. In her literature

review, she found that Korean rhetoric is indirect, implicit, non-linear, mostly inductive,

7

specific-to-general, emotional, and reader-responsible. However, American rhetoric is

direct, explicit, linear, mostly deductive, general-to-specific, logical, and writer-responsible.

Xing, M., Wang, J., and Spencer, K. (2008) compared and contrasted five features of

contrastive rhetoric applied to English writing instruction in an on-line “e-course” program.

The first feature was inductive vs. deductive development, specifically, the presence and

placement of a thesis statement. The second feature was “start-sustain-turn-sum” vs.

“introduction-body-conclusion.” They found that English essays generally place more

emphasis on form, because the introduction of English essays brings out the theme, the

middle contains the argument with its supporting evidence, and the ending summarizes the

essay. The third feature that they studied was circular vs. liner topical development with

respect to topic sentences and topic changes. They found that Asian ESL students delay

introducing the purpose of their writing and can abruptly shift their viewpoint. Their fourth

contrastive rhetoric feature involved metaphorical language which covered making use of

metaphors and proverbs versus straightforward language. They found that Asian ESL

writers use allusion, analogy, and proverbs to show the beauty of their language, and see this

use as important criteria for grading any writing. Their fifth feature involved explicit

discourse markers which are the marks of coherence and unity. They found that academic

essays written by native English speakers use explicit discourse markers to signal direct

relations between sentences and parts of texts, while Asian ESL writers consider that the

beauty of writing lies in delicacy and subtlety, not in its straight-forwardness.

With respect to teaching and learning applications, their experimental results showed

that an e-course group was successful in learning about defined aspects of English rhetoric

in academic writing. In these courses, ESL student performance reached the level of native

8

English speakers. Data analysis also revealed that e-learning resources helped students

compare rhetorical styles across cultures suggesting that making rhetorical differences

explicit can help learners acquire target language rhetorical development.

Coherence in Writing

In Moore’s research on the nature of coherence (1971), he suggested that good

writing requires logically consistent ideas where sentences are clearly and smoothly

connected. This way, the writing is readable and understandable. He also mentioned that

“writing puts the burden of achieving coherence on both native and non-native writers of the

target language, since both have the responsibility to produce coherent discourse to indicate

unobtrusively logical interrelationships of parts to their readers.” However, as Kaplan has

shown, the difficulty of creating coherent texts is even more challenging for second

language learners who come from a different cultural background (Kaplan, 1987).

Tannen (1984) mentioned that L2 writers may feel compelled to go beyond the

boundaries of their native culture’s writing conventions because organizing their ideas into a

unified coherent discourse bears cultural significance. However, coherence in English

writing can be better achieved through certain strategies, such as introductory activities,

explicit teaching, awareness-raising tasks, and writing practice (Lee, 2002).

Topic Structural Analysis

Somlak, et al. (2013) examined two groups of Thai students’ writing. Their data was

collected through a pre-test and the post-test essay writing protocol with two selected essays

from each participant across a subject cohort consisting of high and low proficiency

students.

9

Results indicated that Topical Structural Analysis (TSA) instruction had a

significantly positive effect on students’ writing quality. TSA is a revision strategy taught to

students that raises student “awareness of [the] importance of textual coherence and helps

them clearly understand its concept (Somlak, et al: 2013:60). More specifically, TSA

instruction was found to be more beneficial to low proficiency students than high

proficiency students. Further, they found that both successful and less successful students

employed sequential progression the most in their essays.

In a similar study involving an analysis of a corpus of Philippine student writing,

Yin (2015) found that topical clause sequencing, uncovered by marking initial sentence

elements (ISE), grammar subjects, and topical subjects revealed the relationship not only

between topical structure and the logical presentation of ideas, but also between the

development of extended discourse meaning (Yin, 2015).

These results suggest that Topic Structural Analysis (TSA) can be used to identify

problems in student writing. For this reason, TSA forms one of the analytical instruments

used in this present study. The topical structure analytical approach (TSA), developed by

Lautamatti (1987), analyzes coherence by examining the internal topical structure of each

paragraph as reflected in the repetition of key words and phrases. TSA also considers both

global and local coherence of overall discourse topic.

Lautamatti (1978) investigated the relationship between sentences in a text and

discourse topic. Sentence topics, which are units of meaning organized hierarchically in the

text, make a semantic contribution to the development of the discourse topic.

She states that:

"The development of the discourse topic within an extensive piece of discourse may

be thought of in terms of a succession of hierarchically ordered subtopics, each of which

10

contributes to the discourse topic, and is treated as a sequence of ideas, expressed in the

written language as sentences. We know little about restrictions concerning the relationship

between sentences and subtopics, but it seems likely that most sentences relating to the same

subtopic form a sequence. The way the written sentences in discourse relate to the discourse

topic is ... called topical development of discourse." Lautamatti (1978: 71)

The discourse topic is the central idea of a stretch of connected discourse. The topic

is what the discourse is about as a whole paragraph. In order to develop the discourse topic,

sub-topics are treated as a sequence of ideas, which contributes to the discourse topic.

11

Chapter 3: Features of Korean Language, Culture, and Academic Writing

Given the strong relationship between language and culture (Wierzbicka, 1985;

Goddard, 1992; D’Andrade, 2001) as well as the previously discussed relationship between

culture and rhetorical development, it is now necessary to discuss some of the relevant

linguistic features of Korean and English. This chapter presents similarities and differences

between Korean and English in terms of origin, typology, phonology, syntax, and so forth.

Linguistically, there are huge differences between English and Korean. English is an

Indo-European language, while Korean is often placed in the Altaic language family

2

.

Typologically, Korean is an agglutinative language

3

, whereas English an analytic language.

