1

ADDRESSING FORCED LABOUR AND

HUMAN TRAFFICKING IN UN SUPPLY

CHAINS

Guidance for UN Staff

19 September 2022

CEB/2022/HLCM/19

2

CONTENTS

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 4

1. About this Guidance .......................................................................................................................................... 8

1.1 Structure and logic of the Guidance ............................................................................................................

9

1.2 Who should use this Guidance? .................................................................................................................. 9

2. Background and concepts ................................................................................................................................ 12

2.1 Defining forced labour and human trafficking .......................................................................................... 12

2.2 UN commitments to combatting forced labour and human trafficking in its supply chains ..................... 14

2.3 Human rights due diligence and procurement .......................................................................................... 16

2.4 UN procurement objectives and values .................................................................................................... 18

2.4.1 Sustainable public

procurement

......................................................................................................... 18

2.4.2 Aligning UN procurement with UN commitments on forced labour and human trafficking .............. 20

3. Addressing Forced Labour and Human Trafficking in the Procurement Cycle .................................................. 24

3.1 Risk identification, assessment and management .................................................................................... 25

3.1.1 Identifying forced labour and human trafficking risks ....................................................................... 26

3.1.2 Assessing and mitigating risks ............................................................................................................ 29

3.2 Sourcing .................................................................................................................................................... 31

3.3 Supplier registration and the UN Global Marketplace (UNGM) ................................................................ 35

3.4 Requirements definition ........................................................................................................................... 36

3.5 Supplier

qualification

.................................................................................................................................. 40

3.6 Evaluation and award criteria ................................................................................................................... 42

3.7 Contractual provisions .............................................................................................................................. 46

3.8 Contract management .............................................................................................................................. 51

3.8.1 Supplier dialogue during contract implementation ........................................................................... 53

3.8.2 Supplier monitoring ........................................................................................................................... 54

3.8.3 Corrective action and

disengagement

................................................................................................. 59

3.9 Sanctions ................................................................................................................................................... 63

3.10 Actions to take when a forced labour or human trafficking issue arises ................................................. 65

4. Cross-cutting

considerations

............................................................................................................................. 67

4.1 Remedy for victims and survivors of human rights

abuses

........................................................................ 67

3

Note:

This Guidance and the resources contain examples of current practice and are not to be construed as an

endorsement of any nature nor are they intended to modify the existing commitments, responsibilities

and obligations of UN Organizations. This Guidance is designed to support UN Organizations and is not a

standard for UN Organizations to be measured on.

4.2 Supplier engagement and support ............................................................................................................ 71

4.3 Emergency procurement ........................................................................................................................... 77

4.4 Support for UN personnel ......................................................................................................................... 81

4.5 The role of donors and national stakeholders ........................................................................................... 84

4.6 Reporting................................................................................................................................................... 86

Annex 1 - Glossary of Terms ................................................................................................................................ 87

Annex 2 - Reporting ............................................................................................................................................. 89

Annex 3 – Additional resources ........................................................................................................................... 91

Annex 4 – Case studies ........................................................................................................................................ 95

Case Study 1 – A full procurement cycle approach in practice at the OSCE ..................................................... 95

Case Study 2 – Sustainable procurement at UNOPS ........................................................................................ 99

Case Study 3 – Social audits at the UNHCR .................................................................................................... 101

Annex 5 – Suggested

Clauses

............................................................................................................................. 103

End Notes .......................................................................................................................................................... 107

Acknowledgment

This Guidance document was developed by the UN High Level Committee on Management Procurement

Network (HLCM-PN) Task Force for the Development of a Joint Approach to Combatting Human Trafficking

and Forced Labour in Supply Chains, with the support of the Danish Institute of Human Rights (DIHR) and

University of Greenwich.

For the purposes of this Guidance, the term UN Organization(s) refers to all bodies in the UN system,

covering i) UN Funds and Programmes, ii) UN Specialised Agencies, iii) Other Entities and Bodies, and iv)

Related International and Regional Organizations.

Document Number: to be added

Copyright: to be added

4

Executive

Summary

The elimination of forced labour and human trafficking is a central challenge for the international

community. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) 40.3 million people are in modern

slavery, which includes those in forced and bonded labour, child labour, victims of human trafficking and

those subjected to domestic servitude and forced marriages. Forced labour and human trafficking are not

confined to some countries or sectors, they are a universal issue, and occur both behind closed doors and in

plain sight.

With United Nations (UN) procurement of goods and services (including works) totalling USD $22.3 billion in

2020 from suppliers in over 200 countries and territories around the world, the UN supply chains are at risk

of instances of forced labour and human trafficking. This risk is present throughout the procurement cycle

and should be addressed from the level of policy through to implementation.

The UN Security Council Resolution S/RES/2388 calls upon UN system organizations to enhance transparency

in their procurement and supply chains and step up their efforts to strengthen protections against trafficking

in persons in all UN procurement. The UN General Assembly Resolution 76/7 urges the Secretary-General to

ensure that UN procurement does not contain goods and services produced by trafficked persons, and

ECOSOC Resolution 2021/25 requests that UN agencies ensure that UN procurement is free from trafficking

in persons.

In order to have an effective impact in mitigating this risk of forced labour and human trafficking in

UN supply chains, UN procurement policy should reflect this responsibility throughout UN system

organizations. This Guidance has been developed on the basis of the UN recognition of the need to work

collaboratively with its suppliers and across all UN Organizations to effectively address the risks of forced

labour and human trafficking in its supply chains. This Guidance reflects the UN’s commitment to establishing

a common approach applicable to all UN Organizations and any entity contracting with an Organization

within the UN for the provision of goods or services to tackle the risk of forced labour and human trafficking

in UN supply chains in a collaborative manner. The Guidance is relevant for procurement staff, legal staff,

compliance and oversight staff, requisitioners/ contract managers, policy leads, and human trafficking and

forced labour experts.

The following sections highlight main points to guide staff through their efforts to address forced labour and

human trafficking in UN procurement.

Addressing risks of forced labour and human trafficking is integral to the role and mandate of the UN

The UN should serve as a role model with the duty to respect international human rights standards and

contribute to the protection of the rights of workers. In many contexts, UN Organizations have considerable

influence in certain markets due to the scale of their procurement activities.

Through their purchasing function, UN Organizations can not only promote UN values to the market, but also

support their implementation, thereby shaping business practices worldwide. By adopting forced labour and

5

human trafficking considerations when undertaking procurement activities, UN Organizations can contribute

to developing best practices. They too have significant leverage, i.e. the ability to influence the behaviour of

their suppliers and those in their supply chain. In other words, UN Organizations can and should require their

suppliers to contribute to UN efforts to combat forced labour and human trafficking. Find more details in

section 2 of the Guidance on Background and Concepts.

