A Changing Rate Environment

Challenges Bank Interest Rate Risk Management

Interest rate risk is fundamental to the

business of banking. Changes in interest

rates can expose an institution to adverse

shifts in the level of net interest income

or other rate-sensitive income sources

and impair the underlying value of its

assets and liabilities. Examiners review

an insured institution’s interest rate risk

exposure and the adequacy and effec-

tiveness of its interest rate risk manage-

ment as a component of the supervisory

process. Examiners consider the

strength of the institution’s interest

rate risk measurement and manage-

ment program and conduct a review

in light of that institution’s risk profile,

earnings, and capital levels. When a

review reveals material weaknesses in

risk management processes or a level

of exposure to interest rate risk that is

high relative to capital or earnings, a

remedial response can be required.

In today’s changing rate environment,

bank supervisors are monitoring indus-

try balance sheet and income state-

ment trends to assess the industry’s

overall exposure to and management of

interest rate risk. This article reviews

the current interest rate environment,

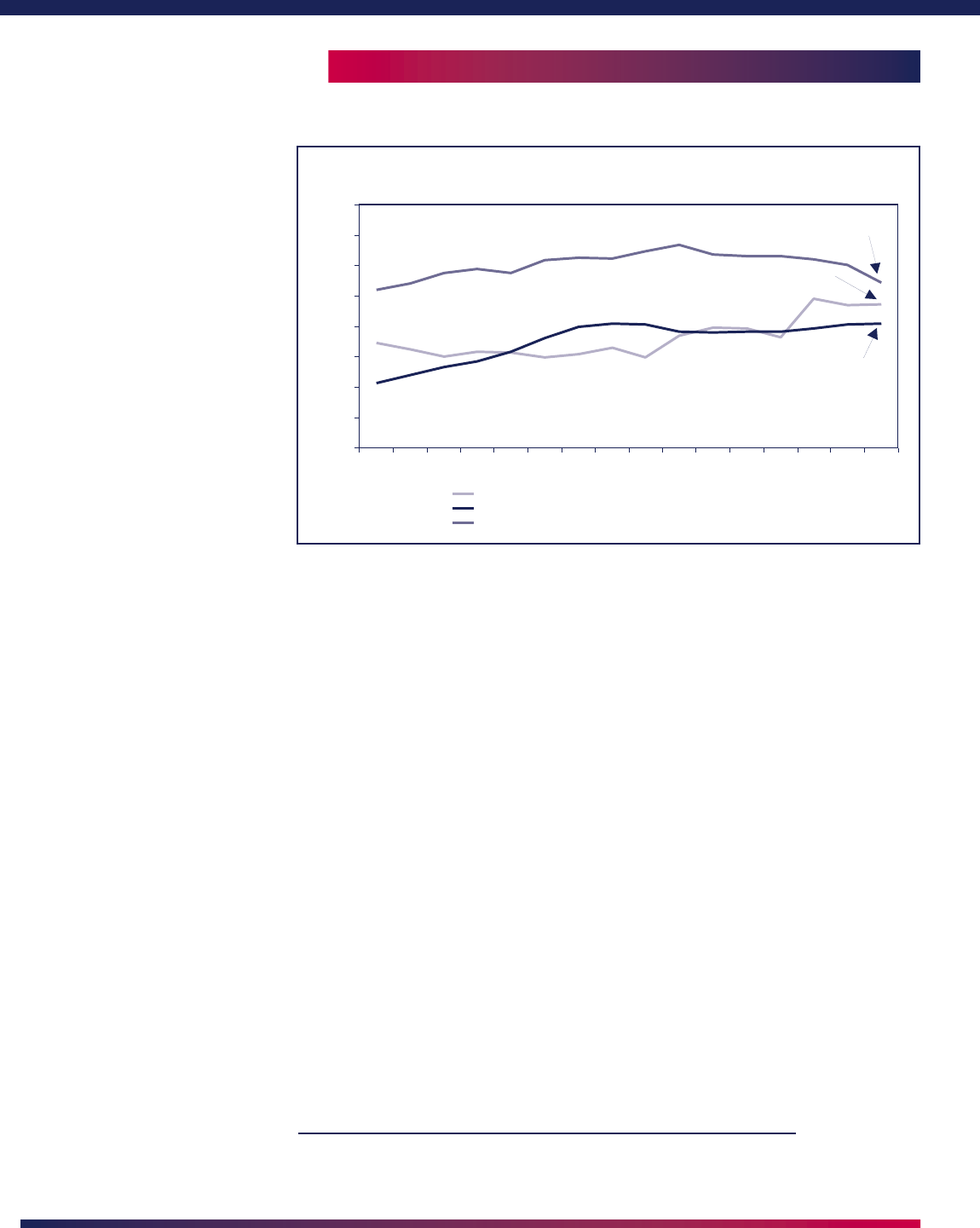

Chart 1

discusses potential risks associated

with a rising rate environment and a

continued flattening of the yield curve,

and analyzes banking industry aggre-

gate balance sheet information and

trends. It also reviews findings from

recent bank examination reports in

which interest rate risk or related

management practices raised concern

and highlights common weaknesses in

risk management, measurement, and

modeling practices.

The Current Rate

Environment

Since the 1980s, and despite upward

rate spikes in 1994 and 2000, the level

of interest rates has generally been

declining (see Chart 1). In September

1981, the rate on the 10-year Treasury

bond reached a high of over 15 percent;

it has since declined to a low of just over

3 percent in June 2003. During roughly

the same period, other rate indices

also fell in generally the same manner,

though not always in tandem. For exam-

ple, the Federal funds rate fell from

over 19 percent to 1 percent, and the

Short-Term Rates Are Turning Up from Historic Lows

Rates

May 2005

1976 1980 1984 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004

30-Year Mortgage

10-Year Treasury Fed Funds

Source: FDIC

20%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

Fed funds, 10-year

Treasury, and 30-year

mortgage rates hit

highs in 1981

Fed funds rate

begins ratcheting

upward without

equal increases in

longer-term rates

5.75%

4.28%

3.00%

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

5

Interest Rate Risk

continued from pg. 5

30-year mortgage rate average peaked

