Art and Design Review, 2020, 8, 114-126

https://www.scirp.org/journal/adr

ISSN Online: 2332-2004

ISSN Print: 2332-1997

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 May 12, 2020 114 Art and Design Review

Requiem: Psychological, Philosophical, and

Aesthetic Notes on the Music of the Mass for the

Dead

—Dedicated to the Victims of COVID-19 Worldwide

Vladimir J. Konečni

Department of Psychology, University of California, San Diego, USA

Abstract

The article discusses the musical, psychological, philosophical and aesthetic

essence of the Latin

Requiem

, the

Missa pro defunctis

, the Mass for the Dead.

It examines in particular detail the famous Sequence

Dies irae.

Numerous

Requiems

up to the most recent ones are discussed and compared. Concepts

from empirical aesthetics of Berlyne (1971, 1974) and Konečni (1979, 1982)

are used to analyze the relationship between the hypothetical “power”

of parts

of the Mass (in psycho-aesthetic terms) and its effect on listeners. Historical

reasons are examined for the difference in approaches to music for the ser-

vices for the deceased between Western and Eastern Christian Churches (es-

pecially with regard to the use of instrumentation).

Keywords

Requiem Music, Requiem and Emotions,

Dies irae

, Mass for the Dead,

Psychology of the Mass, Philosophy of the Mass, Aesthetics of the Mass,

Orthodox Christian Liturgy, St. John of Damascus, St. John Chrysostom

1. Mass for the Dead—Preliminaries

Requiem aeternam dona eis Domine

—Grant them eternal rest, O Lord. The very

first line of the Roman Catholic

Missa pro defunctis

(Mass for the dead) implies

a web of relations between the living supplicant(s), the deceased potential reci-

pients of the extraordinary favor requested, and a hopefully beneficent God. The

five Latin words contain implicit references to grief, fear, and hope, and thus to

the most profound philosophical and psychological questions of human exis-

How to cite this paper:

Konečni, V.

J.

(20

20).

Requiem

: Psychological, Philosophi-

cal, and Aesthetic Notes on the Music of the

Mass for the Dead

.

Art and Design Review

,

8

,

114-126.

https://doi.org/10.4236/adr.2020.82008

Received:

April 23, 2020

Accepted:

May 9, 2020

Published:

May 12, 2020

Copyright © 20

20 by author(s) and

Scientific

Research Publishing Inc.

This work is

licensed under the Creative

Commons Attribution International

License (CC BY

4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Open Access

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 115 Art and Design Review

tence. Why were we put in this world if we must die? Is there another side?

What will happen there? Can we hope finally to obtain peace? These are ques-

tions of deep contemplation and emotion, but also, in regard to the quality of the

music through which ideas are expressed, also of musical aesthetics.

The word “requiem” refers to a musical form; it is a shorthand for the Mass

for the dead, in the singular or the plural, performed for someone who has just

died, or did so long ago, or who will die, usually soon. Note that in “

Requiem

…

dona

eis

Domine” the word “requiem” is in the fourth grammatical case (the

accusative

), and that “eis” means “them”, so that the humble request is to give

(eternal) rest to

them

not to us.

In this sense, the mental stance of a relatively

small number of composers who wrote requiems to be performed at their own

funerals is somewhat incongruous. Nevertheless, this was almost certainly the

intent of Luigi Cherubini (1760-1842) in his second Requiem, in

D minor

(1836), as well as of Charles Gounod (1818-1893) in his Requiem in

C major

(

opus posthumous

). On the other hand, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s (1756-1791)

unfinished Requiem in

D minor

, and, for example, Franz Liszt’s (1811-1886) aus-

tere Requiem (1871) for organ, tympani, and four male voices, in the archaic

Roman style recalling Giovanni da Palestrina (c. 1525-1594), are often placed in

this category erroneously (Cormican, 1991; Merrick, 1987). In any case, the act

of composing an elaborate, lengthy piece for one’s own funeral illustrates the

enormous seriousness with which many musicians have regarded this musical

form.

Almost invariably, composers who undertook the task of writing requiems,

especially in the 18th and 19th century, were already very famous and did so at

the peak of their creative powers. They were men mature as both musicians and

human beings, who had experienced grief, joy, pain, and both the dashed and

the rekindled hope. The Requiem Mass, more than any other musical form, ex-

plicitly deals with spirituality and metaphysics; thus a composer who has expe-

rienced the complexities and vagaries of life may have been more likely to have

deeper sources of understanding and psychological inspiration from which to

draw (cf. Abra, 1995).

2. The Context of Dying: Respect for the Deceased and for

One’s Ancestors

A vast proportion of peoples on our planet, from Australian Aborigines,

Amazon indigenous tribes, and Inuits on three continents, to contemporary

Christians, Moslems, and Buddhists, all earnestly and publicly honor their an-

cestors. “Ancestor worship” is one of the first concepts that students of anth-

ropology encounter. In many societies, paying homage to the dead culminates

on a particular day of the year. Among Christians, both East and West, this is

the All Souls Day; in Japan, the O’bon festival; in China, the Qingming festival

(Tomb-Sweeping Day).

