Walden University Walden University

ScholarWorks ScholarWorks

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Collection

2023

Relationship Between Opportunity for Advancement, Salary/Pay, Relationship Between Opportunity for Advancement, Salary/Pay,

and Retail Salesperson Turnover Intentions and Retail Salesperson Turnover Intentions

Edith Mae Thompson

Walden University

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations

Part of the Business Commons

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an

authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Walden University

College of Management and Technology

This is to certify that the doctoral study by

Edith M. Thompson

has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects,

and that any and all revisions required by

the review committee have been made.

Review Committee

Dr. Laura Thompson, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration

Faculty

Dr. Irene Williams, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Dr. Brenda Jack, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Chief Academic Officer and Provost

Sue Subocz, Ph.D.

Walden University

2023

Abstract

Relationship Between Opportunity for Advancement, Salary/Pay, and Retail Salesperson

Turnover Intentions

by

Edith M. Thompson

MHRM, Walden University, 2018

BBA, Austin Peay State University, 2016

Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Business Administration

Walden University

March 2023

Abstract

Employee turnover intention is the principal antecedent and predictor of employee

turnover behavior, which is a substantial threat to automotive retail dealerships’ current

and future organizational performance. Understanding employee turnover intentions is

vital for dealership general managers to reduce salesperson turnover, manage dealership

costs, and maintain dealership competitive advantages. Grounded in Herzberg’s two-

factor theory, this quantitative correlational study examined the relationship between

opportunity for advancement, salary/pay, and employee turnover intention among

automobile salespeople. Using an online survey administered by Survey Monkey, data

were collected from 76 retail salespeople in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Alabama. The

survey questions were drawn from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Short

Form), the Pay Satisfaction Questionnaire, and Cohen’s Turnover Intention Scale. The

responses were analyzed using multiple linear regression analysis. The model was able to

predict employee turnover intentions significantly, F (2, 73) = 25.897, p <.001, R

2

= .415.

The recommendation for action is for dealership general managers to use the findings of

this study to form collaborations with dealership human resource partners to design and

implement transparent succession planning processes that promote pay and advancement

opportunities to reduce employee turnover intentions. The implication for positive social

change is the implementation of pay and succession structures that improve the

salesperson’s work experience, thus contributing to ongoing, lucrative employment

opportunities that contribute to and enhance the relationship between the dealership, retail

salespersons, and the community that they serve.

Relationship Between Opportunity for Advancement, Salary/Pay, and Retail Salesperson

Turnover Intentions

by

Edith M. Thompson

MHRM, Walden University, 2018

BBA, Austin Peay State University, 2016

Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Business Administration

Walden University

March 2023

Dedication

I want to dedicate this work to my parents, James and Mattie. I want to thank

them for always believing in me and encouraging me to use my head for something other

than a hat rack.

Acknowledgments

I want to acknowledge and thank everyone who was instrumental in completing

this journey. First, I would like to thank my biggest cheerleader, my husband, Adam.

Thank you for understanding late-night writing, missed family functions, and boxes of

articles and papers all over the house. Secondly, I want to acknowledge and thank my

chair, Dr. Laura Thompson. Thank you for your academic prowess and guidance. I would

not have completed this journey without our frequent conversations, our celebratory

wins, our step back and punt again sessions and the gentle encouragement of eating an ice

cream cone when we experienced success! You will forever be an instrumental part of

my life. I also want to thank my second committee member, Dr. Irene Williams. Thank

you for being the second set of eyes and ears of this study. Your advice and

encouragement were the touches needed to complete this journey. Lastly, I want to thank

all the Walden University faculty and staff who provided me with the tools, seminars,

residencies, and academic nuggets that made this journey less daunting. Thanks to all of

you, I am equipped to be a proud Walden University social change agent!

i

Table of Contents

List of Tables .......................................................................................................................v

List of Figures .................................................................................................................... vi

Section 1: Foundation of the Study ......................................................................................1

Background of the Problem ...........................................................................................1

Problem and Purpose .....................................................................................................3

Population and Sampling ...............................................................................................4

Population ............................................................................................................... 4

Sampling and Sample Size...................................................................................... 5

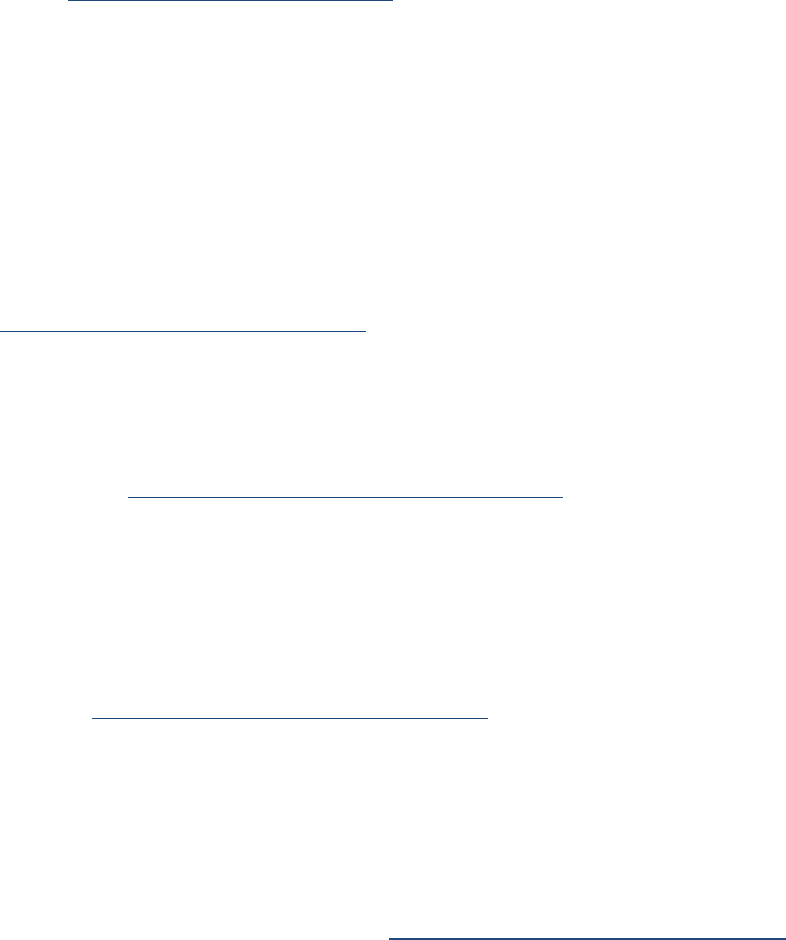

Figure 1 G *Power 3.1.9.2 Power Analysis for Study Sample Size ........................ 6

Nature of the Study ........................................................................................................6

Research Question and Hypotheses ...............................................................................7

Theoretical or Conceptual Framework ..........................................................................8

Operational Definitions ................................................................................................10

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations ..............................................................11

Assumptions .......................................................................................................... 11

Limitations ............................................................................................................ 12

Delimitations ......................................................................................................... 13

Significance of the Study .............................................................................................13

Contribution to Business Practice ......................................................................... 13

Implications for Social Change ............................................................................. 14

A Review of the Professional and Academic Literature ..............................................15

ii

Herzberg et al.'s Two-Factor Theory (Motivation-Hygiene Theory) ..........................17

Contrasting or Rival Theories ............................................................................... 21

Intrinsic Independent Variable: Opportunity for Advancement ........................... 30

Extrinsic Independent Variable: Salary/Pay ......................................................... 33

Dependent Variable: Employee Turnover Intentions ........................................... 35

Independent Variable Measurements .................................................................... 40

Dependent Variable Measurement ........................................................................ 43

Transition .....................................................................................................................44

Section 2: The Project ........................................................................................................47

Purpose Statement ........................................................................................................47

Role of the Researcher .................................................................................................48

Participants ...................................................................................................................49

Research Method and Design ......................................................................................50

Research Method .................................................................................................. 50

Research Design.................................................................................................... 51

Population and Sampling .............................................................................................53

Population ............................................................................................................. 53

Sampling Method .................................................................................................. 53

Sample size ........................................................................................................... 55