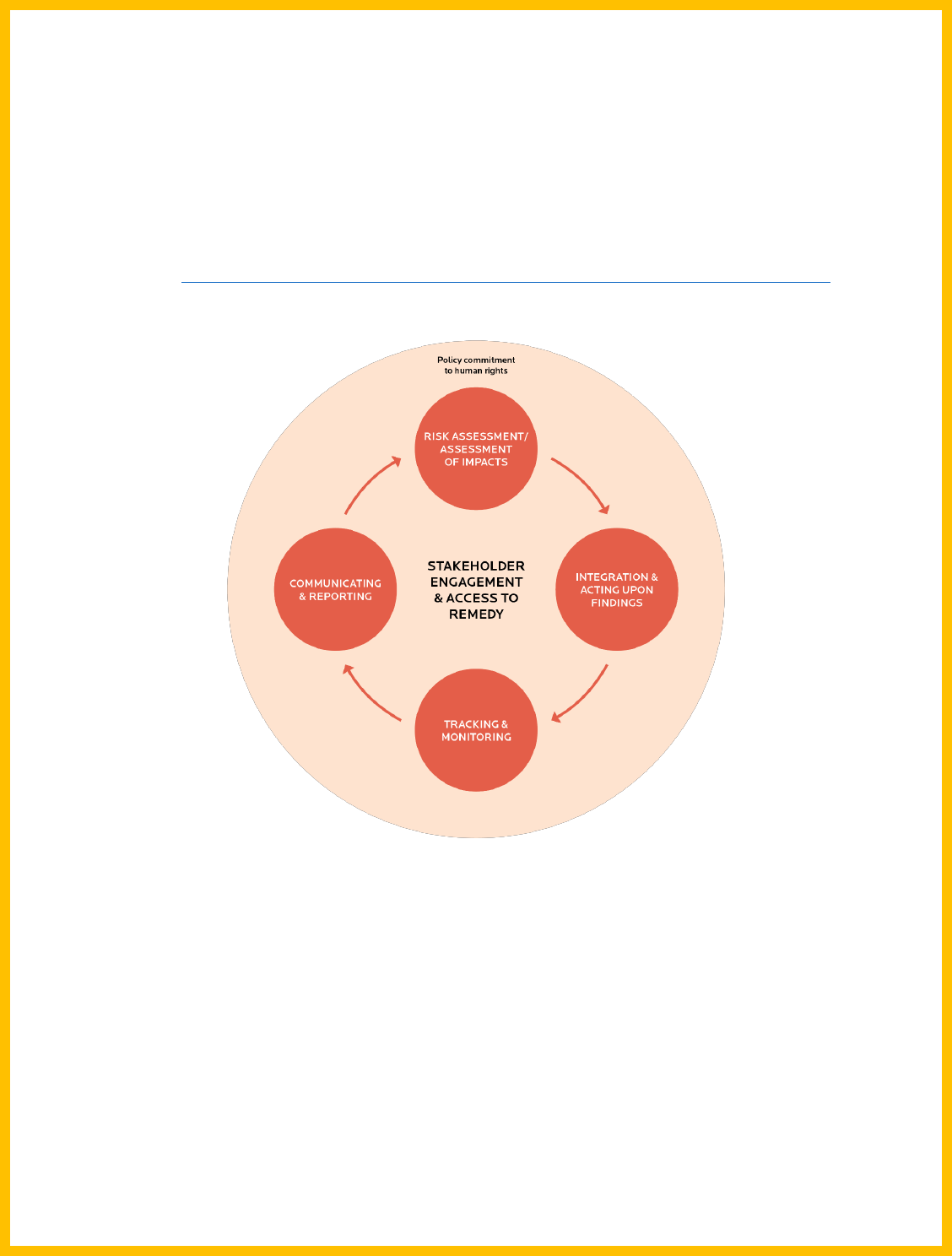

A process of human rights due diligence is central to addressing forced labour and human trafficking in UN

procurement

Human rights due diligence is a risk management process detailed in the UN Guiding Principles on Business

and Human Rights (UNGPs). By undertaking human rights due diligence, an organization can identify,

prevent, mitigate and account for human rights impacts that it may cause or contribute to through its own

activities, including those which may be directly linked to its operations, products or services via its

commercial relationships. Introducing measures to address the risk of forced labour and human trafficking

into risk management and procurement activities is one of the essential ways UN Organizations may conduct

human rights due diligence in their supply chains.

The risk of forced labour and human trafficking in UN procurement should be addressed across the

different stages of the UN procurement cycle from policy, through to planning, tendering, and contract

management

Having policies to address the risk of forced labour and human trafficking in UN supply chains is the first step

in responding to these challenges. These policies should include the identification and the assessment of

these risks specifically in relation to the UN Organization’s supply chain. Once this has been done, measures

to require suppliers’ respect for human rights can be defined, prioritised, and included in different stages of

the procurement cycle to prevent these risks from becoming realities.

Although certain parts of the procurement cycle can appear as the most appropriate phase for planning or

intervention, it is fundamental to consider the whole procurement cycle so that the different stakeholders

can be identified and engaged during the procurement process.

It is necessary to approach this strategically, so that forced labour and human trafficking risks are managed at

an early stage of sourcing and the most appropriate supplier can be selected through a competitive and

rigorous selection process.

It is important to implement approaches and requirements that respond to the forced labour and human

trafficking risks identified, and are appropriately weighted and communicated to the market. Furthermore,

consideration is to be given to how these requirements will be monitored and managed throughout the life

of the contract.

Ongoing engagement with suppliers through review meetings, progress reports, improvement

programmes, key performance indicators (KPIs), and in some cases site inspections and audits, allow for

forced labour and human trafficking risks to be identified at an early stage. Through monitoring, a UN

6

Organization can evaluate how a supplier is strengthening its own due diligence processes to address such

risks.

For more information on these points as well as examples of current practices in UN Organizations, see

section 3 on Addressing Forced Labour and Human Trafficking in the Procurement Cycle as well as section 4

on Crosscutting Considerations.

Cooperation and collaboration among UN Organizations is key to addressing the issue

Cooperation and collaboration are necessary to increase leverage, share costs, reduce administrative

burdens, realise economy of scale, and share good practice. UN Organization collaboration also means that

suppliers receive the same message and fair treatment from different UN Organizations promoting common

standards on forced labour and human trafficking for supply chains. Examples and guidance on this can be

found throughout the Guidance.

Victims and survivors should be at the centre of remediation efforts

Forced labour and human trafficking are serious human rights abuses which have profound and long-lasting

effects on victims and survivors. Those who suffered harm are to be at the centre of measures to address

forced labour and human trafficking, and efforts should be made to facilitate their access to effective remedy

where abuses occur, in line with international standards and the applicable referral procedures in the

concerned country.

Where suppliers to UN Organizations are found to have engaged in practices that may lead to forced labour

and/or human trafficking, continued engagement is preferable, because it allows for the instances of abuse

to be addressed and ideally would result in an improved situation for victims. However, where

a serious violation by the supplier is identified and/or there is no genuine interest from the supplier to

address the situation, then disengagement, contract termination and engagement with authorities on

remedy may be necessary. For more information, see the Background and Concepts section 2 of the

Guidance, as well as section 3 on Addressing Forced Labour and Human Trafficking in the Procurement Cycle

and section 4 on Crosscutting Considerations.