at over 18 percent and dropped to under

6 percent.

During the past 12 months, however,

the banking industry has sustained a

well-forecasted series of “measured”

increases to the target Federal funds

rate. Since June 2004, the Federal

Open Market Committee (FOMC) has

steadily increased the intended Federal

funds rate in moderate 25 basis point

increments to its current level of 3

percent. Generally, changes in the

Federal funds rate will affect other

short-term interest rates (e.g., bank

prime rates), foreign exchange rates,

and less directly, long-term interest

rates. However, increases to the

Federal funds rate have yet to drive

similar increases in longer-term yields.

In fact, over the 12 months that the

Chart 2

FOMC has moved the target Federal

funds rate steadily upward, the nominal

yield on the 10-year treasury has rarely

crested above 4.5 percent and actually

has declined from its July 2, 2004,

level. This “conundrum,” evidenced by

nonparallel movement in short- and

long-term rates, has resulted in a flat-

tening of the yield curve.

1

Looking forward, many market partici-

pants anticipate further measured

increases in the Federal funds rate and

similar, although not equal, increases

in longer-term rates. Over the next

year, Blue Chip Financial Forecasts

2

is predicting an additional 130 basis

point increase in short-term rates and

a 104 basis point increase in longer-

term rates—a forecast that portends

continued flattening of the yield curve

(see Chart 2).

Forecasted change of 10-Year

Treasury Bond over the next 12

months = 104 bps

Continued Flattening of the Yield Curve Is Forecasted

Years

Source: Blue Chip Financial Forecasts (BCFF)

Forecasted change of 3-Month

Treasury Bill over the next 12

months = 130 basis points

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

BCFF for week ended April 22, 2005 BCFF for Fourth Quarter of 2005 BCFF for Second Quarter of 2006

1

The Federal funds rate is the interest rate at which depository institutions lend balances overnight from the

Federal Reserve to other depository institutions. The intended Federal funds rate is established by the FOMC of

the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan said during his February 16, 2005,

monetary policy testimony to the Senate Banking Committee, “For the moment, the broadly unanticipated behavior

of world bond markets remains a conundrum.” (Source: Bloomberg News)

2

Blue Chip Financial Forecasts is based on a survey providing the latest in prevailing opinions about the future

direction and level of U.S. interest rates. Survey participants such as Deutsche Banc Alex Brown, Banc of

America Securities, Fannie Mae, Goldman Sachs & Co., and JPMorganChase provide forecasts for all significant

rate indices for the next six quarters.

