americanchemistry.com

®

700 Second St., NE | Washington, DC 20002 | (202) 249.7000

September 6, 2022

Electronic Submission

Honorable Robin Carnahan

Administrator

U.S. General Services Administration

1899 F Street, NW

Washington, D.C. 20405

In re: Case 2022-G517: Public Comments: Advanced Notice of Proposed

Rulemaking: Single-Use Plastics and Packaging (87 FR 40476)

Dear Administrator Carnahan,

The American Chemistry Council (ACC) appreciates the opportunity to submit the attached

comments to the General Services Administration (GSA) regarding the Advanced Notice of

Proposed Rulemaking: Single-Use Plastics and Packaging.

ACC and our members are deeply committed to creating a more circular economy for

plastics and ending used plastic in the environment. That is why ACC and our Plastics

Division members were among the first to establish ambitious, forward-thinking goals that

all plastic packaging in the United States is reused, recycled, or recovered by 2040 and that

all U.S. plastic packaging is recyclable or recoverable by 2030.

1

Achieving these goals will require industry, manufacturers, brands and retailers, recyclers,

and waste haulers, as well as citizens, communities, non-profits, academics, and federal,

state, and local governments, to come together to support policies and programs to increase

the supply of and demand for recycled materials and create the circular economy we all

want.

We believe that a rule based on this ANPR would:

• Lead to the unintended consequence of increasing greenhouse gas (GHG)

emissions contrary to the president’s climate goals;

• Increase public costs; and

• Increase the amount of materials landfilled.

1

“U.S. Plastics Resin Producers Set Circular Economy Goals to Recycle or Recover 100% of Plastic

Packaging by 2040,” Media release (American Chemistry Council, May 9, 2018),

https://www.americanchemistry.com/chemistry-in-america/news-trends/press-release/2018/us-

plastics-resin-producers-set-circular-economy-goals-to-recycle-or-recover-100-of-plastic-packaging-by-

2040.

americanchemistry.com

®

700 Second St., NE | Washington, DC 20002 | (202) 249.7000

A better solution would be for the GSA to (1) create a purchasing preference for items with

recycled plastics as well as (2) base procurement decisions on lifecycle assessments (LCA) to

help ensure science-based climate decisions. Additionally, Congress should (1) require a 30

by ’30 national recycled plastics standard, (2) create a modern regulatory system to develop

a circular economy for plastics, (3) develop national recycling standards for plastics, (4)

study the impact of greenhouse gas emissions from all material to guide informed policy,

and (5) support an American-designed producer responsibility system.

2

While we would not support a proposed rule reflecting the direction of the ANPR,

3

we offer

these comments in support of the larger goals of reducing climate impact and waste and

increasing recycled content and the circular economy.

4

ACC would welcome the opportunity to meet with the GSA to discuss our comments in

greater detail. In the interim, please feel free to contact me at +1 (202) 249-6600 or

Joshua_Baca@AmericanChemistry.com or Adam S. Peer, Senior Director, Plastic Packaging

& Consumer Products at +1 (202) 249-6614 or Adam_Peer@AmericanChemistry.com.

Sincerely,

Joshua Baca

Vice President, Plastics Division

American Chemistry Council

Attachments

2

Plastic Division, “5 Actions for Sustainable Change,” Industry report (Washington, D.C.: American

Chemistry Council, 2021),

https://www.plasticmakers.org/files/d6b3a34b9a88b1a6ee4da0a73b24562d740f80e4.pdf.

3

ACC reserves the right to raise additional concerns.

4

Specific responses may be found in Table 1 on page 18. In some cases, ACC does not respond

directly because the ANPR is based on an incorrect assumption.

3

Public Comments: Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking:

Single-Use Plastics and Packaging

(Case 2022-G517, 87 FR 40476)

Introduction

The American Chemistry Council's (ACC)

5

Plastics Division

6

is pleased to submit these

public comments to the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), Office of Acquisition

Policy’s Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR) (87 F.R. 40476) relating to:

General Services Administration Acquisition Regulation (GSAR) relating to: Single Use

Plastics and Packaging (Case 2022-G517).

ACC and our members are deeply committed to creating a more circular economy for

plastics and ending used plastic in the environment. That is why ACC and its Plastics

Division members were among the first to establish ambitious, forward-thinking goals that

all plastic packaging in the United States is reused, recycled, or recovered by 2040 and that

all U.S. plastic packaging is recyclable or recoverable by 2030.

7

Achieving these goals will

require industry, manufacturers, brands and retailers, recyclers, and waste haulers, as well

as citizens, communities, non-profits, academics, and federal, state and local governments

to come together to support policies and programs to increase the supply of and demand for

recycled materials and create the circular economy we all want.

We believe that a rule based on this ANPR would:

• Lead to the unintended consequence of increasing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions

contrary to the president’s climate goals;

• Increase public costs; and

• Increase the amount of materials landfilled.

