Regulatory approaches to

international labour recruitment in

Canada

Policy Research, Research and Evaluation Branch

Leanne Dixon-Perera

June 2020

The opinions expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect

the views of the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship or the Government of

Canada.

For information about other Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) publications,

visit: www.canada.ca/ircc-publications

.

Également disponible en français sous le titre : Approches réglementaires pour le recrutement

de la main d’œuvre internationale au Canada

Visit us online

Immigration Refugees and Citizenship Canada website at www.Canada.ca

Facebook at www.facebook.com/CitCanada

YouTube at www.youtube.com/CitImmCanada

Twitter at @CitImmCanada

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Immigration,

Refugees and Citizenship, 2020.

Ci4-216/2021E-PDF

978-0-660-37201-3

Project reference number: R39-2019

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abbreviations and acronyms 5

Key terms 6

Introduction 7

Context 8

International labour recruitment and unfair practices 8

Temporary labour migration to Canada 8

Legislative and jurisdictional landscape 11

Comparative discussion of regulatory approaches 17

1. Laws that apply to all 19

Provincial overview 23

Alberta – Employment Agency Business Licensing Regulation 23

Ontario – Employment Protection for Foreign Nationals Act 24

Saskatchewan – Foreign Worker Recruitment and Immigration Services Act 25

British Columbia – Temporary Foreign Worker Protection Act 26

Nova Scotia – Labour Standards Code 26

New Brunswick – Employment Standards Act 27

Manitoba – Worker Recruitment and Protection Act 28

Quebec – Regulation respecting personnel placement agencies and recruitment agencies for

temporary foreign workers 29

2. No recruitment fees to workers 30

What constitutes recruitment fees and related costs? 30

Prohibitions on charging recruitment fees 32

Prohibition on employer recovery of costs 35

3. Licensing and registration 37

Recruiter licensing 37

Employer registration 43

4. Freedom of movement 47

Right to identity documents 47

Prohibition against threatening deportation 49

5. Freedom from deception or coercion 50

Prohibited and unfair practices 50

Consent through signed and written contract or agreement 52

6. Access to information 53

Information on rights document 53

Disclosure and declaration document 54

7. Access to grievance mechanisms 55

Barriers to accessing rights and recourse 55

What is the complaint process? 57

8. Effective enforcement 61

Proactive and reactive inspections 61

Administrative consequences and penal sanctions 61

Operational challenges 63

Conclusion: An uneven patchwork of protections 64

Appendix I: Work permit statistics 65

Appendix II: Relevant international norms on fair recruitment 70

Appendix III: Select provincial reference documents 76

4

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Provincial regulation of employment/recruitment of migrant workers 15

Table 2: To whom does the relevant legislation apply? 19

Table 3: Which migrant workers are covered by relevant provincial legislation: how are they defined? 21

Table 4: Exemptions to employer registration requirements 22

Table 5: Exemptions to recruiter licensing requirements 22

Table 6: Comparison of licensing process for recruiters by province 42

Table 7: Comparison of licence characteristics by province 43

Table 8: Comparison of registration process for employers by province 46

Table 9: Complaint time limit by province 58

Table 10: Potential criminal sanctions 62

Table 11: Work permit holders* signed in 2018, by province, program** and work permit type*** 65

Table 12: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) work permit holders signed in 2018, by province and

NOC skill level 66

Table 13: International Mobility Program (IMP) employer-specific work permit holders signed in 2018, by

province and NOC skill level 68

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Work permit holders signed by province and territory in 2018 10

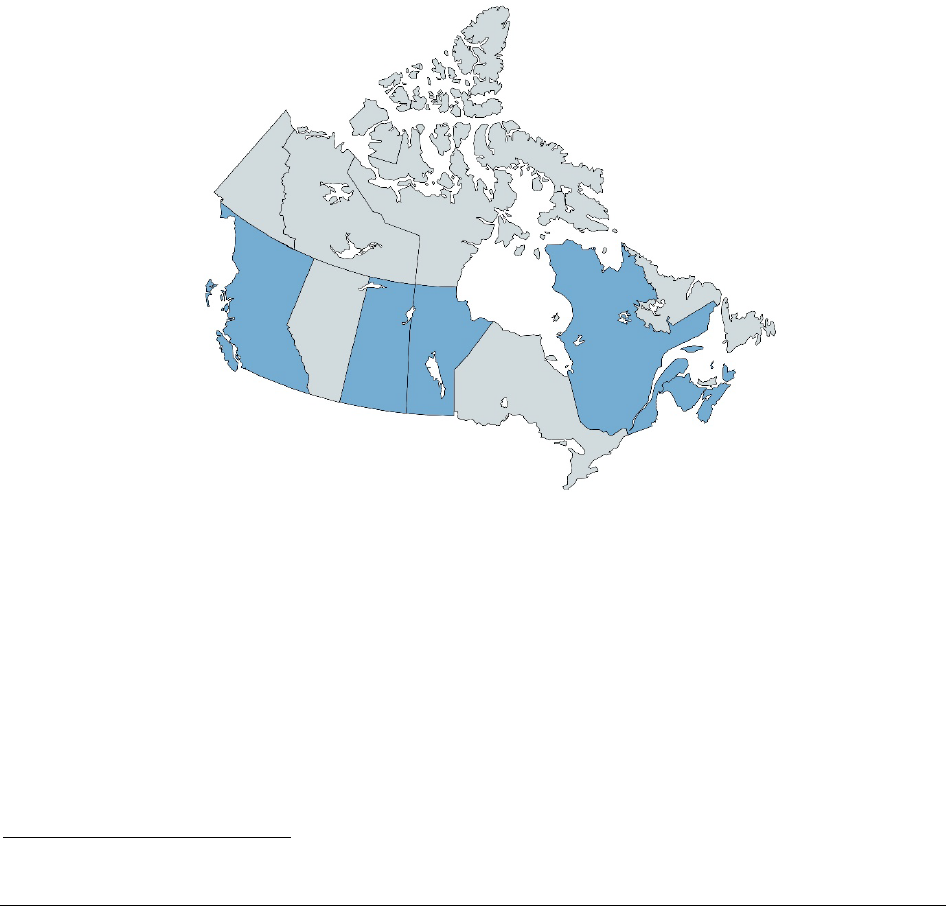

Figure 2: Provinces with migrant worker employment and/or recruitment law 14

Figure 3: Timing of coming into force of relevant provincial regulation 14

Figure 4: Fair recruitment principles 18

Figure 5: Migrant worker population and provincial scope 20

Figure 6: Recruiter licensing map 37

Figure 7: Number of recruiter licenses listed online (as of February 2020) 40

Figure 8: Labour recruitment supply chain models 41

Figure 9: Employer registration map 44

Figure 10: Summary of barriers to accessing justice for migrant workers 56

Figure 11: Excerpt from Ontario’s EPFNA Claim Form – Claims again recruiter 57

Figure 12: Complaint time limits by province 58

5

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

Alta. Alberta

B.C. British Columbia

CAQ Certificat d’acceptation du Québec (Quebec Acceptance Certificate)

CNESST Commission des normes, de l’équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail

EABLR Employment Agency Business Licensing Regulation (Alberta)

ESDC Employment and Social Development Canada

ESA Employment Standards Act (New Brunswick)

LMIA Labour Market Impact Assessment

EPFNA Employment Protection for Foreign Nationals Act (Ontario)

F.A.R.M.S. Foreign Agricultural Resource Management Services

F.E.R.M.E. Fondation des Entreprises en Recrutement de Main-d’œuvre agricole Étrangère

FWRISA Foreign Worker Recruitment and Immigration Services Act (Saskatchewan)

GCM Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration

IOM International Organization for Migration

IRPA Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

IRPR Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulation

ICCRC Immigration Consultants of Canada Regulatory Council

IRCC Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

ILO International Labour Organization

IMP International Mobility Program

LSC Labour Standards Code (Nova Scotia)

Man. Manitoba

NOC National Occupational Classification

N.B. New Brunswick

N.S. Nova Scotia

Ont. Ontario

PNP Provincial Nominee Program

Que. Quebec

Sask. Saskatchewan

SAWP Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program

TFWP Temporary Foreign Worker Program

TFWPA Temporary Foreign Worker Protection Act (British Columbia)

WRAPA Worker Recruitment and Protection Act (Manitoba)

6

KEY TERMS

In this paper, the following definitions are employed:

Employer: a person or an entity that engages employees or workers, more specifically, migrant

workers.