Long lasting change relies on capacity, knowledge, engagement and collaboration

Engagement, collaboration and capacity building and development are key to addressing the risk of forced

labor and human trafficking in UN supply chains. This is relevant for all actors involved:

- UN Organizations should provide support to suppliers on how to address the issue in their own

operations and with their suppliers and contractors;

- UN Organizations should provide personnel with the required knowledge and capacity to engage

with suppliers and other stakeholders on forced labour and human trafficking;

- UN Organizations should share good practice and collaborate with one another, communicating this

as a priority for the One UN to the market; and

7

- UN Organizations, as and where appropriate, should share costs and potentially reduce

administrative burdens and realise economies of scale.

Communication and transparency are central to learning and continuous improvement

Exercising human rights due diligence requires not only assessing and addressing human rights risks, but also

communicating the actions taken. Reporting and publicly disclosing a UN Organization’s actions and progress

in contributing to the fight against forced labour and human trafficking is a fundamental element of human

rights due diligence in supply chains. UN Organizations are encouraged to report annually on how they are

implementing human rights due diligence in their own procurement activities. Guidance on reporting can be

found in section 4 on Cross-cutting Considerations with the accompanying annex 2.

8

1. ABOUT THIS GUIDANCE

The elimination of forced labour and human trafficking is a central challenge for the international

community. Equally, the management of supply chains and their impact on human rights is key to making

progress towards the milestones established in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The 2020 Annual Statistics Report on United Nations Procurement highlights that collectively the 39 UN

Organizations which report procured goods and services (including works) totalling USD $22.3 billion. The

scope of goods and services purchased by UN Organizations varies widely, ranging from health and medical

equipment, food and farming, transportation and storage, IT and communications equipment, to a multitude

of different services. It additionally covers large scale infrastructure projects, the commissioning of niche

scientific testing equipment, the buying of common goods (such as stationery, furniture, and internet

services), as well as goods and services procured during emergencies.

Through its procurement, the UN can encourage and influence sustainable business practice and contribute

to the prevention of forced labour and human trafficking in its supply chain. As large consumers, UN

Organizations have the purchasing power to (i) set standards that encourage businesses to further respect

human rights, (ii) promote accountability, and (iii) support remedy for victims. Recognising this, in 2017 the

UN Security Council called upon United Nations system organizations to enhance transparency in their

procurement and supply chains and step up their efforts to strengthen protections against trafficking in

persons in all United Nations procurement.

This Guidance identifies how the risks of forced labour and human trafficking in UN supply chains can be

addressed across the different stages of the procurement cycle from policy, planning, and tendering through

to contract management. It provides a practical guidance to all UN staff on how to identify and take action on

forced labour and human trafficking in UN supply chains, supplemented by good practice examples of how

UN Organizations and others are currently addressing these issues.

The Guidance is part of the Policy Framework to Combat Forced Labour and Human Trafficking in UN Supply

Chains.

9

• In this section you can find an introduction to the issue of forced labour and human trafficking, the

concept of human rights due diligence, and how the work on addressing forced labour and human

trafficking links to UN procurement objectives and values.

Background and concepts

• In this section you can find guidance on how

to address forced labour and human

trafficking in the UN procurement cycle.

Addressing forced labour and human

trafficking in the procurement cycle

• There are several considerations which are

relevant across the whole procurement cycle,

at multiple stages. In this section you can find

further guidance on these considerations.

Cross-cutting considerations

• In the annexes you can find several useful resources, including: Glossary of Terms, Additional Guidance

on Reporting, links to additional resources, and case studies from UN Organizations.

Annexes

Green boxes are policies, -

procedures and practices that

apply to all UN Organizations

Blue boxes are policies,

procedures and practices of

specific UN Organizations

Yellow boxes are policies,

procedures and practices from

other sources

Pink boxes include reference

to the most recent versions

other elements of the draft

Policy Framework to Combat

Forced Labour and Human

Trafficking in UN Supply

Chains

1.1 Structure and logic of the Guidance

This Guidance is structured as follows:

N.B. use the colors above to navigate in this Guidance. Each page of sections of the Guidance has borders

that are the same colors as indicated above.

Throughout the document text boxes have been included that provide the following content:

1.2 Who should use this Guidance?

This Guidance can be used by UN staff in different roles across the UN system. Given the specificities of each

UN Organizations’ procurement needs, the Guidance outlines a general approach intended to be relevant to

all.

UN Organizations may have their own institutional frameworks, policies, and/or requirements to address

human trafficking and forced labour in their supply chains. The suggestions and examples outlined in this

10

Guidance document are designed to be considered by Organizations when developing their own institutional

frameworks.

Considering the content of the full Guidance is recommended in order to gain a comprehensive

understanding of the overall issue of forced labour and human trafficking, and where steps to address forced

labour and human trafficking should be taken in the procurement process. That being said, there are certain

elements of the Guidance that may be of more relevance to some staff members due to their role and

mandate in their respective Organizations. The following table provides an overview of how the Guidance can

serve to support activities specific to these roles:

Role

How to use this Guidance

Specific sections of interest

Legal and

compliance staff

– staff with

policy/legal/over

sight/compliance

function of the

Organization as

appropriate

For legal, compliance and/ or oversight

staff, this Guidance can be used to

understand how UN Organizations can

address forced labour and human

trafficking in its supply chains and how

support from such staff could be

relevant in contracting and following-up

on performance and non-compliances.

The Background and Concepts section will provide

insights into the normative frameworks and

expectations on the UN. In addition, several parts of

the section on Addressing Forced Labour and Human

Trafficking in the Procurement Process, in particular

section 3.7 on Contract Provisions and section 3.8 on

Contract Management, will be relevant for legal,

compliance and/ or oversight staff to consider.

Finally, in the Crosscutting Considerations section,

section 4.1 on remedy for victims and survivors of

human rights abuses will also be of relevance to such

staff.

Procurement

staff – staff

responsible for

undertaking the

procurement

function

For procurement staff, this Guidance

provides concrete support and

examples of how to apply existing

procurement processes in a way that

supports efforts to combat forced

labour and human trafficking. Through

the examples and resources given, it can

also inspire new ways of addressing the

issue. Finally, the Guidance can provide

arguments for the prioritisation of

processes and resources to address the

risks of forced labour and human

trafficking in UN supply chains.

While the main source of useful guidance can be

found in the Addressing Forced Labour and Human

Trafficking in the Procurement Process and

Crosscutting Considerations sections, the

Background and Concepts section will also be useful

to procurement staff when seeking to understand

forced labour and human trafficking risks, how due

diligence processes can help identify and address

these risks, and how management of these risks ties

into the broader sustainability commitments of the

UN. This can be useful when discussing resourcing

and prioritisation within the Organization.

Requisitioner/

contract

manager - staff

responsible for

the contract

management

function and/or

budget holder

For the requisitioner/contract manager,

this Guidance can provide insights into

the risks of forced labour and human

trafficking as it relates to contract

implementation, and how to manage

such risks in consultation with

procurement staff.

The Background and Concepts section will provide

useful information on the issue of forced labour and

human trafficking, as well as how this ties into

broader sustainability commitments of the UN. In the

Addressing Forced Labour and Human Trafficking in

the Procurement Process, section 3.8 on contract

management will be especially relevant, however, it

is important to understand that steps to address the

issue of forced labour and human trafficking should

be taken already in the project planning phase.