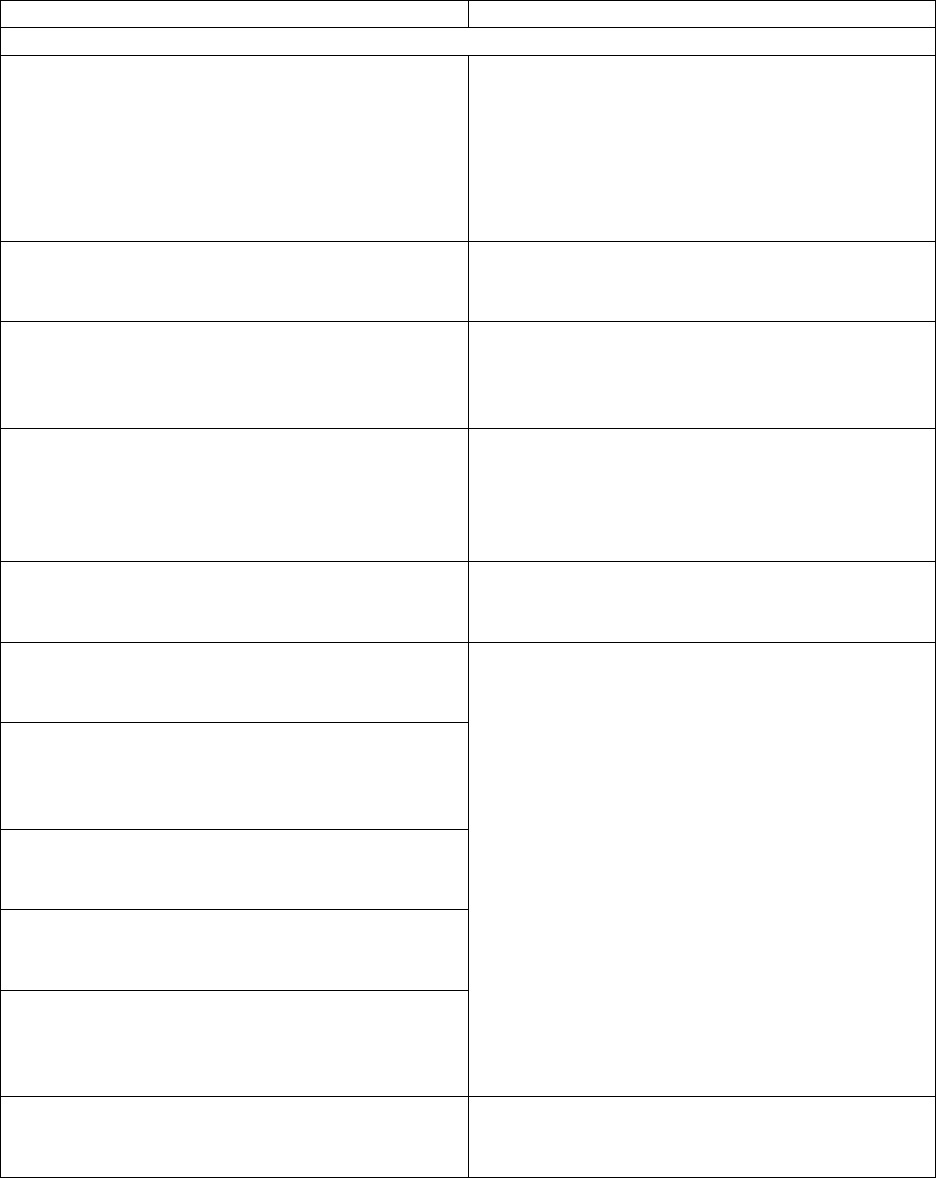

A better solution would be for the GSA to (1) create a purchasing preference for items with

recycled plastics as well as (2) base procurement decisions on lifecycle assessments (LCA) to

help ensure science-based climate decisions. This is illustrated in Figure 1 on page 23.

Additionally, Congress should (1) require a 30 by ’30 national recycled plastics standard, (2)

create a modern regulatory system to develop a circular economy for plastics, (3) develop

national recycling standards for plastics, (4) study the impact of greenhouse gas emissions

5

ACC represents a diverse set of companies engaged in the U.S. business of chemistry, a $768 billion

enterprise that is helping to solve the biggest challenges facing our country and the world.

Chemistry touches 96 percent of all manufactured goods, and the use of plastics in modern

automotive, building and construction, and food packaging industries is helping to create a more

sustainable society

6

The Plastics Division of the American Chemistry Council (ACC) represents leading manufacturers

of plastics, as well as other companies throughout the entire plastics value chain, and focuses

on advocacy initiatives that promote sustainability and contribute to a more circular economy for

plastics.

7

“U.S. Plastics Resin Producers Set Circular Economy Goals to Recycle or Recover 100% of Plastic

Packaging by 2040.”

4

from all material to guide informed policy, and (5) support an American-designed producer

responsibility system.

8

While we would not support a proposed rule in the direction of the ANPR,

9

we offer these

comments in support of the larger goals of reducing climate impact and waste and

increasing recycled content and the circular economy.

10

We look forward to working constructively with the GSA and other stakeholders on a

proposed rule that would achieve a more circular economy for plastics in the United States.

Environmental Impacts

Increased Climate Effect

The ANPR seems to mistakenly assume that alternatives to plastics are always

environmentally preferable to non-plastic materials in the single-use and packaging

context. Although plastic has a carbon footprint, it is mistaken to assume that alternative

materials would always be more effective.

11

It is important to consider the carbon benefits

of using plastics.

12

As illustrated in Figure 1 and discussed further on, we are concerned by

any blanket approach that merely substitutes plastics with alternatives, without taking

into account the overall environmental footprint and total lifecycle impact of the alternative

materials. Taking this approach in the absence of scienced-based analysis will in turn lead

to increased greenhouse gas emissions and increased landfill.

Rather than making blanket assumptions that could have unintended consequences, GSA’s

proposed rule should be guided by LCAs. One of the most powerful impacts of the proposed

rule will be its overall impact on the environment, from a lifecycle perspective.

An LCA is a valuable tool for evaluating the environmental impacts of packaging

alternatives over their lifecycle, from the extraction of raw materials to the disposal or

recycling of an item.

13

When we consider the environmental impacts of packaging

throughout its entire lifecycle (mining, manufacturing, transportation, use, and end-of-life),

LCAs are essential to compare the environmental performance of alternative materials for

different applications.

14

The President directed that science- and evidence-based tools, such as LCAs, should guide

climate-related decisions. The President has stated in his executive order "Tackling the

Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad" that the government should listen to science and take

8

Plastic Division, “5 Actions for Sustainable Change.”

9

ACC reserves the right to raise additional concerns. See, Table 1 on page 18.

10

Specific responses may be found in Table 1 on page 18. In some cases, ACC does not respond

directly because the ANPR is based on an incorrect assumption.

11

N. Voulvoulis et al., “Examining Material Evidence: The Carbon Footprint” (Imperial College

London, 2020), https://www.americanchemistry.com/better-policy-

regulation/plastics/resources/examining-material-evidence-the-carbon-fingerprint.

12

Voulvoulis et al.

13

Olivier Jolliet et al., Environmental Life Cycle Assessment (CRC Press, 2015),

https://doi.org/10.1201/b19138.

14

Jolliet et al.

5

action to address the effects of climate change.

15

Additionally, the President directed that

agencies must capture the full costs of GHG emissions under the executive order

"Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the

Climate Crisis."

16

Calculations of this nature must be as accurate as possible and consider

global damage as well. The President recognized that this facilitates sound decision-

making, acknowledges the breadth of climate impacts, and supports the international

leadership of the United States. ACC supports this approach.

In a recent study, plastic lowered total GHG contribution in 13 of 14 cases compared to

alternatives in cases where it was used at scale.

17

&

18

The study demonstrated that in

terms of both product lifecycle and use impact, GHG savings range from 10 to 90 percent.

Many applications, particularly in food packaging, do not have a viable alternative in terms

of performance. Moreover, plastics adoption in additional areas could contribute to

decarbonization by reducing food spoilage and energy use, resulting in even lower GHG

emissions.

In an analysis of 20 common food categories, including fresh and frozen meat, more than 90

percent of the products use plastic packaging.

