University of Mississippi University of Mississippi

eGrove eGrove

Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School

2012

Serializing the Middle Ages: Television and the (Re)Production of Serializing the Middle Ages: Television and the (Re)Production of

Pop Culture Medievalisms Pop Culture Medievalisms

Sara McClendon Knight

Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd

Part of the Medieval Studies Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Knight, Sara McClendon, "Serializing the Middle Ages: Television and the (Re)Production of Pop Culture

Medievalisms" (2012).

Electronic Theses and Dissertations

. 170.

https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/170

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information,

please contact [email protected].

SERIALIZING THE MIDDLE AGES: TELEVISION AND THE (RE)PRODUCTION OF POP

CULTURE MEDIEVALISMS

A Thesis

presented in partial fulfillment of requirements

for the degree of Master of Arts

in the Department of English

The University of Mississippi

by

Sara McClendon Knight

May 2012

Copyright Sara McClendon Knight 2012

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

ABSTRACT

Umberto Eco famously quipit

some twenty years after its publication; there is indeed something about the Middle Ages that

continues to fascinate our postmodern society. One of the most tangible ways this interest

manifests itself is through our media. This project explores some of the ways that representations

of the medieval past function within present-day reimaginings in the media. More specifically,

, and virtually untapped scholarly

potential offer an excellent medium through which to analyze pop culture medievalismsthe

creative tensions that exists between medieval culture and the way it is reimagined, recreated, or

reproduced in the present. By using medievalist studies of cinema as a model, I argue that many

of the medievalist representations on television are similar to those found in film. At the same

time, the serialized narrative structure of most television programs alters

of the past in a way that separates medievalist television from medievalist cinema. Incorporating

the evaluative tools of medievalism studies and television narratology, this project explores the

medievalisms of three narratively diverse television programsThe Pillars of the Earth

(medievalist miniseries), True Blood (series with medievalist storyline), and Game of Thrones

(fantastic neomedievalist series). Ultimately, these programs serve as case studies to demonstrate

how the varied visual and narrative treatment of the Middle Ages on television can reveal

cultural desires and anxieties about the medieval past and the postmodern present.

iii

DEDICATION

This work is dedicated to my familyMom, Dad, Matthew, and, of course, Joseph

whose love and support made this project possible.

iv

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Dr. Mary Hayes for her expert guidance, support, and

encouragement throughout this process. I would also like to thank Dr. Deborah Barker and Dr.

Gregory Heyworth for their insightful critiques of this work.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ii

.iii

ACKNOWLEDG..iv

L...vi

I. INTRODUCTION: MEDIEVALISM AND TELEVISION.1

II. THE (DE)CONSTRUCTION OF ICONIC MEDIVAL PIETY IN

THE PILLARS OF THE EARTH ... 23

III. TDIEVAL ON TVVIKINGS, VAMPIRES, AND

QUEER VENGEANCE IN TRUE BLOOD

NARRATIVE 46

IV. ORLD WE HAVEN'T SEEN FANTASTIC NEOMEDIEVALISM

OF GAME OF THRONES 66

V. CONCLUSION: ENJOY YOUR MIDDLE AGES!... 95

BIBLIOGRAPHY.. 100

VITA 109

vi

LIST OF FIGURES

1. Opening credits for The Pillars of the Earth9

2. Wells Cathedral, Somerset, E9

3. Weeping Statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary from The Pillars of the Earth 35

4. Bishop Waleran Bigod from The Pillars of the Earth 43

5. Prior Phillip from The Pillars of the Earth..43

6. Eric Northman and the Viking Crown from True Blood50

7. True Blood50

8. True Blood7

9. True Blood65

10. Queen Cersei and Joffrey Baratheon from Game of Thrones81

11. The Game of Chess from The Seventh Seal81

12. Daenerys Targaryen and Her Dragon Hatchling from Game of Thrones85

13. Sean Bean as Boromir from The Fellowship of the Ring 91

14. Sean Bean as Lord Eddard Stark from Game of Thrones91

15. The Simpsons Parody Game of Thrones. 94

1

I. INTRODUCTION: MEDIEVALISM AND TELEVSION

philosopher, philologist, medieval

studies scholar, and bestselling writer Umberto Eco delineates some of the ways that the Middle

Ages continue to exist within present-day cultural memory. Perhaps most famously he quips in

this chapter that ment still

strikes a resonant chord some twenty years after its publication; there is indeed something about

the Middle Ages that continues to fascinate our postmodern society. One of the most tangible

ways this interest manifests itself is through our media, particularly in the widespread visual

(re)productions of the medieval past. A causal Google search illustrates this point;

results.

1

The sheer quantity and variety of visually-based material on the Internet described as

medieval or as dealing with the Middle Ages suggests not only that people are actively

reimagining the Middle Ages online but also that people are actively searching for it. Probing

examples from present-day media like the Internet emphasizes the question at the heart of this

phenomenon: Why does such an interest in the Middle Ages persist? Furthermore, what can the

variety of present-day medieval appropriations and representations reveal about the relationship

between the past and the present? Even though such questions would be difficult to answer

definitively, this project will explore some of the ways that representations of the medieval past

1

Accessed 16 December 2011. This search tellingly reveals some of the numerous ways we have refashioned

the public encyclopedia Wikipedia, t

culture icon Michael Jackson yields roughly 380 million results.

2

function within present-

obvious visual textuality, widespread popularity, and influence on other media like the Internet

offers a complex medium that has not received much scholarly analysis, this project will

investigate the multifaceted relationship between television and medievalism, or representations

of the medieval past in the present.

Because this project focuses primarily on present-day representations of the medieval

past, it falls squarely within the recent surge of medievalism studies. Even though medievalism

is a slippery term that has been the source of much scholarly debate, one might say that

study of the many ways in which modern society and its popular culture

interacts with, interprets, and both influences and is influenced by the actual history of the

the fields of

medievalism studies and medieval studies differ. Rather than being concerned only with

actualities of the history, literature,

2

medievalism

studies instead attempts to understand the ways that these actualities have been remade over

time. In other words, the emphasis shifts from analyzing medieval culture in its historical context

(medieval studies) to analyzing how medieval culture influences or is used by the present.

The process of investigating medievalisms hinges upon the fundamental notion that the

past is never singular or stable, but is instead continuously recreated and reproduced during each

present moment. A multifaceted medieval past explodes into exponentially diverse medievalist

3

2

there is always an aspect of subjectivity

in scholarship, whether intentional or not. The crux, then, of medieval scholarship is that we must rely on and

interpret cultural artifacts to gain insight into the past. This very act of interpretation thus opens all medieval

scholarship up to skepticism regarding subjectivity. This is not to say that medieval scholarship should be

disregarded because it is inherently subjective, but rather that we must remember that academic inquiry into the

perspective regarding medieval artifacts.

3

to describe something that possesses attributes of medievalism. I refer to those who study the Middle Ages as

3

representations of it in each passing present, where the layers of medievalist reproductions

diverge, converge, and/or build on top of one another to create something that is paradoxically

both old and new. Speaking to this very notion, David Marshall in Mass Market Medieval:

Essays on the Middle Ages in Popular Culture offers that scholars of medievalism should see the

e

generation continues to augment in hopes of paradoxically (re)creating something that is more

. Over time, these

constructions build on top of one another like thick layers of paint so much so that it seems

impossible to get back to the original shade. Consequently, medievalism studies interrogates

these complex, often sedimentary relationships between the actualities of medieval history or

contemporary medieval representations of the Middle Ages through its art, architecture and

literature, and the present-day (re)constructions of these fragmentary, plural pasts.

