Institut

C.D.

HOWE

Institute

commentary

NO. 522

Piling On – How

Provincial Ta xation

of Insurance Premiums

Costs Consumers

Most consumers don’t know that provinces levy a tax on their insurance premiums – making

insurance more expensive and lowering demand. This insurance premium tax, once meant

as an alternative to the corporate income tax for insurers, has long been obsolete.

The provinces should rethink their approach to insurance taxation to

make it more equitable and less costly for consumers.

Alexandre Laurin and Farah Omran

E

s

s

e

n

t

i

a

l

P

o

l

i

c

y

I

n

t

e

l

l

i

g

e

n

c

e

|

C

o

n

s

e

i

l

s

i

n

d

i

s

p

e

n

s

a

b

l

e

s

s

u

r

l

e

s

p

o

l

i

t

i

q

u

e

s

I

N

S

T

I

T

U

T

C

.

D

.

H

O

W

E

I

N

S

T

I

T

U

T

E

Daniel Schwanen

Vice President, Research

C N. 522

October 2018

F T P

e C.D. Howe Institute’s reputation for quality, integrity and

nonpartisanship is its chief asset.

Its books, Commentaries and E-Briefs undergo a rigorous two-stage

review by internal sta, and by outside academics and independent

experts. e Institute publishes only studies that meet its standards for

analytical soundness, factual accuracy and policy relevance. It subjects its

review and publication process to an annual audit by external experts.

As a registered Canadian charity, the C.D. Howe Institute accepts

donations to further its mission from individuals, private and public

organizations, and charitable foundations. It accepts no donation

that stipulates a predetermined result or otherwise inhibits the

independence of its sta and authors. e Institute requires that its

authors publicly disclose any actual or potential conicts of interest

of which they are aware. Institute sta members are subject to a strict

conict of interest policy.

C.D. Howe Institute sta and authors provide policy research and

commentary on a non-exclusive basis. No Institute publication or

statement will endorse any political party, elected ocial or candidate

for elected oce. e views expressed are those of the author(s). e

Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

The C.D. Howe Institute’s Commitment

to Quality, Independence and

Nonpartisanship

About The

Authors

A L

is Director of Research

at the C.D. Howe Institute.

F O

is a Junior Policy Analyst

at the C.D. Howe Institute.

$12.00

978-1-987983-77-7

0824-8001 (print);

1703-0765 (online)

Insurance premiums have been taxed by Canadian governments for so long – some provinces and

municipalities collected small levies as early as the late 1800s – that they’ve become a xture rarely

discussed in the literature and the nancial press. For many years, insurance premium taxes were collected

from insurers as an alternative to taxing their prots. But this practice is now long gone since all Canadian

governments tax the corporate income of insurance companies, in addition to premium taxes and other

taxes and levies.

Most insurance consumers do not know that a provincial insurance premium tax (IPT) ranging from

2 percent to 5 percent is levied on their premiums. In addition, ve provinces charge a retail sales tax

(RST) ranging from 6 to 15 percent on top of the premium taxes for certain types of insurance. In Quebec

and Ontario, the RST rates of respectively 9 and 8 percent generally apply to group life and health

insurance, and property and casualty insurance (although Ontario excludes auto insurance). Saskatchewan

is the latest province to introduce an RST. Since insurance is a nancial service, premiums are exempt from

GST/HST.

So why do provinces still tax insurance premiums? While IPTs and RSTs on premiums are largely

invisible to customers on whom the burden ultimately falls, they generate more than $7 billion of stable

and growing provincial government revenues – representing about 7 percent of all provincial taxes

collected on goods and services.

Premium-based taxes increase the price of insurance products and lower the demand for them. We nd

that an increase of one percentage point in the provincial IPT rate leads to a 10 percent decrease in the

number of life insurance contracts sold. Reduced insurance coverage for natural disasters such as oods

and earthquakes, other catastrophes, relief to a deceased's family, or relief of the nancial burden of illness

and disability may lead to increased cost pressures on government budgets down the road.

Canadian governments should revisit and reassess the taxes imposed on insurance products. At a

minimum, IPT liabilities should be made creditable against corporate income tax liabilities, partly

restoring their original role as a substitute for taxing prots. And provinces that impose an RST on IPT-

inclusive premiums should lead the way and eliminate this form of double taxation. A more ambitious

reform would remodel the patchwork of transaction taxes for insurance services to a comprehensive and

broad-based, value-added system, bringing down the insurance industry's high transaction tax burden and

ensuring greater comparability with other industries.

The Study In Brief

C.D. Howe Institute Commentary© is a periodic analysis of, and commentary on, current public policy issues. Michael Benedict

and James Fleming edited the manuscript; Yang Zhao prepared it for publication. As with all Institute publications, the views

expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reect the opinions of the Institute’s members or Board of

Directors. Quotation with appropriate credit is permissible.

To order this publication please contact: the C.D. Howe Institute, 67 Yonge St., Suite 300, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1J8. e full

text of this publication is also available on the Institute’s website at www.cdhowe.org.

2

Now, provinces collect about $7.3 billion in excise

and retail sale taxes on these premiums, in addition

to $4.4 billion in corporate income and other taxes

on insurers. Even with such a long history and high

tax yield, there has been little study on the taxation

of insurance premiums. In general, tax policy

analysts have not paid much attention.

Bringing new policy attention to this important

but ignored topic is the primary motivation for this

Commentary. As we demonstrate, the insurance

premium taxes combined with multiple sales taxes

paid or remitted by insurers increase the cost of

insurance for consumers but bring in considerable

revenues for provincial governments in particular.

Hidden in the premiums paid, these tax costs

reduce the demand for insurance.

For many individuals and businesses, insurance

provides nancial protection against uncertain

events and, as such, can be likened to a form of

precautionary savings. Insurance creates value

by pooling similar individual and business risk

exposures. It is a nancial intermediation product

to the extent that premiums create a nancial claim

on the insurance pool, with regulated insurance

companies managing the pool and acting as the

intermediary with policyholders while assuming the

residual risk.

Although the federal government does not tax

insurance premiums, provincial governments do.

Most insurance consumers do not know that a

provincial insurance premium tax (IPT) ranging

from 2 percent to 5 percent is levied on their

premiums. In addition, ve provinces (including

Ontario and Quebec) charge a retail sales tax on top

of the premium taxes for certain types of insurance.

In this Commentary, we rst provide a broad

lay of the land for insurance premium taxation

– its origins, its role as consumption and wealth

accumulation taxes, and as a revenue source for

governments. Next, we explore policy issues,

including a discussion of how the tax system for

insurance has evolved beyond its original policy

motivations, how multiple transaction taxes lead to

high and arbitrary eective tax rates on insurance

consumption, the impact of potential wealth

taxation on tax fairness and how premium taxes can

lead to fewer people purchasing insurance coverage

with the potential to increase cost pressures on

government budgets.

Finally, we discuss policy options, including

the elimination of provincial IPTs and/or the

elimination of retail sales taxes on tax-inclusive

premiums. Because the provincial scal losses would

be large, we propose a reshaping of the transaction

tax system that would make insurance services

subject to value-added taxation.

Taxes on insurance premiums have been a xture of the Canadian

tax system since the early 1900s when insurance companies were

subject to very little other tax.

e authors would like to thank Dalton J. Albrecht and Stephen J. Rukavina whose work was inuential background

research and inspired the analysis in this study. e authors thank Pascal Dessureault, Nadja Dre, Kenneth James

McKenzie, Noeline Simon, Kevin Wark, members of the Fiscal and Tax Competitiveness Council of the C.D. Howe

Institute and anonymous reviewers for comments on an earlier draft. e authors retain responsibility for any errors and the

views expressed.

3

Commentary 522

Taxes on Insurance Premiums–

Lay of the Land

e purpose of insurance is nancial protection for

a loss and/or cost. Even without insurance products

per se, individuals can insure themselves from

unexpected occurrences through personal savings.

For example, a person may want to save to cover

liabilities and expenses that are anticipated to arise

upon his/her death. Assuming they have disposable

income, people can always self-insure, and every

instance of self-insurance involves the accumulation

of savings. At its roots, insuring against potential

and real outcomes is a form of precautionary savings.

