21*$/,(3$/0(1521*$/,(3$/0(15

(&(1 *-++-,021*$/,(3$/0(15(&(1 *-++-,021*$/,(3$/0(15

/ #2 1$'$0(0-**$"1(-, / #2 1$"'-* /0'(.

0005$*(&(-,5,"/$1(".(/(12 *(15 ,# 3(& 1(,&1'$ 0005$*(&(-,5,"/$1(".(/(12 *(15 ,# 3(& 1(,&1'$

-1$,1( *%-/(0 ../-./( 1(-,+-,& /1("(. ,10(,*$"1/-,("-1$,1( *%-/(0 ../-./( 1(-,+-,& /1("(. ,10(,*$"1/-,("

,"$20("2*12/$ ,"$20("2*12/$

,($* ")70''(1$

21*$/,(3$/0(15

-**-41'(0 ,# ##(1(-, *4-/)0 1'11.0#(&(1 *"-++-,0!21*$/$#2&/1'$0$0

/1-%1'$20("-*-&5-++-,0

$"-++$,#$#(1 1(-,$"-++$,#$#(1 1(-,

")70''(1$ ,($* 0005$*(&(-,5,"/$1(".(/(12 *(15 ,# 3(& 1(,&1'$-1$,1( *%-/

(0 ../-./( 1(-,+-,& /1("(. ,10(,*$"1/-,(" ,"$20("2*12/$

/ #2 1$'$0(0

-**$"1(-,

'11.0#(&(1 *"-++-,0!21*$/$#2&/1'$0$0

'(0'$0(0(0!/-2&'11-5-2%-/%/$$ ,#-.$, ""$00!51'$/ #2 1$"'-* /0'(. 1(&(1 *-++-,021*$/

,(3$/0(151' 0!$$, ""$.1$#%-/(,"*20(-,(,/ #2 1$'$0(0-**$"1(-,!5 , 21'-/(6$# #+(,(01/ 1-/-%

(&(1 *-++-,021*$/,(3$/0(15-/+-/$(,%-/+ 1(-,.*$ 0$"-,1 "1#(&(1 *0"'-* /0'(.!21*$/$#2

Bass Is My Religion: Syncretic Spirituality and Navigating the Potential for

Misappropriation Among Participants in Electronic Dance Music Culture

by

Daniel Backfish-White

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the

Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Musicology

in the School of Music, Jordan College of the Arts of Butler University

Thesis Defense: Thursday, April 22, 2021 at 1 p.m.

Committee:

Clare Carrasco, Chair and Advisor _____________________________________

Nicholas Johnson, Reader ____________________________________________

Rusty Jones, Reader _________________________________________________

Date of Final Thesis Approval:_______________________ Advisor:_______________________________

4/30/2021

5/4/2021

5/5/2021

5/4/2021

Table of Contents

Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ i

Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... ii

Chapter 1: Introduction and Literature Review .............................................................................. 1

Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 4

Constructing a Syncretic Spirituality .......................................................................................... 6

Literature Review...................................................................................................................... 17

Overview ................................................................................................................................... 27

Chapter 2: Psychedelic Downtempo: Desert Dwellers ................................................................. 29

“Saraswati’s Twerkaba” and Sound Sources ............................................................................ 31

Intentional Festivals .................................................................................................................. 38

Chapter 3: TroyBoi ....................................................................................................................... 47

“Mantra” and TroyBoi’s Musical Representations ................................................................... 48

TroyBoi at Live Events in the United States ............................................................................ 52

Chapter 4: Cult DJs, Bassnectar.................................................................................................... 58

Bassnectar’s Musical and Visual Aesthetic .............................................................................. 59

The Bassnectar Community ...................................................................................................... 61

Bassnectar’s Personal Life and Subsequent Downfall.............................................................. 66

Chapter 5: Conclusion................................................................................................................... 71

Bibliography ................................................................................................................................. 74

i

Abstract

At electronic dance music events in the United States, artists and attendees tend to appropriate

religious and spiritual sounds, images, and dress, especially from India but also from elsewhere,

to varying degrees. This project explicates the effects of adopting religious symbology, ethos,

and atmosphere in the music and culture of EDM, specifically in bass music culture. It argues

that although individual participants may adopt aspects of religious traditions in ways they

perceive as authentic, the potential for misappropriation still exists. In other words, EDM culture

creates opportunities for misappropriation that individual participants navigate in order to

construct their own individual forms of spirituality in relation to the live music experience and

EDM culture at large.

Utilizing a set of seven interviews with individuals who have close ties to the EDM community,

this project explores the ways that attendees navigate conversations about cultural appropriation,

specifically in the bass music community. A set of common attitudes, opinions, and beliefs

forges a syncretic spirituality among these seven interviewees, which inform how these

individuals navigate conversations about appropriation in the EDM community. In addition to

these seven interviews, three case studies that focus on specific artists who spearhead specific

subscenes frame this project: the psychedelic downtempo duo Desert Dwellers, the multiethnic

trap artist TroyBoi, and the cult dubstep DJ Bassnectar. Synthesizing ideas by these seven

interviews with previous EDM scholarship and specific cases within these communities, I

conclude that as artists and attendees negotiate meanings with one another, they must ultimately

choose to justify their appropriation, often by claiming a syncretic sense of spirituality, or to

avoid association with it entirely.

ii

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I would like to thank the two scholars that form the Butler Music

History department, Dr. Nicholas Johnson and Dr. Clare Carrasco. Without their passion and

talent which together make talking about music fun, I would not have begun this musicology

program. Special thanks to Dr. Carrasco, who served as my thesis advisor, and whose graduate

seminars directly inspired this project.

Second, I would thank the seven interviewees, many of whom are dear friends. Their

thoughts directly contributed to the ideas that frame this project.

Third, I would like to thank my partner, Kevin Backfish-White, who served as my

ideological punching bag. Thank you for listening to all of my rants and tangents, which often

led to “aha” moments.

Fourth, I would like to thank my parents, Nancy and Timothy White, who fostered my

musical journey from a young age, and who endlessly support my scholarly escapades.

Lastly, thank you to the entire EDM community, artists and audience members alike. I

will see you all on the dancefloor!

1

Chapter 1

Introduction and Literature Review

Electronic dance music (EDM) events in the United States host artists who produce and

DJ in a plethora of styles such as house, techno, dubstep, and downtempo. Many disparate

traditions influence the sounds and stylings of each genre. One of the more omnipresent

influences across multiple EDM cultures is the sounds, imagery, and philosophy of India and

Hinduism as represented in sound samplings (both musical sounds and spoken word), visual

projection at live concerts, costuming and vending at music festivals, and workshops and

ceremonies hosted by these festivals. Buddhist, neo-pagan, and other mystic and religious

traditions from around the world are also influential, creating a highly syncretic sense of

spirituality that is projected both aurally and visually at live performances and festivals.

Attendees of these events also tend to appropriate—or perhaps misappropriate—these cultures to

varying degrees through their dress and/or professed attitudes, opinions, and spiritual beliefs.

Though these types of samplings and appropriations occur across many popular music genres,

especially hip-hop, for the purposes of this project, my primary focus will be on EDM.

For this project, I define appropriation based on Bruce Ziff and Pratima V. Rao’s

explication of the concept.

1

As these authors and many others have noted, the concept of cultural

appropriation is difficult to define and often nebulous in its application. In addition,

conversations about cultural appropriation frequently take place on social media and other

1

. Bruce Ziff and Pratima V. Rao, “Introduction to Cultural Appropriation: A Framework for Analysis,” in

Borrowed Power: Essays on Cultural Appropriation, eds. Bruce Ziff and Pratima V. Rao (New Brunswick: Rutgers

University Press, 1997), 1–27.

2

widely accessible forums, influencing its definition and cultural significance.

2

In essence,

appropriation may occur when members of one culture borrow elements from another culture.