Of course, the past/present negotiations that drive the study of medievalism are nothing

new. The Romans looked back to the Greeks, medieval thinkers pondered the philosophical and

mythological writings of antiquity, and hosts of generations have combed the Middle Ages for

clues about their origins (Bull 101). Perhaps as medievalism scholar Angela Jane Weisl suggests,

separates itself from that past . . . [reveals a] desire to reinforce comforting, if problematic,

values of the past within the seemingly moder15). If people find

comfort and wisdom in examining the past, then surely this comfort is rooted in the perceived

medievalism studies scholars to maintain

clarity.

4

cyclical nature of history. The idea that historical patterns in culture repeat themselves enables

the present to be grounded in a sense of tradition, even if that tradition has become unpopular.

4

In a broad sense, medievalisms then incorporate both the ways that cultural patterns and

traditions are evoked in new contexts and the motives behind such evocations. Medievalism

studies thus not only questions temporal relationships but also interrogates the presentist

ideologies inborn in these relationships.

Interestingly, this question of the ideologies behind medievalist (re)creations has forced

some (at times uncomfortable) reconsiderations within the field of medieval studies. Works like

The Shock of Medievalism argue that the advent of medievalism scholarship

revealed conservative ideologies hidden within medieval studies dating back to its nascent years

in the nineteenth-century. In suggesting that some present-day medievalists are continuing to

ignore their own motivationsmainly avoiding engagement with critical theory

5

in favor of

romanticizing and thus alienating medieval cultureBiddick alleges that the promulgation of an

artificial temporal separation between the Middle Ages and the present inaccurately reinforces

the notion of a singular, constricting past:

4

racial purity to

Nazi attempts to legitimize their state-sponsored genocide by looking back to the medieval prowess of the Aryans

Medievalism in Europe). This is just one provocative and striking example

of how backwards-looking attempts to ground present-day ideologies in (re)created pasts often look very different

from historical actualities.

5

indictment, many scholarly works have attempted to breach the divide between theory and

medieval studies. In Lacan’s Medievalism, Erin Felicia Labbie explains how medievalism and an engagement with

critical theory (psychoanalysis in this case) can work together to create a larger picture

psychoanalytic developments attributed Lacan back to his personal exposure to medieval stories and scholarship.

Here, Labbie discusses the importance that temporality plays in subject formation:

The speaking subject is always materially bound by way of language to a given historical context.

This means that it cannot be ahistorical in any case; the subject is always situated historically and

culturally . . . The conscious understood as an abstract, conceptual entity, however, is precisely

transhistorical in that it exists in each speaking subject throughout time, whether here is a name for

it, the unconscious, or not. (9)

The Premodern Condition: Medievalism and the Making of Theory also provides an extended and

well-researched discussion of the important relationships between medieval studies and theory.

5

-

Middle Ages is suspect. These images mark a desire rigidly to separate past and

present, history and theory, medieval studies and medievalism. They foreclose

exploration of how critical theories might historicize medieval studies, theories

Without taking the necessary step to historicize medieval studies by placing both the medieval

artifact and the present-day effort to interpret it within their respective contexts, medieval studies

would be doomed to continue to falsify or ignore the temporal relationships at the heart of our

cultural obsession with the Middle Ages. Because, as Eco argues,

through both scholarly

investigation and popular reimagining

understand our present state of health, asks us about our childhood, or in the same way that the

psychoanalyst, to understand our present neuroses, makes a careful investigation of the primal

65). The temporal pull between the past and the present is the very thing that continues

to draw our attention to the Middle Ages, and thus medievalist impulses within academia should

be recognized as an integral and unavoidable part of medieval studies. In other words, scholars

of medieval culture should recognize that they too are in the business of recreating, and to some

extent, reimagining the medieval past. Medievalism studies and medieval studies necessarily go

hand in hand.

As part of the effort to historicize the fields of medieval studies and medievalism studies,

scholars must ask themselves what they want from the past.

6

If one ignores her motivations, even

in academic inquiry, then she ignores a crucial component of her research that would effectively

6

Questions of ideology are especially important as medieval scholars continue to test conservative academic

boundaries by researching new areas like queer studies and disability studies

medieval queer studies have on presen

6

and appropriately acknowledge temporal tensions. Medieval studies, after all, deals with

fragments of the past that scholars revisit at different points in the present. Some of the most

effective medieval scholarship bridges the gap between past and present by being honest about

critical motives.

7

In exploring the temporal dialectic between cultural studies and what they term

medievalism scholars Eileen Joy and Myra Seaman rightly assert

that

overly contemporary sensibilities, but rather to bring the past and present into creative tension

aptly describes the temporal pull at the heart of

medievalism. Because, as Tison Pugh argues in Queer Movie Medievalisms,

other periods find cultural parallels in both the Middle Ages and medievalist reproductions from

the Renaissance onward (12). The study of medievalism, for example, should be not limited to

Victorian interpretations of Chaucer but should also explore how present-day interpretations of

Chauce

metaphor, it can often be difficult to differentiate one addition to the medieval edifice from

another when the architectural styles are so similar. However, in seeing the multitude of

medievalist productions as a whole of parts, rather than parts of a whole, we can begin to

understand how the steady recycling of medieval and medievalist elements within our cultural

memory work both to satiate and to stimulate our desires for more medievalist productions.

7

Carolyn comes to mind as an

exemplar. Dinshaw opens the article by recalling a provocative 1990s Vanity Fair magazine cover featuring Cindy

Crawford shaving k.d. lang. Dinshaw goes on to discuss how this present-day

of the Wife of Bath and the Pardoner in

Canterbury Tales.

7

The study of medievalisms then has much to offer, but even amidst its growing

popularity within the last thirty years,

8

many scholars still seem to be arguing their case for

legitimacy. Bettina Bildhauer, who has written widely on both medieval studies and medievalism

studies, medievalism is unfairly seen as derivative and as less noteworthy than the

(14). reinforces canonical

assumptions in other areas of literary studies because, as some have argued, at least one facet of

a medievalist project is deemed One might see ClaWomen

Writers and Nineteenth-Century Medievalism or Jennifer A. Palmgren and Loretta M.

Beyond Arthurian Romances: the Reach of Victorian Medievalism as underscoring a

distinct division between acceptable objects of academic interestthose objects that are of

interest in their own right to academics beyond any medievalist inclinationsand those

Projects examining medievalist undercurrents in the likes of

Tennyson or Scott allow for the analysis of these romanticizations of the past while researching

within the comfortable space of canonical tradition.

9

The fear of academic legitimacy (and

perhaps funding) seems to have hindered the growth and acceptance of medievalism studies. Yet

restricting the study of medievalism to a few highbrow authors would effectively ignore one of

the most exciting and illuminating area of study: popular culture medievalisms.

10

8

For example, The International Society for the Study of Medievalism, established by Leslie J. Workman in 1979,

publishes a journal (Studies in Medievalism) and an annual bibliography (The Year’s Work in Medievalism), holds

The International Conference on Medievalism, and sponsors sessions at both the International Congresses on

Medieval Studies (Kalamazoo) and the International Medieval Congress (Leeds).

9

These studies do, of course, have immense scholarly value in and of themselves because they analyze earlier forms

of medievalism. At the same time, they only emphasize the high culture-low culture divide.

10

The term popular culture is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary designating forms of art, music, or

culture with general appeal; intended primarily

include forms of culture that both incorporate medieval materials and appeal to general populations.