Self-insurance, however, can be very inecient

for those who over save and those who under

save. By acting as the intermediary for individuals

exposed to a similar risk, an insurer pools individual

risks and reduces individual costs (the premiums)

of insuring against an uncertain outcome. Insurance

products create cost certainty for the insured

persons: they determine how much they need to

cover a risk, an amount that is often much lower

than self-protection (precautionary savings) would

require. Moreover, insurance allows for the transfer

of risk from risk-averse consumers to insurance

companies.

No GST/HST is charged on the sale of

insurance policies. Indeed, most nancial services

are exempt from GST/HST since it is often

dicult to distinguish the value-added provided

by the nancial intermediation activity (which

we would like to tax) from simple nancial ows

and compensation for underwriting risk (Firth

1 When a Canadian resident purchases insurance from an unlicensed insurer or an unlicensed intermediary (broker), which

is typically a foreign insurance provider, the tax treatment diers. Under the Excise Tax Act, net premiums of such insurance

products are subject to a 10 percent federal excise tax (FET). However, the FET does not apply to reinsurance, life, personal

accident, sickness and marine-risk insurance (Canada Revenue Agency 2014). In addition, the resident is required to self-

assess and pay the provincial insurance premium tax (Albrecht and Rukavina 2016). It will also be necessary for the broker

– or if unavailable, the resident – to collect and remit any applicable sales tax. Some provinces have specied dierent

premium tax rates for these cases. For example, BC imposes a 7 percent tax on the insured if insurance is purchased from an

unlicenced insurer.

and McKenzie 2012). Being exempt, the insurer is

unable to claim input tax credits for the GST/HST

it incurs on operational expenses and claims, and

eectively stands in the shoes of the end consumers,

paying those taxes on their behalf and embedding

their cost in the premiums themselves.

However, all provinces and territories impose

IPTs, varying in amount by province and by

insurance product. In addition, ve provinces

levy retail sales taxes (RST) on some insurance

premiums: Ontario, Manitoba, Quebec and, most

recently, Saskatchewan along with Newfoundland

and Labrador (Table 1).

In this Commentary, we focus on provincial

premium taxes on insurance policies sold by

domestic licensed insurers to Canadian residents.

1

Recently, these tax rates have been rising.

Life Insurance

ree-quarters of all life insurance policies in force

provide coverage up to an agreed upon date. Labelled

“term insurance,” these products are primarily

intended to protect families against the risk of one

member dying prematurely and leaving debts and

an income to replace. About one-half of all term

insurance products are purchased by individuals,

with the rest bought on a group basis (and priced

according to the characteristics of the group as a

whole) through an association or an employer.

e remaining one-quarter of all life insurance

policies are permanent and purchased on an

individual or corporate basis. Premiums may

be paid over a set number of years or for life. It

4

provides protection for premature death while

allowing reserves to accumulate within the policy.

As the permanent life insurance contract ages,

these reserves can be used to fund future premiums,

and extracted to supplement retirement income or

fund emergencies. Many permanent life insurance

contracts, therefore, resemble savings products in

which the insurer guarantees a death benet to a

survivor, but in which an accessible cash value grows

as a result of the returns on invested premiums

(which may be guaranteed as well).

e Income Tax Act (ITA) regulates the taxation

of the investment income earned on the savings in

a life insurance policy as well as on gains from the

disposition of an interest in a policy. An exemption

test is applied to determine whether a life insurance

policy is more protection oriented or savings

oriented and, in turn, if it is an exempt or non-

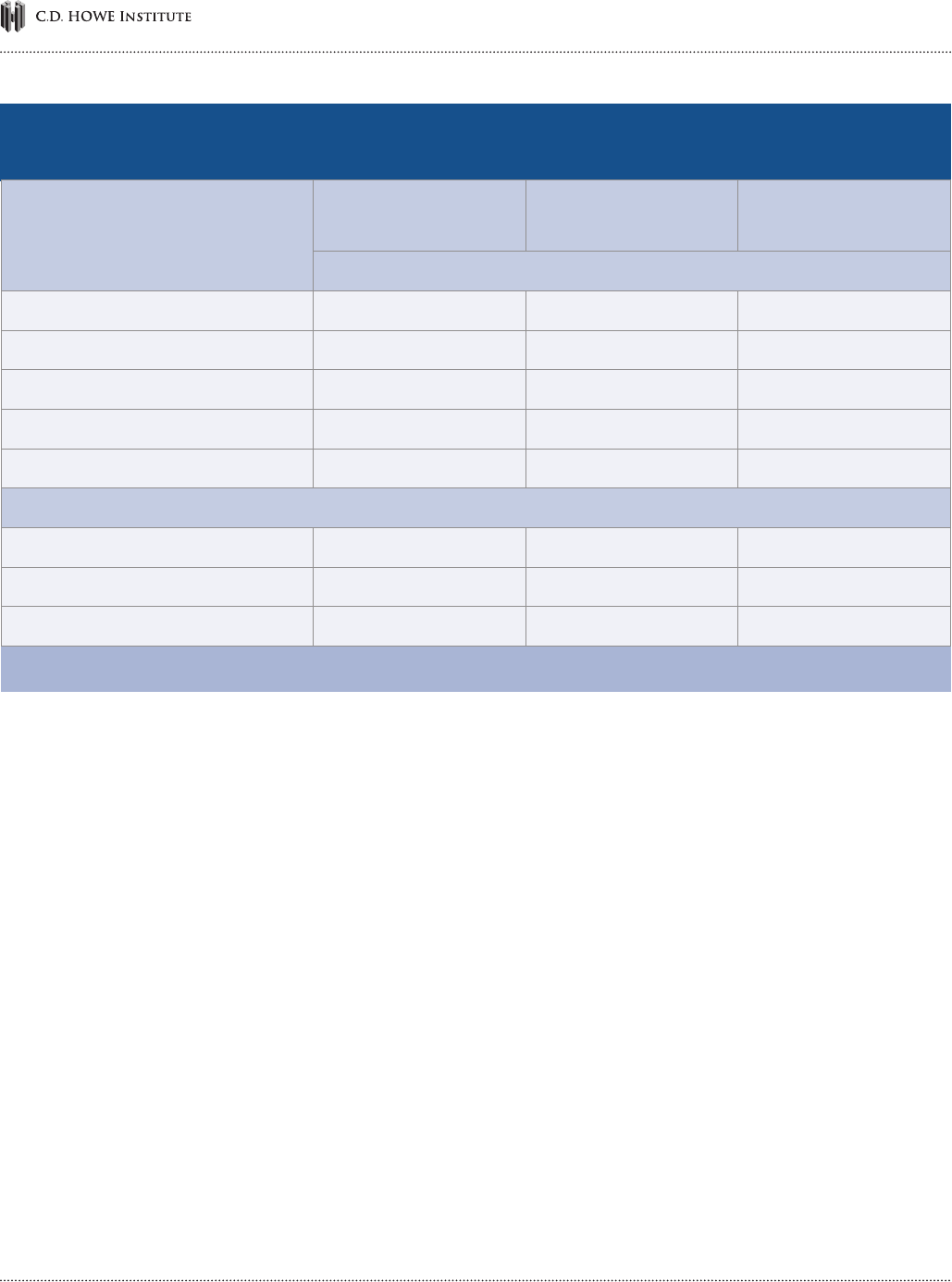

Table 1: Provincial Insurance Premium Tax Rates (to licensed insurers) and Retail Sales Tax Rates, 2017

Notes: (1) On P&C only. (2) Group life and health, and P&C. (3) Group life and health, and P&C. Auto insurance exempt. (4) Group life

and P&C. (5) P&C.

*Quebec has an additional 0.48% compensation tax, which was originally planned to decrease to 0.3% after March 31, 2017 and to be phased

out after March 31, 2019, but which has been extended until 2020. Ontario and BC IPT rates on P&C vary. ey are 3.5% (ON) and 4.4%

(BC) on property, and 3% (ON) and 4% (BC) on all other P&C products.

Sources: Albrecht and Rukavina (2016), PWC (2017), and authors' compilation from publicly available sources.

