’

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’s

’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

P

LANNER’S GUID

E

Programs Work

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

Making

Health

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

Communication

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES

G

APuide

National Institutes of Health

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlan

’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

National Cancer Institute

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner

G

uideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

Making

Health

Communication

Programs Work

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES

Public Health Service • National Institutes of Health

National Cancer Institute

Guide PlannersGuide PlannersGuide PlannersGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

Preface

T

his book is a revision of the original Making Health

Communication Programs Work, first printed in 1989, which

the Office of Cancer Communications (OCC, now the Office

of Communications) of the National Cancer Institute (NCI)

developed to guide communication program planning. During the 25

years that NCI has been involved in health communication, ongoing

evaluation of our communication programs has affirmed the value of

using specific communication strategies to promote health and prevent

disease. Research and practice continue to expand our understanding

of the principles, theories, and techniques that provide a sound

foundation for successful health communication programs. The purpose

of this revision is to update communication planning guidelines to

account for the advances in knowledge and technology that have

occurred during the past decade.

To prepare this update, NCI solicited ideas and information from

various health communication program planners and experts (see

Acknowledgments). Their contributions ranged from reviewing and

commenting on existing text to providing real-life examples to illustrate

key concepts. In addition, the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) provided extensive input as part of the agency’s

partnership with NCI.

Although communicating effectively about health is an exacting task,

those who have the earlier version of this publication know that it is

possible. We hope the ideas and information in this revision will help

new health communication programs start soundly and mature

programs work even better.

Acknowledgments

Many health communication experts contributed to the revision of this book.

For their invaluable input, we would like to thank:

Elaine Bratic Arkin

Health Communications Consultant

Cynthia Bauer, Ph.D.

U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services

John Burklow

Office of Communication and Public Liaison

National Institutes of Health

Lynne Doner

Health Communications Consultant

Timothy Edgar, Ph.D.

Westat

Brian R. Flay

University of Illinois at Chicago

Vicki S. Freimuth, Ph.D.

Office of Communication

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Joanne Gallivan, M.S., R.D.

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive

and Kidney Diseases

Karen Glanz, Ph.D., M.P.H.

Cancer Research Center of Hawaii

Bernard Glassman, M.A.T.

Special Expert in Informatics

National Cancer Institute

Susan Hager

Hager Sharp

Jane Lewis, Dr.P.H.

UMDNJ, School of Public Health

Terry Long

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Kathleen Loughrey, M.S., R.D. Health Communications Consultant

Susan K. Maloney, M.H.S. Health Communications Consultant

Joy R. Mara, M.A.

Joy R. Mara Communications

John McGrath

National Institute of Child Health and

Human Development

Diane Miller, M.P.A.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and

Alcoholism

Ken Rabin, Ph.D.

Ruder Finn Healthcare, Inc.

Scott C. Ratzan, M.D., M.P.A.

Journal of Health Communication

U.S. Agency for International Development

Barbara K. Rimer, Dr.P.H.

Division of Cancer Control and

Population Sciences

National Cancer Institute

Victor J. Strecher, Ph.D., M.P.H.

University of Michigan

Tim L. Tinker, Dr.P.H., M.P.H.

Widmeyer Communications

We would especially like to thank Elaine Bratic Arkin, author of the original book, whose knowledge of

health communication program planning made this revision possible, as well as Lynne Doner, whose

broad-based consumer research and evaluation expertise has enhanced the book’s content and quality.

Both have provided hours of review and consultation, and we are grateful to them for their contributions.

Thanks to the staff of the Office of Communications, particularly Nelvis Castro, Ellen Eisner, and Anne

Lubenow. And thanks to Christine Theisen, who coordinated the revisions to the original text.

This document was revised in coordination with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention during

development of CDCynergy—a program-planning tool on CD-ROM.

Table of Contents

Why Should You Use This Book?

i

Introduction

1

The Role of Health Communication in Disease Prevention and Control

2

What Health Communication Can and Cannot Do

3

Planning Frameworks, Theories, and Models of Change

7

How Market Research and Evaluation Fit Into Communication Programs

8

Selected Readings

9

Overview: The Health Communication Process

11

The Stages of the Health Communication Process

11

Stage 1: Planning and Strategy Development

15

Why Planning Is Important

16

Planning Steps

16

Common Myths and Misconceptions About Planning

48

Selected Readings

50

Stage 2: Developing and Pretesting Concepts,

53

Messages, and Materials

Why Developing and Pretesting Messages and Materials Are Important

54

Steps in Developing and Pretesting Messages and Materials

54

Planning for Production, Distribution, Promotion, and Process Evaluation

86

Common Myths and Misconceptions About Materials Pretesting

86

Selected Readings

87

Stage 3: Implementing the Program

91

Preparing to Implement Your Program

92

Maintaining Media Relations After Launch

95

Working With the Media During a Crisis Situation

98

Managing Implementation: Monitoring and Problem Solving

98

Maintaining Partnerships

102

Common Myths and Misconceptions About Program Implementation

103

Selected Readings

104

Stage 4: Assessing Effectiveness and

107

Making Refinements

Why Outcome Evaluation Is Important

108

Revising the Outcome Evaluation Plan

108

Conducting Outcome Evaluation

110

Refining Your Health Communication Program

121

Common Myths and Misconceptions About Evaluation

121

Selected Readings

123

Communication Research Methods

125

Types of Communication Research

126

Differences Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methods

126

Qualitative Research Methods

127

Quasi-Quantitative Research Methods: Pretesting Messages and Materials

141

Quantitative Research Methods

157

Additional Research Methods

161

Appendix A: Communication Planning

169

Forms and Samples

Appendix B: Selected Planning Frameworks, Social

217

Science Theories, and Models of Change

Appendix C: Information Sources

229

Appendix D: Selected Readings and Resources

235

Appendix E: Glossary

245

Guide PlannersGuide PlannersGuide PlannersGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

Why Should You Use This Book?