Foreign national: a person who is not a Canadian citizen or a permanent resident in Canada.

Labour recruiter: private employment agencies and all other third-party intermediaries that

offer labour recruitment and placement services. Can be formal (operate within regulatory

framework) and informal (unregulated). Other terms used to describe this group include

recruitment agencies, consultants, brokers, and sub-agents.

Labour recruitment: involves the advertising, information dissemination, selection, transport,

and placement of migrant workers into employment and return to the country of origin where

applicable. This applies to both jobseekers and those in an employment relationship.

Migrant worker: any foreign national who migrates to Canada and is working or seeking

employment in Canada. Terms such as foreign worker, temporary foreign worker, labour

migrant, and migrant worker are generally used interchangeably in the Canadian context.

Temporary labour migration programs: the programs under which migrant workers are

authorized to enter and work. In Canada, the two main programs are called the Temporary

Foreign Worker Program and the International Mobility Program.

7

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, provincial governments in Canada have significantly changed the statutory

landscape under which labour recruiters and employers of migrant workers operate. Regulatory

approaches were developed largely in response to increased volumes of migrant workers and the

reported recruitment-related abuse and exploitation that workers can be exposed to in order to

come to Canada. In fact, nearly 500,000 work permits were issued nationwide in 2018, an

increase of over 50 percent since 2008. The unethical conduct of labour recruiters, including

charging migrant workers exorbitant fees to work in Canada has also been documented alongside

this growth.

As such, this paper is intended to be a resource on the provincial statutory regulation of

international labour recruitment and employment in Canada. In order to frame the comparative

discussion, select international principles on fair recruitment are used as a thematic framework.

The following questions guided the research:

− What are the provincial approaches to regulating international labour recruitment and

employment of migrant workers in Canada? How do they compare against international fair

recruitment norms?

− What is the coverage and application of these laws over migrant workers? How are migrant

workers and their employers and labour recruiters defined?

− How are labour recruiters and employers regulated? Is licensing or registration required?

− What protective measures are in place for migrant workers at risk of exploitative or abusive

recruitment or employment practices?

− Given the transnational nature of migrant labour recruitment and employment, how is

federal immigration law and policy implicated in these provincial approaches?

With these questions in mind, an empirical review of relevant statutory regulation (i.e., the relevant

laws enacted by legislative bodies and enforced by government) in eight Canadian provinces was

undertaken. A desk-based review of pertinent statutes, regulations, and grey material, including

interpretation manuals, guidelines, and forms, was conducted between August 2019 and January

2020. Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) work permit data was examined for

descriptive analysis and context. International standards and reports on labour migration, migrant

worker protection, fair and ethical labour recruitment, and human trafficking were also reviewed in

order to develop the overarching framework under which the relevant regulatory approaches are

compared. Secondary research was supplemented with semi-structured interviews with provincial

government administrators over the same time period, including both policy and operational

officials to validate and clarify technical aspects of their respective regimes.

1

This paper focuses on what relevant laws are in place and what they ought to do. No conclusions

are drawn with respect to the effectiveness of enforcement of any regulatory framework (e.g., no

enforcement gaps are identified) as it is outside of the scope of this review. In addition, non-

regulatory provincial activities promoting ethical international labour recruitment are not explored.

2

1

In-person meetings with officials from each province were conducted, except Quebec’s Commission des normes, de l’équité, de

la santé et de la sécurité (CNESST) du travail due to timing of research schedule and CNESST final regulatory amendments.

Technical questions were accordingly addressed electronically.

2

Non-regulatory activities can include how provincial immigration or employment authorities conduct their own recruitment

activities, by either facilitating or assisting employers to directly recruit migrant workers, or any provincial participation in

international ethical recruitment initiatives like the International Organization for Migration’s (IOM)

International Recruitment

Integrity System (IRIS).

8

CONTEXT

I

NTERNATIONAL LABOUR RECRUITMENT AND UNFAIR PRACTICES

The international labour recruitment landscape is complex. Private labour recruiters and

employment agencies in countries of origin and destination operate as intermediaries between

employers and migrant workers; relationships between them often span multiple jurisdictions and

long periods of time. The basic business model of the recruitment industry is to actively seek out

clients, both workers and employers, establish matches, and charge one or both parties for these

services. Some recruiters may provide additional services for extra fees, such as arranging

transportation and loans, providing orientation for workers before departure or after arrival,

filling visa, work permit or immigration forms, or supplying language or technical training.

As such, labour recruiters, both formal (regulated) and informal (unregulated), play a critical role

in matching local labour demand with international labour supply, leveraging global networks of

brokers, sub-agents, and travel and immigration expertise. Prospective migrant workers may

naturally come to depend on recruiters in order to navigate the process and ultimately enter and

become employed in another country.

This dependence, however, can create abusive or exploitative conditions for workers if recruiters

act unfairly or unethically with the intention of deceiving prospective migrant workers into

fraudulent employment and/or immigration opportunities. For example, by misrepresenting

working conditions in employment contracts, or coercing migrants into illegal or illegitimate

work arrangements. International labour recruitment is a lucrative business: recruiters have many

touchpoints to charge fees for multiple services that are sometimes unnecessary or excessive.

Furthermore, unfair recruitment activity can put migrant workers at higher risk of being subjected

to forced labour or human trafficking. If on a spectrum or continuum, fair and ethical recruitment

practices would be at one end with forced labour and human trafficking at the other. The broad

range of abusive and unfair recruitment practices fall in the somewhat grey area between them.

Unfair recruitment practices:

• Charging fees, often exorbitantly high fees, to workers

• Coercing worker into taking a contract with less generous conditions than what was originally signed

(i.e., contract substitution)

• Advertising non-existent jobs

• Misrepresentation about terms and conditions of employment contract or immigration prospects

• Illegal wage recovery and financial abuse where agents or employers deduct recruitment fees or costs

from wages once in destination country

• Threats and intimidation including psychological and verbal abuse

• Confiscation of passport, work permit or other identity documents

TEMPORARY LABOUR MIGRATION TO CANADA

In Canada, migrant workers play an important role in local society, culture, and the economy.

Their contributions are diverse and significant: migrants are hired to do everything from

harvesting fruits and vegetables, caring for children and the elderly, driving long-haul transport

trucks, to working in software engineering, academia, and medicine.

In order to come to Canada, a migrant worker must be authorized to work under one of two

temporary labour migration programs: the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) or the

9

International Mobility Program (IMP). The main distinction between the TFWP and IMP is the

employer requirement or exemption from a labour market test, called the Labour Market Impact

Assessment (LMIA). The LMIA serves to verify a number of factors, primarily if a Canadian is

available to do the job. All work authorizations under the TFWP require an LMIA and employers

may be refused if the assessment finds a negative impact on the labour market. Migrant workers

under the TFWP commonly include, but are not limited to, agricultural and domestic (caregiver)

workers.