Worldwide, the respect for the deceased is often mingled with a certain degree

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 116 Art and Design Review

of fear, of insecurity, of soul-searching. The fear is not just of death itself, but of

uncertainty, even among the highly educated, about the possible “other side”.

The best educated realize that the magnificent Dante Alighieri of the

Divina

Commedia

(1320) was no fool. At key life moments, doubt does not spare even

the most intellectually atheistic or agnostic or self-assured. And then: can one

annoy ancestors by one’s behavior—with dire consequences? Fears of insulting

ancestors are especially strong in the Voodoo culture in Haiti, and the related

Vodun beliefs in Bénin (formerly Dahomey) in West Africa. But they are not

alone!

To return to the

requiem

as a musical form: To understand what it represents

in the most general sense, one has to consider it as a

unique

totality

of

instru-

mental

and

vocal

sound

that inexorably relates the composer, the performers,

and the listeners (at home, in a church, or concert hall) to the entire complex

context of finality, of passing away, of the deceased (who have sometimes so re-

cently been alive), of the unknown and the unknowable—a profound philo-

sophical, psychological, and emotional enigma explored through something tri-

vially called music

.

The context of dying—whether one thinks of it in the abstract, or watches

someone’s agony, or experiences one’s own, as one mourns, grieves, and fears—is

so emotionally taxing, and so thoroughly captured in the text and

plainchant

(or

plainsong

, Gregorian chant, such as is still sung by the Benedictine monks of the

monastery of St. Pierre de Solesmes near Le Mans in France) as part of the Re-

quiem Mass, that one is tempted to go on a limb and say that the crux of this

music for the departed, the dead, is incredibly simple: If one cannot be moved by

it, one can hardly be alive.

3. Mass for the Dead—Ancient Origins

According to Alec Robertson (1968): “The origins of prayers to and for the dead

that were to lead, over nine centuries, to the

Missa

pro

defunctis

, are to be found

in the [Roman] catacombs, the underground cemeteries of the early Christians.”

In Robertson’s work one can find transcriptions of a number of pertinent and

penitent “graffiti” from the catacombs.

Here are some historical points from various insufficiently identified sources:

– “Memento for the dead” in the

Kyrie

Litany

from the 5th century, which is

the first reference to the dead in the Mass;

– In the Canon, the most solemn part of the Mass, from the 7th century, there

is a prayer for the living and the dead, just before the consecration of bread

and wine:

“Remember also, O Lord, Thy servants, N & N, who have gone before us with

the sign of faith and who rest in the sleep of peace.”

And then, from about the 10th century, one can speak of a specific

Requiem

Mass

. From various sources, some unreliable, others impossible to trace, one

learns roughly the following: The Mass for the Dead is of Franco-Gallican origin.

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 117 Art and Design Review

Charles I, Charlemagne, the first Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, crowned

in Aachen in the year 800, imposed the

Gregorian

Antiphonale

on the Franks,

but supplemented it with liturgy books already in use in France. By the 10th

century, the so-called Roman liturgy returned from Franco-Germanic lands to

Rome, having undergone many changes.

4. Liturgical Structure of the Requiem Mass

The full text of the Latin

Requiem

Mass

reflects various psychological complexi-

ties and contains parts of

ordinarium

missae,

parts of

proprium

missae

, and

important parts that are unique to it.

Ordinarium

Missae

includes texts that are

the same for every (daily) Mass, sung by the choir or the congregation; this ma-

terial attracted many composers. Its parts are:

Kyrie

;

Gloria

;

Credo

;

Sanctus

et

Benedictus

;

Agnus

Dei

.

As for

Proprium

Missae

, items vary according to a Saint’s Day or season of the

year; they have not attracted composers for obvious reasons—they would be

rarely performed. Its parts frequently are:

Introitus

;

Graduale

;

Alleluia

(or

Tract

;

4th C., Eastern Christian churches);

Sequentia

;

Offertorium

;

Communion.

The

first significant settings of the

Proprium

Missae

are thought to be those of Guil-

lermus Dufay (1402-1474) around 1430.

Missa

pro

defunctis

formally belongs to the

Proprium

category but it can be

performed at any time—it is not bound by the Church calendar. Here are the

essential parts of the

Requiem

Mass

:

Introitus

(Processional chant, 9th C.)

Kyrie

eleison

(“Lord, have mercy upon us”)

Graduale

(A chant; 4th C.)

Tractus

(Used here instead of the joyous

Alleluia

; continuous structure with-

out refrain)

Sequentia

(

Dies

irae;

13th-14th C.)

Offertorium

(Bread and wine are ceremoniously placed on the altar; 9th-11th

C.)