T

he planning steps in this book can help make any

communication program work, regardless of size, topic,

geographic span, intended audience, or budget. (intended

audience is the term this book uses to convey what other

publications may refer to as a target audience.) The key is reading all

the steps and adapting those relevant to your program at a level of

effort appropriate to the program’s scope. The tips and sidebars

throughout the book suggest ways to tailor the process to your

various communication needs.

If you have limited funding, you might

• Work with partners who can add their resources to your own

• Conduct activities on a smaller scale

• Use volunteer assistance

• Seek out existing information and approaches developed by

programs that have addressed similar issues to reduce

developmental costs

Don’t let budget constraints keep you from setting objectives, learning

about your intended audience, or pretesting. Neglecting any of these

steps could limit your program’s effectiveness before it starts.

This book describes a practical approach for planning and

implementing health communication efforts; it offers guidelines, not

hard and fast rules.Your situation may not permit or require each step

outlined in the following chapters, but we hope you will consider each

guideline and decide carefully whether it applies to your situation.

To request additional copies of this book, please visit NCI’s Web site

at

www.cancer.gov or call NCI’s Cancer Information Service at

1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

INTRODUCTION

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

INTRO

Introduction

In This Section:

• The role of health communication in disease prevention and control

• What health communication can and cannot do

• Planning frameworks, theories, and models of change

• How research and evaluation fit into communication programs

Questions to Ask and Answer:

• Can communication help us achieve all or some of our aims?

• How can health communication fit into our program?

• What theories, models, and practices should we use to plan

our communication program?

• What types of evaluation should we include?

The Role of Health Communication in

Disease Prevention and Control

There are numerous definitions of health

communication. The National Cancer

Institute and the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention use the following:

The study and use of communication

strategies to inform and influence

individual and community decisions

that enhance health.

Use the principles of effective health

communication to plan and create initiatives

at all levels, from one brochure or Web site

to a complete communication campaign.

Successful health communication programs

involve more than the production of

messages and materials. They use

research-based strategies to shape the

products and determine the channels that

deliver them to the right intended audiences.

Since this book first appeared in 1989,

the discipline of health communication has

grown and matured. As research has

continued to validate and define the

effectiveness of health communication, this

book has become a widely accepted tool

for promoting public health. Healthy People

2010, the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services’ stated health objectives for

the nation, contains separate objectives for

health communication for the first time.

Meanwhile, the availability of new

technologies is expanding access to

health information and raising questions

about equality of access, accuracy of

information, and how to use the new tools

most effectively.

2

INTRO

What Health Communication Can

and Cannot Do

Understanding what health communication

can and cannot do is critical to

communicating successfully. Health

communication is one tool for promoting or

improving health. Changes in health care

services, technology, regulations, and policy

are often also necessary to completely

address a health problem.

Communication alone can:

• Increase the intended audience’s

knowledge and awareness of a health

issue, problem, or solution

• Influence perceptions, beliefs, and

attitudes that may change social norms

• Prompt action

• Demonstrate or illustrate healthy skills

• Reinforce knowledge, attitudes,

or behavior

• Show the benefit of behavior change

• Advocate a position on a health issue

or policy

• Increase demand or support for

health services

• Refute myths and misconceptions

• Strengthen organizational relationships

Communication combined with other

strategies can:

• Cause sustained change in which an

individual adopts and maintains a new

health behavior or an organization adopts

and maintains a new policy direction

• Overcome barriers/systemic problems,

such as insufficient access to care

Communication cannot:

• Compensate for inadequate health care or

access to health care services

• Produce sustained change in complex

health behaviors without the support of a

larger program for change, including

components addressing health care

services, technology, and changes in

regulations and policy

• Be equally effective in addressing all

issues or relaying all messages because

the topic or suggested behavior change

may be complex, because the intended

audience may have preconceptions about

the topic or message sender, or because

the topic may be controversial

Communication Can Affect Multiple

Types of Change

Health communication programs can

affect change among individuals and also

in organizations, communities, and society

as a whole:

• Individuals—The interpersonal level is the

most fundamental level of health-related

communication because individual

behavior affects health status.

Communication can affect individuals’

awareness, knowledge, attitudes, self-

efficacy, skills, and commitment to

behavior change. Activities directed at

other intended audiences for change may

also affect individual change, such as

involving patients in their own care.

• Groups—The informal groups to which

people belong and the community settings

they frequent can have a significant

impact on their health. Examples include

relationships between customers and

employees at a salon or restaurant,

exercisers who go to the same gym,

students and parents in a school setting,

employees at a worksite, and patients and

health professionals at a clinic. Activities

aimed at this level can take advantage of

these informal settings.

Making Health Communication Programs Work

3

• Organizations—Organizations are groups

with defined structures, such as

associations, clubs, or civic groups. This

category can also include businesses,

government agencies, and health insurers.

Organizations can carry health messages

to their constituents, provide support for

health communication programs, and

make policy changes that encourage

individual change.

• Communities—Community opinion

leaders and policymakers can be effective

allies in influencing change in policies,

products, and services that can hinder or

support people’s actions. By influencing

communities, health communication

programs can promote increased

awareness of an issue, changes in

attitudes and beliefs, and group or

institutional support for desirable

behaviors. In addition, communication

can advocate policy or structural changes

in the community (e.g., sidewalks) that

encourage healthy behavior.