Under the IMP, employers are not required to seek an LMIA before issuing an offer of

employment due to a recognition that in certain circumstances, broader benefits to Canada from

hiring the worker may outweigh the requirement for the assessment, such as potential impacts on

the labour market. Migrant workers under the IMP include workers covered under international

trade agreements, youth taking part in working holiday exchanges, postgraduate international

students, and charitable and religious workers, among many others.

All work authorizations under the TFWP are

granted through the issuance of work permits

conditional to one employer and employment

offer, also called “employer-specific” or

“closed” work permits. The IMP facilitates

both employer-specific and open work

permits, as well as work permit exemptions.

3

Open work permits allow migrant workers to

change employers during the validity period

prescribed on the work permit.

Most work permits (~70%) issued in 2018 were under the IMP. Unauthorized or irregular work

performed by migrants, by its very nature, is not readily captured by IRCC data.

Regionally, migrant workers are unevenly dispersed across Canada, the majority (~75%) are in

the most populated provinces of Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia. A detailed breakdown

of provincial work permit data is captured in Appendix I.

In terms of how migrant workers are recruited to Canada, the contemporary landscape primarily

involves the operation of private international labour recruiters and employment agencies. A

notable exception is the recruitment of migrant farm workers under the Seasonal Agricultural

Worker Program (SAWP) whereby labour departments in the country of origin (Mexico and the

Commonwealth Caribbean) and non-profit agencies in Canada like Foreign Agricultural

Resource Management Services (F.A.R.M.S.) or Fondation des Entreprises en Recrutement de

Main-d’œuvre agricole étrangère (F.E.R.M.E.) which organize and administer formal recruitment

activities.

4

The exact proportion of migrant workers seeking employment in Canada through a

private labour recruiter is unknown. However, a small but growing body of relevant research has

identified a proliferation of the private “migration industry”, which has grown alongside migrant

worker volumes under temporary labour migration streams in recent years.

5

Indeed, the last

3

Work authorizations without a work permit (work permit exemptions) are not captured by IRCC data; this includes work permit

exemptions under section 186 of the IRPR for study permit holders, athletes, and clergy, among others.

4

F.A.R.M.S. and F.E.R.M.E. both operate on behalf of groups of employers.

5

See Zell, S. (2018). Outsourcing the border: recruiters and sovereign power in labour migration to Canada. (PhD Dissertation,

University of British Columbia); Gesualdi-Fecteau, D., Thibault, A., Schivone, N., Dufour, C., Gouin, S., Monjean, N., & Moses, E.

(2017) A story of debt and broken promises: The recruitment of Guatemalan migrant workers in Quebec. Revue québécoise de

droit international 30, 95; Rodgers, A. E. (2016). Temporary foreign workers in British Columbia: Unfree labour and the rise of

unscrupulous recruitment practices. (Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University); Muir, G. (2015). Unmapping recruitment: An

Program LMIA

Work

authorization type

Work permit

type

TFWP Required Work permit

Employer-

specific

IMP Exempt

Work permit

OR work permit

exempt

Employer-

specific

OR open

10

decade has seen an increase of over 50 percent in work permit issuance: around 495,000 work

permits were issued in 2018, while closer to 328,000 were issued in 2008. Relevant research has

uncovered abusive recruitment practices, including illegal fee charging and the advertisement of

non-existent jobs across Canada. During this period, public concerns have also been raised

regarding the role of unscrupulous recruiters as it continues to be scrutinized in the media.

6

Figure 1: Work permit holders signed by province and territory in 2018

Note: About 10% of all work permits issued in 2018 are not captured as they did list an intended location.

To deter and enforce consequences on unscrupulous international labour recruiters, a number of

provinces in Canada have regulated the industry in their respective jurisdictions over the last ten

years. In some cases, they have also placed additional requirements on employers of migrant

workers, in tandem or separate from labour recruiter provisions. To position the analysis of these

regulatory approaches, a brief discussion of the legal and jurisdictional landscape that oversees

immigration, employment, and recruitment in Canada is provided below.

exploration of Canada's Temporary Foreign Worker Program in Guatemala. (Master’s Thesis, Concordia University); Faraday, F.

(2014). Profiting from the precarious: How recruitment practices exploit migrant workers: Toronto: Metcalf Foundation; Choudry,

A., & Henaway, M. (2012). Agents of misfortune: Contextualizing migrant and immigrant workers' struggles against temporary

labour recruitment agencies. Labour, Capital and Society, 36-65; Fudge, J. (2011). Global care chains, employment agencies,

and the conundrum of jurisdiction: Decent work for domestic workers in Canada. Canadian Journal of Women and the Law 23:1,

pp. 235–264; Parrott, D. (2011). The role and regulation of private, for-profit employment agencies in the British Columbia labour

market and the recruitment of temporary foreign workers. (Master’s Thesis, University of Victoria).

6

Select media sources include: Tomlinson, Kathy. False promises: Foreign workers are falling prey to a sprawling web of labour

trafficking in Canada. The Globe and Mail. 5 April 2019; Rankin, Jim. Unscrupulous recruiters keep migrant workers in ‘debt

bondage.’ The Toronto Star, 8 October 2017.

11

LEGISLATIVE AND JURISDICTIONAL LANDSCAPE

Immigration-employment nexus

Conventional employment relationships in Canada are bilateral in nature: an employment

contract results from the consent of the employer and employee. The rights and obligations of

these parties is determined by labour or employment law which for the most part is under sub-

national (provincial) jurisdiction. However, the relationship between a migrant worker employee

and their employer is more complex. Labour laws coexist with national (federal) immigration

laws which govern the administration of the temporary labour migration program under which

migrant workers enter and are authorized to work in Canada. It is the nexus of these distinct

regulatory frameworks, involving different rules and enforcement actors that creates a unique

relationship between a migrant worker and their employer. What is more, an understanding of

this relationship is incomplete without an appreciation of the mediating practices that facilitate

and constrain it: the brokerage between migrant workers and employers. Capturing labour

brokers, or recruiters, and if and how the recruitment business is regulated is thus crucial in

discerning these unique employment relationships.

The linkage between these regulatory frameworks: immigration, employment and recruitment, is

raised a number of times throughout this paper’s discussion, and as such marked by a

mangrove tree to signify the complex web of roots connecting them.

To position the landscape involved in this nexus, the following sections offer an overview of the

somewhat complex national and sub-national regulatory activities that oversee migrant worker

employment and recruitment in Canada.

National

The responsibilities of the federal and provincial governments are defined in the Constitution Act,

1867.

7

Canada and the provinces share jurisdiction over immigration, though the federal

government alone administers temporary labour migration programs under the Immigration and

Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and its Regulations (IRPR).

8

The IRPR facilitates the authorization of foreign nationals to enter and work in Canada. Sections

200 to 208 of the IRPR provide the regulatory authorities for which officers may issue work

permits, and in so doing, they constitute the basis for the two temporary labour migration

programs – the TFWP and IMP.

9

These programs are jointly administered by Immigration,

Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), Employment and Social Development Canada

(ESDC), and the Canada Border Services Agency.

The IRPR does not directly regulate international labour recruiters or employment agencies (i.e.,

the third-party recruitment process of migrant workers), but it does impose recruitment-related

requirements indirectly on employers of migrant workers through compliance mechanisms,

discussed below. That being said, labour recruiters are captured by section 91 of the IRPA if they

also provide immigration services; it requires them to be members in good standing of a

provincial law society or the Immigration Consultants of Canada Regulatory Council (ICCRC) in

7

The Constitution Act, 1867, 30 & 31 Vict, c 3.

8

Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, SC 2001, c 27; Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, SOR/2002-227.

9

These regulatory authorities include labour market assessments (s. 203), international agreement or arrangements (s. 204),

Canadian interests (s. 205), no other means of support (s. 206), applicants in Canada (s. 207), vulnerable workers (s. 207.1), and

humanitarian reasons (s. 208).