Policy lead –

Authority

For the policy lead, this Guidance can

provide policy-based arguments for

The Background and Concepts section will further

clarify the issue of forced labour and human

11

responsible for

establishing

organizational

and

procurement

policy

Organizations to prioritise combatting

forced labour and human trafficking in

their supply chains. In addition, the

resources and examples provide

inspiration on how to implement

processes to identify, assess and

address risks of forced labour and

human trafficking and how these may

be included in organizational and

procurement policy.

trafficking, the concept of human rights due

diligence, and how these tie into broader

sustainability commitments of the UN. In the

Addressing Forced labour and Human Trafficking in

the Procurement Process and Crosscutting

Considerations sections, the policy lead can get an

insight into the more practical elements of the

procurement process and how considerations on

forced labour and human trafficking can be included.

Human

trafficking and

forced labour

experts – topical

experts within

the organization

in the area of

forced labour

and human

trafficking

For human trafficking and forced labour

experts, this Guidance can be used to

further understand the procurement

process within the UN and where their

expertise can be used and integrated.

This Guidance may also provide

inspiration for these experts in how to

support human trafficking and forced

labour being incorporated into their

organization’s procurement activities.

The Background and Concepts section will provide

insights into the normative frameworks and

expectations on the UN as it relates to procurement.

In addition, several parts of the section on

Addressing Forced Labour and Human Trafficking in

the Procurement Cycle, will be relevant for human

trafficking and forced labour experts to increase their

knowledge of the procurement process and to

support them in identifying where their expertise can

be applied.

12

2. BACKGROUND AND CONCEPTS

Before considering how to address forced labour and human trafficking in the context of UN procurement, it

is necessary to understand the background and key concepts on the issue and the context within UN

sustainable procurement and human rights due diligence. The following sections provide such an

introduction.

2.1 Defining forced labour and human trafficking

Labour exploitation and abuses of human rights are a reality of our current global production systems and

service delivery. Such situations of abuse are often referred to generally as modern slavery or contemporary

forms of slavery. Modern slavery or contemporary forms of slavery as such are not legal terms, however they

are used as umbrella terms to refer to situations of exploitation that a person cannot refuse or leave because

of threats, violence, coercion, deception, and/or abuse of power. According to the International Labour

Organisation (ILO) 40.3 million people are in modern slavery, which includes those in forced and bonded

labour, child labour, victims of human trafficking and those subjected to domestic servitude and forced

marriages. The ILO and UNICEF’s 2020 global estimate on the number of children in child labour highlights

that numbers have risen to 160 million worldwide – an increase of 8.4 million children in the last four years.

According to the ILO, women and girls are disproportionately affected by forced labour, accounting for 99%

of victims in the commercial sex industry, and 58% in other sectors. Illicit profit based on forced labour is

estimated by the ILO in 2014 at USD $150 billion a year.

Forced labour and human trafficking are not confined to isolated countries or sectors, they are universal

issues. They are serious human rights abuses constituting illegal activities in most countries, and

consequently abuses often occur behind closed doors. However, in some cases, especially regarding labour

exploitation, the abuse may be hidden in plain sight.

This Guidance focuses specifically on forced labour and human trafficking, which are defined by a range of

international instruments and authoritative intergovernmental bodies, including the ILO and regional human

rights treaty bodies.

This section aims to clarify the terminology and provide definitions to be used for the purpose of the

Guidance.

Forced labour: The ILO Forced Labour Convention (No. 29) defines forced labour as “all work or service which

is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered

himself voluntarily”. This definition consists of three elements:

− Work or service, which refers to all types of work occurring in any activity, industry or sector

including in the informal economy.

− Menace of any penalty, which refers to a wide range of penalties used to compel someone to work,

for example through restriction of movement, loss of job, or reduction in pay.

13

− Involuntariness, which refers to the lack of free and informed consent of a worker to take a job and

their freedom to leave at any time. Involuntariness may exist, for example, when an employer or

recruiter makes false promises so that a worker takes a job they would not otherwise have accepted.

Although forced labour is often found in the private sector, it can also be imposed by state authorities. The

1957 ILO Abolition of Forced Labour Convention (No. 105) primarily addresses state-imposed forced labour.

This Convention prohibits specifically the use of forced labour:

− as punishment for the expression of political views;

− for the purposes of economic development;

− as a means of labour discipline;

− as a punishment for participation in strikes; and

− as a means of racial, religious or other discrimination.

Human trafficking: The United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons,

Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational

Organized Crime defines human trafficking as:

“the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat

or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of

power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve

the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.

Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms

of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or

the removal of organs.” (see Annex 1 Glossary of Terms for the full definition)

The main elements of this definition are:

− Act: the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons

− Means: threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the

abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits

to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person (it should be noted that the

‘means’ element does not apply to the definition of human trafficking in children).

− Purpose: exploitation, which includes sexual exploitation, forced labour and practices similar to

slavery and servitude, for example domestic servitude and forced marriages, and the removal of

organs.

There are large number of organizations working to combat forced labour and human trafficking which have

produced useful reports on key characteristics or ‘red flags’ to help identify what forced labour and human

trafficking looks like in practice. These indicators are highlighted in section 3.1 on risk identification,

assessment and management and in annex 3 which provides additional resources on risk assessment.

14

terms, UNICEF procured $4,468m compared to the United Nations Assistance to the Khmer Rouge Trials

(UNAKRT) which procured $0.5m.

The UN has over 300,000 vendors registered on the UN Global Marketplace (UNGM) and procures goods and

services from suppliers in over 200 countries and territories around the world operating in challenging

geographies and sourcing from sectors at risk of forced labour and human trafficking. UN supply chains are,

therefore, at risk of instances of forced labour and human trafficking.

The UN is to serve as a role model with the duty to respect international human rights standards and

contribute to the protection of the rights of workers. The values enshrined in the UN Charter of respect for

fundamental human rights, social justice and human dignity, and respect for the equal rights of men and

women are overarching values, which should guide actions to address risks of forced labour and human

trafficking in procurement. The UN commitment to enhancing transparency in UN supply chains and

strengthening protections against trafficking in persons and forced labour is clearly stated in UN Security

Council Resolution 2388, and is reiterated in subsequent resolutions by the UN General Assembly (Resolution

76/7) and the UN Economic and Social Council (Resolution 2021/25).

The UN HLCM-PN has publicly committed to combatting human trafficking and forced labour in UN supply

chains, as expressed in its recent Policy Statement:

The organizations of the United Nations system state their intention and commitment to continue

combating the risk of human trafficking and forced labour in UN supply chains, ensuring the respect of

human rights and exercising due diligence with a human-centered approach.

Answering the call of UN Security Council Resolution S/RES/2388, UN General Assembly Resolution 76/7,

and ECOSOC Resolution 2021/25, we recognize the need to enhance transparency in UN supply chains and

strengthen protections against trafficking in persons and forced labour in all UN activities. We intend to do

so by promoting due diligence and labour standards across UN supply chains, acknowledging this as

fundamental to sustainable development and the overall successful execution of the UN mandate.