19

Over 50 percent of products in another

eight categories are packaged with plastic.

20

Plastics have a significant impact on

greenhouse gas emission avoidance.

21

For example:

22

• As a result of their lightweight properties and low energy requirements, PET bottles

produce the lowest emissions compared to alternatives.

• The GHG emissions from metal cans are three times higher than those from

multilayer plastic pouches.

• Use of plastic packaging for meat preservation reduces GHG emissions by 35

percent compared to butcher paper.

• The GHG emissions from reusable plastic bottles of hand soap are 15 percent lower

than those from reusable glass bottles.

According to another report, on a global scale, other packaging types (fiber, glass, steel, and

aluminum) emit more greenhouse gases than plastic bottles when considering the

production and manufacturing of the main alternatives to plastic for a 500ml bottle.

23

Glass

bottles were found to emit the most greenhouse gases among materials studied.

Additionally, the report suggests that replacing all plastic bottles with glass globally would

15

“Exec. Order No. 14008, Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad,” 86 F.R. § 19 (2021),

https://www.regulations.gov/document/EPA-HQ-OPPT-2021-0202-0012.

16

“Exec. Order No. 13990 Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science To

Tackle the Climate Crisis,” 86 F.R. § 14 (2021), https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2021-01765.

17

David Feber et al., “Climate Impact of Plastics,” Industry report (McKinsey & Company, July

2022), https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/chemicals/our-insights/Climate-impact-of-plastics.

18

Note, the study included some durable applications.

19

Feber et al., “Climate Impact of Plastics.”

20

Feber et al.

21

Feber et al.

22

Feber et al.

23

Voulvoulis et al., “Examining Material Evidence: The Carbon Footprint.”

6

result in 22 large coal-fired power plants' worth of additional carbon emissions.

24

That

amount of electricity is consumed by one third of the United Kingdom.

25

It is easy to

overlook plastic's positive impact because of its ubiquitous nature, and critical to ensure

that GSA fully consider the impact in its proposed rule to help federal agencies reduce

Scope 2 and 3 emissions as required by executive order.

26

The use of plastic also reduces

food spoilage and landfill waste, both priorities of the administration.

Increase Landfill of materials

Plastics have largely replaced glass, paper, and cardboard materials for containers and

packaging due to performance efficiencies.

27

Compared to glass, metal, paper and cardboard

containers and packaging, plastic containers and packaging tend to use significantly less

material.

28

On average, over four times more alternative material is needed to perform the

same function.

29

This means that if plastic containers and packaging are replaced by

common material alternatives, it will likely lead to increased landfilling of materials.

A recent Canadian regulatory impact assessment (RIA) demonstrates this. The RIA applied

to a regulation banning certain plastic items. According to the RIA, the proposed regulation

is expected to increase waste generated by substitutes by 298,054 tons in the first year and

by 3.2 million tons from 2023 to 2032.

30

During that same time, the regulation would

prevent approximately 1.6 million tons of used plastics but would add 3.2 million tons of

other materials to the waste stream.

31

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, plastics accounted for 12.2 percent

of waste in 2018.

32

During the past eight years, plastic durable goods, containers, and

packaging have varied between 12.2 percent and 13.2 percent.

33

In 2018, 146.1 million tons

of waste were landfilled in the United States. Food accounted for 24 percent of waste

landfilled.

34

24

Voulvoulis et al.

25

Voulvoulis et al.

26

“Exec. Order. No. 14057, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal

Sustainability,” 86 F.R. § 236 (2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-12-13/pdf/2021-

27114.pdf.

27

Demetra A. Tsiamis, Melissa Torres, and Marco J. Castaldi, “Role of Plastics in Decoupling Municipal Solid

Waste and Economic Growth in the U.S.,” Waste Management 77 (July 2018): 147–55,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.05.003.

28

Tsiamis, Torres, and Castaldi.

29

Richard Lord, “Plastics and Sustainability: A Valuation of Environmental Benefits, Costs, and Opportunities

for Continuous Improvement” (American Chemistry Council, July 2016),

https://www.plasticpackagingfacts.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ACC-report-July-2016.pdf.

30

Kenneth P Green, “Canada’s Wasteful Plan to Regulate Plastic Waste,” 2022,

https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/canadas-wasteful-plan-to-regulate-plastic-

waste.pdf.

31

Green.

32

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials,

Wastes and Recycling,” October 2, 2017, https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-

waste-and-recycling/national-overview-facts-and-figures-materials.

33

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

34

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

7

Should GSA move forward with a proposed rule that is designed to categorically minimize

all “single use” plastic packaging, landfilling is likely to increase rather than decrease due

to landfilling of alternatives and an increase in food waste discussed further below. Federal

agencies are unlikely to achieve the President's goal

35

of reducing waste and diverting at

least 50 percent of non-hazardous solid waste from landfills should GSA move forward

consistent with the direction of the ANPR. The ANPR would also make the President’s goal

of reducing food waste more difficult to achieve.

36

Increase Food Waste

Nearly a third of all food produced worldwide for human consumption never reaches people,

according to the United Nations.

37

This not only represents a missed opportunity to

increase food security, but also wastes the natural resources needed to grow, process,

package, and transport food. Food waste makes up 24 percent of landfilled material.

38

This

results in enormous amounts of methane. The global warming potential of methane is 84 to

86 times greater than that of carbon.

39

As a country, food waste would rank third in GHG

emissions.

40

We support the President’s efforts

41

to reduce food waste as well as highlight

the social cost of methane.

42

Modern food systems rely on plastic to protect and preserve food during transport from

farm through to the consumer. Food spoilage would be much higher without plastics. Food

spoilage is greatly reduced by the widespread availability of modified atmosphere

packaging (MAP).

43

In MAP packaging, a perishable product is packed in an atmosphere

containing different elements from air, which slow the spoilage process.

44

For example, plastic packaging has been shown to increase the shelf life of:

• Cucumbers from 3 to 14 days

45

35

Exec. Order. No. 14057, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal

Sustainability.

36

Exec. Order. No. 14057, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal

Sustainability.

37

Food & Agriculture Organization, “Food Wastage Footprint & Climate Change,” Fact sheet

(United Nations, November 2015), https://www.fao.org/3/bb144e/bb144e.pdf.

38

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials,

Wastes and Recycling.”

39

International Society of Professional Sustainability Professionals, ISSP-SA Study Guide, 1st Ed.

(Portland, OR, 2016).

40

Food & Agriculture Organization, “Food Wastage Footprint & Climate Change.”

41

Exec. Order. No. 14057, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal

Sustainability.