Although not related to writing, phonologically English is a stress-timed language, but

Korean is a syllable-timed language which means individual word stress is insignificant.

English is primarily a right-branching SVO language, but Korean is primarily a left-

branching SOV language. These different linguistic features hinder Korean Freshmen’

attempts to write English essays. The Integrated Korean textbook (2010: 13) explains how

learning Korean is extremely difficult for native English speakers:

Korean is one of the most difficult languages for native English speakers to learn

because of the vast differences between English and these languages in vocabulary,

pronunciation, grammar, and writing system, as well as in the underlying tradition,

culture, and society. English speakers require three times as much time to learn this

“difficult language” as to learn an “easy language,” such as French or Spanish, to

attain a comparable level of proficiency.

2

It is a language whose classification is in dispute. Some linguists believe it exists in a family of its own;

others place it in the Altaic language family and claim that it is related to Japanese.

3

Verb information such as tense, mood and the social relation between speaker and listener is added

successively to the end of the verb.

12

Many Koreans believe it is also as hard for Korean native speakers to acquire English

(Kim, 2012). Additional distinctive and salient differences are discussed below including

word order and a situation-oriented focus which means that, for Korean speakers, it is

possible to omit important elements in an argument.

Related grammatical features of the Korean language

Word order

The most obvious distinctive feature between English and Korean is word order.

Declarative sentence word order in English is SVO, whereas in Korean it is SOV (Subject +

Object + Verb), where the information-heavy verb comes at the end of the sentence or

utterance. Listeners or readers of Korean need to pay attention until the speakers or writers

finish their sentences. However, sometimes Korean is called a “free-word order” language

because the elements can be scrambled for emphasis or other figurative purposes, as long as

the verb or adjective retains the final position (Greenberg, 1963; Seong et al, 2008; Korean

grammar dictionary, 2010:8). All other elements, such as the subject and the object, appear

before the verb or adjective. Integrated Korean further explains:

In the English sentence “John plays tennis with Mary at school”, for example,

“John” is the subject because it appears before the verb and denotes an entity which

the rest of the sentence is about. “Tennis” is its object because it appears

immediately after the verb and denotes an entity that directly receives the action of

the verb. The other elements (“with,” “Mary” and “at school”) follow the object. The

Korean word order would be “John school-at Mary-with tennis plays”. Notice here

that while English prepositions always occur after the element they associate with, as

in “at school” and “with Mary,” Korean particles are all postpositions.

(Integrated Korean, 2010, p.4)

Also, Korean is a pre-modifier language (left-branching language) and head final

language, whereas English is generally a post-modifier language (right-branching language)

and head initial language. In the Korean language, modifiers always appear in front of a

13

noun. Those features are important grammatical elements used to express a Korean writer’s

intention or information indirectly to readers while not imposing on the reader. Since the

head follows its complements (modifiers), messages (heads) are delayed. In other words,

core data is delivered indirectly, so readers are required to predict the message. These

features make it easy to express abstract or vague concepts between interlocutors by using

the Tact Maxim

4

which can impose less on the other party (Lakoff, 1973; Leech, 1983).

The last distinctive feature of Korean language I wish to discuss is the discourse

ordering concept. Although Korean rhetoric is “mostly inductive” and “specific-to-general”

(Jung 2006), when ordering hierarchical concepts in discourse, Korean speakers generally

progress from the large and whole concept to the smaller and more detailed concept.

For example,

Larger concept Smaller concept

A Korean address is:

Nation, State, City, Street address or P.O. box number

South Korea, Seoul, gang-nam gu, gang-nam dong 1987

Many scholars suggest that English rhetoric is “mostly deductive” and “general-to-

specific” (Jung 2006). English speakers generally place the detailed concept first and

develop their logic toward the larger concept.

4

One of the politeness theory elements (Leech, 1983): Sympathy Maxim, and Agreement Maxim.

14

Smaller concept Larger concept

An English address is:

Street address or P.O. box number, City or town, State, Nation

1987 N 650 W, Provo, Utah, U.S.

Son (2001) provides further examples of these discourse ordering differences between

Korean language speakers and American English speakers that are summarized below.

Conversation between Korean and American (Son, 2001)

American: Where are you calling from?

Korean: Downtown.

American: Where is downtown? Bigger concept

Korean: Myungdong.

American: Where is Myungdong?

Korean: Near the post office.

American: Are you calling from a telephone booth?

Korean: No, I’m calling from a coffee shop.

American: What coffee shop? Smaller concept

Korean: The Rose Coffee Shop.

Conversation between Americans (Son, 2001)

American1: Where are you calling from?

American2: From the Rose Coffee Shop, near the post office in Myungdong.

American1: Where’s Myungdong?

American2: It’s downtown, near the Lotte Department Store.

Smaller concept

Bigger concept

As can be seen, in general Korean discourse ordering style follows larger to smaller concept,

but American ordering style follows smaller to larger concept. As will be discussed below, this

difference in discourse ordering impacts the development of topic in student essays.

15

Omitting grammatical elements

The Korean language is a context dependent language, meaning its discourse is

oriented toward its context (Jang, 1994). Since verbs reflect the interlocutors’ relationship

and contain situational information, important informational elements do not have to be

repeated. In the Korean language, verbs are more important than subjects. Consequently,

discourse topics can be omitted if they are redundant as determined by the preceding

context. In Korean, subjects/topics are often omitted when they are obvious. Omissions are

not limited to subjects, but also include any element that can be omitted as long as the

context makes the referent clear.

For example,

“How are you?” “안녕하세요(Annyeonghaseyo)?” means “How are?”

There is no subject.

Another example,

“Thank you.” “고맙습니다 (Gomapseupnida)” means “Thank.”

There is no subject as well.

