Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

520 Lafayette Road North | Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 |

651-296-6300 | 800-657-3864 | Or use your preferred relay service. | Info.pca@state.mn.us

This report is available in alternative formats upon request, and online at www.pca.state.mn.us.

Document number: w-sw7-22

Legislative charge

Minn. Stat. § 473.149 - A metropolitan long range policy plan for solid waste management, prepared by

the Pollution Control Agency, sets goals and policies for the metropolitan solid waste system. This plan

includes goals and policies for solid waste management, including recycling consistent with section

115A.551 and household hazardous waste management consistent with section 115A.96, subdivision 6.

The MPCA shall include specific and quantifiable metropolitan objectives for abating, to the greatest

feasible and prudent extent, the need for and practice of land disposal of mixed municipal solid waste

and specific components of the solid waste stream.

Authors

Alison Cameron

Cathy Latham

Barbara Monaco

Peder Sandhei

Contributors/acknowledgements

Annika Bergen

Amanda Cotton

Tim Farnan

John Gilkeson

Wayne Gjerde

Susan Heffron

Colleen Hetzel

Greg Kvaal

Sherri Nachtigal

Cliff Shierk

Jennifer Volkman

Kayla Walsh

Melissa Wenzel

Maggie Yauk

Editing and graphic design

Scott Andre

Kevin Gaffney

Jennifer Holstad

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

i

Acronyms and initialisms

CII commercial, industrial, institutional

CON Certificate of Need

CSWMP County Solid Waste Management Plans

Demolition debris construction and demolition debris

EJ Environmental Justice

EPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

EPD Environmental Product Declaration

EPR Extended Producer Responsibility

GHGs Greenhouse gases

GHGe Greenhouse gas emissions

HERC Hennepin Energy Recovery Center

HHW household hazardous waste

ISW industrial solid waste

LRDG Local Recycling Development Grants

MLAA Metropolitan Landfill Abatement Account

MMSW mixed municipal solid waste

MN USGBC Minnesota U.S. Green Building Council

MPP Metro Policy Plan

MSW municipal solid waste

MnDOT Minnesota Department of Transportation

MPCA Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

MRF materials recovery facility

PFAS Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances

PUC Minnesota Public Utilities Commission

RDF refuse derived fuel

RMD recycling market development

ROD restriction on disposal

SMM Sustainable Materials Management

SSO source separated organics

TCMA Twin Cities Metropolitan Area

WARM waste reduction model

WMA Waste Management Act

WTE waste-to-energy

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

ii

Contents

Acronyms and initialisms ................................................................... i

Figures .............................................................................................. iii

Tables ............................................................................................... iv

Part one: Introduction and background ..............................................1

Part two: Framework for change .......................................................6

Part three: MPP 2022-2042 .............................................................. 10

Appendix A: Overview of the current Twin Cities Metropolitan Area

solid waste management system ...................................................... 53

Appendix B: Environmental justice review ........................................ 62

Appendix C: Predrafting notice ......................................................... 66

Appendix D: Procedures, standards, and criteria .............................. 69

Appendix E: Glossary ........................................................................ 85

Appendix F: Metro Policy Plan MMSW forecast ................................ 91

Appendix G: Strategy table ............................................................... 95

Appendix H: Air Toxic and Cumulative Impact Rules ......................... 98

Appendix I: Public Comments and Responses ................................. 100

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

iii

Figures

Figure 1. TCMA County map ......................................................................................................................... 2

Figure 2. Minnesota’s solid waste management hierarchy of preferred methods ...................................... 6

Figure 3. Total MSW Generation Forecast with the 15% source reduction objective ............................... 11

Figure 4. Non-MSW and Ash Forecast ........................................................................................................ 12

Figure 5. LCA: a methodology for modeling the environmental impacts of a material or product

from raw material extraction through end-of-life management ............................................................... 13

Figure 6. TCMA MMSW management methods: past, present, and projection (SCORE and

Certification Reports) .................................................................................................................................. 17

Figure 7. Carbon emissions impact of different management types.......................................................... 20

Figure 8. Personal consumption expenditures ........................................................................................... 26

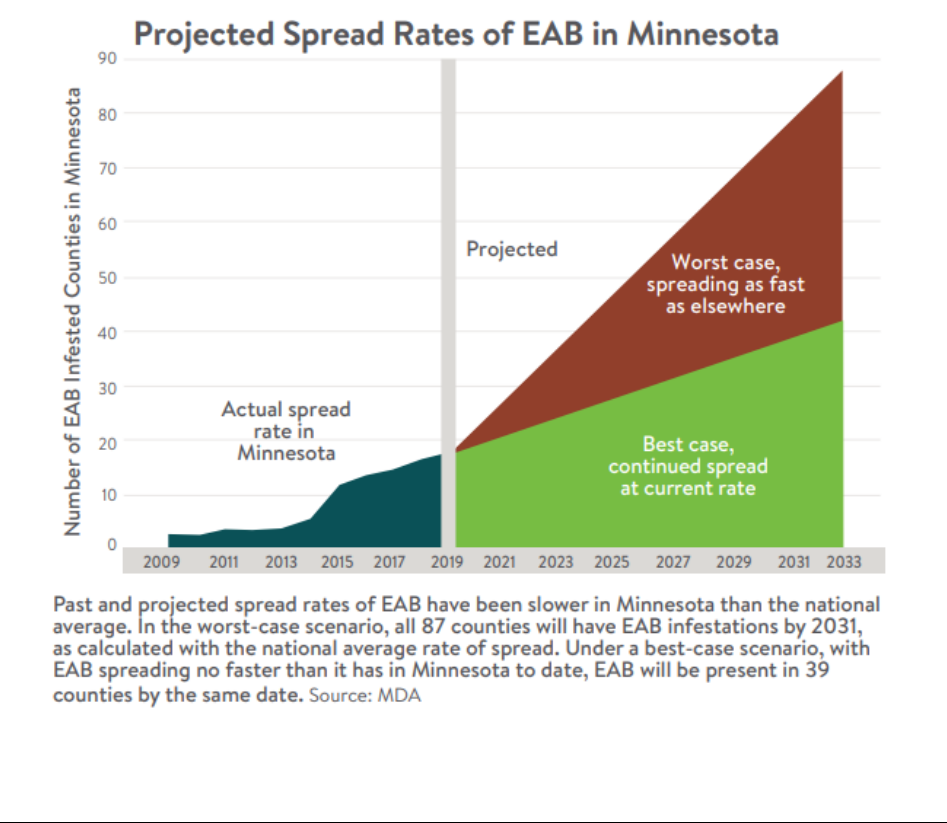

Figure 9. Projected county infestation impact in Minnesota due to EAB ................................................... 38

Figure 10. Total GHG generated by landfill and WTE from start of disposal through closure and

beyond ........................................................................................................................................................ 44

Figure 11. Municipal Solid Waste: Landfill vs. WTE .................................................................................... 45

Figure 12. Sustainable Building SMM Guidance from most to least preferred management

methods ..................................................................................................................................................... 50

Figure 13. EPA Wasted Food Scale preferred management methods ....................................................... 56

Figure 14. Map of solid waste facilities and EJ boundaries located within the TCMA ............................... 63