Province

Life, Accident and

Sickness

Property and

Casualty

Additional Fire

Premium Tax

Retail Sales Tax

(percent)

Newfoundland and Labrador 5.00 5.00

15.00

(1)

Prince Edward Island 3.50 3.50 1.00

Nova Scotia 3.00 4.00 1.25

New Brunswick 2.00 3.00 1.00

Quebec* 3.48 3.48

9.00

(2)

Ontario* 2.00 3.50

8.00

(3)

Manitoba 2.00 3.00 1.25

8.00

(4)

Saskatchewan 3.00 4.00 1.00

6.00

(5)

Alberta 3.00 4.00

British Columbia* 2.00 4.40

Yukon 2.00 2.00 1.00

Northwest Territories 3.00 3.00 1.00

Nunavut 3.00 3.00 1.00

5

Commentary 522

exempt policy.

2

If the policy qualies as exempt, the

investment income is not subject to accrual taxation

for the policyholder, unless it is withdrawn rather

than paid out due to death or disability. Instead, the

ITA imposes a 15 percent investment income tax,

payable by the insurers on deemed net-investment

income earned within the policy.

So if the policy is non-exempt, annual policy

gains are taxed on an accrual basis in a similar

manner to interest income.

3

And if there is a

disposition of an exempt policy prior to the death

of the insured, any policy gain (dened as the

dierence between the proceeds of the disposition

and the adjusted cost basis of the policy) is subject

to tax.

4

ere are currently some 90 active life insurers

and annuity providers in the Canadian marketplace.

In 2016, they paid $12 billion in life insurance

benets to Canadians. In the same year, they

accrued $8.3 billion for estimated future claims and

received $20.3 billion in life insurance premiums on

in-force and new policies. More than three-quarters

(79 percent) of premiums were generated from

individual policies, while the remaining 21 percent

came from group policies.

Overall, some 22 million Canadians own

about $4.5 trillion in life-insurance coverage, with

an average protection of $404,000 per insured

household. Individual insurance forms the majority

of life-insurance coverage, with individual term

life insurance accounting for more than half such

insurance (CLHIA 2017).

IPT rates on life insurance range from 2percent

to 5 percent (Table 1). Ontario, Manitoba and

Quebec apply RSTs of 8 percent, 8 percent and

2 Currently, nearly all life insurance policies available in Canada are exempt (Wark and O’Connor 2016).

3 See https://www.n.gc.ca/drleg-apl/lip-pav-n-eng.pdf.

4 See https://www.n.gc.ca/drleg-apl/lip-pav-n-eng.pdf.

5 is change came after Saskatchewan Party leader Scott Moe, who had made restoring the exemption part of his campaign,

became the province’s premier on Feb. 2, 2018. Quebec implemented a 9 percent sales tax on all individual life and health

insurance in 1985 but narrowed its scope the following year to only group life and health coverage.

9 percent, respectively, on group life insurance

premiums. Saskatchewan briey charged RST on

both individual and group life insurance, eective

on Aug. 1, 2017 – making it the only jurisdiction

to tax individual life insurance – but retroactively

repealed the tax a few months later.

5

Health Insurance

Health insurance is purchased to fund the cost of

medical expenses not covered by government plans

and/or to provide protection against income loss

due to disability, serious accidental injuries, long-

term care and critical illness. Health insurance

protects against unexpected expenses related to

health conditions. ese costs are for the most part

non-discretionary and can run very high.

ere are some 130 health insurance providers in

Canada, with 70 of them simultaneously providing

life insurance. In 2016, they provided more than

25 million Canadians with supplementary health

insurance, and about 86 percent of total health

insurance premiums collected were paid out as

benets. Since health insurance has a less signicant

long-term savings element than life insurance,

it shows a high annual turnover of premiums to

benets (CLHIA 2017).

About three-quarters of all health benets were

paid out as medical-expense reimbursements such

as prescription drugs, dental and hospital expenses;

about one-fth were for disability insurance

plans. Almost all (90 percent) health insurance is

sold on a group (employers, unions, professional

associations) basis.

6

e premium tax treatment of health insurance

is similar to that of life insurance. e same IPT

rates, which dier across provinces, are levied on

health insurance. Ontario and Quebec also levy

the same RST on group health insurance. For its

part, Manitoba exempts group healthcare plans

from the RST. BC is a special case, as it exempts

premiums paid for approved medical services or

healthcare plans.

Property and Casualty Insurance

Property and Casualty (P&C) insurers cover the

loss or damage to automobiles, homes, businesses

and other properties. In some instances, the

purchase of P&C insurance is mandated by lenders

or by government policy. Lenders, for example,

often require insurance on mortgaged properties or

car loans, while a minimum level of auto insurance

coverage is compulsory in all provinces.

In 2016, there were more than 200 P&C

insurance providers in Canada. Of the almost $50

billion paid in P&C premiums, almost half was for

vehicle insurance. In addition, BC, Saskatchewan,

Manitoba and Quebec operate their own public

insurance schemes covering the compulsory

component of auto insurance (IBC 2017).

In addition to IPT on P&C premiums,

Ontario, Manitoba, Quebec, Saskatchewan and

Newfoundland and Labrador impose RST on

the sale of those insurance contracts, with auto

insurance exempt in Ontario (Table 1). Some

provinces, including Manitoba, New Brunswick,

Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and

Saskatchewan, levy additional or higher premium

taxes on re insurance and/or certain property

insurance.

6 See Metropolitan Life Ins. Co. v. Ward, 470 U.S. 869, 105 S.Ct. 1676, 84 L.Ed.2d 751 (1985).

International Experience

Canada is not the only country that charges

transaction taxes on insurance premiums. Indirect

taxes on insurance premiums, or stamp duties, are

common in most jurisdictions around the world.

In the US, every state levies an insurance

premium tax on insurers. e tax rates dier by

state, but also between domestic or out-of-state

insurers. Some states also levy a retaliatory tax,

which is the percentage dierence between the tax

rate of the domicile state and the foreign tax rate

of the jurisdiction in which the premium is written.

is means that the insurer pays the higher of the

two rates.

6

In several states, state corporate income tax

liabilities may be credited against insurance

premium taxes, but more frequently (in 40 states)

the premium tax is in lieu of the corporation

income tax. For instance, in California all insurers

pay a premium tax in lieu of all other taxes. In

Florida, insurers are subject to both premium and

corporate income taxes, but income taxes may

be credited against premium taxes. Furthermore,

to encourage jobs to locate in the state, Florida

provides for a salary credit against the insurance

premium tax.

In Europe, taxation of insurance premiums and

contracts is common and takes various forms. Table

A1 in Appendix A summarizes this tax treatment

in 27 European countries that have some form

of indirect taxation on insurance contracts. Most

countries exempt life insurance, and a few others

exempt health insurance as well. In almost all

cases, the insurer is liable to pay the tax if they are

licensed to operate in the jurisdiction; otherwise the

tax still applies and the policyholder is responsible.

Some European countries are required by law, or

7

Commentary 522

it is common practice, to inform the policyholder

of the tax separately from the premium. Over

the past two years, some countries, including

Colombia, Malta, Portugal, Slovenia, Italy and

the UK, increased their insurance premium taxes

on insurance products (EY 2015, 2016). Estonia,

Latvia, Norway and Turkey are the only European

countries included in Appendix A that have no

indirect taxation on insurance contracts (Insurance

Europe 2017).

Why Tax Insurance Premiums?

Little literature exists specically on the rationale

for provincial taxation of insurance premiums.

Originally, IPTs were seen as an alternative to taxing

the earnings of insurers. ey can also be seen as

an attempt to tax consumption, or as an indirect

attempt to tax increases of net worth. But the most

compelling reason seems to be simply that these

provincial taxes provide signicant revenues while

being largely invisible to consumers and savers.

Origins: In Lieu of Taxing Insurers’ Earnings

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, some provinces

and municipalities collected small levies on items

such as corporate capital, railway track mileage,

bank reserves and insurance premiums (Whaley

1970). For its part, the federal government rst

enacted an insurance premium tax in the 1915

Special War Revenue Act (renamed the Excise Tax

Act in 1947) to help nance the First World War. A

number of commodity taxes were also introduced

in this act, including the general manufacturer’s

sales tax that was replaced by the GST in 1991. e

insurance premium tax applied only to non-life,

7 Only the income of non-life stock insurance companies, and the portion of net earnings of a stock life insurance company

allocated to the shareholders’ fund, whether distributed as share dividends or not, were subject to corporate income tax.