42

Exec. Order No. 13990 Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science To

Tackle the Climate Crisis.

43

Michael Mullan, “Science and Technology of Modified Atmosphere Packaging,” Dairy Science,

January 2011, https://www.dairyscience.info/index.php/packaging/117-modified-atmosphere-

packaging.html.

44

Mullan.

45

Advisory Committee on Packaging, “Packaging in Perspective,” Industry report (Packaging

Federation, October 2008), https://www.thefactsabout.co.uk/file.php?fileid=28.

8

• Lettuce from 2 – 4 to 14 days

46

• Fresh red meat from 2 – 3 to 21 days

47

• Fresh pasta from 3 to 60 days

48

• Cheese from 7 to 180 days.

49

The benefits of plastic packaging include ease of opening and resealing, which extends food

shelf life and gives convenience to people.

50

While MAP has been used for food storage for

more than a century, advances in polymer science have made it possible to apply this

knowledge to modern food technology with the introduction of plastic films that are suitable

for food storage.

51

ACC believes that a proposed rule that focuses solely on diversion of

”single use” plastics packaging will also increase public costs in addition to its negative

environmental impacts.

Evidence-based public policy should guide GSA decision making. Resources, manufacturing,

and transportation are required for the creation, use, recycling, or disposal of any item. An

item's total environmental impact, as well as societal and economic factors, should be

considered by decision makers. The same should be done for plastic alternatives and the

externalities caused by alternatives.

Increased Public Costs

Along with environmental costs, the ANPR implies an approach that, if adopted in the

proposed rule, would have a negative fiscal impact. Generally, plastic alternatives are more

expensive than plastic to purchase and transport due to increased weight. It is unclear how

this increase in cost will be budgeted. Additionally, the proposed rule could adversely affect

small businesses doing business with the federal government. It is difficult to properly

estimate the impact of such a proposed rule without further information about what GSA

envisions, but Virginia's attempt to eliminate single use plastic procurement offers insight.

The prior governor issued an executive order that would have prohibited state government

agencies and universities from using “single-use” plastic products in part to "reduce [the]

amount of solid waste going to landfills."

52

A limited analysis of state expenditures for the Virginia executive order concluded it would

have nearly doubled the costs of foodservice products for state agencies.

53

In that analysis,

46

Todd Bukowski and Michael Richmond, “A Holistic View of the Role of Flexible Packaging in a

Sustainable World,” Industry report (Flexible Packaging Association, April 9, 2018),

https://perfectpackaging.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/FPA-Holistic-View-of-Sustainable-

Packaging.pdf.

47

Bukowski and Richmond.

48

Bukowski and Richmond.

49

Bukowski and Richmond.

50

Bukowski and Richmond.

51

B. Ooraikul and M. E. Stiles, eds., Modified Atmosphere Packaging Of Food (Boston, MA: Springer

US, 1995), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-2117-4.

52

“Exec. Order No. 77,” Vol. 37, Iss. 17 Va. Reg. Regs. § (2021),

http://register.dls.virginia.gov/vol37/iss17/v37i17.pdf.

53

MB Public Affairs, Inc., “Initial Comments on Virginia Executive Order Number 77 (2021),” April

4, 2021.

9

it found in Virginia that about half of the food services were provided by the Virginia

Department of Education for school lunches, breakfasts, summer meals, and other nutrition

programs. Additionally, costs would have increased for food services provided by the

criminal justice system, higher education, mental health, senior services, vocational

rehabilitation, and services for the visually impaired. That analysis also found that the

Virginia nutrition expenditures were $13.4 million in expanded polystyrene foam and rigid

plastics disposable foodservice purchases, which would have increased 75 to 118 percent

under the Virginia ban, or $10.1 million to $15.8 million. Clamshells, beverage and portion

cups, lids, containers, dinnerware (plates and bowls), food trays, and serving trays and

carriers were included in these estimates. Estimates do not include straws, utensils, or

trays for meat, poultry, fish, or eggs or other items that the ANPR could affect.

Vendors of food to Virginia would have faced higher food service costs. According to the

same analysis, vendors and concessioners serving government agencies, higher education

institutions, public safety agencies, and prison systems would have needed to find new

suppliers and increase their operational expenditures.

54

Profit margins are generally low in

food service operations. According to the Restaurant Association's Restaurant Operations

Reports, 3 percent of profits come from full-service restaurants and 6 percent from limited-

service restaurants. A full-service restaurant's disposable plastic food service accounts for

0.3 percent of revenues, a fast-casual restaurant's 0.6 percent, a quick-service restaurant's

1.3 percent, and a coffee shop's 2.3 percent. A forced shift to specific foodservice products

could consume from 5 percent to nearly 40 percent of business profits at a 6 percent

operating profit margin.

A study in Maryland estimated a more restrictive statewide prohibition on plastic products

would result in an additional $34.9 million annually to replace the restricted products.

55

That for every $1 now spent on expanded polystyrene foodservice products, replacement

alternatives on average would costs $1.85.

56

Virginia has since rescinded this order in favor of recycling and other steps to create a more

circular economy.

57

ACC suggests a similar approach discussed further in our comments.

Legal Authority

ACC also questions whether and to what extent the GSA’s consideration of broad new

purchasing mandates or prohibitions relating to plastic as a material is consistent with

existing statutory authority. The GSA’s (and the President’s) authority to formulate

entirely new federal policies to drive government procurement is not unfettered.

54

MB Public Affairs, Inc.

55

MB Public Affairs, Inc., “Fiscal Impacts of Prohibiting Expanded Polystyrene Food Service

Products in Maryland: SB 186 & HB 229,” Industry report, 2017,

https://www.plasticfoodservicefacts.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Maryland-2017-fiscal-impact-

study-of-SB-186-and-HB-229.pdf.

56

MB Public Affairs, Inc.

57

“Exec. Order No. 17 Recognizing the Value of Recycling and Waste Reduction,” Pub. L. No. E.O. 17

(2022), https://www.governor.virginia.gov/media/governorvirginiagov/governor-of-virginia/pdf/eo/EO-

17-Recognizing-The-Value-of-Recycling-and-Waste-Reduction.pdf.

10

We are not aware of any existing statutory authority that directs or would support a federal

procurement policy to disapprove or otherwise require substitutes for plastic packaging,

particularly considering its comparative high-performance functionality and low-cost

relative to competing materials.