Sanctus

et

Benedictus

(Acclamations: “Holy, Holy, Holy”; and: “Blessed is he

that cometh in the name of the Lord”)

Agnus

Dei

(“Lamb of God”, a prayer to Jesus)

Communion/Eucharist

(Partaking is done in remembrance of the body and

blood of Jesus)

Many polyphonic requiems omit some of the above. For example, the

Re-

quiem

by Johannes Ockeghem (c. 1410-1497), the earliest surviving polyphonic

setting (1463?), lacks

Sanctus

and

Agnus

Dei

. Others add parts: as just one

well-known example, Giuseppe Verdi’s (1813-1901)

Requiem

(1874) ends with

the responsory

Libera

me

from the burial service that follows the Mass. Charles

Gounod added

Pie

Jesu

, while Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) added both

Pie

Jesu

and

In

Paradisum.

The contemporary Russian composer Vyacheslav Artyomov’s

(b. 1940)

Requiem

(composed 1985-1988) is perhaps the most complete one,

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 118 Art and Design Review

with fifteen sections, including

Libera

Me

,

Pie

Jesu

, and

In

Paradisum.

In addition to the previously mentioned requiems [Ockeghem, Mozart, Che-

rubini (two), Gounod, Fauré, Verdi, Liszt], there are other well-known ones,

such as by Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) in 1837, Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) in

1890, Max Reger (1873-1916) in 1915, Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) in 1960,

György Ligeti (1923-2006) in 1965, and Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998) in 1975.

Readers should be reminded of composers who would have been excellent

candidates for writing requiems but did not. All, however, wrote profound Ro-

man Catholic music: Haydn (

Seven

Last

Words

of

Christ

on

the

Cross

); Beetho-

ven [

Mass

in

C

major,

Mass

in

D

major

(

Missa

Solemnis

)]—and he is known to

have said (Deane, 1981) that if he were to write a

Requiem

, Cherubini’s would be

his model (referring necessarily to Cherubini’s first

Requiem,

in

C

minor

, per-

formed in 1817, ten years before Beethoven’s death); G. Rossini (

Stabat

Mater

);

K. Szymanovski (

Stabat

Mater

); A. Honegger (

Symphonie

No.

3 “

Liturgi-

que

”—instrumental, but with movements entitled

Dies

irae,

De

Profundis,

Do-

na

Nobis

Pace

); O. Messiaen (

Nativité

etc.); and A. Pärt (b. 1935;

Te

Deum

etc.;

he may yet compose a requiem!). This list does not include Palestrina, Orlando

di Lasso, and other great 16th C. composers of music for the Church.

Finally, for this section, one should be reminded of compositions carrying the

name “Requiem” but which are not Roman Catholic

Missa

pro

defunctis.

There

is, for example, Johannes Brahms’s (1868)

German

Requiem

, based on the Lu-

theran Bible; Benjamin Britten’s (1962)

War

Requiem

, set to poems by Wilfred

Owen; and there is Dmitry Kabalevsky’s (1963)

Requiem

for

those

who

died

in

the

war

against

fascism.

There are also about thirty little-known, mostly

non-religious, works with “Requiem” in the title, written in the 20th C. by

American composers (DeVenny, 1990). Many are doctoral dissertation works.

Perhaps the best known is the 28-minute

Poets

’

Requiem

(1955) by Ned Rorem,

with movements

Kafka

,

Rilke

,

Cocteau

,

Mallarmé

, etc.

5. Dies irae, Dies illa

One must dig deeper into the structure of the Requiem Mass and examine the

Sequentia

Dies

irae

,

dies

illa

(“Days of wrath, days of sorrow”) to find the section

most uniquely associated with the

Missa

pro

defunctis.

This sequence entered

the Mass in the 13th or early 14th century. The author (perhaps Tomasso da Ce-

lano c. 1185-c. 1265), “drew his inspiration from the responsory

Libera

me,

Do-

mine,

de

morte

aeterna

, sung in the

Absolution

at the end of the Mass”, but its

origin can perhaps be traced to the Vulgate Bible, with Prophet Zephaniah’s (in

the 7

th

century BC) “stern call for repentance and the abolition of idolatry,” al-

though he ends “with the ‘Song of consolation’” (Robertson, 1968: pp. 15-16).

Hellfire and forgiveness, stick and carrot.

Dies

irae

is not a part of either the

ordinarium

or the

proprium

missae

, and

has no equivalent in the Eastern Orthodox Mass for the Dead (St. John of Da-

mascus, 675-749) or in other music specially composed for the Orthodox burial

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 119 Art and Design Review

(e.g.

Opelo

, 1883, of the Serbian composer Stevan Mokranjac, 1856-1914).

Robertson (1968: p. 17) states that “the enormous popularity of

Dies

irae

does

not justify … its presence in the Requiem Mass”, but fails to justify this view.