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

6

Assessing Banks’ Interest Rate

Risk Exposure

A rising rate environment in conjunc-

tion with a continued flattening of the

yield curve presents the potential for

heightened interest rate risk. A flattening

yield curve can pressure banks’ margins

generally, and rising rates can be particu-

larly challenging to institutions with a

“liability-sensitive” balance sheet—an

asset/liability profile characterized by

liabilities that reprice faster than assets.

The extent of this mismatch between the

maturity or repricing of assets and liabili-

ties is a key element in assessing an insti-

tution’s exposure to interest rate risk.

The shape of the yield curve is an

important factor in assessing the overall

rate environment. A steep yield curve

provides the greatest spread between

short- and long-term rates and is gener-

ally associated with favorable economic

conditions. Long-term investors, antici-

pating an improving economy and higher

rates, will demand greater yields to

compensate for the risk of being locked

Chart 3

into longer-term assets. In such a favor-

able environment, opportunities exist to

generate spread-related earnings driven

by asset and liability term structures.

A flattening yield curve can deprive

banks of these opportunities and raises

concern about a possible inversion in

the yield curve. An inverted yield curve,

where long-term rates are lower than

short-term rates, can present a most

challenging environment for financial

institutions. Also, an inverted yield curve

is associated with the potential for

economic recession and declining rates.

Given recent rising rates and flattening

of the yield curve, bank supervisors have

been monitoring trends in bank net

interest margins (NIMs) and balance

sheet composition.

While various factors (competition,

earning asset levels, etc.) affect NIMs,

a flattening yield curve is associated

with declining NIMs. Chart 3 shows that

during the 1990s, generally declining

industry NIMs followed the overall flat-

tening of the yield curve. As the spread

between long- and short-term rates (the

bars) generally decreased from 1991 to

Net Interest Margins (NIMs) Are Trending Down

3.3

3.5

3.7

3.9

4.1

4.3

4.5

4.7

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

-50

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

NIM

Trailing 4-quarter NIM

Treasury Yield Spread—

the difference between

the 10-year and 3-month

Treasury rates—on a

3-month moving average

Yield

Spread

Note: Median NIMs for banks excluding specialty banks.

Source: FDIC and Federal Reserve

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

7

Interest Rate Risk

continued from pg. 7

1999—resulting in a flattening of the

Treasury yield curve—bank NIMs also

declined (the line on Chart 3 plots trail-

ing four-quarter NIM). Beginning in

2000, after a brief period of inversion,

the yield curve steepened dramatically,

and over the next five quarters, bank

NIMs increased. NIMs have since contin-

ued their general decline, and recent

quarters have seen the yield curve

continue to flatten, raising the potential

for continued pressure on bank NIMs.

Even though median bank NIMs have

been declining since 1994, this trend

has been accompanied by strong and, in

recent years, record levels of profitability.

Noninterest income sources (combined

with overall strong industry perfor-

mance) have helped mitigate the effects

of declining NIMs. Institutions with over

$1 billion in assets report significant

reliance on noninterest income; it

accounts for more than 43 percent of

their net operating revenue. While this

diversification of income sources is less

prevalent in smaller community banks

(institutions that hold less than $1 billion

in assets derive only 25 percent of net

operating revenue from noninterest

income sources), NIMs reported by these

smaller institutions generally are higher

and recently have improved compared to

those of the larger institutions.

In short, while individual banks may

be experiencing margin pressures, the

downward trend in bank NIMs has yet

to result in an industry-wide decline in

levels of net income. It is too early to

gauge the effects of a continuing or

prolonged period of flattening in the

shape of the yield curve.

3

Bank Balance Sheet

Composition—The Asset Side

Despite strong industry profitability,

bank supervisors are monitoring changes

in the nature, trend, and type of expo-

sures on bank balance sheets. Recent

aggregate balance sheet information

shows the industry increasing its expo-

sure to longer-term assets, holding

greater proportions of mortgage-related

assets, and relying more on rate-sensitive,

noncore funding sources—all factors

that can contribute to higher levels of

interest rate risk.