Indeed, courts have held that the President’s exercise of general authority under the

Procurement Act requires that procurement policies have a “sufficiently close nexus” to the

statutory objectives of promoting “economical” and “efficient” government

purchasing. Even a broad and elastic interpretation of that authority would have difficulty

justifying a new procurement rule that, for example, sought to generally phase out “single-

use” plastic packaging from federal contracts. If GSA proceeds to the proposal of a rule

regarding plastic procurement, therefore, it will be important for GSA to clearly and

carefully identify the sources of statutory authority for the policies and measures that it

proposes to adopt.

Alternative Policy

While ACC does not support the ANPR’s “reducing single-use plastics” approach, ACC does

support the President’s goals of using federal procurement policy to (1) help address climate

change,

58

and (2) reduce waste, support recycled content markets, and circular economy

approaches.

59

Rather than the current approach, ACC urges the GSA to (1) base

procurement decisions on a total lifecycle analysis to ensure science-based decisions, and (2)

to create a purchasing preference for items containing recycled plastics. Additionally,

Congress should (1) create a modern regulatory system to develop a circular economy for

plastics, (2) develop national recycling standards for plastics, and (3) support an American-

designed producer responsibility system.

GSA Action

Incent Recycled Content

There is unprecedented momentum globally for developing a circular economy that can

benefit society and the environment. ACC believes that federal procurement policies could

help to develop a means for valuable and highly efficient plastic material to be reused again

and again rather than treated as waste. This will also help enabling a more circular

economy for plastics, and (in contrast to a generally applicable phase out of plastic

packaging as such) would likely contribute to economical and efficient government

procurement, consistent with the Procurement Act. In addition, the federal government

already has a statutory mandate to establish and implement recycled content mandates for

federally purchased goods, through the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (42 U.S.C.

6962), which EPA currently administers through its Comprehensive Procurement

Guideline Program.

58

Exec. Order No. 14008, Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad.

59

Exec. Order. No. 14057, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal

Sustainability.

11

The GSA could enhance the circularity of plastics by working with EPA to establish a

strong purchasing preference that encourages procurement of products made from recycled

plastic. For example:

• Create policies that give recycled plastics containing products purchasing preference

• Create resources that educate and equip purchasing officers to increase recycled

plastics procurement and recycling

• Give greater employee recognition for increasing agency procurement of recycled

plastics and recycling.

Procurement policy can help increase domestic demand for recycled plastics. Increasing

purchasing of plastics with recycled content promotes the use of recycled content in

manufacturing new products. The net effect is supporting the growth of green

manufacturing and green jobs.

Compostable plastics play an important role in creating a circular economy. GSA should

consider including compostable plastics in procurement policy. For example, creating

procurement preferences that recognize the unique value and nature compostables

contribute to circularity.

For example, as introduced, legislation in Virginia would have required agencies to give

preference to materials containing recycled content so long as those materials offer a cost

competitive advantage.

60

As enacted, the state must identify recycled content in procured

plastic materials and may use the information to award a bid.

LCA Guided Decision-making

As previously stated, it is erroneous to assume that plastic alternatives will always perform

better. The total carbon benefits of plastics must be considered. LCAs should guide GSA

decision making.

61

Several factors influence the LCA results, including shipping distance and method of

transportation, inputs in the manufacturing process package design, how a product is used

and disposed.

62

Consideration should also be given to the full life cycle of the material.

63

Waste management routes used for the end-of-life treatment of packaging are also shown to

be critical to understanding variations in LCA results.

64

Environmental indicators strongly suggest that recycling outperforms virgin production.

65

Recycling plastics saves between 30 and 80 percent of the carbon emissions produced

during virgin plastic processing and manufacturing.

66

It is for this and other reasons that

GSA should incentivize the use of recycled plastics. This is discussed further below.

60

Chris S. Runion and Alfonso H. Lopez, “Recycled Materials Advantage Program,” Pub. L. No. Ch.

781, H. 1287 (2022), https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?ses=221&typ=bil&val=hb1287.

61

Voulvoulis et al., “Examining Material Evidence: The Carbon Footprint.”

62

Voulvoulis et al.

63

Voulvoulis et al.

64

Voulvoulis et al.

65

Voulvoulis et al.

66

Voulvoulis et al.

12

Congressional Action

Require a 30 by ’30 National Recycled Plastics Standard

To drive a consistent national approach to recycling and encourage the development of

efficient recycling systems, Congress should implement a national standard, requiring 30

percent recycled plastic in plastic packaging by 2030.

According to the U.S. EPA’s 2018 “Advancing Sustainable Materials Management” report,

only 9 percent or ~6 billion pounds of all plastics generated are currently collected for

recycling. In order to achieve the ambitious goal of 30 percent recycled plastic in all plastic

packaging by 2030, it is estimated that 13 billion pounds of recycled plastic material will

need to be produced every year according to an analysis conducted by the Independent

Commodity Intelligence Service (ICIS).

67

This is significantly more than the amount of

plastic currently collected for recycling. To bridge this gap and meet the 2030 goal, more

households will need access to recycling collection systems and significant enhancements

will need to be made to sorting systems as well as recycling infrastructure.

Mechanical recycling will need to continue to expand and new advanced recycling facilities

will need to be built for America to improve its recycling rate and increase the amount of

recycled plastic in packaging. ACC is committed to doing their part to address this

challenge. The industry has already announced many projects and initiatives to expand

advanced recycling capacity; however, more work is still required particularly in collection

and sorting to ensure these projects get the post-use plastics they need to be successful.

Rapidly scaling advanced recycling capacity will be essential to meet the target particularly

for food, medical and pharmaceutical grade packaging since advanced recycling produces

the virgin equivalent plastics these applications require. Supportive policies described

below to create a modern regulatory framework, national standards for plastics recycling

and sustainable financing for access and collection will greatly contribute to the

achievement of this goal.

Create a Modern Regulatory System to Develop a Circular Economy for Plastics

To create a circular economy for plastics, it is critical to better harmonize the nation’s

mechanical and advanced recycling efforts with existing state and international efforts,

which will help spur development of new recycling technologies and capacity. That is why

Congress should:

• Acknowledge the role of advanced recycling in creating a circular economy for plastic

packaging.

• Define advanced recycling as a manufacturing process and distinguishing it from

solid waste disposal.

• Recognize the ability of auditable third-party certification systems to verify

production of recycled plastics by applying mass balance attribution principles.

67

Prashanth Sabbineni, James Ray, and Paula Learnini, “INSIGHT: How the US Can Achieve High

Plastic Recycling Rates,” ICIS Explore (blog), July 6, 2021,

https://www.icis.com/explore/resources/news/2021/07/06/10660235/insight-how-the-us-can-achieve-

high-plastic-recycling-rates.