• Society—Society as a whole influences

individual behavior by affecting norms and

values, attitudes and opinions, laws and

policies, and by creating physical,

economic, cultural, and information

environments. Health communication

programs aimed at the societal level can

change individual attitudes or behavior

and thus change social norms. Efforts

to reduce drunk driving, for example,

have changed individual and societal

attitudes, behaviors, and policies through

multiple forms of intervention,

including communication.

Multistrategy health communication

programs can address one or all of

the above.

Communication Programs Can Include

Multiple Methods of Influence

Health communicators can use a wide range

of methods to design programs to

fit specific circumstances. These

methods include:

• Media literacy—teaches intended

audiences (often youth) to deconstruct

media messages so they can identify the

sponsor’s motives; also teaches

communicators how to compose

messages attuned to the intended

audience’s point of view

• Media advocacy—seeks to change the

social and political environment in which

decisions that affect health and health

resources are made by influencing the

mass media’s selection of topics and by

shaping the debate about those topics

• Public relations—promotes the inclusion

of messages about a health issue or

behavior in the mass media

• Advertising—places paid or public service

messages in the media or in public spaces

to increase awareness of and support for

a product, service, or behavior

• Education entertainment—seeks to

embed health-promoting messages and

storylines into entertainment and news

programs or to eliminate messages that

counter health messages; can also include

seeking entertainment industry support for

a health issue

• Individual and group instruction—

influences, counsels, and provides skills to

support desirable behaviors

• Partnership development—increases

support for a program or issue by

harnessing the influence, credibility, and

resources of profit, nonprofit, or

governmental organizations

4

Introduction

INTRO

CHARACTERISTICS OF EFFECTIVE HEALTH COMMUNICATION CAMPAIGNS

Certain attributes can make health communication campaigns more effective.

Use the guidelines in this section to plan your campaign.

Define the communication campaign goal effectively:

• Identify the larger goal

• Determine which part of the larger goal could be met by a communication campaign

• Describe the specific objectives of the campaign; integrate these into a campaign plan

Define the intended audience effectively:

• Identify the group to whom you want to communicate your message

• Consider identifying subgroups to whom you could tailor your message

• Learn as much as possible about the intended audience; add information about beliefs,

current actions, and social and physical environment to demographic information

Create messages effectively:

• Brainstorm messages that fit with the communication campaign goal and the

intended audience(s)

• Identify channels and sources that are considered credible and influential by the

intended audience(s)

• Consider the best times to reach the audience(s) and prepare messages accordingly

• Select a few messages and plan to pretest them

Pretest and revise messages and materials effectively:

• Select pretesting methods that fit the campaign’s budget and timeline

• Pretest messages and materials with people who share the attributes of the

intended audience(s)

• Take the time to revise messages and materials based upon pretesting findings

Implement the campaign effectively:

• Follow the plans you developed at the beginning of the campaign

• Communicate with partners and the media as necessary to ensure the campaign

runs smoothly

• Begin evaluating the campaign plan and processes as soon as the campaign

is implemented

Note. Adapted from the University of Kansas Community Toolbox, Community

Workstation, available at

http://ctb.lsi.ukans.edu/tools/CWS/socialmarketing/outline.htm.

Accessed March 7, 2002.

Making Health Communication Programs Work

5

THEORIES GUIDE ACTION TO INCREASE MAMMOGRAPHY USE

Fox Chase Cancer Center, in cooperation with area managed care organizations, designed

a program that was based on key elements of the health belief model to encourage women

to have regular mammograms. Selected women received educational materials explaining

that virtually all women are at risk for breast cancer, regardless of the absence of

symptoms, and that risk increases with age (susceptibility). The materials stressed that

early detection brings not only the best chance of cure but also the widest range of

treatment choices (benefit). Women received a letter stating their physician’s support (cue

to action) and a coupon for a free mammogram (to overcome the cost barrier). Those who

did not have a mammogram within 90 days received different forms of reminders (cues to

action). In the most intensive reminder, a telephone counselor called selected women to

review their perceptions about susceptibility, benefits, and barriers. Program evaluation

showed that mammography use increased substantially.

The Fox Chase program also applied social learning theory in developing interventions to

encourage physician support of mammography and to improve clinical breast

examinations (CBEs). The planners examined the environmental and situational factors

that might affect physician behavior and tried to change the low expectations of

physicians about the benefits of breast screening. The interventions included

observational learning by watching an expert perform a CBE, an opportunity to increase

self-efficacy by practicing CBE with the instructor, and the use of a feedback report and

CME credits to reinforce physician skills.

In taking a community approach to change, a UCLA mammography program used a

diffusion of innovations model. Community analysis showed that women who were early

adopters (leaders) already had a heightened awareness of the value of mammography. To

reach middle adopters, the program mobilized the social influence of the early adopters by

using volunteers who had breast cancer to provide mammography information. The

program also provided highly individualized educational strategies linked to social

interaction approaches to reach late adopters. A social marketing framework influenced

the program’s planning approach, and media materials incorporated the health belief

model to promote individual behavior change.

Note. From “Audiences and Messages for Breast and Cervical Cancer Screenings,” by B. K. Rimer,

1995, Wellness Perspectives: Research, Theory, and Practice, 11(2), pp. 13–39. Copyright by University

of Alabama. Adapted with permission.

6

Introduction

INTRO

Communication programs can take

advantage of the strengths of each of the

above by using multiple methods. A program

to decrease tobacco use among youth, for

example, could include:

• Paid advertising to ensure that youth are

exposed to on-target, unfiltered

motivational messages

• Media advocacy to support regulatory or

policy changes to limit access to tobacco

• Public relations to support

anti-tobacco attitudes

• Media literacy instruction in schools

to reduce the influence of the

tobacco industry

• Entertainment education and advocacy

to decrease the depiction of tobacco use

in movies

• Partnerships with commercial enterprises

(such as retail chains popular

among youth) to spread the

anti-smoking message

Using multiple methods increases the need

for careful planning and program

management to ensure that all efforts are

integrated and consistently support program

goals and objectives.