4

In general, the earnings and capital

of a liability-sensitive institution will be

affected adversely by a rising rate envi-

ronment. A liability-sensitive bank has a

long-term asset maturity and repricing

structure relative to a shorter-term liabil-

ity structure. In an increasing interest

rate environment, the NIM of a liability-

sensitive institution will worsen (other

factors being equal) as the cost of the

bank’s funds increases more rapidly

than the yield on its assets. The higher

its proportion of long-term assets, the

more liability-sensitive a bank may be.

The industry’s exposure to long-term

assets increased during the 1990s (see

Chart 4). Exposure to long-term assets in

relation to total assets has risen steadily,

from 13 percent in 1995 to nearly 24

percent in 2004, indicating the potential

for heightened liability sensitivity.

5

Signifi-

cant exposure to longer-term assets could

generate further inquiry from examiners

about the precise cash flow characteris-

tics of a particular bank’s assets and a

review of the bank’s assessment of the

3

Refer to the Fourth Quarter 2004 FDIC Quarterly Banking Profile for complete 2004 industry performance results.

4

Except where noted otherwise, data are derived from the December 31, 2004, Consolidated Reports of Condition and

Income (Call Reports). Call Reports are submitted quarterly by all insured national and state nonmember commer-

cial banks and state-chartered savings banks and are a widely used source of timely and accurate financial data.

5

Long-term assets include fixed- and floating-rate loans with a remaining maturity or next repricing frequency

of over five years; U.S. Treasury and agency, mortgage pass-through, municipal, and all other nonmortgage debt

securities with a remaining maturity or repricing frequency of over five years; and other mortgage-backed secu-

rities (MBS) like collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs), real estate mortgage investment conduits (REMICs),

and stripped MBS with an expected average life of over three years.

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

8

Chart 4

Exposure to Longer-Term Assets Is Increasing

Year

Longer-term asset holdings hit

a high of 23.8% in March 2004

and declined slightly to 22.4%

by year-end 2004

Ratio to

Total Assets

23%

13%

15%

17%

19%

21%

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Source: FDIC

Note: All FDIC-Insured Commercial Banks.

nature and extent of its asset-liability

mismatch and resulting rate sensitivity.

In addition to increasing its exposure

to long-term assets, the industry has

increased its exposure to mortgage-

related assets. Current data show that

bank holdings of mortgage loans and

mortgage-backed securities comprise 28

percent of all bank assets (see Chart 5),

6

compared to 18 percent in 1990.

Mortgage-related assets present unique

risks because of the prepayment option

that is granted the borrower and embed-

ded within the mortgage loan. Due to

lower prepayments in a rising rate envi-

ronment, the duration of lower-coupon,

fixed-rate mortgages will extend and

banks will be locked into lower-yielding

assets for longer periods. Like mortgage

loans, longer-term, fixed-rate mortgage-

backed securities are also exposed to

extension risk.

It is difficult to assess fully the current

magnitude of liability sensitivity or exten-

sion risk confronting the banking indus-

try. Even though exposure to long-term

and mortgage-related assets has been

moving steadily upward in recent years,

there are signs that bank risk managers

are responding to a changing rate envi-

ronment and altering their asset mix.

Since June 2003, banks have reduced

their exposure to fixed-rate mortgage

assets and are recently offering more

adjustable-rate mortgage loan products

(ARMs). As shown in Chart 6, industry

exposure to fixed-rate mortgages, while

generally increasing since 1995, began

to turn sharply downward in the third

quarter of 2003.

And, according to Federal Housing

Finance Board data, the percentage of

adjustable-rate, conventional single-

family mortgages originated by major

6

Mortgage-related assets includes loans secured by one- to four-family residential properties, including revolving

lines of credit, and closed-end loans secured by first and junior liens; mortgage pass-through securities and MBS,

including CMOs, REMICs, and stripped MBS. Extension risk can be explained as follows: Changes in interest rates

can pressure the value of mortgages and MBS because of the embedded prepayment option held by the mortgage

debtor. These options can affect the holder of such assets adversely in a falling or rising rate environment. As

rates fall, mortgages likely will experience higher prepayments, requiring the bank to reinvest the proceeds in

lower-yielding assets. Conversely, as rates rise, prepayments will slow and result in a longer, extended period

for principal return.

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

9

Interest Rate Risk

continued from pg. 9

Chart 5

Bank Balance Sheets Are Heavily Exposed to Mortgage-Related Assets

Interest and noninterest

bearing balances

5%

Other loans

15%

Consumer loans

10%

Other assets

18%

Source: FDIC

Note: Commercial Bank Assets as of December 31, 2004.