G*Power Analysis ................................................................................................ 55

Ethical Research...........................................................................................................56

Data Collection Instruments ........................................................................................58

iii

Demographic Survey ............................................................................................ 58

Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Short form) ............................................. 59

PSQ 60

Turnover Intention Scale....................................................................................... 62

Data Collection Technique ..........................................................................................63

Data Analysis ...............................................................................................................66

Assumptions .......................................................................................................... 67

Data Cleaning and Missing Information ............................................................... 69

Inferential Statistics and Interpretation ................................................................. 69

Study Validity ..............................................................................................................71

Internal Validity ...........................................................................................................71

Statistical Conclusion Validity ............................................................................. 71

Validity Threats .................................................................................................... 72

Instrument Reliability ........................................................................................... 72

Data Assumptions ................................................................................................. 73

Parametric assumption testing .............................................................................. 74

Sample Size ........................................................................................................... 74

External Validity ................................................................................................... 75

Transition and Summary ..............................................................................................76

Section 3: Application to Professional Practice and Implications for Change ..................78

Introduction ..................................................................................................................78

Presentation of the Findings.........................................................................................78

iv

Test of Assumptions ............................................................................................. 78

Demographic Statistics ......................................................................................... 83

Descriptive Statistics ............................................................................................. 83

Inferential Results ................................................................................................. 84

Opportunity for Advancement ............................................................................... 85

Salary/Pay ............................................................................................................. 85

Analysis Summary ................................................................................................ 86

Theoretical Conversation on Findings .................................................................. 87

Applications to Professional Practice ..........................................................................91

Implications for Social Change ....................................................................................92

Recommendations for Action ......................................................................................94

Recommendations for Further Research ......................................................................95

Reflections ...................................................................................................................96

Conclusion ...................................................................................................................98

References ..........................................................................................................................99

Appendix A: Permission to Use Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Short-Form

(1967) ...................................................................................................................137

Appendix B: Permission from H. G. Heneman to use Pay Satisfaction

Questionnaire (PSQ) 1985 ...................................................................................137

Appendix C: Permission to use Cohen (1999) Turnover Intention Scale ........................138

v

List of Tables

Table 1. Numerical Count and Percentage Values for Cited Sources .............................. 17

Table 2. Study Variables and Measurement Instruments with Permission to Use Status 63

Table 3. Collinearity Statistics for the Independent Variables ......................................... 80

Table 4. Correlation Coefficients Among Study Predictor Variables .............................. 80

vi

List of Figures

Figure 1. G *Power 3.1.9.2 Power Analysis for Study Sample Size .................................. 6

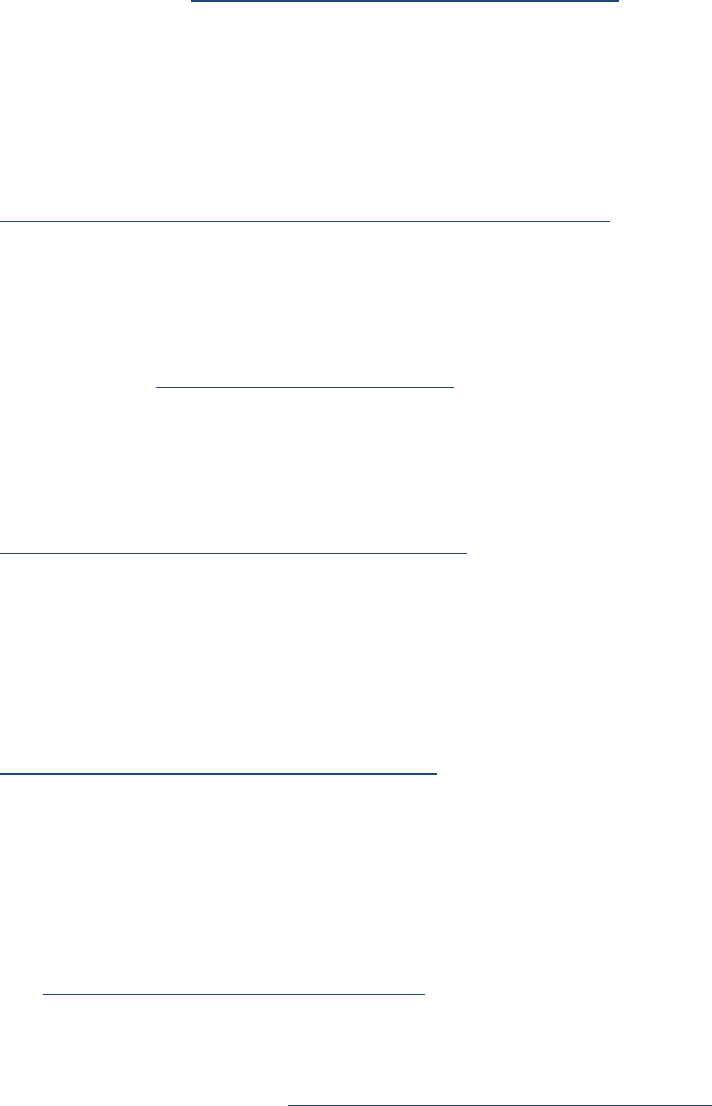

Figure 2. Herzberg et al.’s Two-Factor Theory of Motivation as it Applies to Employee

Turnover .................................................................................................................... 10

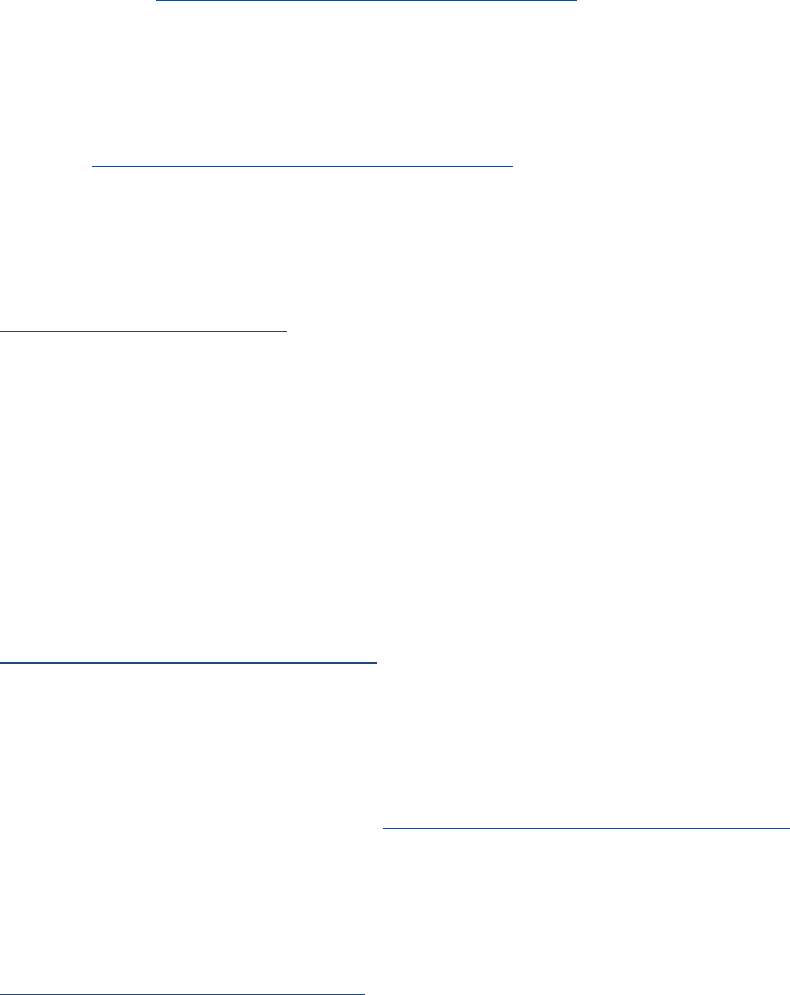

Figure 3. Illustration of Herzberg et al.’s (1959) Two-Factor Theory of Motivation ...... 21

Figure 4. Illustration of Maslow’s (1943) Hierarchy of Needs Theory ............................ 26

Figure 5. Illustration of Vroom’s (1964) Expectancy Theory .......................................... 28

Figure 6. Illustration of Deci and Ryan’s (1985) Self-determination Theory .................. 30

Figure 7. G* Power Priori Analysis for Sample Size ....................................................... 56

Figure 8. Scatterplot of Standardized Residuals ............................................................... 81

Figure 9. Normal P-P of the Regression Standardized Residuals ..................................... 82

1

Section 1: Foundation of the Study

Background of the Problem

Over the years, scholars have identified the intent to turnover and employee

turnover as recurring threats in retail sales-related positions. Scholars have suggested that

salesperson turnover substantially impacts organizational success and profitability

(Badrinarayanan et al., 2021; Fleming et al., 2022; Lai & Gelb, 2019; Lucas et al., 1987).