13

Thirty U.S. states still have outdated policies that could regulate advanced recycling as

“waste disposal” rather than manufacturing. Doing so sends entrepreneurs down the wrong

regulatory pathway for siting a facility, making it more difficult for companies to make

investments and deploy advanced recycling technologies. These technologies are essential

for companies that manufacture and sell consumer commodities, food and beverages to

reach the recommended 30% by ‘30 recycled plastics standard proposed in this document.

To date, 20 U.S. states have enacted legislation to create a more modernized regulatory

framework that paves the way for states to more effectively regulate these facilities as

manufacturing operations while simultaneously driving more investment into advanced

recycling facilities that transform hard-to-recycle plastics into new plastics and other high-

value materials and products.

Develop National Recycling Standards for Plastics

National recycling standards for plastics are needed to support a circular economy and help

achieve the EPA’s goal to increase the recycling rate to 50 percent by 2030. Current

localized differences in recycling practices and materials management creates confusion for

consumers and inefficient markets for recycled plastics. That committee should address:

To help overcome the inconsistencies among the more than 9,000 recycling jurisdictions,

Congress should empower the EPA and the DOE to bring together the plastics value chain

and municipalities to develop a set of national plastics recycling standards. A National

Plastics Recycling Standards Advisory Committee. That committee should address:

• Minimum household access standards to optimize the ability of Americans to

recycle.

• Minimum standards and best practices for consumer outreach, education and other

activities to increase the national recycling rate for all materials.

• Minimum infrastructure capacity standards to ensure jurisdictions can handle

common materials and adjust to new waste streams, including the development of

federal grant programs to assist with equitable access for all communities.

• Standards for municipal, state and federal government and industry data collection,

as well as metrics and reporting for reuse, recycling, composting, recovery and

disposal to help the EPA measure the national recycling rate and report against the

National Recycling Goal.

• Minimum processing requirements to increase the recycling of post-use plastics.

• The basic specifications needed for advanced recycling feedstocks to inform

consistent sorting and processing standards.

• Standards and data collection procedures to determine the annual supply of post-use

plastics available for advanced recycling feedstocks.

Based on the advice and consultation with the committee and other experts, the EPA and

the DOE will develop and implement the standards. As a large institution, the GSA could

play an important role in implementing the standards this committee suggests at federal

installations.

14

Study the Impact of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from all Material to Guide

Informed Policy

Public policy, especially on health, climate change and the environment, must be developed

based on data and science, not ideology. To guide Congress in its development of future

public policy on climate and material use, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) should

conduct a study on the comparative benefits, resource use, resource efficiency and carbon

impact across the full life cycle of materials, such as plastics, steel, aluminum, glass,

textiles, wood and paper. The study should cover raw material extraction, production,

transportation, packaging, use, disposal and all methods of materials recovery.

These findings should inform Congress, the EPA, the DOE and other agencies across the

federal government to further guide public policy on materials use and climate change. We

believe the study results will help inform sound, science-based decision making. Federal

policies should consider materials’ life cycle impacts, as well as contributions to optimizing

resources, conserving energy, preserving material and food and reducing greenhouse gas

emissions. The study will leverage NAS expertise and support its mission “to provide

independent, objective analysis and advice to the nation and conduct other activities to

solve complex problems and inform public policy decisions.”

Establish an American-Designed Producer Responsibility System

In many other parts of the world, producer responsibility systems that are financed and

directed by the private sector have helped support recycling access and collection. These

systems help generate a consistent supply of quality post-use materials for recycling.

Supply side policies such as this will be required to develop the infrastructure to collect and

process greater volumes of post-use plastics and other materials.

ACC supports an American-designed producer responsibility system for consumer

packaging that strengthens environmental protection and is dedicated to helping fund

infrastructure development. By fostering innovation and stimulating a competitive

marketplace, it will help implement critical components of a circular system. And it is

consistent with our Guiding Principles.

68

An American-designed producer responsibility system, prioritized to modernize and expand

access, collection, and consumer education, would help provide critical funding dedicated to

developing a more circular economy for consumer packaging. In addition, implementation of

clear national recycling standards that embrace all economic and environmentally

sustainable forms of advanced and mechanical recycling will be a critical enabler of any

producer responsibility system. A well-designed program and clear national standards

should provide the right incentives and disincentives to prevent litter, discourage

landfilling and encourage recycling aligned with the EPA Waste Management Hierarchy.

Conclusion

Choosing LCA-guided decision-making and incenting recycled plastics procurement are

better ways to foster a more circular economy. Such policies will help reduce the

68

Plastic Division, “5 Actions for Sustainable Change.”

15

consumption of finite resources and the production of waste and can help mitigate

greenhouse gas emissions.

Plastics companies are working to drive growth of this circular economy, but smart policies

are needed to accelerate progress. Creating a circular economy for plastics will help our

nation:

• Reduce the amount of used plastics going to landfills, incinerators, and oceans;

• Drive actions to combat climate change;

• Improve recycling rates;

• Conserve natural resources;

• Develop a more robust and competitive recycling market; and

• Support and increase domestic jobs.

Plastics contribute immensely to sustainability and play a central role in combating climate

change. Again, thank you for allowing us to submit these comments for consideration.

(End)

16

References

Advisory Committee on Packaging. “Packaging in Perspective.” Industry report. Packaging

Federation, October 2008. https://www.thefactsabout.co.uk/file.php?fileid=28.

Bukowski, Todd, and Michael Richmond. “A Holistic View of the Role of Flexible Packaging

in a Sustainable World.” Industry report. Flexible Packaging Association, April 9,

2018. https://perfectpackaging.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/FPA-Holistic-View-of-

Sustainable-Packaging.pdf.

Elkington, John. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business.

Oxford, U.K.: Capstone, 1999.

Exec. Order No. 17 Recognizing the Value of Recycling and Waste Reduction, Pub. L. No.

E.O. 17 (2022).

https://www.governor.virginia.gov/media/governorvirginiagov/governor-of-

virginia/pdf/eo/EO-17-Recognizing-The-Value-of-Recycling-and-Waste-Reduction.pdf.

Exec. Order No. 77, Vol. 37, Iss. 17 Va. Reg. Regs. § (2021).

http://register.dls.virginia.gov/vol37/iss17/v37i17.pdf.

Exec. Order No. 13990 Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring

Science To Tackle the Climate Crisis, 86 F.R. § 14 (2021).

https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2021-01765.

Exec. Order No. 14008, Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, 86 F.R. § 19

(2021). https://www.regulations.gov/document/EPA-HQ-OPPT-2021-0202-0012.