8

As Marshall explains in Mass Market Medieval, academia tends to look down its nose at

inquiry:

Under this stigma, examining pop cultural appropriations of the medieval is

reduced to analysis o

scholar studying a pastiche, a hodge-podge representation that has neither a real

connection to the past nor any clear bearing on the present. In this way, the high-

culture/low-culture divide becomes redefined in terms of chronology . . . the

Middle Ages stands in for high culture, while pop cultural uses of it are positioned

as low, and hence unworthy of serious examination on an academic level. (5)

Although many pop culture medievalisms could be accurately described as simulacra, this does

not mean they should be ignored as Marshall believes Jameson is suggesting; rather, the unique

position of pop culture medievalismsbeyond academic, highbrow appropriations of medieval

cultureallows for fresh investigations of past/present relationships. While conceding the

necessary separation from observing subject (scholar) and object of observation (cultural

artifact), medieval studies scholar -

statu

transmission and dissemination of the representations of history within the general population.

tive curiosity that

makes it is one of the ways in which we practice thinking about

, and other proponents of the

academic study of pop culture medievalisms, one of the most obvious reservoirs of medievalist

appropriations in present-day popular culture can be found in the study of media like cinema,

9

print media like magazines, the Internet, and television. Since scholars have been predominantly

preoccupied with cinematic iterations of pop culture medievalisms a brief discussion of it will

provide a foundation for the forthcoming explorations of medievalisms on television.

MEDIEVALISM AND CINEMA

y the heritage of the past

not through hibernation rather through a constant retranslation and reuse . . . balanced

pop culture productions available to scholarly inquiry outside of literature

retranslations and reuses of the Middle Ages have become a growing area of academic interest.

11

Because

recent medievalist cinema studies will provide a helpful theoretical framework for the

considerations of medievalist television to follow.

While studies of medievalist cinema have been cropping up since the 1970s, perhaps in

conjunction with the increasing interest in cinema in general, the last ten years have been a

particularly fruitful period. Of recent publications, most studies fall within two general

categories: those concerned with the historical accuracy of cinematic medievalisms and those

concerned with the relationship between cinema theory and medievalisms. This first area of

cinematic medievalist scholarship Middle Ages from

on how

can make us think long and hard about our lives in comparison to those of

, a specialist in medievalist cinema, suggests

11

-demic findings become repackaged for mainstream audiences,

interest in medievalist cinema has become so pervasive that Wikipedia even .

10

that cinematic medievalisms are

Ages as a temporal Other while compulsively retooling imagined continuities to fit the rapidly

changing priorities Movie Medievalism 5). In this sense, tracing the

historical accuracy of medievalist representations in cinema attempts to locate the medieval

edifice underneath the present-day cinematic embellishments to demonstrate how the present has

remade the pastThe Medieval Hero on Screen or John

A Knight at the Movies: Medieval History on Film evaluate the relationships between

medieval culture and medievalist cinema in effort to theorize how popular culture has (often

badly) reinvented the past.

While this brand of medievalism scholarship certainly makes some exciting connections

between pop culture recreations and medieval culture, it typically treats the medieval past as

static while the emphasizing the transformative power of the modern (re)interpretations. But this

sort of scholarship often fails to recognize present shares with the

past; the Middle Ages should not be treated as decaying remnants of times gone by, but rather as

living history that continues to impact the present and the future. Indeed, as Bildhauer argues,

ely not to reduce it to an allegory for the present, as

either rather

than focusing on how the present uses the past for its own ends, we should also evaluate how

kernels of medievalness necessarily continue to affect the ways they are reimagined through

cultural memory. What is it, for example, about the medieval notion of a knight that continuously

draws presentist attention and catalyzes its recycling in medievalist reproductions?

11

more consistent use of the tools of film theory and formal fi,

into medieval studies can

reveal the presence of ideological undercurrents in scholarship, using the tools of film theory can

refocus the scholarly interest of cinematic medievalism onto the relationship between form and

function in these medievalist productions. A medievalist film, just like medieval scholarship,

(re)constructs the medieval past, but it does so in a uniquely audio-visual way. Medievalist

cinema

these audio-visual reconstructions expose the cultural value of medievalism and its

creative temporal tension:

Nothing medieval in a movie is an aesthetic given, passive, inert; everything is

constructed, if only by the decision to point the camera at it. Therefore everything

medieval about a movie can be useful in understanding how, through cultural

memory, we construct our view of the Middle Ages. It is not necessary to ferret

out particular anachronisms in a medieval movie in order to demonstrate that it is

not faultlessly authentic, because by definition the entire film is an anachronism.

(92)

Because medievalist cinema is necessarily anachronistic, authenticity should be of little

importance. The Middle Ages ended hundreds of years ago, so any (re)creation of them is

necessarily anachronistic. At the same time, this does not mean that the medieval sources that

perhaps inspired these audio-visual reimaginings should be ignored for, after all, these markers

are recreated by medievalist cinema. Instead, kernels of authentic

medievalness as well as anachronisms should both be evaluated within the cinematic context so

12

This second strain of medievalist cinema studies is perhaps best represented by Andrew

Remaking the Middle Ages: The Methods of Cinema and History in Portraying the

Medieval World. By applying some innovative ideas regarding cultural reproductions of the

Middle Ages put forth by François Amy de la Bretèque in L'Imaginaire médiéval dans le cinéma

occidental, Elliott presents some of the most refreshing scholarship regarding medievalist cinema

in recent memory

the present is bridged by two modes of representation: iconic and paradigmatic. Broadly, each

mode of representation looks to what a material

source of medieval culture (the kernel of medievalness) into which a film can tap to (re)create a

perspective on the Middle Ages.

12

sta

mode of representation, the audience viewing Brian HelgelandA Knight’s Tale understands

that William (Heath Ledger) is a knight because he wears armor, rides a horse, and competes in

jousting tournaments (just as knights depicted in other medieval settings).

horizontally, by assimilating its form to other, more recognizable and familiar mo(Elliott

3). Whereas iconic representations of the Middle Ages are necessarily conservative in nature

because they look back to older representations of medieval culture, paradigmatic representations

provide more leeway for new medievalist interpretations. They provide present-day audiences

with metaphoric connections between the past and the present. As Elliott puts it, paradigmatic

uivalent (or, at best, an

12

Medieval referents might include medieval literature, art, architecture, historical chronicles, or other remnants of

medieval culture. This notion does somewhat problematically collapse boundaries between the reality of the Middle

-

holistically, whether in words or images, this collapsing has little effect on the reimagining of medievalness in

medievalisms.

13

approximation) structural relationships of the Middle Ages are brought forward into

the present, and re--4). In A Knight’s Tale, for example,

paradigmatic representations of the Middle Ages reach their peak during the anachronistic

jousting tournament scenes. Although the tournaments in which William competes appear to be

more of a Renaissance festival/modern football game hybrid than an accurate representation of a

historical joust, present-day audiences can perhaps more easily understand what the atmosphere

of such a joust was like by including present-day attributes such as a jock jams soundtrack and

vendors hawking turkey legs in the jousting stadium than if the director had consulted a hoard of

of representation work toward bringing the past and present into creative tension with one

another, the examples from A Knight’s Tale underscore crucial differences. Ultimately, iconic

representations are concerned more with historical continuitycinematic elements that spark the

while paradigmatic representations allow for creative

anachronismcinematic elements that directly yet metaphorically link the past to the present

and vice versa.

cinema specifically, extending this taxonomy to other medievalist cultural productions proves

valuable in beginning to locate the ideological underpinnings that drive pop culture

medievalisms. In particular, I would like to use

as an evaluative tool for exploring the fertile yet heretofore unharvested medievalist territory of

television programming. Like medievalist cinema, medievalist television incorporates a host of

iconic and paradigmatic representations of the Middle Ages that suggest a cultural obsession

with the past and provide an audio-visual platform for a range of present-day ideological

14

negotiations. Unlike medievalist cinema, the prevalence and popularity of serialized television

programs offers a unique opportunity to evaluate how these audio-visual medievalisms play out

in different narrative forms.