Figure 15. Map of solid waste facilities and EJ boundaries located within Minneapolis and

Saint Paul .................................................................................................................................................... 64

Figure 16. Reported and forecasted TCMA MMSW collection methods amounts in tons ........................ 93

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

iv

Tables

Table 1. Waste reduction system objectives in percentages and tons (2021-2042) .................................. 15

Table 2. MMSW management system objectives in percentages (2021-2042) ......................................... 16

Table 3. MMSW management system tonnages (Based on objectives in Table 2 in thousands of tons

[2010-2030]) ............................................................................................................................................... 16

Table 4. Monthly cost of residential MMSW service in the Richfield before and after organized

collection ..................................................................................................................................................... 33

Table 5. Existing resource recovery facility capacity serving the TCMA ..................................................... 46

Table 6. 2021 disposal in facilities that accept TCMA waste ...................................................................... 49

Table 7. Organics obligation by county for FY2020-2023 ........................................................................... 58

Table 8. Organics recovered in 2021 (in tons) (data from the 2021 SCORE report) ................................... 58

Table 9. Existing resource recovery facility capacity serving the TCMA ..................................................... 59

Table 10. Landfill locations accepting TCMA waste .................................................................................... 60

Table 11. Non-MMSW landfills accepting TCMA demolition debris .......................................................... 61

Table 12. Annual capacity (in tons) for the WTE facilities servicing the TCMA. ......................................... 92

Table 13. Total TCMA MMSW forecast by management method .............................................................. 93

Table 14. Strategy table with point values and interested parties ............................................................. 95

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

1

Part one: Introduction and background

In 1980, the Minnesota Legislature recognized the importance of waste management with the passage

of the Waste Management Act (WMA) in Minn. Stat. § 115A. This statute’s purpose is to protect the

state's natural resources and public health by improving integrated solid waste management. The

statute establishes the following hierarchy of preferred solid waste management practices, in order

from most to least beneficial to the environment:

1. Waste reduction and reuse

2. Waste recycling

3. Composting of source-separated compostable materials, including but not limited to, yard waste

and food waste

4. Resource recovery through mixed municipal solid waste (MMSW) composting or incineration

5. Land disposal which produces no measurable methane gas, or which involves the retrieval of

methane gas as a fuel to produce energy to be used on-site or for sale

6. Land disposal which produces measurable methane, and which does not involve the retrieval of

methane gas as a fuel to produce energy to be used on-site or for sale

The above hierarchy was established to achieve the following goals, as provided in Minn. Stat. §

115A.02(a):

1. Reduction in the amount and toxicity of waste generated

2. Separation and recovery of materials and energy from waste

3. Reduction in indiscriminate dependence on disposal of waste

4. Coordination of solid waste management among political subdivisions

5. Orderly and deliberate development and financial security of waste facilities including disposal

facilities

To avoid confusion as to which types of plans are being discussed, this document will be referred to as

the Metro Policy Plan (MPP); the plans the counties develop will be referred to as County Solid Waste

Management Plans (CSWMP). The language in the statutes, where quoted, is not changed and is

italicized for clarity.

Purpose of this Plan (MPP)

This MPP establishes the framework for managing the Twin Cities Metro Area's (TCMA) solid waste for

the next 20 years (2023-2043). It was prepared in accordance with the requirements of Minn. Stat. §

473.149. It will guide the development and activities of solid waste management and must be followed

by the counties in the TCMA. In addition to the counties, the MPCA, solid waste facilities, haulers,

businesses, and residents all have a role in implementing the MPP. The MPP supports the goals of the

WMA hierarchy, improving public health, reducing the reliance on landfills, conserving energy and

natural resources, and reducing pollution and greenhouse gas emissions (GHGe).

The TCMA includes Anoka, Carver, Dakota, Hennepin, Ramsey, Scott, and Washington counties.

Excluded cities from the TCMA are Northfield, Hanover, Rockford, and New Prague.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

2

Participants in the process

The MPCA staff held several meetings with stakeholders in advance of the release of the draft MPP.

Several public meetings were also held after the release of the draft MPP to gather input from other

MPP stakeholders, including members of the recycling and waste industry, counties, non-governmental

organizations (NGOs), and members of the public.

Figure 1. TCMA County map

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

3

How the MPP will be used by stakeholders

The MPP will guide all stakeholders in their roles to ensure that waste is managed to the highest and

best use.

The MPP will:

1. Inform waste generators (residents, businesses, public entities) about their roles and responsibilities

in waste management.

2. Educate generators about solid waste issues and services (both public and private) available to

them.

3. Identify and direct state agencies and county governments that provide assistance.

The MPP will outline the responsibility of the waste industry in providing future solid waste facilities and

services. For the purposes of this MPP, the “waste industry” includes all entities, public and private, that

collect and/or manage solid waste in some form, including recyclables, household hazardous waste

(HHW), and problem materials.

The MPP will rely upon organizations that support the reuse industry, including repair organizations and

non-government organizations, such as thrift stores.

The MPP will:

1. Provide guidance to counties and regional governmental entities in developing county solid waste

ordinances, work plans, and budgets.

2. Direct the MPCA oversight responsibilities, including administration of the Metropolitan Landfill

Abatement Account program, CSWMP reviews, and the MPCA’s approval of solid waste facility

permits and landfill certificates of need (CON).

3. Assist the MPCA in its regulatory, enforcement, and technical assistance functions that affect the

TCMA.

4. Contribute to policy discussions regarding solid waste legislation affecting the TCMA.

5. Influence local jurisdictions in the planning and provision of services to residents and businesses.

6. Manage waste in a way that minimizes adverse impacts on the environment including, but not

limited to, GHG reduction, resource conservation, and long-term legacy impacts as a result of land

disposal.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

4

Current system status

The TCMA solid waste system is the result of planning and

development that began with the 1980 WMA. Since 1980, much

has been accomplished.

• The TCMA recycles 45.2% of the MMSW generated. The

recent improvement is largely due to advances in organics

collection for food to people, food to livestock, source

separated organics (SSO) management, and yard waste

composting.

• Reuse and recycling activities contribute significantly to the

economy of the region.

• Resource recovery facilities that serve the TCMA are now

operating at full capacity.

• Resource recovery facilities manage 28% of the MMSW

generated.

• Land disposal has decreased by 18% since 2008.

• Problem materials such as major appliances, mercury-

containing products, and electronic waste are banned from

the MMSW stream, and infectious wastes are separately

managed.

• A system to collect and manage HHW is available to all

residents, and all seven counties participate in an

arrangement of shared reciprocity.

As a region, we should be proud of the advances we have

made because of the efforts from product producers, waste

generators, waste industry, residents, and government.

What challenges still exist?

The Minnesota solid waste system has faced several challenges over the

past six years. A few large issues have indirectly affected the solid waste

system in a negative way. These have slowed progress toward the

objectives in the previous MPP. To meet our environmental goals, the

following challenges will need to be further addressed.

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted all systems in Minnesota in 2020 and 2021. Transmission

of the virus among solid waste workers was a safety concern, and outbreaks among staff at materials

recovery facilities (MRFs) resulted in operational shutdowns. MRFs excelled at maintaining operations to

the extent possible. However, requests for disposal allowances were yielded during this time.