Exec. Order. No. 14057, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal

Sustainability, 86 F.R. § 236 (2021). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-

12-13/pdf/2021-27114.pdf.

Feber, David, Stefan Helmcke, Thomas Hundertmark, Chris Musso, Wen Jie Ong, Jonas

Oxgaard, and Jeremy Wallach. “Climate Impact of Plastics.” Industry report.

McKinsey & Company, July 2022.

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/chemicals/our-insights/Climate-impact-of-

plastics.

Food & Agriculture Organization. “Food Wastage Footprint & Climate Change.” Fact sheet.

United Nations, November 2015. https://www.fao.org/3/bb144e/bb144e.pdf.

Green, Kenneth P. “Canada’s Wasteful Plan to Regulate Plastic Waste,” 2022.

https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/canadas-wasteful-plan-to-regulate-

plastic-waste.pdf.

International Society of Professional Sustainability Professionals. ISSP-SA Study Guide.

1st Ed. Portland, OR, 2016.

Jolliet, Olivier, Myriam Saade-Sbeih, Shanna Shaked, Alexandre Jolliet, and Pierre

Crettaz. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment. CRC Press, 2015.

https://doi.org/10.1201/b19138.

Lord, Richard. “Plastics and Sustainability: A Valuation of Environmental Benefits, Costs,

and Opportunities for Continuous Improvement.” American Chemistry Council, July

2016. https://www.plasticpackagingfacts.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ACC-

report-July-2016.pdf.

MB Public Affairs, Inc. “Fiscal Impacts of Prohibiting Expanded Polystyrene Food Service

Products in Maryland: SB 186 & HB 229.” Industry report, 2017.

https://www.plasticfoodservicefacts.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Maryland-2017-

fiscal-impact-study-of-SB-186-and-HB-229.pdf.

———. “Initial Comments on Virginia Executive Order Number 77 (2021),” April 4, 2021.

17

Mullan, Michael. “Science and Technology of Modified Atmosphere Packaging.” Dairy

Science, January 2011. https://www.dairyscience.info/index.php/packaging/117-

modified-atmosphere-packaging.html.

Ooraikul, B., and M. E. Stiles, eds. Modified Atmosphere Packaging Of Food. Boston, MA:

Springer US, 1995. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-2117-4.

Plastic Division. “5 Actions for Sustainable Change.” Industry report. Washington, D.C.:

American Chemistry Council, 2021.

https://www.plasticmakers.org/files/d6b3a34b9a88b1a6ee4da0a73b24562d740f80e4.

pdf.

Plastics Division. “U.S. Plastics Resin Producers Set Circular Economy Goals to Recycle or

Recover 100% of Plastic Packaging by 2040.” Media release. American Chemistry

Council, May 9, 2018. https://www.americanchemistry.com/chemistry-in-

america/news-trends/press-release/2018/us-plastics-resin-producers-set-circular-

economy-goals-to-recycle-or-recover-100-of-plastic-packaging-by-2040.

Runion, Chris S., and Alfonso H. Lopez. Recycled Materials Advantage Program, Pub. L.

No. Ch. 781, H. 1287 (2022). https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-

bin/legp604.exe?ses=221&typ=bil&val=hb1287.

Sabbineni, Prashanth, James Ray, and Paula Learnini. “INSIGHT: How the US Can

Achieve High Plastic Recycling Rates.” ICIS Explore (blog), July 6, 2021.

https://www.icis.com/explore/resources/news/2021/07/06/10660235/insight-how-the-

us-can-achieve-high-plastic-recycling-rates.

Slaper, Timothy F., and Tanya J. Hall. “The Triple Bottom Line: What Is It and How Does

It Work?” Indiana Business Review 86, no. 1 (2011): 4–8.

Tsiamis, Demetra A., Melissa Torres, and Marco J. Castaldi. “Role of Plastics in Decoupling

Municipal Solid Waste and Economic Growth in the U.S.” Waste Management 77

(July 2018): 147–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.05.003.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “National Overview: Facts and Figures on

Materials, Wastes and Recycling,” October 2, 2017. https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-

figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/national-overview-facts-and-figures-

materials.

Voulvoulis, N., R. Kirkman, T. Giakoumis, P. Metivier, C. Kyle, and V. Midgley.

“Examining Material Evidence: The Carbon Footprint.” Imperial College London,

2020. https://www.americanchemistry.com/better-policy-

regulation/plastics/resources/examining-material-evidence-the-carbon-fingerprint.

18

Table 1

Responses to GSA Posed Questions

GSA Question

ACC Response

Part III. Request for public feedback

1. What is your role in your product’s

supply chain? Are you a manufacturer,

distributor, reseller, or other (comments

are encouraged from any impacted parties

including local municipalities and

economically and/or disadvantaged

communities)?

The American Chemistry Council (ACC) is

a membership-based trade association. The

Plastics Division of ACC represents the

leading manufacturers of plastics and other

companies throughout the entire plastics

value chain. (See, Footnotes 5 and 6 above.)

2. Does your company have control over the

methodology in which your product is

packaged for shipment?

Not applicable.

3. What are the differences between a

paper based, aluminum based, or

compostable packaging and a single-use

plastic based packaging?

See responses to (a) and (b) below.

a. What are the performance

differences?

Generally, use of plastic in products and

packaging results in decreased GHG

emissions than common plastic

alternatives. (See, Environmental Impacts

on page 4).

b. What are the cost differences?

Generally, plastic packaging costs less than

plastic alternatives. (See, Increased Public

Costs on page 8)

4. Does your company have experience

using environmentally preferable

packaging?

GSA decision-making should be guided by

life cycle assessments. (See, Environmental

Impacts on page 4) and

GSA should not presume that plastic

alternatives are always environmentally

preferable. (See, Environmental Impacts on

page 4).

a. If an environmentally preferable

option was utilized, what benefits

did your company experience from

such a change?

b. What is the relationship between

your packaging and your product

branding?

c. Will packaging be considered as

part of your company’s climate

financial disclosure, if applicable?

5. What is the best way for GSA to aid its

contractors in moving to environmentally

preferable packing and packaging? How

quickly should it move?

6. Are there any market, regulatory,

statutory or cost barriers to selecting

environmentally preferable packaging such

Question 6 to 9 assumes that plastic

alternatives are always environmentally

19

GSA Question

ACC Response

as paper based or biodegradable

packaging?

If yes, please specify what the barrier is

and what is creating the barrier (i.e., the

product’s casing or the shipment

packaging).

preferable. This is not the case. (See,

Environmental Impacts on page 4).