Planning Frameworks, Theories,

and Models of Change

Sound health communication development

should draw upon theories and models that

offer different perspectives on the intended

audiences and on the steps that can

influence their change. No single theory

dominates health communication because

health problems, populations, cultures, and

contexts vary. Many programs achieve the

greatest impact by combining theories to

address a problem. The approach to health

communication we use in this book is based

on the social marketing framework.

(See Appendix B for an overview of some

other relevant theoretical models.) Social

marketing concentrates on tailoring

programs to serve a defined group and is

most successful when it is implemented as

NATIONAL OBJECTIVES FOR RESEARCH

AND

EVALUATION

The Health Communication chapter of

Healthy People 2010, the nationwide

health promotion and disease

prevention agenda, identifies increasing

the proportion of health

communication activities that include

research and evaluation as one of six

objectives for the field for the next

decade (objective 11-3). This objective

focuses attention on the need to make

research and evaluation integral parts of

initial program design. Research and

evaluation are used to systematically

obtain the information needed to

refine the design, development,

implementation, adoption, redesign,

and overall quality of a

communication intervention.

Making Health Communication Programs Work

7

a systematic, continuous process that is

driven at every step by decision-based

research, which is used as feedback to

adjust the program.*

Why Use Theories and Models?

Although theories cannot substitute for

effective planning and research, they offer

many benefits for the design of health

communication programs. At each stage of

the process outlined in this book, theories

and models can help answer key questions,

such as:

• Why a problem exists

• Whom to select

• What you need to know about the

population/intended audience before

taking action

• How to reach people and make an impact

• Which strategies are most likely to

cause change

Reviewing theories and models can suggest

factors to consider as you formulate your

objectives and approach, and can help you

determine whether specific ideas are likely

to work. Theories and models can guide

message and materials development, and

are also useful when you decide what to

evaluate and how to design evaluation tools.

How Market Research and Evaluation

Fit Into Communication Programs

Conducting market research is vital to

identifying and understanding intended

audiences and developing messages and

strategies that will motivate action.

Evaluations conducted before, throughout,

and after implementation provide data on

which to base conclusions about success or

failure and help to improve current and

future communication programs.

Evaluation should be built in from the start,

not tacked on to the end of a program.

Integrating evaluation throughout planning

and implementation ensures that you:

• Tailor messages, materials, and activities

to your intended audience

• Include evaluation mechanisms (e.g.,

include feedback forms with a

community guide)

• Define appropriate, meaningful,

achievable, and time-specific

program objectives

Evaluating your program’s communication

efforts enables you to:

• Understand what is and is not working,

and why

• Improve the effort while it is under way

and improve future efforts

• Demonstrate the value of the program to

interested parties such as partners,

funding agencies, and the public

• Help program staff see how its work

affects the intended audiences

In this book, we address appropriate

evaluation activities for each stage; see the

Communication Research Methods section

for a description of the different types of

research and evaluation that support each

stage of the health communication

process. See Appendix A for sample

forms and instruments.

* From Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion

Practice (NIH Publication No. 97-3896), by the National

Cancer Institute, 1995. Bethesda, MD. In the

public domain.

8

Introduction

INTRO

Selected Readings

Andreasen, A. (1995). Marketing social

change: Changing behavior to promote

health, social development, and the

environment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Backer, T. E., Rogers, E. M., & Sopory, P.

(1992). Designing health communication

campaigns: What works. Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of

thought and action: A social cognitive theory.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

(2001). CDCynergy 2001 [CD-ROM]. Atlanta.

Glanz, K., Lewis, F. M., & Rimer, B. K.

(Eds.). (1997). Health behavior and health

education: Theory, research, and practice

(2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Glanz, K., & Rimer, B. K. (1995). Theory at a

glance: A guide for health promotion

practice (NIH Publication No. 97-3896).

Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Goldberg, M. E., Fishbein, M. F., &

Middlestadt, S. E. (Eds.). (1997). Social

marketing: Theoretical and practical

perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Green, L. W., & Kreuter, M. W. (1999). Health

promotion planning: An educational and

ecological approach (3rd ed.). Mountain

View, CA: Mayfield.

Maibach, E., & Parrott, R. L. (Eds.). (1995).

Designing health messages: Approaches

from communication theory and public

health practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

National Cancer Institute. (1993). A picture

of health (NIH Publication No. 94-3604).

Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services.

Rimer, B. K. (1995). Audiences and

messages for breast and cervical cancer

screenings. Wellness Perspectives:

Research, Theory, and Practice, 11(2),

13–39.

Siegel, M., & Doner, L. (1998). Marketing

public health: Strategies to promote social

change. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen.

U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services. (2000). Healthy people 2010 (2nd

Ed.; in two volumes: Understanding and

improving health and Objectives for

improving health.). Washington, DC: U.S.

Government Printing Office.