The TCMA experienced social unrest following the murder of George Floyd. Some of the large

Minneapolis MRFs shut down temporarily as a precautionary measure. Limited capacity exists in the

region to absorb the material processed at that those facilities. This led to a request to dispose of

recyclable material. Permission was granted for the one-time disposal of 59.7 tons of recyclables, which

represents .000006% of the 1,000,000 tons of recyclables generated in the TCMA in 2020.

These events highlighted the lack of contingency plans the TCMA has for recyclable, reusable, and

compostable materials. Maintaining and developing new end markets will continue to be important for

A new name for this plan

The MPCA expects the fair treatment

and meaningful involvement of

communities of color, Indigenous

communities, and low-income

communities in agency actions and

decisions that affect them. As the

state takes initial steps to

acknowledge its role in systemic

racism, we recognize the power of

language. Current Minnesota statute

refers to the solid waste plans that

metro counties develop as “master”

plans. The term “master”, which is

often defined as commanding

control or being eminently skilled,

has been identified as a word to

remove in certain contexts due to its

connection with the history of

masters and slavery in the United

States. While this statute remains

unchanged as of the release of this

plan, where possible, this plan uses

the name “county solid waste plan”

in place of “county master solid

waste plan”. A noted exception is the

use of “county master plan” in

Appendix D, to remain consistent

with current statute language. An

additional benefit to using the term

"county solid waste plan" is that it

harmonizes the language with the

term used for Greater Minnesota

counties.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

5

Minnesota’s long-term success. A recent example of this is WestRock’s unexpected closing of its

corrugated cardboard line, resulting in a reduction of 600 tons of daily capacity, creating a major impact

to local MRFs and haulers.

Success creates challenges, too. For example, an increase in organics collection programs throughout

the TCMA point to the need for more planned programs in the coming years. Despite anticipated

increases in feedstock, there is not a corresponding increase in organics processing capacity in the

region. To meet our organics objectives, additional capacity to process organics will be necessary.

Minnesota’s changing climate is creating stresses for the solid waste system, as severe weather events

increase in frequency. Structural damage from flooding, tornados, and strong hail-producing

thunderstorms generates large amounts of solid waste. Downed trees put pressure on the yard waste

and composting facilities. The rise of EAB and other tree diseases compounds this issue as trees in

Minnesota are dying at an increasing rate. The wood from the trees affected by EAB cannot be

transported out of quarantine zones, leaving local entities to handle large volumes of wood waste

without perpetuating the spread of the EAB. The TCMA will need to identify ways to manage the

onslaught of wood waste over the coming years. Management solutions are needed to handle

generated wood safely and efficiently.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a significant challenge. Invented in the 1930s, PFAS are

still commonly used for their water- and grease-resistant properties in many industrial applications and

consumer products such as carpeting, waterproof clothing, upholstery, food paper wrappings,

cookware, personal care products, fire-fighting foams, and metal plating. PFAS are persistent and can

bioaccumulate, meaning the amount builds up in the body over time. When landfilled, PFAS migrates

into the leachate, which is treated at a wastewater treatment facility. With no existing removal systems

installed at landfills or wastewater plants to remove PFAS, the treated wastewater is discharged into

surface water. It is not clear if waste-to-energy (WTE) facilities maintain the high temperatures required

to destroy PFAS. The waste industry is in the process of identifying ways to address this unusual class of

chemicals. As the solid waste system continues to evolve, adaptations are needed to safely manage new

materials.

Establishing reuse and recycling markets for new additional materials is imperative to meet reuse and

recycling goals and other objectives in the MPP. Market development is a complicated task requiring

considerable lead time. New materials that can be recycled must be generated with enough volume to

justify and sustain a business model.

Finally, the closure of the Great River Energy (GRE) processing and WTE facility has resulted in more

than 250,000 tons of waste going to landfill. This closure directly increased landfill expansions in the

TCMA. In many ways, the GRE closure was the result of an intersection of waste and energy policy.

Minnesota needs to figure out how to manage the policy nexus for these facilities. The energy created at

these facilities is not cost competitive with wind and solar and is not universally viewed as a clean

energy source. However, the important role they serve in solid waste management should not be

underscored. Left unresolved, other resource recovery facilities may follow suit. Without achieving

greater waste diversion and reduction rates, that will result in an increased amount of waste being land-

disposed.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

6

Part two: Framework for change

This section of the MPP lays out a framework for a regional vision, key themes, goals, and policies. This

framework will guide all decisions of the MPCA, regional governing entities, metropolitan counties, solid

waste facilities, haulers, and other stakeholders with respect to the TCMA solid waste system.

Vision

This MPP is designed to help stakeholders exceed the benchmarks established in state law. The vision is

that the TCMA will put more emphasis on the following:

• Pollution prevention

• Sustainable materials management (SMM)

• Conservation of natural resources and energy

• Reduced reliance on landfills and WTE

• Reduced toxicity of waste

• Equitable improvement in public health for all residents

• Supporting the economy

• Reducing GHGe and the impacts of climate change

The MPP sets forth a vision of sustainability for the TCMA solid waste management system. The TCMA is

a sustainable community that minimizes waste, prevents pollution, promotes efficiency, reduces GHGe

and the impacts of climate change, saves energy, reduces toxicity, and develops resources to revitalize

local economies. The integrated waste management system is an essential component of the

infrastructure of a sustainable community.

Solid waste is managed according to the principles of SMM that support sustainable communities and

environments. The benefits of sustainable and healthy communities are shared equally throughout the

region by all residents. The solid waste management hierarchy is central to attaining the twin objectives

of sustainability and proper solid waste management because it emphasizes the higher end

management methods.

Figure 2. Minnesota’s solid waste management hierarchy of preferred methods

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

7

Key themes

The following key themes underlie all elements of the MPP.

SMM offers a systematic approach to using and reusing materials more productively over their entire

life cycles. SMM considers the environmental impact of the entire life cycle, not just disposal. This

holistic approach emphasizes management methods at the top of the waste hierarchy as well as

reducing toxicity. These methods have greater environmental benefits. For example, preventing food

waste is more impactful than increasing glass recycling rates.

GHGe reductions can be found throughout the solid waste management system. There are potential

reductions in GHGe to be found throughout the life cycle of products and in the waste management

system. This is particularly true at the top of the hierarchy and the design phase of a product when

GHGe can be avoided altogether. Other system changes can affect GHGe in other sectors. For example,

organized collection reduces the number of heavy truck miles and emissions.

The benefits and burdens of the solid waste management system must flow equally to everyone. The

MPCA is committed to ensuring that pollution does not have a disproportionate impact on any group of

people. This is a principle of environmental justice. Decisions about siting solid waste facilities should

include all stakeholders. Translating educational materials into the languages spoken in the TCMA is

important, as is including people who have not traditionally had a voice in decisions that affect them.

EPR presents great opportunities for shifting the burden of management from the counties and cities

to the producers. Product stewardship and extended producer responsibility (EPR) is a policy approach

to extend the producer’s responsibility to include environmental impacts from all stages of the product’s

life cycle. This includes incentives for durability, reusability, toxicity reduction, and finding the highest

and best use of materials and waste. In current practice, product stewardship requires manufacturers to

share in the physical and financial responsibility of collecting and recycling products at the end of their

useful life.