We recognize the importance of embedding throughout the UN system measures to combat human

trafficking and forced labour in UN supply chains, while acknowledging the immense challenge of this

complex issue. As such, tackling this problem effectively requires the involvement and contribution of all UN

staff and departments, from policy creation through to implementation.

2.2 UN commitments to combatting forced labour and human

trafficking in its supply chains

Forced labour and human trafficking are prevalent in many supply chains, including those that produce the

goods and services the UN procures. The UN is a large consumer, with 39 UN Organizations collectively

procuring goods and services totalling USD $22.3 billion in 2020. According to the 2020 Annual Statistics

Report on United Nations Procurement, in that year, the 10 largest procuring Organizations accounted for

82.7% of the $22.3 billion procured and the 10 smallest procuring Organizations accounted for 0.4%. In real

15

The UN Supplier Code of Conduct outlines the UN’s expectations of its suppliers to support and respect the

protection of internationally proclaimed human rights and ensure that they are not complicit in human

The approach of the UN to the risks of forced labour and human trafficking in UN supply chains is based on

internationally recognised human rights and ILO International Labour Standards, and is guided by:

− The principles set out in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights;

− The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact;

− The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals;

− The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct;

− The ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles Concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social

Policy; and

− The ILO General Principles and Operational Guidelines for Fair Recruitment and Definition

of Recruitment Fees and Related Costs.

All UN staff must adhere to the UN values as explicitly stated in the Standards of Conduct for the

International Civil Service. As outlined in the Standards, UN values must guide international civil servants in

all their actions and include “fundamental human rights, social justice, the dignity and worth of the human

person and respect for the equal rights of men and women and of nations great and small”. Therefore, UN

staff are bound by these values, including when involved in and responsible for procurement and contracting

activities, and should use the UN procurement function to promote these values.

Specifically, as the UN Procurement Manual states, requisitioners, procurement officials and contract

managers are expected to encourage UN suppliers to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies in

accordance with the UN Supplier Code of Conduct.

We remain committed to addressing the root causes of these challenges, and to working together to

ascertain common approaches that mitigate the risk of human trafficking and forced labour in UN supply

chains.

In this regard, the Procurement Network (PN) pledges its commitment to promote due diligence and

respect for human rights across procurement, legal, programming, and implementation operations, using a

human-centered approach to ensure continual improvement of conditions in UN supply chains.

This objective will be pursued through the adoption today by the HLCM-PN of a system-wide Policy

Framework to Combat Forced Labour and Human Trafficking in UN Supply Chains which includes a

comprehensive Guidance document for UN staff engaged in policy, procurement, and project

implementation with proposed methodologies and contractual clauses based on the best practices evolving

within the UN system.

All United Nations entities are encouraged to incorporate this Guidance into their respective institutional

frameworks and are encouraged to report on progress to the HLCM-PN on a regular basis to allow for

further UN system wide development in this area.

16

2.3 Human rights due diligence and procurement

Human rights due diligence is a risk management process detailed in the UN Guiding Principles on Business

and Human Rights (UNGPs) to operationalise corporate responsibility to respect human rights. It allows a

business (including suppliers to UN Organizations) to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for human rights

impacts that it may cause or contribute to through its own activities, including those which may be directly

linked to its operations, products or services via its commercial relationships. Human rights due diligence

should be supported by measures to facilitate access to an effective remedy for victims where harm has

already occurred. The process of due diligence elaborated in the UNGPs has been incorporated into the

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises

and been further developed by the OECD into ‘Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct’,

which is being used by major businesses to assess and respond to their impact on human rights.

The UNGPs were endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in June 2011 (A/HRC/RES/17/4) and are the first

widely accepted international framework articulating the responsibilities of businesses in relation to human

rights, drawing their authority from pre-existing international human rights laws. Currently, businesses do

not generally have direct legal obligations under international human rights law. Instead, businesses have a

‘responsibility to respect’ human rights, that is, to avoid infringing on the human rights of others and to

address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved. The UNGPs articulate that all businesses

have a responsibility to respect human rights in the context of their own activities and to seek to prevent or

rights abuses. These expectations apply to all suppliers that are registered with the UN or with whom it

does business including their employees, parents, subsidiaries or affiliate entities, and subcontractors.

The Code refers to international labour standards, and addresses the payment of wages, working hours,

health and safety and other working conditions. It also includes a specific clause on forced labour:

5. Forced or Compulsory Labour: The UN expects its suppliers to prohibit forced or compulsory labour

in all its forms.

The Code encourages continuous improvement, and expects that suppliers encourage and work with the

suppliers in their own supply chain to ensure that they also strive to meet its principles.

The Code expects, at a minimum, that suppliers have established clear goals toward meeting the standards

set out in the Code. It sets out the expectation that suppliers will establish and maintain appropriate

management systems related to the content of the Code, and that they actively review, monitor and

modify their management processes and business operations to ensure they align with the principles set

forth in the Code. These principles align with the process of human rights due diligence as set out in the

UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (discussed further in the next section 2.3 on human

rights due diligence and procurement). Supplier participation in the UN Global Compact is strongly

encouraged to operationalise its principles and to communicate progress annually to stakeholders.

Certain provisions of the Code may be binding on a supplier in the event the supplier is awarded a contract

by the UN, depending on the particular terms and conditions of the contract.

17

Human Rights Due Diligence

mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by

their business relationships, even if they have not contributed directly to those impacts. This means that

businesses have a responsibility to take action to respect human rights including in their supply chain and

other business relationships.

In order to meet their responsibility to respect human rights, businesses need to put in place the necessary

policies and processes, including a human rights due diligence process. The implementation of human rights

due diligence can be the single most important contribution by businesses to the realisation of the SDGs.

By undertaking human rights due diligence, an organization can identify, prevent, mitigate and account for

human rights impacts that it may cause or contribute to through its own activities, or which may be directly

linked to its operations, products or services via business relationships. The UNGPs highlight that human

rights due diligence:

- Should cover all potential and actual adverse human rights impacts;

- Will vary in complexity with the size of the business enterprise, the risk of severe human rights

impacts, and the nature and context of its operations - there is not a one-size fits all solution, but

there are common elements in finding a solution;

- Should be ongoing, recognizing that the human rights risks may change over time as the business

enterprise’s operations and operating context evolve; and

18

In annex 4 you can find case studies on how international organizations are applying human rights due

diligence in their procurement activities:

− Case Study 1 – A full procurement cycle approach in practice at the OSCE

− Case Study 2 – Risk management at UNOPS

− Case Study 3 – Social audits at the UNHCR

- Should consider all impacts on human rights, i.e. both impacts that the organization may cause,

contribute to or be linked to through its business relationships and supply chain.

Human rights due diligence is not a tick-box exercise. It requires substantive action, without which the steps

taken risk being labelled as ‘window-dressing’ or ‘green-washing’. Human rights due diligence should be

integrated coherently into existing risk management processes and systems throughout an organization, with

a specific emphasis on the risks to rights-holders and focused on a human-centred approach.