Lee et al. (2018) stated that employee turnover is a primary contributor to declined

business continuity and revenue loss, costing businesses nearly 200% in annual salary per

worker in worker replacement costs. Lai and Gelb (2019) further posited that the average

cost of sales turnover linked to forfeiture of recruitment funds, training costs, and direct

sales loss is $97,960 per salesperson, with it taking approximately 4 months to replace a

sales hire. Additionally, statisticians suggested that over 50% of currently employed retail

sales associates will leave their organizations in conjunction with the data presented in

the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS; 2018) annual report of total separations by

industry.

Retail sales organizations, such as automotive dealerships, heavily depend upon

their sales force. Fu et al. (2017) indicated that the retail sales employee is critical to

developing ongoing customer relationships, significantly enriching product loyalty and

future business growth. General managers generally compensate and advance high-

performing sales employees into dealership leadership positions that pay industry-leading

salaries. The BLS (2020) reported that 6% of the 4.5 million retail sales personnel in the

2

United States worked in automotive sales in 2018, with automotive dealers paying the

highest median hourly wage in the retail sales industry segment.

However, like other retail selling entities, the automotive sales industry is highly

cyclical and precipitously impacted by many internal and external threats that affect job

satisfaction and turnover intentions (Jaura, 2020; Lai & Gleb, 2019; McNeilly & Russ,

1992). High turnover among automotive retail sales employees leads to loss of vehicle

sales, diminished consumer confidence in the dealership and brand, reduction in the talent

pool, and inflated dealership costs associated with recruiting, hiring, and training (Al

Mamun & Hasan, 2017; Fu et al., 2017). Competent and talented sales employees may

consider leaving the dealership when specific intrinsic (e.g., opportunity for

advancement) and extrinsic (e.g., salary/pay) motivational job satisfaction factors are not

met. Nonetheless, the BLS (2018) predicted that between 2018 and 2028, retail sales

management jobs would experience a 5% growth, statistically demonstrating the

importance of employee retention and advancement initiatives in retail sales. In

conjunction with the BLS calculations, industry statisticians forecasted that new vehicle

revenue would reach $945.9 billion over the next 5 years, with recent vehicle sales

accounting for 50.8% of total industry revenue.

Automotive dealership general managers need to understand the concept of

intrinsic and extrinsic job motivators that contribute to job satisfaction or dissatisfaction

in the automotive retail sales work environment. General managers who understand and

analyze the constructs that may contribute to the retail sales employee’s intent to turnover

and any possible relationships between these characteristics can prove vital to dealership

3

success and protect the dealership’s competitive advantage (Agarwal & Sajid, 2017).

Conversely, many dealership leaders and managers need to understand or recognize the

relationship between intrinsic motivators, such as the opportunity for advancement, and

extrinsic hygiene factors, such as salary or pay, and whether these constructs significantly

predict employee turnover intention among automotive retail salespeople. Automotive

retail sales are a substantial contributor to the U.S. economy, and the retail sales

employee is the most consumer-trusted facilitator for the sales transaction (Friend et al.,

2018). Therefore, automotive dealership general managers must develop processes that

appeal to sales personnel’s intrinsic job satisfiers (i.e., motivators) and address extrinsic

job dissatisfiers (i.e., hygiene) to reduce turnover intentions and encourage sales

employee retention. In this study, I examined to what degree the intrinsic job satisfier of

opportunity for advancement and extrinsic job dissatisfier of salary/pay predict retail

sales employee turnover intention in the automotive sales industry. I expected this study

to contribute confidently to the literature’s broad gap regarding employee turnover

intention in the automotive sales industry.

Problem and Purpose

Organizational leaders across various industries recognized employee turnover

intention as the principal antecedent and predictor of employee turnover behavior, a

substantial threat to current and future organizational performance (Aburumman et al.,

2020; Belete, 2018; Lee et al., 2018; Sanjeev, 2017). The retail sale employee’s intention

to turnover endangers the retail sales organization’s profitability, with employee

replacement costs as high as $10,000 per replaced employee, almost equaling double the

4

annual salary of the replaced employee (Belete, 2018; Chhabra, 2018; Olubiyi et al.,

2019; Oruh et al., 2020). The general business problem was that employer turnover

intention among retail sales employees in the automotive sales industry could become a

costly problem that affects dealership profitability, performance, and competitive

advantage. The specific business problem was that many automotive dealership general

managers need to understand the relationship between the intrinsic job satisfier of the

opportunity for advancement, the extrinsic job dissatisfier of salary/pay, and employee

turnover intention.

The purpose of this quantitative correlational study was to examine the

relationship between the intrinsic job satisfier of the opportunity for advancement, the

extrinsic job dissatisfier of salary/pay, and employee turnover intention. The independent

or predictor variables were an opportunity for advancement and salary/pay. The

dependent or criterion variable was employee turnover intention. The implications for

positive social change include developing a mutually constructive relationship between

the dealership and the community it serves. This reciprocally valuable relationship could

contribute to employee stability, new job opportunities, and local community economic

growth associated with increased vehicle sales and registrations, such as local tax revenue

and charitable contributions to local community organizations.

Population and Sampling

Population

The population for this study were franchised new and used car salespersons in

dealerships located in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Alabama. The participants were retail

5

sales employees who fit all-gender specifications and were at least 21 years of age, with 1

year or more of retail selling experience in the automobile dealership environment. The

participants were full-time retail sales employees who sell vehicles only. The retail sales

employees did not comprise other sales-related positions within the dealership structure,

such as parts salespeople, service salespeople, or financial products salespeople.

Sampling and Sample Size

I used the nonprobabilistic convenience sampling method to select retail sales

employees who matched the inclusion criteria of this study. This sampling method

allowed me to target participants via online surveys and was both time-saving and cost-

effective (Etikan et al., 2016; Rahi, 2017). The G*Power 3.1 power analysis program was

the most applicable test for determining this study’s minimum and maximum sample

size. I conducted an a priori analysis with an effect size f = 0.15, an a = 0.05, and a power

level of 0.80 to determine the minimum sample size of 68 participants and a power level

of 0.99 to determine the maximum sample size of 146 participants. Therefore, the

appropriate sample size for this study ranged from 68 to 146 participants. Figure 1

illustrates the G *Power 3.1.9.2 power analysis results for the sample size calculations.

6

Figure 1

G *Power 3.1.9.2 Power Analysis for Study Sample Size

Nature of the Study

I chose a quantitative research methodology to examine the business phenomenon

in this study. There are several methodologies researchers can employ to examine or

explore their phenomenon; however, I considered the three primary methods to examine

or explore this business phenomenon (see Ellis & Levy, 2009; Saunders et al., 2016).