After all, Franz Liszt is quoted by Merrick (1987: p. 140) as exclaiming in its fa-

vor: “Despite the terrors of

Dies

irae

…” My view is that in

Dies

irae

one has a

mixture of God’s anger that we have sinned and fallen from grace, thus forcing

Him to make us die, and of our own anger at living a life with the knowledge of

the imminence of death. Add to that the pain of witnessing the suffering and

death of our loved ones (and even of our enemies?), and one has a very hot and

bitter brew indeed. If one is a believer, the sorrow about what

could

have

been

is

present alongside the anger and the pain, all these powerful emotions rising and

subsiding, evoked and accompanied by the text and the music.

Dies

irae

is in-

deed a multi-faceted, turbulent structure full of arousal-raising possibilities, one

of the most important emotional centers of the

Requiem

Mass.

It predicts the

horror of the Last Judgement together with prayers for salvation on that day.

The essential truthfulness of the claims in the preceding paragraph can be il-

lustrated by the profound effect of

Dies

irae

on a prominent classical music crit-

ic, Basil Deane. Writing about Cherubini’s first

Requiem

in

C

minor

(1817), he

states: “The short

Graduale

ends in a quiet atmosphere on a sustained

G

major

chord. Then the silence is shattered by a clangorous outburst from the brass,

followed by a thunderous stroke on the gong. The

Dies

irae

has begun and we

are transported from a world of cloistered contemplation to that of Dante’s

In-

ferno

” (Deane, 1981). And in regard to Cherubini’s second

Requiem

(in

D

mi-

nor

, 1836): “The

Graduale

is entirely unaccompanied, an unusual treatment…

But the opening bars of the following

Dies

irae

show that Cherubini had a spe-

cifically dramatic purpose in mind. For the first time in the work the violins en-

ter with a surging figure that culminates in a great outburst by voices and or-

chestra to the opening words of the poem. From then on, the music moves with

overwhelming impetus, illustrating precisely and succinctly each phrase of the

vivid text” (Deane, 1979).

1

The poem is written in trochaic metre, each line of each of the eighteen

three-line stanzas having eight syllables; the lines are rhyming. Here are a few

stanzas: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 8th, 9th, and 16th. As for the English translation, it is giv-

en by Robertson (1968: p. 17) as coming from “a

Manual

of 1673, and is perhaps

by J. Austin (d. 1669).” One also finds in Robertson (1968: p. 17) the following

statement: “According to John Julian’s

Dictionary

of

Hymnology

(1892) there

were at that time over 150 English translations of the Sequence, and several have

been added since.”

1

In this article, when discussing the effects on listeners of the

Requiem Mass

and of the

Dies irae

,

“emotions” are frequently mentioned. It is essential to note that this does not in any sense imply

support for the erroneous claims in the “music-causes-emotion” literature that

absolute music

may

give rise to listeners’

fundamental emotions.

The

Requiem Mass

, or any

Mass

, is not absolute music.

It contains text that is sung and numerous non- or extra-musical meanings. The entire context, si

g-

nificantly beyond the

instrumental sound

alone is one of

sadness—

and perhaps hope

(Kivy, 1990;

Konečni, 2008, 2013).

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 120 Art and Design Review

A few brief words about how different composers dealt with the

Dies

irae.

Mozart has two repeats of the first two stanzas. But according to Wolff

(1991/1994: p. 96), “Mozart’s starting point in the selection of his principal key

[

D

minor

] was, we may be certain, the Dorian mode of the Sequence’s ‘Dies

irae’, which thus comes to impress itself decisively on the entire Requiem, even if

the medieval melody associated with the mode is never actually heard.” Liszt and

Dvořák address the first three stanzas (including

Tuba

mirum…

). Gounod in-

terferes with the metre: The first two lines of the first stanza, then their repeat,

then the third line. Verdi deals with the text operatically, Reger in the Late Ro-

mantic style. Honegger’s instrumental

Dies

irae

lasts only 21 seconds. Artyo-

mov’s tremendous

Dies

irae

lasts 7 minutes and 28 seconds, about one-tenth of

the length of his entire

Requiem

, and thus is both in absolute terms and propor-

tionately the longest such section in any Requiem.

6. Relevant Principles from the Psychological Aesthetic

Analysis

The following discussion stems from a branch of psychology called

empirical

aesthetics

, and specifically from the work of the eminent psychobiologist and

aesthetician Daniel E. Berlyne (1924-1976), and of the present author, one of

whose doctoral mentors at the University of Toronto (1970-1973) was Professor

Berlyne. The sources in question are Berlyne (1971, 1974) and Konečni (1979,

1982, 2015).

With regard to the analysis of works of art, including music, it is useful to dis-

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 121 Art and Design Review

tinguish three categories of variables, that is, three categories of attributes or

properties that any work of music and visual art possess (examples are from mu-

sic):

Psychophysical

properties: dynamic range, instrumentation, timbre, mode,

tempo, use of voice, etc.

Referential

(or “meaning”) properties: associations that are made through text

and sound to the existentially important outcomes.

Statistical

properties: these can be mathematically expressed, for example, in

information theory terms, and include properties such as novelty, complexity,

violation of expectations (surprisingness), and incongruity.