Chart 6

1–4 family loans

and MBS

28%

CRE loans

5%

Other securities

8%

C&I loans

11%

Fixed-Rate Mortgage-Related Loans Reverse Trend

Ratio to

Total Assets

Fixed-rate mortgage holdings

generally increased until September

2003, and subsequently dropped

sharply to 8.65% of total assets.

11.0%

10.5%

10.0%

9.5%

9.0%

8.5%

8.0%

7.5%

7.0%

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Year

Source: FDIC

Note: All FDIC-Insured Commercial Banks. Fixed-Rate loans secured by 1–4 family residential properties.

lenders increased from 15 percent in

2003 to a recent peak of 40 percent in

June 2004. Lower levels of fixed-rate

mortgages would reduce an institution’s

exposure to extension risk. In addition,

higher levels of ARMs could increase

an institution’s asset sensitivity. Such

changes in balance sheet structure

could mitigate potential exposure to

rising interest rates.

7

7

All ARMs are not the same, and the degree of asset sensitivity will depend on each product’s unique structure.

ARMs with an initial fixed-rate period of one to five years (“hybrid” loans) have grown in popularity. Freddie

Mac’s 2004 ARM Survey found that 40 percent of all adjustable-rate mortgages were hybrid products, primarily

3/1 and 5/1 structures. The interest rate on such hybrid loans are fixed for three or five years, respectively,

adjusting annually thereafter based on some interest rate index. Accordingly, such hybrid products will not

reduce liability sensitivity during the fixed-rate period of the loan.

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

10

Bank Balance Sheet

Composition—

The Liability Side

The potential for interest rate risk

driven by maturity or repricing mismatch

cannot be assessed by looking only at

the asset side of the balance sheet.

Information on the nature and dura-

tion of banks’ liabilities is also needed.

Banks that rely heavily on short-term

and more rate-sensitive funding sources

could experience a material increase

in funding costs as interest rates rise.

Some banks may not be able to offset

such higher funding costs through

increased asset yields. Increased expo-

sure to short-term, rate-sensitive whole-

sale funding sources can render a bank

more liability sensitive, increasing its

exposure to rising rates.

Over the past several years, banks

have increased their reliance on whole-

sale, noncore funding sources such as

overnight funds, certificates of deposit

(greater than $100,000), brokered

deposits, and Federal Home Loan Bank

(FHLB) advances. Noncore funding

Chart 7

sources have climbed steadily from about

25 percent of total assets in 1992 to over

35 percent today. This trend is mirrored

by core deposits falling from 62 percent

of total assets in 1992 to 48 percent in

2004 (see Chart 7). Combined with an

increase in holdings of long-term assets,

a shorter-term and more volatile liability

structure could expose an institution to

significant interest rate risk in a rising

rate environment.

To assess fully the impact of the

increase in noncore funding sources

and the decrease in core deposits, more

information about the tenor of noncore

liabilities is needed. FHLB advances are

a significant component of noncore fund-

ing for many institutions and illustrate

the importance of looking deeper into

the repricing structure of a bank’s fund-

ing sources. Call Report data provide

some information on the maturity struc-

ture of FHLB advances, but the picture is

clouded. Recent reports show that while

the use of shorter-term FHLB advances

(under one year) has been on the rise,

67 percent of all FHLB advances have a

maturity greater than one year (see

Chart 8).

Year

Source: FDIC

Banks Increase Reliance on Noncore Funding Sources

Ratio to

Total Assets

Note: All FDIC-Insured Commercial Banks. Noncore liablities include time deposits over $100 million, other borrowed money,

Federal funds purchased and securities sold, insured brokered deposits less than $100,000, and total foreign office deposits.