Researchers use qualitative methods to explore the business process’s philosophical,

subjective, and perceptive nature (Ellis & Levy, 2009; Murshed & Zhang, 2016;

Saunders et al., 2016). Researchers seeking to examine or test hypotheses employ the

quantitative method to numerically represent the generalizability, causality, or scale of

effects between the independent and dependent variables (O’Leary, 2017; Sligo et al.,

2018). Researchers who cannot collect additional insight from quantitative or qualitative

findings may implement a combination of quantitative and qualitative attributes or a

mixed-methods methodology (Saunders et al., 2016; Sligo et al., 2018). Since the

philosophical and explorative qualitative feature was absent from this study and the

0.5 0.55 0.6 0.65 0.7 0.75 0.8 0.85 0.9 0.95

0

20

40

60

80

100

Total sample size

= 0.15

Effect size f²

F tests - Linear multiple regression: Fixed model. R² deviation from zero

Number of predictors = 2. α err prob = 0.05. Effect size f² = 0.15

Power (1-β err prob)

7

mixed-methods methodology was not congruent with my research question (see Sligo et

al., 2018), I did not implement a qualitative or mixed-methods approach. In this study, I

tested hypotheses and conducted numerical calculations to determine to what degree an

intrinsic job satisfier (i.e., opportunity for advancement) and an extrinsic job dissatisfier

(i.e., salary/pay) significantly predicted employee turnover intention; therefore, a

quantitative methodology was the most appropriate method for this study.

The three quantitative research designs are descriptive, experimental, and

correlational (Saunders et al., 2016). Researchers use the descriptive design to explore or

describe the phenomenon without statistical inference (Siedlecki, 2020). Researchers

interested in the causal relationship of the variables in a controlled environment apply an

experimental design (Armstrong & Kepler, 2018; Saunders et al., 2016; Zellmer-Bruhn et

al., 2016). Researchers employ the correlational design to ascertain the degree of

noncausal strength to predict a relationship between two or more variables (Curtis et al.,

2016; Seeram, 2019). I chose the correlational design because the objective was to

investigate the extent to which a statistically negative or positive linear correlation exists

between the independent and dependent variables. The descriptive and experimental

designs were inappropriate for this study because I was not observing, describing, or

drawing a causal inference.

Research Question and Hypotheses

The research question for this study was: Within small to medium franchise new

car dealerships, what is the relationship between the intrinsic job satisfier of the

8

opportunity for advancement, the extrinsic job dissatisfier of salary/pay, and employee

turnover intention?

H

0

: There is no statistically significant relationship between the intrinsic job

satisfier of the opportunity for advancement, the extrinsic job dissatisfier of

salary/pay, and employee turnover intentions.

H

1

: There is a statistically significant relationship between the intrinsic job

satisfier of the opportunity for advancement, the extrinsic job dissatisfier of

salary/pay, and employee turnover intentions.

Theoretical or Conceptual Framework

I selected Herzberg et al.’s (1959) two-factor theory of motivation or motivation-

hygiene theory as the theoretical framework for this research study (see Gardner, 1977;

Herzberg et al., 2017; Tan & Waheed, 2011). Herzberg et al. (2017) theorized that work

motivation encompassed two sets of characteristics associated with job satisfaction or

dissatisfaction (Alshmemri et al., 2017; Gardner, 1977). Herzberg et al. (2017) identified

job satisfiers with intrinsic motivators, such as recognition, advancement, and

responsibility, while classifying job dissatisfiers with extrinsic hygiene work factors, such

as salary, pay, compensation, benefits, and job security (Hur, 2018). Herzberg et al.

(2017) postulated that intrinsic motivators stimulated positive job satisfaction produced

by the natural conditions resulting from the job itself (Hur, 2018; Tan & Waheed, 2011).

Similarly, Herzberg et al. postulated that the shortage or absence of extrinsic factors

linked to working conditions, such as salary, compensation, benefits, and work

conditions, contribute to job dissatisfaction (Hur, 2018). In contrast, in the hierarchy of

9

needs theory, Maslow (1943) argued that basic human needs, such as safety or the need

to eat, are some of the driving forces behind job motivation. In expectancy theory, Vroom

(1964) interjected the construct of motivational force generated by expectancy (i.e., effort

will equal outcome), valance (i.e., desire for expected result), and instrumentality (i.e.,

achieved outcome will equal the desired reward) as a job motivator (Baciu, 2017; Lloyd

& Mertens, 2018).

I chose to use Herzberg et al.’s (1959) two-factor theory as the theoretical lens to

examine the independent variables, intrinsic job satisfier (i.e., opportunity for

advancement) and extrinsic job dissatisfier (i.e., salary/pay), measured by the Minnesota

Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short Form (MSQ-SF), and the Pay Satisfaction

Questionnaire (PSQ; see Heneman & Schwab, 1985; Morgeson et al., 2001; Weiss et al.,

2010). Cohen (1999) developed an adaptive employee turnover decision process model

based in Mobley’s (1978) intent to leave scale, that was applicable to any work

environment and measured employee turnover intention using intrinsic and extrinsic job

satisfaction and dissatisfaction experiences. Cohen’s turnover intention scale is the

chosen instrument for measuring this study’s dependent variable. Sager et al. (1988)

employed Mobley’s model to measure turnover intentions among retail salespeople from

different industries. Therefore, as applied to this study, I expected the independent

variables to predict turnover intention. In recent studies, researchers revealed that job

satisfaction is critical to employee turnover across various industries (Guha &

Chakrabarti, 2015; Hur, 2018; Tan & Waheed, 2011; Voight & Hirst, 2015).

Furthermore, these researchers also concluded that the multiple constructs, singularly or

10

in correlation with each other, predicted either a negative or positive relationship with

employee turnover intention. Figure 2 illustrates Herzberg et al.’s two-factor theory of

motivation as it applies to employee turnover intentions.

Figure 2

Herzberg et al.’s Two-Factor Theory of Motivation as it Applies to Employee Turnover

Operational Definitions

Employee turnover: The act of an employee leaving or exiting an organization

(Fang et al., 2018).

Extrinsic job satisfaction: How an employee feels about their work situation

includes supervision, work conditions, coworkers, company policies, job security,

worker’s personal life, and salary/pay (Hur, 2018; Tepayakul & Rinthaisong, 2018).

Job satisfaction: The positive or negative attitudes or feelings an employee has

towards their job or place of employment (Tepayakul & Rinthaisong, 2018).

Intrinsic job satisfaction: The way an employee feels about and is motivated by

the nature of the job itself, including achievement, recognition, responsibility, growth,

and the opportunity for advancement (Hur, 2018; Tepayakul & Rinthaisong, 2018).

Retail sales employee: The employee who assists retail customers with finding

and selecting their desired product by answering product questions, demonstrating

Employee

turnover

intention

Opportunity

for

Advancement

Intrinsic Job

Satisfier

Salary / Pay

Extrinsic Job

Dissatisfier

11

product features and benefits, and processing customer payments for the selected product

(BLS, 2018).

Separation rate: The total annual separations as a percentage of annual average

employment (BLS, 2018).

Turnover intention: An employee’s conscious decision to begin the process of

thinking about leaving the job, looking for a new job, or leaving the job (Aburumman et

al., 2020).

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations

The assumptions, limitations, and delimitations are the research elements that are

either controlled or not controlled by the researcher (Saunders et al., 2016). These

elements are essential to establishing research relevance, credibility, and reliability

(Saunders et al., 2016). Ellis and Levy (2009) emphasized that researchers who need to

articulate these vital research elements clearly could generate uncertainty and reduce

credibility within their research; however, researchers can use the assumptions,

limitations, and delimitations to clarify vague presuppositions and identify future

research opportunities.

Assumptions

The researcher utilizes the assumptions section of the research study to

communicate what they assume and accept to be true without any formidable evidence

from the limited knowledge and probabilities of the theory and practices (Ellis & Levy,

2009; Waller et al., 2017). I assumed that I received the required number of surveys to

produce reliable data analysis results and that there were no missing responses to survey

12

questions. I further assumed that the study participants provided open and honest

feedback to all survey questions. I alleviated any apprehensions with these two

assumptions by emphasizing that the survey was strictly voluntary, anonymous, and

designed to protect participants from the perceived repercussions of the dealership

management personnel. I, therefore, created an atmosphere for open and honest responses

from all qualified participants.

Another assumption was that all participants were automotive retail sales

employees. The study did not include (a) automotive parts sales managers; (b)

automotive parts sales employees; (c) automotive accessory sales employees; (d)

automotive finance managers; (e) automotive service department managers; or (f)

automotive services department employees, such as mechanics, porters, and service

writers. Participants from other dealership departments would alter research findings and

render the study invalid and unreliable (Cerniglia et al., 2016). To mitigate any issues

associated with surveying the wrong participants, I clearly and concisely emphasized the

research study’s purpose and the dealership role characteristics of the participants.