Such borrowing may be problematic and thus might better be termed misappropriation when

members of a dominant culture, such as mostly white, economically privileged EDM festival

attendees in the United States, take from marginalized minority cultures. As Ziff and Rao have

noted, this appropriation can harm the marginalized communities, whether by creating false or

caricaturized stereotypes of that culture, or by rendering the culture as somehow primitive or

“less than” the dominant culture. Appropriation can also impact the cultural object itself, as the

act of appropriation may “damage or transform a given cultural good or practice.”

3

Cultural

appropriation may also allow the dominant culture to benefit materially or financially to the

detriment of the original creators. In many cases, “law fails to reflect alternative conceptions of

what should be treated as property or ownership in cultural goods,” such that there are few legal

protections regarding issues of cultural appropriation.

4

This may lead marginalized peoples to

feel cheated when these borrowers do not obtain prior consent.

This project seeks to explicate the effects of adopting religious symbology, ethos, and

atmosphere in the music and culture of EDM, specifically in bass music culture, here defined as

any EDM genre with a focus on the live experience and a focus on the high amplification of bass

frequencies. Though in certain instances these borrowings may lead to intentional communities,

alternative political viewpoints that challenge the status quo, and an increased sense of belonging

in a spiritual sense, EDM culture may misrepresent the cultures from which it borrows and in

2

. Maria Fang and Shaun Axani, “What’s Up with Cultural Appropriation on Social Media?” published January 3,

2016, Medium, https://medium.com/@mariafang/what-s-up-with-cultural-appropriation-on-social-media-

be43211c91a7.

3

. Ziff and Rao, “Introduction to Cultural Appropriation,” 8.

4

. Ziff and Rao, “Introduction to Cultural Appropriation,” 8–9.

3

turn foster negative or false stereotypes. There may also be a monetary imbalance of power

between the borrowing (dominant) culture and the cultures from which it borrows.

In addition to these negative drawbacks of appropriation, artists’ inflated egos can

contribute to god complexes that lead to abuse of power and privilege, as in the case of the

American dubstep producer Bassnectar. As Bassnectar presented himself as a spiritually evolved

figure in the EDM community, he was deified by fans. This deification perhaps contributed to

his manipulation of young women, as he was accused in 2019 of engaging in sexual acts with

several minors. Thus, the deification of artists, especially those that present themselves as

spiritually superior, could contribute to their abuse of power, as others have noted.

5

I argue that although individual participants may adopt aspects of religious traditions in

ways they perceive as authentic, the potential for appropriation still exists. In this way, this

project seeks to insert itself into a larger conversation regarding cultural appropriation in the

EDM community by situating itself between two bodies of scholarship: one that praises EDM’s

positive qualities without acknowledging its potential for misappropriation, and another that

condemns EDM festival goers as culturally appropriative without acknowledging the positive

aspects of its spiritual associations. Through critical analysis of songs and videos by select EDM

artists, my own experience attending many live EDM concerts and festivals, and interviews with

a careful selection of artists and frequent festival goers, I show that EDM culture creates

opportunities for misappropriation that individual participants navigate in order to construct their

own individual forms of spirituality in relation to the live music experience and EDM culture at

large. In three case studies focusing on specific electronic dance music producers—Desert

Dwellers, TroyBoi, and Bassnectar—I consider the varied ways in which artists and attendees

5

. Rupert Till, “We Could Be Heroes: Personality Cults of the Sacred Popular,” in Pop Cult: Religion and Popular

Music (London, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010), 46–73.

4

negotiate meanings with one another. In doing so, they create feedback loops of influence that

ultimately forge a highly syncretic yet insular brand of spirituality. When participants claim

“bass music is my religion,” they open space for a complex conversation about the role of

appropriation in the construct of this spirituality.

Methodology

The seven interviews for this project were conducted in the winter of 2021, and all took

place via the video call platform Zoom. Due to the often sensitive nature of discussing ideas

about appropriation in today’s sociopolitical climate, the interviewees were chosen based on

their familiarity to the researcher and their close relationship to the EDM scene. They will be

referred to by pseudonyms throughout:

Amanda: The first interviewee is a twenty-six-year-old Vietnamese American female living in

Indianapolis who has only been listening to EDM for two years but has formed a close

relationship with the type of syncretic spirituality discussed in this project.

Beth: The second interviewee is a twenty-eight-year-old white female who has been listening to

EDM for over twelve years. She has been to over one hundred festivals and concerts, worked as

a marketing manager for the biggest nightclub in Denver for three years, and helped to run an

EDM blog for three years. During her time as a journalist, she interviewed artists and travelled to

many festivals in both the EDM and jam band circuit.

5

Carl: The third interviewee is a thirty-one-year-old white male who has been listening to EDM

for over twelve years and who has also been to over one hundred festivals and concerts. He is a

singer-songwriter who incorporates elements of EDM into his projects and also creates amateur

EDM tracks as a hobby. Carl has helped to lead workshops at various festivals in both Indiana

and California, where he currently resides in Santa Cruz. In addition to his musical expertise,

Carl has also participated in ayahuasca ceremonies with a grassroots organization in California.

Dan: The fourth interview is a twenty-six-year-old white male who has been working as an

EDM artist since 2012. Dan is a DJ in various capacities and also produces his own music, which

he frequently DJs in his hometown of Indianapolis. Dan has also led sound-healing sessions that

infuse electronically produced frequencies with meditation.

Evan: The fifth interviewee is a thirty-seven-year-old white and Native American male who has

been listening to EDM for almost twenty years. He currently lives in Indianapolis where he

practices psychotherapy primarily with children who have high degrees of trauma. In addition to

this work, Evan conducts formal research on psychedelics in therapeutic settings with a team of

psychotherapists.

Fiona: The sixth interviewee is a thirty-year-old biracial female (black and Caucasian) who has

been listening to EDM and attending concerts and festivals for over fifteen years. Fiona works as

a social worker with the homeless population in Indianapolis.

6

Garrett: The last interviewee is a thirty-year-old Indian American male who has been listening

to EDM music for twelve years. He currently resides in Chicago, where he works as a

psychologist.

The seven interviewees were carefully selected to prioritize depth within each interview

rather than breadth of interviewees: there are only seven total interviews, but each lasted

approximately two hours. I believe this approach is favorable to this project, as discussions about

cultural appropriation are bolstered by a familiarity between researcher and interviewee.

Individuals are more likely to be open, honest, and comfortable when speaking about cultural

appropriation with someone familiar to them. In addition to these seven perspectives is my own,

that of a thirty-one-year-old white male living in Indianapolis who has attended over thirty EDM

music festivals as well as numerous concerts and who also considers himself spiritual. Though

the interviews represent only seven people within the EDM scene—and they do not always agree

on issues of cultural appropriation—I believe that many of the attitudes and opinions expressed

by the interviewees are common among a specific set of participants within the EDM scene,

especially those who have fostered what I will call a syncretic sense of spirituality through their

participation in EDM culture.

Constructing a Syncretic Spirituality

To understand the syncretic spirituality referenced throughout this project, it must be

clearly defined. The term “spirituality” is ambiguous—it is considered here as a product of EDM

culture, and indeed the seven interviewees help to define its meaning. For many EDM attendees,

it is constructed from a variety of sources, but most prominently Eastern religious thought

7

(especially Buddhism), New Age philosophy (Eckhart Tolle, for example),

6

and psychedelic

philosophy (such as Terrence McKenna).

7

In addition to syncretism of these pre-established

religious or philosophical ideologies, direct psychedelic experience informs a great deal of

individual spirituality. In interviews for this project, interviewees’ comments centered on eight of

what I call “tenets” that aid in the construction of a recognizable syncretic spirituality for EDM

attendees, as summarized in Table 1 and described below.

Table 1. Eight Tenets of a Syncretic Spirituality

1. General distaste for organized religion

2. “Interconnectivity”

3. EDM as community

4. EDM as therapy

5. The mundane as spiritually informed

6. America as lacking community or spirituality

7. Aestheticization of spiritual technologies

8. The inevitability of spiritual experience at live EDM

events

First, EDM attendees express a general distaste for organized religion. In the United

States, this often means turning away from a traditional Christian upbringing. Dan’s anecdote

expresses a common attitude among many EDM attendees:

I was raised Christian, but when I was thirteen, I started wondering if all these people that

are telling me how it is really knew, or if they were all just as confused and lost as I was.