As a part of the human rights due diligence process, organizations should identify their ability to effect

positive change with regards to wrongful practices causing or contributing to a human rights abuse. One

method is to identify and exercise an organization’s leverage over a supplier, intended as the ability to effect

change in a particular context (see Annex 1 – Glossary). While leverage largely depend on the contract value,

it can be enhanced through contractual terms and conditions, as well as supplier engagement, dialogue,

international organization collaboration and collective action to effect change. When it comes to

procurement, leverage can be applied in both the relationship between the buyer and the supplier and by

the supplier towards its own supply chain.

Human rights due diligence is not only useful for business, but also for organizations which undertake

procurement. Introducing forced labour and human trafficking into risk management and procurement

activities is how UN Organizations can conduct human rights due diligence in their supply chains. This

Guidance explains how to introduce human rights due diligence at every stage of the UN procurement cycle

to address the risks of forced labour and human trafficking occurring in UN supply chains. It includes practical

steps and examples of how the UN can exercise its leverage over its suppliers and its supply chain to further

contribute to the elimination of forced labour and human trafficking.

2.4 UN procurement objectives and values

Through its procurement activities, the UN works to achieve a number of strategic objectives on

sustainability, including the protection of the environment, economic and specific social issues, such as

promoting gender equality and disability inclusion. Measures to address forced labour and human trafficking

in UN supply chains should be coherent with sustainable procurement approaches, building from current

measures, benefitting from lessons learned, and effectively adapting these approaches wherever possible.

2.4.1 Sustainable public procurement

In 2015, the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (the

2030 Agenda) as “a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity”. The potential of procurement is

19

highlighted in Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 12. Target 12.7 calls on all states to “[p]romote public

procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities”. The UN High

Level Committee on Management Procurement Network (HLCM-PN) defines sustainable procurement as

“practices that integrate requirements, specifications and criteria that are compatible and in favour of the

protection of the environment, of social progress and in support of economic development, namely by

seeking resource efficiency, improving the quality of products and services, and ultimately optimizing costs”.

Sustainable procurement provides an opportunity to prioritise procurement from suppliers that respect the

three dimensions of sustainable public procurement; economic, social and environmental. Addressing forced

labour and human trafficking is a key step in realising the social element of sustainable procurement. Policies,

tools, and guides to achieve sustainable procurement can provide many useful examples which can be

reproduced, or adapted, to address these violations in UN supply chains.

Procurement exercises can place a focus on procuring from suppliers that have effective measures in place to

prevent and address forced labour and human trafficking, in line with Target 12.7, but also as a means of

realising Targets 8.7 and 16.2 to end child labour, forced labour, modern slavery and human trafficking.

20

Addressing forced labour and human trafficking in UN supply chains is also a means to realise SDG 5 on

gender equality, as women and girls are disproportionately affected by forced labour.

2.4.2 Aligning UN procurement with UN commitments on forced labour and

human trafficking

Through their procurement activities UN Organizations can not only signal their values to the market, but

also support implementation, contributing to shaping business practices worldwide. By requiring their

suppliers to adopt forced labour and human trafficking considerations, UN Organizations can contribute to

developing best practices in this field, while at the same time respecting public procurement principles. In

other words, UN Organizations can and exercise their ability to influence their suppliers and their purchasing

power to contribute to the UN commitments on forced labour and human trafficking.

The procurement process of any UN Organization must respect the existing Financial Regulation 5.12. This

requires giving due consideration to the four general principles of UN procurement: (a) best value for money;

(b) fairness, integrity and transparency; (c) effective international competition; and (d) the interest of the UN.

The introduction of considerations regarding forced labour and human trafficking within the procurement

cycle not only aligns, but supports these principles, particularly the best interest of the UN. The following

sections describe some of the ways they align.

• Best value for money

Best value for money is the overarching procurement aim, found in national, regional and international public

procurement processes. The UN Procurement Manual defines it as “the optimization of the total cost of

ownership and quality needed to meet the user’s requirements, while taking into consideration potential risk

factors and resources available”. As such, this does not necessarily require awarding the contract to the

lowest offer by a supplier, but it allows for the introduction of other parameters, including social

considerations (such as the Sustainable Procurement Indicators, which include addressing forced labour and

human trafficking considerations in UN Supply Chains, see section 3.3 Supplier registration and the UN Global

Marketplace (UNGM)).

21

Best value for money in UN Organization Procurement Manuals

The principle of ‘best value for money’ is described in the Procurement Manuals of UN Organizations in

several complementary ways. A few examples of how manuals make direct reference between best value

for money and social criteria include, among others:

ILO Procurement Manual: ‘Value for money is measured by reference to the needs and interests of the

ILO’ (p. 5). ‘Best value for money may also be assessed by reference to inherent risk factors and any social,

environmental or other strategic objectives of the Organization’ (p. 13).

UNDP Procurement Manual: ‘This definition enables the compilation of a procurement specification that

includes social, economic and environmental policy objectives within the procurement process.’ (p. 14).

UNOPS Procurement Manual: ‘The purpose of public procurement is to obtain the best value for money

and to do this it is important to consider, among other factors, the optimum combination of the total cost

of ownership (i.e. acquisition cost, cost of maintenance and running costs, disposal cost) of a purchase and

its fitness for purpose (i.e. quality and ability to meet the contracting authority’s requirements). This

definition enables the compilation of a procurement specification that includes social, economic and

environmental policy objectives within the procurement process’ (p. 14).

…

‘the implementation of sustainable procurement not only does not hinder, but in fact it supports,

achieving its key procurement principles: best value for money; fairness, integrity and transparency;

effective competition; and best interest of UNOPS and its partners.’ (p. 5)

Forced labour and human trafficking have an important economic impact as well as a devastating human

cost. These abusive practices increase the revenues of transnational organised crime while there are

immense costs to implement policies and services for coordination, prevention, law enforcement, health and

social protection; lost economic output and revenue; and lost quality of life. What may appear as best value

for money on paper may have important hidden costs, not only for a procuring organization but for the entire

global economy.

• Fairness, integrity and transparency

Businesses taking advantage of workers to cut prices runs directly against the principle of fairness which

guides UN procurement. By having requirements of suppliers with regards to forced labour and human

trafficking, the principle of fairness is maintained for bidders competing for UN business opportunities,

including that all rules be clearly defined and applied in an unbiased manner.

The integrity principle requires all UN staff to perform their functions consistent with the highest standards

of integrity as required by the Charter of the United Nations. Integrating considerations to prevent and

respond to forced labour and human trafficking in UN supply chains directly supports the adherence to

ethical standards in UN operations.

By transparency the UN Procurement Manual means that all interested parties have access to relevant

information on procurement policies, procedures, and opportunities. Imposing obligations on bidders and

22

suppliers regarding forced labour and human trafficking contributes to transparency by clarifying, from the

start, that the UN is committed to identifying and addressing incidences of forced labour or human trafficking

in its supply chains. In order to enhance transparency, this Guidance suggests that UN Organizations report

on their actions to prevent and respond to forced labour and human trafficking (see section 4.6 and annex 2

for more information on reporting).