Making Health Communication Programs Work

9

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

OVERVIEW

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

OVERVIEW

Overview: The Health

Communication Process

In This Section:

• How the approach used in this book will help your organization produce

and implement a health communication program

• Each stage in the health communication process

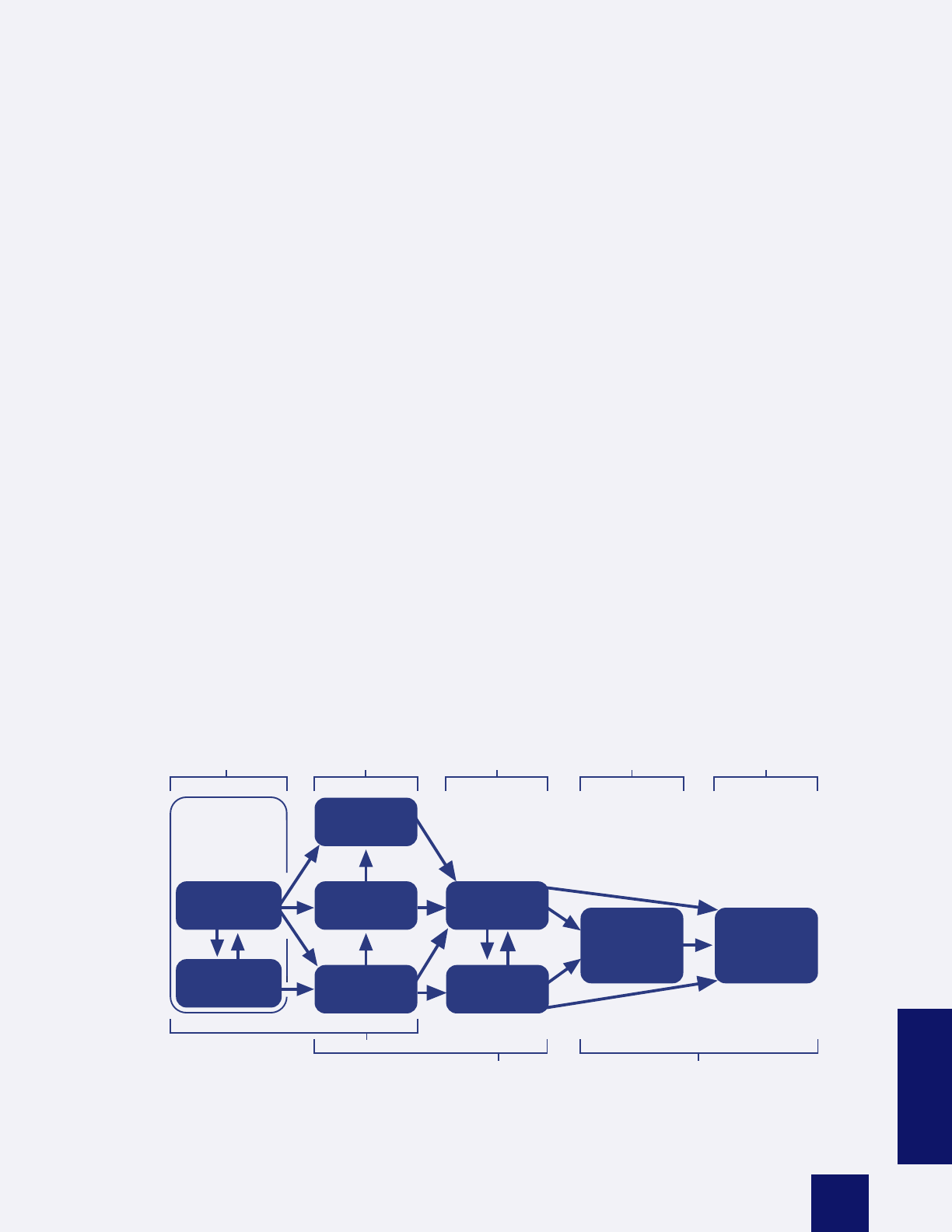

The Stages of the Health Communication Process

For a communication program to be successful, it must be based on an

understanding of the needs and perceptions of the intended audience. In

this book, we incorporate tips on how to learn about the intended audience’s

needs and perceptions in each of the program stages. Remember, these

needs and perceptions may change as the project progresses, so be

prepared to make changes to the communication program as you proceed.

To help with planning and developing a health communication program, we

have divided the process into four stages: Planning and Strategy

Development; Developing and Pretesting Concepts, Messages, and

Materials; Implementing the Program; and Assessing Effectiveness and

Making Refinements. The stages constitute a circular process in which the

last stage feeds back into the first as you work through a continuous loop of

planning, implementation, and improvement.

1

2

3

4

Health

Communication

Program

Cycle

Planning and

Strategy

Development

Developing

and Pretesting

Concepts,

Messages,

and Materials

Implementing

the Program

Assessing

Effectiveness

and Making

Refinements

Use this book to produce and implement a

plan for a communication program. The final

plan will include the following components:

• General description of the program,

including intended audiences, goals,

and objectives

• Market research plans

• Message and materials development and

pretesting plans

• Materials production, distribution, and

promotion plans

• Partnership plans

• Process evaluation plan

• Outcome evaluation plan

• Task and time table

• Budget

Because this process is not linear, do not

expect to complete a stage and then move

to the next, never to go back.You will be

exploring opportunities, researching issues,

and refining plans and approaches as your

organization implements the program. This

ongoing, iterative process characterizes a

successful communication program.

To help work through program planning and

development, we suggest many steps within

each stage.You may not find all of the steps

suggested in each stage feasible for your

program, or even necessary. As you plan,

carefully examine available resources and

what you want to accomplish with the

program and then apply the steps that are

appropriate for you. However, if you carefully

follow the steps described in each stage of

the process, your work in the next phase

may be more productive.

Each of the four stages is described here;

they are described in more detail in the

subsequent sections of this book.

Stage 1: Planning and Strategy

Development

In this book, all planning is discussed within

the Planning and Strategy Development

section, but the concepts you learn there

apply across the life cycle of a

communication program. During Stage 1

you create the plan that will provide the

foundation for your program. By the end of

Stage 1, you will have:

• Identified how your organization can use

communication effectively to address a

health problem

• Identified intended audiences

• Used consumer research to craft a

communication strategy and objectives

• Drafted communication plans, including

activities, partnerships, and baseline

surveys for outcome evaluation

Planning is crucial for the success of any

health communication program, and doing

careful work now will help you avoid having

to make expensive alterations when the

program is under way.