And I found out very quickly that that was the case, and I stopped paying attention to

6

. Eckhart Tolle is the author of popular mindfulness books such as The Power of Now and A New Earth:

Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose. One of the central tenants of the latter is that by making personal changes in your

own life that embrace a mindful lifestyle, others will follow suite, and this “flowering of consciousness” will create

a “new earth” in which everyone is seen to have awakened to their life’s purpose. Eckhart Tolle, The Power of Now:

A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment (Novato, CA: New World Library,1999); Eckhart Tolle, A New Earth:

Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose (New York: Penguin Books, 2005).

7

. Terrence McKenna is a popular ethnobotanist, speaker, and writer of many books who advocated for responsible

psychedelic drug use. His “Stoned Ape Theory” also popularized the idea that man may have evolved and thereby

tripled their brain-size after a group of proto-humans consumed magic mushrooms in the wild. Terrence McKenna,

Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge, A Radical History of Plants, Drugs, and Human

Evolution (New York: Bantam Books, 1993).

8

what the man at the pulpit said, because he didn’t know what the hell he was talking

about either. There’s been problems with certain Christians in my experience of it, and

it’s kind of made me not want to go to church on Sunday.

8

Dan expresses his sense of disenfranchisement from Christianity via his distrust for his church’s

leadership, which began in adolescence. He is careful, however, to delineate “certain Christians,”

showing that his distancing does not equate to total dismissal. Indeed, he continues: “There’s still

parts of [Christianity] that I do follow. One rule that everyone could probably follow is the

golden rule: treat others like you would want to be treated. That follows along PLUR [Peace,

Love, Unity, Respect], so everybody who abides by PLUR is kind of following one aspect of the

Bible. Even if they hate Christianity.”

9

Though the golden rule is found in many theologies

throughout the world, Dan’s comments show his openness to adopting aspects of Christianity

that fit into his personal construction of spirituality.

Carl also explains that disenfranchisement from traditional religion leads EDM attendees

to seek alternative spiritual expression: “I think that’s something that draws people to those

religious sub-cultural expressions too is that they get wounded by the dominator culture. They’re

looking for alternative ways to give meaning to their life.”

10

EDM attendees often turn to Eastern

religious thought, which informs their spiritual beliefs with varying intensities. Beth echoes this

shift from her traditional Christian upbringing to aspects of Eastern religious practices, which she

found through attending music events:

I’m not really religious, but I grew up in Indiana going to Christian church. I don’t follow

any of those beliefs. I would say now, through music and festivals, I’ve been connected

with more spiritual beliefs. I’m very into meditation and yoga and those internal

practices. I wouldn’t say I follow a religion, but I definitely follow practices of other

religions like Buddhism and stuff. I definitely discovered that from festivals and that

world, meeting people that have influenced me with those kinds of beliefs too.

11

8

. Dan [pseud.], interview via Zoom by Daniel Backfish-White, January 28, 2021.

9

. Dan [pseud.], interview. PLUR is a common saying among ravers since the 90s.

10

. Carl [pseud.], interview via Zoom by Daniel Backfish-White, January 22, 2021.

11

. Beth [pseud.], interview viz Zoom by Daniel Backfish-White, January 26h, 2021.

9

This common trajectory—turning away from a traditional religious upbringing, discovering

spirituality, turning to some sort of mindfulness practice inspired by Eastern religions, and

exploring this spirituality through live music—was expressed in some fashion by all seven

interviewees.

A second cluster of comments involve ideas about “interconnectivity,” a concept that is

difficult to define. At its core, it is the idea that all matter is inherently connected by energy, and

therefore all living beings are interconnected. Its meaning is often esoteric and individually

constructed, and for many EDM attendees, it has close ties to a specific psychedelic experience,

as the consumption of drugs is commonplace and fairly ubiquitous among EDM attendees. It is a

concept often related to an esoteric idea of “oneness.” Evan states:

I feel like for the longest time I pushed away spirituality in part because I didn’t even feel

connected to myself. Largely through [psychedelic] mushrooms, I found spirituality in

the sensations of interconnectivity and that helped to catalyze my search. Over the years,

I’ve formed my own little spirituality that borrows heavily from Eastern philosophy, but

also Native American philosophy, some Judeo-Christian stuff. Pretty much, if it resonates

with me, then I try to adopt principles that can help better my life.

12

Here, Evan describes interconnectivity as a fleeting sensation and relates it to the idea of

spirituality as a form of therapy. Evan later comments on this idea of interconnectivity in relation

to what is not included in his brand of spirituality: “By recognizing that we’re not isolated,

recognizing that Western ideology is not the end-all be-all, and learning to take what works well

from that, filter out religious dogma, and use it in a way that best serves oneself.”

13

This

succinctly captures his turn away from traditional religious practice (Christianity in the United

States), which he views negatively as dogmatic, his turn toward spiritual practices that help him

to remember that humans are interconnected, and his drive to become a morally, emotionally,

12

. Evan [pseud.], interview via Zoom by Daniel Backfish-White, February 2, 2021.

13

. Evan [pseud.], interview.

10

and spiritually healthy individual. Dan likewise professes, “I believe that all of our spirits are

connected in some way. When you experience something about another spirit, you’re learning

something about yourself in some way. We’re all one in some way.”

14

For other interviewees,

this sense of connection plays out on multiple levels. For Garret, “it is this kind of abstract thing,

connection, whether it’s connection to yourself, to your mind, to your body, or something greater

like nature or something outside of us.”

15

This type of connection provides Garrett a sense of

peace that he considers the overarching goal of spirituality. For Garett personally, there is also a

degree of relativism to this idea: “[Spirituality] is the same thing as religion, just stripped of

tradition, right? When I think about Christianity…it’s a framework. I think the same is true for

Hinduism…When we talk about spirituality, you’re stripping it of that tradition, the way of doing

it, that way of approaching it, but you’re still keeping the principles.”

16

For Garrett and perhaps

many EDM attendees, there are many paths to the same sense of connection—participating in

EDM culture to varying degrees is perhaps only one way to achieve this.

This sense of interconnectivity also extends to interpersonal relationships among festival

attendees, which foster a sense of community. Thus, a third tenet in interviews for this project

posits that the community created through authentic connection with others is part of the spiritual

experience for EDM attendees. Relating this idea to cultural borrowing, Evan says, “Seeing as

EDM borrows heavily from cultures that embrace collectivity or even tribalism, it encourages us

not only to discover ourselves, but discover our friends, discover strangers we don’t know.”

17

This openness to create a sense of community through radical self-discovery and interpersonal

connection is essential to the construction of spirituality for EDM attendees. The EDM

14

. Dan [pseud.], interview.

15

. Garrett [pseud.], interview via Zoom by Daniel Backfish-White, February 24, 2021.

16

. Garrett [pseud.], interview.

17

. Evan [pseud.], interview.

11

community is often viewed internally as one that embraces people of all genders, sexual

orientations, and races. For Beth, “You go to a show, and it’s all about inclusivity. People who

are gay and struggling to come out: that’s the kind of community that I think they would need.

I’ve felt down and depressed before and the EDM community has brought me up and made me

feel accepted.”

18

The idea of the EDM community as one that allows people to be their authentic

selves is spiritual in that it gives attendees a freedom of expression that may otherwise be absent

in their daily lives. This in turn fosters a sense of acceptance, which encourages attendees to

express themselves even further. A feedback loop is created, and in a sense, people return to

these events over and over to feel this freedom. As individuals repeatedly see each other at these

events, they form strong bonds, often holding one another accountable to be what they might

term as “their most authentic selves.” At the same time, this freedom of expression also creates

room for individuals to misappropriate—an individual may justify wearing an inappropriate

costume from another culture as an embrace of their “authentic self,” when in reality they have

little understanding of the appropriated culture.