MEDIEVALISM AND TELEVISION

Although many scholars have analyzed medievalism and cinema, medievalism and

television remains virtually untouched by academiaoreword to Cultural

Studies of the Modern Middle Ages is one of a rare few publications to focus on the academic

The deep connections between medieval cultur

reality are not so whimsical or overstrained as the idea may at first appear. All

technologies serve basic and permanent human needs, and technologies of

communication serve our needs for expression, connection, influence, and

meaning. From this perspective, TV stands in an intelligible sequence with

writing, visual iconography and public art, heraldry, printed books, and

regularized postal systems. The startling juxtaposition of televised narrative with

hand-copied and read aloud medieval narrative can direct our attention even more

sharply to the permanent needs and capacities of the human mind to channel its

desires by retaining and reassembling images and information. Technologies only

serve to play out, but never resolve, the tension between reality and desire. (xiii)

-copied and

aims to explore what happens when medievalisms

meet television. I will argue that medievalist television, like medievalist cinema, should be paid

15

more scholarly attention because it can reveal how cultural desires for the past are mapped onto

present-day media productions. Rather than present some all-encompassing (and unnecessarily

essentializing) theoretical framework onto which one could map all of various

medievalisms, I have chosen instead to provide three case studies of televisions programs to

narrative diversity within the serialized program format and the variety of

medievalisms these programs (re)construct.

Much like arguments made in favor of the value of studying medievalisms thirty years

ago, the potential fruitfulness in tracing interconnectivity between theory and medievalism

twenty years ago, or the seemingly endless possibilities in exploring medievalist cinema ten

years ago, the study of medievalism and television is a worthwhile endeavor because it can

further reveal present-day ideologies. In the present case, the longstanding belief that television

has relegated it, like cinema before it, to the realm of

part-time, armchair scholarship. Even today with the growth of cultural studies as a serious

academic discipline that has effectively widened the scope of scholarly interests, television has

yet to receive the serious scholarly explorations it deserves. As television critic Jason Mittell

suggests, unlike literature or film, television rarely has pretensions toward high aesthetic value,

[thus] making it problematic to consider television using the same aesthetic tools designed for

high literatuelevision, despite ,

be evaluated. In fact, Mimi White, a scholar interested in the ideological analysis of television,

suggests that because television occupies such a prominent position in contemporary social life

with its ever-present and far-reaching influence, scholars need to evaluate it:

It is thus clearly important to subject [television] to ideological investigation.

This is especially the case as the expansion of cable and other alternative choices

16

to network and broadcast programming proliferate and fragment the audience,

offering a wider range of programming but also reduplicating much of what

already exists. (196)

Like White, I am arguing for an ideological investigation of television, specifically how and why

as simulacra on television programs.

Yet, how does such an investigation differ from similar medievalist cinema projects? To answer

this question, one first needs to assess the major difference between cinema and television.

In Everything Bad Is Good for You: How Today’s Pop Culture is Making Us Smarter,

that mass culture follows a steadily declining path toward lowest-common-denominator

standards, . . . the exact opposite is happening: the culture is getting more intellectually

demonstrates

popularized by daytime soap opera programming actually requires progressively demanding

keeping often densely interwoven

plotlines distinct in [her] head as [she] watch[es] . . . [while] making sense of information that

has been either deliberately withheld or deliberately left obscur

progressively complex mode of narrative on television, Alan Kirby notes in Digimodernism:

How New Technologies Dismantle the Postmodern and Reconfigure Our Culture that TV

program formatting has increasingly become oriented toward serialization

13

nobody cares that the Canterbury Tales

13

Both Johnson and Kirby note that serialization, or the continuance of a narrative from one episode to the next, was

originally developed by the daytime soap opera. Serialization is a distinct mode of TV narrative different from the

popular sitcom format, which has historically been more popular during primetime programming. John and Kirby

also suggest that serialization has become more pop

influence.

17

programming is that the narrative continues into the next episode (163). metaphor is

most apropos for the present considerations of the relationships between medievalism and

television because just as readers of Canterbury Tales become absorbed in and somewhat

-within-frame narrative structure, so too do viewers of serialized

television. As the old saying goes, it is not the destination, but the journey that really matters.

Serialized television provides an extended journey more or less for the sake of simply taking a

trip (or pilgrimage).

14

Thus, the major difference in terms of format between cinema and most television

programming is the serialization of TV, and consequently, this serialization affects television

medievalisms.

narrative questions are answered by the resolution to provide a sense of closure for the audience,

the that populate television programming remain just that: open;

problems, mysteries might remain unsettled or resolutions might provoke still further questions,

lies in its possibilities (Allen 107). Similar to a serialized Victorian novel, serial television

programs face particular genre dilemmas. As television scholar Sarah Kozloff argues in

must bring up to date viewers who do not usually

watch the show or who have missed an episodeenough viewer interest

and involvement to survive their hiatu91). Serial television programs can

mediate these situations in a number ways, which include but are not limited to cliffhanger

endings, interconnected subplots, flashbacks, and dreams. In theory, the open narratives of serial

14

For the sake of simplicity, I have chosen to limit my inquiry of medievalist television to serialized television

programs. However, this does not mean that other forms of television do not exhibit medievalism. Joy, Seaman, Bell

Cultural Studies of the Modern Middle Ages actually features two chapters that briefly explore

medievalism in reality TV shows like Survivor. Hopefully, more scholarship dealing with medievalist television will

appear within the next few years to continue to fill this gap.

18

television could continue infinitely, creating exponentially interwoven storylines and character

relationships. This potentiality for openness positions medievalist television in particular as a

unique cultural production within the field of medievalism because it inherently calls into

question the continuity, accuracy, ic and paradigmatic

representations in ways that the closed narratives of medievalist cinema cannot. A feature-length

medievalist film might provide audiences with two hours of iconic and paradigmatic

representations whereas one season of a serial medievalist television program might provide

twelve hours of such representations. The extended narrative format of serial television offers

those interested in the study of medievalism with an opportunity to investigate how

representations of the medieval past function over a period of time as these representations unfurl

over weeks, months and even years of programming.

Although the complexity and breadth of serial television narratives provides a wealth of

research possibilities for the field of medievalism studies, analyzing these narratives can become

complicated. TMichael Porter,

Deborah Larson, Allison Harthcock, and Kelly Berg Nellis in

offers an exciting opportunity for limiting the scope

of serial television narratives in a useable way so that the narrative function of a scene becomes

the unit of analysis applicable to the program as a whole. Porter, Larson, Harthcock and Berg

identifies specific, discrete narrative functions within a scene

that show how those scenes adv

function/purpose of this scene for the tell

function of a television major

event iinteresting but not

19

necessarily vital information for the story to move forwa(25). The primary distinction

between a kernel scene and a satellite scene lies in their respective importance to the logic of the

event would no longer bear weight on

the story; the removal of a satellite scene would not cause such a change because its functions on

the levels of background information and character development. Although it provides this

helpful distinction, the Scene Function Model also allows the exploration of multiple layers of

meaning in a single scenehow a scene can function as both a kernel and a satellite. Depending

on the characters within a given scene, their relationships to one another, and their relationships

to the story arc in general, the function of one scene can differ drastically from another in terms

of both character development and/or narrative development.

15

ene

representational schema, enable us to explore the complex relationships between the narrative

content and form, and the audio-edievalisms. Within

medievalist television programming, these narrative tools further accentuate medievalist

representations (iconic and/or paradigmatic) and their relationships with their medieval referents

and their presentist contexts because serialization requires a consistent recreation of the

medievalist representations over the course of the program. Further, because each serial

television program uses different narrative strategies to maintain an open, continuative narrative,

the continuity of the medievalist representations of each program fluctuate. Unlike most

medievalist cinema, the form of medievalist television greatly impacts its medievalisms and their

15

Indeed, Porter, Larson, Harthcock, and Berg Nellis outline six essential functions of a kernel scene and twelve

functions of a satellite scene. Using this model of scene functionality allows for greater flexibility when analyzing

relational patterns of representation, characterization, and plot.