Inserting the pronoun ‘you’ or ‘I’ in the above Korean expressions would sound

awkward in a normal context, unless ‘you’ or ‘I’ is emphasized or contrasted with someone

else. On the other hand, Academic English requires explicit reference in order to avoid

ambiguity (Halliday and Hasan, 1976) and create a sense of exactness and scientific

credibility. As will be seen below, Korean writers writing in English may omit discourse

topics, relationships, or conclusions that they view as being obvious based upon the context

or previously supplied information within a reader-responsible stance. Native English

readers, however, require more of that information so they can make sure that they totally

understand the writer’s intent within a writer-responsible stance.

16

Miscellaneous

The most common grammatical mistakes by Koreans in writing English essays are

misuse of tenses, definite and indefinite articles, prepositions, and pronouns. (Seong et al,

2008). Some of these errors are caused by differences between Korean and English. Korean

has three tenses: past, present, and future; while English only has two tenses: present and

past, with several other verb aspects. However, future and Korean tense usage is different

than English (Cho, 2003).

“Even though the tense/aspect systems of two languages show some similarities in

their basic meanings of the tense/aspect formatives, many differences can be found

in expressing their specific or contextual meanings. In English, the meanings of the

tense/aspect formatives have quite systematic correspondence among them, because

temporal meaning is expressed by means of strict formal, grammatical opposition of

verbs. On the other hand, Korean language depends on adverbial expressions or

contexts for its temporal meaning, as well as on the formal, grammatical opposition

of verbs. That is, the various specific, contextual meanings of the tense/aspect

formatives in Korean are mostly caused by its formative-neutralization tendency.

Therefore, the differences in tense/aspect systems of English and Korean seem to be

explained as typological differences between the languages in which tense/aspectual

meanings mainly depend on grammatical devices, and the languages in which

tense/aspectual meanings depend on lexical devices as well as grammatical devices.”

For example,

Korean way of speaking

English way of speaking

나는 지금 노래를 부른다.

(Naneun jigeum noraereul bureunda)

Grammatically correct

I sing a song now.

Grammatically incorrect

나는 지금 노래를 부르고 있다

(Naneun jigeum noraereul bureugo itda)

Grammatically correct

I am singing a song now.

Grammatically correct

The use of articles is also very limited in Korean. Instead of articles, using

demonstrative pronouns is common. Personal pronouns are not used much in normal

contexts. Instead of using a personal pronoun, Koreans use a title for addressing or referring

17

to other people. They especially do not use “he” or “she” when referring to the elderly. In

addition, Korean has post-positions, because it is an agglutinative language, and the usage of

postpositions is quite different from English preposition use.

For example,

나는 방에서 친구와 밥을 먹었다.

(Naneun baneseo chinguwa babeul meogeotda.)

I was eating rice at the kitchen with my friend.

The above description of different grammatical and discourse features of Korean and

English shows the potential sources of first language interference problems in English

academic writing for Korean Freshmen. The actual nature of some of this interference will

be discussed in detail in the results and analysis section of this thesis.

Cultural differences

As has been noted, cultural differences play a large part in how ideas are presented

in discourse. It is commonly understood that the underlying nature of Korean society can be

encompassed by referencing three key words: collectivism (harmonious), politeness

(indirectness), and face (reputation). Those features can also affect Korean Freshmen’

English writing style with respect to a reader-responsible orientation, and an inductive

writing style that creates, from an English reader’s perspective, a weak development of the

author’s arguments.

Collectivism or harmonious culture in Korean culture

As noted previously, traditional Korean culture is oriented toward collectivism

5

.

5

5

Culture’s Consequences: (Individualism vs. Collectivism) “The degree to which individuals are integrated

into groups.” This dimension has no political connotation and refers to the group rather than the individual.

Cultures that are individualistic place importance on attaining personal goals. In collectivist societies, the

goals of the group and its wellbeing are valued over those of the individual. (Hofsted, 1980)

18

Collectivism tends to create vertical hierarchy along with an emphasis on horizontal

harmonious relationships (Hofstede, 1980). Historically, within socio-political contexts,

Korea maintained a relatively harmonious hierarchical bureaucratic system from the

Gojoseon Dynasty to the Joseon Dynasty era, a period of about 5000 years. In contrast to

Japan and many other civilizations, Korea never experienced a feudal system where social

stability was based on land ownership with the higher classes protecting the lower classes in

return for portions of their crops or services. Instead, a strict caste system existed where the

land-owning free citizens were protected by a strong centralized bureaucratic system (Seth,

2006).

The Korean bureaucratic system depended on a perpendicular relationship. This

means that, in order to become a government official under the King, and thus ensure social

success, people had to take a civil service examination. So, in the bureaucratic system,

social status was emphasized, and was intertwined with educational achievement. This

structure remains to the present day (Hong, 1992).

Korean society’s basic unit is the family. Family is important in traditional Korean

culture because Korean’s traditionally lived within a clan society where everyone was

related by blood (Choi, 1996). Members in their family are tied to each other, so a family

members’ behavior can reflect on the rest of their family. It is important for them to behave

themselves with discretion, not to humiliate other family members, or the clan society they

belong to. In other words, keeping other members’ face is the one of the crucial elements in

a harmony-emphasized society (Kim, 2013; Choi, 1996).

In this system, one must show respect to their parents, seniors in their village, people

who have higher social standing, and their king. Such a sophisticated society system created

19

a pattern of circumlocutions, verbosity, innuendo, equivocation, or euphemisms as a

politeness strategy when communicating with each other. Those strategies leave room for

interpretations that avoid conflicts and show their respect to the counterpart. The example

below provides a simple and common way of showing politeness by using deference

vocabulary at the grammatical level.

For example,

친구에게 말할 때: 아침밥 먹자.