A fourth spiritual tenet is the idea that EDM and its event culture constitute a form of

therapy. For many attendees, live EDM events are therapeutic in various ways, and this aspect

contributes to the culture’s associations with spirituality via its fostering of community. Carl

states, “When I was deeply into Papadosio, I relied on those shows and the community around

them to work through difficult emotions.”

19

For others, EDM culture offers a refuge from the

stresses of modern life. For example, Amanda says, “The most common issue in mental health is

people feeling like they have nowhere to go, no one to talk to, people putting way too much

pressure on themselves to look a certain way, sound a certain way, have a certain job, make a

18

. Beth [pseud.], interview.

19

. Carl [pseud.], interview.

12

certain amount of money, but in EDM, it truly doesn’t matter.”

20

While Amanda’s comments

gloss over the fact that individuals with more financial resources or social capital might occupy

more privileged positions in the EDM community, it nonetheless demonstrates that many

individuals see the community as supportive. For some participants, the music itself and the sub-

contextual messages it projects are therapeutic. Dan and other artists such as Earthcry often

incorporate specific frequencies in their music that have associations with either binaural beats or

sound healing traditions.

21

Music also has the capability of supporting meditation, which is a key

component of spirituality in this context. For Dan, “Music can be very meditative. Even just

beyond music: sound and vibration in general can be healing and therapeutic. Everything is

energy. Spiritual energy and sound kind of go hand in hand.”

22

Festival goers frequently mention

this concept of energy, which is also individually constructed and difficult to define in toto.

A fifth tenet of EDM spirituality concerns the idea that some spiritual components

learned from EDM events carry into daily life. This not only means that individuals incorporate

specific spiritual practices into their routines, but also that they see themselves as carrying a

sense of spirituality into every aspect of their being and livelihood. My interviewees tended to

associate this with a perceived “other” culture from which such ideas and practices are borrowed.

For Dan, “In pagan culture, everything you do… making yourself a meal and nourishing

yourself, that’s pleasing the gods because that makes you happy. It’s a holistic way of looking at

20

. Amanda [pseud.], interview via Zoom by Daniel Backfish-White, January 22, 2021.

21

. “Binaural beats can be briefly described as auditory responses originating in each hemisphere of the brain that

are caused by the interaction between two slightly detuned sine waves, divided between the left and right ears…if

one listens long enough, one’s brainwave will enter into a sympathetic resonance with this pulsing…This technique

has been shown to be useful as a tool for consciousness management in such areas as stress reduction, pain control

and the improvement of concentration and information retention…some believe that [it] may facilitate the

actualization of more esoteric practices such as astral projection, telepathy, and lucid dreaming.” David First, “The

Music of the Sphere: An Investigation into Asymptotic Harmonies, Brainwave Entrainment and the Earth as a Giant

Bell,” Leonardo Music Journal 13 (2003): 31.

22

. Dan [pseud.], interview.

13

it, because anything that makes you happy makes your gods happy.”

23

While Dan does not cite a

specific religion or culture, he nonetheless acknowledges that this holistic view of life is drawn

from elsewhere. This concept is perhaps best expressed by popular mindfulness author Thich

Nhat Hanh: “Each thought, each action in the sunlight of awareness becomes sacred. In this light,

no boundary exists between the sacred and the profane.”

24

Carl also recognizes, “In a native

culture that would have a medicine tradition, making clothes, making shelter, the way you treat

your food, and your landscape are indivisible from the religion, because they are all part and

parcel to continually lifting humanity out of that animal state where they have to figure out life

for themselves without guidance.”

25

For Carl, this idea of spirituality extending to every part of

life has associations with civilization—the development of advanced culture, language, and

technology that distinguish humans from animals.

Carl also relates this to a sixth spiritual tenet, stating “For [America’s] advanced

technologies and stuff, socially, we’re the most primitive nation to ever exist. We have no

cultural guidance…That’s why I think there’s such a deep hunger in America for transformation

and religious subcultures because there is an obvious and glaring need for this in our society.”

26

A key component that unifies many in the EDM scene is a view that contemporary American

culture is somehow void of spirituality or community, and therefore many seek an alternative

route of spiritual connection. I have already established that many EDM attendees reject

Christianity based on their upbringings or past negative experiences. These alternative pathways

include not only attending and participating in EDM event culture, but also adopting spiritual

23

. Dan [pseud.], interview.

24

. Thich Nhat Hanh, Peace is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life (New York: Bantam Books,

1991).

25

. Carl [pseud.], interview.

26

. Carl [pseud.], interview.

14

practices from other cultures to fill that spiritual void. Relating America’s lack of spirituality and

community to interconnection, Evan says,

We live in a culture where we’re pretty much devoid of ritual and rites of passage. Last I

read, getting a cell phone is now considered more of a rite of passage than getting a car. If

that’s all we have to look forward to, to define where we’re at in society is like, “Do we

have a phone and social media to feign connection?” Of course we’re running around

messed up and disconnected!

27

Evan posits that America’s lack of spiritual practices leads to substitution of these perceived

losses with hyper-modernized versions of these acts. For him, this leads to disconnection and

disenchantment, both of which lead many individuals to seek ways to break this pattern. In

addition, Evan says, “Our culture is one of this sort of rabid individualism. We are taught that we

are separate from everything, that we have to be better, and that the foundations of our modern

world with materialism naturally breaks things down into these separate parts.”

28

America’s

association with “rabid individualism” stands in direct contrast to the community mindset often

promoted by EDM event attendees and organizers. By fostering a sense of community within

and among EDM attendees, individuals see themselves as committing to a spiritual practice that

is also politically subversive to some degree.

Many of my interviewees also mentioned that objects borrowed from other cultures may

serve a particular spiritual purpose, and therefore function as shareable technologies, an idea that

constitutes a seventh tenet among interviewees. They see their adoption of some select spiritual

technologies as constituting a deep embodiment or aestheticization. For these individuals, certain

spiritual technologies have been around for eons, and they exist in many cultures in various

ways. Items such as singing bowls, the intoning of ohm, adapted versions of instruments meant

to maintain a steady beat or meditative drone during religious practices, and more are seen as

27

. Evan [pseud.], interview.

28

. Evan [pseud.], interview.

15

constituting a sense of timeless spiritual technology, almost akin to a public domain of spiritual

practice. This may, of course, become problematic when individuals from a dominant culture

perhaps misrepresent or misuse objects—especially specific objects that may be considered

sacred—from a subordinate culture. Relating a specific example to America’s lack of spirituality,

Amanda says, “When I have my pashmina at a rave, I feel like I have my best friend with me on

my shoulder, keeping me safe, warm, joining me on my adventure. We use these items from

these other cultures not because we don’t respect them but because of their beauty, and because

American culture these days doesn’t have it.”

29

Though pashminas might not have a cultural

significance that would render their borrowing problematic, her statement still exposes the fact

that misappropriation almost always happens unintentionally, revealing that EDM attendees tend

to think of their adoption of aspects of another culture as aestheticizing a deep embodiment of a

spiritual practice. In other words, the objects from another culture may serve as a framework for

transfigurations of those objects on aesthetic lines—for example, a vendor at an EDM festival

may sell an object resembling a Tibetan singing bowl but adorned with psychedelic fractal

patterns that they themselves created, rather than a Tibetan artisan. The framework for the

technology, which is used in meditation in either context, is altered to fit the aesthetic values of

the EDM community and is therefore less directly appropriated.

An eighth and final tenet gathered from interviewees is the perception of an inevitability

of spiritual experience at live EDM events. Many people who are drawn to this culture can relate

a story about their first live music experience, their “aha” moment. In these stories, interviewees

often described a moment of complete bliss, relinquish of control, and a cathartic release of

emotion. They also frequently linked this to a simultaneity of realizations, including but not

29

. Amanda [pseud.], interview.