Limitations

Limitations represent the circumstances that are not under the researcher’s

control, which may introduce potential weaknesses and compromise research methods

and analysis (Waller et al., 2017). The first limitation was the inherently limited nature of

the correlational design. The correlational design cannot be used to extrapolate or

conclude the cause and effect between the variables (Rugg, 2007; Saunders et al., 2016).

13

Therefore, I only employed the correlational design to predict the level of interaction

between the variables but not to assess causation.

The second limitation of the research study was achieving a sufficient sample size

for reduced biases, validity, and generalization of the findings (see Cerniglia et al., 2016).

The use of an online survey produced the level of participation required to satisfy the

large sample size needed to conduct quantitative research that generated valid, reliable,

and unbiased findings.

Delimitations

The researcher uses delimitations to indicate the study’s boundaries and scope

(Waller et al., 2017). The delimitations of this study included the geographical locations

of the dealerships in only three states within the continental United States: (a) Tennessee,

(b) Kentucky, and (c) Alabama. The scope of the study was set to examine small, strictly-

to medium-sized, privately owned automotive dealerships, excluding all (a) large,

publicly traded automotive dealer groups; (b) large (i.e., having more than 200

employees), privately owned dealerships; and (c) online automotive vendors.

Significance of the Study

Contribution to Business Practice

The relationship between the customer and the retail sales employee is the most

influential element in the customer’s purchasing decision (Edmondson et al., 2019). As

the most trusted member of the selling organization, the retail sales employee is a

fundamental link to organizational performance and profitability (Friend et al., 2018).

U.S. businesses spend approximately $800 billion on various incentives designed to

14

retain retail sales force employees and lessen turnover (Sunder et al., 2017). Automotive

dealership general managers can apply the findings of this study to identify, design, and

implement positive organizational practices that may reduce employee turnover

intentions. These practices can include initiatives such as (a) performance-based pay

plans, (b) monetary incentives for elevated customer service indexes, and (c) a future

leader succession plan for top performers. Implementing these strategies may assist

dealership general managers with controlling lost sales revenue, regaining competitive

advantage, and solidifying consumer trust. Therefore, this study contributes to business

practice by providing new information on retail sales employee turnover intention and

helping dealership general managers better understand a possible relationship between

the opportunity for advancement, salary/pay, and employee turnover intentions.

Implications for Social Change

Automotive dealership general managers operate small to large businesses that

service various communities and can be significant community stakeholders. The BLS

(2019) reported that automobile dealers are the fifth top-paying industry for retail sales

employees. Dealership general managers can utilize their lucrative role as community

stakeholders to promote community programs and local social enterprises (Park &

Campbell, 2018). Dealership general managers that embrace the role of a viable

community conscience partner can enable the community stakeholder culture and use this

position to develop jobs and training opportunities that encourage amplified employment

and work opportunities for the community workforce. Dealership general managers can

engage their stakeholder position to create community opportunities that promote and

15

demonstrate corporate social responsibility, including charitable donations to programs

that support employee and community well-being. Dealership general managers can

utilize the findings of this study to improve their current knowledge concerning employee

retention benefits. They can use the results to develop programs and processes to

decrease employee turnover intention, lower community unemployment rates, generate

steady wages, and create a constant influx of tax revenue (see Park & Campbell, 2018).

Dealership general managers can also use the findings of this study to validate the

business need for supporting mentorship programs that offer community-based talent

from local high schools, technical colleges, 4-year colleges, and vocational rehabilitation

centers exclusive access to job openings within the dealership. The dealership’s general

manager can use these programs to secure top-level local talent, which boosts the

dealership’s community stakeholder position and promotes the overall future success of

the dealership and the community it serves.

A Review of the Professional and Academic Literature

The review of the professional and academic literature encompassed current and

seminal research from peer-reviewed journals, scholarly books, government agency

publications, and industry-specific publications for the examination of the relationship

between the independent variables of intrinsic job satisfaction (i.e., the opportunity for

advancement) and extrinsic job dissatisfaction (i.e., salary/pay) and the dependent

variable of retail employee turnover intention. In the review, I also incorporated current

and seminal literature that examined the strengths, weaknesses, and limitations of

Herzberg et al.’s (1959) two-factor theory of motivation (i.e., Herzberg, 1965; Hur, 2018;

16

Tan & Waheed, 2011), which was the primary theoretical lens for the study. The review

includes comprehensive research of divergent or rival theories, such as Deci and Ryan’s

(1985) self-determination theory, Vroom’s (1964) expectancy theory (Baciu, 2017; Lloyd

& Mertens, 2018), and Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs theory. Additional

components of the literature review include literature that establishes the reliability and

validity of the psychometrical scales employed to measure the chosen independent

variables, (a) opportunity for advancement (i.e., the MSQ-SF; see Weiss et al., 2010), and

(b) salary/pay (i.e., the PSQ; see Heneman & Schwab, 1985; Morgeson et al., 2001), as

well as Mobley et al.’s (1979) turnover intentions model (see Sager et al., 1988), that

measures the dependent variable of (c) employee turnover intention.

I searched the following databases in Walden University’s library for peer-

reviewed articles and books published within 5 years of expected chief academic officer

approval, with the frequency of those sources listed in Table 1: ABI/Inform Complete,

Academic Search Complete, Business Source Complete, eBook Collection (EBSCOhost);

Emerald Management, ERIC, IBISWorld, PsycINFO, PsycTESTS, SAGE Journals,

ScholarWorks, Science Direct, Taylor and Francis Online, and Walden Library Books. I

used the Boolean identifiers and/or, which assisted in achieving the optimal results using

the following key search words or terms: employee turnover intention, employee

turnover, turnover intentions, automotive retail sales, retail sales, salesperson,

automotive salesperson, Herzberg's theory, two-factor theory, job satisfaction, job

dissatisfaction, pay, promotion, career advancement, advancement, extrinsic motivation,

intrinsic motivation, retail turnover, sales turnover, employee advancement, employee

17

salary, employee pay, employee promotion, involuntary turnover intention, and voluntary

turnover intention.

Table 1

Numerical Count and Percentage Values for Cited Sources

Source

Older than

6 years

Within 5

years or less

Total

Percentage

Books

7

6

13

5.2%

Peer-reviewed articles

69

159

228

91.5%

Government

1

4

5

2.2%

Other

0

2

2

1%

Total

77

171

248

100%

Note: This table denoted compliance with university guidelines for reference and cited

sources.

Herzberg et al.'s Two-Factor Theory (Motivation-Hygiene Theory)

Herzberg et al.’s (1959, 2017) two-factor or motivation-hygiene theory served as

this study’s theoretical framework or lens. In 1959, Frederick Herzberg utilized the

critical-incident method to interview engineers and accountants in Pittsburg,

Pennsylvania. Herzberg et al. (1959) asked the participants to recount incidences where

they felt extremely good or bad about their jobs. The researchers then posited that worker

satisfaction is primarily generated from several crucial constructs that promote and

produce either job satisfaction or dissatisfaction (Alshmemri et al., 2017; Gardner, 1977;

Herzberg et al., 2017; Hur, 2018; Tan & Waheed, 2011; Ward, 2019). Zhang et al. (2020)

discussed that Herzberg et al.’s research was based on the construct of work, the

employee’s attitude towards work, and the effect the work perspective produced

18

regarding job satisfaction or dissatisfaction. The various seminal and recent examinations

and explorations of this theory prove that Herzberg et al.’s motivation-hygiene theory is

relevant in today’s workplace.