• Effective international competition on a level playing field

A UN wide approach to addressing forced labour and human trafficking in UN Supply chains helps to create a

level playing field for suppliers that strive to respect human rights. Human rights abuses disrupt international

competition. Fostering effective competition on a levelled playing field requires that suppliers to UN

Organizations do not benefit from forced labour and human trafficking, for example, to provide lower prices

or faster delivery conditions.

• Best interest of the UN

Addressing forced labour and human trafficking in UN supply chains is in the best interest of UN

Organizations: it is part of the values of the Organization and protects it from reputational risks. UN

Organizations should utilise procurement to require their suppliers to address the risk of human rights

violations, including by supporting suppliers to identify and respond to such human rights abuses.

• Cooperation and collaboration

Whilst cooperation and collaboration are not listed in the UN Procurement Manual as procurement principles

per se, they underpin the whole procurement process and are key for the development of procurement

activities. The UN Procurement Manual clearly states that cooperation in procurement among UN

Organizations can result in significant benefits due to economies of scale, reduced transaction costs, agility

and improved relations with suppliers (Chapter 14). This includes cooperation with UN Organizations as well

as non-UN organizations and with governments.

The 2020 Annual Statistics Report on United Nations Procurement notes that 34 of the 39 UN Organizations

which report engaged in collaborative procurement. Furthermore, there is a range of good practice examples

of how forced labour and human trafficking are currently addressed by UN Organizations. However, there is

still room for increasing cooperation. As the 2019 report by the OECD, The International Organization for

Migration (IOM) and UNICEF on Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply

chains states, “there is a need for greater international collaboration around responsible public procurement

in order to share learning and best practices, and to exchange tools and information on risks related to

certain products and markets and on follow-up and monitoring.”

It is important that good practice, challenges, and lessons learned are shared within and among UN

Organizations to promote a coherent approach and maximise synergies where they emerge, in line with the

UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework and the UN SDG Business Operations Strategy.

23

Sharing within the UN

The High-Level Committee on Management – Procurement Network (HLCM-PN) was established in April

2007. The Network’s mandate is to promote the strategic role of Procurement and Supply Chain

Management in programme and service delivery in a transparent and accountable manner. As of

September 2020, representatives from 40 organizations were members of the Procurement Network. The

Network is responsible for the UN Global Marketplace and works to improve the efficiency and

effectiveness of the procurement function within the UN System through working groups on:

- Harmonization

- Professional Development

- Sustainable Procurement

- Strategic Vendor Management

- Cognitive Procurement

The HLCM-PN liaises with other networks in the HLCM, including the Legal Network.

The Inter-Agency Coordination Group against Trafficking in Persons (ICAT) is a policy forum mandated by

the UN General Assembly to improve coordination among UN Organizations and other relevant

international organizations to facilitate a holistic and comprehensive approach to preventing and

combating trafficking in persons, including protection and support for victims of trafficking. As of

December 2021, ICAT had a membership of 30 UN entities and other international and regional

organizations.

The Common Procurement Activities Group (CPAG) is a voluntary inter-agency procurement network

composed of 20 Geneva-based UN and international organizations, which the UNOG is the Secretary of.

The objective of CPAG is to provide additional value and collaborative ideas to procurement activities in

order to achieve best value for money, not only in the solicitation process but also in the day-to-day

procurement functions, by identifying cost efficiencies and collaborative solutions to procurement

challenges. More info can be found in the 2020 CPAG annual report.

24

3. ADDRESSING FORCED LABOUR AND HUMAN TRAFFICKING

IN THE PROCUREMENT CYCLE

This section highlights measures to be taken relevant to the different stages of the procurement cycle in

order to exercise human rights due diligence in UN procurement, meaning: to identify, prevent, and mitigate

risks of forced labour and human trafficking in the UN supply chain. This should be read in conjunction with

section 4 on Crosscutting Considerations.

The section is structured to follow the procurement cycle, but all the measures detailed should be considered

already at the procurement planning stage.

Familiarity with the UN Procurement Manual and the UN Procurement Practitioner’s Handbook is advised

before reading further.

When addressing forced labour and human trafficking in UN supply chains (and throughout the procurement

cycle), the following key actions can be taken:

1. Learn what forced labor and human trafficking risks look like and conduct relevant research when

undertaking a risk assessment. Look as far down the supply chain as possible, and assess this risk based

on the severity of impacts to people using a human-centred approach. For more on risk identification,

assessment, and management see section 3.1 on risk identification, assessment and management.

2. Consider obtaining information (through surveys, interviews and other means) on how suppliers

currently address forced labour and human trafficking in the given market to assess the level of maturity

of the suppliers and the broader market. This can help identify the level of maturity of suppliers in the

operating context and accordingly, what level of requirements with respect to forced labour and human

trafficking should be introduced. For more on gathering information including through supplier

engagement, see sections 3.2 on sourcing and 4.2 on supplier engagement and support.

3. Design requirements and evaluation criteria to address identified risks of forced labour and human

trafficking, and:

a. Consider how to score or make mandatory these criteria, where possible

b. Consider how to turn requirements into performance indicators to monitor compliance

For more on designing requirements and criteria see section 3.4 on requirements definition.

4. Consider how to communicate new requirements to suppliers through the tender and during

contract implementation and provide supplier support in their efforts to address forced labour and

human trafficking. See sections 3.8 on contract management and 4.2 on supplier engagement and

support.

5. Identify, and where relevant consider establishing, a mechanism to receive complaints of forced labour

and human trafficking abuses in supply chains, as well as a process to verify and address the abuses. See

sections 3.10 on actions to take when a forced labour or human trafficking issue arises and section 4.1 on

remedy for victims and survivors of human rights abuses.

25

An example of UN cooperation in addressing risk management

Existing risk management procedures can also provide guidance on how to apply human rights due

diligence to relationships with external actors, including partnership and lending relationships.

For example, the UN Implementing Partner PSEA Capacity Assessment was published in September 2020

and provides a common baseline for UN funds, Agencies and programmes to have the necessary assurance

of partners’ organizational capacities on Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Abuse, and includes:

(1) partner self-assessment;

(2) UN entity review and preliminary determination of partner capacity;

(3) documented decision including capacity-strengthening implementation plan;

(4) appropriate monitoring and support activities; and

(5) final determination of partner capacity.

3.1 Risk identification, assessment and management

Identifying and assessing risks of forced labour and human trafficking in UN supply chains is a vital first step in

exercising human rights due diligence and addressing such risks. Once risks have been identified and

assessed, appropriate measures to encourage supplier respect for human rights can be defined and included

at different stages of the procurement cycle to try to prevent and/or mitigate risks of forced labour and

human trafficking becoming realities. This section provides guidance on identifying forced labour and human

trafficking risks (section 3.1.1) and assessing and mitigating such risks (section 3.1.2).

In this case, the risk focus should not be exclusive to large scale, high spend procurements, as monetary value

is not directly related to the risk of forced labour and human trafficking. Risks of this nature are dependent

on a multitude of factors, including industry and commodity/service type, supply chain complexity,

geographical spread, and workforce composition.