16

limited to the various aspects of spirituality heretofore described. Speaking of the complex

development of early EDM events through to today, Carl states, “So, people go to [EDM events]

and they would have spiritual experiences. They don’t need any sort of aesthetic guidance, they

just emerge. It’s part of humanity. So then to encourage that kind of behavior, there’s kind of a

feedback loop of aestheticization.”

30

Carl here notes that in the beginning of EDM event culture

(circa the late 1980s into the early 1990s), attendees would have spiritual experiences without

any sort of outside influence; the music was enough. As EDM events gained more traction and a

mélange of DJs, performers, event promoters, light technicians, VJs,

31

and later workshop hosts,

festival vendors, and even the attendees themselves began to participate in this complex, ever-

evolving culture, they continually influenced one another to further induce these spiritual

experiences. This then leads to a highly insular brand of spirituality in the EDM community.

While EDM event culture is not monolithic and reducing all EDM events under the

umbrella “EDM culture” is not without problems, a syncretic spirituality emerges by connecting

common attitudes of disparate participants in EDM culture. The interviews I conducted revealed

that although participants may have personalized constructions of spirituality, they share

common features that can unite them in several important ways. Many of these tenets of EDM

spirituality are also described variously by scholars who write about EDM event culture. These

authors form an array of perspectives and often critique and/or voice support for EDM attendees’

adoption of spirituality.

30

. Carl [pseud.], interview.

31

. In this context, a term for “visual DJs,” who program visual projections for live shows.

17

Literature Review

Scholarship on EDM tends to fall into two broad categories. On the one hand, a

substantial body of EDM research focuses on dance culture’s ecstatic and transformative

qualities without explicitly recognizing the cultures from which is borrows. Another side of

EDM research centers on the appropriative or gentrified aspects of EDM culture. Scholars often

touch upon several common, important dimensions in their support or critique of EDM culture:

the relative spirituality of dance music events, which range from secular to overtly spiritual; the

degree to which events are politically or economically subversive, as some festivals are

sponsored by large corporations, whereas others are more grassroots; and the relative

commitment of organizers and attendees to environmental sustainability, as EDM can be sites of

profound consumption or potential sites of environmental healing. Each of these dimensions, as

well as their interaction with questions regarding racial identity, are important factors when

analyzing the potential for misappropriation among event attendees, artists, and festival

organizers. This project seeks to insert itself into this conversation by adding nuance to an

unexplored space between these two bodies of scholarship. As this thesis will show, although

misappropriation certainly exists in EDM culture, it frequently happens at the individual level

rather than unilaterally, as EDM artists and attendees create highly personalized meanings

around culturally borrowed material.

Regarding the relative spirituality of dance music events, Graham St. John, a leading

EDM scholar, has analyzed the transformative qualities of EDM culture. Specifically, he has

written about the spiritual origins of the psytrance scene and its subsequent subcultural

transfigurations in his book Global Tribe: Technology, Spirituality, and Psytrance.

32

Psytrance

32

. Graham St. John, Global Tribe: Technology, Spirituality & Psytrance (Bristol, CT: Equinox Publishing, 2012).

18

or Goa trance, which started on the beaches of Goa, India, is a specific style of EDM that

normally lies somewhere between 135–50 beats per minute with bass drum kicks on every

downbeat and some sort of oscillating synthesizer throughout. In addition, Goa trance often

appropriates Indian religious culture, as St. John notes in this passage:

The Oriental spiritual aesthetic intrinsic to Goa was transported around the world in a

sound—and in iconography, cover art and textile fashions—persisting long after

Goatrance had dissipated as a genre. And Oriental motifs were applied as part of an

integralist spiritual technology dedicated to self-transcendence…In the jetstream of the

Goa diasporic movement, projects are conceived and promoted with the intent of

enabling “oneness,” of reconciling the senses, sometimes with quite liberal appropriations

of Hindu discourse.

33

St. John echoes a few of the tenets described by my interviewees, namely the aesthetic

embodiment of spiritual technologies and the idea of “oneness.” In addition, St. John’s use of the

term “Oriental” suggests that he is familiar with the postcolonial theories of Edward Said;

indeed, he makes brief mention of Said elsewhere in his writing. His recognition that these music

scenes freely appropriate from Hinduism’s religious practice also shows awareness of potentially

problematic associations between the two cultures, though he chooses not to address this in

depth.

In other places, St. John discusses ritualization, liminality, and the DJ as “techno-

shaman”—all terms and ideas associated with religious practice, though not problematized as

such in his writings.

34

In St. John’s effort to explicate the heterogeneity of attendees at

psychedelic trance events, he cites John Robert Howard’s use of the term “plastic hippies,”

which connotes participants who adopt the clothing and codes of rebellion of hippie culture

33

. St. John, Global Tribe, 64.

34

. Graham St. John, “Electronic Dance Music: Trance and Techno-Shamanism,” in The Bloomsbury Handbook of

Religion and Popular Music, ed. Christopher Partridge and Marcus Moberg (London: Bloomsbury Publishing,

2017), 278–85; Graham St. John, “Liminal Being: Electronic Dance Music Cultures, Ritualization, and the Case of

Psytrance,” in The Sage Handbook of Popular Music, ed. Andy Bennett and Steve Waksman (London: Sage, 2015),

243–60.

19

without a deeper commitment to ideas of transcendence. These “plastic hippies” stand in contrast

to “visionaries.”

35

St. John also distinguishes between attendees who go to psychedelic trance

events to be intoxicated and avoid responsibility and attendees who wish to raise consciousness

and contribute to a new “planetary culture.”

36

These distinctions show the varying degree of

intention among attendees, not just within the psytrance scene, but across all EDM cultures and

events. While the psytrance festival circuit may have more individuals committed to ideas of

transcendence than its mainstream counterparts, individuals in other EDM cultures may also be

committed to these ideas to varying degrees. I would suggest, then, that a binary of “plastic

hippies” and “visionaries” is reductive even as these terms are useful to describe certain

phenomena in EDM culture—it is not possible to ascertain where any given individual lies on

this spectrum only by looking at them or even having a short-lived interaction with them. As

individuals construct personal meanings behind their own brand of spirituality, reducing this

question to an oversimplified binary obscures the nuances among individual beliefs.

In contrast to St. John’s relative acceptance of religious appropriation is scholar Kaitlyne

Motl, who talks about the ways music festival goers adopt a “colorblind racial ideology” when

responding to accusations about the appropriative nature of EDM culture.

37

Utilizing fieldwork

data collected from large mainstream EDM festivals around the Midwestern United States, she

addresses how mostly white participants adopt temporary costumes to express values of EDM

culture: “cosmopolitanism, travel, experience, community, and a sense of cultural and spiritual

enlightenment.”

38

These cultural values are nearly identical to those that St. John praises

35

. Graham St. John, “The Logics of Sacrifice at Visionary Arts Festivals,” in The Festivalization of Culture, ed.

Andy Bennett, Jodie Taylor, and Ian Woodward (New York: Ashgate Publishing, 2014), 53.

36

. St. John, “The Logics of Sacrifice,” 54.

37

. Kaitlyne Motl, “Dashiki Chic: Colorblind Racial Ideology in EDM Festival Goers’ ‘Dress Talk,’” Popular

Music and Society 41 (2018): 250-69.

38

. Motl, “Dashiki Chic,” 255.

20

throughout his work; indeed, many of them might derive from the psytrance scene (St. John

might argue that many psytrance festival-goers are more committed to these ideas than festival-

goers at mainstream EDM events and may thus have a different relation to appropriation than the

subjects of Motl’s research). In Motl’s view, attendees at mainstream EDM events utilize “dress

talk” to be perceived as having cultural values deemed most desirable within the mainstream

EDM community. She argues that adopting clothing, jewelry, and other accessories that contain

an external display of religious symbols simultaneously exalts and exoticizes those religious

cultures. The traditional meaning of those symbols or clothing (such as West African dashikis,

Indian saris, or Native American headdresses) is lost and turned into a consumable commodity

with potentially problematic consequences.

With regard to non-material capital, Alan Nixon and Adam Possamai discuss religion and

the experience of ecstasy, distinguishing between Neo-Pagan, Christian, and what they deem

“secular” rave cultures.