Stage 2: Developing and Pretesting

Concepts, Messages, and Materials

In Stage 2, you will develop message

concepts and explore them with the

intended audience using qualitative

research methods. By the end of Stage 2,

you will have:

• Developed relevant, meaningful messages

• Planned activities and drafted materials

• Pretested the messages and materials

with intended-audience members

12

Overview

OVERVIEW

Getting feedback from intended audiences

when developing messages and materials is

crucial for the success of every

communication program. Learning now what

messages are effective with the intended

audiences will help you avoid producing

ineffective materials.

Stage 3: Implementing the Program

In Stage 3, you will introduce the fully

developed program to the intended

audience. By the end of Stage 3, you

will have:

• Begun program implementation,

maintaining promotion, distribution, and

other activities through all channels

• Tracked intended-audience exposure and

reaction to the program and determined

whether adjustments were needed

(process evaluation)

• Periodically reviewed all program

components and made revisions

when necessary

Completing process evaluations and making

adjustments are integral to implementing the

program and will ensure that program

resources are always being used effectively.

Stage 4: Assessing Effectiveness and

Making Refinements

In Stage 4, you will assess the program

using the outcome evaluation methods you

planned in Stage 1. By the end of Stage 4,

you will have:

• Assessed your health

communication program

• Identified refinements that would

increase the effectiveness of future

program iterations

Because program planning is a recurring

process, you will likely conduct planning,

management, and evaluation activities

described in Stages 1–4 throughout the

life of the program.

Making Health Communication Programs Work

13

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

STAGE 1

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

GuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuideAPlanner’sGuide

Planning and

Strategy Development

In This Section:

• Why planning is important

• Six steps of the planning process

• Assessing health issues and identifying solutions

• Defining communication objectives

• Defining intended audiences

• Exploring communication settings, channels, and activities

• Identifying potential partners and collaborating

• Developing a communication strategy and drafting communication

and evaluation plans

• Common myths about planning

Questions to Ask and Answer:

• What health problem are we addressing?

• What is occurring versus what should be occurring?

• Whom does the problem affect, and how?

• What role can communication play in addressing the problem?

• How and by whom is the problem being addressed? Are other

communication programs being planned or implemented?

(Look outside of your own organization.)

• What approach or combination of approaches can best influence the

problem? (Communication? Changes in policies, products, or services?

All of these?)

• What other organizations have similar goals and might be willing to

work on this problem?

• What measurable, reasonable objectives will we use to define success?

• What types of partnerships would help achieve the objectives?

• Who are our intended audiences? How will we learn about them?

• What actions should we encourage our intended audiences to take?

• What settings, channels, and activities are most appropriate for reaching

our intended audiences and the goals of our communication objectives?

(Interpersonal, organizational, mass, or computer-related media?

Community? A combination?)

• How can the channels be used most effectively?

• How will we measure progress? What baseline information will we use to

conduct our outcome evaluation?

STAGE 1

Why Planning Is Important

The planning you do now will provide the

foundation for your entire health

communication program. It will enable your

program to produce meaningful results

instead of just boxes of materials. Effective

planning will help you:

• Understand the health issue you

are addressing

• Determine appropriate roles for

health communication

• Identify the approaches necessary to bring

about or support the desired changes

• Establish a logical program

development process

• Create a communication program that

supports clearly defined objectives

• Set priorities

• Assign responsibilities

• Assess progress

• Avert disasters

Under the pressure of deadlines and

demands, it is normal to think, “I don’t have

time to plan; I have to get started NOW.”

However, following a strategic planning

process will save you time. Because you will

define program objectives and then tailor

your program’s activities to meet those

objectives, planning will ensure that you

don’t spend time doing unnecessary work.

Program objectives are generally broader

than communication objectives, described

in step 2 on page 20, and specify the

outcomes that you expect your entire

program to achieve. Many of the planning

activities suggested in this chapter can be

completed simultaneously. Even if your

program is part of a broader health

promotion effort that has an overall plan, a

plan specific to the communication

component is necessary.

Planning Steps

This chapter is intended to help you design

a program plan. The health communication

planning process includes the following six

steps explained in this chapter:

1. Assess the health issue or problem and

identify all the components of a possible

solution (e.g., communication as well as

changes in policy, products, or services).

2. Define communication objectives.

3. Define and learn about

intended audiences.

4. Explore settings, channels, and activities

best suited to reach intended audiences.

5. Identify potential partners and develop

partnering plans.

6. Develop a communication strategy for

each intended audience; draft a

communication plan.

To complete this process, use the

Communication Program Plan template in

Appendix A to help ensure that you don’t

miss any key points.

1. Assess the Health Issue/Problem and

Identify All Components of a Solution

The more you understand about an issue or

health problem, the better you can plan a

communication program that will address it

successfully. The purpose of this initial data

collection is to describe the health problem

or issue, who is affected, and what is

occurring versus what should be occurring.

Doing this will allow you to consider how

communication might help address the

issue or problem. In this step, review and

gather data both on the problem and on

what is being done about it.

16

Planning and Strategy Development

Review Available Data

• Community service agencies (for related

To collect available data, first check for

sources of information in your agency or

organization. Identify gaps and then seek

outside sources of information. Sources and

availability of information will vary by issue.

