May 2020

Direct Primary Care: Evaluating a New

Model of Delivery and Financing

Health Care Cost Trends

2

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

Direct Primary Care: Evaluating a New

Model of Delivery and Financing

Caveat and Disclaimer

The opinions expressed and conclusions reached by the authors are their own and do not represent any official position or opinion of the Society of

Actuaries or its members. The Society of Actuaries makes no representation or warranty to the accuracy of the information.

This report was prepared by Milliman exclusively for the use or benefit of the Society of Actuaries for a specific and limited purpose. The report used data

from various sources, which Milliman has not audited. Any third party recipient of this report who desires professional guidance should not rely upon

Milliman’s report, but should engage qualified professionals for advice appropriate to its own specific needs.

Copyright © 2020 by the Society of Actuaries. All rights reserved.

AUTHORS

Fritz Busch, FSA, MAAA

Consulting Actuary

Milliman, Inc.

Dustin Grzeskowiak, FSA, MAAA

Consulting Actuary

Milliman, Inc.

SPONSORS

Society of Actuaries

Research Expanding Boundaries (REX)

Pool

Erik Huth, FSA, MAAA

Principal and Consulting Actuary

Milliman, Inc.

3

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

CONTENTS

1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 5

Literature Review ........................................................................................................................................................... 6

Market Survey ................................................................................................................................................................ 7

Case Study ...................................................................................................................................................................... 7

2. Background ........................................................................................................................................................... 9

Current State of Primary Care ....................................................................................................................................... 9

Milliman DPC Research ................................................................................................................................................ 10

3. Overview of DPC ................................................................................................................................................. 12

Definition and Common Features ............................................................................................................................... 12

Key Findings from Market Survey ............................................................................................................................... 14

4. Summary of DPC Literature Review ..................................................................................................................... 17

Overview ....................................................................................................................................................................... 17

Selection Criteria .......................................................................................................................................................... 17

Summary of Existing Literature ................................................................................................................................... 17

Overview of DPC.............................................................................................................................................. 18

Cost Outcomes ................................................................................................................................................ 19

Gaps in Existing DPC Research .................................................................................................................................... 22

5. Overview of Case Study....................................................................................................................................... 23

Study Structure ............................................................................................................................................................ 23

Study Goals ................................................................................................................................................................... 23

Data Description .......................................................................................................................................................... 24

Exposure Measures ......................................................................................................................................... 24

Cost Measures ................................................................................................................................................. 25

Benefit Coverages............................................................................................................................................ 25

6. Case Study Findings ............................................................................................................................................. 27

Population Differences ................................................................................................................................................ 27

Demographics .................................................................................................................................................. 27

Risk Selection and Morbidity ....................................................................................................................................... 28

Overall Demand for Health Care Services .................................................................................................................. 28

Emergency Department Visits ..................................................................................................................................... 31

Inpatient Hospital Admissions ..................................................................................................................................... 32

Total Employer Costs (DPC ROI) .................................................................................................................................. 32

7. Case Study Generalized Actuarial Framework for Funding Employer DPC Options .............................................. 36

Development of Estimated DPC FFS Claim Cost Savings ........................................................................................... 36

Overall DPC FFS Claim Cost Savings ............................................................................................................................ 41

Development of DPC Membership Fee Schedule ...................................................................................................... 41

Other Considerations for Employers Considering a DPC Option............................................................................... 43

8. Case Study Discussion and Limitations ................................................................................................................ 46

Discussion ..................................................................................................................................................................... 46

Limitations .................................................................................................................................................................... 47

Sample Size ...................................................................................................................................................... 47

Lack of Quality Measures ................................................................................................................................ 47

Variability in DPC ............................................................................................................................................. 48

Data Quality ..................................................................................................................................................... 48

DPC Practice Structure .................................................................................................................................... 49

Reliance 49

4

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

9. Case Study Data Sources ..................................................................................................................................... 50

Administrative Medical Claims .................................................................................................................................... 50

Administrative Prescription Drug Claims .................................................................................................................... 50

Health Plan Enrollment ................................................................................................................................................ 50

Benefit Plan Design ...................................................................................................................................................... 50

10. Case Study Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 52

Analytic Data Processing.............................................................................................................................................. 52

Milliman Health Cost Guidelines Grouper (HCG Grouper)............................................................................ 52

Milliman GlobalRVUs (GlobalRVUs) ................................................................................................................ 52

Milliman Advanced Risk Adjusters (MARA) .................................................................................................... 52

Actuarial Methodology ................................................................................................................................................ 52

Cohort Selection........................................................................................................................................................... 53

Metric Selection ........................................................................................................................................................... 54

Risk Adjuster ................................................................................................................................................................. 55

Statistical Analysis ........................................................................................................................................................ 56

11. Lessons Learned/Future Research ..................................................................................................................... 56

Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................................................. 57

Appendix A: Articles Included in Literature Review ................................................................................................. 58

Definitions of DPC ........................................................................................................................................................ 58

Overview of DPC .......................................................................................................................................................... 61

Cost Outcomes ............................................................................................................................................................. 68

Regulatory Considerations .......................................................................................................................................... 77

Provider Experience ..................................................................................................................................................... 81

Patient Access .............................................................................................................................................................. 83