39

Within all three cultures, attendees describe their ecstatic states in

similar ways, whether those states are influenced by psychedelic drug use or not. Discussing

these ecstatic experiences, Nixon and Possemai note that those who experience these ecstatic

states in EDM culture gain some sort of cultural or symbolic capital.

40

Through dancing to

specific music and, in some cases, the consumption of hallucinogenic drugs, individuals gain

access to the cultural capital of having experienced the esoteric or mysterious.

41

These authors

argue that although individuals interpret ecstatic states in different ways according to their

spiritual affiliation (or lack thereof), having accessed these ecstatic states can solidify their

39

. Alan Nixon and Adam Possamai, “Techno-Shamanism and the Economy of Ecstasy as a Religious Experience,”

in Pop Pagans: Paganism and Popular Music, ed. Andy Bennett and Donna Weston (Durham, UK: Acumen, 2013),

145–61.

40

. Pierre Bourdieu, “The Forms of Capital,” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education,

ed. J. Richardson (New York: Greenwood, 1986), 241–58.

41

. Nixon and Possamai, “Techno-Shamanism,” 161.

21

position within a scene. This study also highlights an important range that exists across EDM

events, which can be more religious or spiritual in nature, or more secular or hedonistic in nature.

Although some events may be more secular in nature, religious and spiritual samplings, imagery,

and a common spirituality are still present among many artists and attendees, though possibly to

a lesser or more appropriative degree. At the same time, attendees at more religious or spiritual

events may be there for the sole purpose of consuming alcohol and drugs for pleasure, such that

the lines between appropriative, appreciative, and reverent are easily blurred.

These considerations of consumption, commodification, and capital are echoed in other

scholarly work that highlights another key dimension of EDM events: their relative degree of

political and/or economic subversion. Simon Reynolds, in his extensive documentation of the

origins of EDM, early rave, and its manifestations in the UK (where it was developed and then

exported back to the US), often discusses EDM culture in relation to its gradual

commercialization throughout the 1990s in his book Energy Flash. Writing from a perspective

that focuses on rave’s countercultural aspects that are more punk-like in sensibility than hippie-

esque, he infuses his florid language with cultural and philosophical readings. He addresses the

decline of the German rave scene in the early 1990s, and his reading could be applied to all of

EDM culture as it has developed through to today. As the underground, countercultural

expressions of rave become more popular, they become more commercialized as they are co-

opted by the leisure industry. In other words, rave started out as politically subversive, with

illegal parties thrown in corporatized industrial centers, purposefully co-opting these spaces to

emphasize their anti-capitalist political position. Over time, as businessmen and corporations

noticed that profits could be made by throwing legal, large-scale events, it quickly became

escapist, lacking an overt political message. This results in what he calls a “pleasure-prison,”

22

which strips the subculture of all its subversive undertones, instead focusing on the party.

42

This

anti-commercialist undertone is echoed in the works of St. John and other scholars on psytrance

and counter-cultural rave scenes. While this eventual commercialization of the rave scene is

important to consider, it overlooks the attitudes of attendees at commercial rave events, who

often feel they are part of something politically or socially radical, even as the scene is not as

subversive as its early days in the 1990s. Though commercial EDM events reproduce capitalist

modes of power, they still hold the promise of alternative lifestyles that stand in contrast to a

stereotypical American experience: the nuclear family, conventional social graces, gainful

employment, and the like. These events (arguably) offer escapist temporary autonomous zones

that lie on the peripheries of mainstream American experience.

43

This escapism frames another frequently mentioned dimension of EDM event culture.

Some events elect to be more grassroots oriented and created by attendees and artists, whereas

others are sponsored events that offer attendees amenities without them having to be a part of the

creation process. Grassroots events tend to promote eco-sustainability, often advertising “Leave

No Trace” policies and encouraging attendees to reduce and reuse as much as possible. Speaking

on grassroots festivals in the psytrance scene, Alice O’Grady frames these experiences as

“alternative playworlds,” explaining that adults enter a state of “deep play,” a term taken from

42

. “…what happened to German rave illustrated Deleuze and Guattari’s concepts of ‘deterritorialization’ and

‘reterritorialization.’ Deterritorialization is when a culture gets all fluxed up—as with punk, early rave, jungle—

resulting in a breakthrough into new aesthetic, social and cognitive spaces. Reterritorialization is the inevitable

stabilization of chaos into a new order: the internal emergence of style codes and orthodoxies, the external co-option

of subcultural energy by the leisure industry. Szepanski has a groovy German word for what rave, once so liberating,

turned into: freizeitknast, a pleasure-prison. Regulated experiences, punctual rapture, predictable music. Szepanski

talks of how ‘techno today is stabilized and regulated by an overcoding machine (the combination of major labels,

rave organizations, mass media).’ Rave started as anarchy (illegal parties, pirate radio, social/racial/sexual mixing)

but quickly became a form of cultural fascism. ‘The techniques of mass-mobilization, and crowd-consciousness

have similarities to fascism. Fascism was mobilizing the people for the war machines, rave is mobilizing people for

pleasure-machines…’” Simon Reynolds, Energy Flash: A Journey through Rave Music and Dance Culture (New

York: Soft Skull Press, 2012), 388.

43

. Hakim Bey, T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone (New York: Autonomedia, 1991).

23

anthropologist Clifford Geertz, when attending these events.

44

This state of play is “associated

with having fun, messing around, cutting loose, making believe, experimenting, imagining,

becoming someone else, creating something else, and, ultimately, learning how to be with other

people in the present moment through improvised sociabilities.”

45

Though she speaks here of

psytrance festivals, this concept of play can easily be applied to all music festival environments,

both grassroots and commercial, where similar values are persistent on the dancefloor and

elsewhere. Throughout her article, however, O’Grady distinguishes between psytrance’s

commitment to its countercultural roots and grassroots ideology and more mainstream,

commercial events that produce a large amount of waste. However, she also explains that

“countless stalls” sell a variety of items at psytrance events: “garments bedecked with Om signs

and images of Shiva, multi-pocketed belts, flowing dresses and floral head dresses.”

46

Thus,

while psytrance events may commit to more sustainable practices, monetary exchange still

persists (Burning Man and other “burns” are notable exceptions).

47

Alongside psytrance festivals, which are more popular in Europe than the US, are related

yet dissimilar “boutique,” “transformational,” or “visionary arts” festivals.

48

These events tend to

be more grassroots in nature than their commercialized counterparts. Drawing upon his

44

. Clifford Geertz, “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight,” in The Interpretation of Cultures (New York,

Basic Books, 1973), 412–453.

45

. Alice O’Grady, “Alternative Playworlds: Psytrance Festivals, Deep Play, and Creative Zones of

Transcendence,” in The Pop Festival: History, Music, Media, Culture, ed, George McKa (New York: Bloomsbury

Academic & Professional, 2015), 150.

46

. O’Grady, “Alternative Playworlds,” 157.

47

. “Burns” are a type of festival wherein attendees burn a large totem at the close of each event. These events often

have a “no spectators” approach, meaning everyone must participate in the creation of the festival environment.

They also have “gift economies,” meaning money is forbidden, and people must instead trade with others to gain

access to whatever they might need for the duration of the festival. Her comments also show the scene’s de facto

acceptance of appropriation of Eastern religious culture.

48

. There are many terms for this type of festival, and many within the scene disagree on what term should be used.

For some, “boutique” sounds too erudite and has negative connotations within consumer culture, while “visionary

arts” and “transformational” might sound overly pretentious or self-righteous. I have given all three terms here and

will use them interchangeably.

24

experiences at Raindance Campout (2013–14), Bryan Schmidt discusses the intersection of

technology and aesthetics at these events as they relate to Nicholas Bourriaud’s concept of

“relational aesthetics.”

49

Relational aesthetics value artwork that creates social situations rather

than objects for contemplation, and indeed the boutique festival space is “co-created by

participants and organizers, where the event’s music, dance, sculpture, workshops and ritual

practices become social interstices that facilitate micropractices of intersubjectivity.”