Herzberg et al. (1959, 2017) identified job satisfaction or intrinsic motivation

factors as (a) achievement, (b) recognition, (c) advancement, (d) growth, (e) work-itself,

and (f) responsibility (Hur, 2018; Tan & Waheed, 2011; Ward, 2019). Whereas the

fundamental factors of job dissatisfaction or extrinsic hygiene factors, Herzberg et al. and

Ward (2019) identified as (a) supervision, (b) salary/pay, (c) work conditions, (d)

interpersonal relationships, and (e) company policies. Herzberg et al. (1959), Ann and

Blum (2020), and Zámečník and Kožíšek (2021) postulated that the absence or shortage

of extrinsic hygiene factors influenced job dissatisfaction but that those factors were not

the primary creators of dissatisfaction. Employees could feel job dissatisfaction even

when extrinsic or hygiene constructs were in place; however, hygiene-oriented

constructs, such as stressful interpersonal relationships with fellow workers or

management and company policies, produced dissatisfaction and decreased motivation

(Alrawahi et al., 2020). Herzberg et al. (1959) further added that intrinsic motivators

inspired job satisfaction and that the experience of job dissatisfaction and job satisfaction

were two different phenomena or feelings (Zhang et al., 2020). Herzberg (1965) stated

that job satisfaction and dissatisfaction are not opposite entities. Zhang et al. (2020)

postulated that the contrasting position to job satisfaction is no job satisfaction, not

dissatisfaction, which generated different performance outcomes. When job

dissatisfaction is not present, that does not denote that job satisfaction is present; it

19

suggests the employee is not satisfied with the job (Oluwatayo, 2015; Wilson, 2015).

Organizational leaders can use this valuable data to evaluate intrinsic and extrinsic factors

influencing employee turnover intentions and increasing retention.

Herzberg et al. (1959) found that intrinsic motivators, such as the opportunity for

advancement, are components of the theory that provide employees with long-term

performance results. The achievement factor proved to be an essential satisfier with the

highest frequency in long-range (38%) and short-range (54%) high attitude sequences

(Herzberg et al., 1959). Herzberg et al. further explained that extrinsic hygienic factors,

such as salary/pay, produce short-term effects that affect overall employee job

perceptions, attitudes, and performance (Herzberg, 1965). In a study surveying Malaysian

retail salespeople, Tan and Waheed (2011) reported similar results, discovering a

statistically significant relationship between job satisfaction and extrinsic hygienic job

motivators, such as working conditions, company policy, and salary/pay.

Herzberg et al. (1959) posited that intrinsic motivators encouraged job

satisfaction, resulting from the job itself. Herzberg et al. postulate that job content

generated job satisfaction indicate that employees can accomplish elevated job

satisfaction levels when achieving their goals. This attitude toward job content can

provide employers with employees who demonstrate positive work behaviors, which

leads to enhanced productivity and employee retention (Herzberg et al., 1959). However,

Herzberg (1965) theorized that extrinsic factors associated with job contexts, such as

salary/pay, working conditions, and security, are directly controlled by the employer,

20

directly related to job dissatisfaction, and indirectly related to the employee’s overall job

performance.

Herzberg et al. (1959) found that positive customer relationships were critical to

providing motivation and job satisfaction among those studied. The participants indicated

having the ability to control their time via scheduling and having open communication

lines with the customer-generated feelings of job satisfaction (Herzberg et al., 1959).

Additional researchers applying Herzberg et al.’s two-factor theory found that retail

salespersons are highly motivated by intrinsic motivating factors, such as achievement

and advancement; however, the extrinsic hygiene factor of salary pay was the second

highest-rated motivator among retail salespersons (Tan & Waheed, 2011; Winer &

Schiff, 1980). Tan and Waheed (2011) further posited that retail store managers should

design and implement salesperson reward initiatives that endorse extrinsic and intrinsic

elements, such as work conditions, recognition, salary/pay, and company policies, to

generate high levels of job satisfaction. Researchers indicated that sales managers should

strive to ensure salesperson satisfaction and happiness and postulated that salespeople

satisfied with their job would communicate their satisfaction to potential new employees

and customers and perform better in their roles (Lai & Gelb, 2019; Prasad Kotni &

Karumuri, 2018; Tan & Waheed, 2011). Furthermore, since the customer is the primary

focus of the retail salesperson and the sole source of income in most cases, initiatives

designed to enhance the retail sales employee’s satisfaction would boost their satisfaction

and the satisfaction of the consumer and workplace morale.

21

Prasad Kotni and Karumuri (2018) tested retail outlet employee provocation using

Herzberg et al.’s (1959) two-factor theory, finding that extrinsic rewards were

significantly preferred over intrinsic rewards, increasing productivity and job satisfaction.

Ziar and Ahmadi (2017) hypothesized that motivational factors differed according to the

employee’s age. Ziar and Ahmadi concluded that intrinsic factors, such as opportunities

for advancement, significantly influenced younger employees. In contrast, older

participants were prone to extrinsic hygienic factors, such as salary/pay.

Figure 3

Illustration of Herzberg et al.’s (1959) Two-Factor Theory of Motivation

Note. This figure illustrates how the constructs of the two-factor theory of motivation

interact to create job satisfaction or dissatisfaction.

Contrasting or Rival Theories

Herzberg et al.’s (1959) two-factor theory aims to identify what process or

content will generate job satisfaction or dissatisfaction in conjunction with other

motivational-based views. Herzberg et al. theorized that the intrinsic factors of (a) career

advancement, (b) achievement, (c) recognition, (d) work itself, (e) responsibility, and (f)

Extrinsic Dissatisfiers

• Pay/salary

• Working conditions

• Company policies

• Supervision

• Job security

• Work life balance

Intrinsic Satisfiers

• Opportunity for advancement

• Recognition

• Growth

• Status

• Challanging work

• Promotion

• Sense of personal achievement

22

growth possibilities increase job satisfaction. However, the extrinsic or hygiene factors of

(a) salary/pay, (b) organizational policies and procedures, (c) relationship with

supervisor, (d) interpersonal relationships, and (e) working conditions can reduce job

satisfaction. Herzberg (1965) opined that these extrinsic and intrinsic factors share an

inverse relationship where the absence of hygiene factors decreases motivation, but

inherent or intrinsic factors will stimulate motivation when present.

Herzberg et al.’s (1959) two-factor theory and Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of

needs theory are similar in that both are examples of content theories. Content theories

investigate the internal qualities a person uses or possesses to stimulate personal

motivation (Issac et al., 2001). Contrastingly, Vroom’s (1964) expectancy theory is a

process theory. Vroom’s expectancy theory investigates an individual’s logical process to

make conscious choices that provide them with a specific expected outcome: pleasure or

pain. Vroom's expectancy theory is contrary to Herzberg et al. and Maslow’s hierarchy of

needs theory in that it is not based on the satisfaction of individual needs. However,

Harris et al. (2017) opined that Vroom’s expectancy theory is based on the direct

outcomes of individual behaviors resulting from their decision expectations. In their self-

determination theory, Deci and Ryan (1985) suggested that an employee’s inherent

tendencies of growth and psychological needs dictated intrinsically or extrinsically

motivating attributes toward autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Szulawski et al.

(2021) and Wingrove et al. (2020) posited that intrinsic motivation is encouraged by

internal rewards and linked to performance prediction or enhancement.

23

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory

Maslow (1943) identified five immediate human needs as motivators (Güss et al.,

2017) and categorized those needs as (a) physiological, (b) safety, (c) self-esteem, (d)

growth or self-actualization, and (e) love. Unlike Maslow, Herzberg et al. (1959) centered

their theory around the fundamental thesis that employee motivation is based on extrinsic

and intrinsic rewards or recognition. No sequence of extrinsic or intrinsic rewards leads

to the principal cause. However, Maslow postulated that motivation was established on

personal needs and satisfaction and opined that these needs followed a sequenced

hierarchal path that led to the highest form of motivation fueled by self-actualization.

In the hierarchy of needs theory, Maslow (1943) posited that physiological needs

essential for basic human survival, such as air, water, and food, were the most basic

conditions and formed the foundation for higher-level needs satisfaction. Maslow (1970)

stated that once a human’s basic needs were met, safety and security, or the need to avoid

physical or psychological danger, were next in the hierarchy. The need for safety and

security is followed by love or longing for affection and support. Individuals who feel

valued and supported become confident and robust, satisfying their sense of belonging

and need for admiration or love (Güss et al., 2017; Maslow, 1943). Once these lower

needs are met, then the higher conditions become achievable (Güss et al., 2017; Maslow,

1943), giving way to a person’s need to be the best they can be or, as Maslow (1943) and

Guss et al. (2017) labeled it, the desire for self-fulfillment or self-actualization.