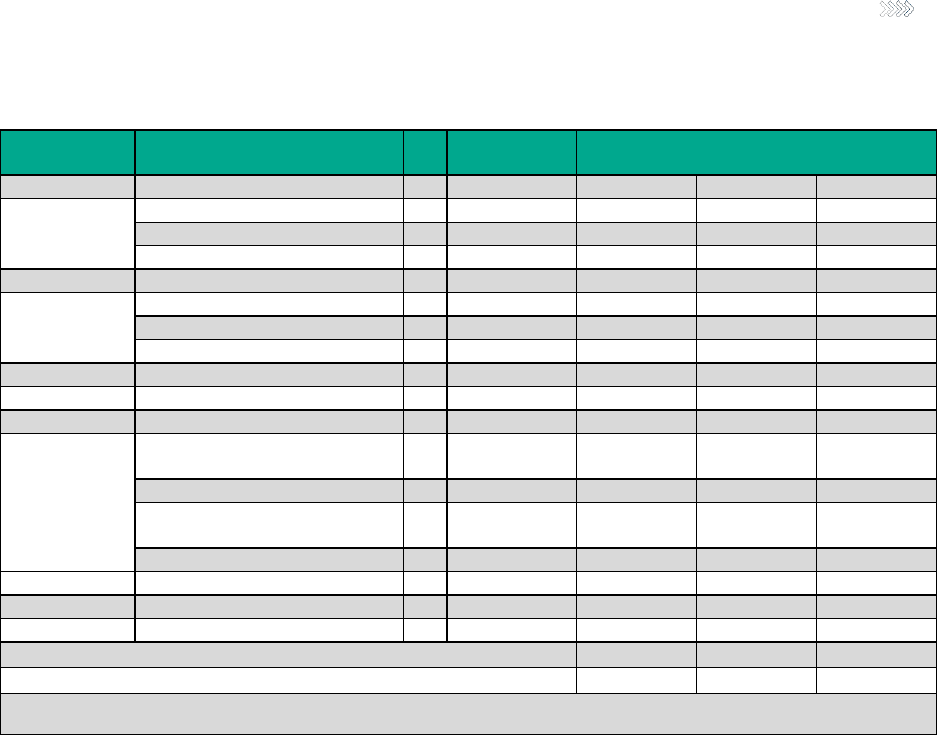

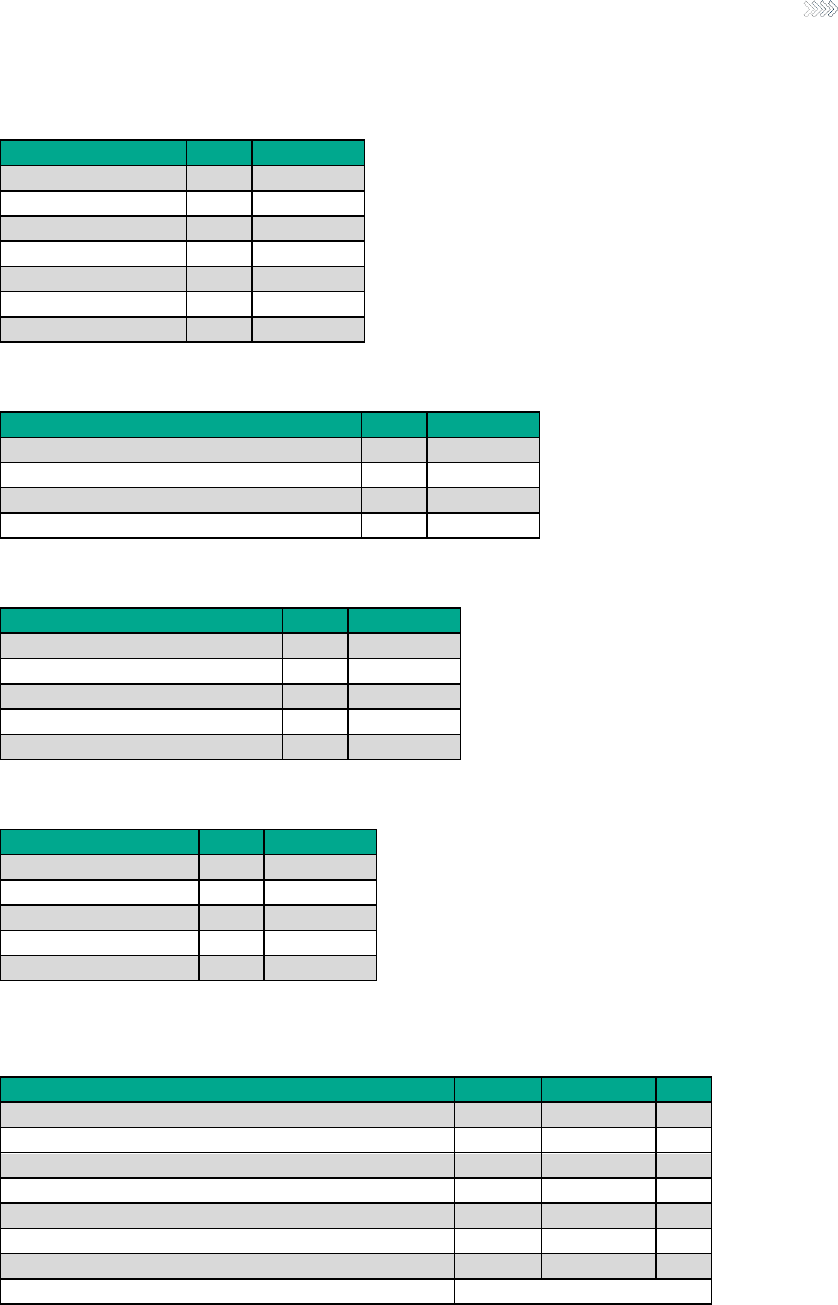

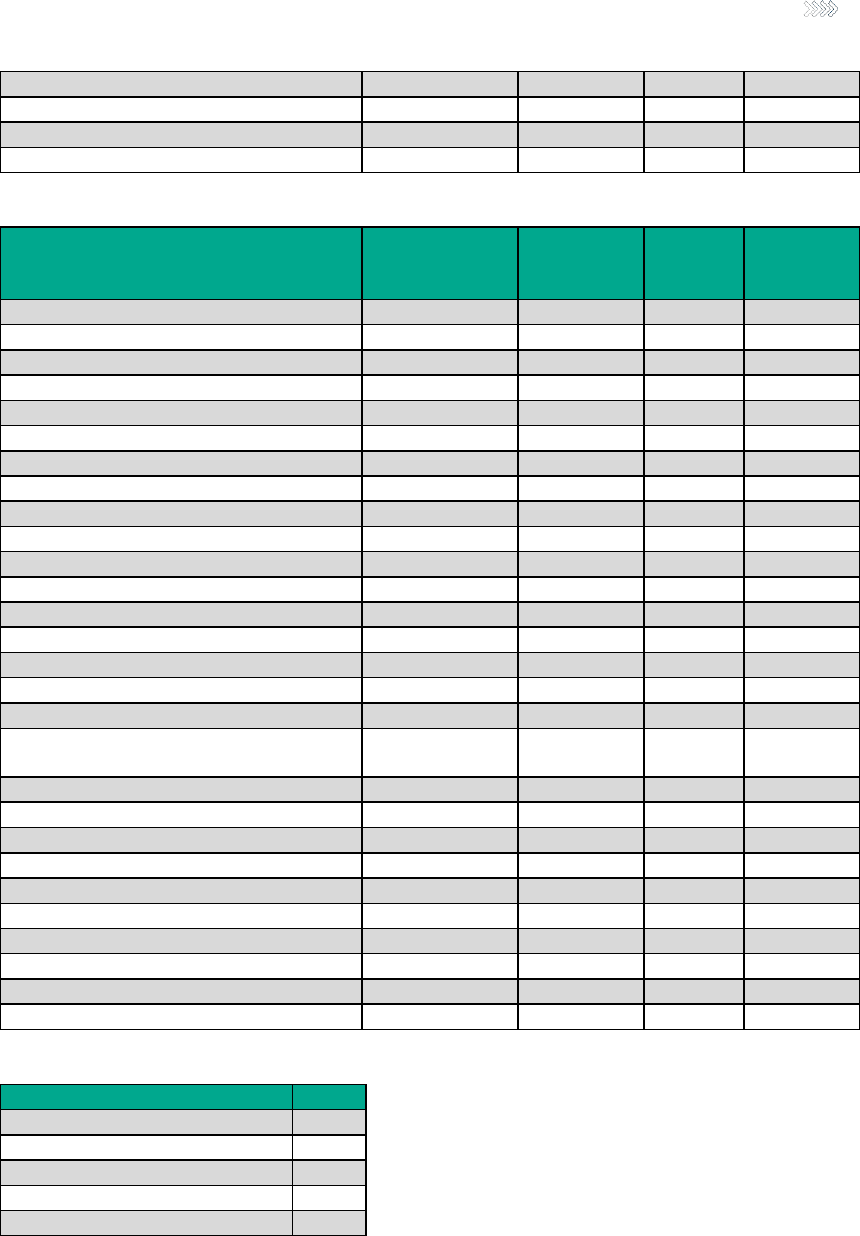

Appendix B: Full Market Survey Results .................................................................................................................. 86

Appendix C: Additional Development Detail for Milliman Advanced Risk Adjusters (MARA) ................................... 97

About the Society of Actuaries ................................................................................................................................ 98

5

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

Direct Primary Care: Evaluating a New Model

of Delivery and Financing

1. Executive Summary

Primary care is a vital and even foundational component of any health care system. Primary care physicians (PCPs)

are the front line of health care and are often the entry point for patients needing care. How often a patient accesses

primary care, and the quality of that care, can have significant impacts on downstream costs and patient health

outcomes. However, while PCPs are almost universally acknowledged as essential to achieving the health care Triple

Aim of providing high-quality care, at lower cost, with improved patient experience, many health care experts describe

the current state of primary care as being in crisis. This crisis is characterized by physician burnout, large PCP patient

panels, low pay for PCPs relative to other physician specialties, increased administrative burden, longer work hours

without increased reimbursement, an increased risk of mental health conditions and suicide, and ultimately a PCP

shortage relative to market demand.

Direct Primary Care (DPC) is an approach to delivering and financing primary care that attempts to respond to many

of these challenges. The DPC practice model is relatively new and still evolving, and there is no single accepted

definition of what constitutes a DPC practice. However, the most commonly used definition is as follows:

DPC physician practices are those that:

1. Charge patients a recurring—typically monthly—membership fee to cover most or all primary care-related

services.