12

order to provide immigration advice.

10

In addition, any activities of labour recruiters that

constitute human trafficking are captured under section 118 of the IRPA which makes it a

criminal offence to use abduction, fraud, deception or the use or threat of force or coercion to

recruit and/or bring people to Canada. Under Ministerial Instructions pursuant to subsection 24(3)

of the IRPA, officers may also issue temporary resident permits to foreign nationals who are

victims of trafficking in persons.

Compliance mechanisms

The IRPR has both front-end and back-end compliance measures over employer-specific work

permits. About 33 percent of the total work permit holders signed in 2018 were on employer-

specific work permits and thus covered by these measures.

When an employer-specific work permit or LMIA application is being processed by IRCC or

ESDC respectively, officers must assess the genuineness of the offer of employment, pursuant to

factors listed in subsection 200(5) of the IRPR. This is a front-end compliance mechanism and a

negative assessment of genuineness would result in a refusal. Factors to consider include

whether:

− the offer is made by an employer actively engaged in the business for which the offer was

made;

− the offer is consistent with the reasonable employment needs of the employer;

− the terms of the offer are terms that the employer is reasonably able to fulfil; and

− the past compliance of the employer, or any person who recruited the foreign national for

the employer, with the federal or provincial laws that regulate employment or the recruiting

of employees.

For example, if it became known during the processing of a work permit application for a job

offer in Alberta that the applicant paid illegal recruitment fees, contrary to provincial legislation,

this could constitute grounds for the work permit refusal (i.e., related to “past compliance of any

person who recruited the foreign national”).

In terms of back-end compliance measures, sections 209.1 to 209.997 of the IRPR impose

conditions on employers who hire migrant workers on employer-specific work permits and

provide authorities for employer inspections and administrative consequences in case of non-

compliance (warning letters, monetary penalties, and/or bans on hiring migrant workers). These

provisions constitute the TFWP and IMP employer compliance regimes administered by ESDC

and IRCC respectively.

Regulatory conditions include, but are not limited to, requiring employers to be actively engaged

in the business, provide the same wages, occupations and working conditions as set out in the job

offer, and make reasonable efforts to provide an abuse-free workplace. Of significance to this

paper’s discussion, employers are also required to comply with federal or provincial employment

and recruitment legislation. That could, for example, require compliance with a provincial

employer prohibition against hiring unlicensed recruiters, as applicable. Employers found non-

compliant with these conditions could then face consequences pursuant to the IRPR.

10

Subsection 91(2) of the IRPA only permits (a) a lawyer who is a member in good standing of a law society of a province or a

notary who is a member in good standing of the Chambre des notaires du Québec; (b) any other member in good standing of a

law society of a province or the Chambre des notaires du Québec, including a paralegal; or (c) a member in good standing of the

ICCRC to represent or advise a person for consideration in connection with a proceeding or application under the IRPA. A

contravention of this is a criminal offence pursuant to subsection 91(9).

13

Sub-national

Jurisdiction over regulating workplaces and businesses, except for a small number of industries

that fall under federal jurisdiction, rests with the provinces at the sub-national level.

11

Most

matters of employment (labour standards, occupational health and safety, etc.) and the business

of employment agencies and private labour recruiters are as such regulated by the province in

which those actors operate. This includes minimum employment and labour standards for most

workplaces in the country. Within this regulatory capacity, provinces can place obligations on

employers hiring migrant workers, or they can stipulate if an international labour recruiter or

employment agency is legally allowed to operate as a business, and if so, under which conditions.

In general, migrant workers are entitled to the same minimum labour standards as Canadian

workers and are not legally excluded on the basis of their immigration status. In some

jurisdictions however, employees (both domestic and foreign nationals) in certain sectors such as

agriculture and domestic work do not have the same rights as workers in other sectors, for

example the right to bargain collectively. Migrant workers tend to be more exposed to the

consequences of these exemptions to some extent given that they tend to be disproportionately

employed in these sectors.

A comprehensive review of the full range of employment and labour laws (e.g. employment

standards, occupational health and safety, labour relations, human rights, etc.) for all workers in

each jurisdiction in Canada is beyond the scope of this paper. This discussion rather focuses on

the relevant provincial legal provisions, either incorporated into existing labour or employment

standards statutes, or in stand-alone statutes, that are designed to explicitly address the unique

realities of the international labour recruitment and/or employment of migrant workers. As the

statutory regulation of migrant worker employers, labour recruiters, and/or employment agencies

varies widely across Canada, this paper serves to consolidate their content and differences.

Eight out of ten provinces in Canada have some relevant legislation that regulates the

employment and/or recruitment of migrant workers. Legislation involves a range of measures,

from prohibiting charging recruitment fees to workers to recruiter licensing or employer

registration requirements. Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the three

territories, Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut have no comparable statutory

approach and are consequently not discussed in this paper. The active provinces, relevant

legislation, and respective administrative bodies under review are captured in Table 1.

For the most part, the respective body overseeing the administration of these regimes is

employment or labour standards bodies, the same authority responsible for enforcing minimum

labour standards like minimum wage. The notable exception to this approach is in Alberta where

the Consumer Protection Act and its Employment Agency Business Licensing Regulation oversee

international employment agencies, effectively covering the recruitment process of migrant

workers into the province.

11

The labour rights and responsibilities of employees and employers of federally regulated businesses and industries fall under the

Canada Labour Code; examples of such industries include banking, transportation (marine, air, railway), telecommunications, and

radio and television.

14

Figure 2: Provinces with migrant worker employment and/or recruitment law

Figure 3: Timing of coming into force of relevant provincial regulation

15

Table 1: Provincial regulation of employment/recruitment of migrant workers

Province

Originating

legislation Associated regulations Administered by Timing

British

Columbia

(B.C.)

Temporary

Foreign Worker

Protection Act

(standalone)

Temporary Foreign

Worker Protection

Regulation B.C. Reg.

158/2019

Employment

Standards (Ministry of

Labour)

Assented to in 2018,

provisions staged into

force over 2019–2020

Alberta

(Alta.)

Consumer

Protection Act

Designation of Trades

and Businesses

Regulation; Employment

Agency Business

Licensing Regulation;

General Licensing and

Security Regulation

Consumer Programs

(Service Alberta)

Major relevant

amendments in 2012

(framework in place

since 1960s)

Saskatchewan

(Sask.)

Foreign Worker

Recruitment and

Immigration

Services Act

(standalone)

Foreign Worker

Recruitment and

Immigration Regulations

Employment

Standards (Ministry of

Labour Relations and

Workplace Safety)

Assented to and in

force in 2013

Manitoba

(Man.)

Worker

Recruitment and

Protection Act

(standalone)

Worker Recruitment and

Protection Regulation

Employment

Standards (Manitoba

Growth, Enterprise

and Trade)

Assented to in 2008,

in force 2009

Ontario

(Ont.)

Employment

Protection for

Foreign Nationals

Act (standalone)

Ontario Regulation

348/15; Ontario

Regulation 47/10

Employment

Standards (Ministry of

Labour)

Initial Act (live-in

caregivers) in force

2010; significant

amendments and

expanded coverage in

2015

Quebec

(Que.)

Act respecting

Labour Standards

Regulation respecting

personnel placement

agencies and recruitment

agencies for temporary

foreign workers

Commission des

normes, de l’équité,

de la santé et de la

sécurité du travail

(CNESST)

Foreign worker

provisions assented to

in 2019, in force in

2020

New

Brunswick

(N.B.)

Employment

Standards Act

General Regulation 85-

179

Employment

Standards

(Department of Post-

Secondary Education,

Training and Labour)

Relevant foreign

worker legislation

assented to and in

force in 2014

Nova Scotia

(N.S.)