Maslow (1943) opined that the five needs correlated with each other. The higher-

level needs could not be fulfilled if the lower conditions remained not satisfied, and

24

recent research supported this hypothesis (Kanfer et al., 2017; Siahaan, 2017). Kanfer et

al. (2017) postulated that managers or business leaders who develop workplace initiatives

that meet the needs Maslow identified in the theory position their organizations for high

levels of employee job satisfaction and low employee turnover. Kanfer et al. and Siahaan

(2017) suggested that job dedication decreases turnover intentions. Therefore,

organizational leaders can use Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory to deduce that

employees who achieve self-actualization will also experience elevated job satisfaction

levels and diminished turnover intentions.

Various researchers have challenged the physiological need hypothesis posited by

Maslow. These researchers presented theories and cases demonstrating that more than

bare human essentials were needed to propel human motivation. Alam et al. (2020)

opined that wages were the most significant contributor to employee work motivation

versus trust and safe work environments. In contrast, Criscione-Naylor and Marsh (2021)

found that since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, employees have been significantly

motivated by the organization’s ability to provide a secure and safe workplace. The

researchers showed that motivational needs differ from one employee to the next.

Organizational size and location are vital in establishing a workplace hierarchy (Jonas et

al., 2016). Stewart et al. (2018) further posited from data generated by studies conducted

with Southwest Airlines, Valve Software, and Google that companies that satisfy the

upper levels of the hierarchy, self-actualization, and self-esteem create a workplace

environment that encourages job security while meeting an employee’s need for

25

emotional compensation and satisfying physiological and safety requirements with

monetary compensation.

Recent researchers demonstrated how Maslow's theory applied to higher

education institutes students. Abbas (2020) posited that higher education institutes

provide students with basic education needs, such as a safe campus, state-of-the-art

facilities, teaching quality, employability, and extracurricular activities, which support

Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory. Abbas opined that students are motivated to

participate in activities that promote personal development and enhance leadership skills.

Therefore, it demonstrates that when students' basic needs are satisfied, this satisfaction

encourages them, boosts self-esteem, and creates self-actualization. However, Maslow

(1943) viewed self-actualization from a personal perspective since this attribute could

possess varying characteristics instituted in the individual's personality (Compton, 2018).

Some researchers further proposed that some individuals do not have the drive or want to

reach self-actualization (Kaufman, 2018). In contrast to Herzberg et al. (1959), Alrawahi

et al. (2020) suggested that intrinsic motivating factors prompt individual progress and

create a desire for career advancement and recognition.

26

Figure 4

Illustration of Maslow’s (1943) Hierarchy of Needs Theory

Vroom's Expectancy Theory

Vroom (1964) theorized that employees would choose specific actions expecting

a particular result or outcome, pleasure or pain. Vroom viewed motivation as a force and

defined motivational force as the resultant product of (a) expectancy, (b) instrumentality,

and (c) valence (Baciu, 2017; Lloyd & Mertens, 2018; Kumar & Prabhakar, 2018).

According to Vroom, expectancy is an employee's anticipation of the performance results

produced by a conscious, deliberate action on their part. (Baciu, 2017; Lloyd & Mertens,

2018; Pereira & Mohiya, 2021)) Furthermore, Baciu (2017), Lloyd and Mertens (2018),

and Pereira and Mohiya (2021) postulated that Vroom viewed expectancy as an action-

outcome association that takes on the values of 0 (no expectation) to 1 (full expectation),

which correlated with the employee's belief that their efforts would generate the expected

result. Vroom defines the construct of instrumentality as the perception that an

anticipated reward will result from the performance. Vroom described this as an

Self Actualization

Esteem Needs

Social Needs

Safety Needs

Basic Needs

27

outcome-outcome association with the same outcome designation values; 0 (no

probability of reward delivery) to 1(reasonable probability of reward delivery); (Baciu,

2017; Lloyd & Mertens, 2018). Vroom described valance as indicating the individual's

degree of preference toward the subsequent outcome or reward (Lloyd & Mertens, 2018).

These rewards could be positive, such as an increase in pay, or negative income, such as

penalties or sanctions (Baciu, 2017). This view contrasts with Herzberg et al.'s (1959)

theory, which focused on employees' intrinsic and extrinsic individual needs that

influence job satisfaction or dissatisfaction, not just the individual motivational results

and actions spurred by a personal decision and the ensuing outcome.

Researchers inferred a significant association between employee personality,

career development, work motivation, and employee retention. Kumar and Prabhakar

(2018) discovered that workplace motivation strategy centered on initiatives that promote

career development and rewards based on employee career planning and development

increased employee motivation levels, providing organizational leaders with a preface for

implementing personality analysis as motivational human resource management policies.

Waltz et al. (2020) revealed the motivational value professional development initiatives

had in improving retention and performance among millennial nurses. Organizational

leaders who embrace employee initiatives or rewards that yield positive results and

reduce adverse effects could increase employee motivation and promote retention.

Motivated employees who are productive and have specific career goals or

outcomes are easy to retain. Kanfer et al. (2017) investigated goal choice and how it

influences employee motivation, applying Vroom's expectancy theory as their theoretical

28

lens. The researchers argued that work outcomes could impact employee job satisfaction

and their decisions not to stay with an organization. Kanfer et al. demonstrated that

motivation is a direct result of goal-orientated resources, and when employees achieve

goal accomplishment, retention increases, and employees readily accept organizational

work goals. Vroom (1964) hypothesized that the results of motivational force influenced

employee behavioral outcomes. Corporate leaders can implement employee initiatives or

rewards into career development and advancement opportunities that encourage

individuals to engage in behaviors that generate the expected positive results associated

with increased employee motivation (Baciu, 2017). Employee productivity and job

effectiveness are crucial links to overall job fulfillment and organizational effectiveness

(Kumar & Prabhakar, 2018; Prentice & Thaichon, 2019), supporting a portion of

Herzberg et al.’s (1959) two-factor theory regarding intrinsic motivators.

Figure 5

Illustration of Vroom’s (1964) Expectancy Theory

Self-determination Theory

Deci and Ryan (1985) postulated that extrinsic motivation could be internalized,

and as extrinsic rewards increased over a prolonged period, extrinsic motivation became

• Effort

Expectancy

• Performance

Instrumentality

• Reward

• Outcome

Valance

Motivation

29

autonomous. According to Deci and Ryan, intrinsic motivation is the individual’s natural

tendency to learn and to search for new challenges based on their interests and passions,

whereas extrinsic motivators are viewed as external regulations generated by external

rewards, punishment, or amotivation (Grabowski et al., 2021; Szulawski et al., 2021;

Wait & Stiehler, 2021). Amotivation is the influence of extrinsic or external factors

utterly independent of the individual, creating a lack of effort or desire (Grabowski et al.,

2021; Wait & Stiehler, 2021). The self-determination theory (SDT) argues that people are

motivated by activities they initiate and possess a strong psychological need to belong or

relatedness. SDT is grounded in a person's need for growth, which is the product of

competence, relatedness, and autonomy (Wait & Stiehler, 2021). Employees focus on the

outside or extrinsic factors anticipated outcomes and their ability to dictate and control

their positive results, defined as autonomy (Good et al., 2020; Wait & Stiehler, 2021). To

further this point, Wingrove et al. (2020) postulated that SDT and the fundamental

constructs of this theory were most appropriate for coaching supervision within coaching

ranks. SDT was identified as directly impacting a coach’s inherent growth tendencies and

regulated self-behaviors (Wingrove et al., 2020). Competence and relatedness are

produced when employees feel their decisions will influence a specific result or make a

difference. They identify and join others they trust and share common values (Good et

al., 2020; Wait & Stiehler, 2021). Good et al. (2020) hypothesized in their qualitative

findings, using self-determination theory as their conceptual framework, that when

salespeople determine they are making a difference, they experience the highest level of

motivation.