All three categories of properties or attributes can independently and jointly

affect the listeners’ physiological arousal (especially the sympathetic part of the

autonomous nervous system). Furthermore, one can meaningfully speak of the

hedonic

appeal

,

pleasure

, that one receives from fluctuations of arousal (within

certain boundaries).

Most pertinently, one can with good reason think of the various decisions that

a composer makes as

musical

artistic

devices

that are related to the three catego-

ries of variables outlined above. Many of the decisions involve a very high degree

of musical knowledge, including form, instrumentation, orchestration, and a

thorough familiarity with the past and contemporary works. Intuition and sub-

conscious manipulation of musical ideas almost certainly play a part, and so

does “inspiration” that often implies striving for innovation, for pushing or

breaking the boundaries of, for example, a musical form.

Compositional decisions undoubtedly affect arousal-level fluctuations, pro-

ducing what Berlyne (1971) has called arousal boosts, drops, jags, and boost-jags.

This can happen in both small-scale and large-scale musical structures—involving

the type of instrumentation, thematic development, relations between sections of

a musical piece, dynamics, tonal closure, and dissonances (Konečni, 1986a,

1986b). Some of these ideas are perhaps more appropriate for the description of

the goals and devices of composers before the 20th C., but many remain valid in

contemporary compositions, such as those that deal with devices the characteris-

tics of which fall on the psychophysical (timbre more than dynamics) and statis-

tical (surprisingness, aleatorics, unpredictability) dimensions—referentiality

perhaps less so.

Let us first briefly, without detail and complications, examine a simple exam-

ple—the likely arousal-level fluctuations of listeners exposed to a classical musi-

cal form, the

sonata

(also sometimes called the

sonata-allegro

form). The stan-

dard sections are: fast movement, such as

allegro

(engaging the audience, raising

arousal); slow movement, such as

adagio

(reducing arousal, for example, for the

purpose of calm contemplation); a

scherzo

or dance, such as

minuet

(moderately

raising arousal for entertainment); and ending with another fast movement,

such as

presto

or

vivace

(presumably leaving listeners in an “up”, “happy”

mood).

Turning now to the more complicated context of the Roman Catholic

Mass

:

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 122 Art and Design Review

The Church—both intuitively and from many centuries of experience—understands

the significance of arousal-level fluctuations, possibly even better than do com-

posers. Furthermore, the Church is aware of the positive relationship between

the hedonic appeal of music and listeners’ receptivity and openness to the reli-

gious message. Therefore, precisely the order, sequence, in which the

text

of the

Mass

has been laid out over time already takes such factors into account and fa-

cilitates the task of composers’ setting the text to music.