(achimbab meogja)

Addressing friends: Let’s eat breakfast. (Omit subject)

할아버지께 말씀드릴 때: 할아버지! 아침 진지 잡수세요.

(Harabeoji! Achim jinji japsuseyo.)

Addressing a Grandfather (elder person): Grandfather! Have a breakfast, please.

(Speak the title of “grandfather”)

As Hall (1976) mentions, Korea is a highly context-based society. Language is used

in a collectivism society to enhance social structure either positively with politeness

strategies, or negatively with shaming strategies, all in an effort to preserve others’ face.

This means that Koreans are reluctant to be overly assertive in presenting or defending an

individualistic or creative idea or proposition. This stance is in contrast to more

individualistic Western notions of creative independence and speaking or writing with one’s

own “voice” (Wierzbicka, 1985). As will be seen in the Results and Analysis section of this

thesis, these stance differences create difficulties for Koreans writing in English within

Western Academic genres.

Face, Politeness in Korean culture

As noted, emphasis on face and politeness is a result of the collectivist social system

and society. Someone who has a higher sensitivity to face also has a higher desire to protect

20

or keep others’ face by avoiding conflict and by maintaining amicable relationships (Kim,

2009).

Lakoff (1990) builds upon Grice’s (1975) Cooperative Principle and sees politeness

as ‘a system of interpersonal relations designed to facilitate interaction by minimizing any

inherent conflict or confrontation (Lakoff, 1990:34).” Consequently, it may be that a writer

from a collectivist society is less likely to be assertive and direct than a writer from an

individualist society. In addition, Brown and Levinson (1987: 5) consider politeness as a

strategy to avoid conflict or minimize any face threats. Thus, in a Korean context, polite

face-saving writers are going to be less assertive, and express their ideas more indirectly.

As will be explained below, the dominant Korean ethnic values of collectivism,

indirectness, and face are distinctive features that contribute to a reader-responsible

orientation and inductive rhetorical reasoning.

Inductive way of reasoning Vs. Deductive way of reasoning

In order to further understand the differences between reader responsibility (a

preferred Korean pattern) and writer responsibility (a preferred English pattern), it is

important to first understand inductive and deductive ways of thinking and their connection

to cultural backgrounds and philosophies. The deductive approach versus the inductive

approach can be seen in terms of pursuing scientific logic versus pursuing philosophical

logic.

Deductive reasoning starts with a general statement and examines the possibilities to

reach a specific and logical conclusion following Aristotle’s notion referred to as a

syllogism. This idea implies that there is a generic rule which can be applied to everything

by transcending space and time. Based on this fundamental principle and theory, a deductive

21

writing style draws a conclusion. The English-based academic writing style in most fields

usually follows this approach because it emphasizes conceptual and logical comprehension

through deduction of facts. So, a writer needs to persuade a reader with a coherent

movement toward a reasonable interpretation of the logic. Thus, it becomes the writer’s

responsibility to persuade the reader.

On the other hand, as Xing, M., et al, (2008) explain, Asian-based inductive

reasoning is based on shared knowledge with a shared context or set of shared examples that

indirectly lead to the development of an understanding, result, or conclusion. This approach

suggests that there are various methods or pathways to find answers to problems. A concept

is interpreted within a context shared by the writer and reader. Inductive reasoning shows

how the rule or concept works. That means that the major point of view of a piece of writing

derives from the “experiencer” or reader of the text, not the writer. For example, in his book

Unchangeable

6

(Chapter 20), Confucius says that knowledge is accomplished through doing

what is to be learned. Without individual experience, one cannot know that they know

knowledge. So, in Confucian-influenced Asian culture, knowledge (theory) and experience

(practice) are not separated.

Experiential conceptual understanding is embedded in Asian culture, and the

interaction between reader and a writer is central. This is in contrast to a Western approach

where the writer unilaterally leads or persuades a reader. Since the Korean persuasion

process depends on a reader’s own experiences, a reader’s role is interpreting the writer’s

intention, understanding ambiguity, and independently inferring abstract ideas. Knowledge

6

Chung yung 中庸 which means "Centre," or "Unchangeable" is one of four Confucian texts. When published

together in 1190 by Chu Hsi, a great Neo-Confucian philosopher, they became the famous Ssu shu ("Four

Books").

22

is gained through analysis and observation of phenomenon, as well as looking deep inside of

ourselves or deeply inside others. When a reader “reads between the lines” in a text, the

reader and the writer develop a special connection.

For this reason, reader subjectivity through inferring abstract ideas from the writer’s

text is not seen as an obstacle to understanding within a reader responsibility writing

context. This concept is a common idea in Asian cultures (Xing, M., et al, 2008).

Academic writing

According to Biber (2010), the definition of academic writing in English refers to a

particular style which has elaborated structures with complex grammar and with explicit

meaning relations. This feature is the opposite of spoken registers. In his research, he finds

that academic writing and spoken registers, especially conversation, have dramatically

different linguistic characteristics.

…academic writing is structurally 'compressed', with phrasal (non-clausal)

modifiers embedded in noun phrases. Additionally, we challenge the stereotype

that academic writing is explicit in meaning. Rather, we argue that the

'compressed' discourse style of academic writing is much less explicit in

meaning than alternative styles employing elaborated structures. These styles

are efficient for expert readers, who can quickly extract large amounts of

information from relatively short, condensed texts. However, they pose

difficulties for novice readers, who must learn to infer unspecified meaning

relations among grammatical constituents (Biber, 2010).