2. Do not charge patients per-visit out-of-pocket amounts greater than the monthly equivalent of the retainer

fee.

3. Do not bill third parties on a fee-for-service (FFS) basis for services provided.

Other key features characterizing much of the DPC delivery model include:

• Contracting. DPC practices typically do not contract with insurers, government payers, or third-party

administrators (TPAs). DPC practices typically only contract directly with patients or with self-insured

employers.

• Recurring fee. The majority of DPC practice revenues typically come from monthly or annual DPC

membership fees, generally ranging from $40 to $85 per person per month.

• Smaller patient panels. DPC practices usually have fewer patients than traditional primary care practices,

typically fewer than 1,000 and most often around 200 to 600.

• Expanded patient access. Due primarily to smaller patient panels, members of a DPC practice have better

access to their PCP. This improved access manifests itself in longer-duration office visits, same-day or next-

day appointments, text or phone-based provider contact, and occasionally PCP home visits.

• Longer office visits. The typical length of an office visit for a traditional primary care practice is around 13 to

16 minutes. A significant portion of this time is typically not face time, because coding and documenting

electronic health records (EHRs) pressures keep physicians behind the computer screen. By contrast, for DPC

practices, office visits average around 40 minutes but can vary based on the patient’s need.

6

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

• Reduced patient cost sharing. Most DPC practices do not charge any cost sharing for services covered under

the DPC membership fee. Proponents of the model contend this improves care, because financial barriers

are often the cause of patients missing important follow-up visits.

The DPC financing and delivery model provides an alternative to traditional FFS-based primary care models, and

proponents of the DPC model claim that it greatly improves the patient-doctor relationship, reduces the

fragmentation of patient care, and improves both personal and professional satisfaction for physicians. Moreover,

DPC proponents also argue that this alternative primary care arrangement generates systemwide reductions in health

care utilization including hospitalization rates, emergency department usage, unnecessary radiology and diagnostic

tests, and specialist care, leading to broad-based health care cost savings.

Not surprisingly, DPC has its critics, who contend that any observed reductions in utilization or health care costs along

with membership in a DPC practice are either aberrant, based on small study sizes, or are driven by patient selection

(i.e., healthier patients choose DPCs and thus have lower costs than traditional patients). Critics also charge that the

model is not scalable to the public at large and exacerbates the physician shortages issue.

The Society of Actuaries (SOA) commissioned Milliman to develop this report to provide health care stakeholders—

patients, payers, policymakers and actuaries—with a comprehensive description of DPC as well as an objective

actuarial evaluation of certain claims made about the DPC model of care. We utilized three primary research

methodologies to develop this report: 1) a literature review, 2) a market survey of DPC practices, and 3) an

employer case study where we applied an actuarial methodology to evaluate certain cost and utilization outcomes

for patients enrolled in a DPC option. In addition to the formal methodologies presented in this paper, we also

conducted one-on-one interviews with 10 PCPs practicing under the DPC model to provide us with firsthand

background information and context for the key findings from our primary research methodologies.

Literature Review

Our literature review identified 36 relevant articles for our report and an additional seven sources providing definitions

of DPC. While the identified articles provided useful qualitative information relating to the DPC model of care, we

identified several quantitative gaps in the existing literature. Specifically, existing literature on DPC does not include

the following:

• A comprehensive survey of DPC practices to provide a landscape of the current DPC market

• A comparison of DPC patients versus non-DPC patients to determine characteristic differences between

patients choosing to enroll in DPC

• An actuarially adjusted comparison of cost, quality and utilization rates between patients enrolled in DPC and

patients who are not

• An actuarially adjusted return-on-investment (ROI) determination for an employer-based DPC program to

determine whether total FFS claim cost savings for enrolled patients offsets the cost of recurring DPC

membership fees

• A breakout of DPC results for chronically ill versus nonchronically ill patients

• A qualitative review of nondata-driven aspects of DPC such as provider engagement, patient engagement

and increased patient-provider face time

• A longitudinal study that measures whether DPC “bends the cost curve” in health care costs per patient over

time

7

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

Market Survey

Our DPC market survey was completed by about 200 DPC physicians, with most responding to all questions; we believe

that this sample size represents approximately 10% to 20% of all physicians currently practicing in a DPC setting.

Key findings from this survey included:

• The primary motivators for physicians choosing to operate a DPC practice were the “potential to provide

better primary care under a DPC model” (96%), “too little time for FFS visits” (85%), and “too much FFS

paperwork to complete” (78%). Just 10% of physicians indicated that the “potential to earn more under DPC”

was a primary motivator.

• The average per-person monthly DPC membership fees reported in the survey were $40 for children and

ranged from $65 to $85 for adults, depending on age. Most DPC practices do not charge a per-visit fee for

services covered under their DPC memberships (89%).

• The average reported current DPC patient panel size was 445, while the average target panel was 628. The

average ratio of the current to target DPC patient panel sizes was 70% (i.e., on average, the current DPC

patient panel was 30% below the target). For those DPC practices with a full DPC patient panel, the average

length of time to fill the panel was 21 months.

• Nearly all DPC physicians reported having better or much better “overall (personal and professional)

satisfaction” (99%), “ability to practice medicine” (98%), “quality of primary care” (98%), and “relationships

with their primary care patients” (97%) under a DPC model. Just 34% of DPC physicians reported having

better or much better “earnings as a PCP under a DPC model.”

• About 70% of respondents’ DPC practices were established in the last four years, indicating that the model

is growing in recognition and popularity but is still in its infancy.

Case Study

For our case study, we procured a longitudinal claims data set from an employer with a DPC option in its employee

health benefits plan. Members in the employer’s plan can elect to enroll in a traditional preferred provider

organization (PPO) style plan option, or they can choose to enroll in an option that includes a DPC membership, with

the employer covering the DPC membership fee. We applied various actuarial techniques in our evaluation of the

impact of the DPC option on cost and utilization.

We observed positive cost-related and utilization-related effects from the introduction of a DPC option in the

employer’s self-insured health benefits plan. About half of the members included in our analysis enrolled in the DPC

option, and the DPC option was associated with a statistically significant reduction in overall demand for health care

services (−12.64%) and emergency department usage (−40.51%) after controlling for differences in age, gender and

health status between the DPC and traditional cohorts. The DPC option was also associated with a lower inpatient

hospital admission rate (−19.90%), but the difference was not statistically significant due to the small number of

admissions during the two years analyzed. However, we also estimated that the introduction of a DPC option

increased total nonadministrative plan costs for the employer by 1.3% after consideration of the DPC membership

fee and other plan design changes for members enrolled in the DPC option.

We provided a generalized actuarial framework for funding employer DPC options. Our case study coupled with a

generalized actuarial framework show that implementing a DPC option may be financially viable for employers self-

insuring their health benefit plans but is heavily dependent on various employer-specific factors. Depending on three

factors—1) baseline level of claims costs in an employer’s plan; 2) how the DPC option is structured, including the

level of membership fees; and 3) the cost savings expected to be generated by the DPC delivery model—the

introduction of a DPC arrangement could be done on a cost-neutral basis or may potentially lead to overall cost savings

for the employer. The potential benefits to employers from the introduction of a DPC option may go beyond cost

8

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

considerations, however. A DPC option may give employees and dependents increased access to primary and urgent

care services, from the same provider at no cost, and may provide access to no-cost or low-cost basic labs and

prescription drugs as well. Employees may also have lower absenteeism rates, because DPC appointments can

generally be scheduled at almost any time and wait times at the office are usually shorter. Key challenges for

employers interested in offering a DPC option include the relatively limited number of DPC practices and the

geographic dispersion of employees and dependents.

9

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

2. Background

Current State of Primary Care

PCPs are often the entry point for patients needing care. How often a patient accesses primary care, and the quality

of that care, can have a significant impact on downstream costs and patient health outcomes.