The types of information you should (ideally)

have at this stage include descriptions of:

• The problem or issue

• The incidence or prevalence of the

health problem

• Who is affected (the potential intended

audience), including age, sex, ethnicity,

economic situation, educational or reading

level, place of work and residence, and

causative or preventive behaviors. Be sure

to include more information than just

basic demographics

• The effects of the health problem on

individuals and communities (state,

workplace, region, etc.)

• Possible causes and preventive measures

• Possible solutions, treatments,

or remedies

To find this information, search these

common data sources:

• Libraries (for journal articles and texts)

• Health-related resources on the Internet

• Sources of health statistics (a local

hospital, a state health department, the

National Center for Health Statistics on the

CDC Web site)

• Administrative databases covering

relevant populations

• Government agencies, universities,

and voluntary and health

professional organizations

• Clearinghouses

service-use data)

• Corporations, trade associations,

and foundations

• Polling companies (for intended audience

knowledge and attitudes)

• Depositories of polling information (e.g.,

the Roper Center)

• Chambers of commerce

• Advertising agencies, newspapers,

and radio and television stations

(for media-use data, buying and

consumption patterns)

Both published and unpublished reports

may be available from these sources. A

number of federal health information

clearinghouses and Web sites also provide

information, products, materials, and

sources of further assistance for specific

health subjects. A helpful first step in

planning may be to contact the appropriate

Web sites and the health department to

obtain information on the health issue your

program is addressing. See Appendix C,

Information Sources, for listings of

additional sources of information, including

Internet resources.

Identify Existing Activities and Gaps

Find out what other organizations are doing

to address the problem, through

communication and other approaches,

such as advocating for policy or

technological changes. Contact these

organizations to discuss:

• What they have learned

• What information or advice they may have

to help you plan

• What else is needed (what gaps exist in

types of change needed, media or

activities available, intended audiences

STAGE 1

Making Health Communication Programs Work

17

served to date, messages and materials

directed at different stages of intended

audience behavior change)

• Opportunities for cooperative ventures

Gather New Data as Needed

You may find that the data you have

gathered does not give enough insight into

the health problem, its resolution, or

knowledge about those who are affected in

order to proceed. In other instances, you

may have enough information to define the

problem, know who is affected, and identify

the steps that can resolve it, but other

important information about the affected

populations may be unavailable or outdated.

To conduct primary research to gather more

information, see the Communication

Research Methods section.

Sometimes it is impossible to find sufficient

information about the problem. This may be

because the health problem has not yet

been well defined. In this case, you might

decide that a communication program is an

inappropriate response to that particular

problem until more becomes known.

Identify All Components of a Solution

Adequately addressing a health problem

often requires a combination of the

following approaches:

• Communication (to the general public,

patients, health care providers,

policymakers—whoever needs to make or

facilitate a change)

• Policy change (e.g., new laws, regulations,

or operating procedures)

• Technological change (e.g., a new or

redesigned product, drug, service, or

treatment; or changing delivery of existing

products, drugs, services, or treatments)

Yet all too often we rely on health

communication alone and set unrealistic

expectations for what it can accomplish. It is

vitally important to identify all of the

components necessary to bring about the

desired change and then to carefully

consider which of these components is

being—or can be—addressed. For example,

consider a woman who needs a

mammogram. The mammogram graphic

shows some of the problems that may

Communication Strategy

A Case Study: Mammogram

Solution: Requires

Communication

Strategy

Communication

to Doctors

Persuade doctors to

give mammogram

referrals to all women

in the appropriate

age group

Communication

to Women

Present the benefits

(that women think are

important) of getting a

mammogram that will

outweigh her fears

My doctor

doesn’t

recommend a

mammogram.

I don’t think

I need it. I’m

afraid of getting a

mammogram.

Solution: Requires

Change in Policy

and Resources

My health

insurance

doesn’t cover

mammograms.

I can’t travel

40 miles to get a

mammogram and

I can’t miss

work.

Policy

Mandate coverage of

mammograms in

accordance with

screening guidelines

Technology

Outfit a van with

mammography

equipment and send

to her neighborhood

during nonworking

hours

18

Planning and Strategy Development

USING COMMUNICATION TO SUPPORT POLICY CHANGE

The goal of a communication campaign is not always to teach or to influence behavior; it

can also begin the process of changing a policy to increase health and wellness. This

might mean getting community leaders excited about a new “rails to trails” project or

working to bring up the issue of a lack of low-income housing. In each case, the final goal

(i.e., helping people exercise by increasing the number of walking/biking trails, making

sure that everyone in the community has a safe place to live by assigning more

apartments in newly built housing to low-income residents) is more than a

communication campaign can accomplish. However, the initial goal (gaining the support

of decision-makers who can change current policy) can be met.

One of the most popular and effective ways to build support for policy change is to work

with the media. Use the following questions to help plan your message:

• What is the problem you are highlighting?

• Is there a solution to it? If so, what is it?

• Whose support do you need to gain to make the solution possible?

• What do you need to do or say to get the attention of those who can make the

solution happen?

Once you have developed your message, create a media list that includes organizations,

such as newspapers and television stations; individuals, such as reporters, editors, and

producers; and other contacts. Keep this list updated as you communicate your message

and work to change policy. The following are a few methods to use:

• News releases

• Interviews

• Letters to the editor

• Media conferences

Media strategies are not the only way to build support for policy change. Also consider

attending and speaking at local meetings, approaching issue decision-makers either in

person or by letter, or working with and educating community members who are affected.

STAGE 1

Note. From American Public Health Association. APHA Media Advocacy Manual 2000.

Washington, DC. Adapted with permission.

Making Health Communication Programs Work

19

occur and potential solutions for each.

Solutions that communication programs

can help develop are highlighted.