20

functions within the narrative. Thus, the interplay between medievalist representations and

modes of serialization is the key toward theorizing television medievalisms.

In effort to consider these two important evaluative components of serialized television,

the following chapters examine three of the most recent popular medievalist television programs

in two distinct ways. First

elationship with the

Comparative analysis between these medievalist programs and medieval referents like medieval

literary and historical texts provide a more complex perspective on these representations.

Ultimately, questions of medievalist representations present in these television programs ask

Literary? Fantastical? Or something

different?

Second, by mapping the interplay between iconic and/or paradigmatic medievalist

or the ways

by using the Scene Function

Model, I hope to offer a more complex picture of medievalist

television and its purposes. Specifically, I am interested in how narrative strategies in a

miniseries, a serialized program with a limited medievalist storyline that waxes and wanes yet is

always present, and an entirely medievalist serialized program respectively affect representations

of the Middle Ages. I argue that the mode of serialization

directly bears on both the functionality of the scene and the medievalisms contained by it.

Chapter 1 focuses on the 2010 Starz eight-part miniseries The Pillars of the Earth, based

on the Ken Follett novel of the same name. I have decided to begin with this miniseries for two

21

reasons. First, The Pillars of the Earth is the most-historically rooted of the three television

programs that I evaluate; as such, the iconic medieval referents are easy to discern. Because the

miniseries plays with representations of the medieval church and clergy, chapter 1 will explore

Canterbury Tales to flesh out prominent

medieval referents like cathedrals, relics, and clerical garb. Second, because I am proposing a

theory of evaluative criteria that differs from medievalist cinema studies, I have chosen to begin

with a miniseries because it is the form of television most closely related to the closed narrative

structure of cinema. This medievalist miniseries will provide the point of differentiation between

medievalist cinema and medievalist television through its closed narrative structure from which

the remaining chapters will develop their explorations of serialized television narratives. In

ideological terms, the iconic medievalisms of The Pillars of the Earth suggests a cultural desire

for the (re)affirmation of Christian morality over canonical traditionalism.

True Blood. Even though the series, which deals primarily

with the relationships between supernatural beings like vampires, shape shifters, and werewolves

in present-day Louisiana, is not as overtly medievalist as The Pillars of the Earth, I have selected

this program for the very reason that its medievalisms are serialized in the form of a limited

medievalist narrative. Rather than presenting audiences with an entirely medievalist narrative, a

program with a limited medievalist narrative features concentrated pockets of medievalist

representations that then cause us to think of the past resurrected in the program as a whole.

Although True Blood does feature several medievalist storylines worth evaluating, chapter 2

explores the interplay between iconic and paradigmatic medieval representations in the form of

flashbacks that provide background for the suggestively named vampire Viking Eric Northman.

These flashbacks, which occur over several episodes, attempt to historicize Eric by obviously

22

and repeatedly rooting his character in the Norse tradition of the blood feud. At the same time,

homoerotic paradigmatic representations queer the traditional notion of the blood feud and reveal

True Blood-ideologies at work.

Lastly, chapter 3 provides an extension of the first two

Game of Thrones, a series that pushes medievalist television into new territory. Unlike The

Pillars of the Earth and True Blood, Game of Thrones reimagines a fantastical medieval world

full of ambiguously medieval characters. Because the entire series combines vague visual

references to other medievalisms with faintly recognizable medieval referents, chapter 3 explores

paradigmatic representations of medieval culture. Further, I argue that because

this parallel universe appears to be based on medieval culture yet does not showcase its medieval

referents as do The Pillars of the Earth or True Blood, Game of Thrones should be categorized as

a neomedievalist television series. I propose that because neomedievalism reinterprets other

medievalist interpretations of the past to create a new mythical Middle Ages, it belongs within

the postmodern notion of bricolage. This hodge-podge effect permeates many neomedievalist

productions, and thus represents a new and exciting area for scholarly investigation of pop

culture medievalisms.

efforts to explore the relationships between medievalism and television

represent one more attempt at trying to understand why people continue to return to and

(re)imagine the Middle Ages. As Eco wisely asserts, our reference point for the Middle Ages

reveals The serialized (re)production of pop culture

medievalisms on television reveals that we may just dream of a never-ending Middle Ages full

of narrative possibilities.

23

II. THE (DE)CONSTRUCTION OF ICONIC

REPRESENTATIONS OF MEDIVAL PIETY IN THE PILLARS OF THE EARTH

The tagline for the 2010 Starz medievalist miniseries The Pillars of the Earth

capitalizes on what StepMisconceptions about the

Middle Ages describes as one of the most popular misconceptions about medieval Christianity:

In the popular imagination, the medieval church was populated by fat monks

given to luxurious living, sinister popes who sought to control a superstitious laity

by keeping them ignorant of the true tenets of Christianity, and a corrupted

clergy who enriched themselves by exacting tithes from impoverished peasants

and extorting indulgence money from misguided believers. (31)

The persistent myth of medieval religion as is perhaps rooted in the

Protestant Reformation and the

Renaissance that figured medieval Christians (and the Catholic Church) as uneducated,

ingenuous, and ideologically suspect. Although numerous scholarly projects have successfully

argued that medieval piety and religious institutions cannot be described accurately in such

homogenous and stereotypical terms,

16

the popular stereotype of monolithic medieval religious

practice continues to be exploited by popular medievalisms like The Pillars of the Earth.

17

In

16

The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400-1580 or almost any

of the texts in Medieval Popular Religion: A Reader can attest to the heterodoxy of medieval

Christianity.

17

Misconception and skepticism exists within the academy as well. As medieval studies scholar Helen Cooper

-

of scholarly skepticism (xi). This skepticism appears to be aimed particularly pointedly at the less tangible aspects of

medieval pietymiracles, visions, saint cults, and mystics. For example, scholarly projects like Kroll and

24

particular, this miniseries focuses on the construction of the false monolithic icons of medieval

pietythe cathedral, the relic, and the symbolic vestments of the clergyso that it can

deconstruct them during the course of the narrative. While inaccurate in terms of historical

reality, the deconstruction of these iconic representations ironically mirrors the heterodoxy that

medieval religious scholarship has uncovered. The scenes featuring these iconic representations

of the cathedral, the relic, and the symbolism of clerical vestments notably serve singular

narrative functions as kernel scenes to reinscribe The Pillars of the Earth

own medievalisms. The of these scenes within the extended yet still

closed narrative form of the miniseries highlights the , by extension,

its dependence on iconic representations of medieval piety. Because the miniseries only has eight

episodes to develop this construction/deconstruction, it does not have the same narrative luxuries

as open-ended serial programs like True Blood and Game of Thrones to develop paradigmatic

representations over a longer story arc through the potentiality of satellite scenes becoming

kernel scenes over time. The miniseries demands that each scene further its narrative. Ultimately,

tdieval piety serve as straw men that it can knock

down both though representation and narrative in order to bring the past to bear on present-day

notions of religion.

THE PILLARS OF THE EARTH: A MEDIEVALIST MINISERIES

By beginning with the miniseries The Pillars of the Earth, this project will continue to

discuss increasingly open, serialized narrative structures in two other medievalist television

programs, True Blood and Game of Thrones, to explore the ways that different modes of

The Mystic Mind: The Psychology of Medieval Mystics and Ascetics attempt to use rationality and

mental illness to explain such phenomena.