Mastery of the complex academic code is difficult for students at both secondary and

tertiary levels. Catherine Snow’s research (1991) suggests that to achieve academic success

requires improving the ability to comprehend and produce decontextualized language by

exposing students to large quantities of explanatory theme-based reading in addition to

narrative reading. She shows that academic writing is different from narrative writing found

in diaries or e-mails used in daily lives. Cummins (1979) labels this type of narrative writing

23

“Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills” (BICS) and academic writing as “Cognitive

Academic Language Proficiency” (CALP). BICS-based conversational fluency is required

to act at a functional level to interact socially with other people in social day-to-day

situations.

CALP refers to formal academic learning. Academic language acquisition not only

means the understanding of vocabulary in content areas, but also the acquisition of the

ability to compare, classify, synthesize, evaluate, and infer using appropriate academic

language. The distinction between BICS and CALP has contributed to an understanding of

language proficiency and its relationship to academic achievement. That means, students

regardless of their language, need to be educated in CALP by practicing academic writing.

24

Chapter 4: Methodology

Having reviewed relevant research literature including the nature of academic

English, and differences between Korean and Western cultural preferences with regards to

writing, I will now discuss the research methodology.

Research questions:

As noted earlier, the research questions for this study are:

1) What if any, are the differences between Korean Freshmen writing and

American Freshmen writing?

2) If there are differences, what are the major rhetorical development problems

that Korean ESL students face in freshman composition classes?”

3) If American Freshmen write in a linear way, is it natural or is the linear

“logical” frame a learned feature of academic writing in western culture?

4) Do American Freshmen write in a deductive style, while Koreans write in an

inductive style?

In order to answer the research questions, the following procedural steps were taken.

First, I constructed a corpus of international Freshman Composition Korean student writing

and a corpus of Freshman Composition American student writing. Second, I conducted

discourse analyses on these corpora using the TSA method while adding identification

markers for TS (Topic Sentence), and TH (Thesis Statement), and IR (Irrelevant

Information). Third, I analyzed the corpora using ISE (an Initial Sentence Element), GS

(Grammatical Subject), and TS (Topical Subject) according to Lautamatti’s five types of

25

ISE, GS, and TS

7

categories. Forth, I examined the corpora using a modification of

Lautamatti’s three types of thematic progression that allow for the identification of topic

development using: (1) PP (parallel progression), (2) EPP (extended parallel progression),

(3) SP (sequential progression) (4) ESP (extended sequential progression), and (5) IR

(Irrelevant Information such as transition or listing new topic). Lastly, after analyzing the

essays, I sorted their grammatical error types according grammar rules in order to discover

differences in error types between American and Korean Freshmen essays.

Subjects

Applying these discourse analytical strategies provides insights into the

organizational patterns favored by 25 international Korean Freshmen and 25 American

Freshmen. Consequently, 50 students’ Rhetorical Analysis

8

writing samples were taken

from Korean Freshmen and American Freshmen in their freshman composition classes at

Brigham Young University (Utah, U.S.A.).

I chose writing samples from BYU freshmen composition classes because students

in these classes have been admitted to BYU so they have met minimal standards for BYU

entrance which are very high compared to most other universities. They satisfied the

7

Lautamatti (1987) proposes five types of the co-occurrence of ISE (an initial sentence element), Grammatical

Subject and Topical Subject: Type 1 occurs when all the three elements coincide. Type 2 occurs when the ISE

is separate from the mood subject and the topical subject, in which the latter two coincide. Type 3 occurs when

the ISE coincides with the mood subject, but the topical subject is separate. Type 4 occurs when the ISE

coincides with the topical subject but the mood structure is separate. And Type 5 occurs when all three

elements are separate. Lautamatti provides the simplified presentation of the five types as mentioned in

Chapter 2.

8

Rhetoric is the art of effective or persuasive speaking or writing, especially the exploitation of figures of

speech and other compositional techniques. the study of how writers use words to influence readers. (Oxford

dictionary) A rhetorical analysis requires writers to apply their critical writing skills to break a text in their

essay. They use a rhetorical analysis to articulate how the author writes, and to create a certain effect such as

persuasion or inform. UBC Writing Centre. 7 May 2007. The University of British Columbia. 10 December

2007. http://www.writingcentre.ubc.ca/workshop/tools/rhet1.htm

26

standard for getting into university so they are ready to begin academic study. Even though,

I did not consider students’ personal backgrounds with respect to their prior-to-BYU-

admittance writing ability and instruction in writing, I am confident that they had reached

certain minimal standards due to their BYU admittance.

The reasons why I chose the students’ rhetorical analysis essays and draft are:

1. Using the rhetorical analysis, it is easy to evaluate elements of writers’ purpose

and the development ideas

2. Using the rhetorical analysis, it is easy to discover the writer’s style, such as a

deductive approach to writing or an inductive approach, because writers make many

strategic decisions when attempting to persuade their readers

3. In this study, students’ first draft essays, without teacher feedback, were used

because there is a possibility of teachers’ feedback influence in their final essays. So if we

used later drafts it would be hard to know the original rhetoric used by the writers.

Three Paragraphs

A total of 150 paragraphs were analyzed in this study. Three paragraphs of longer

essays were analyzed in each Korean and American Freshmen’ writing. According to the

Oxford Dictionary definition, a “paragraph” means “A distinct section of a piece of writing,

usually dealing with a single theme and indicated by a new line, indentation, or numbering.”

However, since this study analyzed drafts of novice freshmen’s essays, the length of

the essays and paragraphs displayed huge differences. In addition, writers did not divide

their ideas into clearly defined paragraphs. Some of the students wrote one whole page as a

single paragraph, while other students only wrote two short sentences.

27

So, for the purposes of this research, paragraphs were designated based upon how

the students had decided what a visual paragraph was. According to this definition, I chose

three paragraphs from each student writing sample.