Labour Standards

Code

General Labour

Standards Code

Regulations

Labour Standards

(Department of

Labour and Advanced

Education)

Relevant foreign

worker legislation

assented to in 2011,

in force 2013

International normative framework

In order to frame the comparative discussion on provincial statues regulating the recruitment and

employment of migrant workers, select international principles are used as a comparative

thematic framework. This section provides an overview of the international normative context on

fair and ethical labour recruitment, from which the paper’s framework is derived.

International human and labour rights norms that promote the protection of migrant workers and

the fair governance of labour migration, including fair labour recruitment, are found in a number

of legally binding treaties and non-binding instruments.

16

Some relevant binding instruments include:

− United Nations International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant

Workers and Members of Their Families

12

,

− ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29) and its Protocol of 2014 to the Forced

Labour Convention, 1930 (P029)

13

,

− ILO Migration for Employment Convention, 1949 (No. 97)

14

,

− ILO Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions) Convention, 1975 (No. 143)

15

,

− ILO Private Employment Agencies Convention (No. 181)

16

, and

− ILO Domestic Workers Convention (No. 201)

17

.

Among these, Canada has only ratified the ILO Forced Labour Convention and its Protocol, the

latter entered into force on June 17, 2020. The Forced Labour Protocol requires ratifying States to

take appropriate steps to prevent forced labour, protect victims, and guarantee them access to

effective remedies and compensation. Article 2 of the Protocol includes the following measure to

be taken: “protecting persons, particularly migrant workers, from possible abusive and fraudulent

practices during the recruitment and placement process”.

In terms of relevant non-binding normative instruments, Canada voted in favour to adopt the

United Nations Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) in 2018.

Objective 6 of the GCM is to “facilitate fair and ethical recruitment and safeguard conditions that

ensure decent work” and includes action commitments to improve regulations on private

recruitment agencies to align with international guidelines, prohibit recruiters and employers

from charging recruitment fees or related costs to migrant workers, and establish mandatory,

enforceable mechanisms for effective regulation and monitoring of the recruitment industry (see

Appendix III for full text of objective).

Non-binding instruments published by the ILO include the Multilateral Framework on Labour

Migration (2006)

18

and the General Principles and Operational Guidelines for Fair Recruitment

(2016)

19

, much of which are derived from relevant international labour standards. Regarding the

latter, the General Principles are intended to orient implementation of fair recruitment at all

levels, while the Operational Guidelines address responsibilities of specific actors in the

recruitment process, namely governments, employers, and recruiters. Governments are addressed

in their regulatory capacity as having the “ultimate responsibility for advancing fair

recruitment…to reduce abuses practised against workers, both nationals and migrants, during

recruitment, gaps in laws and regulations should be closed, and their full enforcement pursued.”

12

UN, International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, adopted by

General Assembly resolution 45/158 of 18 December 1990.

13

Convention 29, Forced Labour Convention (1930), adopted Geneva, 14th ILC session (28 Jun 1930); Protocol 29, Protocol of

2014 to the Forced Labour Convention (2014), adopted Geneva 103rd ILC session (11 Jun 2014).

14

Convention 97, Migration for Employment Convention (Revised) (1949), adopted Geneva, 32nd ILC session (1 Jul 1949).

15

Convention 143, Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions) Convention (1975), adopted Geneva, 60th ILC session (24 Jun

1975).

16

Convention 181, Private Employment Agencies Convention (1997), adopted Geneva, 85th ILC session (19 Jun 1997).

17

Convention 189, Domestic Workers Convention (2011), adopted 100th ILC session (16 June 2011).

18

ILO Multilateral Framework on Labour Migration: Non-binding principles and guidelines for a rights-based approach to labour

migration (Geneva: ILO, 2006) adopted by the Tripartite Meeting of Experts on the ILO Multilateral Framework on Labour

Migration (Geneva, 31 October–2 November 2005).

19

ILO General Principles and Operational Guidelines for Fair Recruitment (Geneva: ILO, 2016) adopted by the Tripartite Meeting of

Experts on Fair Recruitment (Geneva, 5-7 September 2016).

17

COMPARATIVE DISCUSSION OF REGULATORY APPROACHES

With this normative context in mind, an adapted fair recruitment framework has been developed

based on the ILO’s General Principles and Operational Guidelines for Fair Recruitment to

structure the comparative discussion of provincial regulatory approaches to recruitment and/or

employment of migrant workers. Put simply, the remainder of this paper takes the provincial

statutory regimes listed in Table 1 and compares them using the following eight thematic

principles:

Fair recruitment thematic norms used in this paper:

(1) Laws that apply to all. Appropriate legislation and policies on employment and recruitment should

apply to all workers, labour recruiters and employers.

(2) No recruitment fees. No recruitment fees or related costs should be charged to, or otherwise be borne

by, workers or jobseekers.

(3) Licensing and registration. Regulation of employment and recruitment activities should be clear and

transparent and effectively enforced. The use of standardized registration, licensing or certification

systems should be highlighted.

(4) Freedom of movement. Freedom of workers to move within a country or to leave a country should be

respected. Workers’ identity documents and contracts should not be confiscated, destroyed or retained.

(5) Freedom from deception or coercion. Workers’ agreements to the terms and conditions of recruitment

and employment should be voluntary and free from deception or coercion.

(6) Access to information. Workers should have access to free, comprehensive and accurate information

regarding their rights and the conditions of their recruitment and employment.

(7) Access to grievance mechanisms. Workers, irrespective of their presence or legal status in a State,

should have access to free or affordable grievance and other dispute resolution mechanisms in cases of

alleged abuse of their rights in the recruitment process, and effective and appropriate remedies should be

provided where abuse has occurred.

(8) Effective enforcement: Governments should effectively enforce relevant laws and regulations, and

require all relevant actors in the recruitment process to operate in accordance with the law.

18

Figure 4: Fair recruitment principles

19

1. LAWS THAT APPLY TO ALL

Appropriate legislation and policies on employment and recruitment should apply to all workers,

labour recruiters and employers.

Key questions: Which actors involved in migrant worker recruitment are covered by relevant legislation?

How migrant workers are defined and are any groups excluded? Are certain employers or recruiters

exempt from obligations in law or policy?

This principle maintains that appropriate legislation and policies on employment and recruitment

should be universal in nature, that is, that rights and obligations should apply to all workers and

all businesses, recruiters and employers alike. Universal application involves legal obligations

and protections that cover everyone, without exception.

Given the restricted scope of the paper to only examine the statutes listed in Table 1, the

following section strictly explores the application of coverage for migrant workers, their

employers and recruiters in these statutes (i.e., not other existing employment standards law).

Perhaps most interestingly, each province in Canada differs in scope and coverage, largely rooted

in the way in which foundational definitions of migrant workers and their recruiters and

employers are drafted and interpreted. Legal exemptions and policy exceptions uniquely restrict

application of definitions and associated protections and obligations across jurisdictions.

To start, it is important to clarify that the provincial laws under review themselves do not all

apply to the same actors involved in the migrant worker employment and recruitment process

(e.g., employer, labour recruiter, employment agency, and immigration consultant). For most

statutes examined here, employers and labour recruiters of migrant workers are captured, while

in the case of New Brunswick’s Employment Standards Act, only the employers of migrant

workers have legal obligations. Alberta’s Consumer Protection Act and its Employment Agency

Business Licensing Regulation have relevant coverage for migrant worker recruitment through

oversight of international employment agencies but not employers. Saskatchewan uniquely

regulates employers, recruiters, and immigration consultants under its Foreign Worker

Recruitment and Immigration Services Act.

Table 2: To whom does the relevant legislation apply?