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

25%

65%

30%

35%

40%

45%

50%

55%

60%

Noncore Liabilities

Core Deposits

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

11

Interest Rate Risk

continued from pg. 11

Chart 8

Use of Shorter-Term FHLB Advances Is Increasing

2001 2002 2003 2004

Year

Source: FDIC

38% of Total

29% of Total

33% of Total

FHLB Advances

(in billions)

FHLB advances with a remaining maturity of one year or less

FHLB advances with a remaining maturity of more than one year through three years

FHLB advances with a remaining maturity of more than three years

$0

$20

$40

$60

$80

$100

$120

$140

$160

The Call Report, however, does not

capture the nature and extent of options

embedded within the FHLB advance

structures. Call Report instructions

provide that FHLB advances with a three-

year (or longer) contractual maturity are

to be recorded in the long-term bucket,

even if the advance is callable or convert-

ible by the FHLB at any time. A callable

or convertible advance allows the FHLB

to convert the advance from fixed- to

floating-rate or terminate the advance and

renew the extension at current market

rates. Therefore, advances such as those

reported as having a three-year maturity

may actually reprice in the near term,

depending on the rate environment.

8

Many advances contain embedded

options. The FHLB Combined Financial

Report (as of June 30, 2004) reflects

that of then-outstanding advances,

approximately 55 percent were callable

and 22 percent were convertible. Trans-

lated to bank balance sheets, these data

indicate the presence of a greater level

of option risk on banks’ balance sheets

than currently included in Call Report

information. In a rising rate environ-

ment, the probability increases that

the FHLB will exercise its option to call

or convert lower-yielding advances,

thereby exposing the borrowing

institution to higher funding costs.

In conclusion, aggregate industry

trends—specifically higher levels of

exposure to long-term assets, mortgage-

related assets, and noncore funding

sources that exhibit optionality—raise

concerns about the potential for height-

ened levels of interest rate risk in today’s

environment. These concerns must be

tempered by awareness that off-site data

provide only a rough, opaque, and end-

of-period view of banks’ balance sheet

cash flow characteristics and composi-

tion. Each bank is unique in terms of

asset and liability mix, risk appetite,

hedging activities, and related risk

profile. Moreover, bank risk exposures

are not static. Interest rate risk man-

agement strategies can change an

institution’s risk profile quickly—even

overnight—through the use of financial

derivatives (e.g., interest rate swaps).

8

See Instructions for Preparation of Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (FFIEC 031 and 041) at

RC-M–Memorandum Item 5, which provides, “Callable Federal Home Loan bank advances should be reported

without regard to their next call date unless the advance has actually been called.”

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

12

Thus, it is difficult to draw conclusions

about the level of interest rate risk

strictly from off-site information. Off-site

and industry-wide analyses must be

joined with on-site examination results

to derive a more comprehensive super-

visory assessment of interest rate risk

exposure, its measurement, and its

management.

Supervisory Assessment of

Interest Rate Risk

Bank examiners assess the level of

interest rate risk exposure in light of

a bank’s asset size, complexity, levels

of capital and earnings, and most

important, the effectiveness of its risk

management process. At the core of

the interest rate risk examination

process is a supervisory assessment

of how well bank management identi-

fies, monitors, manages, and controls

interest rate risk.

9

This assessment

is summarized in an assigned risk

rating for the component known as

sensitivity to market risk, which is

part of the CAMELS rating system.

10

An unsatisfactory rating for sensitivity

to market risk (the “S” component of

CAMELS) represents a finding of mate-

rial weaknesses in the bank’s risk

management process or high levels of

exposure to interest rate risk relative to

earnings and capital. Chart 9 indicates

that the number of FDIC-insured insti-

tutions with an unsatisfactory “S” com-

ponent rating is minimal out of the

population of nearly 9,000 insured insti-

tutions. Fewer than 5 percent of insured

institutions are rated 3 or worse for this

component, and most of those are in the

less severe 3 rating category. Moreover,

since 2000, the number of institutions

with an adverse “S” component rating

has declined steadily.

To capture emerging trends, FDIC

supervisors are conducting periodic

reviews of bank examination reports in

an effort to discern the nature and cause

of adverse “S” component ratings. A

review of recent examination reports that

presented supervisory concerns about

interest rate risk reveals several common-

alities in the banks’ operating activities:

• Concentrations in mortgage-related

assets,

• Ineffective or improperly managed

“leverage” programs,

11

and

• Acquisition of complex securities

without adequate prepurchase and

ongoing risk analyses.

9

“Effective board and senior management oversight of a bank’s interest rate risk activities is the cornerstone of

a sound risk management process.” Joint Agency Policy Statement on Interest Rate Risk, 12 FR 33166 at 33170

(1996); distributed under Financial Institution Letter 52-96 (hereafter Interest Rate Risk Policy Statement).