However, premium taxes were credited against insurers’ income tax liability, such that only income tax liability in excess of

premium taxes was payable.

non-marine insurance premiums at a rate of

1 percent. Given the introduction of this premium

tax at a time when P&C and health insurance were

in their edgling stages of development, it did not

raise signicant tax revenues in the early years.

When the federal government implemented

a corporate income tax in the 1917 Income War

Tax Act (renamed Income Tax Act in 1948), life

insurance companies and all mutual insurance

companies were mostly exempted.

7

In eect,

insurance premium taxes were collected as a

minimum tax, in lieu of the corporate income tax.

is practice continued for decades, even for a few

years after the federal government vacated this

eld in 1957 for provinces to resume their own

premium taxes (provinces had vacated the eld in

1941 for the rst wartime tax rental agreement; see

Provincial Budget Round-Up 1957).

Clearly, Canadian governments originally

regarded IPTs as an alternative means of taxing the

earnings of insurance activities. And, indeed, the

same logic still applies today in American states

where premium taxes are viewed as a substitute for

corporate income tax.

When provinces regained the corporate

taxation eld in 1962 following the end of a

series of federal-provincial tax rental agreements

(except Quebec, which had opted out in 1952,

and Ontario in 1957), they did not reactivate their

earlier suspended corporate income tax legislation

that contained either exemption for insurance

companies’ prots or else a credit against other

forms of provincial income tax. Instead, out of

administrative convenience, corporate provincial

taxable income was dened by direct reference to

the federal Income Tax Act – which at this time only

excluded prots of mutual life insurance companies.

8

ese prots became taxable for the rst time

in 1969.

Attempting to Tax Consumption

Another possible justication for taxing insurance

premiums would be to view IPTs as an attempt to

tax consumption. Even though the tax is paid by

the insurance provider, it is triggered by a purchase

and one might expect this cost to be passed on to

consumers – just as excise taxes on alcohol, tobacco

and fuel are, for the most part, ultimately borne

by the nal customers. Moreover, sales taxes on

premiums collected on certain types of insurance in

Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and in

Newfoundland and Labrador are straightforward

attempts to tax consumption.

Firth and McKenzie (2012) review the

literature around the taxation of nancial services

consumption in general and provide a theoretical

case for taxing the value-added component of the

nancial intermediation service when purchased by,

or on behalf of, individuals. Insurance companies

are regulated nancial intermediaries providing

value added by pooling risks in a cost-eective way.

In practice, it is dicult to accurately measure the

value added by nancial intermediation services,

especially for deposit taking institutions, which

explains why Canada and other countries exempt

most nancial services from their value-added

consumption taxes.

e value added by the insurance service is the

dierence between the premium revenue received

by the provider and the risk-adjusted present

value of the amount expected to be paid out to the

insured. Insurance services use up real resources

without a compensating increase in otherwise

taxable consumption. erefore, the portion of the

premiums used to pay for the service should be

8 As mentioned earlier, this is accomplished federally via the investment income tax for life insurance policies, even though

most such policies are exempt.

taxed under a broad-based, value-added tax. Under

this approach, a value-added consumption tax, such

as the GST/HST, should apply to the consumption

value of the nancial intermediation services, but

not to the entire premium as is currently the case

provincially (Barham et al. 1987).

Attempting to Tax Increases in Net Worth

Not only can all insurance be viewed as providing

consumption value, some types can also be viewed

as providing investment value. Insurance providers

must accumulate reserves to securely cover the

uncertain timing and extent of claims. e reserves

earn investment income on behalf of insurance

purchasers, indirectly, who are wealthier with the

insurance protection than without. Under the Haig-

Simons principle of individual income taxation, an

inuential tax policy benchmark in Canada and

around the world, all accretion to one’s economic

power should be taxed, regardless of its source.

Since taxing individuals on the implicit net-wealth

accretion within individual insurance policies is

largely impractical in most situations, premium

taxes may also be viewed as an indirect attempt

to tax this positive change in net worth at the

provincial level.

8

Generating Government Revenues

Tax systems in advanced economies seek to

achieve multiple objectives. One goal is to provide

distributional fairness, such that tax lers in

comparable situations pay relatively the same

taxes and those better able to aord it eectively

pay more. Another objective is to be neutral with

respect to economic decisions, such that the tax

system does not create unwanted distortions.

Although advanced tax systems are complicated,

9

Commentary 522

simplicity of administration and compliance

often gure in government goals. But of course

the most obvious purpose of the tax system is to

raise sucient and stable tax revenues that grow

with expenditure needs. On that score, insurance

premium taxes are a strong generator of stable

provincial government revenues.

IPTs are paid by the insurance providers and

are thus largely invisible to customers on whom

the burden ultimately falls. However, even though

it should make no dierence in theory whether

premium taxes are imposed on the insurance

suppliers rather than on the customers, the fact that

the tax is invisible to customers may inuence their

responses to it – people tend to be subjectively more

favourable to invisible (or less salient) taxes (Weber

and Schram 2013).

Plus, on the P&C side, demand for home and

vehicle insurance is relatively unresponsive to small

price changes since minimum coverage is mandated

by either government regulations or lenders.

Admittedly, relatively low price elasticity of demand

for certain products also means tax revenues

generated from their indirect taxation induces lower

economic distortions than would be generated

by corporate income taxes, for instance. All this

makes insurance premiums a prime target to raise

government revenues.

Indeed, in 2016 provincial governments raised

more than $3.2 billion in IPTs and some $4

billion in related sales taxes, for a total of $7.2

billion (Table 3). is is a substantial amount of

tax revenues, representing about 7 percent of all

provincial taxes collected on goods and services.

Canadian households indirectly support most

of this burden because taxes paid by insurers,

businesses and employers are ultimately passed on

through higher premiums, prices and lower benets.

However, this state of aairs raises fairness

issues. Households with children pay a highly

disproportionate share of IPTs and sales taxes on

premiums – in 2017, they represented one-quarter

of all households but directly or implicitly paid

about half of all premiums. Also, higher-income

households (which also tend to be families with

children) support a greater share of the premium

tax burden but to a much lesser degree than for

personal income tax (Table 2).

Policy Issues

Premium-based taxes, therefore, clearly raise a

number of policy issues. Conceived at a time when

income taxes and value-added taxes either did not

exist or were in early development, they might

be considered largely obsolete in a modern tax

system, particularly as insurance companies now

generally pay income tax. Second, in some cases

the same premiums or their proceeds are eectively

taxed multiple times in multiple transactions.

ird, they resemble a tax on the capital savings of

policyholders. And lastly, higher insurance prices

induced by taxes can lead to lower demand and less

take up of insurance.

An Obsolete Tax

As pointed out earlier, Canadian governments

originally regarded IPTs as an alternative to

taxing the earnings of insurance companies, or as

a minimum tax since premium tax liabilities were

creditable against other tax liabilities. As well,

premium taxes were regarded as easier to apply. is

same logic still prevails today in American states.

But now all Canadian governments tax the

corporate income of insurance companies, in

addition to premium taxes and other taxes and

levies. In fact, the insurance industry is now one

of the most heavily taxed industries in Canada

as a share of its value added. Indeed, life and

health insurers contributed $2.5 billion to federal,

provincial and local governments in 2016 through

10

taxes on their corporate income, capital, property,

investment income, operating expenses and payroll,

9

on top of $1.4 billion paid in IPTs and $2.3 billion

collected in provincial RSTs on certain premiums

(Table 3). In fact, governments collected as much

in corporate income and capital taxes ($1.4 billion)

from life and health insurers as they collected in

insurance premium taxes.

P&C insurers contributed even more to federal

and provincial tax coers, if we account for the sales

taxes they paid on insurance claims – $1.9 billion

in 2016 (Table 3). ey also paid $600 million in

corporate income taxes, plus $1.1 billion in taxes

on business realty, payroll and operating expenses,

as well as on provincial health levies. ey remitted

9 Excluding payroll taxes collected on behalf of employees.

$1.7 billion in provincial sales taxes collected

on premiums and paid $1.8 billion in insurance

premium taxes – much more than in corporate

income taxes (although the dierence between the

two was much less in 2015).