Select Provincial Law under Review Employer

Labour

Recruiter

Employment

Agency

Immigration

Consultant

British Columbia

Temporary Foreign Worker Protection Act

— —

Alberta

Employment Agency Business Licensing Regulation

— —

—

Saskatchewan

Foreign Worker Recruitment and Immigration Services Act

—

Manitoba

Worker Recruitment and Protection Act

— —

Ontario

Employment Protection for Foreign Nationals Act

— —

Quebec

Regulation respecting personnel placement agencies and

recruitment agencies for temporary foreign workers

— —

New Brunswick

Employment Standards Act

—

— —

Nova Scotia

Labour Standards Code

— —

20

Secondly, the way in which workers or migrant workers are defined in each legislation is also

important to articulate as it determines the scope and potential exceptionality of the rules applied

over their employers or recruiters. While generally the federal government (IRCC) understands

migrant worker populations to be those foreign nationals already in Canada and usually holding a

work permit or other work authorization (e.g., work permit exemption) under the TFWP or IMP,

the provinces also include “job seekers” in their scope. This simply ensures that prospective

migrant workers, not yet employed or authorized to work in Canada, are also captured given the

international nature of their labour recruitment and need for protection at the employment-

seeking stage of their migration.

Figure 5: Migrant worker population and provincial scope

Since Alberta’s relevant legislation includes both international and national employment

agencies, that is, it is broadly concerned with workers not limited to migrants, its definition is

accordingly the broadest with no exceptions in law or policy. Ontario, New Brunswick,

Saskatchewan and British Columbia consider any foreign national (i.e., not a Canadian citizen or

permanent resident in Canada) working or seeking employment in the respective province to be a

foreign worker for the purpose of their legislation. Similarly, Nova Scotia’s definition is a foreign

national who is recruited to become employed in Nova Scotia, regardless of whether the

individual becomes so employed. However in policy, three groups are excluded from Nova

Scotia’s definition, generally limiting scope. Finally, Manitoba and Quebec have relatively

narrow migrant worker definitions by prescribing exemptions in regulations, practically

excluding any migrant worker that comes to the respective province without an LMIA.

20

This

means that only migrant workers who come under the TFWP are covered by the respective

legislation in these jurisdictions.

20

Under the terms of article 22 of the Canada–Quebec Accord, Quebec’s consent is required to grant entry to migrant workers who

are subject to federal LMIA requirements, i.e., those who come under the TFWP. Migrant workers destined to Quebec must

obtain the consent of the Minister of the Ministère de l’Immigration, Francisation et Intégration to enter Quebec and take

temporary employment. This consent is granted through the issuance of a Quebec Acceptance Certificate (Certificat d’acceptation

du Québec) (CAQ). Migrant workers who work in Quebec under the IMP (exempt from the LMIA) do not require a CAQ.

21

Table 3: Which migrant workers are covered by relevant provincial legislation: how are they

defined?

Province and

relevant law

Term

used Definition Exclusions

Alberta

Employment Agency

Business Licensing

Regulation

Person Persons seeking employment or

information respecting employers

seeking employees (*no reference to

foreign nationals).

N/A

Ontario

Employment

Protection for Foreign

Nationals Act

Foreign

national

Every foreign national who, pursuant

to an immigration or foreign

temporary employee program, is

employed in Ontario or is attempting

to find employment in Ontario.

N/A

New Brunswick

Employment

Standards Act

Foreign

worker

A foreign national who is working or

seeking employment in the Province.

N/A

Saskatchewan

Foreign Worker

Recruitment and

Immigration Services

Act

Foreign

worker

A foreign national working in or

seeking employment in

Saskatchewan

N/A

British Columbia

Temporary Foreign

Worker Protection Act

Foreign

worker

A foreign national who is an

employee, as defined in the

Employment Standards Act, in British

Columbia or seeking employment in

British Columbia

N/A

Nova Scotia

Labour Standards

Code

Foreign

worker

A foreign national who is recruited to

become employed in the Province,

regardless of whether the individual

becomes so employed.

• International students

• Specialized service providers

• Independent contractors

Manitoba

Worker Recruitment

and Protection Act

and Regulation

Foreign

worker

A foreign national who, pursuant to

an immigration or foreign temporary

worker program, is recruited to

become employed in Manitoba

A foreign national authorized to work

under these IRPR provisions:

(a) section 186 (no permit required);

(b) section 204 (international

agreements);

(c) section 205 (Canadian interests);

(d) section 206 (no other means of

support);

(e) section 207 (applicants in Canada),

except clause 207(a);

(f) section 208 (humanitarian reasons)

Quebec

Regulation respecting

employment

placement agencies

and temporary foreign

worker recruitment

agencies

Temporary

foreign

worker

A foreign national who is staying or

wishes to stay temporarily in Québec

to carry out work with an employer

under the temporary foreign worker

program provided for in Division II of

Chapter II of the Québec Immigration

Regulation.

Foreign nationals exempt from the LMIA,

including open work permit holders and

work permit-exempt individuals

Note: “foreign national” means an individual who is not a Canadian citizen or permanent resident in all cases.

Thirdly, the way in which recruiters, employment agencies, and employers are defined and

exempted from key obligations is also worth noting. For example, if recruiters or agencies are

required to obtain a license to recruit migrant workers (as discussed in detail in section 3), but

exemptions apply to this requirement in law or policy, this accordingly restrains universal

coverage. These exemptions can be based on the nature of the employer’s business (e.g., hiring as

a government, educational institution) or recruiter identity (e.g., recruiting as an employer, family

22

member) or on the nature of job or stream under which the migrant worker is authorized to work

(e.g., type of work permit, skill level of job).

Table 4: Exemptions to employer registration requirements

Who is exempt from employer registration? B.C.* Sask. Man. Que. N.B. N.S.

Employer-based

Government/public entity

TBD

— — —

Foreign government (e.g., diplomatic post)

TBD

— — — —

Universities

TBD

— — — —

Worker/position-based

If hiring NOC 0 and A skill level jobs

TBD

— — — —

If hiring independent contractors and specialized service

providers

TBD

— — — —

If hiring open work permit holders

TBD

—

— —

If hiring work-permit exempt migrant workers

TBD

— —

If hiring international students (also work-permit exempt)

TBD

—

If hiring IMP (LMIA-exempt) work permit holders

TBD

**

—

—

Note: Employer registration is not required under Ontario’s EPFNA nor Alberta’s EABLR.

*

At time of writing, B.C. employer registration was not yet in force; details are To Be Determined (TBD).

** Employers hiring LMIA-exempt clergy and occupations under international agreements like NAFTA are not exempt.

Exempt

de facto exemption applies as migrant workers in the category are excluded from respective migrant worker definition and related

legislation (i.e., employers would not be required to register when hiring these excluded categories).

Table 5: Exemptions to recruiter licensing requirements

Who is exempt from recruiter licensing? B.C. Alta. Sask. Man. Que. N.S.

Employer-based

Employer and employee working on their behalf

— —

Family member

—

— —

Government/public entities

Educational institution

— —

Worker/position-based

If recruiting NOC 0 or A position — — — — —

If recruiting high wage position — — —

*

— —

If recruiting IMP (LMIA-exempt) work permit holders — — —

—

If recruiting work permit-exempt migrant workers — — —

—

If recruiting international students for work — — —

—

If recruiting on behalf of a union —

— — —

If recruiting athletes or performing artists —

—

— — —

If recruiting specialized service providers or independent

contractors

—

— — — —

Note: Recruiter licensing is not required under Ontario’s EPFNA nor New Brunswick’s ESA.

* Only exempt if respective employer has received written authorized to use unlicensed recruiter and the wage is twice the Manitoba

average wage.

Exempt

de facto exemption applies as migrant workers in the category are excluded from respective migrant worker definition and related

legislation (i.e., recruiters would not be required to license when recruiting these excluded categories).