Minnesota has several product stewardship laws for paint and electronics and has been a leader in

product stewardship efforts. Other states such as Maine, Colorado, Oregon, and California have adopted

extensive EPR programs from which we can learn.

Goals and policies

The following goals and policies provide the basis for improving solid waste management in the TCMA.

For the purposes of this section, “goal” is defined as a desired result; “policy” is defined as a course of

action adopted by a government, party, business, or individual.

Goal 1: Protect and conserve. Manage materials in a manner that will protect the environment and

public health, reduce GHGe, conserve energy and natural resources, and reduce toxicity and exposure

to toxics.

The goal of the WMA is to protect Minnesota’s land, air, water, and other natural resources, and public

health by improving waste management to serve the following purposes: reduce the amount and

toxicity of waste generated; increase the separation and recovery of materials and energy from waste;

and coordinate the statewide management of solid waste and the development and financial security of

waste management facilities, including disposal facilities. This goal recognizes a prevention-based

approach to waste management to reduce, to the extent feasible, adverse effects on human health and

the environment.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

8

Policy 1: Challenge current waste management practices to identify materials with opportunities

for management methods that fall higher on the waste hierarchy.

Policy 2: Focus on reuse and prevention. Apply SMM framework to decision making to decrease

the environmental impact. Hold manufacturers responsible to design for repair, reuse, and

recyclability.

Policy 3: Support and strengthen reuse and recycling markets to increase demand for reusables

and recyclables.

Policy 4: Ensure systems are in place that foster the growth of organics recovery.

Policy 5: Promote recovery of energy when disposing of waste through WTE.

Policy 6: Strengthen compliance with cornerstone environmental statutes.

Policy 7: Increase public participation in decisions that impact them with special emphasis on

Environmental Justice.

Policy 8: Account for all phases of a material’s life cycle, including environmental and economic

impacts.

Policy 9: Reduce toxicity by working with manufacturers to eliminate the use of hazardous

components in packaging and products.

Goal 2: Whether public or private, hold all members of the solid waste system accountable for

meeting the goals of this MPP.

To achieve the aggressive goals established in this MPP and by the Legislature, all parties in the solid

waste system must be held accountable, and the MPCA must provide oversight of the system. Cities and

counties must ensure the systems are in place for the proper management of waste, emphasizing

managing it higher on the hierarchy. Generators must use the tools provided to properly manage the

waste they create and to reduce the amount of waste created. Haulers and facility operators must

ensure that waste is managed properly upon collection and look for opportunities to shift materials up

the hierarchy.

Policy 10: Support the collection of reliable data to ensure that all parties in the solid waste

system accurately measure progress toward achieving the objectives of this MPP.

Policy 11: Ensure that demolition debris and industrial wastes are categorized and are managed

according to the applicable Statutes and Rules. Measure more accurately the composition of

non-MMSW generated in the TCMA and being landfilled in Minnesota.

Policy 12: Increase opportunities for cities to implement organized collection for recycling and

MMSW.

Policy 13: Cities and counties hold haulers and businesses in their communities accountable for

managing waste according to the MPP via their licensing agreements.

Policy 14: The MPCA provides oversight of the system by holding counties and private

businesses accountable. The Legislature holds the MPCA accountable for meeting waste

management goals.

Policy 15: Hold producers responsible for the treatment or disposal of post-consumer products.

Policy 16: Set goals and performance standards following consultation with stakeholders on

product stewardship.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

9

Goal 3: Systematically and steadily promote more regional cohesiveness and collaboration to foster a

synergistic, regional approach.

To achieve our goals of reducing the amount of solid waste generated and recycling/composting 75% of

our solid waste by 2030, it is imperative that the counties work in concert and avoid duplication of

efforts. This includes consistent uniform ordinances, greater collaboration between staff and leaders in

each of the seven metro counties, and planning for facilities through a regional lens.

Policy 17: Develop model ordinances that could be enacted by all counties.

Policy 18: Local governments work together to develop a consistent ordinance structure that

allows private entities to smoothly operate across the region.

Policy 19: Promote efficiencies and cost effectiveness and reduce environmental costs in the

delivery of integrated solid waste management services.

Policy 20: Assure elected county officials understand the importance of supporting and

maintaining WTE facilities.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

10

Part three: MPP 2022-2042

The MPP provides guidance to all stakeholders responsible for TCMA solid waste management and was

developed in accordance with the requirements of Minn. Stat. § 473.149, subd. 2d. for a land disposal

abatement plan. It describes broad regional system objectives, a landfill diversion goal, and the

strategies necessary for solid waste programs and services to meet the region’s needs for the next 20

years. The MPP recognizes the inter-county complexity of the TCMA solid waste system and the value of

and need for regional approaches. Specific details associated with implementing the MPP on a local level

will be refined in the CSWMPs and any regional plan developed by the metropolitan counties. The MPP

identifies where specific stakeholder actions are necessary to implement the objectives and strategies.

The MPP:

1. Places emphasis on the upper end of the hierarchy (waste reduction, reuse, recycling, and organics

recovery).

2. Establishes objectives for each waste management method.

3. Achieves full use of resource recovery facility capacity and implements the Restriction on Disposal

(ROD) of MMSW requirements.

4. Establishes a goal to minimize the amount of metro MMSW land disposal that will occur.

The MPP includes numerous strategies for reducing waste and increasing recycling and organics

recovery. All stakeholders in the system have roles and responsibilities to ensure successful

implementation of these strategies. A table that identifies each strategy is provided in Appendix G.

Regional waste generation forecast

In 2021, the TCMA generated 3.3 million tons of MMSW. Metro MMSW generation is forecasted to

grow to 3.92 million tons by 2042 (see Figure 3). The figure also includes the 15% reduction strategy to

help visualize the intent of source reduction. Achieving a 15% reduction from the forecast amount will

require waste generation to remain equal to the current generation going forward. This forecast does

not include the non-MMSW waste stream (i.e., construction, demolition, and industrial wastes). The

MMSW forecast was generated using waste generation amounts from 2010-2021. This period was

chosen because the 2007-2009 recession created a new baseline.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

11

Figure 3. Total MSW Generation Forecast with the 15% source reduction objective

Non-MSW like demolition debris, contaminated soil, and industrial waste continues to experience

growth in generation of industrial and demolition debris (see Figure 4). It is forecasted that annual

generation of non-MSW will increase by 6,000,000 cubic yards over the next 18 years. Reduction of non-

MSW is vital to reach environmental goals in the future. Ash generation is forecasted to remain

consistent over the next 20 years. Reducing or ceasing operations at Hennepin Energy Recovery Center

could lower the amount of ash being land disposed but would greatly increase the need for MMSW

disposal over the life of the plan.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

12

Figure 4. Non-MSW and Ash Forecast

Sustainable Materials Management (SMM)

SMM overview

SMM identifies the best use and management of materials, considering the environmental impacts

throughout the life cycle of materials. The major stages in a material's lifecycle are:

• Raw materials extraction

• Product manufacturing

• Product use

• Transportation

• End of life management

To protect the environment and human health, an understanding of “waste” must broaden. The impact

of materials and waste include GHG emissions, pollution to land, air, and water, and resource depletion.