Canada’s tax regime has evolved considerably

since insurance premium taxes were rst introduced,

moving beyond its original purpose when

governments derived a substantial share of their

revenues from customs and excise taxes. Since

then, reliance on customs duties and excise taxes

has greatly diminished, the general manufacturer’s

sales tax has been eliminated and replaced with the

GST/HST, most capital taxes have been eliminated

or reduced, and governments rely considerably

Table 2: Percentage Distribution of IPTs and Sales Taxes on Premiums, Directly or Implicitly Paid, by

Income Quintiles and Household Types (2017)

Source: Authors’ simulations using Statistics Canada’s Social Policy Simulation Database and Model, version 26.

Household Income Quintile

Share of All

Households

Share of All Premium and

Sales Taxes

Share of All Personal

Income Taxes

(percent)

Q1 – Low 20 6 1

Q2 – Low-to-middle 20 11 4

Q3 – Middle 20 18 11

Q4 – Middle-to-high 20 27 21

Q5 – High 20 39 62

Household Type

With children 25 48 34

No children 45 34 49

Elderly no children 30 18 17

11

Commentary 522

more on income taxes and value-added taxes, which

better apply taxes to income. Premium taxes are

considered by some to be a “blunt instrument” and

may be viewed as obsolete in a modern tax system.

Multiple Transaction Taxes Compound the

Burden on Insurance Consumption

Providing insurance involves many sales transactions.

An insurance product is rst purchased by an

individual, a group of individuals or a business

through the payment of insurance premiums. ese

premiums are subject to taxes, which are hidden

in the prices purchasers pay. In some provinces,

the premiums are also subject to additional

sales taxes. en, insurance providers will incur

operating expenses in the pursuit of their nancial

intermediation activities, some of which will also

be subject to sales taxes. Finally, the insurers issue

claims payments on which they may also pay sales

taxes (e.g., automobile or residential repairs, or

physiotherapy treatments).

Since insurance premiums are GST/HST

exempt, insurance providers cannot claim the GST/

HST they paid on operational expenses as input tax

credits to reduce their tax liability. All GST/HST

and retail sales taxes paid on intermediate inputs are

passed on to consumers in higher premiums. GST/

HST and retail sales taxes paid on claims, as well as

IPTs, have the same eect: they inate premiums

charged. Similarly, retail sales taxes are charged on

the inated premium values, which are inclusive of

the other taxes – a tax on top of the other ones. is

cascading makes the total eective consumption tax

Table 3: Total Taxes Paid by Insurance Industry, $ Millions

Source: Canadian Health and Life Insurance Association (CHLIA) and Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC) industry publications.

Type

L&H Industry P&C Industry

2015 2016 2015 2016

($Millions)

Corporate income taxes 789 1,096 1,268 635

Insurance premium taxes 1,305 1,433 1,662 1,787

Provincial sales taxes on premiums 2,222 2,332 1,594 1,723

Sales taxes on claims - - 2,174 1,866

Sales taxes on operating expenses 276 302 458 385

Payroll taxes (employers’) 289 311 290 326

Health levies - - 323 341

Property and business taxes 414 412 34 30

Capital taxes 271 290 - -

Investment income taxes 131 121 - -

Total tax contribution 5,697 6,297 7,803 7,093

12

rate on premiums arbitrarily and confusingly higher

than the upfront tax rates.

A good basis for taxing the consumer value

of nancial intermediation can be found in the

literature on value-added taxation. In essence,

business value added is what is left once the cost

of all production capital inputs has been deducted

from the sales of goods and services. It would be

dicult in practice to identify and tax the value

added of an insurance service since value added

is conceptually the margin between premiums

received and risk-adjusted claims paid out – both

transactions may be spread out over a number of

years, and most claims are not subject to sales tax.

But the current system certainly does not limit itself

to produce a tax on the value added.

Two methods exist to tax business value added:

• the traditional invoice-based tax on sales, with

credits provided to businesses for tax paid on

inputs, like Canada’s GST/HST; and

• the addition-based method, which is a tax on the

sum of prots and wages, which also corresponds

to business value added.

e International Monetary Fund (IMF 2010)

recently suggested using the addition-based

method to implement value-added consumption

taxes on nancial services. Branded the Financial

Activities Tax (FAT), this addition-based VAT

was presented as a possible additional measure

beyond a new levy proposed to help meet the cost

of future nancial crises.

Figure 1: Transaction Taxes as a Percent of Value Added, 2012 to 2016

Source: Authors’ calculations. Value added is the sum of prots plus depreciation and total employee compensation. Value-added for the

Life, Health and P&C sectors is computed from Statistics Canada’s Financial and Taxation Statistics for Enterprises, along with data from the

CLHIA and IBC. Banking activity data are from annual nancial reports of Canada’s big banks (when available). Data on taxes paid come

from CLHIA (Life and Health), IBC (P&C) and Canadian Bankers Association (top six banks).

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

P&CLifeHealth Banking

Irrecoverable Sales Taxes on

Inputs and Claims

(GST/HST/PST)

PST on

Premiums

Insurance

Premium Tax

13

Commentary 522

In the insurance industry, transaction taxes –

provincial insurance premium taxes, retail sales taxes

on premiums and GST/HST/RST on claims and

operating expenses – represent about 51percent of

value added for the P&C sector, about 59 percent

for health insurance and about 17 percent for life

insurance (Figure 1). e burden of transaction

taxes is high and much higher for P&C and health

insurance than the highest HST rate (15 percent)

found in ve provinces. It is also much higher

than the burden faced on banking activities (about

3percent), which is limited to irrecoverable sales

taxes paid on operating expenses.

A Tax on Individual Wealth

All insurance products are fundamentally a form

of investment. Insurers pool the premiums from

all insureds, creating a pool of nancial resources

accumulating income that will eventually ow

out as future claims (minus the value added).

Since individuals use after-tax income to purchase

insurance, the additional taxes on the premiums are

akin to a tax on wealth.

10

Other savings instruments

such as bank deposits and bonds are not taxed

this way. Insurance purchasers are thus taxed more

heavily for the same lifetime consumption.

Higher Insurance Prices Negatively Impact

Consumer Demand

IPTs and retail sales taxes on premiums increase the

consumer price of insurance. Higher tax-inclusive

insurance premiums in turn worsen the problem of

adverse selection in insurance markets, increasing

the pressure on premiums as lower-risk consumers

are driven out of the market.

In our modern tax system, commodity excise

taxes are usually reserved for products such as

10 Note that various types of insurance purchases by business entities are deductible in many business-related situations.

11 Excluding the territories.

carbon-intensive fuel, alcohol and tobacco – all

products for which more consumption yields social

problems. But nancial protection against the risks

of large nancial losses, health-related expenditures,

morbidity or mortality, on the contrary, makes

insurance generally socially benecial.

e extent to which higher tax-inclusive

premiums reduce consumer demand is an empirical

question dicult to resolve due to lack of reliable

historical data. e market for individual life

insurance may be a good one to explore since we

would expect prices to impact consumer demand:

purchase decisions are made on an individual basis,

are typically funded with after-tax dollars and are

free from regulatory or institutional requirements.

Using a regression analysis (see Appendix

B), we isolate the impact of provincial IPTs on

individual life insurance purchases by controlling

for the potential impact of household income,

mortality, population aging, number of dependents

at home, ination and real interest rates, as well as

for province- and year-xed eects. We nd that

higher IPT rates are indeed associated with lower

demand for new individual life insurance policies.

However, little provincial and annual variation

among IPT rates, along with data limitations,

restricts the extent to which we can model the

underlying relationship in our data. But the results

are nonetheless statistically signicant. As it stands,

the model indicates that a one-percentage-point

increase (decrease) in the IPT rate would lead

to a more than a 10 percent national

11

decrease

(increase) in sales of individual life insurance

contracts. Using 2016 data, that decrease represents

about 77,000 policies, or $27 billion of potential

benet coverage.

14

Policy Options

Provinces need to think hard about the tax burden

they are imposing on insurance and its impact on

people. So, what should governments do?

Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba and Newfoundland

and Labrador, for example, should lead the way

by eliminating their punitive RST on premiums

(Chen and Mintz 2001). In addition, all provinces

should eliminate their insurance premium taxes

or, at a minimum, make them creditable against

downstream insurers’ corporate tax liability on

capital and income.

Premium taxes, however, generate so much

revenue that any attempt to eliminate or lower the

tax burden will be met with resistance. Some of

that could be alleviated by making the elimination

of premium taxes part of a more ambitious reform

of the current patchwork of transaction taxes for

insurance services.

Fiscal losses could be partly oset by charging

a tax on the value-added portion embedded in the

premiums (through, for instance, the addition-

based method), with a credit for sales taxes paid

by insurance providers on operating expenses and

claims. Essentially, this would translate into a

provincial VAT for the insurance industry. But such

a system would come with its own set of hurdles to

overcome.

In particular, the federal government does not

impose GST on nancial services, so the HST

rate would not be the most appropriate rate to

apply. Each province would need to legislate its

own insurance value-added tax rate. In addition,

assuming that provinces tax value added in

the insurance industry, there is no obvious

reason for leaving out value added from other –

currently untaxed – nancial services, including

deposit and credit intermediation, and for the

federal government to imitate the provinces. A

comprehensive and broad-based, value-added

tax system for the nancial services sector would

nonetheless bring down the insurance sector’s total

transaction tax burden from its current range of

17 percent to 59 percent of value added to levels

more comparable to that of other services subject

to the HST– and a more equal sharing of the total

transaction tax burden among nancial service

sector participants.

Conclusion

Insurance is one of the most heavily taxed nancial

services in Canada, with multiple taxes charged on

its prots, investment income and capital, as well

as on transactions such as premiums and claim

payments. ese transaction taxes on money going

in (premiums) and on money going out (operational

expenses and claims) compound to reach nearly

60 percent of insurance value added, which is on

top of the taxes the insurance industry pays on

corporate income and capital.

Premium-based taxes increase the price of

insurance products for consumers and lower

the demand for them. More specically, we nd

that an increase of one percentage point in the

provincial IPT rate leads to a 10 percent decrease

in the number of life insurance contracts sold. It is

reasonable to assume that higher prices would also

negatively impact the demand for other insurance

products. Reduced insurance coverage for natural

disasters such as oods and earthquakes, other

catastrophes, relief to a deceased’s family, or relief

of the nancial burden of illness and disability may

lead to increased cost pressures on government

budgets down the road.

Canadian governments should revisit and

reassess the taxes imposed on insurance products.

At a minimum, IPT liabilities should be made

creditable against corporate income tax liabilities,

partly restoring their original role as a substitute for

taxing prots. And provinces that impose an RST

on IPT-inclusive premiums should lead the way

and eliminate this form of double taxation. A more

ambitious reform would remodel the patchwork

of transaction taxes for insurance services to a

comprehensive and broad-based, value-added

system, bringing down the insurance industry’s

15

Commentary 522

high transaction tax burden and ensuring greater

comparability with other industries.

e tax system has evolved considerably since

IPTs were rst introduced in the early 1900s.

Now is the time to bring the obsolete taxation of

insurance premiums into the 21st century.

16

Table A1: European Indirect Taxation on Insurance Contracts

Country Tax Basis

Person Liable to Tax

Informing the Policyholder Premium Tax Parascal Tax

Established in

Country

Not Established

Austria Total amount of premium paid.

Insurer, if he nominated an agent. Policyholder, if

insurer has not nominated an agent.

Taxes not shown separately from

the premium.

Yes Fire insurance

Belgium

Total amount of premium plus

commission and collection charges.

Base for parascal taxes does not include

premium taxes.

Insurer

Policyholder in absence

of intermediary residing

in Belgium.

Taxes shown separately in motor

vehicle insurance – no provision

for other classes.

Accidents at

work are exempt.

All but life

insurance

Bulgaria Total amount of premium paid.

Insurer and tax representatives of insurers

working under the freedom-to-provide services.

Mandatory to specify tax

separately from the insurance

premium.

Life and rent

insurance

exempt. All else

is 2%.

No

Croatia Total amount of premium paid. Insurer

Shown separately from the

premium.

Only motor

insurance.

All

Cyprus

a

Total amount of gross premiums for life

insurance.

Insurer Not shown on insurance policy.

Life insurance

only.

No

Czech Republic Yearly premium income. Insurer Parascal tax not shown separately. No premium tax. Motor liability

Denmark

Does not include broker’s or agent’s

commission.

Parascal tax base does not include

premium tax.

Insurer liable, but the

insured jointly and

severally responsible

for payment.

Tax representative

Shown separately from the

premium.

1.1% premium

tax on all

contracts except

life insurance and

work-accident

insurance.

Fire insurance

Finland

Includes broker’s and agent’s commission

unless broker’s commission billed

separately.

Insurer Policyholder Premiums inclusive of premium tax.

Life, accident

and health are

exempt.

Fire insurance

France Stipulated sums beneting the insurer.

Insurer, but the insurer, intermediary or

policyholder jointly and severally liable for

payment of tax when appropriate.

No provisions on indicating

parascal tax separately.

Life exempt. Motor insurance

Germany

Total amount of the premium plus

advances, additional payments, etc.

Policyholder

(declared and remitted by the insurer or

paying-in agent)

Obligation to show the tax rate,

tax amount and tax number on the

invoice.

Life and health

are exempt.

Fire, residential-

building and

home-contents

insurance.

Greece Premiums and policy duties.

Insurer. If non-payment,

no one else is liable.

No provisions for non-

established insurers.

Insured knows amount of tax.

Life >10 years is

exempt.

Life and motor

insurance.

Note:

a Cyprus also charges stamp duty on all new policies.

Appendix A

17

Commentary 522

Hungary Insurance premiums

Premium tax paid by insurance companies.

Accident (motor tax) paid by policyholder.

No information provided to

insured about tax.

Life and health

are exempt

Motor liability

Iceland

b

No premium tax. Only parascal, broker’s

and agent’s commission included.

Insurer

Taxes indicated separately from

the amount of the premium.

No Fire insurance

Ireland

c

On assessable amount of premium

income.

d

Insurer Tax deductions notied separately.

Additional 2%

tax over premium

tax on non-life.

None

Italy

Premium, w/out deductions, and all

additional amounts paid to insurer.

Insurer Insured

Must be indicated separately from

taxable premium.

Life is exempt

after January

2001.

None for

life, health

and personal

accident.

Liechtenstein Stamp duty calculated on net premium.

Insurer -if failure of

payment, no other

person is jointly and

severally responsible for

the payment.

If insurer not subject to

Liechtenstein or Swiss

control, the insured

pays.

If insurance purchased

from representative

under Liechtenstein

or Swiss control,

representative pays.

Tax not shown separately from

premium in liability and multi-risk

motor insurance. It is separate for

other insurances.

None – only

stamp duty on

specic classes of

life insurance.

None

Luxembourg

Tax basis includes costs and commissions.

For parascal tax, basis does not include

premium tax.

Insurer

If insurer not available,

the tax representative

and the policyholder

are liable. For re

insurance, only the tax

representative is.

e

Insurer liable for

re-brigade tax;

policyholder liable for

premium tax.

Tax is shown specically on

written proposals and renewal

notices.

Life, pension,

disability,

capitalization

and motor third-

party liability

(MPTL) are

exempt.

Fire and MPTL

Table A1: Continued

Country Tax Basis

Person Liable to Tax

Informing the Policyholder Premium Tax Parascal Tax

Established in

Country

Not Established

Notes:

b In 2014, Iceland abolished all previously applicable stamp duties on insurance policies.

c Ireland has a stamp duty per new contract on non-life insurance contracts..

d Assessable amount is the gross amount of premiums received in respect of business in Ireland, excluding pensions business.

e Some insurers are required to designate a tax representative in their territory to supervise the collection of the taxes and the method of recovery.

18

Malta

Long-term life policies not renewed

annually: 0.1% on sum insured. Life

policies renewed annually: 10% on

annual premium.

Non-life policies: 11% on the annual

premium.

Insurer’s liability of

document duty on

behalf of policyholder.