10

Sensitivity to market risk is rated under the Uniform Financial Institutions Rating System (UFIRS), which is used

by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council member regulatory agencies. Under the UFIRS, each

financial institution is assigned a composite rating based on an evaluation and rating of six essential components

of an institution’s financial condition and operations: the adequacy of capital (C), the quality of assets (A), the

capability of management (M), the quality and level of earnings (E), the adequacy of liquidity (L), and the sensitivity

to market risk (S). The resulting acronym is referred to as the CAMELS rating. Composite and component ratings

are assigned based on a 1 to 5 numerical scale. 1 indicates the highest rating, strongest performance and risk

management practices, and least degree of supervisory concern, while 5 indicates the lowest rating, weakest

performance, inadequate risk management practices, and, therefore, the highest degree of supervisory concern.

In general, fundamentally strong or sound conditions and practices are reflected in 1 and 2 ratings, whereas

supervisory concerns and unsatisfactory performance are increasingly reflected in 3, 4, and 5 ratings.

11

A “leverage” strategy is a coordinated borrowing and investment program with the goal of achieving a positive

net interest spread. Leverage programs are intended to increase profitability by leveraging the bank’s capital

through the purchase of earning assets using borrowed funds. While “leverage” in general defines banking, a

typical leverage strategy focuses on a bank’s acquisition of wholesale funding, such as Federal Home Loan Bank

advances, and the targeted investment of such proceeds into bonds with a different maturity or credit rating, or

both, such that a higher yield is earned from the bonds than the interest rate on the borrowings. Profitability may

be achieved if a positive net interest spread is maintained, despite changes in interest rates. When improperly

managed, these strategies cause increased interest rate risk and supervisory concern.

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

13

Interest Rate Risk

continued from pg. 13

Chart 9

Source: FDIC

Unsatisfactory “S” Component Ratings Are Declining

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

373

418

555

510

457

366

356

28

30

53

34

27

29

22

1

1

4

0

3

1

5

5 Rated

4 Rated3 Rated

In addition, concerns have emerged

about the adequacy and effectiveness

of bank management’s use of interest

rate risk models. Weaknesses center

on (1) the accuracy of model inputs

as well as the accuracy and testing of

assumptions, (2) whether the models

are capturing the cash flow characteris-

tics of complex instruments, specifically

instruments with embedded options,

and (3) whether management is using

adequate stress tests to determine

sensitivity to interest rate changes.

Key supervisory concerns identified

from a review of examination com-

ments specific to interest rate risk

models include:

• Data input should be accurate,

complete, and relevant. Many

loans, securities, or funding items

may present complex or unique

cash flow structures that require

special, tailored data entry. Aggre-

gating structural information at too

high a level may result in the loss of

necessary detail, and the reliability

of the cash flows projections may

become questionable.

• Assumptions must be appropriate

and tested. Model results are

extremely sensitive to the assump-

tions used; these assumptions should

be reasonable and reviewed periodi-

cally. For example, prepayment

speeds can change significantly in

any given rate environment. And

a bank’s historical prepayments

experience may differ materially

from vendor-supplied prepayment

speeds. The model’s sensitivity to

changes in key material assumptions

should be evaluated periodically.

• Option risk embedded in assets

and funding sources should be

captured effectively. Many banks

have options embedded in their

balance sheet through exposure

to mortgage-related assets, callable

or convertible advances, or other

structured products. Interest rate

risk measurement systems should

be capable of identifying and

measuring the effect of embedded

options.

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

14

• Significant leverage programs

should be understood fully. Man-

agement should understand fully

the nature of the leverage programs

and the risks of the instruments

used, and effectively assess the

impact of adverse rate movements

or yield curve changes. Given that

leverage programs often are

designed to take advantage of

spreads between short- and long-

term rates, measurement systems

should capture the effects of

nonparallel shifts of the yield curve.

• Sensitivity stress tests should include

a reasonable range of unexpected

rate shocks; for example, stress

tests should not simply approxi-

mate market expectations of a

modest ratcheting up of the yield

curve over the next 12 months.

Bank management should provide

for stress tests that include potential

interest rate changes and meaningful

stress situations using a sufficiently

wide range in market interest rates,

immediate and gradual shifts in

market rates, as well as changes in

the shape of the yield curve. The

Interest Rate Risk Policy Statement

suggests at least a 200 basis point

shock over a one-year horizon.