I chose not to focus on each student’s complete essay because the writing samples

were not the final essays in their assignment. Many students had not finished their essays

when they turned in these paragraphs. Thus, I concluded that analyzing three paragraphs

was sufficient to determine the presence or absence of each writers’ logic or rhetorical

development.

Reliability and Validity

Lautamatti’s (1987) TSA method is widely used in peer reviewed published

literature and, as noted in Chapter 2, many peer-reviewed, published studies have used this

method. Thus it is a valid research method. Also, when I analyzed students’ essays, I set up

coding criteria and checked my coding with a professional writer, an experienced ESL

teacher, and other professors thus increasing rater reliability.

Lautamatti’s types of sentence

Lautamatti (1987) describes three basic concepts used in the TSA method: (1) the

initial sentence element (ISE), (2) the mood/Grammatical Subject (GS), and (3) the Topical

Subject (TS). The ISE is the first element in the sentence. It is the first indicator of what the

sentence is about, but often it is not the topic of the sentence. The mood subject is the

Grammatical Subject (GS) and will hereafter be referred to as the grammatical subject. This

element is usually, but not always, what the sentence is about. So, readers expect this to be

the main idea of the sentence. Lastly, the Topical Subject (TS) is what the sentence is

28

actually about. Sometimes the topical subject is not in initial or grammatical subject

position.

Lautamatti (1987) proposes five types of the co-occurrence of ISE, Grammatical

Subject and Topical Subject: Type 1 occurs when all the three elements coincide. Type 2

occurs when the ISE is separate from the mood subject and the topical subject, in which the

latter two coincide. Type 3 occurs when the ISE coincides with the mood subject, but the

topical subject is separate. Type 4 occurs when the ISE coincides with the topical subject

but the mood structure is separate. And Type 5 occurs when all three elements are separate.

Lautamatti provides the simplified presentation of the five types as follows:

Type 1: ISE = topical subject = mood subject

Type 2: ISE ≠ topical subject = mood subject

Type 3: ISE = mood subject ≠topical subject

Type 4: ISE = topical subject ≠ mood subject

Type 5: ISE ≠ topical subject ≠mood subject

For clarity, examples taken from the corpus of Yin’s study (2015) of each type are

offered below (where the ISE is italicized, the grammatical subject is underlined, and the

topical subject is bold-faced):

Type 1 example: Outdoor games offer a lot of health benefits and also the

opportunity to have social interaction and new connections with the people of the

same sport. (H9)

Type 2 example: However, indoor games are very limited in terms of advantages

compared to outdoor games. (H9)

Type 3 example: There are different kinds of dresses that a woman may wear. (L8)

Type 4 example: Although college life has been hell-like, there you can experience

almost everything you haven’t experienced in high school. (L9) (Type 4)

Type 5 example: Because of this, it is a lot easier to screw up lead guitar. (H15)

(Yin, 2015)

Lautamatti’s TSA and Simpson’s ESP

29

I also analyzed the corpora according to Lautamatti’s three types of thematic

progression that allow the topical structure analytical approach (TSA) to track how the topic

is developed. She suggests three types of thematic progression that allow the TSA to track

how the topic is developed: (1) parallel progression (PP), (2) extended parallel progression

(EPP), and (3) sequential progression (SP).

Parallel progression (PP) occurs when two consecutive clauses contain the same

topical subject in the same sentence position. These clauses, consisting of the same topical

subjects placed one after the other, develop the topic along parallel lines. This method of

topical development is expected by native English readers and helps them follow the logic

of the text.

Extended parallel progression (EPP) occurs when a topical subject is repeated in two

clauses that are not consecutive. These clauses, with the same topical subject, but separated

by other sentences or clauses, enable readers to link back to the first parallel clause or

sentence, thus enhancing textual cohesion and coherence.

Sequential progression (SP) occurs when the rheme element of a clause becomes the

theme element of the consecutive clause. Clauses that take the rheme element and make it

into the following theme element follow a form of topical development expected by readers,

thus adding to the readability of the text.

According to Lautamatti's notion, topical depth is the relationship between the

progression of sentence topics and the semantic hierarchy of a text. The sentence topic

stated at first in an extended sentence indicates the highest level in the semantic hierarchy. It

is the discourse topic. The sequence of sentences showing a discourse topic by developing a

30

succession of sentence topics is called topical progressions. Topical progression helps

individual sentences cohere logically. These notions are summarized in Figure 4.1 below:

Connor (1996) explains a system of three distinct progressions

9

by mapping: parallel

progression: (a,b), (a,c), (a,d), extended parallel progression: (a,b), (b,c), (a,d), sequential

progression: (a,b), (b,c), (c,d).

Simpson (2000) introduced extended sequential progression (ESP) which can be

defined as the rheme

10

element of a clause being taken up as the theme of a non-consecutive

clause. That is, a new rheme is revealed for the first time in an initial sentence, but not as the

topical subject. This rheme is then repeated as the topical subject, or, in this case, theme of a

subsequent clause. However, a number of clauses intervene between the first rheme and the

following theme.

9

Parallel progression, in which topics of successive sentences are the same, producing a repetition of topic that

reinforces the idea for the reader; • sequential progression, in which topics of successive sentences are always

different, as the comment of one sentence becomes, or is used to derive, the topic of the next; and • extended

parallel progression, in which the first and the last topics of a piece of text are the same but are interrupted

with some sequential progression. (Hoenishc, 2009)

10

Rheme is the remainder of the message in a clause which theme is developed. Theme is the given

information serving as the point of departure of a message (Halliday, 2004).