1, 2

As clinicians, PCPs

are often treating illnesses, referring to specialists, prescribing medications or recommending diagnostic tests, just to

name a few responsibilities. Unlike specialists, who typically focus on specific body systems and related disease states,

PCPs routinely triage a variety of cases involving multiple body systems and overlapping symptoms. Moreover, PCPs

also often serve their patients in other more interpersonal roles, such as educator and trusted advisor, care

coordinator and health care system advocate. Optimally, a longitudinal and direct patient-physician relationship

should characterize primary care.

While almost universally acknowledged that PCPs are essential to achieving the health care Triple Aim of high-quality

care, lower cost and improved patient experience,

3

many PCPs and other health care experts describe the current

state of primary care as being in crisis.

4

This crisis is characterized by:

• Burnout. In their 2018 Journal of Internal Medicine article, C.P. West et al. define physician burnout as “a

work-related syndrome involving emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of reduced personal

accomplishment.”

5

We note in particular that West et al. define depersonalization as “feelings of treating

patients as objects rather than human beings and becoming more callous towards patients.”

6

A recent survey

from Medscape showed that nearly 50% of family medicine physicians report burnout.

7

This feature of

burnout is thought to be related to several factors further described below.

• Large patient panels. Most PCPs have in excess of 2,500 patients under their care; some argue that to provide

high-quality primary care, PCPs should care for fewer than 1,000 patients.

8

The large number of patients

cared for by most PCPs can lead to other downstream issues for patients related to access—including shorter

office visits, longer wait times, lower-quality primary care and, as noted above, physician burnout.

• Lower pay. A 2019 report by Medscape states that PCPs make about $100,000 less in salary per year than

the average specialist does.

9

1

Macinko, James, Barbara, Starfield, and Leiyu, Shi. 2007. Quantifying the Health Benefits of Primary Care Physician Supply in the

United States. International Journal of Health Services 37, no. 1:111–126.

2

Reschovsky, James D., Arkadipta, Ghosh, Kate, Stewart, and Deborah, Chollet. Paying More for Primary Care: Can It Help Bend

the Medicare Cost Curve? The Commonwealth Fund, March 2012,

https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_issue_brief_2012_mar_1585_r

eschovsky_paying_more_for_primary_care_finalv2.pdf (accessed February 6, 2020).

3

The Triple Aim does not have one single accepted definition, but it most often is defined by including some combination of

lowering costs, improving health quality and outcomes, and improving patient experience as well as health.

4

Schimpff, Stephen C. Why Primary Care Is in Crisis—and How to Fix It. Medical Economics, September 10, 2019,

https://www.medicaleconomics.com/news/why-primary-care-crisisand-how-fix-it (accessed February 6, 2020).

5

West, Colin, Liselotte, Dyrbye, and Tait, Shanafelt. 2018. Physician Burnout: Contributors, Consequences, and Solutions. Journal

of Internal Medicine 283, no. 1:516–529.

6

Ibid.

7

Kane, Leslie. Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression, and Suicide Report 2019. Medscape, January 16, 2019,

https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056?faf=1#3 (accessed February 6, 2020).

8

Schimpff, Stephen. How Many Patients Should a Primary Care Physician Care for? MedCity News, February 24, 2014,

https://medcitynews.com/2014/02/many-patients-primary-care-physician-care/ (accessed February 6, 2020).

9

Kane, Leslie. Medscape 2019 Physician Compensation Overview. Medscape, April 10, 2019,

https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#2 (accessed February 6, 2020).

10

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

• Increased administrative burden. EHRs were supposed to increase efficiency of health care delivery, but some

believe EHRs have not delivered on that promise.

10

Kaiser Health News reports, “Physicians complain about

clumsy, unintuitive systems and the number of hours spent clicking, typing, and trying to navigate them—

which is more than the hours they spend with patients.” Furthermore, the use of EHRs is associated with

greater rates of physician burnout.

11

Moreover, value-based care, which is intended in part to transition the financing of health care away from

FFS and toward compensating health care providers for delivery of high-quality and evidence-based care,

has thus far also brought with it additional and complex administrative burdens for physicians related to

documenting quality measures and other information needed to receive bonus payments or avoid penalties.

West et al. correlate physician payment models with higher burnout, “with physicians reporting purely

incentive- or performance-based incomes experience far higher burnout rates than salaried physicians.”

12

• Long work hours. Larger patient panels combined with increased administrative burden cause many

physicians, including PCPs, to work longer hours. Most of this additional work time is not reimbursable under

either Medicare or from private payers.

13

• Risk of suicide. Tragically, the combination of these conditions has put many physicians, including PCPs, at

risk of higher rates of mental health-related conditions and at higher risks of suicide.

14

• PCP shortages. Combined, it is not surprising that these trends are leading to fewer medical students entering

primary care and greater numbers of current PCPs ceasing to practice medicine.

15

At a time when there is a

greater need for more PCPs to meet rising demands caused by population growth, aging and increased

insurance coverage (which drives higher utilization of medical services), lower entry rates and higher attrition

rates will only further exacerbate the PCP shortage.

16, 17

It is in this context that a new movement among PCPs has emerged: DPC. While not necessarily formulated as a direct

response to the challenges listed above, DPC is nonetheless an approach to primary care delivery that appears to

address many of them. Its overall feasibility as a delivery model capitalizes on the core idea that primary care, due to

both its comparatively low cost (relative to other health care services) and predictability, may not need to be included

in major medical insurance nor administered by a third party. Rather, primary care can be packaged and distributed

directly to employers and consumers by PCPs themselves. This feature, along with what DPC advocates claim are the

advantages inherent within the DPC model, has motivated many physicians to switch from traditional care delivery

models to DPC, including new physicians straight out of medical school.

18

Milliman DPC Research

10

Schulte, Fred, and Erika, Fry. Death by 1,000 Clicks: Where Electronic Health Records Went Wrong. Fortune, March 18, 2019,

https://khn.org/news/death-by-a-thousand-clicks/ (accessed February 6, 2020).

11

Gardner, Rebekah, Emily, Cooper, Jacqueline, Haskell, Daniel A., Harris, Sara, Poplau, et al. 2019. Physician Stress and Burnout:

The Impact of Health Information Technology. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 26, no. 2:106–114.

12

West, Colin, Journal of Internal Medicine (see footnote 5).

13

Wright, Alexi, and Ingrid, Katz. 2018. Beyond Burnout – Redesigning Care to Restore Meaning and Sanity for Physicians. The New

England Journal of Medicine 378, no. 1:309–311.

14

Hampton, Tracy. 2005. Experts Address Risk of Physician Suicide. Journal of the American Medical Association 294, no. 10:

1189–1191.

15

AAMC. Physician Supply and Demand: A 15-Year Outlook: Key Findings. July 2019, https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-

07/workforce_projections-15-year_outlook_-key_findings.pdf (accessed on February 6, 2020).

16

Petterson, Stephen, Winston R., Liaw, Robert L., Phillips Jr, David L., Rabin, David S., Meyers, et al. 2012. Projecting US Primary

Care Physician Workforce Needs: 2010-2025. Annals of Family Medicine 10, no. 6:503–509.

17

AAFP. Significant Primary Care, Overall Physician Shortage Predicted by 2025. March 3, 2015,

https://www.aafp.org/news/practice-professional-issues/20150303aamcwkforce.html (accessed on February 6, 2020).

18

Author interviews with DPC physicians.

11

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

The SOA commissioned Milliman to develop this report to provide health care stakeholders—patients, payers,

policymakers and actuaries—with a comprehensive description of DPC as well as an objective actuarial evaluation of

certain claims made about the DPC model of care.

Our report utilized three primary research methodologies:

1. Literature Review. We conducted a literature review to identify and summarize any existing literature relating

to the DPC model of care or its efficacy. The purpose of this research method was to provide the reader with

a comprehensive overview of existing literature on this relatively new model. We also provide the reader

with a specific definition as to what constitutes a DPC practice. Ultimately, we identified 36 relevant articles

for our literature review and an additional seven sources providing definitions of DPC.