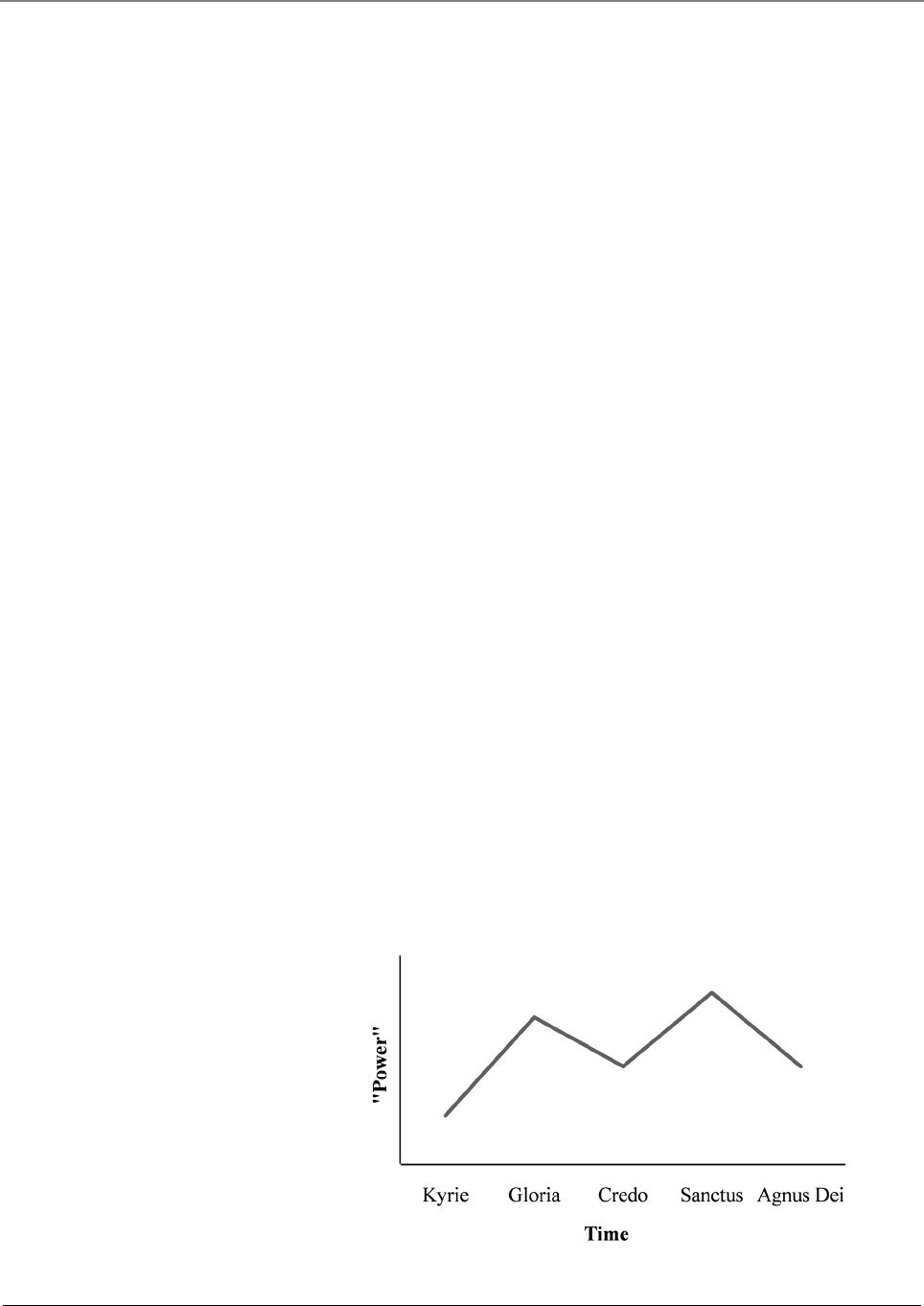

Here I offer a representation of the relationship between the traditional com-

ponents of the

Mass

—specifically in reference to the great

Mass

in

B

minor

,

BWV 232, of Johann Sebastian Bach—and listeners’ hypothetically experienced

“power” of the music, where “power” summarizes the effect of arousal-raising

and arousal-moderating devices that have been outlined above with regard to the

three categories of psycho-aesthetic variables (

Figure 1).

Briefly, the arousal-potential (“Power”) peaks of the

Mass

are

Gloria

and es-

pecially

Sanctus

(acclamations: “Holy, Holy, Holy”). The physiological thrills or

chills associated with these peaks have been discussed elsewhere (Konečni, 2005,

2011; Konečni, Wanic, & Brown, 2007). The comparative “valleys” (especially

Credo

and

Agnus

Dei

) are unlikely to imply listeners’ detachment, but rather

deep contemplation and “being moved” or “touched” in the language of the

Aesthetic

Trinity

Theory

of Konečni (2005, 2011).

7. “Power” of Music and Church Doctrine East and West

Before discussing this issue explicitly in music, it is useful to consider first a

comparable issue in the visual arts. Presumably because of the prohibition of

images in the Old Testament, there was hostility to their use in early Christiani-

ty, but this position was later gradually relaxed. Until, that is, in the 8th C., the

powerful

iconoclastic

movement reaffirmed the belief in the absolute transcen-

dence and invisibility of God and insisted on the total abolition of pictorial re-

presentation. However, there was much popular support for the veneration (not

worship) of images, led by monastic communities. After much struggle, some-

times unseemly, the view advanced especially by St. John of Damascus (John

Figure 1.

Arousal

Potential

(“Power”) over time.

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 123 Art and Design Review

Damascene, the “golden speaker”) prevailed: “God, though invisible by nature,

can and must be represented in His human nature, as Jesus Christ” (Meyendorff,

1926: p. 23).

Consider, then, the momentous importance for all humanity, the visual arts

both East and West, of this decisive defeat of iconoclasm at the Second Council

of Nicaea in 787 AD (this was the last of seven ecumenical councils of the East-

ern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church). Thus, one now has the

great Western religious paintings and the magnificent Eastern frescoes and

icons.

The somewhat analogous, but even more consequential, issue in music has to

do with the use of instrumentation in Church service. In this regard, East and

West diverged early and to this day the Eastern Orthodox Church believes that

the voice of God is best and sufficiently expressed without any adornment,

through the human voice alone. In contrast, the Western Church moved from

the pure Gregorian plainchant first to polyphony and then to instrumental ac-

companiment. Because of such developments, Orthodox composers have had

very limited choices in liturgical creativity. It is clear that the possibility of in-

strumentation not only hugely increased the range of compositional choices of

Western (Roman Catholic and Protestant) composers, but also the number and

type of arousal-raising and arousal-moderating devices at their disposal. West-

ern religious music could thus become more multi-faceted and more “beauti-

ful”—although some would say “prettier”, at the cost of losing ancient purity

and depth.

Orthodox Churches of, for example, Bulgaria, Russia, and Serbia are heirs in

the Slavic world of Byzantium, for by the 6th C., the ancient Christian Churches

in Alexandria (Coptic) and Antioch (now Syria) had broken off with Constanti-

nopolis (the “Second Rome”) over various schisms. Incidentally, it is worth re-

membering that from the 6th to the 11th C. Constantinopolis was the richest

and most powerful city in Christendom. Many complicated, painful, and indeed

sordid events (such as the sacking of Constantinopolis in 1204, in the Fourth

Crusade, by the Western “Latins”) ensued over the centuries.