31

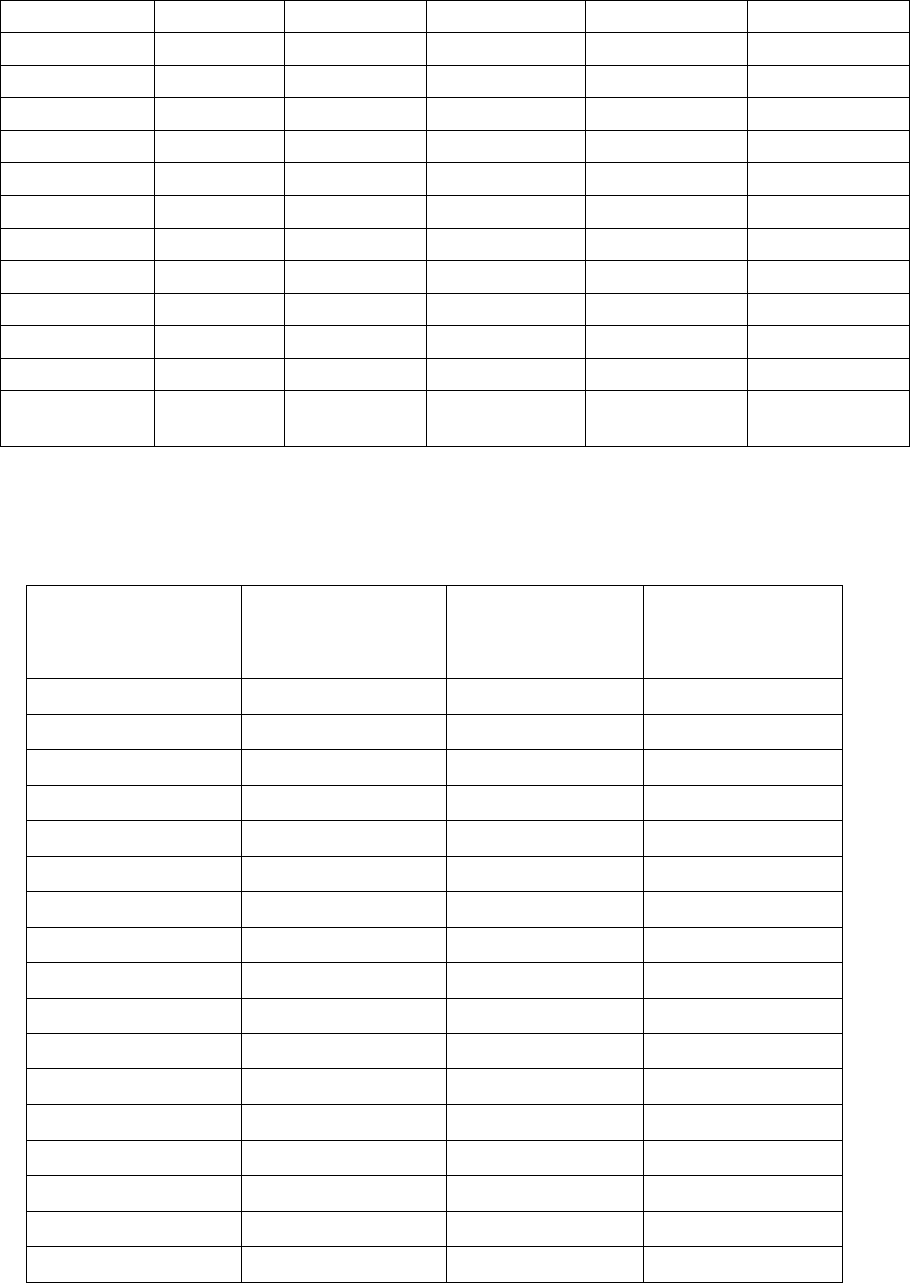

Figure 4.1

Summary of the Topic Structure Analytical Approach

The Topical Structure Analytical Approach (TSA)

Three basic concepts used in the TSA method:

(1) the initial sentence element (ISE)

(2) the mood/grammatical subject (GS)

(3) the topical subject (TS)

Three types of thematic progression that allow the TSA to track how the topic is developed:

(1) parallel progression (PP): occurs when two consecutive clauses contain the same

topical subject in the same sentence position.

(2) extended parallel progression (EPP): occurs when a topical subject is repeated in two

clauses that are not consecutive. These clauses, with the same topical subject, but separated

by other sentences or clauses, enable readers to link back to the first parallel clause or

sentence, thus enhancing textual cohesion and coherence.

(3) sequential progression (SP): occurs when the rheme element of a clause becomes the

theme element of the consecutive clause.

(4) extended sequential progression (ESP) which can be defined as the rheme element of a

clause being taken up as the theme of a non-consecutive clause. That is, a new rheme is

revealed for the first time in an initial sentence, but not as the topical subject. This rheme is

then repeated as the topical subject, or, in this case, theme of a subsequent clause. However,

a number of clauses intervene between the first rheme and the following theme. In my

analysis, the absence of these rhetorical development devices is indicated as either “no

progression” of topic, or, in some cases, “irrelevant information.” (Simpson, 2000)

As noted, it has been shown that uncovering these rhetorical strategies are keys in

understanding how a writer develops a topic in a paragraph, and how a reader follows the

development of that topic (Lautamatti, 1987; Simpson 2000). This present study is based on

the notion that applying an analytical method that uncovers these elements will help identify

areas in paragraphs where novice writers may not have developed their topic to meet the

expectations of native English readers.

32

In addition to Lautamatti’s criteria and Simpson’, my analytical method also marked

common rhetorical errors including Irrelevant Information (IR)

11

and repetitive or redundant

information as categories that may contribute to problems in rhetorical development. In my

analysis, Irrelevant Information (IR) is defined as the absence of these rhetorical

development devices as well as the transition or listing of a new topic which does not add to

or develop the main topic.