Determine Whether Health Communication

Is Appropriate for the Problem and

Your Organization

Create a map that diagrams the

components of a problem and the steps

necessary to solve it (as in the mammogram

graphic) to help you determine a possible

role for health communication. In some

cases, health communication alone may

accomplish little or nothing without policy,

technological, or infrastructure changes

(e.g., successfully increasing physical

activity of employees in the workplace might

require employer policy changes to allow for

longer breaks or infrastructure changes

such as new walking paths). In some

instances, effective solutions may not yet

exist for a communication program to

support. For example, no treatment may

exist for an illness, or a solution may require

services that are not yet available. In these

cases, decide either to wait until other

program elements are in place or to

develop communication strategies directed

to policymakers instead of consumers

or patients.

If you determine that health communication

is appropriate, ask the following questions to

consider whether your organization is best

suited to carry it out:

• Does the organization have (or can it

acquire) the necessary expertise

and resources?

• Does the organization have the necessary

authority or mandate?

• Will the organization be duplicating efforts

of others?

• How much time does the organization

have to address this issue?

• What, if anything, can be accomplished

in that time?

2. Define Communication Objectives

Defining communication objectives will help

you set priorities among possible

communication activities and determine the

message and content you will use for each.

Once you have defined and circulated the

communication objectives, they serve as

a kind of contract or agreement about the

purpose of your communication, and

they establish what outcomes should

be measured.

It is important to create achievable

objectives. Many communication efforts are

said to fail only because the original

objectives were wildly unreasonable. For

example, it is generally impossible to

achieve a change of 100 percent. If you plan

to specify a numerical goal for a particular

objective, an epidemiologist or statistician

can help you determine recent rates of

change related to the issue so that you have

some guidance for deciding how much

change you think your program can achieve.

(Remember that commercial marketers

often consider a 2 to 3 percent increase in

sales to be a great success.) Fear of failure

should not keep you from setting

measurable objectives. Without them, there

is no way to show your program has

succeeded or is even making progress

along the way, which could reduce support

for the program among your supervisors,

funding agencies, and partners.

Because objectives articulate what the

communication effort is intended to do,

they should be:

• Supportive of the health program’s goals

• Reasonable and realistic (achievable)

• Specific to the change desired, the

population to be affected, and the time

20

Planning and Strategy Development

HOW COMMUNICATION CONTRIBUTES TO COMPLEX BEHAVIOR CHANGE

One can imagine how the process of change occurs: A woman sees some public service

announcements (PSAs) and a local TV health reporter’s feature telling her about the

“symptomless disease”—hypertension. She checks her blood pressure in a newly accessible

shopping mall machine, and the results suggest a problem. She tells her spouse, who has

also seen the ads, and he encourages her to have it checked. She goes to a physician who

confirms the presence of hypertension and encourages her to change her diet and return

for monitoring.

The physician has become more sensitive to the issue because of a recent article in the

Journal of the American Medical Association, some recommendations from a specialist

society, and a conversation with a drug retailer as well as informal conversations with

colleagues and exposure to television discussion of the issue.

Meanwhile, the patient talks with friends at work or family members about her

experience. They also become concerned and go to have their own pressure checked. She

returns for another checkup and her pressure is still elevated although she has reduced her

salt intake. The physician decides to treat her with medication. The patient is ready to

comply because all the sources around her—personal, professional, and media—are telling

her that she should.

This program is effective not because of a PSA or a specific program of physician

education. It is successful because the National High Blood Pressure Education Program

has changed the professional and public environment as a whole around the issue

of hypertension.

Note. From “Public Health Education and Communication as Policy Instruments for Bringing About

Changes in Behavior,” by R. Hornik. In Social Marketing: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives (pp.

49–50), by M. E. Goldberg, M. Fishbein, and S. E. Middlestadt (Eds.), 1997, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates. Adapted with permission.

period during which change should

(you’ll design strategies and tactics for

take place

getting there later). Develop reasonable

• Measurable, to allow you to track progress

communication objectives by looking at the

toward desired results

health program’s goal and asking, “What

can communication feasibly contribute to

• Prioritized, to direct the allocation

attaining this goal, given what we know

of resources

about the type of changes the intended

audiences can and will make?”

Be Reasonable

Communication efforts alone cannot achieve

Objectives describe the intermediate steps

all objectives. Appropriate purposes for

that must be taken to accomplish broader

communication include:

goals; they describe the desired outcome,

but not the steps involved in attaining it

STAGE 1

Making Health Communication Programs Work

21

• Creating a supportive environment for a

change (societal or organizational) by

influencing attitudes, beliefs, or policies

• Contributing to a broader behavior

change initiative by offering messages

that motivate, persuade, or enable

behavior change within a specific

intended audience

Raising awareness or increasing knowledge

among individuals or the organizations that

reach them is also feasible; however, do not

assume that accomplishing such an

objective will lead to behavior change. For

example, it is unreasonable to expect

communication to cause a sustained

change of complex behaviors or

compensate for a lack of health care

services, products, or resources.

The ability and willingness of the intended

audience to make certain changes also

affect the reasonableness of various

communication objectives. Keep this in mind

as you define the intended audiences in

planning step 2.Your objectives will be

reasonable for a particular intended

audience only if audience members both

can make a particular behavior change and

are willing to do so.

Be Realistic

Once your program has developed

reasonable communication objectives,

determine which of them are realistic, given

your available resources, by answering

these questions:

• Which objectives cover the areas that

most need to reach the program goal?

• What communication activities will

contribute the most to addressing

these needs?

PLANNING TERMS

Goal

The overall health improvement that an

organization or agency strives to create

(e.g., more eligible cancer patients will

take part in cancer clinical trials, or

more Americans will avoid fatal heart

attacks). A communication program