25

serialization impact medievalist representations on television. Within the context of the

open/closed narrative theory, the miniseries provides a bridge in form from a feature-length film,

which presumably presents a beginning, middle and end in traditional closed narrative style,

21

and the open narrative represented by the serial television program, which in theory, may never

end. Although medievalist television differs from medievalist film primarily because the

miniseries develops episodically, both medievalist films and miniseries are closed narratives by

nature. Accordingly, the miniseries

action and characterization of the narrative embodied in each scene must be contained within the

narrative and logically gesture toward closure. At the same time, as its name suggests, the

miniseries does have more narrative space to develop its story. Because each iconic scene serves

a narratively important role as a kernel scene from which some future narrative consequences

will develop, the narrative structure of the miniseries reinforces the notion that these icons

themselves are crucial to the story. Moreover, the predominance of the iconic representation-as-

kernel-scene model further (de)constructs

these icons of medieval piety. Within a closed narrative, each iconic representation must

construct the icons as static (orthodoxywhat the audience might expect to see, even if

anachronistic) while also planting the seeds of the icons deconstruction (heterodoxywhat the

audience wants to see) so that the narrative fully

develops within its given space and comes to a conclusion. By incorporating the Scene Function

The Pillars of the Earth

medievalisms, we can more easily locate the presentist religious ideological negotiations that

21

Obviously, not all films are closed narratives, but film narratology is beyond the scope of this project.

26

The following summary

of the miniseries, which this chapter will discuss in detail later, demonstrates how The Pillars of

the Earth functions as a closed narrative.

The Pillars of the Earth follows the story of Tom Builder, a master mason whose

ambition is to design and build a cathedral grander than any seen before. Unable to find work,

Tom moves his family to Kingsbridge

fortuitously) burns the night before they are to move on to the next town. Tom seizes the

opportunity to present his designs for a new cathedral to the newly appointed prior, Philip, who

also wishes to build a cathedral that will glorify God and bring more worshippers by creating a

new, grander shrine for the reliquary of St. Adolphus, their adopted local saint.

22

Tom, along

with his son Alfred and adopted son, Jack Jackson, begin work on the new cathedral. All of this

-twelfth

century.

23

force Empress Maud

24

and her supporters to France. Because Stephen has the support of the

Church, namely the Archbishop of Canterbury and the scheming, ambitious Archdeacon of

Shiring, Waleran Bigod,

25

he ultimately controls England as king. During the course of the story,

the political unrest combined with , and

Jack Jackson interfere with the construction of the new Kingsbridge Cathedral. Ultimately, Jack

22

No explanation is offered as to why St. Adolphus is the adopted local saint of Kingsbridge other than the fact that

23

The Anarchy (1135-1153) is a term commonly attributed to the period of civil war over the succession of Henry I.

only legitimate (male) heir died in a mysterious shipwreck (White Ship

was ousted by Stephen of Blois, a grandson of William I. The Anarchy ended when Stephen agreed to recognize

England under the Norman and Angevin

Kings, 1075-1225 provides a helpful timeline for this period.

24

25

While Waleran Bigod is a fictitious character, his name certainly recalls Hugh Bigod, an English nobleman of the

same period who continually changed allegiances over the course of the conflict between Stephen and Matilda. Marc

The Bigod Earls of Norfolk in the Thirteenth Century

through later English history.

27

is able to bring back a miraculous relic from Francea statue of the Virgin Mary that weeps real

tearsso that the priory can raise enough money to pay for the remaining construction costs

through the offerings brought in by pilgrims. As Waleran tries one final time to halt the

construction of the cathedral with an erroneous heresy and murder trial of Jack, now master

builder, Waleran is exposed as the orchestrator of the White Ship disaster, which plunged

England into civil war. As the mob of angry citizens challenge Waleran, he desperately climbs

the near-complete Kingsbridge Cathedral, ultimately choosing to fall from the height of the

outstretched hand and the punishment that surely awaits him.

This brief synopsis suggests a wealth of possible points of inquiry, but an exhaustive

evaluation of all medieval referents and medievalist topi within the miniseries exceeds the

boundaries of this project. Thus, the following discussion focuses on

(de)construction of the three religious icons prominently positioned within the narrative of The

Pillars of the Earth: the cathedral itself and the economics surrounding cathedral building, the

role of saintly relics within the cathedral community, and the divergent characterization of the

clergy through their sartorial representations. These elements play important roles in the closed

narrative of the miniseries because they work to bring the programstory to a definitive

conclusion by functioning specifically a kernel scenes within the narrative. Each iconic-

representation-as-kernel-scene directly affects, or at least as the potential to affect, the broader

narrative. Furthermore, as the following discussion will demonstrate, these iconic representations

allow The Pillars of the Earth to tear down its own constructions of monolithic medieval piety

and questions distribution of power, spiritual practice, and sincerity of belief within present-day

religion.

28

CATHEDRALS, SAINTLY RELICS, AND CLERICAL COSTUMING: THE

(DE)CONSTRUCTION OF ICONIC REPRESENTATIONS OF MEDIVAL PIETY

The (de)construction of The Pillars of the Earth

pietythe cathedralappropriately centers on its literal construction. The material development

of Kingsbridge Cathedral drives much of the narrative, providing both the backdrop for many

scenes and the motivation for many of the characters. Even though it may be tempting to label

these construction scenes as satellites because they appear to function as setting, in reality their

importance to the narrative

secures them as kernel scenes. Thus, the scene functionality directly influences both the

medieval cathedral as superficially static in its meaning and

its attempts to reclaim the cathedral as a site of social conflict. But how does such

(de)construction actually work within the miniseries?

Once again, the narrative operationalizes the literal construction of the Kingsbridge

Cathedral in order to question distributions of power within the church community. First, The

Pillars of the Earth uses the iconic representations of the cathedral as a literal monolith to

suggest its symbolism of orthodox medieval piety that the narrative later works to undermine.

Specifically, The Pillars of the Earth presents the fictional Kingsbridge Cathedral as

architecturally reminiscent of Salisbury Cathedral and Wells Cathedral, two of

famous great churches (see Figs. 1 and 2).

28

Importantly, Kingsbridge Cathedral architectural

reference to Salisbury and Wells reads as an attempt to historicize the fictional construction

because the miniseries sets its church building during the same period that witnessed the

overhaul of the both real cathedrals. The iconic representation of such architectural similarity

28

structure with larger windows. Like the architecture of the Salisbury Cathedral, such a construction would have

The Pillars of the

Earth

29

serves to legitimize the other historical details of the narrative like the advent of gargoyles,

flying buttresses, and stained glass windows wrapped up within the narrative.

29

By locating the

architectural facet of The Pillars of the Earth within real historical developments and authentic

medieval cathedrals, these medievalist representations align the fiction of the narrative with the

Just as one could go see Wells Cathedral or Salisbury Cathedral

today, The Pillars of the Earth seems to suggest that Kingsbridge Cathedral, if it were real,

would also remain standing as a testament of the structures durability and the lasting influence

of the Church.

Figures 1 and 2: Opening Credits for The Pillars of the Earth and Wells Cathedral, Somerset, England. A

comparison between the opening credits of The Pillars of the Earth featuring the fictional Kingsbridge Cathedral

and Wells Cathedral reveals striking architectural similarities. Also, note the emphasis the credit-looking

perspective places on the magnitude of the Kingsbridge Cathedral.

In addition to the architectural references linking Kingsbridge to real cathedrals, the

frequent low camera angles used to depict the Kingsbridge Cathedral

, just as an observer of a real

cathedral would experience (see Fig. 1). These visual cues tap into the notion of cathedral-as-

29

The Pillars of the Earth does reimagine architectural hist

perhaps the two most prominent elements of Gothic cathedrals: the flying buttress and the gargoyle. Even though

this obvious falsification of history may remind viewers that the miniseries they are watch is fictional, it nonetheless

incorporates important developments in cathedral architecture during the Middle Ages. Toward the end of the

miniseries, Kingsbridge Cathedral also displays stained glass windows.