50

These

events, in addition to high-profile musical acts, usually have well-designed and aesthetically

pleasing stages, installation art with which to interact, live painters surrounding the peripheries

of the stages, and workshops during the day that encourage eco-sustainability, self-

transformation, and self-healing. Schmidt notes that the profit motive is still present as in

traditional commercial music festival environments, but vendors, artists, and festival organizers

alike “sacrifice the possibility of a potentially more profitable scale of production in order to

create objects that retain the aura of their creator’s labour.”

51

As the name Raindance Campout suggests, however, artists, attendees, and organizers

often freely appropriate from cultures seen as possessing elements that aid in the quest of

becoming “transcendent,” or returning to nature. As Schmidt notes:

The relative absence of indigenous bodies at events like Raindance speaks particularly

loudly, coinciding with contemporary controversies that display the lack of control

indigenous groups have over their own representation. The ability to view indigeneity as

a mutable category that can be tried on, played with, cast aside or altered if desired

undoubtedly speaks to the privileged position many festivalgoers occupy within the US

racial and cultural hierarchy.

52

49

. Nicholas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 1998).

50

. Bryan Schmidt, “Boutiquing at the Raindance Campout: Relational Aesthetics as Festival Technology,” in

Weekend Societies: Electronic Dance Music Festivals and Event-Cultures, ed. Graham St. John (New York:

Bloomsbury Academic & Professional, 2017), 95.

51

. Schmidt, “Boutiquing at the Raindance Campout,” 100.

52

. Schmidt, “Boutiquing at the Raindance Campout,” 111.

25

While Schmidt recognizes the fraught racial component of this and other festivals’ free

appropriations, the current project more deeply acknowledges the potential for cognitive

dissonance as individual participants simultaneously exalt and problematize a culture with which

they self-identify. They must negotiate their relationship with these problems at the individual

level such that they either justify their own appropriations or change their behavior according to

their personal beliefs. This means that each individual develops a highly personal relationship

with issues of cultural appropriation, and these almost always have ties to their personal spiritual

beliefs.

Importantly, the rendering of EDM events as white spaces is a central component in Arun

Saldanha’s Psychedelic White, which addresses the whiteness of psytrance culture, even though

its roots are distinctly non-white.

53

While researching on the beaches of Anjuna in 2001,

Saldanha noticed that certain spaces in tandem with certain times of day would attract hippies

and ravers, who were usually white. When these spaces became filled with mostly white bodies,

they became “relatively impenetrable for Indians,” which led him to develop his own materialist

theory of race.

54

He coins the term “viscosity of race,” noting that groups of white bodies would

often cluster together, just as groups of Indian bodies would cluster together in spaces where

psytrance music was playing—these tendencies have specific consequences for the psytrance

scene at large. He discusses these in relation to “psychedelic whiteness,” saying,

Sixties exoticist imaginations of India are but one instance of a wider yearning of

adventurous whites to taste, know, pin down, and/or attain otherness. This exoticism not

only betrays the position of those who are imagining—whites—but also begs the

questions what happens to actual white bodies once they engage with nonwhite spaces

and cultures.

55

53

. Arun Saldanha, Psychedelic White: Goa Trance and the Viscosity of Race (Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 2007), 28-43.

54

Saldanha, Psychedelic White, 49.

55

Saldanha, Psychedelic White, 19.

26

Though his argument is nearly impossible to summarize in any succinct way given its complex

roots in materialist, postcolonial, and poststructuralist theory, he nonetheless positions himself as

a critical voice that seeks to make sense of the racial facets of the phenomenon of rave tourism in

India, where tourists often come from countries with historically colonial associations.

St. John responds to Arun Saldhana’s Psychedelic White in his own Global Tribe,

remarking that Saldanha’s theory is a “surprisingly one-dimensional rendering of the politics of

experience in Goa.”

56

St. John goes on to deconstruct Saldanha’s argument, arguing that the

atmosphere of Goa parties is more complex than white people dancing in an Indian space away

from Indian people. He notes that Indian people often occupy privileged positions in the scene,

and conversely that Indian men, domestic tourists to Goa, often predate upon white women, who

are perceived as mythically “loose.” He also mentions unchecked commercialism and police

corruption, remarking that “while many of these agents of predation would have dark skins, none

of their conditions are intrinsically Indian (or racial). Indeed, these are factors threatening

experimental and alternative arts scenes everywhere, and are some of the reasons why freaks

sought Goa to begin with.”

57

In conclusion, he reiterates: “My chief concern is that diverse

expectations, relations and aesthetics are discounted by [the postcolonial] approach, and an entire

cultural movement—identifying with Goa or not—is condemned to answer the charges of neo-

colonialism.”

58

Thus, while St. John recognizes the racial dynamics that prompt examination of

the psytrance festival circuit through a postcolonial lens, he ultimately avoids rather than

addresses the critique by citing the overall heterogeneity of the scene.

56

. St. John, Global Tribe, 67.

57

. St. John, Global Tribe, 67.

58

. St. John, Global Tribe, 69.

27

In summary, EDM scholars tend to either praise EDM culture’s transformative qualities

and spiritual appropriations or to critique them, often quite harshly. The authors in the first camp

tend to be highly laudatory while overlooking or only briefly mentioning and rationalizing power

dynamics that might be problematic. They highlight dance culture’s potentially subversive

qualities: creating utopian-like societies, challenging the status quo of consumerism and

capitalism, and in the case of some alternative EDM cultures, eco-sustainability. The authors in

the latter camp focus on the appropriative or gentrified aspects of EDM culture. Scholars writing

from this perspective point out that EDM’s fan base is comprised of mostly white people though

its origins are primarily non-white. They often problematize EDM culture’s ties to consumerism.

These scholars position themselves in direct contrast to scholars who argue in support of EDM’s

transformative and perhaps socio-politically challenging qualities. My project intervenes at the

intersection of these two bodies of scholarship, arguing that EDM culture is hardly one-

dimensional, and its various subscenes cannot be treated uniformly. In addition, attendees of a

specific event cannot be treated en masse, as not all individuals attend events with the same

values and intentions, as I show through excerpts from interviews with individual participants.

Overview

The next three chapters will focus on three separate iterations of the bass music scene as

spearheaded by artists who stand as representatives for their respective subscenes: Desert

Dwellers, TroyBoi, and Bassnectar. Desert Dwellers stand at the forefront of the music and

culture of the psychedelic downtempo genre, which often has the most overt association with the

spirituality discussed in this project. TroyBoi is a multiethnic trap music artist who often draws

from many cultures around the world; though he may not be personally spiritual, participants at

28

many of his live events are. Bassnectar is a widely popular dubstep DJ who is often regarded as a

de facto spiritual leader by his fans. Recent controversies in his personal life have challenged

how EDM concertgoers engage in worship of DJs they love, and this may indeed be one of the

negative repercussions of spiritual appropriation. Synthesizing these case studies with ideas from

interviewees, a picture emerges in which artists and participants must navigate conversations

about appropriation in order to justify their commitment to their personal brands of spirituality.

29

Chapter 2

Psychedelic Downtempo: Desert Dwellers

Beginning with the most overtly spiritual of the artists to be considered in this project,

Desert Dwellers are a duo of electronic music producers named Amani Friend and Treavor

Moontribe who freely assimilate sounds and symbolism from multicultural contexts. According

to their website, Desert Dwellers were “brought together in the late ‘90s through the legendary

Moontribe gatherings, [and] in 2019 the duo celebrated their 20

th

anniversary of making music

together, adding depth to their reputation as a pioneering and prolific downtempo, psybass, and

tribal-house act from the United States.”

59

This bio situates Desert Dwellers’ role within EDM

culture in three important ways. The first is that Desert Dwellers got their start at Moontribe

gatherings, events that are akin to the “transformational” music events previously described. The

second is their “reputation as pioneers” who have been making music for over 20 years. The

third is their style of music, which infuses downtempo, psybass (a term that derives from a

combination of “psytrance” and “bass” music), and tribal-house (“tribal” as an exoticist

evocation rather than in a literal sense).