2. Market Survey. We conducted a market survey of DPC physicians to provide an overview of the current DPC

landscape. We conducted this survey in partnership with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP).

The survey was completed by about 200 DPC physicians, with most responding to all questions; we believe

that this sample size represents approximately 10–20% of all physicians currently practicing in a DPC setting.

The survey will provide the reader with an understanding of the current DPC landscape.

3. Employer Case Study. We conducted an actuarial-based evaluation of certain cost and utilization outcome

measures for patients enrolled in a DPC option. For this research, we procured a longitudinal claims data set

from an employer with a DPC option included in its health benefits plan for employees and dependents.

Members in the employer’s plan can elect to enroll in a traditional PPO-style plan option, or they can choose

to enroll in an option that includes a DPC membership, with the employer covering the membership fee.

About half of the members covered by the employer’s plan elected to enroll in the DPC option, and we

applied various actuarial techniques to evaluate the impact of the DPC option on their cost and utilization

measures.

Additionally, we conducted 10 one-on-one interviews with individual DPC physicians, each lasting at least one hour.

We guided these interviews with a short list of broad questions about each physician’s background, including their

experience with traditional primary care, their experience with DPC (and if applicable their transition from a traditional

primary care practice to a DPC practice), their motivations for operating a DPC practice, the impact of DPC on their

personal and professional satisfaction, the impact of DPC on their patients, and their views on the DPC model of care

broadly and where they see the movement trending. There is not a specific section of our report that summarizes

these interviews; rather, they helped to inform us as we conducted our research. Additionally, there are certain

instances in this report where we include information from these interviews as appropriate.

12

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

3. Overview of DPC

Definition and Common Features

The DPC practice model is relatively new and still evolving, and there appears to be no single accepted definition of

what constitutes a DPC practice. However, the most commonly used definition—based on our literature review—is

as follows:

DPC physician practices are those which:

1. Charge patients a recurring—typically monthly—membership fee to cover most or all primary care related

services.

2. Do not charge patients per-visit out-of-pocket amounts greater than the monthly equivalent of the retainer

fee.

3. Do not bill third parties on a FFS basis for services provided.

Even within this simple definition, there is a wide variety of DPC practice structures. However, based on our

experience, data collection from DPC physician surveys, and interviews with DPC physicians, the following features

are prominent among DPC practices:

• Contracting. DPC practices typically are not a part of insurer or TPA provider networks. Rather, DPC practices

typically only contract directly with patients or self-insured employers.

19

• Recurring fee. The majority of DPC practice revenues typically come from either a monthly or annual

membership fee that covers all services provided under the DPC arrangement. Reported monthly DPC

membership fees for adults generally range from $65 to $85.

20,21

Because DPC practices have lower

administrative overhead due to not contracting with TPAs (i.e., contracting, submitting claims), a larger

portion of the fee can go directly toward providing member care.

• Smaller patient panels. DPC practices usually have fewer patients than traditional primary care practices,

typically fewer than 1,000 and most often around 200 to 600.

22

• No third-party payments. DPC practices do not typically accept third-party payments from insurers or TPAs,

including Medicare and Medicaid, for services provided to their DPC patients.

• Expanded patient access. Because of smaller patient panels and reduced administrative tasks related to not

contracting with nor submitting claims to TPAs, DPC practices increase the amount of time PCPs can spend

providing patient care. In practice, this manifests itself in value-added aspects for DPC patients, such as

longer-duration office visits (discussed in more detail below), being able to schedule same-day or next-day

appointments, receive text or phone-based care, and occasionally have PCP home visits.

• Longer office visits. Smaller patient panels and reduced administrative overhead enable PCPs to spend more

time with each patient. The typical length of an office visit of a traditional primary care practice is around 13

19

Employers with self-insured health benefit plans are financially responsible for paying claims incurred by employees and

dependents enrolled in the plan. These employers typically retain traditional insurance carriers, such as Blue Cross Blue Shield, to

administer their health benefit plans, but the carriers in this instance only provide administrative services; the employer is liable

for all claim amounts. Fully insured employers on the other hand purchase group insurance products for their health benefit

plans where the employer pays fixed premium rates to a carrier and the carrier is financially responsible for paying claims

incurred by enrolled employees and dependents.

20

Huff, Charlotte. 2015. Direct Primary Care: Concierge Care for the Masses. Health Affairs 34, no. 12:2016–2019.

21

Rowe, Kyle, Whitney, Rowe, Josh, Umbehr, and Frank, Dong. 2017. Direct Primary Care in 2015: A Survey With Selected

Comparisons to 2005 Survey Data. Kansas Journal of Medicine 10, no. 1:3–6.

22

According to our DPC market survey.

13

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

to 16 minutes.

23

A significant portion of this time is typically not face time, because coding and EHR pressures

keep physicians behind the computer screen. By contrast, for DPC practices, it averages around 40 minutes

but can vary based on the patient’s need. For example, as noted above, PCPs are often dealing with disease

states related to multiple body systems, and providing high-quality patient care can be complex. Having

sufficient time with each patient to gather all relevant information, to thoroughly assess patient needs and

preferences, and to devise an appropriate care plan is of paramount importance.

• Reduced patient cost sharing. Most DPC practices do not charge any cost sharing for services covered under

the DPC membership fee. Proponents of the model contend this improves care, as financial barriers are often

the cause of patients missing important follow-up visits.

Covered services under a typical DPC arrangement include preventive care, basic illness treatment for both acute and

chronic conditions, and care coordination.

24

Many DPC physicians also arrange access for their DPC patients to other

discounted services such as prescription drugs, lab tests and imaging services. Patients from all segments of the health

insurance market—commercially insured, Medicare, Medicare Advantage, Medicaid and uninsured—can be and are

members of DPC practices.

25

Additionally, a number of employers have contracted with DPC practices to offer a DPC

option to employees and dependents through their self-insured group health benefit plans, where DPC membership

fees are covered by the employer for employees and dependents that choose to enroll.

Based on physician feedback gathered during our interviews, this financing and delivery model provides an alternative

to traditional FFS-based primary care models, which can be plagued by the challenges described above. The DPC

practice structure in many ways represents a patient-centered medical home (PCMH),

26

and proponents of the DPC

model claim that it greatly improves relationships with patients, reduces the fragmentation of patient care, reduces

costs and improves both personal and professional satisfaction of physicians. Moreover, the proponents argue that

this alternative primary care arrangement generates systemwide reductions in health care utilization, including

hospitalization rates, emergency department usage, unnecessary radiology and diagnostic tests, and specialist care.

Not surprisingly, DPC has its critics, who contend that these reductions are either aberrant, based on small study sizes,

or are driven by patient selection (i.e., healthier patients choose DPC and thus have lower costs than traditional

patients have). Critics also charge that the model is not scalable to the public at large and exacerbates the physician

shortage issue. It is beyond the scope of this paper to examine these criticisms and rebuttals in detail.

23

Wood, Debra. Average Time Doctors Spend With Patients: What’s the Number for Your Physician Specialty? Staff Care,

December 27, 2017, https://www.staffcare.com/physician-resources/which-physicians-spend-most-time-with-patients/ (accessed

February 6, 2020).

24

The Agency for Health care Research and Quality (AHRQ) notes that “Care Coordination in the primary care practice involves

deliberately organizing patient care activities and sharing information among all of the participants concerned with a patient’s

care to achieve safer and more effective care. The main goal of care coordination is to meet patients’ needs and preferences in

the delivery of high-quality, high-value health care.” See AHRQ. Care Coordination. August 2018,

https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/care/coordination.html (accessed February 6, 2020).