30

-day observer, the medieval cathedral

stands as a testament to perdurability. Not only do many of these structures provide Europe with

a physical reminder of its medieval past but they also stand as monuments of the medieval

architectural histori

restful view, disclosing the structure of the whole. On the contrary, it compels the spectator to be

constantly changing his viewpoint and permits him to gain a picture of the whole only through

the entire cathedral at once reveals how the cathedral can function

as an icon of monolithic medieval piety. Because cathedrals are so physically impressive, they

loom largely in the popular imagination as symbols of the unified authority of the Church that

cannot be overcome. By referencing the symbolic physicality and the lasting historical impact of

cathedrals, The Pillars of the Earth constructs the iconic cathedral as representative of a unified,

authoritarian medieval church that the rest of the narrative attempts to deconstruct.

The deconstruction of medieval church authority, like its symbolic construction, hinges

upon the building of the Kingsbridge Cathedral. Importantly, the fictional cathedral remains

unfinished until the end of the narrative, suggesting that it has yet to become an iconic symbol of

the authoritarian church. Essentially, by emphasizing the unfinished nature of the cathedral, the

narrative provides a liminal space in which it can disrupt the notion that all cathedrals stand as

monuments to some long-entrenched religious institution. Obviously, cathedrals have long

represented a variety of things to diverse communities of people beyond the power of the Church

prowess (or excess). According to historian Christopher Brooke, the majority of cathedral

31

twin symbols of Norman domination [were the] castle and cathedral; the castle to reveal the

the Norman conquest, the (re)construction of cathedrals not only represented glorifying God but

also was a constant reminder of who was in power and who contr

strings.

32

demonstrates that, contrary to the master narrative The Pillars of the

Earth constructs, the medieval cathedral building boom was more complex than just the Church

flexing its muscles.

The cathedral of Kingsbridge too evokes more complexity in The Pillars of the Earth

than the monolithic notion of Church authority the miniseries constructs through its visual

architectural references.

33

The ebbs and flows in the construction of the Kingsbridge cathedral

due to political intrusions of the civil war unite all of the different narrative threads and

effectively reinforce the notion that cathedral construction was a long and sometimes erratic

process. Most notably,

of an all-powerful medieval church because the narrative repeatedly develops scenes during

which the laity band together against stereotypical corrupt clergyman (Waleran) or evil nobility

(the Hamlieghs) to keep construction on the cathedral going.

34

The obstacles that stand in the

provide narrative interest, but more importantly, they allow

the resultant (successful) community involvement to deconstruct the notion of Church authority

32

This notion of cathedrals representing secular power sanctified by God takes on further significance during the

reign of Henry VIII, for in establishing the Church of England, he authorized the defacing and (in some cases)

destruction of a number of cathedrals across England.

33

-as-medievalism metaphor I

discussed in the introduction. Like the castle, cathedrals too represent the ways that culture augments the medieval

past often by significantly changing it or covering it up.

34

corrupt and self-serving. At first, he wants to keep Kingsbridge from being rebuilt so as to keep funds for a new

palace for his bishopric, but his personal vendettas against several characters involved in the construction of the

cathedral eventually becomes the sole reason for interloping.

32

by suggesting that cathedral construction was a (proto) grassroots movement that developed from

some community desire for a cathedral rather than from top-down clerical command. For

example, in episode 4, the townspeople of Kingsbridge and neighboring Shiring band together

because King Stephen is planning a visit, and based on the progress, he will decide whether to

give the priory access to the local quarry for the stones they will need to keep building. Hundreds

of people arrive at the construction site to make it look like the building is coming along faster

than anticipated. In another example from episode 7, the townspeople work together to construct

a wall to keep invading noblemen from attacking their market at the behest of Bishop Waleran.

The profits from the market feed the continual construction of the cathedral, so Waleran

figures a fire will halt construction. Instead, the townspeople repel the noblemen, allowing the

market to continue.

Even though modern audiences might find such solidarity to be quaint or fantastical and

certainly inspired by economic or security issues, historical evidence suggests that lay people

were occasionally and spontaneously inspired to arduous divine labor. In a letter dating from

1145, Haimon, the abbot of St. Pierre-sur-

movement of lay people hauling stones from the quarries of Bercheres--

site of Chartres

people where inspired to work by their extreme piety, or as in the case of The Pillars of the

Earth, lured by the promise of indulgences and monies from the market, stories like Haim

remind present-day observers that the cathedrals still standing today were not only built by the

laity but also desired by them. By using the cathedral as an iconic medievalist representation,

The Pillars of the Earth (de)constructs the notion of monolithic Church authority in the Middle

Ages. Somewhat ironically, this (de)construction connects The Pillars of the Earth more closely

33

with the actuality of the diverse distribution of power within medieval religious communities as

er above testifies, although most audiences might not recognize this connection.

Instead, present-day audiences might read the emphasis on community in opposition to clerical

divisions of authority as reclamation of the Middle Ages for post-Reformation, post-

Renaissance, post-Revolution religious democracy.

Like the complex iconic representations of the cathedral that position the Church against

the community, the ambiguous position of the saintly relic within the popular imagination makes

it another prominent element of medieval piety that The Pillars of the Earth attempts to

(de)construct during the course of the narrative to suit its presentist ideological negotiations.

Within the medievalist context, few other medieval religious icons evoke such a mixed response

for current-day observers as the saintly relic. As John Shinners, a scholar of medieval popular

piety, astutely reasons,

nature, wavers between the poles of doubt and certainty. But popular belief craves certainty. It

Perhaps because relics are so

often related to miracles allegedly performed by touching or simply being in the presence of the

body parts of saints, a long history of skepticism surrounds Even though he

writes in a medieval world saturated with relic worship, Guibert of Nogent describes in 1125

worship of God and border on idol worship (Whalen 95). Nonetheless, relics remained an

important component of medieval Christianity especially for both pilgrims seeking a greater

spiritual connection (among other things) as well as cathedrals and churches whose reliquaries

provided a source of income.

36

If the position of the relic in Middle Ages was ambiguous, why

36

y Cathedral provides a contemporary example regarding

both the habits of pilgrims and the revenue they could bring into a church like Kingsbridge. Because feast days were

34

does this icon continue to be represented in medievalist production as a site of uniform

superstitious belief? By once again (de)constructing the iconic representations of the relic and its

worshippers, The Pillars of the Earth reinforces the ambiguous role of the relic through visual

and narrative cues. In this case, the relicthe physical embodiment of miracle and belief in what

cannot be seenserves as a stand-in for questions about spiritual belief in general. Unlike the

ideologies behind the (de)construction of the cathedral, the ideologies behind the

(de)construction of the relic within the miniseries narrative are less pointed in their ambivalence

and ambiguous treatment.

The relics featured in The Pillars of the Earth

but relative medieval belief in them. In true iconic representational form, both relicsthe skull

of St. Adolphus and the weeping statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary (see Fig. 3)demonstrate a

visual authenticity that immediately recalls for the present-day viewer the popular notion that

medieval piety was universally superstitious because they are featured prominently within kernel

scenes. Both are respectively positioned on the altar for all worshippers to revere. These relic

scenes construct what medieval studies scholar Steven Justice describes as

Catholic medievalism

building) and the narrative of the miniseries

miraculous that cannot be quantified by present-day people (9). These relics may represent the

relics popular during the Middle Ages, but they do not accurately portray them. Instead, the

representations of the skull and the statue transform the relic as medieval icon into a

paradigmatic medievalist representation because it exaggerates

a particular draw for pilgrims, the feast celebrating the martyrdom of Thomas Becket was actually moved from its

original date of December 29 to July 7 in hopes that better weather would draw more pilgrims; this move was so

successful that Canterbury authorities sought indulgences from the pope every fifty years to keep pilgrims coming

back to worship (Webb 66). Although this current discussion focuses on medieval relics and pilgrimages, many

cathedrals continue to draw pilgrims with their relics. Chartes, Salisbury, Canterbury and Santiago de Compostela

are just a few sites of medieval pilgrimage that continue to remain popular destinations today.