These impacts happen throughout the entire life cycle of a product. All phases of that cycle must be

considered, not simply end of life.

SMM includes traditional solid waste management. Management of the upstream impact of materials

and the toxic chemicals used to manufacture those materials are also considered. The MPCA and EPA

concede that an SMM approach seeks to:

• Use materials in the most productive way with an emphasis on using less.

• Reduce toxic chemicals and environmental impacts throughout the material life cycle.

• Ensure we have sufficient resources to meet today’s needs and those of the future.

An SMM approach invites more interested parties involved throughout the life cycle of a product to

provide perspective and provide a broader scope of impact. These potential partners include, but are

not limited to, primary chemical formulators, academic researchers, brand owners, retailers, product

designers, and consumers.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

13

Life Cycle Assessment

SMM uses Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to inform decision-making. LCA is a way to model the

environmental impacts associated with a material or process from resource extraction through end-of-

life management. This yields information on environmental impact indicators, such as GHGe, toxicity,

and acidification. These metrics help policymakers focus efforts on high leverage opportunities. At this

time, the most widely used environmental indicator is GHGe. According to the EPA, materials can

account for up to 42% of GHGe in the U.S. Most of that impact happens in the production lifecycle

phase. In alignment with the waste hierarchy, the least environmentally impact action is to produce and

use less.

Figure 5. LCA: a methodology for modeling the environmental impacts of a material or product from raw

material extraction through end-of-life management

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

14

LCA modeling can compare environmental impacts associated with one material versus another. LCA

modeling can also compare the impact of different management methods of the same material.

Designers and manufacturers can use LCA modeling to determine the life cycle phase(s) in their

products’ lifecycle with the greatest specific impacts (e.g., water, air, and human health). For instance,

electronics manufacturers may find that the use phase impacts are the energy usage by the consumer.

The manufacturer can design the product to use less energy. They could also design the product to last

longer and be reparable by producing replacement parts.

The ability to track and report on the environmental impacts of our materials management system is

critical. Measuring repair activities as a waste reduction activity will be important to support this

activity.

SMM for recycling

If Minnesotans recycled and composted all waste, GHGe would be reduced by only 3%. Recycling is

important but recycling alone is insufficient. Moreover, material attributes like recyclability do not

necessarily correlate with the greatest reduced environmental impacts. It is important to keep in mind

that if something is marketed as “compostable” or “recyclable” that does not necessarily mean that it

provides the best environmental outcome. For example, a steel coffee can is recyclable, so it may seem

like the best packaging choice. LCA modeling comparing steel cans to other coffee packaging types

shows that is not the case. Foil pouches result in fewer GHGe, despite having no material end market.

That said, recycling plays an important role in the waste management system. If light weight packaging

brings the greater environmental benefit, we should support developing recycling markets for packaging

like foil pouches. Volatile recycling markets require innovative solutions to remain relevant.

SMM tends to favor prevention and reuse yet also reaffirms the importance of recycling. Recycling is

commonly lauded for its ability to decrease demand for landfilling. However, there is a greater

demonstrated environmental benefit in recycling when the byproduct alleviates the need to extract

virgin materials by mining. The environmental degradation from extraction, energy use during

processing, and transportation often tip the scales in favor of recycling. Identifying the highest and best

use for each material is the primary consideration under this framework.

SMM and toxicity

Using an SMM approach also sheds new light on the use of toxic chemicals in manufactured materials.

The policy and purpose of the Waste Management Act calls for a reduction in the toxicity of waste

generated. Reducing toxics in the products we purchase reduces the overall toxicity of waste generated.

In the past, the State of Minnesota Office of State Procurement prioritized recycled-content products on

merit of recycled content alone. For example, a problem with the statewide flooring contract emerged

when the vinyl flooring with recycled content was found to contain legacy heavy metals. The contract

now restricts recycled content containing resilient flooring products unless they are third-party certified

to conform with NSF/ANSI Standard 332: Sustainable Assessment of Resilient Floor Covering. This

highlights the need to look at all material properties, not just recyclability.

Solid waste abatement objectives

Tables 1 and 2 set specific quantifiable objectives for abating the need for and practice of land disposal

for the TCMA region over the next 20 years, pursuant to Minn. Stat. § 473.149, subd. 2d. Landfill

abatement is best achieved through an integrated solid waste management and SMM approach.

Therefore, the statute requires “objectives for waste reduction and measurable objectives for local

abatement of solid waste through resource recovery, recycling, and source separation programs.”

Table 1 defines the waste reduction objectives by percentage and tons reduced from forecast

expectations. The forecasted trend in waste generation accounts for much of the reduction that

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

15

currently is occurring such as light weighting of materials. This plan calls for a 15% improvement on that

trend-line following many comments that state that the waste reduction goal needs to be much more

aggressive.

Table 2 defines the objectives by percentages of waste generated, and Table 3 defines the objectives in

tons. Table 3 shows the objectives in tons based on the current waste forecast in this MPP and is subject

to change if the forecast is updated. Several factors were considered when setting the objectives,

including:

• Current statutory goals

• The regional waste forecast highlighted at the beginning of Section 3.

• Metro counties will achieve the 75% recycling rate as laid out in Minn. Stat. § 115A.551 by 2030.

• Total compliance with Restriction on Disposal (ROD) is assumed.

• Additional capacity at any given WTE facility will be used regardless of originating county

for MMSW.

• Landfilling is assumed to be a minimum of 5% given the need to manage non-processible waste,

bulky items at WTE facilities, and residuals and rejects from recycling and composting facilities.

• Baseline is the last year of observable data (2021) since the latest year of data represent the

best data available to the counties and their current education and diversion practices.

Currently, Hennepin County is the sole provider of MMSW to the Hennepin Energy Recovery Center

(HERC) facility while Ramsey and Washington split the capacity of the Ramsey-Washington Energy

Center. Each of these facilities is assumed to be at capacity due to ROD compliance. Dakota County will

continue to send MMSW to the Red Wing processing facility, estimating 10,000 tons in 2020 and 13,000

tons in all subsequent years.

Meeting the objectives will reduce GHGe, conserve resources, reduce land disposal, and recover

energy. The goals for recycling, organics, WTE, and landfilling do not change after 2030. The 75%

recycling goal will be difficult to reach, so it will remain a relevant target beyond 2030. To continuing

making progress, it is prudent to widen our regional focus to include waste reduction, given that the

greatest environmental gains occur through reducing waste. Reduced upstream impacts contribute to a

common goal with the recycling rate. The Hennepin County Board recently issued a resolution to create

a plan for closing the Hennepin Energy Recovery Center sometime between 2028 and 2040. Due to the

uncertain timeline, the MPCA is not revising the assumptions in the objective tables. However, history

shows that the closure of a WTE facility leads to increased landfilling. MPCA expects that currently

projected waste going to HERC would go to landfills if the facility closes. A robust plan to divert

additional material and an influx of resources to improve programs and infrastructure may reduce the

volume of waste that would be landfilled if HERC is closed. Without aggressive programs to replace

HERC an additional 365,000 tons of material would be landfilled per year, which is equivalent to the

largest landfill in Minnesota.