Same taxation regime

applies only for policies

covering risk within

Malta.

Insured is informed of document

duty by note on the receipt.

None, Malta

levies a stamp

duty rate instead,

from which

health insurance

is exempt.

None

e

Netherlands

Total premium amount charged to

insured, including the remuneration for

services associated with insurance.

Underwriting agent/

intermediary involved

in contract. If neither

involved, then insurer.

If none of them pays,

then tax is levied from

the policyholder.

e insurer’s legal

representative,

underwriting agent or

intermediary involved in

concluding the contract.

If none involved, the

insurer is liable, or

he can assign a tax

representative to be

liable.

Tax can be shown separately from

the premium, but it is not legally

required.

Life, vehicle

registered in

another EU

country, health

and individual

accident are

exempt.

None

Poland

Poland does not charge IPT. ere is only general income taxation (19%) for legal persons, which include insurance companies and intermediaries – mutual insurance

companies excluded.

Portugal

Stamp duty: gross premium.

Parascal taxes: diers based on specic

tax.

At the insured expense:

stamp duty, FAT,

ANPC, INEM and

FGA.

f

At the insurer expense:

ASF and FAT.

g

Tax representative

Tax indicated separately from

premium.

No IPT, only

stamp duty and

parascal taxes.

Yes

Romania Total cashed premiums. Insurer No provisions reported. Yes None

Slovakia

Premium received previous year – valid

for new contracts signed after 2016.

Insurer

Taxes not shown separately from

the premium. Contracts don’t

include any information.

On non-life

insurance (except

MTPL).

MTPL

Slovenia Total premium to be paid by the insured. Insurer

Premium tax is shown separately

from the premium.

Co-payment

health and

compulsory

social insurance

are exempt.

h

Fire insurance

Table A1: Continued

Country Tax Basis

Person Liable to Tax

Informing the Policyholder Premium Tax Parascal Tax

Established in

Country

Not Established

Note:

f FAT: Workers’ compensation fund. ANPC: National authority for civil protection. INEM: National institute of medical emergency. FGA: Motor guarantee fund.

g ASF: Portuguese insurance supervisory authority.

h Premium tax is on contracts that are of a maximum duration of fewer than 10 years. If more than 10 years, they are tax free.

19

Commentary 522

Spain Total premium to be paid by the insured. Insurer

Premium tax is shown separately

from the premium.

Life, group

pensions, health,

compulsory

social insurance

are exempt.

None on life,

group pensions,

compulsory

social insurance.

Sweden

Group life: 95% of total premium by

employer to insurer.

Motor: premium.

insurer

Group life: employer.

Motor: insurer/tax

representative.

Group life: must inform

policyholder of related principal

tax features.

Motor: no obligations to inform.

Only on group

life and motor

insurance.

None

Switzerland Stamp duty base is premium. Insurer only

If insurer not subject

to Swiss control, the

insured.

Otherwise, tax

representative.

If policyholder charged with stamp

duty, premium bill must bear the

remark “stamp duty included.”

None – only

stamp duty.

i

None

United

kingdom

j

Includes the risk insured, administration

costs charged to policyholders, broker’s

and agent’s commissions and any charge

for credit.

Insurer/taxable

intermediary

Insurer (or taxable

intermediary) and

tax representative

(who the insurer may,

but not required to,

appoint) jointly and

severally responsible for

payment.

Premiums are inclusive of premium

tax – no obligation to identify

amount separately to policyholder.

Life and

pensions, marine,

aviation and

transport (MAT)

are exempt.

Exempt

Table A1: Continued

Country Tax Basis

Person Liable to Tax

Informing the Policyholder Premium Tax Parascal Tax

Established in

Country

Not Established

Notes:

i Stamp duty only on specic classes of life insurance. If the policyholder is located outside of Switzerland, then the policy is exempt from stamp duty.

j e standard rate of insurance premium tax in the UK increased to 12% in eect from 1 June 2017.

Source: Insurance Europe, Indirect Taxation on Insurance Contracts in Europe, May 2017.

20

Appendix B: Estimating the impact of IPT on sales of new

individual life insurance contracts

In our analysis, we test the hypothesis that higher IPT rates lead to lower sales of individual life insurance

contracts.

Our database consists of annual provincial individual life insurance sales and provincial insurance

premium tax (IPT) rates from 1994 to 2016 for all 10 provinces. We also use additional data to control

for other determinants such as income levels, provincial ination, mortality, real interest rates, population

aging and number of dependents. In total, we have 220 observations.

12

Table B1 shows the results of estimating the following Fixed-Eects OLS model:

IndLifeSoldPC_it

=α+β

1

* IPT

it

+β

2

* LIncPC

it

+β

3

*Ination

it

+β

4

* rrb

t

+β

5

*mortality

it

+β

6

*depratio15

it

+β

7

*depratio65

it

+μ

i

+θ

t

+u

it

where IndLifeSoldPC is the number of individual life insurance contracts sold per capita in province i

at time t; IPT is the insurance premium tax rate; IncPC is real household disposable income per capita;

Ination is the ination rate; rrb is the federal real return bond rate; mortality is the mortality rate for

those older than 30; depratio15 is the young dependency ratio for those under 15; depratio65 is the

old dependency ratio for those above 65; μ is province xed eects; θ is year xed eects and u is an

error term.

ese determinants are widely used in studies such as Yaari (1965) and Hakansson (1969) who were rst

to develop a model to explain demand for life insurance, as well as Fortune (1973), Lewis (1989), Browne

and Kim (1993), Outreville (1996), Hwang and Gao (2003), Beck and Webb (2003), Li et al (2007)

and Mapharing, Otuteye and Radikoko (2016). In cross-country studies, other variables are sometimes

included, such as education, civil rights, religion and corruption.

Our results are consistent with our expectations based on previous studies, with the addition of the

IPT rates. e explanation for our positive coecient on income should be straightforward (Table B1). It

is consistent with the literature – higher income increases aordability of life insurance and the need to

absorb surplus wealth (Campbell 1980, Lewis 1989, Beenstock et al 1986, Truett and Truett 1990, Browne

and Kim 1993, Outreville1996, Beck and Webb 2003).

e negative coecient on ination is also widely agreed upon, as it dampens the demand for life

insurance products (Lenten and Rulli 2006, Li et al 2007, Beck and Webb 2003, Outreville 1996,

Mapharing, Otuteye and Radikoko 2016). While the literature shows that the eect of interest rates has

been more ambiguous, our positive coecient corresponds with the general view that higher rates decrease

the cost of new insurance policies and increase their consumption (Beck and Webb 2003).

12 One outlier data point was dropped due to its very large departure from the mean, as is standard statistical practice. Still, its

inclusion would not result in any signicant change to our results.

21

Commentary 522

Previous studies have shown that mortality has

been mostly found to be positively correlated with

demand for insurance, as it is in our results. A higher

mortality rate and lower life expectancy, which are

used as proxies for probabilities of death, increase the

perceived need for mortality coverage (Lewis 1989,

Levy et al 1988, Beck and Webb 2003, Lim and

Haberman 2004, Mapharing et al 2016).

As for the dependency ratios, the relationships

are not as clear. Some studies show that the

demand for life insurance increases with the

number of dependents (Lewis 1989, Campbell

1980, Li et al 2007). However, other studies support

our negative coecients. When we consider the

young dependency ratio, a higher number indicates

a younger population, which needs less salary

protection against early death and often cannot

aord insurance products (Beck and Webb 2003,

Kjosevski 2012). As for the old dependency ratio,

the older you are, the higher the price, leading to

lower demand.

e data for this analysis consists of the

Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association’s

annual panel data from 1994 to 2016. Most of our

control variables are signicant at the 95 percent

condence level or higher, including our main

variable of interest, the IPT rate.

As it stands, the model indicates that a one-percentage-point increase in the IPT rate leads to a

decrease in the number of insurance contracts sold of 0.00212 per capita. Nationally,

13

this would imply a

76,797 reduction in 2016 sales of individual life insurance contracts, representing more than 10 percent of

total individual life insurance contracts sold that year.

Due to low variation in some of our variables, mainly and most importantly in the IPT rates across

provinces and over the time horizon of our data, along with other data limitations, we believe that

including too many controls (including province- and year-xed eects) reduces the impact of our main

explanatory variable.