Risk identification and analysis for forced labour and human trafficking should ideally be conducted for every

procurement exercise or groups of similar purchases/markets, although the measures to respond to the risk

will naturally vary depending on the value of the procurement and risks identified. Since UN Organizations

may not have the capacity to address all risks at once, a risk assessment can also help decide what to

prioritise. It should be noted that human rights risks vary with changing circumstances on the ground and the

results of risk assessment processes will require periodic updating.

Several UN Organizations already undertake extensive risk management procedures related to human rights,

managing risk at many levels, including outcome level, country level, and project level. Procurement does not

take place in isolation and risk management at these upstream levels should lay the groundwork for

procurement-level risk management.

UN Organizations can, as and where appropriate, pool their resources to undertake joint risk assessments.

Where possible, UN Organizations should share and provide access to information, including risk

assessments, to UN Organizations and other organizations.

26

3.1.1 IDENTIFYING FORCED LABOUR AND HUMAN TRAFFICKING RISKS

A risk assessment is only as thorough as the information gathered. Key elements to consider when identifying

forced labour and human rights risk include:

- Knowing what risks to look for;

- Reliable sources of information;

- Supply chain mapping;

- Identifying related risks; and

- Adopting a life-cycle approach.

• Knowing what risks to look for

When identifying what forced labour and human trafficking looks like on the ground, a series of questions

can help guide a risk assessment. The questions listed below are only indicative, which means that a positive

answer does not equate necessarily to the existence of forced labour and human trafficking but, in

combination with the other elements of this section, they provide grounds to further consider whether

workers may be subject to abuse. As supply chains can cross borders, the questions below should be asked of

the country where the supplier is based, the country where the activities occur, and other countries known to

be in the related supply chain.

Country risk factors

- Has the country ratified relevant international instruments? Are there reports on the country failing to

implement international instruments it has ratified (e.g. reports part of the Universal Periodic Review

Process; communications from UN Treaty Bodies, national human rights institutions reports, civil society

organizations reports)?

- Are freedom of association and collective bargaining protected under national laws? Do national legal

regimes outlaw peaceful strike action? Are trade unions able to operate without interference?

- Does the country operate state-orchestrated programmes involving:

o Forced labour of administratively detained persons, prisoners in pre-trial detention, political

prisoners, persons detained for trade union activity or peaceful assembly?

o Mass mobilisation for large-scale national development programmes?

o Labour and/or vocational programmes targeted at persons belonging to minorities?

- Are there challenges conducting in-depth risk assessments in the national context, for example through

threats or enforced presence of government/employers or intimidation of human rights defenders?

- Is the country on either end of a labour migration corridor?

- Is the country ranked in the lower end of relevant indices, including, for example:

o Global Rights Index

o Fragile States Index

Working conditions risk factors

27

- Are there any concerns about the treatment of workers, including fair pay and working hours?

- Do workers appear to work or live in isolation? Are worker movements restricted by their employer?

- Are there concerns regarding the health and safety of workers, due to the nature of their job? Is it

possible to verify if safeguards have been implemented?

- Is there an absence of written employment contracts? Are indirect employment relationships favoured?

- Are workers subjected to intimidation and threats, physical and sexual violence, abusive working and

living conditions, excessive overtime and very low pay?

- Does the workplace rely on “labour discipline” for production, i.e. an obligation to work as a sanction for

violating company rules or failing to complete production quota?

Migration, informality or other vulnerable worker risk factors

- Is there a high proportion of migrant workers? Are they recruited through agencies? How regulated are

these agencies?

- Is there a high proportion of informal workers?

- Are worker accommodations provided by the employer?

- Could employers be taking advantage of specific vulnerabilities, such as migrant worker status, asylum

seeker or refugee status, irregularities in legal status, or social or personal circumstances, which restrict

their ability to change employers, to move within the country or to leave the host country without

permission of their employer?

Recruitment and debt risk factors

- Are workers getting their wages directly or are they subject to the use of irregular, delayed, deferred or

non-payment of wages as a means to bind them to their employment?

- Are there restrictions on the ability of workers to freely dispose of their wages (e.g. a disproportionate

portion of their wages is deducted for accommodation, uniforms, etc.)?

- Are wages being withheld in order to pay debts the worker has incurred during the recruitment process?

- Have workers been recruited with deception or other abusive or fraudulent means, including being

subject to recruitment fees and associated costs?

- Have workers’ identity and/or residency documents been withheld during the recruitment process or

during employment?

• Reliable sources of information

Many UN Organizations undertake extensive risk assessments at the country level and project level and these

risk registers. In addition, a large number of UN Organizations have projects and experts working directly on

forced labour and human trafficking at the country level. These colleagues can be a valuable source of

information to identify risks specific to a product or service, supply chain or industry. Annex 3 lists further

sources of information for risk identification and assessment, including sources from UN Organizations,

member states, non-governmental organizations, and the media.

28

Utilising potential suppliers as a source of information

In Yemen, the UN Office for Project Services (UNOPS) undertook a tender for waste management, an

environment where there were known human rights abuses such as child labour. To get a more in-depth

understanding of the local environment and associated risks, UNOPS undertook a data collection exercise

with stakeholders, including potential bidders. Potential bidders were assured that these sessions were not

intended to evaluate or shortlist them, but were purely a data gathering exercise. A risk register was

created and categorised according to different topics including safeguarding and the environment. The

register was then included in the overall UNOPS risk management system (see annex 4, case study 2 on

sustainable procurement at UNOPS).

Engagement with suppliers, local communities, trade unions, and workers’ groups can also provide useful

information on the types of risks specific to a certain supplier or factory especially in certain countries,

markets, or sectors, where it may be difficult to source relevant information on forced labour and human

trafficking from a desk-based exercise to inform a risk assessment. This can be conducted through

questionnaires, group interviews, conferences, or other events. Engagement with suppliers can help

understand supplier maturity and help to determine what may be reasonable expectations from suppliers

throughout the procurement process (see section 3.2 on sourcing and section 3.5 on supplier qualification to

find more details on the use of supplier questionnaires).

• Supply chain mapping

Supply chain mapping is a very useful method to identify and understand the risks that may arise or already

be present in supply chains. It should aim to create a map of the different supply chain tiers, across different

industries, sectors, and countries, and map relative characteristics and vulnerabilities. Understanding

different parts of a supply chain, the entities involved and the countries where they are located, is vital to

address risks thoroughly.

Global supply chains can be vast, complex and dynamic, and accordingly mapping the supply chain beyond

Tier 1 is challenging. A mapping exercise should begin with the higher tiers, moving into lower tiers as the

process is developed further. Market research (see section 3.2 on sourcing) and tendering criteria requiring

suppliers to preliminarily disclose certain pieces of information can be a helpful source of information in

developing a better understanding of a supply chain in a sector (see section 3.4 on requirements definition

and 3.5 on supplier qualification). Suppliers will have much more visibility over their supply chains than UN

Organizations. Equally, supply chains are dynamic and will change over time. Therefore, an effective mapping

exercise should continue after the award of a contract, and should involve the input and collaboration of the