Table 1. Waste reduction system objectives in percentages and tons (2021-2042)

Management method

Current system (2021)

2025

2030

2036

2042

Waste Reduction

0%

2.9%

6.4%

10.7%

15.0%

Waste Reduction Tons

0

98,577

231,557

403,919

587,984

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

16

Table 2. MMSW management system objectives in percentages (2021-2042)

Management method

Current system

(2021)

2025

2030

2036

2042

Recycling

28.6%

36.9%

47.4%

47.4%

47.4%

Organics

16.6%

21.5%

27.6%

27.6%

27.6%

WTE

21.4%

24.0%

20.0%

20.0%

20.0%

Landfill

33.4%

17.6%

5.0%

5.0%

5.0%

The table above shows the percentages of how waste is managed currently and projections for future

years. The data under 2021 is from the latest SCORE report. Projections are based on the assumptions

found in Appendix F.

Table 3. MMSW management system tonnages (Based on objectives in Table 2 in thousands of tons [2010-

2030])

Management method

Current system (2021)

2025

2030

2036

2042

Recycling

944,968

1,237,436

1,598,496

1,596,691

1,580,830

Organics

547,931

719,166

929,331

927,801

918,102

WTE

707,268

828,000

674,087

673,198

666,382

Landfill

1,102,165

567,014

168,522

168,299

166,595

Total

3,302,332

3,351,615

3,370,437

3,368,899

3,331,909

The table above shows the same data and projections in thousands of tons to give context to the

percentages in Table 3 and illustrates the amount of waste that needs to be managed in the TCMA.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

17

Figure 6. TCMA MMSW management methods: past, present, and projection (SCORE and Certification Reports)

Evaluation of the system objectives

The MPCA will evaluate progress toward achieving all the system objectives through the annual SCORE

Report submitted by the counties every April. The MPCA recognizes the challenges associated with

measuring progress and measurement in general. Measuring waste reduction has posed challenges for

years. See the

Environmental impact target section for a discourse on a more robust way to measure

environmental impact. Using data the counties currently provide, the MPCA has begun to calculate the

environmental impact in the annual SCORE report. MPCA intends to continue to improve those efforts

to better quantify the impacts of county programs on the environment. The environmental impact

target does not require the counties to submit additional information to the MPCA. The MPCA will

continue to work with local governments, haulers, and others to assure the data collected is necessary

and relevant and will continue to collect data on a statewide and regional basis. The MPCA has historically

used the SCORE Report as the method of tracking annual progress toward the objectives and has used the

Solid Waste Policy Report to recommend needed policy changes to the legislature.

Emphasis on the upper end of the hierarchy

Handling materials using methods on the upper end of the hierarchy should be measured and reported.

This includes an emphasis on waste reduction and reuse. There has been an emphasis on the legislative

recycling goals, and while recycling plays an important role in the waste management system,

measurement of success should be based on all impactful efforts. Reduction and prevention need to be

organized and implemented through the TCMA.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

18

Aggressive objectives for waste reduction and reuse, recycling, and organics

recovery

All stakeholders, including the MPCA, will be held accountable for meeting these objectives. The MPCA

believes the objectives are achievable, but to reach them, the TCMA will need new tools, enhanced

infrastructure, and increases in funding. The current rate of increases in recycling and compost will not

get the TCMA to the 75% recycling objective. New approaches to meeting the goal and other objectives

in the MPP are needed for environmental protection.

Waste reduction and reuse

According to the EPA, waste prevention is the most environmentally preferred strategy to reduce

impacts. Waste reduction and reuse methods are the most effective waste prevention strategies.

Meeting waste reduction and reuse objectives will reduce the amount of MMSW that needs to be

managed. Forecasting the projected MMSW generation for each county will deduct the tons of material

reduced or reused.

Benefits of achieving success

In 2021, the TCMA achieved a 45.2% combined rate for traditional recycling and organics diversion.

Minnesota would benefit from exploring additional methods to achieve the intended environmental and

human health outcomes of the 75% recycling goal. Environmental and human health impacts of

management methods should be considered. Minnesota needs to modernize data collection,

measurement, and reporting. Other priorities should include identifying the highest return on

investments in how staff time is allocated, introducing the most impactful policy changes, and investing

in strategic infrastructure needs.

Oftentimes, waste reduction and reuse efforts can be cheaper than handling the same materials as

waste. Incentivizing and tracking waste reduction and reuse separately ensures that county partners

receive recognition for those efforts. Some counties have reported prevention and reuse in their

CSWMPs and programming. Historically, reuse activities have counted towards the recycling rate via

SCORE reporting.

An analysis of the 2018 SCORE report “recycling” data for accuracy revealed that, statewide, 79 of 87

counties reported reuse activities. This illustrates the need for counties to be recognized for investing in

reuse. In response, the MPCA modified the 2021 SCORE reporting form to track reuse activities.

Prevention and reuse programming result in fewer emissions. They are not and should not be treated as

equal to recycling. The state should transition to a reporting structure that documents the increased

climate and other pollution reductions from handling materials using methods higher on the waste

management hierarchy.

Environmental impact target

To prioritize waste reduction and solid waste management with environmental and human health

benefits, MPCA is setting an environmental impact target for TCMA counties based on full LCA. Under

this environmental impact target, weight-based accounting for waste reduction, reuse, recycling, WTE,

and landfill disposal is translated into GHGe generated or avoided. In this way, counties still report and

work to meet their 75% recycling rate goal, but the environmental impact target documents overall

changes in GHGe based on all county efforts and programming. By tracking progress with GHGe

(currently the most accessible proxy for environmental impact), in addition to the recycling rate,

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

19

counties can invest in upstream activities, report on those efforts, and reach their environmental impact

target through waste reduction and reuse programming as well.

The environmental impact target is defined by calculating the emissions avoided if the county were to

reach the materials management goals set forth in the Metro Policy Plan by 2030. This means totaling

the emissions associated with:

• Achieving a 15% waste reduction goal.

• Achieving a 75% recycling rate goal as established by the Minnesota Legislature.

• Achieving complete compliance with Restriction on Disposal, resulting in WTE facilities capturing

most of the remaining materials.

• A minimum of 5% of material sent to landfill.

The value of setting a comprehensive environmental impact target that counts emissions reduction from

the entire materials management system as all strategies become opportunities for meeting the target.

This means a county can choose to do more waste reduction or reuse to reduce their GHGe more

significantly and progress further on meeting their environmental impact, than solely focusing on

recycling to achieve their 75% recycling rate. If a county is already meeting or exceeding their

environmental target, the MPCA would recommend adjusting their target to be more ambitious and

support continued work on reducing impacts from materials being handled. County-specific calculations

will be made using 2021 SCORE data.

Each county will be able to work with their MPCA Planner to review their current progress and identify

options for meeting their environmental impact target, determining which programs will have the

greatest benefit. For example, counties will be able to see how the amount of emissions reduction

achievable by focusing on food rescue versus composting. The target will not replace the 75% recycling

goal already in statute.

The following example, using data from Scott County, illustrates how the environmental impact target

will be implemented and shows two potential scenarios. In the first scenario, Scott County meets the

75% recycling rate goal by 2030 as required by the Minnesota Legislature. The rest of their materials are

handled business-as-usual, meaning the county didn’t implement additional waste reduction, reuse, or

WTE strategies. The total GHGe savings is 234,037 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (mtCO

2

e).