35

position within medieval piety.

37

Furthermore, the medievalist representations of these relics

extend into the narrative structure of the miniseries. Each relic plays an important role in the

-performing medieval relics.

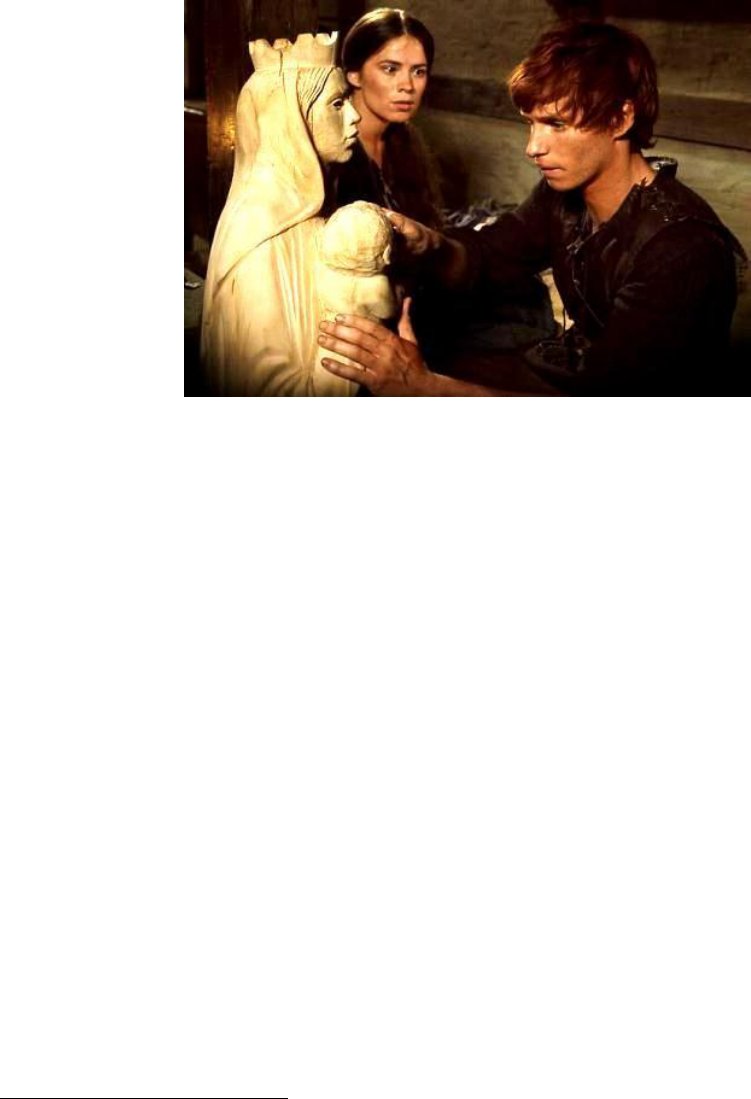

Figure 3: Weeping Statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary from The Pillars of the Earth. Jack Jackson (Eddie

Kingsbridge Cathedral in hopes that it will bring pilgrims and their money to town.

During the first fire that destroyed the original Kingsbridge Cathedral, Prior Philip is

unable to rescue the skull of St. Adolphus; yet, because the relic means so much to the priory in

economic terms because it draws pilgrims, he secretly replaces the destroyed skull with another

skull (presumably from a deceased monk at the priory). This action, which representatively

reflects a popular strain of thought regarding relicsthat is, that they are not miraculous, and

therefore no one will know if also provides

one of the monks with information to blackmail Prior Philip out of his position as prior.

37

36

authenticity of relics.

44

Once the , Kingsbridge Cathedral

has no reliquary with which to attract pilgrims and their money because they decide it is better to

be poor than to be dishonest.

The

Pillars of the Earth, the role of the relic in

medieval piety is emphasized through unusual size yet at the same time the

motivations of relic worship (and ownership) are called into question .

Audiences might assume that Prior Phillip acts out of good intentions when he replaces the skull

because the narrative depicts him in all other scenes as an honest and trustworthy man, but he

ultimately replaces the skull so that the priory can continue to profit from the pilgrims attracted

by the relic. Although these scenes do leave space for a moral messagethe monks do decide to

reject the inauthentic relicthey nonetheless cast the familiar skeptical shadow onto the position

of relics within medieval piety.

The Pillars of the Earth’s second, perhaps more dubious relic builds on top of the

present-day skepticism established by the St. Adolphus skull storyline. After being exiled to

France for fathering a child out of marriage (and while a novice monk!), Jack Jackson seeks out

work as a stonemason at Chartes Cathedral. After encountering a strange stone that will produce

condensation once the sun sets, Jack comes up with the idea to create a statue of the Virgin Mary

act pilgrims.

Indeed, this is an effective strategy, at when viewed in light of the history of Marian

iconography, because, by the twelfth century, the cult of Mary universal saint,took away

44

The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200-1336 discusses this

pervasive notion in much detail.

37

from the importance of corporeal remains of local

saints were revered well into the later Middle Ages, this period marks a significant shift in the

saintly cults, during which the Virgin Mary became the preeminent, universally-known saint.

45

While the audience watches, Jack creates this statue. Clearly, it is not a relic in the traditional

sense, and, because of the economic imperative that encouraged its creation, one doubts that

The type of iconography implied in this scene, surprisingly or not, calls to mind Christian

doctrine about pagan worship alluded to in Second Nun’s Tale, in which the devout

Cecilia refuses to worship manmade

(lines 284-7).

saintly relics, because they are made by God, are living entities. Manmade

idols in the eyes of Christians therefore

lack the innate living spirit that only God can provide. As the sun slowly sets on the cathedral

praying because the statue appears to be living.

46

Even Jack, the creator of the statue appears

moved by the miraclemanmade or divinethat brought the pilgrims back to Kingsbridge.

whether a real miracle has actually transpired and reminds viewers of the important role that

relics played in medieval piety. This (de)construction of the relic as a uniform medieval icon

questions the belief in the miraculous through the destruction of St. Adolphuslso

suggests that belief in somethingeven a manmade statuecan result in palpable miracles.

45

This marks another connection between Salisbury Cathedral and Kingsbridge; Salisbury is known conventionally

as The Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary locally.

46

In another sense, the parishioners are literally worshipping a rock. This recalls the Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale when a

greedy priest falsely worships stones he believes an alchemist can turn into gold.

38

Like the (de)constructions of the cathedral and the relic that tap into popular

misconceptions about medieval piety in order to inject heterodoxy into the supposed monolithic

master narrative of western Christianity, the iconic representations of clerical morality via

sartorial characterizations also figure prominently in The Pillars of the Earths ideological

interrogations of spiritual sincerity. In particular, the miniseries pits its two iconic clergymen

scheming careerist Waleran and earnest pragmatist Phillipagainst one another in order

deconstruct the popular misconception that all medieval clergy were corrupt. Moreover, the

iconic representations of clerical vestments as indicators of piety

iconic representations in the miniseries because they directly recall the sartorial probing

operationalized by the Investiture Controversy and the Estate Satire genre epitomized by

ChaucerCanterbury Tales. The of Waleran and Phillip not only marks the

narratives progression toward closure but also suggests that a more complex reading of clerical