The absence of cohesive rhetorical development devices is indicated as “Irrelevant

information” (IR) a new category developed for this research. IR is information provided by

the writer that is extraneous to the topic. IR is also information provided by the writer that is

a distraction from the topic under development. This type of information hinders the reader

from understanding the writers’ intent. Redundant information which is included in the

Irrelevant Information category is information provided by the writer that has already been

provided. Repetitive or redundant information is a distraction from the topic under

development. This type of information also hinders the reader from understanding the

writers’ intent. The IR category also involves new topic or new information which does not

belong to the PP, EPP, SP, or ESP.

The Topical Structure Analytical Approach (TSA) method, with Topic Sentence

(TS), and Thesis Statement (TH), criteria as mentioned above were used to analyze the

rhetorical development of these essays. Because both Korean and American students were

writing unedited first drafts with so many rhetorical and grammatical weaknesses, doing a

11

If there is absence of the rhetorical development devices, it is regarded as IR (Irrelevant

information) which can include “Transition or Listing new topic” which leads to no progression of the topic. In

other words, Irrelevant Information (IR) is not a clear topic statement (TS), but it is possible for it to be a

“Topical Subject.”

33

narrow analysis would not develop meaningful results. For this reason, I used four analytical

approaches: The Topical Structure Analytical Approach (TSA), Topic Sentences (TS),

Thesis Statements (TH), and an analysis of grammar errors. Also, I wanted to do a cross-

cultural analysis so I felt that focusing on thesis statements and topic sentences allowed this

research objective to be achieved.

Topic Sentences and Thesis Statements

In my analysis, in order to distinguish between inductive style and deductive style in

Freshmen’s essays, I coded for Topic Sentences (TS) and Thesis Statements (TH) (Condit

and Koistinen, 1989, Tomlin, 1985, Van Dijk, 1980, and Grimes, 1989). In standard

academic writing, native English readers expect one topic sentence at the beginning of each

paragraph. The Thesis Statement (TH) is a sentence that tells the reader what the writer

believes, and what the writer is trying to convince the reader to believe in.

Consequently, identifying the location of the topic sentence is a way to discover the

possible inductive versus deductive style used by the writer. Experienced academic readers

would expect each of the introductory paragraphs to contain a thesis statement as well as a

topic sentence, with the topic sentence located near the beginning of the paragraph.

Deductive versus inductive problem

Deciding on deductive versus inductive development is difficult especially for first

draft unedited student writing. For the purpose of this present analysis, I have labeled

deductive and inductive development based upon the location of the thesis statement in a

paragraph. The reason why I distinguished between inductive style and deductive style, is

because there is a relationship between linear and spiral/circular development and

deductive/ inductive development. I interpreted Kaplan’s “linear” style as deductive and the

34

non-linear style as inductive. According to Hinds (1987), Korean writers’ reader-responsible

writing style presents English native readers with more inferential work to do such as

decoding ambiguity, abstract ideas, and imprecise information. Such traditional Korean

writing style and rhetoric patterns can be interpreted by native English readers as a non-

linear style which uses more topic subjects because of this indirect “beating the bushes”

approach.

I will now present the results of this analysis in the following chapter.

35

Chapter 5: Results and Analysis

In this chapter, I describe how 50 essays written by Korean and American Freshman

composition class students with the same topic assignment were analyzed within a

qualitative research framework, using the criteria mentioned above. Results are indicated in

the tables below.

Surprisingly, the results of this study showed that overall Korean Freshmen used a

more linear deductive style of writing with fewer grammatical errors than the American

Freshmen did, even though the American Freshmen writers wrote more sentences and their

sentences were longer. American Freshmen used more non-linear, spoken rhetorical patterns

rather than a linear academic writing style. Korean Freshmen used a higher number of linear

deductive writing features. Overall findings suggest that instruction in the academic writing

style is more important than possible culturally influenced rhetorical patterns.

The results for the 25 American Freshmen also show it is necessary to be trained to

write in a linear style of writing. This is because an academic writing rhetorical pattern is

different from ordinary personal writing (letters, texts, emails, journal entries) and different

from literary genres such as poems or novels.

This suggests that the so-called circular style is not inherently Asian, and neither is

the Western linear pattern inherent in American writers. It may be that apparent differences

have more to do with instruction and the pragmatic intent of writers from both cultures.

English readers expect a clear thesis statement in an expository text. However,

Korean writers may not wish to assert their beliefs so noticeably in a way that, for Koreans,

may suggest arrogance. Thus, Korean writers may hide their thesis statement within a

36

suggestive discourse strategy (Eggington, 1987). Consequently, the presence or absence of a

clear TH is a way to measure if a paragraph conveys clear meanings.

Identifying Topic Sentence and Thesis Statements

The analysis begins with Table 5.1 (look at page 36), which shows the position of

the Topic Sentence (TS)

12

and the Thesis Statement (TH)

13

in Korean and American

Freshmen’s writing in their paragraphs. The position of a Topic Sentence and a Thesis

Statement can be an indicator of inductive or deductive development. Most traditional

Korean style of writing is inductive, but, as Table 5.1 shows, many Korean Freshmen used

an inductive writing style. Also, many students wrote the topic sentence and thesis statement

in the middle of the paragraph. So it is unclear if this approach is inductive or deductive.

Also, there were nine more examples of Korean Freshmen who did not write topic sentences

and five more examples of Korean Freshmen who did not write thesis statements than

American Freshmen’ paragraphs.

As mentioned previously, within an ideal academic writing style, a topic sentence

offers the main idea of the paragraph, and thus every paragraph should include it. This is

because a topic sentence indicates the writer’ intention for the paragraph. Generally, the

topic sentence appears at the beginning of the paragraph especially in academic essays. A

thesis statement contains a concise summary of the main point, or claim, of the essay. A

12