In the second scenario Scott County maintains their current 55% recycling rate until 2030. However,

they invest in waste reduction strategies and reduce materials by 10%. The county accomplished this by

focusing on preventing food from going to waste, reducing paper use, and eliminating a small number of

single-use items and replacing them with durable reusable systems. The total GHGe savings is 224,060

mtCO

2

e. In the second scenario, only 10% of the waste is being source reduced. Yet, compared to a 20%

increase in recycling in the first scenario, the amount of GHGe is very similar. How materials are

managed makes a big difference. Scott County can achieve nearly twice the environmental and human

health benefit by reducing materials than recycling in this scenario. This affirms the waste management

hierarchy and emphasizes the importance of first reducing, then reusing, and then continuing to manage

materials down the hierarchy as needed if the first two strategies are not feasible.

The MPCA staff will work with counties to assess their options for meeting the environmental impact

target using an interactive tool based on EPA’s WARM. The MPCA will be able to model county-specific

scenarios for materials management using data that the counties currently provide. The MPCA will not

be requesting additional information from the counties to track this new goal.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

20

Figure 7. Carbon emissions impact of different management types

Strategies and best management practices to achieve the objectives of the MPP

There are various approaches to meet the system objectives of this MPP. The TCMA waste management

system is governed by multiple public and private entities, and a variety of strategies provide the

flexibility to meet the needs of each program or situation. The state, counties, cities, businesses,

nonprofits, communities, and residents all have specific roles and responsibilities for improving solid

waste management. To minimize conflicts and inefficiencies, it is important to select strategies that

align public and private objectives, to work together to identify necessary changes to existing strategies,

and to indicate where new strategies are needed. Counties can proposal alternative strategies if they

see fit. Proposals must achieve comparable objectives and will be subject to agency approval. The point

value of alternative optional strategies will be determined by the MPCA. Many of these strategies will

require investment and additional funding. The MPCA will advocate for additional funding for the

system when appropriate and asks the counties to do the same.

County solid waste plan evaluation point structure

Each topic below includes key strategies that will be instrumental to reaching the objectives of this MPP.

Certain strategies are required to be incorporated into CSWMP. Optional strategies are assigned a point

value. The counties will pick from any of the optional strategies to reach a minimum of 75 points.

The strategies are weighted by difficulty and by management strategy in accordance with the Waste

Management Hierarchy. This places an incentive on environmental and human health outcomes while

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

21

allowing counties the flexibility to design and adapt their solid waste programs. The various optional

strategies are worth 4-9 points. The optional strategy point total is 194 points, and the counties must

have a minimum of 75 points for their CSWMP to be approved. Appendix G houses a strategy

spreadsheet for counties to use in designing their solid waste plan.

Costs implications of strategies should be estimated by county staff when considering feasibility of

implementation. The MPCA is committed to achieving the objectives established in this MPP and intends

to assist with strategy implementation as noted below.

Improving the reliability of the data

The MPCA strategic plan calls for the Agency to “accelerate the availability of data and information in a

self-service format.” From a solid waste perspective, one of the best ways to accomplished this is to

ensure that data is consistently collected through the most reliable sources and that all waste and waste

reduction be tracked. The MPCA and the counties have historically focused on only MMSW. Little

attention has been directed toward the measurement of demolition debris and industrial waste (ISW).

The SCORE program created a strong framework for tracking progress toward the goals and objectives

of the WMA. Over the past 30 years, there have been some problems identified with traditional

measurement methods. Like the MPCA and counties, SCORE historically focused on only MMSW, with

no data on ISW reported or requested. In addition, the success of county programs has been measured

through a weight-based system that treats all material tons equally.

Our improved ability to understand the environmental and human health impact of different material

types has exposed the limitations of weight-based measures. Weight-based measures are important but

have limitations. Data analysis can be enhanced by collecting additional data in addition to the weight-

based measures. A moving target of what counts as recycling has added to inconsistencies. In recent

years, yard waste and compost have been added to the recycling side of the ledger.

Ultimately, a large focus has been placed on recycling in county programs to the detriment of waste

reduction and reuse. As discussed above, the greatest environmental and human health benefits are not

realized through recycling. Improved reporting provides the information needed to understand how to

achieve better environmental and human health outcomes. The added reuse component to the SCORE

report captures the reuse activities within counties. The intended outcome is to fill a data gap that has

existed since the inception of the program in the early 1990s. Hauler reporting requirements were

added in 2016, but inconsistent compliance from the haulers, inconsistent support from counties, and

staffing issues at the MPCA have led to lax enforcement and limited follow-up.

As previously mentioned, SCORE is only focused on MMSW, with no requirements to track other waste

streams. Landfills report amounts of demolition debris and industrial waste annually. Yet, there is

limited data regarding recycling rates of those two material streams. We also have limited data about

non-MMSW landfill diversion such as recycling. To improve the management of non-MMSW materials, it

is critical to have a better reporting for this waste sector. Despite these challenges, there are several

strategies that can be pursued that will improve the management of data in the TCMA.

Required strategy:

The strategy listed below is required to be incorporated into the CSWMP because it is relatively simple

or has significant environmental benefit.

1. Increase compliance with hauler reporting per Minn. Stat. § 115A.93. Compliance with hauler

reporting in metro counties has been mediocre. In 2021, these compliance rates were between 45%

and 68%, within the TCMA. There are several challenges regarding the compliance numbers. Some

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

22

haulers may be misreporting to counties. In these cases, counties should hold haulers accountable

for completing their reporting accurately. Reliable hauler reporting provides a benchmark for the

objectives of this MPP. Hauler reporting is a shared responsibility for the state and county.

Cooperation from counties to maintain accurate license lists will allow the MPCA to trust the

information collected. Both the state and counties benefit from the collection of this data. Sharing in

the responsibility ensures accuracy and efficiency. Best practices in the promotion of compliance

with hauler reporting include:

• Sending quarterly reminders to all licensed haulers

• Reviewing submitted data in ReTRAC

• Active communication and follow-up regarding incorrect or missing hauler data

• Requiring proof of data submittal prior to license renewal

• Cleaning up the regional license data to ensure that haulers are truly operating in the

counties

Improved compliance and data integrity would facilitate the mapping of waste flow in the TCMA

from origin point to end destination. We need to understand the breakdown of residential and

commercial tonnage and the scope of material exports. Dakota County demonstrates that

improving compliance with the haulers is possible when county staff are persistent. Compliance

rates for haulers in Dakota County is 68%, compared to 45-55% in other counties in the metro.

2. Provide required county reporting. Ensure the MPCA receives all data in the state-issued format.

Counties should collaborate on creating best data practices for soliciting data from organizations.

The MPCA and counties shall standardize waste composition sorts for consistency. SCORE,

certification, and the metro county annual reports are also targeted in this strategy.

3. Require waste composition study at least once every 5 years at all landfills that are located within

your county. Waste composition study data helps identify important trends on waste types and

quantities. Landfill information will help policy, planning, and implementation, such as assessing

capture rates. Counties with landfills receiving TCMA waste should introduce an ordinance to

reinforce this requirement. Waste composition studies shall include MMSW, ISW, and demolition

debris disposal streams. The MPCA seeks to assure all landfills receiving metro waste operate with

equal requirements. Dakota County ordinance no. 110 establishes a requirement for waste

composition studies to be performed every five years at all land disposal solid waste facilities.