25

One notable exception to this is those enrolled in qualified HDHPs paired with HSAs. Due to current IRS rules, a DPC

membership is not allowed with a HDHP/HSA coverage combination. According to the Bipartisan Joint Committee on Taxation,

“Under present law, a direct primary care service arrangement is other coverage or insurance, and therefore the HDHP covered

person is not an eligible individual to contribute to an HSA.” See Joint Committee on Taxation. Description of H.R. 3708, The

“Primary Care Enhancement Act of 2019. October 23, 2019,

https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=download&id=5228&chk=5228&no_html=1 (accessed February 6, 2020).

26

The term “patient centered medical home,” at its core, is a concept. However, it is typically associated most closely with the

National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA)-accredited practice model. DPC practices are generally not NCQA-accredited

PCMHs.

14

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

Key Findings from Market Survey

We conducted a survey of DPC physicians, in partnership with the AAFP, to provide an overview of the current DPC

landscape. The survey was completed by more than 200 DPC physicians, which we believe represents approximately

10% to 20% of all physicians currently practicing in a DPC setting, based on our interviews with DPC stakeholders. The

survey will provide the reader with an understanding of the current DPC landscape.

We summarize the key findings from the survey below, and we provide the full survey results in Appendix B.

Overview of Survey Respondents

• Most reported practicing in a “pure DPC” practice (85%) and either having already opted out of Medicare

(75%) or being in the process of opting out of Medicare (5%).

o A “pure DPC” practice was defined as one that meets the three-pronged DPC practice definition

provided previously.

• The average respondent completed medical residency in 2002, with the first and third quartiles being 1997

and 2009, respectively. Most are MDs (83%) who specialize in family medicine (74%).

• Most worked independently to open their DPC practices (74%), are the sole owners of their DPC practices

(76%), and opened their practices after 2015 (71%).

• The primary motivators for choosing to operate a DPC practice were the “potential to provide better primary

care under a DPC model” (96%), “too little time for FFS visits” (85%), and “too much FFS paperwork to

complete” (78%). Just 10% indicated that the “potential to earn more under DPC” was a primary motivator.

• Most reported a willingness to participate in employer-based contracts for DPC services (67%); however,

those respondents contracting with employers reported that on average just 25% of their patient panels

were attributable to employer contracts.

• Most DPC practices are small, with 78% reporting DPC offices with either one or two physicians plus zero or

one nonmedical staff members.

DPC Membership Fees and Covered Services

• The average monthly DPC membership fees reported in the survey were as follows:

o Children: $40

o Adults ages 19–24: $65

o Adults ages 25–50: $75

o Adults ages 51–64: $80

o Adults ages 65 and over: $85

o Families: $150

• Most do not charge a per-visit fee for services covered under the membership by their DPC practices (89%),

and about half charge a one-time enrollment fee for new DPC memberships (54%).

• About two-thirds of respondents reported that their membership fees have not increased in the past three

years (62%), and the average increase during that period was reported to be about 1.5% per year. DPC

physicians responded that just 5% of members terminated their DPC memberships after one year.

• The majority of respondents reported covering the following procedures or services for no additional fees

with a DPC membership at their practices:

o Phone/text consults (99%)

o Same-day appointments (99%)

o EKG (88%)

o Telemedicine (88%)

o Urgent care/walk-in appointments (84%)

15

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

o Nutritional counseling (83%)

o Weight management (82%)

o Wellness coaching (79%)

o Biopsy and excisions (70%)

o Cryosurgery (65%)

o House calls/home visits (58%)

o Joint injections (58%)

o Spirometry (56%)

• The majority of respondents reported covering the following procedures or services for DPC members at

their practices with an additional fee (i.e., patient cost sharing):

o Basic laboratory testing such as HgbA1C, lipids, CMP, TSH, PSA, PAP, CBC, U/A (69%)

27

o Sending off pathology specimens (66%)

o Prescriptions drugs (57%)

o Adult immunizations (53%)

• The majority of respondents reported not covering the following procedures or services at their practices

(i.e., not included as part of a DPC membership nor offered for an additional patient fee):

o Flexible sigmoidoscopy exam (97%)

o Obstetrical services (91%)

o Vasectomy (88%)

o Colonoscopy (82%)

o Tympanometry (82%)

o Ultrasound imaging (74%)

o X-ray (74%)

o Addiction medicine (73%)

o Functional/integrative medicine (61%)

o Department of Transportation (DOT) physicals (57%)

o Endometrial sampling (57%)

o Children and adolescent immunizations (51%)

DPC Effects on Physician Experience

• The respondents reported an average current DPC patient panel of 445 and a target DPC patient panel of

628. The average ratio of the current to target DPC patient panel size was 70% (i.e., on average the current

DPC patient panel was 30% below the target size).

• For those respondents with full DPC patient panels, the average length of time to fill the panel was 21

months, with first and third quartiles of 10 and 24 months, respectively.

• Most respondents reported that each of the following has been better or much better under a DPC model

of care:

o Overall (personal and professional) satisfaction (99%)

o Ability to practice medicine (98%)

o Quality of primary care (98%)

o Relationships with primary care patients (97%)

o The amount of time spent on paperwork (88%)

o The amount of time spent at the office (73%)

• Just 34% of respondents reported having better or much better earnings as a PCP under a DPC model of care.

27

The tests listed are relatively common tests. HbA1C is for diabetes, lipids is for cholesterol, CMP measures metabolism, TSH is

for thyroid, PSA is for prostate, PAP is for cervical cancer, CBC is a complete blood count, and U/A is a urine analysis.

16

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

DPC Effects on Patient Experience

• On average, DPC members are able to schedule an appointment with their DPC provider within one day, wait

just four minutes in the DPC office for scheduled appointments to begin, and spend 38 minutes with the DPC

clinician during visits.

• Most DPC members are able to access their EHRs from their DPC practices through a patient portal (58%)

and are also able to sign up and manage their DPC enrollment using their DPC practice’s website (58%).

28

• Ninety-eight percent of respondents indicated that they expect the DPC model of care to:

o Improve patient satisfaction with primary care experience. (98%)

o Increase the extent to which patients rely on their PCPs to navigate the health system for

nonprimary care services (81%)

o Lower patient out-of-pocket costs for primary care services, including the DPC membership fee

(81%)

o Increase patient compliance with preventive care guidelines (68%)

28

It is important to note that DPC doctors generally do not use standard industry EHRs that are designed for purposes of

payment. DPC providers most often use EHRs that are designed solely for purposes of facilitating diagnosis, patient care and

efficiency, not payment.

17

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

4. Summary of DPC Literature Review

Overview

This section of our research report summarizes the key findings from our literature review relating to DPC. The

purpose of our literature review was twofold:

1. To gather descriptive information relating to the DPC model including definitions of DPC, distinctive

characteristics of DPC, common variations between DPC and traditional primary care practices, and

variations among DPC practices.

2. To summarize academic literature regarding the efficacy or expected efficacy (including cost, quality and

outcomes) of DPC and similarly structured primary care arrangements.

Selection Criteria

To identify DPC-related research articles to include in our report, we utilized the following resources:

• U.S. National Library of Medicine’s PubMed search engine

• Google Scholar search engine

• Google search engine

• Health Affairs

• Society of Actuaries Health Watch

• DPC Frontier’s summary of DPC-related academic and nonacademic articles

First, we gathered relevant articles from the above resources by conducting separate searches for “Direct Primary

Care,” “DPC,” “Concierge Medicine,” “Retainer Medicine” and “Subscription Medicine.” We also gathered additional

relevant articles by reviewing the citations for the gathered articles and identifying articles not found during our initial

searches. Next, we narrowed the initial broad list of articles to the more targeted list included in this report by

reviewing the article abstracts or introductions and retaining for our report only those articles that provide material

descriptive information on DPC or report on observed or theorized effects from the DPC model.