• The variance between the model’s

forecasted risk levels and actual

risk exposures should be analyzed

routinely (sometimes called “back-

testing”). This exercise will highlight

areas of material variance and

improve identification of errors in

assumptions, inputs, or calculations.

Lessons from History Help

Place Concerns About Rising

Rates in Context

Current concerns about the risks of

a rising rate environment should be

viewed in historical context. An internal

FDIC review of bank and thrift failures

discloses that interest rate risk is not a

common cause of insured depository

institution insolvencies.

The FDIC review studied the causes

of the bank insolvencies that occurred

during three periods of rising rates: the

period from 1978 to 1982 and the rate

spikes in 1994 and 2000. The analysis

revealed that no institution failures in

the 1990s were caused by the move-

ment of interest rates. However, certain

insolvencies in the early 1980s, prima-

rily of savings and loan institutions,

were affected by changes in the inter-

est rate environment. The review deter-

mined that these insolvencies followed

a period of rapid and prolonged

increases in short- and long-term rates,

during which the yield curve was

inverted (for the most part, the yield

curve was inverted from September

1978 through April 1982). These insti-

tutions were heavily concentrated in

longer-term, fixed-rate mortgage loans,

and were also challenged by a new and

unregulated market for deposits. Addi-

tional factors that contributed to these

early insolvencies were economic reces-

sion, capital weakness, and regulatory

forbearance. A historical depiction of

institution failures, in relation to the

10-year Treasury bond yield and

general periods of yield curve inver-

sion, is shown in Chart 10. From a

historical perspective, only in the

unique circumstances of the early

1980s can rising rates be associated

with bank or thrift insolvency.

Today’s environment is markedly

different. Despite rising rates and a flat-

tening yield curve, the curve remains

upward sloping. The economy generally

has been improving, and the regulatory

environment has changed considerably.

Stricter regulatory capital standards

were mandated in 1988, and limits on

permissible investments were adopted

in 1989. Prudential standards were

implemented following the enactment

of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corpo-

ration Improvement Act of 1991, and

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

15

Interest Rate Risk

continued from pg. 15

Chart 10

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

1954 1958 1962 1966 1970 1974 1978 1982 1986 1990 1994 1998 2002

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

Source: Haver Analytics, Federal Reserve, and FDIC

Note: Failure data prior to 1980 include only commercial bank failures.

Post-FDICIA

Periods of Inverted Yield Curve

A Historical Review Places Today’s Concerns in Context

10-Year

Treasury Rate

Bank/Thrift

Failures

10-Year Treasury Bond Yield

# of Commercial Bank/Thrift Failures

interest rate risk and investment activi-

ties policy statements were issued in

1996 and 1998. In addition, the indus-

try now relies on more advanced interest

rate risk measurement and manage-

ment methodologies. Taken together,

these developments mitigate the level

of supervisory concern about the aggre-

gate level of interest rate risk in the

industry today.

Conclusion

Interest rate risk is garnering atten-

tion given the changing rate environ-

ment and trends in aggregate bank

balance sheet and income statement

information. Rising rates and a flatten-

ing yield curve could pressure NIMs,

particularly for institutions that exhibit

liability sensitivity, given their rela-

tively greater exposure to long-term

assets. In addition, banks are exhibit-

ing increased exposure to more

volatile, rate-sensitive funding sources

with degrees of optionality not fully

captured by Call Report data. How-

ever, these aggregate measures of

bank balance sheet and income state-

ment composition serve only as indi-

cators of the possible presence of

interest rate risk. Off-site analysis and

on-site examinations identify excessive

or poorly managed interest rate risk

relative to a particular institution’s

risk profile, earnings, and capital

levels. Examination findings, while

revealing weaknesses in some circum-

stances, overall indicate that bank risk

managers are acting effectively to

moderate their institutions’ exposure

to interest rate risk in this challenging

environment.

Keith Ligon

Chief, Capital Markets Branch

The author acknowledges the assis-

tance provided by Examiners Thomas

Wiley, Lawrence Reynolds, and John

Falcone in the Division of Supervision

and Consumer Protection; and Finan-

cial Analyst Douglas Akers with the

Division of Insurance and Research,

in the preparation of this article.

Supervisory Insights Summer 2005

16