To make a long story short, from the standpoint of musical aesthetics, in Rus-

sia and Serbia there is

Liturgy

(the equivalent of the Roman Catholic Mass),

which is a Eucharistic service of the Eastern Orthodox Church. There are several

versions, the most celebrated being the

Divine

Liturgy

of St. John Chrysostom

(347-407 AD), Archbishop of Constantinopolis, “the golden-mouthed”, re-

nowned for his intelligence and eloquence. In this

Liturgy

, musical instruments

are never used and for a long time there were male voices only. A number of

Orthodox composers have tackled it, notably Pyotr Ilych Tchaikovsky and Sergei

Rachmaninoff.

Tchaikovsky’s Op. 41 (1878) is a deeply felt, obviously

a

cappella

, composition

that consists of settings of texts from St. John’s

Divine

Liturgy

. In an 1878 letter

to Nadezhda F. von Meck, Tchaikovsky wrote: “The Church possesses much

poetic charm. I very often attend services and consider the liturgy of St. John

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 124 Art and Design Review

Chrysostom one of the greatest productions of art. If we follow the service very

carefully, and enter into the meaning of every ceremony, it is impossible not to

be profoundly moved by the liturgy of our Orthodox Church” (Modest

I.

Tchaikovsky, 1904: pp. 237-238).

Rachmaninoff’s Op. 31 (1910) is an Eastern Orthodox

Liturgy

that consists of

twenty sections for unaccompanied mixed choir. The 2nd (“Bless the Lord, О

My Soul”), 10th (

Nicene

Creed

), and 12th (“We Praise Thee”) sections contain

solo passages for alto, basso, and soprano, respectively. Rachmaninoff wrote the

following to Nikita Morozov: “I have been thinking about the Liturgy for a long

time and strove to write it. I suddenly became fascinated with it and then fi-

nished it very quickly. Not for a long time have I written anything with such

pleasure” (Moody, 1994).

Additional comments should be accorded at this point to the previously men-

tioned Vyacheslav Artyomov and his (Latin)

Requiem

.

2

Artyomov stands alone

as the only Russian, or indeed as the only Orthodox, composer to have been

drawn to the

Missa

pro

defunctis

, the pinnacle of Roman Catholic musical

structures. Especially given his profound Russianness and his sincere Orthodox

Christianity, surely such a choice of musical form is musically, socially, and

psychologically of interest. At least three facts should be noted. First, Artyomov’s

music suffered an official boycott for some twenty years prior to 1985. Second,

the dedication of his

Requiem

is: “To the Martyrs of the Long-Suffering Russia”.

Third, this composition was certainly not meant for church performance:

78-minute duration, six soloists, two choirs (one children’s), a symphony or-

chestra, some 250 performers in all. And while the entire detailed structure of

the Requiem Mass is present, this is, in a sense, a musical representation of a

ge-

neralized

idea

of

the

Requiem

: of agony, death, and, hopefully, redemption

.

Perhaps precisely in order to be able to deal with martyrdom on a gigantic

scale and the breadth of emotions and musical ideas it inspired in him, Artyo-

mov may have opted for the ancient and firm, yet “alien”, structure of the Latin

Requiem

Mass

as a vehicle that would harness and discipline his ideas and mus-

ical forces. In this light, it is also perhaps not surprising that Artyomov gave

such, previously mentioned, prominence to the setting of

Dies

irae.

This power-

ful, archaic text, with both the divine and human emotions of anger, grief, and

forgiveness, and the philosophical implications of terrible sin and infinite grace,

rises to the demands of the occasion. In Artyomov’s

Requiem

, ancient sensibili-

ties and mysticism of Orthodox Christianity and the unspoken sounds of me-

diaeval Church Slavonic gently emerge between the lines of the formidable Latin

text, mellowing it.

8. Final Thoughts

At the time (1988) when Artyomov completed his

Requiem

, one ventured to

think that on the threshold of the new millennium a sublime fusion could occur

2

A small part of this article draws on unpublished symposium lecture and concert program notes by

V. J. Konečni (1997a, 1997b) regarding Vyacheslav Artyomov’s

Requiem

(1985-1988).

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 125 Art and Design Review

between the sentiments of the Old and New Testaments, between East and West,

Orthodoxy and Catholicism—among Rome, Constantinopolis, and the Third

Rome, Moscow. As of this writing, in late April of 2020, this hope has sadly not

materialized.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this pa-

per.

References

Abra, J. (1995). Do the Muses Dwell in Elysium? Death as a Motive for Creativity.

Crea-

tivity

Research Journal, 8,

205-217. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj0803_1

Berlyne, D. E. (1971).

Aesthetics

and

Psychobiology

. New York: Appleton-Century-Croft.

Berlyne, D. E. (1974).