Desert Dwellers make music that infuses elements of psytrance with bass music.

Psytrance is a subgenre of EDM that is perhaps most closely associated with India given its

origins in Goa, India.

60

Whereas psytrance normally lies somewhere between 135–50 beats per

59

. “Bio,” Desert Dwellers, accessed October 20th, 2020, https://www.desertdwellers.org/bio/.

60

. Psytrance’s roots are in 1960s psychedelic culture, which had been imported to the beaches of Anjuna in Goa,

India by foreign travelers. The most notable of these travelers is “Goa Gil,” who left San Francisco and arrived in

Goa in 1970. After firmly establishing Goa as a place of psychedelic refuge, DJing became a key feature of dance

parties there throughout the late 70s and 80s. By 1986, music in Goa was exclusively electronic, allowing for the

development of a new type of music marketed in 1993–4 as “Goa trance” and exported from Goa to the UK,

continental Europe, and eventually the United States and elsewhere around the globe. The Goa sound was then

further developed, branching out into many subgenres that form the umbrella term “psytrance.”

30

minute with bass drum kicks on every downbeat and some sort of oscillating synthesizer

throughout, psybass tends to take a more relaxed approach (other related genres include psydub,

psybient, or the umbrella term “psychedelic downtempo,” used henceforth). The clearest link

between the two is in the material they sample, which is often taken from science fiction, popular

psychedelic philosophers (Timothy Leary or Terence McKenna, for example), or soundscapes

from Hindu or Buddhist teachings. This “sampledelia” is utilized to encourage states of deep

trance (for psytrance) or deep meditation (for psychedelic downtempo).

61

In fact, Desert

Dwellers have a whole series of albums meant to accompany the practice of yoga.

62

While psytrance’s states of deep trance dance primarily occur on the dance floor,

psychedelic downtempo can be applied in many situations: private affairs such as personal

meditation or yoga, public events at outdoor festivals, and even nightclubs. Reading further into

their bio, the group states:

Desert Dwellers’ studio output is matched only by their extensive touring history, which

juxtaposes performances at America’s most iconic festivals like Symbiosis, Lightning in

a Bottle, Burning Man, and Coachella, with high-powered sets at the biggest trance

festivals around the world; BOOM in Portugal and Rainbow Serpent in Australia. Desert

Dwellers are equally at home in the clubs as they are in the yoga studios, and the jungles,

deserts, and mountains of far-flung international festivals.

63

This statement shows the versatility of their performance/listening spaces, as they perform at

both transformational festivals (Symbiosis and Lightning in a Bottle) and mainstream festivals

(Coachella). Their music is therefore heard by people who may or may not understand or

resonate with its spiritual message, though it is assumed that people who identify as either

61

. This is a term used by EDM scholars to describe the style of samples that frequently occur in a specific genre of

EDM music.

62

. Desert Dwellers, Jala Yoga Flow, Bandcamp, 2010; Desert Dwellers, Satori Yoga Dub, Bandcamp, 2010; Desert

Dwellers, Asudha Yoga Dub, Bandcamp, 2010; Desert Dwellers, Muladhara Yoga Dub, Bandcamp, 2011; Desert

Dwellers, Anahata Yoga Dub, Bandcamp, 2012.

63

. “Bio,” Desert Dwellers, https://www.desertdwellers.org/bio/.

31

spiritual or non-spiritual might enjoy listening or dancing to their music. Attendees bring their

own spiritual practices (or lack thereof) to these events. While some are interested only in the

party, others take their commitment to spiritual ideas seriously. Thus, though Desert Dwellers’

intention in writing this music is appreciative and perhaps not overly caricaturized, the potential

disconnect between artist and audience creates room for misappropriation that individuals must

navigate and ultimately justify or avoid. In this chapter, I show how Desert Dwellers project a

sense of spirituality through the music create, specifically by sound-sampling music of “the

other” or by evoking it through imitation. I then situate their music in relation to the types of

festivals and events at which they frequently perform. Finally, I describe how my interviewees,

many of whom are fans of this music, navigate conversations about appropriation with regard to

this style of music.

“Saraswati’s Twerkaba” and Sound Sources

A primary example of Desert Dwellers’ overt spiritual syncretism is the 2016 song

“Saraswati’s Twerkaba.” The song’s title—which simultaneously references the Hindu goddess

Saraswati, Jewish mysticism (Merkaba), and a popular dance style associated with hip-hop

32

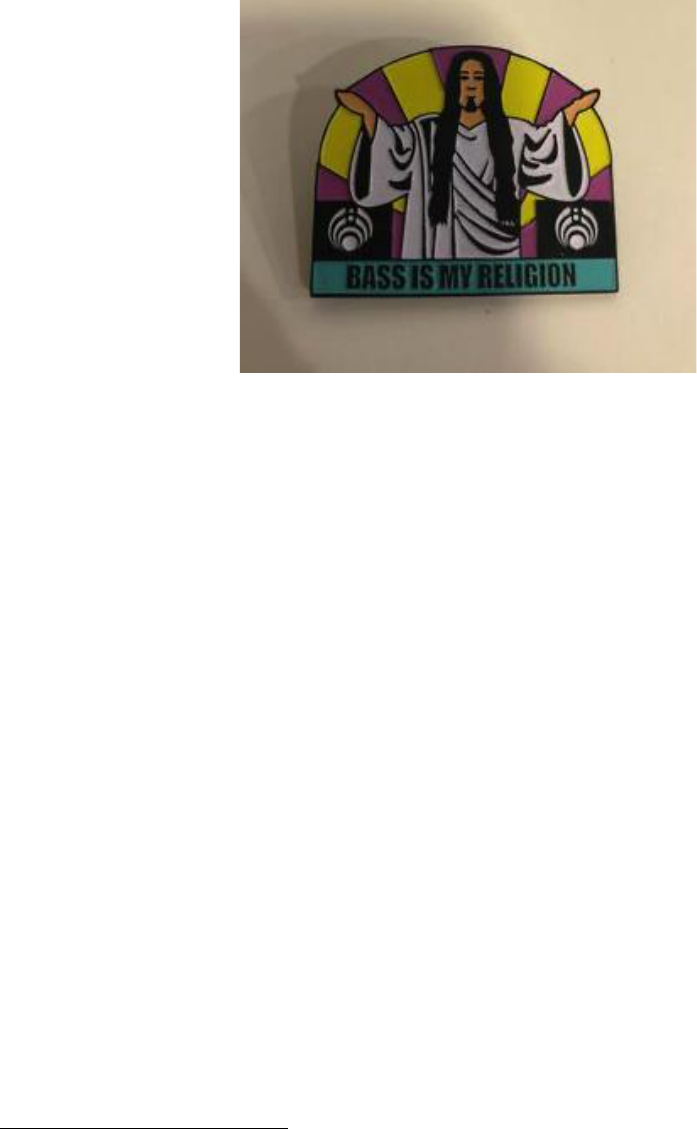

(“twerking”)—also highlights the syncretic nature of their music. The album artwork depicts the

Hindu goddess surrounded by a fractal pattern of speakers (shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Album artwork for “Saraswati's Twerkaba”

The track begins with a gong-like invocation, immediately signaling its meditative undertones to

the listener. There is no steady beat until about 0:44, and instead the track blends ethereal

synthesized sounds with ambiguous, non-rhythmic percussion. The sampled Indian tabla begins

at this point along with a bassline, which combined emphasize a steady beat at around 85 bpm

with a tonal center of E. The modal-like scalar pattern used throughout the song further

exoticizes its sound: it is similar to E Phrygian, though with an omnipresent raised third, also

known as Phrygian dominant—the augmented second between the lowered second scale degree

and the raised third scale degree adds to its exoticism.

64

Though this scale is used here to connote

64

“The illicit augmented-second interval [has] long been the musical sign for the Jew, the Arab, the all-purpose