30

In contrast, Herzberg et al. (1959) would argue that Deci and Ryan’s (1985)

findings demonstrated extrinsic factors' influence on employee motivation. Still, those

outside factors are not experienced at their highest level without a counterbalance of

intrinsic factors. Therefore, Herzberg et al. concluded that extrinsic hygiene factors are

absent without an intrinsic motivating factor to produce an ideal environment for job

satisfaction.

Figure 6

Illustration of Deci and Ryan’s (1985) Self-determination Theory

Intrinsic Independent Variable: Opportunity for Advancement

Researchers identified intrinsic factors as motivators or high-level growth

constructs that promote job satisfaction. Herzberg et al. (1959) defined intrinsic

motivators as factors that contribute directly to an employee or employees' motivation.

Herzberg et al. identified several attributes that stimulate intrinsic motivation, such as (a)

achievement, (b) responsibility, (c) recognition, (d) work itself, (e) opportunity for

advancement, and (f) growth (Herzberg, 1974; Hur, 2018: Tan & Waheed, 2011).

Intrinsic Motivation and Self-

Determined Extrinsic Motivation

Satisfaction of

Psyhcological Needs

Autonomy

Competence

Relatedness

31

Intrinsic work motivation that is challenging and meaningful and offers an employee

recognition for accomplishments and opportunities for growth and advancement

influences an employee's satisfaction level (Barrick et al., 2015; Basinska & Dåderman,

2019), generating positive work attitudes that impact turnover intentions.

Opportunities for developmental career progression or advancement within an

organization are principal determinants of whether employees stay or leave (Carter &

Tourangeau, 2012; Crafts et al., 2018). Carter and Tourangeau (2012) supported these

findings in their research. The authors posited that the lack of inside opportunities for

advancement increased employee turnover versus the accessibility of ample

opportunities. Pediatric physicians further indicated in Crafts et al.'s (2018) study that the

perceived lack of opportunity for career advancement (p = <0.001) was a significant

influencer in pediatric physicians deciding to change their place of employment early in

their careers.

Personal growth and job satisfaction stem from the employee's desire for career

advancement opportunities (Lee et al., 2017; Lester, 2013). Tan and Waheed (2011)

posited that career advancement was essential to employees' life fulfillment goals and

was necessary to achieve job satisfaction. Parsa et al. (2014) concluded that career

advancement opportunities among academic employees positively correlated with work-

life quality. Lack of advancement opportunities increases turnover intentions and

eventually leads to elevated employee turnover, whereas increased opportunities for

advancement can positively influence commitment, reducing employee turnover levels

(Carter & Tourangeau, 2012; Crafts et al., 2018; Erasmus, 2020). Therefore, effective

32

dealership succession plans and promotion initiatives could slow turnover intentions and

eventual turnover.

Researchers present evidence that career advancement opportunities that motivate

employees to perform increase organizational commitment, job contentment, and job

satisfaction, reducing turnover intentions. Andrews and Mohammed (2020), in

conjunction with Xie et al. (2016), posited that career advancement opportunities directly

influenced employee job performance. However, employees who experience career

plateau experience decreased job satisfaction levels, and their preferences for turnover

increase (Andrews & Mohammed, 2020; Xie et al., 2016). Wang et al. (2016) suggested

that opportunities for advancement can bolster an employee's willingness to demonstrate

their advancement potential or merit, cultivating better performance.

Career advancement opportunities and promotability lessen turnover intentions

(Chan et al., 2016). However, in conjunction with management recognition of sales

performance, work-life balance and sales incentives proved to be primary motivators for

Indian retail salespeople (Prasad Kotni & Karumuri, 2018). Gunn et al. (2017)

demonstrated that opportunity for advancement was a prevailing theme in retail sales

management career profiles. Opportunities for advancement, earnings, and career paths

were vital contributors to the retail industry's negative career perception (Gunn et al.,

2017). Shaju and Subhashini's (2017) study of the automobile industry hypothesized that

extrinsic job factors, such as the opportunity for advancement, strongly correlated to job

satisfaction. This correlation was higher among those at the supervisory level. Additional

research shows that career management processes are designed to promote advancement

33

that reduces turnover intentions (de Oliveira et al., 2019). This relationship varied

depending on the amount of mediation from organizational management.

Extrinsic Independent Variable: Salary/Pay

In contrast to intrinsic satisfying motivators, researchers suggested that extrinsic

hygiene factors, such as pay/salary, are primarily lower-order environmental needs that

fulfill the basic requirements inherent to the job. Herzberg et al. (1959) theorized that in

conjunction with intrinsic job satisfaction factors, employees were affected by extrinsic

job factors that contributed to job dissatisfaction. Herzberg et al. identified salary/pay, or

compensation, as an extrinsic factor that adversely affects overall employee satisfaction.

Employee salary, sales force compensation, pay, or pay satisfaction is recognized as a

critical influencer of job satisfaction, performance, employee retention, motivation, and

turnover intentions (Call et al., 2015; Chan & Ao, 2019; Fatima, 2017; Tan & Waheed,

2011). Mburu (2017) opined that pay significantly influences work performance, and

organizations implementing strategies that promote compensation and advancement

experience decreased turnover and higher retention. Chan and Ao (2019) discovered that

highly paid casino employees were dissatisfied with their pay. Employees who expect

their jobs to pay well need additional pay incentives such as bonus packages. Božović et

al. (2019) concluded that human resource management practices that encompass

consistent compensation systems would positively increase banking employees' job

satisfaction levels. However, Chan and Ao revealed that dissatisfaction with pay did not

decrease employee commitment levels, indicating that well-thought-out pay plans can

seal between employee organizational commitments and decreased turnover intentions.

34

Pay incentives or rewards proved influential among salespersons and sales

managers if these pay programs are not perceived as methods to control behaviors

(Mallin & Pullins, 2009). Mallin and Pullins (2009) postulated that pay could be

detrimental to intrinsic motivation, and unattractive earning potential negatively impacts

job satisfaction and motivation. Holmberg et al. (2017) further posited that the

nonexistence of extrinsic factors adversely affects job satisfaction. Managed salary/pay

strategies help organizational managers attract, retain, and motivate employees to achieve

organizational goals and maintain competitive advantage (Arocas et al., 2019; Sarmad et

al., 2016). Therefore, dealership leaders could achieve collaborative effort and support by

designing and implementing pay structures that promote and fulfill higher-order needs.

Dealership managers who organizationally control extrinsic rewards can also

implement pay/salary initiatives that generate job satisfaction and lessens dissatisfaction

by offering rewards or incentives not based on monetary measures. Good et al. (2020)

discovered that intrinsic motivators were positively associated with increased salesperson

effort and that younger salespeople were not as motivated by the desire for money.

Therefore, it challenges managers and business owners to switch from outcome-based

monetary controls to more purpose-driven employment opportunities and initiatives.

Automobile salesperson compensation or pay is highly variable and depends on

individual dealership structure (Habel et al., 2021; Joetan & Kleiner, 2004). Most

salary/pay plans for automotive salespeople are commissions-based, highly competitive,

pressure-driven, and directly connected to a small percentage or commission of variable

profit generated from individual automobile and automobile product sales (Habel et al.,

35

2021; Joetan & Kleiner, 2004). This pay/salary system contributes to high job stress,

emotional exhaustion, low extrinsic job satisfaction, and high turnover among automotive

salespeople (Habel et al., 2021; Joetan & Kleiner, 2004). Hung et al. (2018) posited that

satisfaction with salary/pay structures generated elevated organizational commitment

levels, even in high-pressure operations, and turnover intentions remained low.

Researchers consistently demonstrated that pay/salary dissatisfaction negatively

correlated with turnover intention (Mohamed et al., 2017). Mohamed et al. (2017) tested

a hypothesis to examine if this relationship could be non-linear. The researchers

concluded that pay satisfaction and turnover intention shared a nonlinear relationship,

positing that pay dissatisfaction did not always increase employee turnover intentions

(Mohamed et al., 2017). Furthermore, Alshmemri et al. (2017) affirmed Herzberg et al.'s

(1959) position, concluding and further positing that reducing or eliminating concepts

that contribute to turnover or turnover intentions could improve the employee experience,