23

PROVINCIAL OVERVIEW

Each provincial statutory framework is briefly discussed below, roughly starting with provinces

with the broadest application/coverage of their migrant worker provisions to relatively more

limited application, taken together. Specific obligations and protections are referenced at a high

level here given that the subsequent sections explore these elements in further detail.

Alberta – Employment Agency Business Licensing Regulation

Alberta’s legislation that addresses international labour recruitment is uniquely under the Consumer

Protection Act (formerly called the Fair Trading Act) and its Designation of Trades and Businesses

Regulation and Employment Agency Business Licensing Regulation (EABLR).

21

Combined, these

instruments establish rules for employment agencies operating in Alberta, including any business

trying to find people for work, find work for people, or evaluating or testing an individual for skills

or knowledge required for work. Licensing is required and legal obligations are imposed, including

the requirement to enter into agreements with job seekers and employers. The EABLR also

prohibits employment agencies from engaging in unfair practices towards both parties.

This is the only jurisdiction reviewed that does not enforce international labour recruitment

regulations by a labour or employment standards body but rather by the consumer protection body

(Service Alberta). Accordingly, this set of legislation does not have direct obligations over

employers of migrant worker employees.

22

Alberta’s EABLR is reviewed here because it

uniquely requires licensing of both national and international employment agencies.

23

The

recruitment of migrant workers falls into the latter, as the distinction between national and

international is based on where the job seekers are sourced for work. The EABLR was also

amended significantly in 2012 in response to a significant increase in migrant workers recruited to

Alberta and the range of associated labour recruitment issues that were consequently addressed.

Under the Designation of Trades and Business Regulation, employment agency business does not

include the following list of activities, and thus employment agencies engaging in these activities

do not require a licence under the EABLR:

− activities of a school with respect to employment for students or graduates (private

vocational training, public post-secondary, publicly funded private post-secondary);

− activities of an organization funded by government;

− activities of an employer with respect to employment of employees;

− activities of an industry association, if minister designates and no fee, reward or other

compensation is charged to employees;

− activities of a board or commission established under the Marketing of Agricultural

Products Act;

− operation of a trade union; or

− securing employment for athletes or performing artists in their respective area of expertise.

21

Consumer Protection Act, RSA 2000, c C-26.3; Designation of Trades and Businesses Regulation, Alta. Reg. 178/1999;

Employment Agency Business Licensing Regulation, Alta. Reg. 45/2012.

22

Employers in Alberta, including those who employ migrant workers, are otherwise covered by Alberta’s Employment Standards

(minimum wage, hours of work, overtime, rest periods, etc.); Occupational Health and Safety (workplace hazards, safety

requirements), Human Rights (discrimination under protection grounds) and Workers’ Compensation Board (workplace injuries).

The Government of Alberta also administers a Temporary Foreign Worker Advisory Office with locations in Edmonton and

Calgary to help migrant workers, international students with work authorization, and their employers understand their rights and

responsibilities, including finding solutions to situations involve unfair, unsafe or unhealthy working conditions.

23

Other provinces also regulate employment agencies but their respective legislation is excluded from comparative review in this

paper as they are not designed to explicitly address international labour recruitment (i.e., migrant workers), unlike EABLR.

24

Finally, as discussed above, Alberta is also the only province compared in this paper where no

specific definitions pertaining to “foreign nationals” or “migrant workers” apply. In this case,

migrant workers fall under the definition of a “person seeking employment” as an individual for

whom an employment agency secures or attempt to secure employment, or an individual who is

evaluated or tested for skills or knowledge required for employment by an employer, where an

employment agency carries out or arranged the evaluation or testing, and the individual or the

employment is in Alberta. As such, these definitions provide a relatively broad application of

obligations for recruiters and protections for migrant workers, regardless of their immigration

status or type of work authorization.

Ontario – Employment Protection for Foreign Nationals Act

In Ontario, the Employment Protection for Foreign Nationals Act (EPFNA) applies to all foreign

nationals who are employed or seeking employment in Ontario pursuant to an immigration or

foreign temporary employee program.

24

This application is a significant amendment to the initial

statute in Ontario which only applied to live-in caregivers (domestic workers).

25

As a result, one

of the relatively broadest interpretation and coverage of law applies in this province.

The EPFNA is enforced by the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development’s

Employment Standards division. Some of the key rights and obligations include prohibitions on

recruiters from charging any fees to migrant workers, generally preventing employers from

recovering costs from foreign nationals, prohibiting both employers and recruiters from taking a

migrant worker’s personal property, including their passport, and requiring recruiters (and in

some cases, employers) to distribute information to migrant workers on their rights under the

EPFNA and other relevant legislation.

With regard to application, the EPFNA applies to every foreign national who, pursuant to an

immigration or a foreign temporary employee program, is employed in Ontario or is attempting

to find employment in Ontario (migrant worker); every person who employs a foreign national in

Ontario pursuant to an immigration or foreign temporary employee program (employer); every

person who acts as a recruiter in connection with the employment of a foreign national in Ontario

pursuant to an immigration or foreign temporary employee program (recruiter); and every person

who acts on behalf of an employer or recruiter.

Generally, a migrant worker who has a work permit allowing them to work in Ontario is covered,

while work permit-exempt foreign nationals working pursuant to an immigration program are

assessed on a case-by-case basis. They are considered to be “attempting to find employment” if

the individual possesses a work permit, has made an application for a work permit, or if there is

evidence to demonstrate that the foreign national has communicated with a recruiter about

finding employment in Canada. Practically, this does not limit the application of the EPFNA to

any type of work permit holder (open or employer-specific, LMIA or LMIA-exempt, and so on)

nor does it require the foreign national to necessarily hold legal immigration status in the case of

one “attempting to find employment”. It could be interpreted to extend, for example, to study

permit holders (international students) who generally work in Canada without a work permit, or

work permit holders who are on track to permanent residence through a provincial nominee

program (PNP).

24

Employment Protection for Foreign Nationals Act (Live-in Caregivers and Others), 2009, SO 2009, c 32.

25

Bill 18, the Stronger Workplaces for Stronger Economy Act, 2014, amended the application of the Employment Protection for

Foreign Nationals Act (Live-in Caregivers and Others), 2009 significantly. Formerly, the Act only covered foreign nationals

employed as live-in caregivers. The amendments came into force on November 20, 2015.

25

With respect to the employer, in order for the EPFNA to apply, that employer must ultimately

employ a migrant worker, as defined above. In other words, the obligations of an employer apply

only with respect to migrant workers who are actually hired by the employer.

A person is considered to be acting as a recruiter if the person: finds, or attempts to find, an

individual for employment; finds or attempts to find employment for an individual; assists

another person in doing any of those things (described above); or refers an individual to another

person to do those things. Guidance suggest a degree of limited applicability if the recruiter is a

foreign government.

26

It is important to note that while this coverage is broad, Ontario does not require any licensing or

registration of its recruiters and employers respectively, as in some other jurisdictions (see

section 3). This may explain some of the restrictions that follow below in provinces that prescribe

such obligations.

Saskatchewan – Foreign Worker Recruitment and Immigration

Services Act

Migrant workers recruited outside of Saskatchewan are protected under the Foreign Worker

Recruitment and Immigration Services Act (FWRISA), a standalone statute, and its Foreign

Worker Recruitment and Immigration Services Regulations that together regulate recruitment and

immigration services provided by migrant worker recruiters, immigration consultants, and

immigration lawyers.

27

The Ministry of Labour Relations and Workplace Safety is responsible

for administering the FWRISA, including licensing of recruiters and consultants, registering

employers who are hiring foreign workers, and handling complaints related to these actors where

mistreatment under the FWRISA has occurred.