Studies

in

the

New

Experimental

Aesthetics:

Steps

toward

an

Ob-

jective

Psychology

of

Aesthetic

Appreciation

. Washington DC: Hemisphere Publishing

Corporation.

Cormican, B. (1991).

Mozart’s Death—Mozart’s Requiem.

Belfast: The Amadeus Press.

Deane, B. (1979). [Liner notes].

Cherubini

Requiem

in

D

Minor

(Recorded by the Orche-

stre de la Suisse Romande, Conducted by Horst Stein, and Chorale du Brassus, Chorus

Master André Charlet; LP). London: Decca.

Deane, B. (1981). [Liner notes].

Cherubini

Requiem

in

C

Minor

(Recorded by Philhar-

monia Orchestra, Conducted by Riccardo Mutti, and Ambrosia Singers, Chorus Master

John McCarthy; LP). London: Angel Records Digital.

DeVenny, D. P. (1990).

American

Masses

and

Requiems:

A

Descriptive

Guide.

Berkeley,

CA: Fallen Leaf Press.

Julian, J. (1892).

Dictionary

of

Hymnology.

New York: C. Scribner’s Sons.

Kivy, P. (1990).

Music

Alone.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Konečni, V. J. (1979). Determinants of Aesthetic Preference and Effects of Exposure to

Aesthetic Stimuli: Social, Emotional, and Cognitive Factors. In B. A. Maher (Ed.),

Progress

in

Experimental

Personality

Research

(Vol. 9, pp. 149-197). New York: Aca-

demic Press.

Konečni, V. J. (1982). Social Interaction and Musical Preference. In D. Deutsch (Ed.),

The

Psychology

of

Music

(pp. 497

-

516)

.

New York: Academic Press.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-213562-0.50021-8

Konečni, V. J. (1986a). Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion”: A Rudimentary Psychological

Analysis, Part I.

Bach, 17(3),

10-21.

Konečni, V. J. (1986b). Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion”: A Rudimentary Psychological

Analysis, Part II.

Bach, 17(4),

3-16.

Konečni, V. J. (1997a).

On Music and Death—With Special Reference to Vyacheslav Ar-

tyomov’s Requiem.

Unpublished Notes for a Lecture Given on February 26, 1997, at a

Festival Devoted to the Music of V. Artyomov at Bethaniënklooster, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands.

Konečni, V. J. (1997b, October-November).

Vyacheslav Artyomov’s Requiem: A Human-

ist Document? [Rekviem Vyacheslava Artyomova: Proizvedenie Gumanista?] Concert

Program Note (in Russian, English, and French, pp. 11-16) for Performances of the

Requiem at Moscow Conservatory Great Hall, Conductor D. Kytaenko

. Moscow: Fond

V. J. Konečni

DOI:

10.4236/adr.2020.82008 126 Art and Design Review

Duchovnogo Tvorchestva.

Konečni, V. J. (2005). The Aesthetic Trinity: Awe, Being Moved, Thrills.

Bulletin

of

Psy-

chology and the Arts, 5,

27-44. https://doi.org/10.1037/e674862010-005

Konečni, V. J. (2008). Does Music Induce Emotion? A Theoretical and Methodological

Analysis.

Psychology

of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 2,

115-129.

https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3896.2.2.115

Konečni, V. J. (2011). Aesthetic Trinity Theory and the Sublime.

Philosophy

Today, 55,

64-73. https://doi.org/10.5840/philtoday201155162

Konečni, V. J. (2013). Music, Affect, Method, Data: Reflections on the Carroll v. Kivy

Debate.

American

Journal of Psychology, 126,

179-195

.

https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.126.2.0179

Konečni, V. J. (2015). Emotion in Painting and Art Installations.

American

Journal

of

Psychology, 128,

305-322. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.128.3.0305

Konečni, V. J., Wanic, R. A., & Brown, A. (2007). Emotional and Aesthetic Antecedents

and Consequences of Music-Induced Thrills.

American

Journal

of Psychology, 120,

619-643. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20445428

https://doi.org/10.2307/20445428

Merrick, P. (1987).

Revolution

and

Religion

in

the

Music

of

Liszt.

New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Meyendorff, J. (1926).

The

Byzantine

Legacy

in

the

Orthodox

Church.

Crestwood, NY: St.

Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Moody, I. (1994). [Liner notes].

Rachmaninov:

The

Divine

Liturgy

of

St.

John

Chrysos-

tom,

Op.

31

. (Recorded by Gorydon Singers, Deacon Peter Scorer, and Conducted by

Matthew Best; CD). London: Hyperion Records.

Robertson, A. (1968).

Requiem:

Music

of

Mourning

and

Consolation.

New York: F. A.

Praeger.

Tchaikovsky, M. (1904).

The Life and Letters of Peter Illich Tchaikovsky

. London: John

Lane Company.

Wolff, C. (1994).

Mozart

’

s

Requiem:

Historical

and

Analytical

Studies,

Documents,

Score

(Whittall, M., Trans.)

.

Berkeley/Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

(Original Work Published 1991)