Instead, GSA decision-making should be

guided by life cycle assessments. (See,

Environmental Impacts on page 4 and LCA

Guided Decision-making on page 11.)

In addition to LCA guided decision-making,

GSA should also consider incenting

recycled plastics content procurement. (See,

Incent Recycled Content on page 10.)

7. What should be considered when

developing a timeline to implement

regulatory changes in reducing single use

plastic as either the primary product, or as

the packaging material?

8. Which, if any, single use plastic items

GSA should choose not to contract for

through its federal supply schedules? Are

there exceptions GSA should make to

ensure no harm to customer agency

missions?

9. How could compliance with reduced or

eliminated plastic content be verified?

a. How can GSA and industry take

advantage of innovative

technologies or business practices to

improve accuracy of verification

while minimizing the administrative

burden on companies?

b. Are there private sector

standards, ecolabels, and/or

certifications your company is using

to meet environmentally preferred

packaging goals?

IV Request for economic data and consumer research

1. What will the estimated cost be to

change, reduce, or eliminate single-use

plastic from your product lines?

Questions 1 to 4 assumes that plastic

alternatives will cost less. This is not likely

the case. (See, Increased Public Costs on

page 8).

2. What will the estimated costs be to

change, reduce, or eliminate single-use

plastic packaging?

3. Will a change from single-use plastic

packaging result in a reduced cost in

freight?

4. What reporting or monitoring standards,

if any, exist to track the use of more

environmentally preferable packaging

material?

GSA decision-making should be guided by

life cycle assessments. (See, LCA Guided

Decision-making on page 11.)

20

GSA Question

ACC Response

5. What is the liability risk of any of the

purchased goods being damaged if

packaging is reduced or changed?

GSA decision-making should be guided by

life cycle assessments. (See, Environmental

Impacts on page 4 and LCA Guided

Decision-making on page 11.) A properly

constructed LCA will also consider product

loss.

6. What other identifiable risks are posed

to industry, the government, and overall

economy if packaging is reduced or

changed?

In these comments, ACC has raised

environmental, public costs, and scope

concerns. ACC reserves the right to raise

further concerns. (See, Introduction on page

3.)

Additionally, GSA should consider the

topics of the ANPR through a framework

such as the triple bottom line (TBL).

69

When calculating the TBL, multiple

measures and variables should be

included.

70

69

John Elkington, Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business (Oxford,

U.K.: Capstone, 1999).

70

Timothy F. Slaper and Tanya J. Hall, “The Triple Bottom Line: What Is It and How Does It

Work?,” Indiana Business Review 86, no. 1 (2011): 4–8.

21

Table 2

Selected Presidential Polices, Effect of ANPR, and ACC Suggestions

Executive Order

ANPR

ACC Suggestion

Procurement. The national

climate change resilience

strategies include federal

procurement.

71

GSA should

prioritize climate action in

procurement.

72

The ANPR would likely

lead to reducing plastic

procurement and lead to (1)

alternatives with a higher

GHG emissions, and (2)

increased food waste

resulting in increased

methane emissions all at

increased costs.

LCA based decisions.

Base procurement

decisions based on

lifecycle analysis will

help ensure science-

based climate decisions.

Federal GHG Reduction.

Scope 1, 2, and 3 greenhouse

gas emissions must be reduced

by federal agencies.

73

Science-driven decision-

making. Agency decision

making must be guided by the

full costs of greenhouse gas

emissions.

74

This recognizes the

breadth of climate impacts and

includes the social cost of

methane.

75

Climate decisions

should be driven by science.

76

At this stage, the ANPR

seems to assume that

plastics are never

environmentally preferable.

This is not supported by the

evidence.

Circular economy. Federal

agencies must (1) minimize

waste, (2) support markets for

recycled products, (3) promote a

circular economy,

77

and (4)

divert at least 50 percent of

The ANPR would like lead

to (1) increased waste

because alternatives tend to

weigh more, (2) no

additional support for

recycled content, (3) a

“procurement ban” is not

consistent with a circular

Recycled plastics

preference. Create a

purchasing preference

for items containing

recycled plastics. This

will help: (1) reduce

landfilling pressure, (2)

create a market for

71

Exec. Order. No. 14057, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal

Sustainability.

72

Exec. Order No. 14008, Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad.

73

Exec. Order. No. 14057, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal

Sustainability; Exec. Order No. 13990 Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring

Science To Tackle the Climate Crisis.

74

Exec. Order No. 13990 Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science To

Tackle the Climate Crisis.

75

Exec. Order No. 13990 Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science To

Tackle the Climate Crisis.

76

Exec. Order No. 14008, Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad; Exec. Order No. 13990

Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science To Tackle the Climate Crisis.

77

“Save Our Seas 2.0 Act” Sec 2.: “The term ‘‘circular economy’’ means an economy that uses a

systems-focused approach and involves industrial processes and economic activities that(A) are

restorative or regenerative by design; (B) enable resources used in such processes and activities to

maintain their highest values for as long as possible; and (C) aim for the elimination of waste through

the superior design of materials, products, and systems (including business models).”

22

nonhazardous waste, including

food.

78

economy approach, (4) it is

unclear how waste

diversion will be achieved

when purchasing heaver

alternatives.

recycled plastic, (3) take

an approach consistent

with the circular

economy, and (4)

recycled content will

help support landfill

diversion.

Note. Additionally, Congress should (1) require a 30 by ’30 national recycled plastics

standard, (2) create a modern regulatory system to develop a circular economy for plastics,

(3) develop national recycling standards for plastics, (4) study the impact of greenhouse gas

emissions from all material to guide informed policy, and (5) support an American-designed

producer responsibility system.

79

(See, Congressional Action on page 12).

78

Exec. Order. No. 14057, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal

Sustainability.

79

Plastic Division, “5 Actions for Sustainable Change.”

23

Figure 1

Effects of Current ANPR and ACC Suggested Policy

Note. Additionally, Congress should (1) require a 30 by ’30 national recycled plastics

standard, (2) create a modern regulatory system to develop a circular economy for plastics,

(3) develop national recycling standards for plastics, (4) study the impact of greenhouse gas

emissions from all material to guide informed policy, and (5) support an American-designed

producer responsibility system.

ANPR Effect

•(-) Plastic

•(+)

Alternatives

Environemental

Impact

•(+) GHG emissions

•(+) Landfilling

Current

ANPR

Policy Effect

•(+) Recycled

plastics

•(+) Sustainable

decisionmaking

Environemental

Impact

•(-) GHG emissions

•(-) Landfilling

ACC

•(+) LCA

decisionmaking

•(+) Incent

recycled plastics