28

FWRISA defines a migrant worker broadly as a foreign national working in or seeking

employment in Saskatchewan, and they are called a “foreign worker”. A foreign worker recruiter

is a person who, for a fee or compensation, provides recruitment services. Recruitment services

are defined in the FWRISA as services that assist a foreign national or an employer to secure

employment for a foreign national in Saskatchewan, including:

− finding or attempting to find employment in Saskatchewan for a foreign national;

− assisting or advising an employer in the hiring of a foreign national;

− assisting or advising another person in doing the things mentioned above;

− referring a foreign national to another person who does the things mentioned above; and

− providing or procuring settlement services (services to assist a foreign national in adapting

to society/economy or obtaining access to social, economic, government or community

program, networks and services).

Recruiters are required to obtain a licence, except for employers, family members, governments,

educational institutions, and unions. Saskatchewan is the only province where immigration

consultants are also regulated under the same statute as recruiters (also required to obtain a

licence). Under the FWRISA, immigration consultants are defined as a person who, for a fee or

compensation, provides immigration services. Exemptions from immigration consultant licensing

26

Per the interpretation manual, the EPFNA, as provincial legislation, cannot generally be enforced against a foreign government

because of the application of the federal State Immunity Act.

27

The Foreign Worker Recruitment and Immigration Services Act, SS 2013, c F-18.1; The Foreign Worker Recruitment and

Immigration Services Regulations, RRS c F-18.1 Reg 1.

28

Prior to April 1, 2017, the FWRISA was administered by the provincial immigration ministry before being transferred to the

provincial ministry of labour.

26

apply to lawyers, non-fee charging family members, and persons who represent a person who is

the subject of Immigration and Refugee Board proceedings.

Employers of migrant workers must register if they directly or indirectly recruit a foreign

national, though relatively broader legal exemptions apply than the exemptions to recruiter

licensing. Employers do not have to register if they hire open work permit holders, work-permit

exempt foreign nationals, and some LMIA-exempt occupations except clergy and those under

international agreements such as NAFTA.

While the exemptions above apply to licensing and registration, it is important to note that

foreign worker recruiters, immigration consultants, and employers are equally prohibited from a

number of unfair practices (detailed in section 5), with no exemptions in place.

British Columbia – Temporary Foreign Worker Protection Act

In British Columbia, the standalone Temporary Foreign Worker Protection Act (TFWPA) and

Regulation constitute the regulatory approach to license migrant worker recruiters, register

employers, and protect migrant workers in the province.

29

In addition to licensing and registration,

the TFWPA prescribes a number of prohibited practices to improve protection for migrant workers.

Migrant workers are captured by the definition of “foreign worker” in the TFWPA as a foreign

national who is an employee, as defined in the Employment Standards Act, or seeking

employment in British Columbia. A “foreign worker recruiter” is a person who, for a fee or

compensation, received directly or indirectly, provides recruitment services. Recruitment services

are services that assist a foreign national to secure employment in British Columbia or assist an

employer to secure employment in British Columbia for a foreign national, including:

− finding or attempting to find employment in British Columbia for a foreign national,

− assisting or advising an employer in the hiring of a foreign national,

− assisting or advising another person in taking the actions described above, or

− referring a foreign national to another person who takes the actions above.

Exemptions to the requirement to hold a licence as a recruiter apply to employers, family

members, educational institutions, and governments. At the time of writing, employer obligations

to register are not yet in force, and if exemptions apply, they would be prescribed in regulation.

With respect to prohibited practices in place to protect workers (discussed further in section 5),

all recruiters and employers are equally prohibited with no exemptions in place.

Nova Scotia – Labour Standards Code

In Nova Scotia, protective measures specific to migrant workers are provided for in the Labour

Standards Code (LSC).

30

These include rules regarding charging and recovering recruitment fees

or costs from a worker, holding a migrant worker’s property, and requirements on migrant

worker employers and recruiters to proactively register and license, respectively.

The LSC defines a migrant worker as a foreign national who is recruited to become employed in

Nova Scotia, regardless of whether the individual becomes so employed, and they are called a

“foreign worker”. In policy, exceptions to this definition apply: international students (working in

co-op placements, internships/on or off campus and hold a valid study permit), specialized

29

Temporary Foreign Worker Protection Act [SBC 2018] c 45.

30

Labour Standards Code, RSNS 1989, c 246.

27

service providers (employed by a foreign business to provide a specialized service over a short

period of time), and independent contractors. These groups are not considered “foreign workers”

and are not covered by the applicable protections or employer/recruiter obligations under the LSC

that are specific to foreign workers. However, it is worth noting that the key prohibition against

charging recruitment fees applies to any person, and thus includes any migrant worker beyond the

LSC’s definition and its policy exclusion.

“Recruitment” is defined as the following activities, whether or not they are provided for a fee:

− finding or attempting to find an individual for employment,

− finding or attempting to find employment for an individual,

− assisting another person in attempting to do the things described above, or

− referring an individual to another person to do any of the things described above.

Recruiters are required to be licensed before they can recruit migrant workers, with exemptions

prescribed in legislation and regulation. Exemptions include employers, family members,

governments, universities and if they recruit a migrant worker for a NOC 0 (Management) or A

(Professional) skill level position.

Foreign worker employers are defined as a person who proposes to employ a foreign worker.

They are required to obtain an employer registration certificate and engage only licensed

recruiters of foreign workers, unless they fall under a regulatory exemption as a government,

universities, or any employer who recruits a migrant worker in a NOC O or A skill level position.

The National Occupational Classification (NOC) system uses five skill levels to categorize jobs:

NOC 0: management jobs

NOC A: professional jobs that usually call for a degree from a university, such as: doctors, dentists,

architects

NOC B: technical jobs and skilled trades that usually call for a college diploma or training as an

apprentice, such as: chefs, plumbers, electricians

NOC C: intermediate jobs that usually call for high school and/or job-specific training, such as: industrial

butchers, long-haul truck drivers, food and beverage servers

NOC D: labour jobs that usually give on-the-job training, such as: fruit pickers cleaning staff, oil field

workers

New Brunswick – Employment Standards Act

In New Brunswick, migrant workers have the same rights and obligations under the Employment

Standards Act (ESA)

31

as all employees in Brunswick. However, employers have additional

obligations under the ESA with respect to hiring migrant workers. Migrant workers are defined

broadly and called a “foreign worker”: a person who is not a Canadian citizen or permanent

resident of Canada and who is working in or seeking employment in New Brunswick.

The most significant requirement in the ESA is for employers to register with Employment

Standards once they hire a migrant worker. There are also a number of prohibited employer

practices; employers cannot require migrant workers to use and pay an immigration consultant,

misrepresent employment opportunities, and recover ineligible recruitment costs from migrant

workers, among other things. The only exemption from employer registration is applied to the

31

Employment Standards Act, SNB 1982, c E-7.2.

28

government sector, i.e., the Crown in the right of the Province, or any Crown corporation or

agency. However, no exemptions apply in the case of employer prohibitions.

Recruiters are not directly captured or regulated by the ESA. One might interpret the ESA,

however, to indirectly capture some recruiters, for example as those identified in some provisions

as a person who recruits foreign workers for employment on behalf of an employer.

Manitoba – Worker Recruitment and Protection Act

The Worker Recruitment and Protection Act (WRAPA) and its Regulations are standalone law

that increase protections for migrant workers and others in Manitoba and provide the criteria and

obligations that recruiters and employers must meet to be approved for a licence or registration,

respectively.

32

Under the WRAPA, a migrant worker, called a “foreign worker” is defined in

legislation as a foreign national, who pursuant to an immigration or temporary

foreign worker program, is recruited to become employed in Manitoba. Exemptions