Performing waste composition studies on a regular schedule will help determine generation rates,

aid in capture rates, and provide material type breakdown.

Optional strategy:

The following strategy is optional and may be incorporated into a CSWMP. Each strategy has been

assigned a point value, which is added to the total amount of points the county must achieve for

approval of their CSWMP by the MPCA.

4. Improve recycling data collection at businesses within the county.

Point Value: 7

Commercial buildings required to recycle in Minn. Stat. § 115A.151 should report their recycling

tonnages to the county in which business is conducted. Exempted businesses can provide

documentation of their licensed hauler's reports to the MPCA. Develop an ordinance that requires

businesses to assign a recycling manager. The recycling manager shall report weight, material type,

and management method for self-hauling. Self-hauling shall include contracted services outside of

licensed haulers. Alternative to development of an ordinance would be developing a surveying

approach. Create a survey method resulting in a statistically significant number of annual responses.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

23

Review and analyze to assure reliable commercial data are being collected. Carver County conducts

an annual survey of businesses to collect data from generators who self-haul. Replicating this

approach would fulfill this strategy.

State-led strategies:

The following strategies are the responsibility of the MPCA and will support the efforts by the counties.

5. Require waste composition study at all landfills. Understanding the composition of MMSW,

demolition debris, and ISW streams is critical to perform GHG calculations and to quantify other

environmental impacts. Resource recovery facilities are currently required to conduct waste

composition studies every five years. This requirement should be extended to all disposal facilities

for consistency and equal treatment, and to have comparable information from the data. Waste

composition study data provides important trend information on waste types and quantities. The

addition of landfill information will help policy, planning, and implementation efforts, such as

assessing capture rates. The State will work to require waste compositions across the state with the

express purpose of obtaining better data.

6. Develop appropriate and consistent waste reporting systems to measure all waste. Measuring and

reporting all waste (including MMSW, demolition debris, and ISW) through annual reporting is

necessary for the state and counties to effectively manage waste to its highest and best use.

Alternative measures to weight-based reporting that encompass the environmental impacts of a

material should be researched and considered. This could include using SMM tools such as capture

rates and human health impact data that focus more on the impact of a material throughout its life

cycle. The MPCA will continue to build on initial efforts to report on the environmental and human

health impacts utilizing the data that counties currently submit. High quality data will result in the

development of strong statewide policy. Developing a system will support evidence-based decision

making for future laws, policies, rules, and program planning. Commonly recovered materials from

demolition sites are concrete, shingles, wallboard, carpet, and lumber. A robust system for

evaluating these materials will help counties and the state prioritize our efforts.

7. Continue to explore options for growing the agency’s LCA data, modeling, and resources to better

support counties in measuring and tracking environmental and human health impacts. This

includes translating county solid waste measures from weight-based measures to GHGe and other

environmental and human health impacts and periodically updating the state’s consumption-based

emissions inventory to complement the current in-boundary emissions inventory. It also includes

incorporating environmental impact data across agency materials management and solid waste

management programs to identify priority materials and strategies to target the highest-impact

categories.

8. Continue to engage with counties in the development of an environmental target that better

accounts for and incentivizes programming and actions higher on the hierarchy. The recycling rate

serves a specific purpose and there is an opportunity for the MPCA to evaluate and develop an

approach to represent county SMM efforts more holistically.

Regional solutions

The TCMA counties do not have a formal regional waste management district. Yet, it is practical to

implement certain strategies at the regional level. Collaboratively designing and modernizing a materials

management system will benefit all TCMA counties.

Required strategies:

The strategies listed below are required to be incorporated into the CSWMP because they are relatively

simple or have significant environmental benefit.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

24

9. Participate in an annual joint commissioner/staff meeting on solid waste. This annual or semi-

annual meeting will provide an opportunity to get a county commissioner and lead staff from all

seven counties together to discuss relevant waste topics. The purpose of this strategy is to help

ensure that all seven county boards understand the challenges that each county faces, learn from

the CSWMP of other counties, and examine places to collaborate to meet the regions solid waste

goals. MPCA will take the lead in organizing this meeting at the inception.

10. Commit to standardized outreach and education. The seven counties in the TCMA must coordinate

on their recycling messaging to avoid confusion among residents. To coordinate, each county should

attend the Recycling Education Committee (REC) meetings and use REC communications calendars.

If a deviation is made from the REC materials, the TCMA counties all must agree. Counties should

utilize or adapt the MPCA-designed library exhibits on food storage tips and the impacts of food

choices to educate residents on preventing food waste. To create regional consistency, counties

should acknowledge organics recycling and food scraps are both in use in different areas of the

TCMA. Counties should coordinate to reduce confusion associated with the use of different

terminology within the region. Outreach and education efforts should include how to handle

materials not accepted in curbside collection bins. These materials should include lithium-ion

batteries, scrap metal, and other materials accepted by environmental centers and household

hazardous waste drop-off sites.

11. Engage in efficient and value-added infrastructure planning. TCMA counties should seek to

eliminate system redundancy by sharing and co-developing CSWMP for managing all material types.

This collaboration includes the use of emerging technologies that have the potential to reduce or

manage waste higher on the waste hierarchy and that have the potential to impact materials and

processes that have a greater environmental impact. TCMA counties should foster a space for

counties and private partners to work cooperatively and not competitively to build system

resiliency. More processing capacity to assure materials with useful life are routed appropriately is

imperative. Food-derived composting and food rescue are high priorities for infrastructure planning.

MRFs face pressing issues such as overflow of materials and a need for fire suppression.

12. Develop plans for large facility closures to reduce landfill reliance. The plans must include:

• Develop a plan that identifies alternatives that can manage the waste currently managed at

the facility. This plan must include landfills, transfer station infrastructure, recycling and

composting infrastructure and other logistical solutions to manage MMSW.

• Identify a plan to push waste up the hierarchy including an effort to prioritize reduction.

• Issue a letter assuring waste to one or more of the alternative locations suitable as part of

the CON process for landfill expansions when necessary.

• Include in the plan acknowledgement of liability associated with increased landfilling

including the understanding that at some point in the future the county may be identified as

a responsible party for a superfund clean-up investigation.

• Identify and evaluate potential locations within the county or region for a disposal facility

that can be developed within the timeline of the facility closure.

• Any new facilities that are sited should take clear and effective measure to ensure

that they are not located in environmental justice areas.

• A list of policy, program, infrastructure changes needed to eliminate reliance on WTE and/or

landfilling.

• Consideration of where money saved by closing the facility could be reinvested to benefit

the region.

Metropolitan Solid Waste Management Policy Plan 2022-2042 • January 2024 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

25

Waste reduction

In accordance with Rule 9215.0580 and Minn. Stat. § 115A.02, counties are responsible for advancing

prevention and reuse along with other solid waste management strategies. Waste reduction means not

generating any materials that require further recycling, composting, disposal, or other management.

Waste reduction includes reducing the amount and toxicity of materials generated. It is at the top of the

hierarchy, because it is the best option for the environment. Using an SMM framework, counties can

design programs that direct limited resources toward waste reduction programming and infrastructure