Ultimately, we identified 36 relevant articles for our literature review and an additional seven sources providing

definitions of DPC. It is possible—and in fact, it is even likely—that our search did not identify all relevant research

articles related to the DPC model; however, we believe that our search was adequate and that our report provides a

comprehensive overview of existing literature on the DPC model and its effects. We provide key excerpts from and

full reference information for each of the articles included in our literature review in Appendix A.

Summary of Existing Literature

For clarity, we have grouped the articles included in our literature review into the following categories:

1. Overview of DPC

2. Cost outcomes

3. Regulatory considerations

4. Provider experience

5. Patient access

18

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

In this section, we summarize some of the key results, common observations and expectations, and arguments in

favor of and against the DPC model of care from the articles included in our literature review. While this summary

provides readers with a valuable high-level overview of the articles we reviewed, it is not a substitute for reading the

articles themselves. Readers can find a listing of all of the articles included in our literature review in Appendix A, as

well as reference information for each article. Both this section and Appendix A group the articles into the five

categories listed above.

The summary points listed here are not necessarily attributable to any single article included in our literature review.

Rather, these summary points represent our best attempt to distill the information provided in all of the various

articles into a series of distinct and informative statements. In instances where many of the included articles provide

similar information, our summary points represent our best effort to combine these various similar pieces of

information. In instances where a single article provides a piece of unique and useful information, our summary points

may quote directly from an article.

Overview of DPC

• Physician dissatisfaction has increased during the past two decades, and some recent surveys show a

majority of physicians reporting some level of burnout. Physician burnout may be most acute for PCPs, who

are challenged by what some describe as low per-visit reimbursement, high malpractice insurance premiums,

overwhelming insurance paperwork, and the need to continue adding patients to their panels to support

their practices.

• DPC can provide an alternate practice structure for PCPs, with the potential to reduce their patient panel

sizes by two-thirds, increase time spent with each patient, and avoid burdensome insurance paperwork.

• DPC can provide an alternate primary care relationship for patients, with increased clinician access and the

potential to receive less fragmented care via establishing a long-term relationship with a PCP.

• DPC has similarities to another alternate model of primary care—concierge care—but a key differentiator is

that DPC practices have lower membership fees than concierge practices and do not also bill third parties on

a FFS basis for provided services as concierge practices typically do.

• Reported monthly DPC membership fees for adults range from $25 to $125 and generally cover preventive

care, vaccinations, basic illness treatment, care coordination, basic labs and access to discounted

prescriptions. DPC patients generally have 24/7 access to their clinicians via email or other electronic

communication mediums and can schedule same-day appointments during clinic hours. Patients from all

segments of the health insurance market—commercial insured, Medicare FFS, Medicare Advantage,

Medicaid and uninsured—are enrolled in DPC practices. Those enrolled in a DPC practice are generally

encouraged by their DPC clinicians to carry catastrophic health insurance in addition to their DPC

memberships.

• Proponents of the DPC model of care argue that this alternative primary care arrangement generates

systemwide reductions in health care utilization, including hospitalization rates, emergency department

usage, unnecessary radiology procedures and diagnostic tests, and specialist care.

• Critics of the DPC model of care contend that DPC is not a scalable primary care arrangement and that it

exacerbates the existing shortage of primary care clinicians in the U.S. by reducing patient panel sizes for

DPC practitioners.

• Proponents argue that reported outcomes show reduced overall health care costs for patients enrolled in

DPC clinics, while critics argue that these reported savings are due to patient selection (i.e., healthier patients

enroll in DPC practices and are then compared to less healthy patients to measure outcomes).

19

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

Cost Outcomes

Due to the relative newness of the DPC model of care, there is not an abundance of literature assessing cost outcomes

for DPC arrangements. However, from a clinical standpoint, DPC shares key characteristics with other models of

primary care, such as PCMHs, which are somewhat more established and for which additional literature exists.

According to the American College of Physicians, the PCMH is a care delivery model whereby patient treatment is

coordinated through a patient’s PCP with the goal of ensuring the patient receives the necessary care when and where

it is needed and in a manner the patient understands. The purported improved outcomes from the DPC model are

said to largely result from its patient-centered and high-touch delivery of primary care—a key differentiator for

PCMHs. Thus, in our literature review, we have included articles measuring outcomes for DPC, as well as key articles

measuring outcomes for the PCMH model of care. We believe this literature pertaining to PCMHs provides valuable

insights and considerations for evaluating the DPC model of care. The included articles relating to PCMHs are not

meant to represent a comprehensive literature review pertaining to PCMH cost outcomes. Rather, the included

articles are meant to provide useful data points for our review of the DPC model of care.

We also differentiate between outcomes-related articles that explicitly account for differences in population

demographics and health status and make use of appropriate methodologies in their analyses and those that do not.

We herein refer to articles accounting for patient differences in their methodologies as providing adjusted results,

that is, the results presented in these articles are adjusted for any differences in patient acuity when comparing cost

outcomes. The articles included in our literature review that present adjusted results applied various statistical

methodologies. In our summary points below, we do not distinguish between, nor evaluate, the various

methodologies used.

DPC Outcomes Articles

Adjusted Results

• We did not identify any articles that evaluated adjusted cost outcomes for models of care that meet our

specific definition of DPC.

• However, we did identify two articles presenting adjusted results for a model of care with at least one

important aspect similar to DPC, namely smaller patient panels. The company MDVIP uses the model. We

consider MDVIP’s model to represent concierge care rather than DPC. In addition to charging MDVIP

members an annual membership fee ranging from $1,650 to $2,200

29

($137 to $183 per month), which is

much higher than typical DPC membership fees, MDVIP also bills third-party payers for all services provided

to members. Even though the MDVIP model does not meet our definition of DPC, we believe these two

articles are relevant to our review of DPC because of the similarity of concierge care and DPC, as well as the

robust data sets and methodologies applied in these articles.

o Both articles showed lower inpatient hospital and emergency department utilization rates for

patients enrolled in concierge care compared to patients not enrolled in concierge care.

o One article showed lower overall health care claim costs for patients enrolled in concierge care

compared to patients not enrolled in concierge care. The other article did not show lower overall

health care claim costs for all patients analyzed but did show lower costs for older patients with

higher baseline claim costs.

o Neither article considered the annual membership fee for enrolling in concierge care in their

evaluations of whether enrollment in concierge care was associated with lower overall health care

claim costs.

29

MDVIP. The MDVIP Difference: More Than Just a Doctor, A Partner in Health. https://www.mdvip.com/patients/benefits

(accessed February 6, 2020).

20

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

Unadjusted Results

• We identified three articles that evaluated unadjusted cost outcomes for models of care meeting our specific

definition of DPC. Each article compared various cost and utilization measures for patients enrolled in DPC

to cost and utilization measures for patients not enrolled in DPC, without consideration for differences in

patient acuity or health status. These articles, therefore, do not discern between differences directly related

to DPC versus differences caused by other factors unrelated to DPC, such as age, gender, health status,

geography, etc. We also identified additional articles reporting unadjusted results for DPC that we did not

include in our literature review because they were not source articles; rather, these additional articles were

reporting various figures from the three source articles already included.

o All three articles showed lower overall health care claim costs for patients enrolled in DPC compared

to patients not enrolled in DPC, without consideration for the DPC membership fees.

o One of the articles showed lower overall health care claim costs for patients enrolled in DPC

compared to patients not enrolled in DPC after consideration of the DPC membership fee; the other

two articles did not evaluate the level of the DPC membership fees relative to the lower claim costs.

o One of the articles showed lower inpatient hospital and emergency department utilization rates for

patients enrolled in DPC compared to patients not enrolled in DPC. The other two articles did not

evaluate these measures.

Articles on PCMH Outcomes

Adjusted Results

• Ghany et al. (2018) showed that Medicare Advantage patients enrolled in PCMHs had lower inpatient

hospital utilization rates and overall health care claim costs compared to patients not enrolled in PCMHs.

• David et al. (2015) showed that Medicaid patients enrolled in PCMHs did not show lower overall total health

care claim costs compared to patients not enrolled in PCMHs.