Over the time horizon of our data (1994-2016), some provinces never changed their tax rate (BC and

New Brunswick, for example). In other cases, some provinces only raised it once, such as Alberta.

Table B1: Individual Life Insurance per Capita

Standard errors in brackets

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

Note: Constant, province xed eect, and year xed eect

coecients not reported here.

Source: Authors’ calculations. Source les available upon request.

Fixed Eects Panel

Regression

P-Values

Insurance Premium Tax -0.00212** [0.041]

Income Per Capita 0.00965 [0.230]

Ination -0.000387 [0.103]

Real Bond Rate 0.00916** [0.011]

Rate of Mortality >30 0.00317*** [0.003]

Dependency Ratio <15 -0.132** [0.011]

Dependency Ratio >65 -0.126*** [0.002]

Observations 219

Adjusted R2 0.749

13 Excluding the territories.

22

REFERENCES

Albrecht, J., Dalton and Stephen J. Rukavina. 2016.

“Insurance, Warranty and Maintenance Contracts:

Tax to the Max (More?)” EY Law LLP, 2016 CPA

Commodity Tax Symposium.

Barham, V., S. Poddar, and J. Whalley. 1987. “e Tax

Treatment of Insurance Under a Consumption Type,

Destination Basis VAT.” National Tax Journal 40(2),

171-182. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/

stable/41788655.

Beck, orsten, and Ian Webb. 2003.” Economic,

Demographic, and Institutional Determinants of

Life Insurance Consumption across countries.”

Washington, DC: World Bank.

Beenstock, Michael, Gerry Dickinson, and Sajay

Khajuria. 1986. “e Determination of Life

Premiums: An International Cross-Section Analysis

1970-1981.” Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 5:

261-270.

Browne, M., and K. Kim. 1993.” An International

Analysis of Life Insurance Demand.” e

Journal of Risk and Insurance 60(4), 616-634.

doi:10.2307/253382.

Campbell, R. A. 1980. “e Demand for Life Insurance:

An Application of the Economics of Uncertainty.”

Journal of Finance, 35: 1155-1172.

Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association.

2017. “Canadian life and Health Insurance Facts.”

Available at: http://clhia.uberip.com/i/878840-

canadian-life-and-health-insurance-facts-2017/0.

Canada Revenue Agency. 2014. “Notice to Brokers,

Agents, Insured and Insurers” Excise Tax Act – Part

I. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-

agency/services/forms-publications/publications/

rc4634/notice-brokers-agents-insured-insurers.html.

Chen, Duanjie, and Jack Mintz. 2001. “An Analysis

of the Impact of Premium and Capital Taxes on

the Property and Casualty Insurance Industry in

Canada.” Insurance Bureau of Canada. March.

Ernst and Young. 2015. “Global Insurance Premium

Tax Newsletter.” Available at: https://www.ey.com/

Publication/vwLUAssets/EY-global-insurance-

premium-tax-newsletter-issue-2/$FILE/EY-global-

insurance-premium-tax-newsletter.pdf.

_____________. 2016. “Global Insurance Premium

Tax Newsletter.” Available at: https://www.ey.com/

Publication/vwLUAssets/EY-global-insurance-

premium-tax-ipt-newsletter/$FILE/EY-global-

insurance-premium-tax-ipt-newsletter.pdf.

Firth, M., and K. McKenzie. 2012. “e GST and

Financial Services: Pausing for Perspective.” e

School of Public Policy Publications. 5. doi:https://

doi.org/10.11575/sppp.v5i0.42399.

Fortune, Peter. 1973. “A eory of Optimal Life

Insurance: Development and Tests.” Journal of

Finance 27: 587-600.

Hakansson, N. H. 1969. “Optimal Investment and

Consumption Strategies Under Risk, and Uncertain

Lifetime and Insurance.” International Economic

Review 10: 443-466.

Hwang, Tienyu, and Simon Gao. 2003. “e

determinants of the demand for life insurance in an

emerging economy – the case of China.” Managerial

Finance 29 (5/6):82-96.

International Monetary Fund. 2010. “A Fair and

Substantial Contribution by the Financial Sector:

Final Report for the G-20.” Washington, DC. June.

Insurance Bureau of Canada. 2017. “Facts of the

Property and Casualty Insurance Industry in

Canada.” Available at: http://assets.ibc.ca/

Documents/Facts%20Book/Facts_Book/2017/Fact-

Book-2017.pdf.

Insurance Europe. 2017. “Indirect Taxation on Insurance

Contracts in Europe.” Available at: https://checkout.

insuranceeurope.eu/product/1e6288bf/indirect-

taxation-on-insurance-c.

23

Commentary 522

Lenten, Liam, and David Rulli. 2006. “A Time-

Series Analysis of the Demand for Life Insurance

Companies in Australia: An Unobserved

Components Approach.” Australian Journal of

Management 31 (1): 41-66.

Levy, H., J.L. Simon, and N.A. Doherty. 1988. “Optimal

term life insurance-A practical solution.” Insurance

Mathematics and Economics 7(2): 81–93.

Lewis, Frank D. 1989. “Dependents and the Demand

for Life Insurance.” American Economic Review 79:

452-466.

Li, D. et al. 2007. “e Demand for Life Insurance in

OECD Countries.” Journal of Risk and Insurance 74:

637-652.

Mapharing, M., E. Otuteye, and I. Radikoko. 2016.

“Determinants of Demand for Life Insurance:

e Case of Canada.” Journal of Comparative

International Management 18 (2).

Outreville, Francois J. 1990. “e Economic Signicance

of Insurance Markets in Developing Countries.”

Journal of Risk and Insurance 57: 487-498.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. 2017. “Insurance Industry.”

Available at: https://www.pwc.com/ca/en/insurance/

publications/pwc-insurance-industry-key-tax-rates-

and-updates-canada-2017-09-en.pdf.

Provincial Budget Round-Up. 1957. Canadian Tax

Journal 5 (2): 113-114.

Truett, Dale B., and Lila J. Truett. 1990. “e Demand

for Life Insurance in Mexico and the United States:

A Comparative Study.” Journal of Risk and Insurance

57: 321-328.

Wark, Kevin, and Michael O’Connor. 2016. “e Next

Phase of Life Insurance Policyholder Taxation Is

Nigh.” Canadian Tax Journal 64 (4).

Weber, Matthias, and Arthur Schram. 2013. “e Non-

Equivalence of Labor Market Taxes: A Real-Eort

Experiment.” Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper.

Amsterdam: Tinbergen Institute. February.

Whaley, Raymond L., 1970. e Taxation of Insurance

in Canada, Canadian Tax Journal 18 (3): 234-261.

Yaari, Menahem E. 1965. “Uncertain Lifetime, Life

Insurance, and the eory of the Consumer.” Review

of Economic Studies 32 (2): 137-150.

Notes:

Support the Institute

For more information on supporting the C.D. Howe Institute’s vital policy work, through charitable giving or

membership, please go to www.cdhowe.org or call 416-865-1904. Learn more about the Institute’s activities and

how to make a donation at the same time. You will receive a tax receipt for your gift.

A Reputation for Independent, Nonpartisan Research

e C.D. Howe Institute’s reputation for independent, reasoned and relevant public policy research of the

highest quality is its chief asset, and underpins the credibility and eectiveness of its work. Independence and

nonpartisanship are core Institute values that inform its approach to research, guide the actions of its professional

sta and limit the types of nancial contributions that the Institute will accept.

For our full Independence and Nonpartisanship Policy go to www.cdhowe.org.

Recent C.D. Howe Institute Publications

September 2018 Laurin, Alexandre. “Unhappy Returns: A Preliminary Estimate of Taxpayer Responsiveness

to the 2016 Top Tax Rate Hike.” C.D. Howe Institute E-Brief.

September 2018 Ezra, David Don. Making the Money Last: e Case for Oering Pure Longevity Insurance to

Retiring Canadians. C.D. Howe Institute Commentary 521.

September 2018 Robson, William B.P., Jeremy Kronick, and Jacob Kim. Tooling Up: Canada Needs More Robust

Capital Investment. C.D. Howe Institute Commentary 520.