• Rosenthal et al. (2015) showed that commercially insured patients enrolled in PCMHs had lower emergency

department utilization rates and higher quality of care scores compared to patients not enrolled in PCMHs.

They also showed that certain results, such as the lower relative overall health care claim costs, were more

pronounced among PCMH patients with multiple comorbidities.

• Neal et al. (2015) showed that chronically ill commercial patients enrolled in PCMHs showed lower overall

health care claim costs, as well as lower utilization rates for inpatient hospital and physician specialist

services, compared to patients not enrolled in PCMHs.

• Friedberg et al. (2014) showed that chronically ill commercial patients enrolled in PCMHs showed lower

emergency department utilization rates compared to patients not enrolled in PCMHs. They also showed that

nonchronically ill commercial patients enrolled in PCMHs did not show lower emergency department

utilization rates compared to patients not enrolled in PCMHs.

• Meyers et al. (2019) showed that chronically ill patients enrolled in high-touch team-based models of primary

care showed lower inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, emergency department and ambulatory care-

sensitive encounter utilization rates compared to patients not enrolled in high-touch team-based models of

primary care. They also showed that, under this model of care, nonchronically ill patients actually showed

higher utilization rates.

21

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

Regulatory Considerations

At the federal level

• The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) permits qualified health plans (QHPs) sold through the

ACA insurance exchanges to provide coverage through DPCs paired with wraparound insurance. No QHPs

have offered such a product to our knowledge.

• The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) prohibits individuals with health savings accounts (HSAs) paired with high-

deductible health plans (HDHPs) from having an agreement with a DPC provider.

• Various federal bills have been proposed that would permit patients with HSAs paired with HDHPs to not

only have agreements with a DPC provider but to use their HSAs to pay for DPC membership fees.

At the state level

• Certain consumer advocates and insurance commissioners have raised concerns as to whether DPC practices

are involved in “the business of insurance.”

• Some states have passed laws clarifying that DPC is outside of the business of insurance and constitutes a

medical service.

• Some states, such as Maryland, have recommended that DPC practices include certain contractual provisions

in member agreements to avoid being considered as involved in "the business of insurance.” These

recommended contractual provisions included:

o Limiting provided services under the DPC agreement to an annual physical, follow-up care relating

to the physical, and a specific number of other visits.

o Establishing the DPC membership fee by determining the market value of the expected services

provided under the agreement.

o Specifying the covered services under the DPC agreement with as much clarity as possible.

o Allowing patients to terminate their DPC agreements for any reason, at any time, and to receive

prorated reimbursements of any DPC membership fees already paid.

o Placing a cap on the number of patients with whom a DPC practice may enter into agreements.

Provider Experience

• Many DPC physicians claim that by not billing third parties on a FFS basis for provided services and by limiting

the size of their patient panels, they have more time to provide patient care.

• Some DPC practices have proved viable and sustainable from a financial standpoint, with patient panels

about one-third the size of traditional primary care patient panels and significantly reduced practice

overhead costs.

• Legal and ethical concerns have been raised about patient continuity of care when an existing nonretainer-

based primary care practice transitions to a retainer-based practice.

Patient Access

• DPC presents a theoretically sound model for improving the attributes of primary care for enrolled patients,

such as first contact care and long-term improved treatment.

• At a health system level, DPC theoretically improves access to health care for enrolled patients while reducing

access to health care for nonenrolled patients by reducing the number of nonretainer-based PCPs who would

otherwise have larger patient panels.

• Patients often do not have the analytic framework or information necessary to evaluate whether to remain

with their primary care clinicians during a transition to DPC.

22

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

• There is increased demand by health care patients for patient-centric solutions, and DPC may provide one

way of fulfilling this demand.

• DPC may run counter to the primary mission and goal of most health care payment and delivery reforms,

which are focused on expanding overall access to health care rather than increasing access for some patients

while decreasing access for other patients via reduced primary care panel sizes.

• Surveys of retainer-based primary care practices, including DPC and concierge style, have shown lower

prevalence of African American, Hispanic and Medicaid patients enrolled in retainer-based practices than

nonretainer counterparts.

Gaps in Existing DPC Research

The DPC model of care is relatively new and still evolving, and as such, the body of existing literature relating to this

model of care is somewhat limited. Stakeholders evaluating the efficacy and sustainability of this primary care

arrangement would benefit from the following research initiatives:

• A comprehensive survey of DPC practices including geographic information, services provided, membership

fee amounts and structures, motivation and resources for practicing under a DPC model, and information

related to provider and patient satisfaction. We believe that our market survey provided in Section 3

addresses this research gap.

• A comprehensive comparison of DPC patients versus non-DPC patients, particularly in a patient-choice

setting, to determine characteristic differences between patients choosing to enroll in DPC versus those who

are not choosing to enroll in DPC (e.g., DPC patients are younger, healthier and have more children). We

believe that our case study introduced in Section 5 addresses this research gap.

• An actuarially adjusted comparison of cost, quality and utilization rates between patients who are enrolled

in DPC and patients who are not. We believe that our case study introduced in Section 5 addresses this

research gap with respect to certain cost and utilization measures.

• An actuarially adjusted ROI determination for employers contracting with DPC practices on behalf of

employees to determine whether overall total health care claim cost savings for enrolled patients offset the

cost of recurring DPC membership fees. We believe that our case study introduced in Section 5 addresses

this research gap.

• A breakout of DPC results for chronically ill versus nonchronically ill patients. Similarly, structured primary

care arrangements have shown the most positive benefits for chronically ill patients, and preliminary

evidence indicates that DPC tends to attract healthier patients under an employer-arranged DPC offering. It

would be prudent for DPC practitioners to learn whether chronically ill patients are most likely to benefit

from the DPC model of care but also least likely to enroll. Our research does not address this gap due to data

limitations.

• A qualitative review of nondata-driven aspects of DPC, such as provider engagement, patient engagement,

increased patient-provider face time. Our research does not address this gap due to data limitations.

• A longitudinal study that measure whether DPC “bends the cost curve” in health care claim costs per patient

and whether any potential reduction in claim costs due to DPC only represents a one-time level shift in cost.

Our research does not address this gap due to data limitations.

23

Copyright © 2020 Society of Actuaries

5. Overview of Case Study

Because the DPC model is new, evolving and lacks consensus as to its efficacy, it will be necessary going forward to

accurately assess the impacts of the model on key features of the health care system, especially those related to the

Triple Aim goals of cost, quality and patient experience. If credible, quantitative data support the model’s net

advantages over the dominant conventional primary care model, all constituents stand to benefit, including

employers, policymakers, health plans and the general public. More quantitative information related to any favorable

impacts of DPC is, therefore, critical. Likewise, studies could also show weaknesses in the model that need to be

addressed, which may help the DPC movement evolve in a way that leads to the greatest overall public good.

Study Structure

Our study uses actual data of meaningful sample size,

30

combined with actuarial adjustments and analysis, to begin

quantifying the potential impacts of the DPC model relative to a traditional primary care model. As would be expected

for most studies of this nature, there are a number of potentially confounding variables that may obscure or distort

the true effect of the DPC model. Thus, our study design seeks to minimize any potential impacts of these confounding

variables through two key structural features:

• A quasi-control group: As we detail later in this paper, our data is derived from a single employer that offers

a DPC benefit option and a traditional benefit option. This arrangement will, as much as practically possible,

increase the likelihood that the cohorts of individuals in each option (DPC and traditional) are similar

demographically, particularly with regard to features other than age, gender and health status (which are

accounted for with other adjustments). For example, differences in expected claim costs due to working in

different industries do not influence study outcomes, because the data come from a single employer. Many

enrollees also share similar geographic regions and also likely utilize many of the same health care facility-

based providers such as hospitals, thus health care cost variations due to geography are also minimized.

Note that this is not a control group in the strictest sense, because that would entail various aspects of